Abstract

Introduction:

Substance use disorders (SUD) frequently co-occur with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Little is known, however, about how individuals with a single SUD diagnosis (relating to only one substance) compare to individuals with poly-SUD diagnoses (relating to more than one substance) on substance use and PTSD treatment outcomes. To address this gap in the literature, we utilized data from a larger study investigating a 12-week integrated, exposure-based treatment (i.e., Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and Substance Use Disorders using Prolonged Exposure, or COPE) to examine treatment outcomes by single vs. poly-SUD status.

Method:

Participants were 54 Veterans (92.6% male, average age = 39.72) categorized as having single SUD (n=39) or poly-SUD (n=15). T-tests characterized group differences in baseline demographics and presenting symptomatology. Multilevel models examined differences in treatment trajectories between participants with single vs. poly-SUD.

Results:

Groups did not differ on baseline frequency of substance use, PTSD symptoms, or treatment retention; however, individuals with poly-SUD evidenced greater reductions in percent days using substances than individuals with a single SUD, and individuals with a single SUD had greater reductions in PTSD symptoms than individuals with poly-SUD over the course of treatment.

Discussion:

The findings from this exploratory study suggest that Veterans with PTSD and co-occurring poly-SUD, as compared to a single-SUD, may experience greater improvement in substance use but less improvement in PTSD symptoms during integrated treatment. Future research should identify ways to enhance treatment outcomes for individuals with poly-SUD, and to better understand mechanisms of change for this population.

Keywords: Substance Use Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD, Prolonged Exposure, Polysubstance Use, Treatment Outcome

1. Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) frequently co-occur, such that individuals with PTSD are significantly more likely to develop SUD than individuals without PTSD (Debell et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2015). This psychiatric comorbidity is particularly prevalent among military Veterans (Petrakis et al., 2011; Teeters et al., 2017). For example, among Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) Veterans utilizing VA healthcare services, 63% of those diagnosed with SUD meet criteria for comorbid PTSD (Seal et al., 2011). Because the concomitance between SUD and PTSD contributes to an increased number of physical and mental health problems, as well as impairment in social and vocational functioning, it is imperative to identify factors that influence treatment outcomes (Anderson et al., 2017; Mills et al., 2006; Ouimette et al., 2006).

Polysubstance use is one factor that may influence treatment outcomes. Individuals with poly-substance use disorder (poly-SUD) who have been exposed to multiple traumas have a greater risk for medical health complications (e.g., HIV; Mills et al., 2006). Thus, individuals with poly-SUD may present to treatment with more severe symptomatology and have a more complicated course of treatment due to other comorbidities. The current study seeks to explore this theory by examining baseline clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in dually-diagnosed individuals with poly-SUD.

Several studies have explored whether the type of substance (e.g., alcohol, cocaine, opioids, cannabis) and/or the number of different substances used impacts PTSD symptomatology. Because different substances can be used to stimulate or depress the nervous system, an individuals’ substance of choice may be reflective of their PTSD symptomatology, as substances can be used to self-medicate PTSD symptoms (Khantzian, 1985). For example, a recent study by Dworkin and colleagues (Dworkin et al., 2018) investigated how specific and multiple substances were associated with the presentation of PTSD symptoms. They found that individuals with cannabis, cocaine, or opioid use disorders reported the most severe hyperarousal symptoms, and individuals with a sedative/hypnotic/anxiolytic use disorder reported the most severe numbing symptoms (Dworkin et al., 2018). Individuals with alcohol use disorder, or combined alcohol and drug use disorder, reported greater avoidance symptoms than those with any other substance use disorder (Dworkin et al., 2018). These findings highlight the heterogeneity of substance use and PTSD symptomatology among dually-diagnosed individuals. This may have important implications for treatment, such as informing what PTSD symptoms should be targeted based on specific substances or combinations of substances used. To date, however, no one has examined if individuals with poly-SUD report greater overall PTSD severity compared to individuals with single-SUD.

Only a few studies have examined how use of multiple substances impacts treatment outcomes and findings are mixed. Manhapra, Stefanovics, and Rosenheck (2015) found that among individuals admitted to an intensive PTSD program (N=22,948), those who used only alcohol or only marijuana at intake had lower rates of abstinence at 4-month follow-up, compared to individuals who used cocaine, opioids, and multiple substances. A meta-analyses of cognitive-behavioral interventions for SUD revealed that psychosocial interventions had less efficacy for poly-SUD populations compared to individuals with a single SUD (Dutra et al., 2008). Specifically, individuals with poly-SUD had the lowest percent days abstinence at post-treatment, compared to individuals with a single SUD (Dutra et al., 2008). It has yet to be examined how poly-SUD may be associated with PTSD treatment outcome. Further, previous research has relied on examining abstinence as an indication of substance use frequency, but did not utilize other measures of SUD treatment outcome (e.g., harm reduction).

Given the risks associated with poly-substance use and the considerable number of patients with PTSD/SUD who meet criteria for poly-SUD, it is critical to identify whether and how poly-SUD impacts treatment outcome when comorbid conditions are targeted. The aim of the current exploratory study is to investigate how individuals with PTSD and either single or poly-SUD compare at baseline and over the course of an exposure-based, integrated treatment designed to target both PTSD and SUD severity. It is hypothesized that individuals with poly-SUD would report a greater frequency of substance use and more severe PTSD symptomatology at baseline and throughout treatment as compared to individuals with a single SUD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were U.S. military Veterans enrolled in a larger randomized controlled trial (Back et al., 2019) examining the efficacy of a novel 12-week, exposure-based integrated treatment for comorbid PTSD and SUD (i.e., Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and Substance Use Disorders Using Prolonged Exposure, or COPE; Back et al., 2014) versus Relapse Prevention cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT; Carroll, 1998). This larger study lends evidence to the efficacy of COPE, demonstrating that COPE resulted in significantly greater reductions in PTSD than RP, as well as comparable reductions in SUD during treatment and greater reductions during follow up (Back et al., 2019). All participants met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; Amerian Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for current SUD and PTSD.

Only participants randomized to the COPE condition were included in the current analyses (N=54). Most participants were male (92.6%) with a mean age of 39.72 years (SD = 10.98). Participants primarily identified as Caucasian (68.5%) or African American (29.6%). Participants were recruited through the local Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, flyers posted in the community, and internet and newspaper advertisements. Inclusion criteria were: 1) Veteran, reservist, or member of the National Guard, 2) 18–65 years old, 3) meet DSM-IV criteria for SUD on the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Sheehan et al., 1997), 4) meet DSM-IV criteria for PTSD on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) with a total score ≥ 50. Exclusion criteria were: 1) current suicidality and/or homicidality with intent, 2) psychiatric or medical conditions requiring a higher level of care, 3) enrolled in current treatment for PTSD or SUD, and 4) severe cognitive impairment based on the Mini Mental Status Exam, with a cutoff score of 21 (Folstein et al., 1975). Participants who were stabilized on psychotropic medication for at least four weeks were permitted to participate.

2.2. Procedures

Following a baseline assessment to confirm eligibility, participants were randomized to receive 12 sessions of COPE (Back et al., 2014) or Relapse Prevention (Carroll, 1998). The COPE treatment integrates Prolonged Exposure (PE; Foa et al., 2007) for the treatment of PTSD with Relapse Prevention for SUD. Before each therapy session, participants completed measures assessing substance use and PTSD severity since the prior session. Abstinence was not required of participants, although it was strongly encouraged.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. SUD Diagnoses.

The MINI (Sheehan et al., 1997), a brief semi-structured interview, was used to assess diagnostic criteria for current alcohol and drug use disorders. Participants were categorized into the single-SUD group if they met current diagnostic criteria for only one type of substance. Participants were categorized into the poly-SUD group if they met current diagnostic criteria for more than one substance use disorder.

2.3.2. Substance Use Frequency.

The Timeline Followback (TLFB; Sobell and Sobell, 1992) is a calendar-based, self-report assessment of alcohol and drug use, which yields high test-retest reliability when compared with self and other reports of substance use (Carey, 1997). Substance use was assessed at baseline (60 days prior) and weekly during treatment. We examined likelihood of use (dichotomous variable: 0 = no use and 1= use) and percent days used (PDU), a continuous variable. The baseline assessment captured PDU over the 60 days prior to the baseline appointment and the weekly measures captured PDU since the previous appointment.

2.3.3. PTSD Diagnosis.

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., 1995) for DSM-IV-TR was used at baseline to assess diagnostic criteria for PTSD. The CAPS assesses the frequency and intensity of 17 DSM-IV-TR symptoms of PTSD. The CAPS is a well-validated measure and demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties, including good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability (Orsillo, 2002).

2.3.4. PTSD Severity.

The PTSD Checklist - Military Version (PCL-M; Weathers et al., 1994) is a continuous measure and was used in the current study to assess PTSD symptom severity at baseline and weekly during treatment. The PCL-M consists of 17 Likert-type scale items rated 1 (“Not at all”) through 5 (“Extremely”), and scores can range from 17 to 85. The PCL-M has good psychometric properties including good internal consistency, convergent validity, test-retest reliability, and temporal stability (Wilkins et al., 2011). In the current sample internal reliability at each assessment time point ranged from good to excellent (αs = 0.88 to 0.97).

2.4. Data Analysis

Group differences (i.e., single vs. poly-SUD) in demographic and baseline characteristics were assessed using chi-square or t-tests, as appropriate. Multilevel models in Mplus v 8.1 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2017) examined whether the two groups differed in SUD and PTSD severity, independently, across the course of treatment. Substance use was modeled using two-part modeling (Olsen and Schafer, 2001) to capture likelihood of use (0 = no use; 1= use) over the given week and frequency of use (PDU), conditioned on substance use. Intercepts in each of the models were allowed to vary. The first therapy session was coded as 0 and then session was entered as a fixed effect in the models. Substance use group (single SUD = −1; poly-SUD = 1) and the interaction of group by session were also specified as fixed effects. Prior to entering the SUD group as a predictor, it was examined whether a linear or quadratic effect of session number best fit the data. It was found that a linear model provided the best fit.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Most individuals in the sample (n=39) met criteria for a single SUD, and the remaining individuals (n=15) met criteria for poly-SUD. Of those in the poly-SUD group, only two participants met criteria for more than 2 SUDs (i.e., met criteria for 3 SUDs). As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants in the single SUD group and all of the participants in the poly-SUD group met criteria for an alcohol use disorder. Single SUD participants did not differ significantly from poly-SUD participants on demographic characteristics, including age (t(52) = −0.86, p = 0.39), sex (χ2 = 1.06, p = 0.30), and race (χ2 = 3.12, p = 0.21). Both groups reported exposure to a similar number of lifetime traumas (t(50) = 0.14, p = 0.89), baseline substance use frequency (t(20.13) = −0.37, p = 0.72), and PTSD severity, both according to the CAPS (t(52) = 1.49, p = 0.14) and the PCL-M (t(52) = 0.09, p = 0.93). Retention was also similar between groups (t(52) = 0.33, p = 0.74).

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Clinical Characteristics by SUD Group (N=54)

| Characteristic |

Single-SUD (n=39) |

Poly-SUD (n=15) |

|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or N | M(SD) or N | |

| Age | 38.92 (10.05) | 41.80 (13.26) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 37 | 13 |

| Female | 2 | 2 |

| Race | ||

| White/Caucasian | 29 | 8 |

| Black/African American | 9 | 7 |

| More than one/Other | 1 | 0 |

| Substance Use Diagnosis | ||

| Alcohol | 33 | 15 |

| Opioid | 4 | 5 |

| Cocaine | 1 | 7 |

| Marijuana | 1 | 4 |

| Sedative Hypnotic/Anxiolytic | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 0 | 1 |

| Baseline Substance Use Frequency (percent days using) | 45.68 (32.67) | 50.33 (44.35) |

| Baseline PTSD Severity (CAPS) | 79.64 (18.73) | 71.53 (15.46) |

| Baseline PTSD Severity (PCL-M) | 61.97 (11.47) | 61.67 (10.55) |

| Average Number of Lifetime Traumatic Events | 10.71 (2.92) | 10.57 (3.59) |

| Number of Treatment Sessions Completed | 8.95 (4.07) | 8.53 (4.37) |

Note. SUD = substance use disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; PCL-M = PTSD Checklist – Military Version.

3.2. Substance Use Frequency over the Course of Treatment

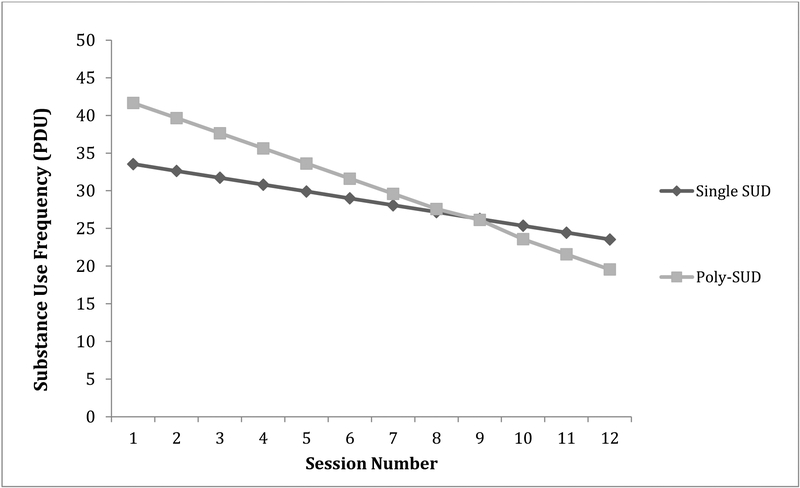

The number of participants using substances and means of PDU of any substance are provided in Table 2 by SUD group (single vs. poly-SUD) and treatment session. By end of treatment (Session 12), 45.5% of single-SUD participants and 75% of poly-SUD participants reported that they had abstained since the week prior. Among those who were using, single-SUD persons were using 25% of the time, compared to the poly-SUD group who was using 8% of the time. Results of the two-part model suggest that session number significantly predicted likelihood of use and PDU, such that participants in both groups had a lower likelihood and frequency of substance use as therapy progressed (see Table 3). That is, the number of single-SUD individuals and poly-SUD individuals using substances decreased and substance use frequency for both groups decreased as participants advanced through the treatment. SUD group did not predict probability of substance use or PDU but the interaction of session by SUD group predicted PDU, suggesting that individuals with poly-SUD evidenced greater reductions in substance use frequency over the course of treatment than individuals with a single SUD (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Number of individuals who used substances with means and standard deviations of substance use frequency and PTSD severity across treatment sessions by SUD group

| Single SUD | Poly-SUD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session # | Participants Who Used Any Substance (%) | Substance Use Frequency (Percent DaysUsed) | PTSD Severity (PCL-M) | Participants Who Used Any Substance (%) | Substance Use Frequency (Percent Days Used) | PTSD Severity (PCL-M) |

| 1 | 67.6 | 33.21 (36.91) | 58.28 (13.11) | 57.1 | 43.72 (42.72) | 58.14 (7.38) |

| 2 | 66.7 | 34.20 (36.88) | 57.92 (14.14) | 53.8 | 34.61 (40.35) | 59.23 (11.74) |

| 3 | 62.9 | 30.85 (34.61) | 54.09 (13.73) | 41.7 | 28.62 (40.03) | 53.17 (9.19) |

| 4 | 66.7 | 30.60 (30.91) | 51.03 (14.90) | 50.0 | 37.26 (39.82) | 57.08 (14.39) |

| 5 | 51.6 | 23.44 (31.92) | 48.16 (16.19) | 53.8 | 34.32 (40.41) | 57.31 (12.61) |

| 6 | 58.1 | 22.08 (26.44) | 41.70 (14.71) | 70.0 | 16.22 (26.28) | 56.73 (13.48) |

| 7 | 58.6 | 22.21 (26.14) | 41.11 (18.22) | 55.6 | 21.47 (28.64) | 52.33 (18.28) |

| 8 | 60.7 | 24.69 (31.92) | 39.00 (16.16) | 25.0 | 14.75 (29.14) | 51.75 (14.06) |

| 9 | 51.9 | 24.85 (29.97) | 37.73 (17.19) | 37.5 | 13.97 (22.15) | 51.89 (13.98) |

| 10 | 54.2 | 19.73 (25.05) | 35.61 (17.87) | 28.6 | 18.08 (25.51) | 52.57 (12.97) |

| 11 | 50.0 | 16.70 (23.56) | 37.24 (18.61) | 28.6 | 7.66 (12.14) | 46.88 (13.87) |

| 12 | 54.5 | 25.48 (31.00) | 33.86 (16.37) | 25.0 | 7.94 (16.15) | 44.89 (15.87) |

Note: Percentages calculated with participants with missing data excluded. SUD = substance use disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PCL-M = PTSD Checklist – Military Version.

Table 3.

Fixed Effects of Treatment Session and SUD Group as Predictors of Substance Use and PTSD Severity

| Estimate | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substance Use | Continuous | Categorical | ||||

| Intercept/Threshold | 37.61 | 5.00 | <0.001 | −2.19 | 1.15 | 0.057 |

| Session | −1.46 | 0.25 | <0.001 | −0.24 | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| SUD Group | 4.06 | 5.00 | 0.417 | −0.5 | 1.06 | 0.64 |

| Session x SUD Group | −0.55 | 0.25 | 0.029 | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.789 |

| PTSD Severity | B | SE | p | |||

| Intercept/Threshold | 58.55 | 2.10 | <0.001 | |||

| Session | −1.62 | 0.14 | <0.001 | |||

| SUD Group | 0.37 | 2.10 | 0.86 | |||

| Session x SUD Group | 0.58 | 0.14 | <0.001 | |||

Note: SUD = substance use disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; PCL-M = PTSD Checklist – Military Version;

p < 0.05.

Figure 1.

Estimated Change in Substance Use Frequency from First Treatment Session to End of Treatment by SUD Group

Note: SUD = Substance use disorder; PDU = Percent days used.

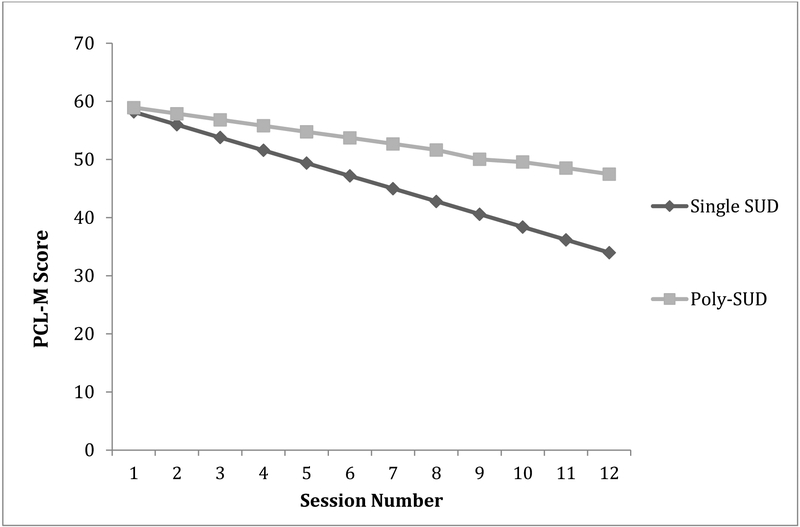

3.3. PTSD Severity over the Course of Treatment

Average PTSD severity by treatment session and SUD group is also presented in Table 2. Figure 2 illustrates the findings from the multilevel model, demonstrating that PTSD severity decreased significantly over the course of treatment for single and poly-SUD groups. Session and the interaction of session by SUD group significantly predicted PTSD severity (see Table 3), such that individuals with a single SUD evidenced significantly greater reductions in PTSD severity as compared to individuals with poly SUD.1

Figure 2.

Estimated Change in PTSD Severity from First Treatment Session to End of Treatment by SUD Group

Note: SUD = Substance use disorder; PCL-M = PTSD Checklist – Military Version.

4. Discussion

The frequent co-occurrence of SUD and PTSD among both civilians and military veterans is well-documented (Grant et al., 2015; Teeters et al., 2017). Although research has identified differences in treatment outcomes for single-SUD and poly-SUD individuals in SUD treatment (Dutra et al., 2008; Dworkin et al., 2018; Mills et al., 2006), no research to date has examined the effect of single versus poly-SUD among individuals with comorbid SUD/PTSD receiving integrated treatment. The current exploratory study sought to address this gap in the literature by examining presenting characteristics and response to integrated treatment among veterans with PTSD and single or poly-SUD who participated in an integrated, exposure-based treatment (i.e., COPE).

The results from the current study suggest that individuals with poly-SUD did not differ from individuals with single SUD with regard to baseline substance use frequency. By Session 12, the poly-SUD group was using substances approximately 8% of the time and the single SUD group was using approximately 25% of the time (see Table 2). Results of the multilevel model demonstrate that individuals in both groups showed significant reductions in substance use frequency across the course of treatment. Further, individuals with poly-SUD showed greater reductions than individuals with a single SUD. This finding may have been due to a relatively small sample of poly-SUD individuals and stands in contrast to previous research examining SUD-only populations, which reports worse treatment outcomes for poly-SUD individuals (i.e., lowest post-treatment abstinence, Dutra et al., 2008). The current study’s findings may be discrepant from Dutra et al.’s (2008) findings because abstinence was not used as the measure of SUD treatment outcome. Rather, we examined PDU as a measure of SUD treatment outcome because abstinence was encouraged but not required for participants. Trials that require a goal of abstinence may incur greater dropout or retain individuals with more severe SUD than the current study saw. Further, our findings may differ from Dutra and colleagues’ (2008) meta-analysis because they focused primarily on illicit substances. In the current sample, the majority of single-SUD participants had alcohol use disorder and most of the poly-SUD participants had an alcohol use disorder as well as a drug use disorder. Future research should examine the effect of single vs. poly-SUD on treatment outcomes among dually-diagnosed individuals with primarily drug use disorders.

Individuals in the poly-SUD group may have adhered to the SUD treatment component of COPE to a greater extent than the single SUD group, thereby demonstrating a greater reduction in substance use. Many individuals with co-occurring SUD and PTSD use alcohol or other substances to self-medicate the discomfort associated with PTSD symptoms (Khantzian, 1985; Leeies et al., 2010; Ouimette et al., 2010). Previous research with similar samples has demonstrated that reduction in SUD is largely attributable to PTSD symptom change (Badour et al., 2017). Thus, it is possible that because the COPE treatment targets PTSD symptoms concurrently with SUD, and is not specific to a particular substance, participants showed reductions in substance use frequency, particularly if they were diagnosed with multiple SUDs. Motivations for change may have also differed between groups, with the poly-SUD group identifying their behaviors as more risky or dangerous and therefore exhibiting higher motivations to reduce their substance use. Future research should address such group differences as they may prove to be predictors or influencers of treatment outcomes.

Individuals with poly-SUD reported similar levels of PTSD severity as individuals with single SUD at baseline. There were group differences in PTSD symptom severity over the course of treatment, though in the opposite direction of what was found for substance use. That is, individuals with a single SUD showed greater reductions of PTSD severity than individuals with poly-SUD across the course of treatment. Future research is needed to identify mechanisms to help explain why individuals with poly-SUD, despite having comparable reductions in substance use frequency, showed less improvement in PTSD treatment outcomes and how this relates to their substance use frequency. Because individuals in the poly-SUD group demonstrated more prominent reductions in substance use frequency, their PTSD symptoms may be more severe than the single-SUD group because they are no longer self-medicating their PTSD symptoms (Khantzian, 1985). Alternatively, individuals reducing use of multiple substances may be encountering more withdrawal symptoms, relative to individuals with single SUD, which may mimic or exacerbate PTSD symptoms. It may also be that individuals with poly-SUD may be less able to benefit from prolonged exposures perhaps due to a history of chronic use and/or greater neurocognitive impairment (Loeber et al., 2009). As many SUD/PTSD patients have polysubstance use (Mills et al., 2012), it will be important to develop, further adapt, or perhaps lengthen treatment in order to effectively reduce PTSD severity among patients with poly-SUD (Dutra et al., 2008).

The current exploratory study is limited by the relatively small, predominately male, veteran sample. Thus, it is uncertain how the findings might generalize to a more diverse population. The SUD groups were of unequal sizes and had little diversity in the substances being used, which may have impacted the results. We found that when we re-analyzed the data to include only individuals with alcohol use disorder or alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder, the effect of group by session on substance use frequency was no longer significant. It is possible that single SUD individuals with a drug use disorder were driving the effects found for substance use frequency in our main analyses. However, given the sample size, future research should aim to replicate these preliminary findings in larger samples. Further, the sample size was too small to examine the quantity of each substance separately and we did not collect data on whether poly-SUD individuals were using substances in combination or at different times on days in which they used both substances. This information will be important for future studies to collect so that the needs of poly-SUD individuals can be better characterized.

The current study consists of post-hoc analyses; thus caution is advised when considering any causal inferences that might be drawn from the results of this study. In addition, the current study examined self-report measures, which are subject to recall bias. Further, we were unable to examine substance use quantity at a granular level because there is no accurate way to standardize amount of use across substances. Future research should report biological markers of substance use. Additionally, the definition of “polysubstance” is defined ambiguously throughout the literature and not included in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some researchers define polysubstance use as using three or more substances within the same time period (e.g., Manhapra et al., 2015), whereas others define the term based on the number of SUD diagnoses a person is ascribed (e.g., Dutra et al., 2008). The outcomes may differ depending on how polysubstance use is defined and the findings should be interpreted with consideration to a given study’s definition.

In summary, PTSD patients with both single and poly-SUD evidenced significant reductions in SUD and PTSD severity during the course of an integrated, exposure-based treatment for PTSD/SUD. However, poly-SUD individuals had a greater reduction of substance use frequency and single SUD individuals had a greater reduction in PTSD severity over the course of treatment. The findings contribute to a growing literature on factors that influence treatment efficacy for integrated, exposure-based interventions. In particular, future research should focus on identifying ways to enhance PTSD treatment outcomes for individuals with poly-SUD. This may include incorporating extended treatment protocols for polysubstance users who are more likely to develop serious medical problems associated with drug use or experience re-traumatization (Mills et al., 2006). Future research may focus on developing an integrated treatment for polysubstance users that includes additional sessions targeting PTSD coupled with adjunct medication for SUD and PTSD symptoms.

Highlights.

Differences may exist between poly-substance and single-substance users with PTSD

Examined outcomes related to an integrated, exposure-based treatment

Poly-substance users had greater reductions in substance use frequency

Single substance users had greater reductions in PTSD symptom severity

Findings have implications for developing integrated treatments

Role of Funding Sources

This manuscript is the result of work supported, in part, by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (T32AA747430 and K23AA023845), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA030143 and K02DA039229). NIAAA and NIDA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

As all poly-SUD participants, but not all single SUD participants, met criteria for alcohol use disorder, we re-ran models limiting the sample to only poly-SUD participants and single SUD participants who met criteria for alcohol use disorder. This allows us to examine if single SUD individuals with only a drug use disorder drive the effects found in the models. Results from our re-analysis were relatively consistent with the model including the entire sample except that the effect of SUD group by session on substance use trended toward significance (p = 0.097).

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA), 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders, fifth ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RE, Bonar EE, Walton MA, Goldstick JE, Rauch SAM, Epstein-Ngo QM, Chermack ST, 2017. A latent profile analysis of aggression and victimization across relationship types among veterans who use substances. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 78, 597–607. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2017.78.597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Killeen T, Badour CL, Flanagan JC, Allan NP, Ana ES, Lozano B, Korte KJ, Foa EB, Brady KT, 2019. Concurrent treatment of substance use disorders and PTSD using prolonged exposure: A randomized clinical trial in military veterans. Addict. Behav 90, 369–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back SE, Foa EB, Killeen TK, Mills KL, Teesson M, Dansky Cotton B, Carroll KM, Brady KT, 2014. Concurrent Treatment of PTSD and Substance Use Disorders Using Prolonged Exposure (COPE): Therapist guide Treatments that work. US: Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Badour CL, Flanagan JC, Gros DF, Killeen T, Pericot-Valverde I, Korte KJ, Allan NP, Back SE, 2017. Habituation of distress and craving during treatment as predictors of change in PTSD symptoms and substance use severity. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 85, 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM, 1995. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. J. Trauma. Stress 8, 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, 1997. Reliability and validity of the time-line follow-back interview among psychiatric outpatients: A preliminary report. Psychol. Addict. Behav 11, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, 1998. Treating drug dependence: Recent advances and old truths, in Miller WR, Heather N (Eds.), Applied clinical psychology. Treating addictive behaviors. US: Plenum Press, New York, pp. 217–229. [Google Scholar]

- Debell F, Fear NT, Head M, Batt-Rawden S, Greenberg N, Wessely S, Goodwin L, 2014. A systematic review of the comorbidity between PTSD and alcohol misuse. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol 49, 1401–1425. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0855-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW, 2008. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin ER, Wanklyn S, Stasiewicz PR, Coffey SF, 2018. PTSD symptom presentation among people with alcohol and drug use disorders: Comparisons by substance of abuse. Addict. Behav 76, 188–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Hembree E, Rothbaum B, 2007. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Oxford University, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR, 1975. “Mini-Mental State”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res 12, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, Zhang H, Pickering RP, Ruan WJ, Smith SM, Huang B, Hasin DS, 2015. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72, 757–766. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ, 1985. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry 142, 1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeies M, Pagura J, Sareen J, Bolton JM, 2010. The use of alcohol and drugs to self-medicate symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression Anxiety 27, 731–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber S, Vollstadt-Klein S, von der Goltz C, Flor H, Mann K, Kiefer F, 2009. Attentional bias in alcohol-dependent patients: The role of chronicity and executive functioning. Addict. Biol 14, 194–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhapra A, Stefanovics E, Rosenheck R, 2015. Treatment outcomes for veterans with PTSD and substance use: Impact of specific substances and achievement of abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 156, 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Back SE, Brady KT, Baker AL, Hopwood S, Sannibale C, Barrett EL, Merz S, Rosenfeld J, Ewer PL, 2012. Integrated exposure-based therapy for co-occurring posttraumatic stress disorder and substance dependence: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 308, 690–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Peters L, 2006. Trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders: Findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Am. J. Psychiatry 163, 652–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 1998–2017. Mplus User’s Guide, eigth ed. Muthén and Muthén, California. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen MK, Schafer JL, 2001. A two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous longitudinal data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc 96, 730–745. doi: 10.1198/016214501753168389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orsillo SM, 2002. Measures for acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, in: Antony MM, Orsillo SM, Roemer L (Eds.), Practitioner’s Guide to Empirically Based Measures of Anxiety. AABT Clinical Assessment Series. Springer, Massachuettes, pp. 255–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Goodwin E, Brown PJ, 2006. Health and well being of substance use disorder patients with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Addict. Behav 31, 1415–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Read JP, Wade M, Tirone V, 2010. Modeling associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and substance use. Addict. Behav 35, 64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrakis IL, Rosenheck R, Desai R, 2011. Substance use comorbidity among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychiatric illness. Am. J. Addict 20, 185–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin ME, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG, 1995. Understanding comorbidity between PTSD and substance use disorders: two preliminary investigations. Addict. Behav 20, 643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, Cohen BE, Maguen S, Ren L, 2011. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001–2010: Implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 116, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Schinka J, Knapp E, Sheehan MF, Dunbar GC, 1997. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur. Psychiatry 12, 232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, 1992. Timeline Follow-Back, in: Litten RZ, Allen JP (Eds.), Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Humana Press, New Jersey, pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Teeters JB, Lancaster CL, Brown DG, Back SE, 2017. Substance use disorders in military veterans: Prevalence and treatment challenges. Subst. Abuse Rehabil 8, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, Keane T, 1994. PTSD checklist - Military version for DSM-IV. Available at https://deploymentpsych.org/system/files/member_resource/4-PCL-M.pdf (Accessed April 4, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins KC, Lang AJ, Norman SB, 2011. Synthesis of the psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL) military, civilian, and specific versions. Depression Anxiety 28, 596–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]