Abstract

Background Context:

Lumbar radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is an intervention used to treat facet-mediated chronic low back pain. In some studies with methods consistent with clinical practice guidelines, RFA results in improvements in pain and functional limitations. However, in other studies, RFA demonstrates limited benefit. Despite unanswered questions regarding efficacy of RFA, its use is widespread.

Purpose:

To describe trends in the utilization and cost of lumbar RFA and lumbar facet injections.

Study Design/ Setting:

Retrospective cohort study.

Patient Sample:

The sample was derived from the IBM/Watson MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases from 2007 – 2016.

Outcome Measures:

Longitudinal trends in the distribution and quantity of lumbar facet injections before lumbar RFA, corticosteroid administration during lumbar facet injections, progression to lumbar RFA after lumbar facet injections, lumbar RFA utilization, and costs of these interventions.

Methods:

Two primary cohorts were identified from patients who received lumbar RFA or lumbar facet injection procedures. Utilization rates per 100,000 enrollees were determined for both cohorts. The mean, median, and interquartile ranges of the number of facets targeted and costs per procedure were calculated by year and laterality, as well as overall. Costs in 2018 dollars were estimated by summing gross payment totals from patients and insurance plans. This study was supported by funds from the NIH, and has no conflict of interest associated biases.

Results:

From 2007 – 2016, lumbar RFA sessions performed per 100,000 enrollees per year increased from 49 to 113, a 130.6% overall increase (9.7% annually). Lumbar facet injection use increased from 201 to 251 sessions per 100,000 enrollees, a 24.9% overall increase (2.5% annually). In the year after a lumbar facet injection, 26.7% of patients received lumbar RFA; 28.6% received another injection but not RFA; and 44.7% received neither. The number of patients receiving two lumbar facet injection procedures prior to lumbar RFA grew from 51.1% in 2010 to 58.8% in 2016. For lumbar RFA, the cost per 100,000 enrollees went from $94,570 in 2007 to $266,680 in 2016, a 12.2% annual increase. For lumbar facet injections, the cost per 100,000 enrollees went from $257,280 in 2007 to $396,580 in 2016, a 4.9% annual increase.

Conclusions:

This analysis showed consistent growth in both the frequency and procedure cost of lumbar RFA and facet injections among a large, national, commercially insured population from 2007 to 2016.

Keywords: Zygapophyseal Joint, Radiofrequency Ablation, Injections, Procedures and Techniques Utilization, Database, Costs and Cost Analysis

Introduction:

Low back pain (LBP) is the primary condition contributing to disability in the United States (US), with annual costs of treatment exceeding $100 billion dollars.1–4 Lumbar facet joint pathology is believed to be the source of LBP for at least 15% of all adult patients and for up to 90% of older adults with LBP.5–8 Because painful facet joints cannot be accurately identified by clinical assessment or imaging studies, they are commonly identified in clinical practice by diagnostic local anesthetic blocks, such as medial branch nerve blocks (MBBs).9–13

Lumbar radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a commonly used minimally invasive intervention that selectively creates thermal lesions to the nerves supplying painful joints identified by MBBs.14–19 In some studies, particularly those that use stringent patient selection and RFA procedure techniques consistent with clinical practice guidelines, RFA results in large-magnitude, durable improvements in pain and functional limitations.20–26 However, other studies, some of which use alternative protocols for patient selection and RFA technique, demonstrate limited benefit of RFA.26–30 Furthermore, costs for RFA can be substantial, embroiling the procedure in controversy.31–33

Despite unanswered questions regarding efficacy of RFA in current practice, which may or may not be guideline-concordant, RFA use is widespread.19 For example, this procedure grew in the Medicare patient population by 568% from 2000 to 2014.19 To characterize RFA use in the United States‟ commercially insured population, the current study aimed to describe demographic characteristics of patients who received RFA, the number of lumbar facet injection procedures patients received before RFA, corticosteroid administration during facet injections, trends in the progression to lumbar RFA after lumbar facet injections, RFA utilization and growth, and the longitudinal costs of these interventions using insurance claims data provided by the IBM/Watson MarketScan Database from 2007 – 2016.34

Material and Methods:

Data Source:

This study was exempt from review by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board. Deidentified data were collected from the IBM/Watson (formerly Truven Health Analytics) MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases from 2007 – 2016. These databases include inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy claims for patients covered by employer-sponsored commercial insurance plans from over 150 employers across the US. Data pertaining to procedures and encounters, as well as financial expenditures by both patients and their insurance plans, are collected.34

Using these databases, two primary cohorts were identified from all patients enrolled between 2007 and 2016: The lumbar RFA cohort included all patients with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for lumbar RFA (CPT 64622, 64623, 64635, and 64636), and the lumbar facet injection cohort included all patients with CPT codes for lumbar facet injections, which includes lumbar MBBs and intra-articular facet joint injections (CPT 64475, 64476, 64493, 64494, 64495, 0128T, 0216T, and 0217T). To answer certain questions in this analysis, the RFA cohort was further divided into two sub-cohorts based on whether patients were continuously enrolled in the MarketScan database for at least three years prior to their first recorded RFAs. Three years of continuous enrollment without an RFA was chosen in order to define a patient’s first recorded RFA as an „index‟ RFA. The lumbar facet injection cohort was also further divided based on having at least 1 year of enrollment time after their injections and the receipt of a subsequent RFA. At least one year of post-injection enrollment was chosen to determine whether patients went on to receive subsequent injections or RFA (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

This flowchart depicts the study’s inclusion criteria and sample sizes. These cohorts are overlapping, as many patients received lumbar facet injections then lumbar RFA.

Abbreviations: RFA – radiofrequency ablation.

Demographics:

Patient demographic data abstracted included age, sex, employment status, type of health insurance plan, Census Bureau geographic region, and Charlson Comorbidity Score.35,36 Distributions of these data were compared to the entire MarketScan cohort of patients who did not undergo RFA.

Utilization:

To determine the number of lumbar RFA procedures patients underwent, all lumbar RFA procedures performed on the same date, for the same patient, were considered to be a single RFA procedure. Similarly, all lumbar facet injections on the same date, for the same patient, were considered to be a single lumbar facet injection procedure. To count the number of individual facets treated during each procedure and determine laterality, individual insurance claims were analyzed. To avoid inaccuracies created by circumstances such as separate claims for the same procedure made by providers and facilities, coding rules were applied, guided by coding best practices (Supplemental File 1).37–39 Lastly, unilateral and bilateral procedure counts greater than five and ten, respectively, were excluded from the procedure count analysis, as these values reflect the number of total possible spinal levels for unilateral and bilateral facet procedures, respectively, between L1-S1.

To determine the number of lumbar facet joint injection procedures in which patients received a corticosteroid, encounters with one of the following medications recorded were included: betamethasone, dexamethasone, methylprednisolone, prednisone, prednisolone, and triamcinolone.

Cost Analysis:

The MarketScan databases contain gross payment totals paid by the patient and insurance plan for each claim. For each lumbar RFA and lumbar facet injection procedure, all claims were summed to determine the total costs for the procedure.

Statistical Analysis:

Lumbar RFA rates per 100,000 enrollees, for each subgroup, were determined by dividing the number of lumbar RFA sessions in that subgroup by the number of individuals in that subgroup in the whole MarketScan population, multiplied by 100,000.

To determine the MarketScan population‟s distribution of Charlson Comorbidity Scores, which were based on healthcare utilization for one year, a random sample of 150,000 patients with at least one year of MarketScan enrollment was chosen. This sample size was chosen, because it is the same order of magnitude as the RFA cohort population and roughly 0.1% of the MarketScan population.

For procedure counts, the mean, median, and interquartile range of lumbar facet targeted and costs were calculated by year and laterality, as well as overall. All costs were inflated to 2018 US dollars.40

Results:

From 2007 – 2016, the MarketScan database included 149,831,011 unique patients. 165,734 of them received lumbar RFA, while 501,273 patients received lumbar facet injections. Notably, lumbar RFA rates were dramatically higher in older age groups, with rates being 20-fold higher in patients aged 65–74 compared to those under 35 (Table 1). RFA rates were also higher in females compared to males, those on long term disability, and patients covered by comprehensive insurance plans. Geographic variation was also evident. In the Northeast, only 84 patients received RFA per 100,000 enrollees, while in the South utilization was 56% higher with 131 patients receiving RFA per 100,000 enrollees. Lastly, RFA rates were highest in patients with Charlson Comorbidity Scores in the 3 – 4 range.

Table 1:

These are the descriptive characteristics of patients who received RFA in the MarketScan database compared to those who did not.

| RFA Cohort n (%) | Non-RFA Cohort n (%) | RFA Rate per 100,000 Enrollees | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 165,734 (100.0) | 149,665,356 (100.0) | 111 |

| Age (Years) | |||

| < 35 | 15,177 (9.2) | 83,983,167 (56.1) | 18 |

| 35 – 44 | 31,386 (18.9) | 23,927,326 (16.0) | 131 |

| 45 – 54 | 55,773 (33.7) | 23,819,717 (15.9) | 234 |

| 55 – 64 | 63,342 (38.2) | 17,919,831 (12.0) | 352 |

| 65 – 74 | 56 (0.0) | 15,315 (0.0) | 364 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 99,418 (60.0) | 76,326,706 (51.0) | 130 |

| Male | 66,316 (40.0) | 73,338,650 (49.0) | 90 |

| Employment Status | |||

| Full Time | 62,727 (37.8) | 52,414,298 (35.0) | 120 |

| Part Time | 1,133 (0.7) | 1,246,824 (0.8) | 91 |

| Retired | 14,797 (8.9) | 2,908,233 (1.9) | 506 |

| Long Term Disability | 1,365 (0.8) | 89,516 (0.1) | 1,502 |

| Other/Unknown | 85,712 (51.7) | 93,006,485 (62.1) | 92 |

| Health Insurance Plan | |||

| Comprehensive | 5,379 (3.2) | 1,662,695 (1.1) | 322 |

| Exclusive/PPO | 106,546 (64.3) | 69,071,402 (46.2) | 154 |

| HMO | 19,397 (11.7) | 13,381,730 (8.9) | 145 |

| POS | 13,879 (8.4) | 7,056,669 (4.7) | 196 |

| CDHD | 11,950 (7.2) | 7,689,095 (5.1) | 155 |

| Unknown | 8,583 (5.2) | 50,803,765 (33.9) | 17 |

| Geographic Region | |||

| Northeast | 20,962 (12.6) | 25,018,521 (16.7) | 84 |

| North Central | 36,845 (22.2) | 33,137,110 (22.1) | 111 |

| South | 77,709 (46.9) | 59,218,155 (39.6) | 131 |

| West | 26,902 (16.2) | 27,890,777 (18.6) | 96 |

| Missing | 3,316 (2.0) | 4,400,793 (2.9) | 75 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score* | |||

| 0 | 63,434 (57.9) | 127,371 (84.9) | 76 |

| 1 – 2 | 35,718 (32.6) | 19,399 (12.9) | 280 |

| 3 – 4 | 7,473 (6.8) | 2,251 (1.5) | 502 |

| 5+ | 2,899 (2.6) | 979 (0.7) | 411 |

Abbreviations: RFA - radiofrequency ablation; PPO - exclusive/ preferred provider organization; HMO - health maintenance organization; POS - point of service; CDHD - consumer-directed/high-deductible.

In the RFA cohort, Charlson Comorbidity Scores, for all patients with at least one year of enrollment prior to RFA, were calculated to determine the distribution. One year of enrollment was required to allow for adequate time for comorbidities to be recorded. In the non-RFA cohort, a random sample of 150,000 patients with one year of enrollment (~0.1%) was used to estimate the distribution.

Lumbar Radiofrequency Ablation Cohort:

The number of unique patients receiving lumbar RFA per 100,000 enrollees per year increased from 35 to 53, a 51.4% overall increase (4.7% annually). The total number of lumbar RFA procedures performed per 100,000 enrollees per year similarly increased from 49 to 113, a 130.6% increase (9.7% annually). These yearly trends are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

The number of lumbar facet injection and RFA procedures performed in the MarketScan population by year are shown. “Injections” refers to all lumbar facet injection procedures. “All RFA” refers to all RFA procedures. “Index RFA” refers to all RFA procedures that are not repeat RFAs.

Abbreviations: RFA – radiofrequency ablation

During lumbar RFA procedures, two facets were most commonly targeted. The full distribution is shown in Figure 3A. The mean number of facets targeted during lumbar RFA was 2.6 overall (median = 2, IQR = 2 – 3). This number trended downwards slightly from 2.8 facets (median = 2, IQR = 2 – 4) in 2007 to 2.5 facets (median = 2, IQR = 2 – 3) in 2016. The yearly distribution of lumbar RFA facets targeted is provided in Supplemental File 2. Overall, bilateral lumbar RFA was performed 19.9% of the time. RFA sessions with counts greater than the specified maximums comprised 0.6% of all procedures and were excluded from these results.

Figure 3:

a) Histogram of the number of facets targeted during lumbar radiofrequency ablation procedures from 2007 – 2016. b) Histogram showing the number of facets targeted during lumbar facet injection procedures for the same time period.

Lumbar Facet Injection Cohort:

Lumbar facet injection procedure use increased from 201 to 251 procedures per 100,000 enrollees from 2007 to 2016, a 24.9% overall increase (2.5% annually). During each lumbar facet injection procedure, two to four facets were most commonly targeted, slightly higher than the distribution for lumbar RFA procedures (Figure 3B). Each procedure targeted a mean of 3.0 facets (median = 3, IQR = 2 – 4). The number of facets targeted per session trended upwards from 2.7 (median = 2, IQR = 2 – 4) in 2007 to 3.3 (median = 3, IQR = 2 – 4) in 2016. A complete breakdown of the number of facets targeted by year is provided in Supplemental File 3. Throughout the study period, bilateral procedures were performed 46.1% of the time, which was substantially higher than for lumbar RFA procedures. Lumbar facet injection procedures with counts greater than the specified maximums comprised 0.3% of all procedures and were excluded from these results.

Overall, 41.0% of lumbar facet injections were combined with a corticosteroid (Table 2). Steroid administration appeared to grow quickly from 2007 to 2011, increasing from a 34.2% use rate to 44.2%. Growth in steroid usage ceased, however, with rates settling at 40.5% by 2016.

Table 2:

Yearly trend in the inclusion of corticosteroids with facet injections.

| Year | Facet Injections with Corticosteroids n (%) | Facet Injections without Corticosteroids n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 24,136 (34.2%) | 46,448 (65.8%) |

| 2008 | 39,727 (37.1%) | 67,299 (62.9%) |

| 2009 | 46,115 (39.3%) | 71,246 (60.7%) |

| 2010 | 40,587 (40.4%) | 59,864 (59.6%) |

| 2011 | 52,186 (44.2%) | 65,866 (55.8%) |

| 2012 | 51,407 (42.9%) | 68,482 (57.1%) |

| 2013 | 42,944 (43.4%) | 56,061 (56.6%) |

| 2014 | 47,395 (43.3%) | 62,024 (56.7%) |

| 2015 | 29,579 (41.9%) | 41,022 (58.1%) |

| 2016 | 28,425 (40.5%) | 41,727 (59.5%) |

| Total | 402,501 (41.0%) | 580,039 (59.0%) |

Of all patients who received a lumbar facet injection procedure and remained enrolled in the MarketScan databases for at least one year, 44.7% did not receive a subsequent lumbar facet injection or RFA in the year after their first injection, and 28.6% of patients received a subsequent lumbar facet injection, but not lumbar RFA, within the following year. The number of patients receiving lumbar RFA after a lumbar facet injection was 26.7% overall, but this fraction trended upwards from 23.2% in 2007 to 33.5% in 2015.

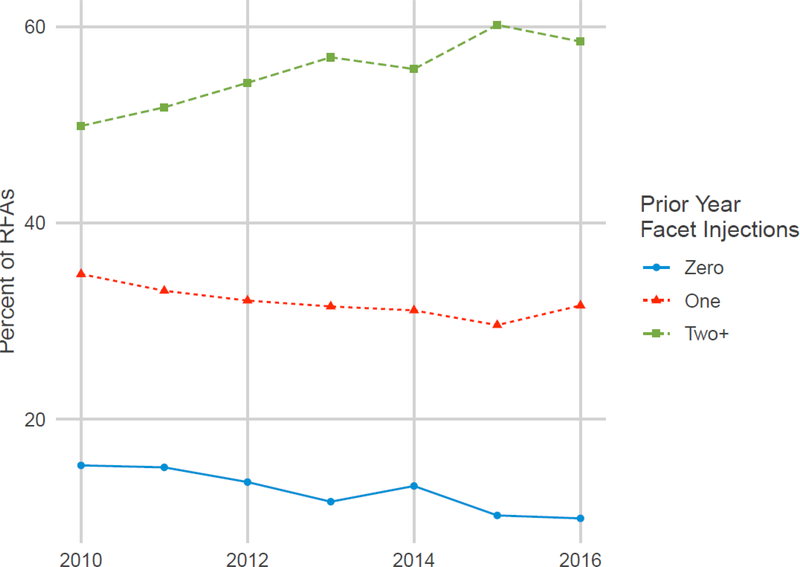

Trends in the percent of patients receiving zero, one, or two lumbar facet injections prior to index lumbar RFA are shown in Figure 4. A majority of patients had two lumbar facet injection procedures prior to their index RFAs, but the group of patients with less than two lumbar facet injection sessions was substantial. Nevertheless, the number of patients receiving two lumbar facet injection procedures prior to RFA grew from 51.1% in 2010 to 58.8% in 2016.

Figure 4:

This is a trend showing the percent of RFAs that were preceded by zero, one, or two or more facet injections in the prior year. The trend starts in 2010, because three years of continuous enrollment was required to label the first recorded RFA as an index RFA, for which prior diagnostic facet injections would be expected.

Abbreviations: RFA – radiofrequency ablation.

Cost Analysis:

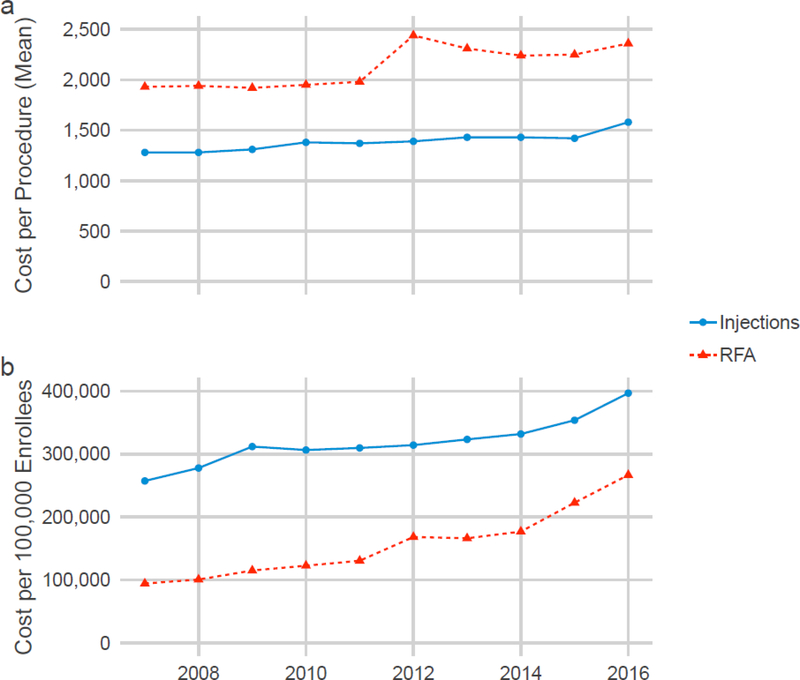

The cost per lumbar RFA and facet injection procedure increased from 2007 to 2016. The mean lumbar RFA procedure cost in 2007 was $1,930 (median = $1,350, IQR = $790 - $2,200), and by 2016 it grew to $2,360 (median = $1,440, IQR = $860 - $2,680), a 2.3% annual increase. Mean costs by year are shown in Figure 5A. In 2007, the mean lumbar facet injection procedure cost was $1,280 (median = $900, IQR = $520 - $1,500). In 2016, the mean lumbar facet injection procedure cost was $1,580 (median = $800, IQR = $450 - $1,670), a 2.4% annual increase.

Figure 5:

a) Mean cost of lumbar facet injection and RFA procedures by year adjusted to 2018 US dollars. b) Overall annual expenditure in the MarketScan population on lumbar facet injections and RFA per 100,000 enrollees, also adjusted to 2018 US dollars.

Abbreviations: RFA – radiofrequency ablation.

Because the cost per procedure and the number of procedures per 100,000 enrollees both increased over time, for each procedure, the cost per 100,000 enrollees increased as well. For lumbar RFA, the cost per 100,000 enrollees went from $94,570 in 2007 to $266,680 in 2016, a 12.2% annual increase. For lumbar facet injections, the cost per 100,000 enrollees went from $257,280 in 2007 to $396,580 in 2016, a 4.9% annual increase. Overall costs by year are presented in Figure 5B.

Discussion:

This study shows consistent growth in both the frequency and per procedure cost of lumbar RFA and facet joint injections among a large, national, commercially insured population from 2007 to 2016. The number of lumbar RFA procedures increased at a 9.7% annual rate, and the cost per procedure increased 2.3% annually. With the combination of these increases, the overall annual expenditure for lumbar RFA grew at a 12.2% annual rate. Lumbar facet injection procedures increased at a 2.5% annual rate, and their cost per procedure also increased at a 2.4% annual rate. Together, this led to a 4.9% annual increase in overall expenditures for lumbar facet injection procedures.

To our knowledge, this is the first study examining utilization trends in lumbar RFA and facet joint injections in commercially insured patients. Similar studies of the Medicare population show slightly slower growth rates for these procedures during the years examined in the current study.14,15,41 In Medicare patients from 2007 – 2011, lumbar RFA utilization grew at a 6.5% annual rate.14 One study found lumbar facet injection utilization grew 1.5% annually from 2007 – 2011, but another found that lumbar facet injections declined from 2007 – 2012 by 2.0% annually.14,41 Higher growth rates in the privately insured population may be secondary to variable, less restrictive insurance coverage requirements compared to Medicare.

A portion of the growth in lumbar facet injection procedures over time is attributable to the growth in RFA. Additionally, the proportion of patients receiving two lumbar facet injection procedures prior to RFA is increasing. Two lumbar facet injection procedures were performed prior to RFA in 51.1% of patients in 2010. By 2016, this number grew to 58.8%. This may reflect physicians using more rigorous pre-RFA selection criteria. Nevertheless, the trend towards a larger proportion of patients receiving two lumbar facet injection procedures prior to lumbar RFA appears to have plateaued since 2013, but the overall growth in the rate at which lumbar facet injections are performed has not. This suggests growth is not fully explained by more physicians using two lumbar facet injection procedures before RFA. An increase in the prevalence of chronic low back pain, recognition of interventional treatment options for it, or usage of alternatives to opioids in the setting of the opioid epidemic, may in part account for this observation.

With increased lumbar facet injection utilization, a higher percentage of people receiving injections are moving on to receive lumbar RFA over time. In 2007, only 23.2% of patients who received a lumbar facet injection underwent subsequent RFA within one year. This fraction grew to 33.5% by 2015, a 4.7% annual increase. It is unclear what is causing this change. More stringent RFA selection criteria, with more patients receiving two diagnostic lumbar facet injection procedures prior to RFA instead of one, should theoretically cause the rate at which patients advance to RFA to decrease. One possibility is a reduction in the use of therapeutic lumbar facet injections, with a concomitant increase in the use of diagnostic lumbar facet injections as a route to definitive treatment with RFA, as evidence has mounted questioning the effectiveness of therapeutic lumbar facet injections.22,29,42–44 Increasing tendencies to limit opioids by providers and patients may also be motivating a higher intervention rate. Another explanation is that provider and/or insurer definitions of positive diagnostic MBBs, MBBs which typically provide 50 – 80% improvement in the back pain numerical rating score and suggest facet-mediated back pain, have become more lenient, despite clinical practice guideline recommendations.25 With diagnostic MBBs, there is room for interpretation on the part of the provider and patient. Unfortunately, insurance claims data do not indicate which pain improvement thresholds providers used.

Another notable finding of this analysis was the difference in the number of facets targeted during lumbar facet injection procedures compared to RFA sessions. A majority of RFAs were unilateral, two-level procedures, while injections were more likely to be bilateral and cover up to four levels. This suggests that patients who presented with a higher number of painful sites may have been less likely to have facet-mediated pain, and thus positive lumbar facet injections, and progress to RFA. Part of this difference, however, may also be an artifact of some insurance providers restricting reimbursement for lumbar RFA to a limited number of facets per procedure. This can lead providers to split RFA procedures into two sessions, days to weeks apart, and falsely reduce the mean number of facets treated per day.

There are several limitations to this study. The MarketScan population encompasses a large number of employer-covered patients in the US, however, it is not necessarily representative of the entire US population. Patients covered by Medicaid and Medicare, as well as those who self-pay, are excluded.34 Additionally, while the CPT codes for lumbar RFA are specific, the codes for lumbar facet injections do not distinguish between a broader set of procedures. Facet injections can include diagnostic MBBs, MBBs including corticosteroid, and intraarticular facet injections that also commonly include corticosteroid.45,46 Despite this lack of specificity, all three of these procedures are interventions for facet-mediated chronic LBP and are used to screen patients as candidates for lumbar RFA, despite lacking clinical practice guideline endorsement, thus making them relevant to this analysis.25 Lastly, there are potential inaccuracies with any administrative dataset, though datasets related to payments for procedures are thought to be highly accurate.47 Furthermore, since there is no reason to think that accuracy would vary over time, yearly trends over thousands of patients are likely to represent actual changes.

Conclusions:

This analysis shows continued growth in the use and cost of lumbar facet injections and lumbar RFA for facet-mediated chronic low back pain. With uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of lumbar RFA, in part due to provider-level variation in adherence to clinical practice guidelines, refinement and use of evidence-based treatment algorithms are needed to responsibly provide care and control inappropriate use of this procedure.30 Future research into RFA success rates, stratified by guideline-concordant care, may be useful to evaluate best practice recommendations. Additionally, delineating the effects of specific insurance regulations on guideline adherence rates may provide a blueprint for improving adherence broadly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the University of Washington CLEAR Center. The UW CLEAR Center is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AR072572. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: Socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88 Suppl 2:21–24. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–2037. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1002/art.34347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin BI, Turner JA, Mirza SK, Lee MJ, Comstock BA, Deyo RA. Trends in health care expenditures, utilization, and health status among US adults with spine problems, 1997–2006. Spine. 2009;34(19):2077–2084. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b1fad1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CJL, Atkinson C, Bhalla K, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suri P, Hunter DJ, Rainville J, Guermazi A, Katz JN. Presence and extent of severe facet joint osteoarthritis are associated with back pain in older adults. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(9):11991206 Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gellhorn AC, Katz JN, Suri P. Osteoarthritis of the spine: The facet joints. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(4):216–224. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SP, Raja SN. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(3):591–614. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suri P, Miyakoshi A, Hunter DJ, et al. Does lumbar spinal degeneration begin with the anterior structures? A study of the observed epidemiology in a community-based population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2011;12:202 Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophysial joints. is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine. 1994;19(10):1132–1137. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Revel M, Poiraudeau S, Auleley GR, et al. Capacity of the clinical picture to characterize low back pain relieved by facet joint anesthesia. proposed criteria to identify patients with painful facet joints. Spine. 1998;23(18):1976; discussion 1977. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwarzer AC, Wang SC, O’Driscoll D, Harrington T, Bogduk N, Laurent R. The ability of computed tomography to identify a painful zygapophysial joint in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20(8):907–912. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarzer AC, Wang SC, Bogduk N, McNaught PJ, Laurent R. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophysial joint pain: A study in an australian population with chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(2):100–106. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarzer AC, Derby R, Aprill CN, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. Pain from the lumbar zygapophysial joints: A test of two models. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7(4):331–336. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Singh V, Falco FJE. Assessment of the escalating growth of facet joint interventions in the medicare population in the united states from 2000 to 2011. Pain Physician. 2013;16(4):365 Accessed Sep 30, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Falco FJE, Hirsch JA. An updated assessment of utilization of interventional pain management techniques in the medicare population: 2000 – 2013. Pain Physician. 2015;18(2):115 Accessed Sep 30, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen SP, Huang JHY, Brummett C. Facet joint pain--advances in patient selection and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(2):101–116. Accessed Sep 30, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lakemeier S, Lind M, Schultz W, et al. A comparison of intraarticular lumbar facet joint steroid injections and lumbar facet joint radiofrequency denervation in the treatment of low back pain: A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(1):228–235. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182910c4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shabat S, Leitner Y, Bartal G, Folman Y. Radiofrequency treatment has a beneficial role in reducing low back pain due to facet syndrome in octogenarians or older. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:737–740. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S44999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Pampati V, Boswell MV. Utilization of facet joint and sacroiliac joint interventions in medicare population from 2000 to 2014: Explosive growth continues! Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(10):58 Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11916-016-0588-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, Joshi A, McLarty J, Bogduk N. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Spine. 2000;25(10):1270–1277. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen SP, Chen Y, Neufeld NJ. Sacroiliac joint pain: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(1):99–116. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Kleef M, Vanelderen P, Cohen SP, Lataster A, Van Zundert J, Mekhail N. 12. pain originating from the lumbar facet joints. Pain Pract. 2010;10(5):459–469. Accessed Sep 30, 2018. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2010.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manchikanti L, Kaye AD, Boswell MV, et al. A systematic review and best evidence synthesis of the effectiveness of therapeutic facet joint interventions in managing chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2015;18(4):535 Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leggett LE, Soril LJJ, Lorenzetti DL, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for chronic low back pain: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(5):146 Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bogduk N ISIS practice guidelines for spinal diagnostic and treatment procedures. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: International Spine Intervention Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Tilburg CWJ, Stronks DL, Groeneweg JG, Huygen FJPM Randomized shamcontrolled, double-blind, multicenter clinical trial on the effect of percutaneous radiofrequency at the ramus communicans for lumbar disc pain. Eur J Pain. 2017;21(3):520–529. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1002/ejp.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maas ET, Ostelo, Raymond WJG, Niemisto L, et al. Radiofrequency denervation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(10):CD008572 Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008572.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poetscher AW, Gentil AF, Lenza M, Ferretti M. Radiofrequency denervation for facet joint low back pain: A systematic review. Spine. 2014;39(14):842 Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou R Low back pain (chronic). BMJ Clin Evid. 2010;2010. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juch JNS, Maas ET, Ostelo, Raymond WJG, et al. Effect of radiofrequency denervation on pain intensity among patients with chronic low back pain: The mint randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2017;318(1):68–81. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen SP, Williams KA, Kurihara C, et al. Multicenter, randomized, comparative cost-effectiveness study comparing 0, 1, and 2 diagnostic medial branch (facet joint nerve) block treatment paradigms before lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(2):395–405. Accessed Sep 13, 2018. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e33ae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogduk N, Holmes S. Controlled zygapophysial joint blocks: The travesty of cost-effectiveness. Pain Med. 2000;1(1):24–34. Accessed Sep 13, 2018. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.99104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novak S, Nemeth WC. RE: Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic medial branch blocks before radiofrequency denervation. Spine J. 2008;8(2):412–413. Accessed Sep 13, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansen LG, Chang S. Health research for the real world: The marketscan databases. Truven Health Analytics. 2011:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Census bureau regions and divisions with state FIPS codes. Census.gov Web site. https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/maps/reg_div.txt. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 37.Commercial claims and encounters medicare supplemental. Truven Health Analytics. 2014:1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 38.How to use the medicare national correct coding initiative (NCCI) tools. CMS.gov Web site. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/How-To-Use-NCCI-Tools.pdf. Updated 2018. Accessed September 14, 2018.

- 39.15 CPT and coding issues for orthopedics and spine ASC facilities.. 2012:1–18.

- 40.US Department of Labor. CPI-all urban consumers (current series). BLS.gov Web site. https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CUUR0000SAM. Accessed September 10, 2018.

- 41.Beckworth WJ, Jiang M, Hemingway J, Hughes D, Staggs D. Facet injection trends in the medicare population and the impact of bundling codes. Spine J. 2016;16(9):1037–1041. Accessed Sep 30, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen SP, Huang JHY, Brummett C. Facet joint pain--advances in patient selection and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(2):101–116. Accessed Aug 14, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chou R, Hashimoto R, Friedly J, et al. Pain management injection therapies for low back pain. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285206/. Accessed Sep 30, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vekaria R, Bhatt R, Ellard DR, Henschke N, Underwood M, Sandhu H. Intra-articular facet joint injections for low back pain: A systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2016;25(4):1266–1281. Accessed Sep 30, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00586-016-4455-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paravertebral facet joint blocks. CMS.gov Web site. https://downloads.cms.gov/medicarecoverage-database/lcd_attachments/29252_7/64490.2_codeguide.htm. Updated 2011. Accessed September 14, 2018.

- 46.Epidural steroid and facet injections for spinal pain. OXHP.com Web site. https://www.oxhp.com/secure/policy/epidural_steroid_and_facet_joint_injections_for_spinal_pain.pdf. Updated 2018. Accessed September 14, 2018.

- 47.Fisher ES, Whaley FS, Krushat WM, et al. The accuracy of medicare’s hospital claims data: Progress has been made, but problems remain. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(2):243–248. Accessed Sep 30, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.