Abstract

Objective(s):

A pathological complete response (pCR) in patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer after chemoradiotherapy and surgery (CRT-S) is associated with improved overall and disease-free survival. Nevertheless, approximately one-third of patients with a pCR still recur. The aim of this study was to evaluate risk factors and patterns of recurrence in locally advanced esophageal cancer patients who achieved a pCR following CRT-S.

Methods:

We performed a retrospective review of a single-institution database of 233 patients with stage II and III esophageal cancer with a pCR after CRT-S between 1997 and 2017. A multivariable competing risk-regression model was used to identify predictors of recurrence.

Results:

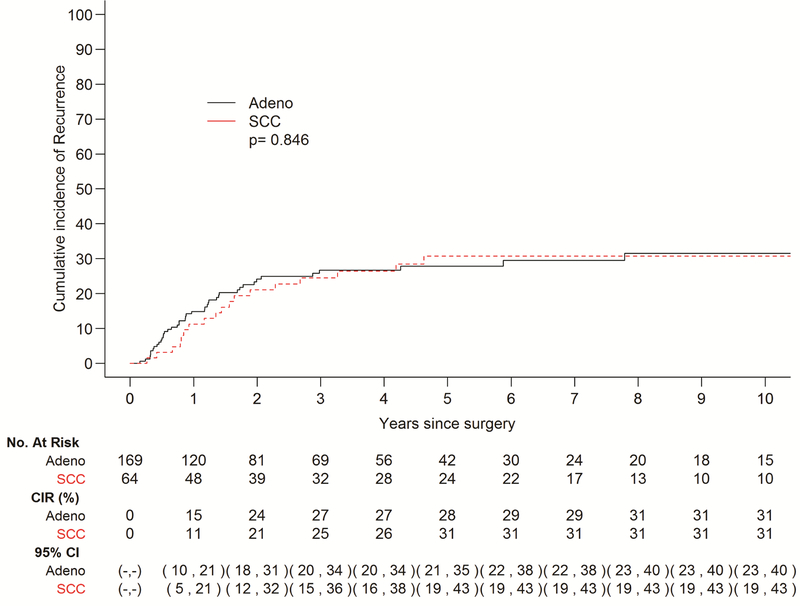

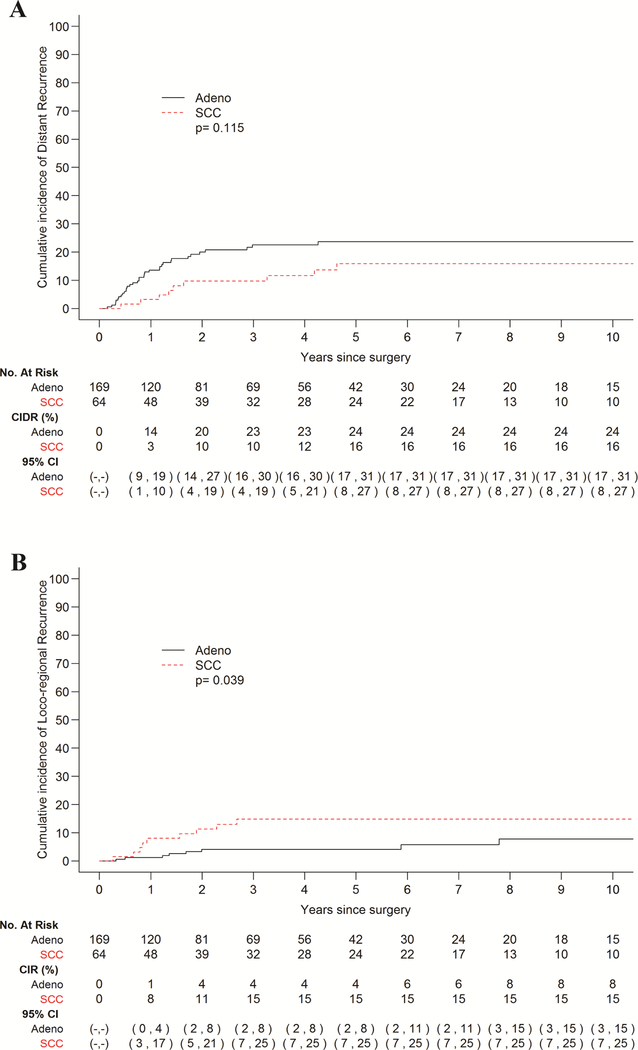

A total of 61 patients exhibited recurrence in this cohort, 43 with adenocarcinoma (EAC) and 18 with squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Five-year cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) did not vary by histology. Univariable analysis revealed that poor tumor differentiation (HR 2.28, p=0.022) and advanced clinical stage (HR 1.89, p=0.042) are predictors of recurrence in the EAC subgroup, while poor tumor differentiation remained the only independent predictor on multivariable analysis in the entire cohort (HR 2.28, p=0.009). Patients with EAC had a higher incidence of distant recurrences, while patients with ESCC demonstrated a higher incidence of loco-regional recurrence (p=0.039).

Conclusions:

Poor tumor differentiation is an independent risk factor for recurrence in esophageal cancer patients with a pCR. While there is no difference in the CIR between EAC and ESCC, patterns of recurrence appear to differ. Thus, treatment and surveillance strategies may be tailored appropriately.

Introduction

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery (CRT-S) has been widely established as standard of care for patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer. This tri-modal approach has been shown to facilitate radical resection and improve both overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS).1–3 Esophageal cancers are divided into 2 primary histologies worldwide: squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), which is far more prevalent in Asia and developing nations, and adenocarcinoma (EAC), which accounts for the vast majority of cases in the United States owing to rising rates of obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease.4 Integrated analyses from the Cancer Genome Atlas suggest distinct mutational signatures and genetic underpinnings associated with these two histologies, and in fact, distinct clinical outcomes in terms of treatment response and survival are similarly observed.5

Following CRT-S, approximately 45% of patients with ESCC and 25% of patients with EAC achieve a pathological complete response (pCR), defined as no histological evidence of tumor in the surgical specimen.1, 6 The degree of response to chemoradiotherapy is a strong predictor of both OS and DFS, and several studies have demonstrated that patients with a pCR have better overall and disease free survival and lower rates of recurrence in comparison to patients with residual disease contained in the surgical specimen despite complete resection.7–9 In particular, for patients with pCR, 5-year OS and DFS has been reported to be near or above 50% regardless of histology.10–13

Despite these positive results, 21–39% of patients who achieve pCR do recur, predominantly within 2 years post-treatment.8–10 Whether such patients with early recurrences truly had no evidence of residual disease following CRT-S certainly remains a valid question, as misclassification of minimal residual disease is possible. However, if they were correctly designated as having a pCR, then underlying clinical characteristics and tumor biology that predispose to recurrence are worth exploring in order to better risk stratify patients. Though patients with ESCC do exhibit higher rates of chemosensitivity and pCR with lower rates of distant failure in comparison to patients with EAC, little is known about clinical factors associated with risk of disease recurrence in this unique subset of patients with pCR, as well as the impact of histology on outcomes. Significant heterogeneity exists among the few studies that have investigated this area. For instance, Luc and colleagues found that EAC histology and grade 3–4 postoperative complications were the only clinical factors significantly associated with recurrence in pCR patients.14 In another retrospective study of 70 patients with ESCC and pCR, advanced clinical tumor stage (i.e., T3–4) was the only independent risk factor for recurrence.15 However, in a larger multi-center study including 299 patients with pCR, no significant clinical or pathological risk factors for recurrence were identified.10

Understanding both the risk factors and patterns of recurrence in patients who achieved a pCR can provide insight into optimization of both systemic and local therapies, as well as appropriate surveillance intervals and strategies. In fact, while it is well established that response to chemoradiation therapy affects the rate of recurrence overall, whether the site of recurrence differs between patients with and without pCR is unclear.7, 8, 11, 13 Thus, the aim of the current study was to evaluate both risk factors and patterns of recurrence in patients who achieved pCR following CRT-S for locally advanced esophageal cancer. In addition, patterns of recurrence were also compared between EAC and ESCC cohorts to examine differences related to tumor histology.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

All patients with clinical stage II and III esophageal cancer treated with CRT-S who achieved pCR from 1997 to 2017 were identified using a prospectively maintained database by the Thoracic Surgery Service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Patients who received either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy alone, or salvage esophagectomy after definitive chemoradiotherapy were excluded. Patients with missing survival data and tumors of the cervical esophagus were also excluded. (Supplemental Fig. 1) This study was reviewed and approved by our Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was waived.

Variables

The following variables were available for comparison in our study: age, sex, race, comorbidities, tumor histology, endoscopic length of tumor, pathologic length of tumor bed, length of proximal and distal margins, clinical and pathological stage, treatment regimen, surgical complications, recurrence, and survival status. The entire pathologic specimen was submitted for pathologic examination. Tumor location was determined by the distance of proximal edge of the lesion from the incisors. The endoscopic length of the tumor was calculated when both proximal and distal edges of lesion were recorded. Clinical and pathological stage was classified according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual. Pre-treatment staging assessment was performed using EUS, and computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). All patients received concurrent neoadjuvant chemoradiation. Induction chemotherapy prior to chemoradiation was given to a subset of patients.

A pCR was defined as complete absence of viable tumor grossly and microscopically in the entire surgical specimen consisting of the resected esophagus and all harvested lymph nodes.16 Presence of residual lesions such as Barrett’s metaplasia, high-grade, or low-grade dysplasia was recorded.

The standard protocol for recurrence surveillance at our institution is at the discretion of the provider, but usually includes a clinical assessment and a CT chest/ abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast every 3–6 months for the first 2 years after surgery. Yearly scans are done thereafter for 5 years. Routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is not performed, except in cases of clinical symptoms or suspicious imaging. Some patients who resided far from the Institution underwent follow up with their local physician.

Recurrence within the esophagus or stomach, mediastinal, periesophageal, gastric, celiac, and/or supraclavicular lymph nodes was classified as loco-regional recurrence (LRR); all other sites were classified as distant recurrence. When both LRR and distant recurrence were identified at the same time the patient was classified as having distant recurrence.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages and compared using Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables were summarized as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Time to recurrence was calculated from the date of surgery until the date of recurrence, death or last follow-up. Death without a recurrence was considered a competing risk event. The cumulative incidence of recurrence was estimated using a cumulative incidence function. Site-specific recurrences were also estimated with cumulative incidence functions such that a recurrence at a different site and death without recurrence were considered competing risks. Comparisons between histology groups were assessed using Gray’s test.

Risk factors for recurrence were evaluated using Fine-Gray competing risk regression methods.17 Clinically relevant variables with a p-value <0.2 on univariable analysis were incorporated into the multivariable model. Due to the limited number of events in the EAC subtype, only variables with p-value <0.05 were fitted in the final model and in the ESCC subtype, we a priori selected clinically important variables for evaluation in univariable analysis. No multivariable analysis was performed on the ESCC subtype. OS and DFS following surgery were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods and compared by histology groups using a log-rank test. The threshold for significance was set at p<0.05 (two-sided). Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R 3.2.4 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 233 patients with esophageal cancer (169 with EAC, 64 with ESCC) who achieved pCR after chemoradiotherapy and surgery were included in this study after exclusion criteria were applied. Patient characteristics overall and by histology are shown in Table 1. Nearly half of patients (46.8%) received induction chemotherapy prior to concurrent chemoradiotherapy, as a PET-directed strategy is currently the standard at our institution as previously described by Ku et al.18 The vast majority of patients received platinum-based chemotherapy (91.0%) and 5040cGy of radiation (82.4%) in the neoadjuvant setting, including 73 (31.3%) patients who received the CROSS trial chemotherapy regimen of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Once tri-modality therapy was completed, no further adjuvant therapies were delivered and patients were subjected to routine surveillance.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, overall and by histology

| Characteristic | Overall (N=233) | Adeno (N=169) | SCC (N=64) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61 (56, 68) | 61 (56, 69) | 59 (55, 66) | 0.153 |

| Sex | <.001 | |||

| M | 184 (79) | 149 (88.2) | 35 (54.7) | |

| F | 49 (21) | 20 (11.8) | 29 (45.3) | |

| Clinical stage | 0.449 | |||

| II | 87 (37.3) | 66 (39.1) | 21 (32.8) | |

| III | 146 (62.7) | 103 (60.9) | 43 (67.2) | |

| Tumor location | <.001 | |||

| Distal/junctional | 196 (84.1) | 164 (97) | 32 (50) | |

| Middle | 37 (15.9) | 5 (3) | 32 (50) | |

| Tumor differentiation | 0.001 | |||

| Well/moderate (Grade 1/2) | 104 (44.6) | 65 (38.5) | 39 (60.9) | |

| Poor (Grade 3) | 111 (47.6) | 92 (54.4) | 19 (29.7) | |

| N/A | 18 (7.7) | 12 (7.1) | 6 (9.4) | |

| Endoscopic tumor length | 5 (3, 6) | 5 (3, 6) | 6 (4, 8) | 0.002 |

| Pre-CRT EUS | 0.016 | |||

| Yes | 195 (83.7) | 148 (87.6) | 47 (73.4) | |

| No | 38 (16.3) | 21 (12.4) | 17 (26.6) | |

| Pre-CRT PET-CT | 0.219 | |||

| Yes | 210 (90.1) | 155 (91.7) | 55 (85.9) | |

| No | 23 (9.9) | 14 (8.3) | 9 (14.1) | |

| Post-CRT PET-CT | 0.004 | |||

| Yes | 162 (69.5) | 127 (75.1) | 35 (54.7) | |

| No | 71 (30.5) | 42 (24.9) | 29 (45.3) | |

| Pre-CRT SUVm | 12.2 (7.3, 17.7) | 11.5 (6.9, 18.1) | 13.2 (8.7, 16.9) | 0.278 |

| Post-CRT SUVm | 3.4 (1, 4.5) | 3.6 (2.2, 4.9) | 1 (0, 3.8) | 0.001 |

| Induction chemotherapy | 0.46 | |||

| Yes | 109 (46.8) | 81 (47.9) | 28 (43.8) | |

| No | 116 (49.8) | 80 (47.3) | 36 (56.2) | |

| N/A | 8 (3.4) | 8 (4.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Chemotherapy regimen | <.001 | |||

| Carboplatin/Paclitaxel (CROSS) | 73 (31.3) | 64 (37.9) | 9 (14.1) | |

| Other Platinum | 139 (59.7) | 88 (52.1) | 51 (79.7) | |

| 5-FU | 14 (6) | 13 (7.7) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Other | 7 (3) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (4.7) | |

| Radiation Dose | 0.527 | |||

| <5040 | 33 (14.2) | 26 (15.4) | 7 (10.9) | |

| >=5040 | 192 (82.4) | 137 (81.1) | 55 (85.9) | |

| N/A | 8 (3.4) | 6 (3.6) | 2 (3.1) | |

| CRT to surgery (wks) | 8 (6.1, 10.0) | 7.86 (6.1, 9.9) | 8.43 (6.6, 10.7) | 0.232 |

| Surgical procedure | <.001 | |||

| Ivor Lewis | 200 (85.8) | 156 (92.3) | 44 (68.8) | |

| Mckeown 3-hole | 25 (10.7) | 7 (4.1) | 18 (28.1) | |

| Gastrectomy | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 7 (3) | 5 (3) | 2 (3.1) | |

| Tumor bed length (cm) | 2.7 (1.8, 3.7) | 2.7 (1.8, 3.7) | 2.5 (1.98, 4) | 0.914 |

| Resected lymph nodes | 20 (15, 27) | 20 (16, 27) | 18 (11, 26.5) | 0.018 |

| Proximal margin (cm) | 5 (3, 7.5) | 5.5 (3.2, 8.5) | 3.5 (2.5, 5.5) | <.001 |

| Distal margin (cm) | 5.5 (4, 7.5) | 5.35 (4, 7) | 6.5 (4, 10) | 0.074 |

| Residual lesion | <.001 | |||

| None | 157 (67.4) | 100 (59.2) | 57 (89.1) | |

| Barrett’s metaplasia | 38 (16.3) | 35 (20.7) | 3 (4.7) | |

| Low grade dysplasia | 19 (8.2) | 17 (10.1) | 2 (3.1) | |

| High grade dysplasia | 19 (8.2) | 17 (10.1) | 2 (3.1) |

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are expressed as number (percent). Adeno = adenocarcinoma, SCC = squamous cell carcinoma, EAC = esophageal adenocarcinoma, ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, CRT = chemoradiotherapy, SUVm = maximum standard uptake value, EUS = endoscopic ultrasound, PET-CT = positron emission tomography-computed tomography, 5-FU = 5-fluorouracil.

In comparison to EAC, ESCC tumors were longer by endoscopic measurement and better differentiated. Half of ESCC tumors were located in the mid-esophagus vs. only 3% of EAC tumors, and accordingly, Mckeown 3-hole esophagectomy was performed more often in patients with ESCC than EAC (28.1% vs. 4.1%), with shorter proximal margins [3.5cm (IQR 2.5–5.5) vs. 5.5cm (3.17–8.5), p=0.001]. A higher number of lymph nodes were retrieved during esophagectomy performed for EAC as compared to ESCC [20 (IQR 16–27) vs. 18 (IQR 11–26.5), p=0.018]. OS and DFS at 5 years for patients in this cohort after pCR were 58% (95% CI 55–72%) and 53% (95% CI 52–68%) for EAC, and 61% (95% CI 51–77%) and 53% (95% CI 46–71%) for ESCC, respectively, and there were no significant difference between histologies. (Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3).

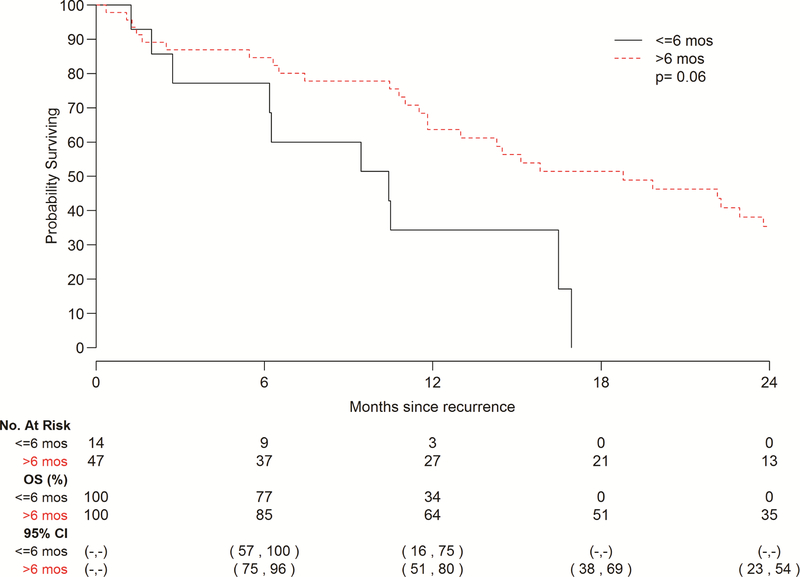

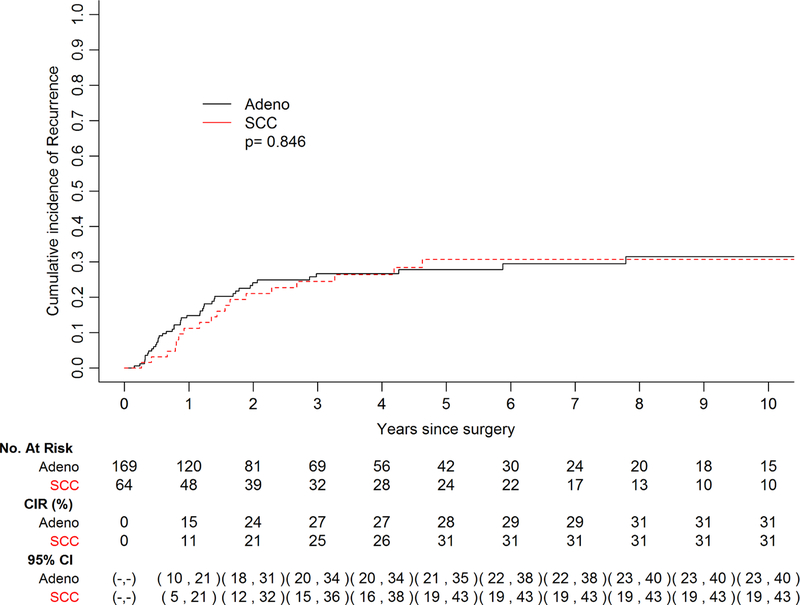

Patterns of Recurrence

A total of 61 patients exhibited recurrence of disease in this cohort, 43 with EAC and 18with ESCC, while 56 patients died without recurrence. Ninety percent patients adhered to our surveillance protocol. Median follow-up among survivors was 42.4 months (range 0.4–213), and median interval to recurrence among patients who recurred was 11.6 months (range 1.8–93.6). The cumulative incidence of recurrence did not vary significantly by histology (p=0.85) (Fig. 1). The 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrence stratified by histology was 28% (95% CI 21–35%) for EAC and 31% (95% CI 19–43%) for ESCC, though the curves begin to plateau at 2 years post-esophagectomy. In terms of site of recurrence, 44 patients recurred at a distant site and 17 recurred loco-regionally. Patients with EAC had a higher incidence of distant recurrence in comparison to those with ESCC (Fig. 2a); with the most common sites being liver and brain (Table 2). Conversely, patients with ESCC demonstrated a higher incidence of LRR (p=0.039) (Fig. 2b), with mediastinal lymph nodes being the most frequent site (Table 2). Among patients who recurred, 14 of 61 recurred within 6 months post-surgery. Patients with disease recurrence within 6 months post-esophagectomy had a significantly worse survival when compared to patients who recurred after 6 months, p=0.007 (Fig. 3). Recurrent disease was treated palliatively in the majority of cases (91%), including chemotherapy in 30 (59%) patients, a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in 5 (10%) patients, surgery alone in 3 (6%) patients, radiotherapy alone in 3 (6%) patients, and immunotherapy in 1 (2%) patient. 9 (18%) patients were treated with both surgery and radiotherapy, 8 of which had brain metastases.

Figure 1 –

Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) stratified by histology. There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of disease recurrence between adenocarcinoma (adeno) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) histologies.

Figure 2 –

Cumulative incidence of distant recurrence (CIDR; A) and loco-regional recurrence (B) stratified by histology. A, Patients with adenocarcinoma (adeno) had a higher incidence of distant recurrences than patients with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), though not statistically significant. B, Conversely, patients with SCC had a higher incidence of loco-regional recurrence than patients with adeno, and this was statistically significant.

Table 2.

Distribution of recurrence sites by histology

| Site of Recurrence | EAC (N=43) | ESCC (N=18) |

|---|---|---|

| Loco-regional: | ||

| Mediastinal LN | 3 (7%) | 6 (33%) |

| Anastomosis/conduit | 1 (2.3%) | 1 (5.5%) |

| Supraclavicular LN | 1 (2.3%) | 2 (11%) |

| Multiple sites | 3 (7%) | 0 |

| Distant: | ||

| Brain | 12 (28%) | 1 (5.5%) |

| Liver | 4 (9.3%) | 2 (11%) |

| Bone | 2 (4.7%) | 0 |

| Retroperitoneal LN | 1 (2.3%) | 0 |

| Lung | 2 (4.7%) | 5 (27.8%) |

| Peritoneum | 1 (2.3%) | 0 |

| Multiple organs | 13 (30.2%) | 1 (5.5%) |

EAC = esophageal adenocarcinoma, ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, LN = lymph node.

Figure 3 –

Overall survival (OS) following recurrence stratified by interval to recurrence. OS was significantly lower in patients that recurred within 6 months post-treatment in comparison to those that recurred beyond this window.

Risk Factors for Recurrence

Results of univariable analysis of risk factors for recurrence in the overall cohort revealed that tumor differentiation grade was the only factor significantly associated with recurrence (HR 1.79, p=0.035) (Supplemental Table 1). In multivariable analysis, poor differentiation (i.e., Grade 3) remained the only independent predictor of recurrence (HR 2.38, p=0.009) (Table 3). Clinical factors were analyzed for association with recurrence for each histological subtype. In univariable analysis for the EAC subgroup, advanced clinical stage (HR 1.92, p=0.048) and poor tumor differentiation (HR 2.28, p=0.022) were both associated with recurrence. Multivariable analysis showed that advanced clinical stage remained important (HR 1.86, p=0.085), but poor tumor differentiation once again was the only independent predictor for developing a recurrence (HR 2.39, p=0.018) (Table 4). In patients with ESCC, no significant risk factors of recurrence were identified on univariable analysis, and multivariable analysis was not performed due to insufficient number of events.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors for recurrence after pathological complete response in overall cohort

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| SUVm pre-treatment Yes vs. No | 0.98 (0.93, 1.02) | 0.33 |

| Tumor length (cm) | 0.84 (0.65, 1.09) | 0.2 |

| Differentiation Poor vs. Well/moderate | 2.42 (1.26, 4.64) | 0.008 |

| Radiation Dose >=5040 vs. <5040 cGy | 1.88 (0.58, 6.11) | 0.29 |

SUVm = maximum standard uptake value.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis of risk factors for recurrence after pathological complete response in esophageal adenocarcinoma

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor grade/differentiation, poor vs. well/moderate | 2.39 | 1.16 – 4.93 | 0.018 |

| Clinical Stage, III vs. II | 1.86 | 0.92 – 3.76 | 0.085 |

| Radiation dose, ≥5040 vs. <5040 | 2.14 | 0.65 – 7.06 | 0.21 |

Discussion

In patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer treated with tri-modality therapy, pCR after esophagectomy portends a positive prognosis in terms of improved survival and a lower rate of recurrence.1, 11 Despite these outcomes, other studies have reported that 21–39% of patients with a pCR still recur.8–10 In our study, 61 patients with pCR experienced recurrence of disease. To date, few studies have assessed whether clinical and pathological characteristics may predict recurrence in this patient population. Here, we demonstrate that poor tumor differentiation grade is an independent predictor of recurrence, particularly in the subgroup of patients with EAC where there was adequate statistical power to detect this result. In addition, on univariable analysis, advanced clinical stage was associated with increased risk of recurrence in EAC patients. These results parallel what others have shown in EAC patients, including both pCR and non-pCR cohorts. For example, Kim et al. showed that early clinical stage is an independent predictor of recurrence-free survival (p=0.01) in patients with a major pathological response.19 Moreover, Xi et al. demonstrated that histologic grade (HR 1.635) and clinical T stage (HR 1.717) were both predictors of recurrence in all patients with EAC, whereas histologic grade was not a risk factor for recurrence for ESCC.6 Our cohort of ESCC patients with pCR, on the other hand, was insufficiently powered to discern any significant risk factors of recurrence. Due to a shift in treatment paradigm favoring definitive chemoradiotherapy over tri-modality therapy in ESCC over time, fewer ESCC patients were eligible for inclusion in this study, though this trend is reversing once again based on recent data from our institution.20 Moreover, our institution’s pCR rate for ESCC is also lower than that reported by others, including the CROSS trial, most likely due to the fact that surgery is almost exclusively performed for high suspicion of residual disease.

Unsurprisingly, our data indicates that overall survival is significantly influenced by the time to recurrence. Though rare, very early recurrences detected within 6 months from CRT-S were associated with significantly worse survival than later recurrences, and this was equivalent between histologies. Most prior studies have shown that there is no significant difference in recurrence pattern, site, timing, DFS, or OS between EAC and ESCC histologies in pCR patients, suggesting that both patient groups should continue to undergo similar treatment and surveillance strategies.6, 10 Only Luc et al. identified EAC histology as a risk factor of recurrence in pCR patients.14

In our study, the median time to recurrence among patients who recurred was 11.6 months, with no differences in the cumulative incidence of recurrence between EAC and ESCC. Both curves in Fig. 1 plateau at 2 years, indicating that nearly all recurrences occur within this time-frame regardless of histology. Xi et al. also found that approximately 80% of recurrences occur within 2 years in a recent report of the MD Anderson pCR cohort.6 Thus, we hypothesize that patients in this group may benefit from more frequent surveillance, potentially every 3–4 months rather than the current approach of every 6 months. Prospective clinical studies are needed to prove that early detection of recurrence leads to improved survival. Furthermore, most patients who recurred presented with distant failure (72%), which is a consistent trend among both pCR and non-pCR patients regardless of histology.11, 21 However, we did observe a significantly higher incidence of LRR in pCR patients with ESCC in comparison to EAC. This finding differs from other studies which have shown no significant difference in LRR rate between pCR patients with ESCC vs. EAC, and supports a role for extended chest imaging combined with upper endoscopy during surveillance.22 Given that the most frequent site of LRR in ESCC patients was mediastinal lymph nodes, a more complete or extensive mediastinal lymphadenectomy during resection may be justified as well to reduce the incidence of LLR. Conversely, we also observed a higher incidence of distant recurrences in EAC vs. ESCC pCR patients, though this did not reach statistical significance. Moreover, the most frequent sites of recurrence in EAC pCR patients were liver and brain. Fields and colleagues have reported that one-third of recurrences in gastroesophageal cancer patients with a pCR occur in the brain.23 Similarly, a recent study of the MD Anderson experience found a 25% rate of brain recurrences in pCR patients (vs. 7% in non-pCR patients).7 As brain scans, either CT or magnetic resonance imaging, are not part of the staging or surveillance routine in esophageal cancer patients and are only performed when neurologic symptoms arise, this number is likely to be under-reported. However, these findings indicate that axial imaging of the brain should be considered along with CT or PET-CT as part of the routine surveillance strategy in EAC pCR patients.

Our study has several limitations including its retrospective design and its relatively small number of patients, particularly in the ESCC cohort. Moreover, the study period spans over 20 years, during which there was considerable variability in staging modalities, chemotherapy regimens, use of induction chemotherapy, and surgical role and technique. Additionally, a small group of patients were not compliant with our standard follow-up protocol. Overall, however, our study is based on one of the largest single-center cohort of patients with pCR and includes both EAC and ESCC histologies with a comparison between them.

In conclusion, pCR is not necessarily synonymous with cure, as the risk of recurrence remains substantial. Poor tumor differentiation grade represents an independent risk factor for recurrence in pCR patients, particularly those with EAC, and the majority of these patients recur at distant sites within a 2-year period after treatment. In contrast, pCR patients with ESCC have a significantly higher rate of LRR. This is the first study to show a divergence in patterns of recurrence in pCR patients by histology, and this may guide treatment and surveillance strategies in the future.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1 – Study cohort, with excluded patients.

Supplemental Figure 2 – Overall survival (OS) by histology. OS in patients with adenocarcinoma (adeno) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) does not differ significantly and approaches 60% at 5 years.

Supplemental Figure 3 – Disease-free survival (DFS) by histology. DFS in patients with adenocarcinoma (adeno) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) does not differ significantly and approaches 53% at 5 years.

Video Legend: Smita Sihag, MD, MPH

Central Picture:

Cumulative incidence of recurrence after pathologic complete response, by histology.

Central Message:

While risk factors and the cumulative incidence of recurrence after a pathological complete response to chemoradiotherapy plus surgery do not vary by histology, patterns of recurrence appear to differ.

Perspective Statement:

Few studies have examined recurrence patterns in patients with complete pathological response following trimodality therapy with comparison by histology. Though the rate of long-term cure is higher in this cohort, our study suggests patients with poorly differentiated tumors have a higher recurrence rate and perhaps should undergo more aggressive surveillance during the initial 2-year period after treatment in accordance to histologic subtype.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported, in part, by NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. A.B. is supported by a Surgeon Development award from the Esophageal Cancer Education Foundation (ECEF).

Glossary of abbreviations:

- EAC

Esophageal adenocarcinoma

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- CRT-S

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery

- pCR

Pathological complete response

- OS

Overall survival

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- IQR

Interquartile range

- CIR

Cumulative incidence of recurrence

- SUVm

Maximum standardized uptake value

- EUS

Endoscopic ultrasound

- CT

Computed tomography

- PET-CT

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- LRR

Loco-regional recurrence

Biographies

Dr Arianna Barbetta

Dr Jules Lin

Dr Virginia Litle

Dr Daniela Molena

Dr Siva Raja

Dr Brendon Stiles

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu B, Bo Y, Wang K, et al. Concurrent neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy could improve survival outcomes for patients with esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis based on random clinical trials. Oncotarget 2017;8:20410–20417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebski V, Burmeister B, Smithers BM, Foo K, Zalcberg J, Simes J. Survival benefits from neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy in oesophageal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology 2007;8:226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Napier KJ, Scheerer M, Misra S. Esophageal cancer: A Review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, staging workup and treatment modalities. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2014;6:112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Analysis Working Group: Asan U, Agency BCC, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 2017;541:169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xi M, Yang Y, Zhang L, et al. Multi-institutional Analysis of Recurrence and Survival After Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy of Esophageal Cancer: Impact of Histology on Recurrence Patterns and Outcomes. Ann Surg 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Blum Murphy M, Xiao L, Patel VR, et al. Pathological complete response in patients with esophageal cancer after the trimodality approach: The association with baseline variables and survival-The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer 2017;123:4106–4113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meguid RA, Hooker CM, Taylor JT, et al. Recurrence after neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgery for esophageal cancer: does the pattern of recurrence differ for patients with complete response and those with partial or no response? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;138:1309–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jipping KM, Hulshoff JB, van Amerongen EA, Bright TI, Watson DI, Plukker JTM. Influence of tumor response and treatment schedule on the distribution of tumor recurrence in esophageal cancer patients treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. J Surg Oncol 2017;116:1096–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallbohmer D, Holscher AH, DeMeester S, et al. A multicenter study of survival after neoadjuvant radiotherapy/chemotherapy and esophagectomy for ypT0N0M0R0 esophageal cancer. Ann Surg 2010;252:744–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Hagen P, Wijnhoven BP, Nafteux P, et al. Recurrence pattern in patients with a pathologically complete response after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and surgery for oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg 2013;100:267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizk NP, Venkatraman E, Bains MS, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system does not accurately predict survival in patients receiving multimodality therapy for esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xi M, Hallemeier CL, Merrell KW, et al. Recurrence Risk Stratification After Preoperative Chemoradiation of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Luc G, Gronnier C, Lebreton G, et al. Predictive Factors of Recurrence in Patients with Pathological Complete Response After Esophagectomy Following Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Esophageal Cancer: A Multicenter Study. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22 Suppl 3:S1357–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chao YK, Chan SC, Liu YH, et al. Pretreatment T3–4 stage is an adverse prognostic factor in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma who achieve pathological complete response following preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Ann Surg 2009;249:392–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizk NP, Seshan VE, Bains MS, et al. Prognostic factors after combined modality treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:1117–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fine JP GR. A proportional haxards model for the subdistribution of competing risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1999;94:496–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku GY, Kriplani A, Janjigian YY, et al. Change in chemotherapy during concurrent radiation followed by surgery after a suboptimal positron emission tomography response to induction chemotherapy improves outcomes for locally advanced esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer 2016;122:2083–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim MK, Cho KJ, Park SI, et al. Initial stage affects survival even after complete pathologic remission is achieved in locally advanced esophageal cancer: analysis of 70 patients with pathologic major response after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;75:115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbetta A, Hsu M, Tan KS, et al. Definitive chemoradiotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery for stage II to III esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Koshy M, Greenwald BD, Hausner P, et al. Outcomes after trimodality therapy for esophageal cancer: the impact of histology on failure patterns. Am J Clin Oncol 2011;34:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oppedijk V, van der Gaast A, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Patterns of recurrence after surgery alone versus preoperative chemoradiotherapy and surgery in the CROSS trials. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:385–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fields RC, Strong VE, Gonen M, et al. Recurrence and survival after pathologic complete response to preoperative therapy followed by surgery for gastric or gastrooesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 2011;104:1840–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1 – Study cohort, with excluded patients.

Supplemental Figure 2 – Overall survival (OS) by histology. OS in patients with adenocarcinoma (adeno) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) does not differ significantly and approaches 60% at 5 years.

Supplemental Figure 3 – Disease-free survival (DFS) by histology. DFS in patients with adenocarcinoma (adeno) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) does not differ significantly and approaches 53% at 5 years.

Video Legend: Smita Sihag, MD, MPH