Abstract

Background

Gastric cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer death worldwide. Surgery is regarded as the best curative treatment option for gastric cancer; however, a high proportion of cases are diagnosed at advanced stages, when tumors are unresectable. In the present study, we evaluated the impact of pharmacological therapies in the survival of 168 patients diagnosed with metastatic gastric cancer from Costa Rica, a country with very high incidence and mortality rates for this malignancy.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 168 clinical records of patients diagnosed with metastatic gastric cancer from January 2009 to January 2012 at four major hospitals in Costa Rica. The Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of frequencies, while the ANOVA test was used for comparison of quantitative variables. OS and PFS analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The Log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Univariate and multivariate COX regression analyses were used to calculate the crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI).

Results

After a median follow-up of 46.5 months, the median survival difference between the two groups (pharmacological therapy vs. supportive care) was 5.6 months for PFS and 8.3 months for OS. Patients receiving triple therapy had 69% higher chance of progression than those receiving double therapy (HR =1.69, 95% CI: 1.04–2.73). The probability of dying is 88% higher for the patients receiving triple therapy than for those using double therapy (HR =1.88, 95% CI: 1.15–3.11).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that pharmacological therapies significantly increase the PFS and OS of those patients with metastatic gastric cancer in Costa Rica. The greatest benefit in terms of survival is observed with the use of duplets in comparison with the triplets in these patients.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasm, drug therapy, survival, prognosis, Latin America

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most diagnosed neoplasm worldwide (1). In Costa Rica, gastric cancer is among the most prevalent neoplasms and one of the leading causes of cancer death in men and women (1-6). Even though surgery remains as the best curative option for gastric cancer, only 30% to 60% of the patients undergo surgical resection given the high proportion of cases with tumors in advanced or metastatic stages at diagnosis. In these cases, pharmacological therapy becomes the most suitable, or even the only, treatment option (7,8). Despite the survival benefits that have been observed with combination therapies, many of the patients do not respond to existing treatment regimens. Given the scarcity of therapeutic opportunities and the lack of response to the existing ones, the prognosis of advanced gastric cancer remains very poor (7,9,10).

This study evaluated the impact in progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of pharmacological therapies used in Costa Rica for the treatment of metastatic gastric cancer. Our results demonstrate that therapies significantly increase the PFS and OS of those patients with metastatic gastric cancer.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical records of all consecutive patients diagnosed with metastatic gastric cancer from January 2009 to January 2012 (168 patients). These medical records were retrieved from all the hospitals in Costa Rica with Clinical Oncology Service and Oncology Pharmacy at the time of the study (Hospital San Juan de Dios, Hospital Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia, Hospital Max Peralta and Hospital México). Patients were followed-up until January 2016 (date of censorship), or at the time when the patients died. Baseline clinical and tumor characteristics, as well as treatment data were all manually reviewed from the clinical records. All cases were reclassified according to the TNM criteria as described by AJCC 7th edition. Patient performance status was evaluated according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) criteria. The study was approved by the Ethical Scientific Committee of the University of Costa Rica (# 817-B2-371) and the Institutional Scientific Ethics Committee of the Caja Costarricense Seguro Social (CCSS) (R013-SABI-00048).

The treatments used included of one of the following: capecitabine only (2,000 mg/m2/day from day 1 to day 14 every 21 days) [CAP monotherapy], combination of a fluoropyrimidine (5FU 400 mg/m2 day 1 followed by 2,400 mg/m2/48 hours infusion every 15 days and leucovorin 400 mg/m2 day 1, or capecitabine 2,000 mg/m2/day from day 1 to 14 every 21 days) and oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2 every 15 days or 130 mg/m2 every 21 days) or cisplatin (50 mg/m2 every 15 days) (FOLFOX or CAPEOX regimens). Other selected treatments were the combination of epirubicin (50 mg/m2 day 1), cisplatin (60 mg/m2 day 1) and capecitabine (1,250 mg/m2 daily for 21 days) every 3 weeks (EPX regimen); as well as paclitaxel (135 mg/m2 day 1) with cisplatin (75 mg/m2 day 2 every 21 days), or paclitaxel only (80 mg/m2 day 1 weekly).

All patients were followed up at three-month intervals during the first two years, then at six-month intervals for three years, and yearly thereafter. Follow-up consisted of physical examination and computer tomography or ultrasound images as clinically indicated.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as percentages and continuous variables as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on their parametric or non-parametric distribution, respectively. The Chi-square test or Fisher´s exact test was used for comparison of frequencies, while the ANOVA test was used for comparison of quantitative variables. OS and PFS analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The Log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Univariate and multivariate COX regression analyses were used to calculate the crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with their 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Variables with P value less than 0.10 in univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis with the backward stepwise technique.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 21.0 for Mac (Chicago, Illinois, USA). All statistical tests were two-tailed. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Median follow-up time for the 168 metastatic patients was 46.5 months (IQR, 13.3–60.7 months). Demographic and clinical-pathological parameters are summarized in Table 1. Only 40 of the cases (23.8%) underwent surgical resection of the primary tumors and these lesions were mostly located in the gastric body.

Table 1. Demographic and clinic-pathological parameters of the metastatic patients included in the study.

| Variable | Number (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 61±14.8 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 97 (57.7) |

| Female | 71 (42.3) |

| Borrmann classification | |

| 1 | 6 (3.6) |

| 2 | 18 (10.7) |

| 3 | 82 (48.8) |

| 4 | 27 (16.1) |

| Unknown | 35 (20.8) |

| Laurent’s classification | |

| Intestinal | 147 (87.5) |

| Diffuse | 21 (12.5) |

| Tumor location | |

| Antro-pylorus | 36 (21.4) |

| Gastric body | 97 (57.7) |

| Fundus | 33 (19.6) |

| Not reported | 2 (1.2) |

| Performance status | |

| 0 | 35 (20.8) |

| 1 | 85 (50.6) |

| 2 | 26 (15.5) |

| 3 | 14 (8.3) |

| 4 | 8 (4.8) |

Of the total number of metastatic patients, 88 received pharmacological treatment, 17 went through a second-line treatment and only one was subjected to third-line treatment. The median survival difference between the two groups (pharmacological therapy vs. supportive care) was 5.6 months for PFS and 8.3 months for OS (Table 2).

Table 2. Impact of pharmacological therapy in progression-free survival and median overall survival of metastatic patients.

| Variables | n | Median PFS (months) | Median OS (months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | P | Median (95% CI) | P | |||

| Drug treatment | ||||||

| No treatment+ | 80 | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) | 2.5 (2.1–3.0) | |||

| Treatment | 88 | 8.1 (5.9–10.3) | <0.001 | 10.8 (7.8–13.7) | <0.001 | |

| Number of drugs used | ||||||

| Monotherapy* | 4 | 2.9 (2.9–3.0) | 2.9 (1.9–3.7) | |||

| Double therapy+ | 46 | 10.5 (3.5–17.5) | 13 (7.3–18.68) | |||

| Triple therapy | 38 | 6.3 (3.0–9.5) | 0.013 | 7.2 (3.2–11.24) | 0.012 | |

| Therapy type | ||||||

| FP + Pt+ | 46 | 10.5 (3.5–17.5) | 13.0 (7.3–18.7) | |||

| Epi + Pt + FP | 36 | 6.3 (2.8–9.7) | 0.035 | 7.2 (3.2–11.3) | 0.006 | |

*, monotherapy is not included in the analysis of drug numbers; +, reference groups: no treatment, FP + Pt. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

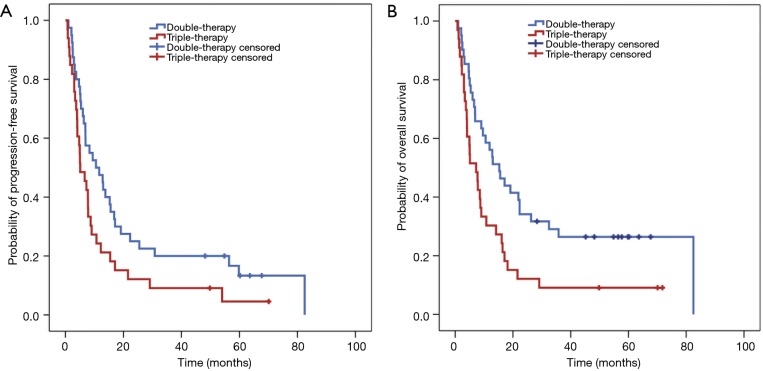

We performed further analyses taking into the number and the type of drugs that had been used to treat the metastatic patients. According to these, both parameters have an impact in PFS and OS. More specifically, patients receiving triple therapy had 69% higher chance of progression than those receiving double therapy (HR =1.69, 95% CI: 1.04–2.73) (Table 2) (Figure 1A). Also, the probability of dying is 88% higher for the patients receiving triple therapy than for those using double therapy (HR =1.88, 95% CI: 1.15–3.11) (Table 2) (Figure 1B). Combination of platinum (Pt) with fluoropyrimidines (FPs) was used as a double therapy, whereas triple therapy consisted of epirubicin (Epi), Pt and FPs (i.e., EOX, FEC). We found that patients under EOX or ECF regimens had 32% more likelihood to progress (HR =1.32, 95% CI: 1.03–1.69) and 42% more probability to die (HR =1.42, 95% CI: 1.10–1.83) than those receiving Pt + FPs.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival (PFS) (A) and overall survival (OS) (B) according to the use of double or triple therapy in patients with metastatic disease.

According to the clinical records, liver and peritoneum were the two most frequent metastatic sites in this set of gastric cancer patients (Table 3). Also, many of the patients presented more than one metastatic lesion at the time of diagnosis. We determined whether the number of metastatic lesions could have an impact in the survival of the patients. We, however, found no impact in PFS or OS according to the number of metastasis (P=0.589 and P=0.466, respectively).

Table 3. Anatomical sites harboring metastatic lesions in the studied patients.

| Anatomical site | Metastasis number (%) |

|---|---|

| Liver | 77 (45.8) |

| Peritoneum | 47 (27.9) |

| Non-regional lymph nodes | 10 (5.9) |

| Ovary | 9 (5.4) |

| Lung | 6 (3.6) |

| Pleura | 3 (1.8) |

| Spleen | 3 (1.8) |

| CNS | 2 (1.2) |

| Others | 12 (7.1) |

Finally, we assessed the impact of the patient's functional status (ECOG) on survival. For this analysis, we dichotomized the patients in ECOG of 0–1 and ECOG equal to or greater than 2. We found that patients with 0-1 ECOG at the time of diagnosis, have longer PFS and OS than those with an ECOG equal to or greater than 2 (Table 4). More specifically, patients with ECOG 0–1 are 36% less likely to show disease progression than those with ECOG 2–4 (HR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.45–0.92); and 40% more likely to survive than those with ECOG 2–4 at the time of diagnosis (HR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.42–0.87).

Table 4. Progression-free and overall survival of the patients with metastatic disease according to ECOG.

| ECOG | n | PFS (months) | OS (months) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (95% CI) | P | Median (95% CI) | P | |||

| 0–1 | 85 | 6.6 (5.4–7.8) | – | 7.4 (5.7–9.0) | – | |

| 2–4 | 47 | 2.9 (2.6–3.2) | 0.017 | 2.9 (2.6–3.2) | 0.006 | |

| ND | 36 | – | – | – | – | |

Reference group: ECOG 0–1. ND, no data available. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

Discussion

Despite the gradual decline in gastric cancer incidence and mortality rates in recent decades, this disease remains as the second leading cause of cancer death in Costa Rica (2,6,11). High mortality due to gastric cancer is mainly attributed to the fact that many cases are diagnosed in advanced stages, when the probability of curing the disease is very limited. In these cases, pharmacological therapy becomes the main treatment option (11-14). So far, no studies had been conducted in Costa Rica to determine the impact of the pharmacological therapy on the survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic evaluation of this kind in Latin America and shows that pharmacological therapy does have an impact in both PFS and OS of gastric cancer patients with metastatic disease.

According to this study, chemotherapy increases by several months both PFS and OS of gastric cancer patients harboring metastatic lesions. This is in line with international guidelines, with recommend the administration of palliative drug therapy for these patients since this may translate into increases in OS ranging from 8.6 to 11.1 months (7,13-15).

A particularly interesting observation in our study is that patients with metastatic disease obtain greater benefit in terms of survival with the use of doublet than with triplet drug regimen. The use of triplets in metastatic patients is controversial, due to the increase in adverse effects associated with these combinations even when some studies have shown that these increase the survival of patients (7,13-18). A meta-analysis for advanced gastric and gastroesophageal cancer found that triple regimen confers higher OS, PFS and higher response rates than double therapy, but only when taxane is included in the triplet, in addition to platinum and fluoropyrimidine. According to this meta-analysis, the addition of an anthracycline to a doublet did not meet statistical significance for OS. The survival benefit of the triplet with anthracycline, becomes comparable to the one of patients under a dual therapy regimen (16). Dual therapy employed in Costa Rica, at least for the time lapse when this study was conducted, generally included platinum and fluoropyrimidine, whereas triple regimens all included anthracycline, platinum, and fluoropyrimidine. All these observations, taken together, suggest that the use of triplets does not necessarily translate into a greater survival benefit, compared to doublets; which could be influenced by many factors, both biological and clinicopathological, as well as the types of chemotherapeutic agents being combined.

The functional status of the patient plays a pivotal role for making decisions about the clinical management of the cancer patients. In this study, stage IV patients with a functional status (ECOG) between 0–1 had greater PFS and OS compared to patients with functional status equal to or greater than 2. These results agree with those reported in previous studies (7,17-19). According to several of these reports, the benefits attributed to the pharmacological therapy in patients with metastatic stage and ECOG greater than 3 do not overcome the adverse effects that are typical of the medication (7,17,18).

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the use of chemotherapy extends the survival of patients with gastric metastatic cancer, which could be especially associated with the use of doublets. However, according to the results of this study, it is necessary to adequately choose the therapy to be used, to provide a survival benefit, but without generating significant toxicities.

Acknowledgements

None.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the Ethical Scientific Committee of the University of Costa Rica (# 817-B2-371) and the Institutional Scientific Ethics Committee of the Caja Costarricense Seguro Social (CCSS) (R013-SABI-00048).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359-86. 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social. Incidencia y mortalidad del Cáncer en Costa Rica. Costa Rica: 2015. Available online: http://www.ccss.sa.cr/cancer?v=41, accessed 28 April 2018.

- 3.Sierra R, Barrantes R. Epidemiología y Ecología del cáncer gástrico en Costa Rica. Bol of Sanit Panam 1983;95:495-506. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sierra MS, Cueva P, Bravo LE, et al. Stomach cancer burden in Central and South America. Cancer Epidemiol 2016;44 Suppl 1;S62-73. 10.1016/j.canep.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society. Available online: http://cancer.org, accessed 10 June 2018.

- 6.Ministerio Salud D. Memoria Institucional Ministerio de Salud, Costa Rica. Costa Rica, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN Clinical Guidelines for Gastric Cancer. Version 2 2018:1-84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elimova E, Wadhwa R, Charalampakis et al. Chapter 20: Gastric, Gastroesophageal Junction, and Esophageal Cancers. In: Kantarjian HM, Wolff RA. editors. The MD Anderson Manual of Medical Oncology. 3nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee J, Lim T, Uhm JE, et al. Prognostic model to predict survival following first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol 2007;18:886-91. 10.1093/annonc/mdl501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bang YJ, Cutsem EV, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:687-97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim S, Muhs BE, Marcus SG, et al. Results following resection for stage IV gastric cancer; are better outcomes observed in selected patient subgroups? J Surg Oncol 2007;95:118-22. 10.1002/jso.20328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med 2001;345:725-30. 10.1056/NEJMoa010187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuo CY, Chao Y, Li CH. Update on treatment of gastric cancer. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association 2014;77:345-53. 10.1016/j.jcma.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okines A, Verheij M, Allum W, et al. Gastric cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010;21:v50-4. 10.1093/annonc/mdq164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izuishi K, Mori H. J Recent Strategies for Treating Stage IV Gastric Cancer: Roles of Palliative Gastrectomy, Chemotherapy, and Radiotherapy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2016;25:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohammad NH, Veer E, Ngai L, et al. Optimal first-line chemotherapeutic treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic esophagogastric carcinoma: triplet versus doublet chemotherapy: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2015;34:429-41. 10.1007/s10555-015-9576-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berger AK, Zschaebitz S, Komander C, et al. Palliative chemotherapy for gastroesophageal cancer in old and very old patients: A retrospective cohort study at the National Center for Tumor Diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:4911-8. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bittoni A, Del Prete M, Scartozzi M, et al. Three drugs vs two drugs first-line chemotherapy regimen in advanced gastric cancer patients: a retrospective analysis. Springerplus 2015;4:743. 10.1186/s40064-015-1545-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohri Y, Tanaka K, Ohi M, et al. Identification of prognostic factors and surgical indications for metastatic gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 2014;14:409. 10.1186/1471-2407-14-409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]