Abstract

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (fHCC) is a rare primary liver cancer that affects young adults with no prior liver disease. fHCC-associated hyperammonemic encephalopathy (HAE) is an uncommon and life-threatening complication. Hyperammonemia has been reported in both typical and fHCC as a result of intrahepatic shunting, side effect from immunotherapy or chemotherapy, or as a paraneoplastic phenomenon. We present a case of a 32-year-old woman with recurrent metastatic fHCC who developed HAE in the setting of steroid administration. Her hyperammonemia was exacerbated by steroid-induced protein catabolism. She was treated with ammonia scavenging medications, a low protein diet, and was placed on chronic ammonia scavenger therapy while undergoing chemotherapy. In this case report, we discuss the proposed mechanisms of HAE, and we review the literature regarding clinical presentation and treatment.

Keywords: Hyperammonemia, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (fHCC), ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, hyperammonemic encephalopathy (HAE)

Introduction

Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (fHCC) is a rare primary liver cancer that affects young adults, most commonly between age 10 to 35 (1), with no underlying liver disease. The age-adjusted incidence is 0.02 cases per 100,000 individuals (2), about 100 times lower than hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Patients with fHCC usually present with abdominal pain, nausea, weight loss, and the physical exam may reveal a palpable abdominal mass (1). Diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, imaging, and histologic studies. Serum alpha fetoprotein levels are usually normal. Surgery is the only curative option for patients presenting with resectable disease. No consensus exists regarding the optimal treatment with a chemotherapy regimen of unresectable disease. We report hyperammonemic encephalopathy (HAE) as an unusual presentation of fHCC is, and to our knowledge, only 10 other cases have been reported in the literature (3-12).

Case presentation

A 32-year-old woman with recurrent metastatic fHCC status post chemoembolization, surgical resection, and treatment with multiple chemotherapy agents, presented with progressive confusion over 1 week. She had recently received nivolumab, but treatment was discontinued due to disease progression and what was thought to be possible nivolumab-induced autoimmune hepatitis. She was admitted to a local hospital with mental status changes and was treated with antibiotics for possible infection, steroids and levetiracetam for possible seizure, and lactulose and rifaximin for possible hepatic encephalopathy secondary to a presumptive diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Given her lack of improvement, she was transferred to a tertiary care hospital for further management. Early during the course of her work-up a liver biopsy failed to show any evidence of autoimmune hepatitis.

On exam, patient appeared cushingoid, was unresponsive to painful stimuli, and had clonus in bilateral lower extremities. She was intubated soon after admission. Her initial laboratory investigation was notable for an elevated ammonia level of 300 µmol/L (normal range: <30 µmol/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 67 U/L (normal range: 8–43 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 237 U/L (normal range: 7–45 U/L), normal alkaline phosphatase, normal total and direct bilirubin, and normal prothrombin time. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head were normal. Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed diffuse slowing consistent with severe encephalopathy.

Metabolic laboratory analysis showed a severe elevation of glutamine (1,214 nmol/mL, normal range: 371–957 nmol/mL) and a decrease of essential amino acids including all branched-chain amino acids, tryptophan, and phenylalanine indicating severe catabolic stress (13). Urine orotic acid was not elevated, and arginine and citrulline were not significantly decreased thereby less consistent with a primary urea cycle disorder. Nonetheless, the patient underwent genetic testing of 44 genes associated with inborn errors of metabolism that could feature hyperammonemia. Ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) gene analysis showed no variants, but she was found to be a carrier for a single heterozygous pathogenic variant in the gene for carnitine palmitoyltransferase 2 (CPT2). CPT2 deficiency is an autosomal recessive disease, and a second variant was not found. Also, CPT2 deficiency does did not fit with her symptoms (14). Treatment was started with intravenous sodium phenylacetate and sodium benzoate at a combined dose of 5.5 g/m2 given over a 2-hour bolus and then continued as a daily infusion. She was infused with arginine and dextrose containing fluid to reduce catabolism. Her ammonia level decreased to 50 µmol/L, and she was extubated after 2 days of initiating ammonia scavenging therapy. She was transitioned to oral glycerol phenylbutyrate 2.75 g three times a day and L-citrulline 3,000 mg four times a day. She was also advised to maintain a low protein (60 g daily) diet.

Four months later, she was hospitalized again for acute encephalopathy after receiving rovalpituzumab tesirine, a monoclonal antibody against delta like protein 3 (DLL3), and dexamethasone 8 mg twice daily for three days. Her initial ammonia level was 150 µmol/L. Catabolic stress was observed with decrease in essential amino acids but normal glutamine, arginine, and citrulline. She was treated with IV sodium phenylacetate and sodium benzoate, arginine, and dextrose with improvement of her mental status after 2 doses. Each dose was run over 24 hours. She was also placed on a strict low protein diet (60 g daily). Interestingly, her ammonia levels fluctuated between 150 and 250 µmol/L and did not correlate with her mental status. In fact, she was at her neurologic baseline with an ammonia level of 218 µmol/L when she was discharged from the hospital. When she presented for follow-up, the decision was made to proceed with another dose of rovalpituzumab tesirine but limit the exposure to steroids to decrease protein catabolism.

Discussion

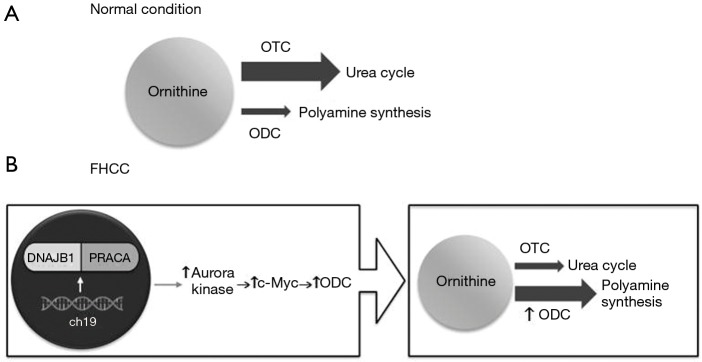

Hyperammonemia is usually seen in the setting of liver failure, but it can be secondary to underlying malignancy, chemotherapy, or an inborn error of metabolism. Ammonia is a byproduct of protein metabolism, and it is converted into urea and excreted by the kidneys (Figure 1). Ammonia is a neurotoxin; at high levels, it crosses the blood-brain barrier and is conjugated with glutamate into glutamine, which acts as an osmolyte, causing cerebral edema (15,16). Clinical features of elevated ammonia levels include changes in sleep-wake cycle, irritability, confusion, and if untreated can lead to seizures, coma, and eventually death (17). HAE is a rare complication of cancer or cancer treatment. We found 10 other cases of HAE in fHCC patients (Table 1), with an average age of 22 years and 60% were women. HAE can be seen as an initial presentation or late in the disease course of fHCC.

Figure 1.

Urea cycle. OTC, ornithine transcarbamylase.

Table 1. Reported patients with hyperammonemic encephalopathy associated with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Author | Age, gender | Presentation | Initial ammonia level (reference range ≤30 µmol/L) | Metabolic profile similar to OTC deficiency | Hyperammonemia treatment | Chemotherapy regimen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surjan et al. 2017 (12) | 31, man | Lethargy and confusion one week after diagnostic laparotomy and liver biopsy | 204 µmol/L | Yes | Neomycin, lactulose, and L-ornithine-L-aspartate, then hemodialysis, then sodium benzoate and arginine | Sorafenib, gemcitabine, oxaliplatin |

| Chapuy et al. 2016 (7) | 31, man | Day 3 after chemotherapy, presented with somnolence and tremor | 300 µmol/L | Yes | Sodium benzoate, citrulline | Gemcitabine, oxaliplatin |

| Alsina et al. 2016 (3) | 23, woman | Initial presentation with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain then coma | 257 µmol/L (peak ammonia level) | Not reported | Lactulose, rifaximin, liver transplant | Treated with emergency liver transplant; no chemotherapy |

| Sulaiman et al. 2015 (11) | 20, woman | History of previously treated fHCC, presented with confusion, agitation, and vomiting | 281 µmol/L | Yes | Sodium phenylbutyrate, sodium benzoate, arginine | Sorafenib |

| Bender et al. 2015 (4) | 19, woman | Metastatic fHCC, transferred to palliative care, complicated by recurrent hyperammonemic episodes with neurologic symptoms | 264 µmol/L (peak ammonia level) | Resembled impaired urea cycle, but urine orotic acid level was not checked | Sodium phenyl butyrate | Previously treated with sorafenib, bevacizumab, erlotinib, platinum, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine |

| Shinde et al. 2014 (10) | 21, man | Metastatic fHCC, presented with nausea and progressive confusion | 65 µmol/L | Yes | Arginine | Sunitinib |

| Berger et al. 2012 (5) | 22, woman | Initial presentation with altered mental status, ascites, then coma | 254 µmol/L | Not reported | None | Bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin |

| Hashash et al. 2012 (8) | 18, woman | Initial presentation with nausea, progressive confusion | 342 µmol/L | Yes | Lactulose, rifaximin, hemodialysis, sodium phenylacetate and sodium benzoate, arginine | Imetelstat |

| Chan et al. 2008 (6) | 22, woman | Initial presentation with abdominal pain, weight loss, progressive cognitive decline | 280 µmol/L | Yes | Lactulose, arginine | Not reported |

| Sethi et al. 2009 (9) | 18, man | Initial presentation with slowing of movements and urinary incontinence | 137 µmol/L | Not reported | None | Sorafenib |

OTC, ornithine transcarbamylase; fHCC, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma.

Pathophysiology

There are four proposed mechanism of HAE in fHCC patients. (I) Intrahepatic shunting of ammonia away from cancer cells can cause serum ammonia elevation (5,9). (II) The initiation of chemotherapy can cause increased cell breakdown, leading to excess nitrogen load which oversaturates the liver’s nitrogen clearance capacity (6). (III) Cancer cells under treatment were shown to have decreased expression of the OTC gene, which encodes an enzyme necessary for ammonia metabolism into urea (18). (IV) A paraneoplastic process that disrupts the urea cycle, causing decreased ammonia clearance (4,7). Several HAE cases previously reported occurred prior to starting chemotherapy (3,5,6,8,12) and ammonia levels were persistently elevated without chemotherapy (4,7,12). Seven of the 10 cases had a metabolic profile similar to OTC deficiency, suggesting that the most likely mechanism is a paraneoplastic phenomenon associated with fHCC.

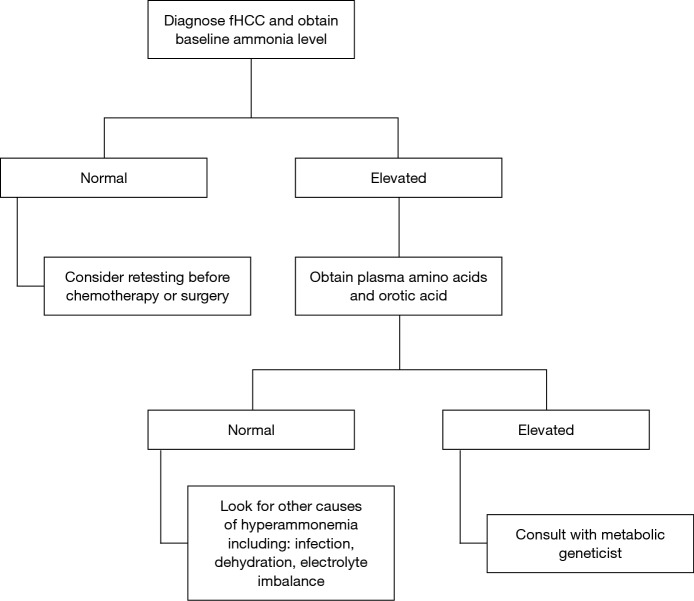

Surjan et al. proposed a pathway (Figure 2) that explains the acquired urea cycle disorder in fHCC patients. fHCC is characterized by a heterozygous deletion on chromosome 19 that encoded a functional chimeric transcript DNAJB1-PRKACA which is found in up to 80% of cases (12,19,20), although this was not found in our patient. DNAJB1 is a heat shock protein, and PRKACA is a catalytic subunit of protein kinase A. This fusion protein increases the expression of Aurora kinase A, which then upregulates c-Myc expression. C-Myc is an oncogene, and one of its targets is ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), resulting in the overexpression of ODC. ODC catalyzes the decarboxylation of ornithine in polyamine synthesis. Therefore, with increased levels of ODC, ornithine preferentially enters the polyamine synthesis pathway leading to substrate deprivation of the urea cycle. This inhibits ornithine transcarbamylase activity, leading to decreased ammonia clearance.

Figure 2.

Proposed mechanism of urea cycle dysfunction in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (fHCC). Under normal condition (A), OTC activity is higher than ODC, so ornithine enters the urea cycle. In fHCC (B), mutation in chromosome 19 led to a chimeric protein DNAJB1-PRACA that leads to increased ODC activity, resulting in an increased utilization of ornithine for polyamine synthesis and a decreased urea cycle function. ch19, chromosome 19; DNAJB1, DnaJ Heat Shock Protein Family (Hsp40) Member B1; PRKACA, Protein Kinase CAMP-Activated Catalytic Subunit Alpha; c-Myc, myelocytomatosis oncogene; ODC, ornithine decarboxylase; OTC, ornithine transcarbamylase.

In our patient, based on her metabolic laboratory analysis, we postulated that her hyperammonemia was secondary to severe catabolic stress from steroid administration with chemotherapy leading to nitrogen overload. Her urine orotic acid was not elevated, and arginine and citrulline were not significantly decreased, arguing against a primary urea cycle dysfunction at the level of ornithine transcarbamylase. Additionally, this observation of a consistently elevated ammonia and baseline mental status would be consistent with chronic hyperammonemia. This argues that she likely had hyperammonemia prior to her coma presentation and that she was somewhat tolerant to this elevation.

Diagnosis and suggested treatment of HAE in fHCC

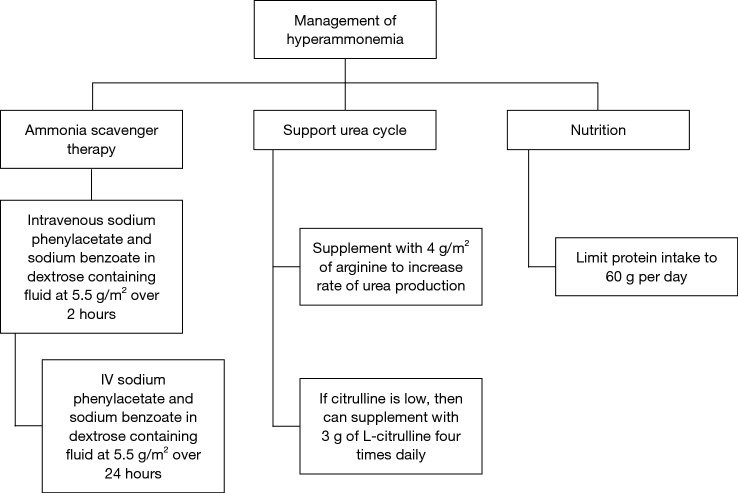

The clinical features of hyperammonemia can be subtle. We suggest checking a baseline ammonia level in all patients who are newly diagnosed with fHCC, and if it is high, obtain urine organic acids and plasma amino acids. Individuals with decreased OTC activity tend to have a low citrulline and high glutamine levels in the blood, and an elevated orotic acid level in the urine (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diagnostic algorithm for hyperammonemic encephalopathy in the setting of fHCC. fHCC, fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma.

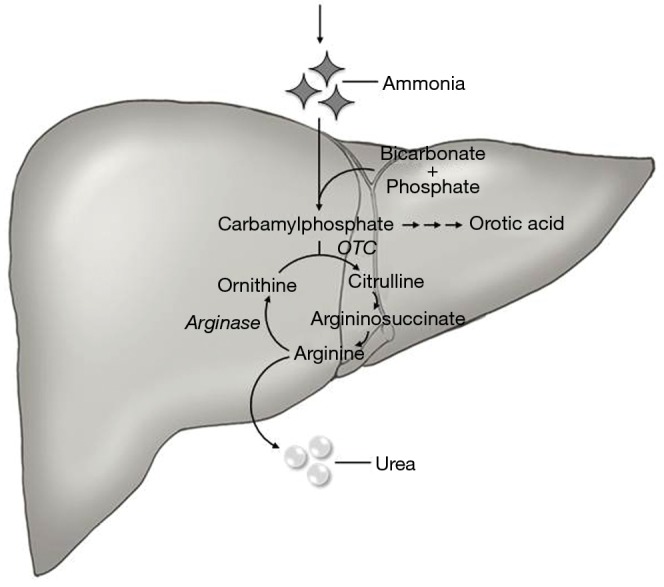

For the acute management of hyperammonemia, the fastest method to lower ammonia level is hemodialysis (21). Ammonia scavengers are often used. We recommend starting with IV sodium phenylacetate and sodium benzoate administered at a dose of 5.5 g/m2 over a 2-hour period and an additional 5.5 g/m2 over 24 hours (22). This should be infused with arginine 2–6 g/m2. Arginine is used to generate urea cycle intermediates. Citrulline can also be given if the level is low. Ammonia scavengers should be continued during chemotherapy, and there are oral formulations, such as sodium phenylbutyrate and glycerol phenylbutyrate (23) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Suggested management algorithm for hyperammonemic encephalopathy in fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (fHCC). Hemodialysis should be considered if emergent.

Conclusions

HAE can be an initial presentation or a late complication in patients with fHCC. Hyperammonemia can be life threatening, so treatment should be initiated promptly to prevent permanent neurologic damage. There are several proposed mechanisms for decreased nitrogen excretion. In fHCC, hyperammonemia is likely secondary to a paraneoplastic phenomenon involving the overexpression of an enzyme, ODC, which competes with OTC in the urea cycle, resulting in a functional OTC deficiency. In addition, any event that causes increased cell breakdown and catabolism can overwhelm the already impaired urea cycle. Treatment is focused on lowering ammonia level with ammonia scavengers and/or hemodialysis.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Lafaro KJ, Pawlik TM. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma: current clinical perspectives. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2015;2:151-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Is fibrolamellar carcinoma different from hepatocellular carcinoma? A US population-based study. Hepatology 2004;39:798-803. 10.1002/hep.20096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alsina AE, Franco E, Nakshabandi A, et al. Successful Liver Transplantation for Hyperammonemic Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma. ACG Case Rep J 2016;3:e106. 10.14309/crj.2016.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bender HU, Staudigl M, Schmid I, et al. Treatment of Paraneoplastic Hyperammonemia in Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma With Oral Sodium Phenylbutyrate. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:e8-10. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger C, Dimant P, Hermida L, et al. Hyperammonemic encephalopathy and fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicina (B Aires) 2012;72:425-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan JS, Harding CO, Blanke CD. Postchemotherapy hyperammonemic encephalopathy emulating ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC) deficiency. South Med J 2008;101:543-5. 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31816bf5cc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapuy CI, Sahai I, Sharma R, et al. Hyperammonemic Encephalopathy Associated With Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Case Report, Literature Review, and Proposed Treatment Algorithm. Oncologist 2016;21:514-20. 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashash JG, Thudi K, Malik SM. An 18-year-old woman with a 15-cm liver mass and an ammonia level of 342. Gastroenterology 2012;143:1157-402. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sethi S, Tageja N, Dave M, et al. Hyperammonemic Encephalopathy: A Rare Presentation of Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am J Med Sci 2009;338:522-4. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181bccfb4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shinde SS, Sharma P, Davis MP. Acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy in a non-cirrhotic patient with hepatocellular carcinoma reversed by arginine therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:e5-7. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sulaiman RA, Geberhiwot T. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma mimicking ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. JIMD Rep 2014;16:47-50. 10.1007/8904_2014_318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surjan RC, Dos Santos ES, Basseres T, et al. A Proposed Physiopathological Pathway to Hyperammonemic Encephalopathy in a Non-Cirrhotic Patient with Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma without Ornithine Transcarbamylase (OTC) Mutation. Am J Case Rep 2017;18:234-41. 10.12659/AJCR.901682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scriver CR, Blau N, Duran M, et al. Physician’s Guide to the Laboratory Diagnosis of Metabolic Diseases. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longo N, Amat di San Filippo C, Pasquali M. Disorders of carnitine transport and the carnitine cycle. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2006;142C:77-85. 10.1002/ajmg.c.30087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijdicks EFM. Hepatic Encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2017;376:186. 10.1056/NEJMc1614962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butterworth RF, Giguere JF, Michaud J, et al. Ammonia: key factor in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Pathol 1987;6:1-12. 10.1007/BF02833598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkes ND, Thomas GA, Jurewicz A, et al. Non-hepatic hyperammonaemia: an important, potentially reversible cause of encephalopathy. Postgrad Med J 2001;77:717-22. 10.1136/pmj.77.913.717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mavri-Damelin D, Eaton S, Damelin LH, et al. Ornithine transcarbamylase and arginase I deficiency are responsible for diminished urea cycle function in the human hepatoblastoma cell line HepG2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007;39:555-64. 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinh TA, Vitucci EC, Wauthier E, et al. Comprehensive analysis of The Cancer Genome Atlas reveals a unique gene and non-coding RNA signature of fibrolamellar carcinoma. Sci Rep 2017;7:44653. 10.1038/srep44653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riggle KM, Turnham R, Scott JD, et al. Fibrolamellar Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Mechanistic Distinction From Adult Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:1163-7. 10.1002/pbc.25970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lichter-Konecki U, Caldovic L, Morizono H, et al. Ornithine Transcarbamylase Deficiency. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al. editors. GeneReviews(R). Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batshaw ML, MacArthur RB, Tuchman M. Alternative pathway therapy for urea cycle disorders: twenty years later. J Pediatr 2001;138:S46-54; discussion S54-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Misel ML, Gish RG, Patton H, et al. Sodium benzoate for treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2013;9:219-27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]