Significance

Roots produce hundreds to thousands of small molecules with unknown functions. We targeted the apocarotenoid pathway, which has been linked to numerous developmental processes in Arabidopsis, for a sensitized chemical genetic screen to identify regulators of root development. β-Cyclocitral, a small molecule derived from β-carotene, was identified as a regulator of root stem cell behavior in Arabidopsis as well as in rice and tomato. β-Cyclocitral promotes root stem cell divisions to enhance root growth and branching. In rice, β-cyclocitral enhanced both root and shoot growth during salt stress, which has important implications for agriculture.

Keywords: carotenoid, plant hormone, abiotic stress, meristem, lateral root emergence

Abstract

Natural compounds capable of increasing root depth and branching are desirable tools for enhancing stress tolerance in crops. We devised a sensitized screen to identify natural metabolites capable of regulating root traits in Arabidopsis. β-Cyclocitral, an endogenous root compound, was found to promote cell divisions in root meristems and stimulate lateral root branching. β-Cyclocitral rescued meristematic cell divisions in ccd1ccd4 biosynthesis mutants, and β-cyclocitral–driven root growth was found to be independent of auxin, brassinosteroid, and reactive oxygen species signaling pathways. β-Cyclocitral had a conserved effect on root growth in tomato and rice and generated significantly more compact crown root systems in rice. Moreover, β-cyclocitral treatment enhanced plant vigor in rice plants exposed to salt-contaminated soil. These results indicate that β-cyclocitral is a broadly effective root growth promoter in both monocots and eudicots and could be a valuable tool to enhance crop vigor under environmental stress.

A rapidly increasing world population, coinciding with changes in climate, creates a need for new methods to stabilize and improve crop productivity under harsh environmental conditions. Exogenously applied metabolites and phytohormones, such as auxin, cytokinin, and ethylene, have had profound impacts on agriculture by selectively killing weeds, promoting shoot growth, and optimizing fruit ripening (1–5). Root traits such as growth and branching are appealing targets for enhancing plant performance due to their essential role in nutrient and water uptake. In Arabidopsis, root development begins with the formation of a primary root during embryogenesis. Root branching is initiated by oscillations in gene expression at the tip of the primary root (6). These oscillations establish the future position of de novo roots called lateral roots (LRs) and are referred to as the “LR clock.” Stereotyped cell divisions promote LR primordia development by increasing cell number and generating all root cell types (7). In both primary roots and LRs, growth is maintained through cell divisions in the meristem and the subsequent elongation of daughter cells. Previously, inhibition of the carotenoid biosynthesis pathway was shown to reduce root growth and branching in Arabidopsis, suggesting that this pathway is important for LR development (8).

The carotenoid biosynthesis pathway is a rich source of metabolites, called apocarotenoids, several of which are known regulators of root development (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (9–11). Strigolactones and abscisic acid (ABA), which are apocarotenoid phytohormones, regulate root growth and LR branching, respectively (12–14). Previously, an inhibitor of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases (CCDs) called D15 was found to decrease LR branching through an ABA and strigolactone independent mechanism in Arabidopsis (8). This result suggested that one or more unidentified apocarotenoids could be positive regulators of LR development. Isolating these compounds through genetic means is difficult because each CCD has multiple substrates and produces a variety of different compounds, making it impossible to selectively eliminate a single apocarotenoid. Therefore, to identify natural compounds capable of promoting root growth and development, we leveraged D15 to characterize the effects of exogenously applied apocarotenoids on root traits in a sensitized background.

Results

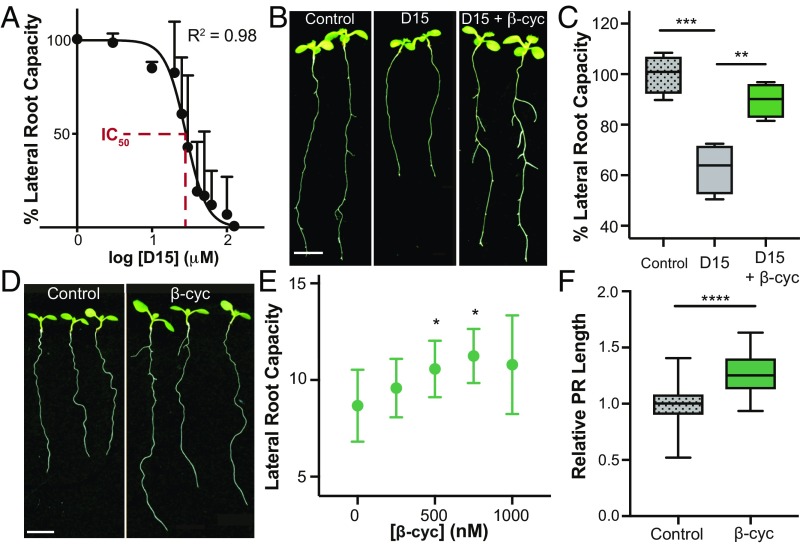

To identify apocarotenoids involved in LR development, we utilized a targeted chemical genetic approach to screen apocarotenoids for their ability to enhance root branching in the presence of D15. The maximum concentration of D15 tested (100 μM) decreased primary root length and completely inhibited LR capacity, the number of LRs that emerge after excision of the primary root apical meristem (8). By titrating D15 to 30 μM, the concentration at which it decreases LR emergence by 50% (IC50), we could measure changes in LR capacity with enhanced sensitivity (Fig. 1A). Most apocarotenoids tested, including ABA and GR24, a synthetic strigolactone analog, further decreased LR capacity when combined with D15 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Two apocarotenoids, dihydroactinidiolide (DHAD) and β-cyclocitral, were found to increase LR branching in the presence of D15. These compounds were previously found to trigger the reactive oxygen species (ROS) response and increase leaf tolerance to high light stress (15–17).

Fig. 1.

Identification of β-cyclocitral, a root growth promoter in Arabidopsis. (A) The LR capacity of D15-treated plants, normalized to control plants. The IC50 is highlighted in red. (B) Seedlings after treatment with 30 μM D15 and 25 μM volatile β-cyclocitral (β-cyc). (Scale bar, 5 mm.) (C) LR capacity of plants treated with 30 μM D15 and 25 μM volatile β-cyclocitral. (D) Arabidopsis seedlings treated directly with 750 nM β-cyclocitral. (Scale bar, 5 mm.) (E) Quantification of LR capacity of seedlings treated with increasing concentrations of β-cyclocitral. (F) Quantification of primary root length in β-cyclocitral–treated plants. *P = 0.05, **P = 0.01, ***P = 0.001, and ****P = 0.0001.

To further explore the effects of DHAD and β-cyclocitral on LR branching, we varied their concentrations in the presence of D15 at its IC50 concentration. We found that even the most effective concentration of DHAD increased root branching by only 14% (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). However, application of volatile β-cyclocitral had a much more dramatic effect, promoting root branching by nearly 40% (Fig. 1 B and C). Therefore, we focused on the mechanism of β-cyclocitral action. β-Cyclocitral has been identified endogenously in dozens of plant species, including tomato (18), rice (19), parsley (20), tea (21), grape (22), various trees (23, 24), and moss (25), indicating that its presence in plants is evolutionarily conserved. We further identified endogenous β-cyclocitral in Arabidopsis and rice roots at levels of 0.097 and 0.47 ng/mg dry weight, respectively, using HPLC-MS (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). A gene ontology term enrichment analysis of previously published data in Arabidopsis revealed that genes up-regulated by β-cyclocitral are important for the immune system, metabolite catabolism, and abiotic stress responses, indicating that β-cyclocitral may play a number of roles in growth and development (SI Appendix, Table S1) (15).

To determine the effects of exogenous β-cyclocitral application in the absence of D15, we examined changes in root architecture upon treatment with β-cyclocitral alone. This treatment enhanced primary root length and LR branching by 30% compared with control treatment (Fig. 1 D–F). The maximum efficacy of exogenous β-cyclocitral treatment occurred at a concentration of 750 nM, which is comparable to the levels at which exogenous ABA and strigolactones confer phenotypic changes (13). Apocarotenoids with nearly identical chemical structures, such as dimethyl-β-cyclocitral and β-ionone, did not increase root branching (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2). These results suggest that β-cyclocitral is the active molecule or is a unique precursor to the active metabolite regulating LR branching (26).

To understand how β-cyclocitral promotes LR branching, we characterized its effect on LR development in the presence and absence of D15. Its ability to increase LR capacity suggests that it either increases initiation of new LRs or induces LR outgrowth. Since initiation is preceded by the LR clock, we monitored pDR5:LUC, a marker line that gives a readout of LR clock oscillations, after D15 and β-cyclocitral treatment. The region of the root tip that experiences the peak luminescence oscillation intensity becomes competent to form LR primordia (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) (6). In D15-treated roots, the peak oscillation intensity was significantly lower compared with that of control roots (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). β-Cyclocitral did not affect the peak oscillation intensity, with or without D15, indicating that it does not increase initiation of LR primordia. To further test this, we examined the effect of β-cyclocitral on the formation of the first cell divisions in LR primordia. As expected, the IC50 concentration of D15 decreased the number of initiated LR primordia by ∼50% compared with untreated plants, as reported by the pWOX5:GFP marker line (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A) (27). Consistent with its inability to restore LR clock amplitude, β-cyclocitral did not increase the number of WOX5+ primordia in D15-treated plants. Additionally, it did not increase WOX5+ sites in the absence of D15. These results suggest that β-cyclocitral does not have a role in determining the number of initiated LR primordia and must instead promote LR branching by stimulating developmental stages that occur after initiation. To test this hypothesis, we used an EN7 marker line (pEN7:GAL4; UAS:H2A-GFP), which reports formation of the endodermis, an intermediate step before primordia emergence (28). β-Cyclocitral doubled the number of EN7+ primordia in D15-treated plants and increased EN7+ primordia by 16% compared with untreated plants (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B). Taken together, our results indicate that β-cyclocitral does not affect the total number of initiated LR primordia and that its effects are not directly related to the D15-induced phenotype. Instead, β-cyclocitral promotes cell divisions in LR primordia after initiation.

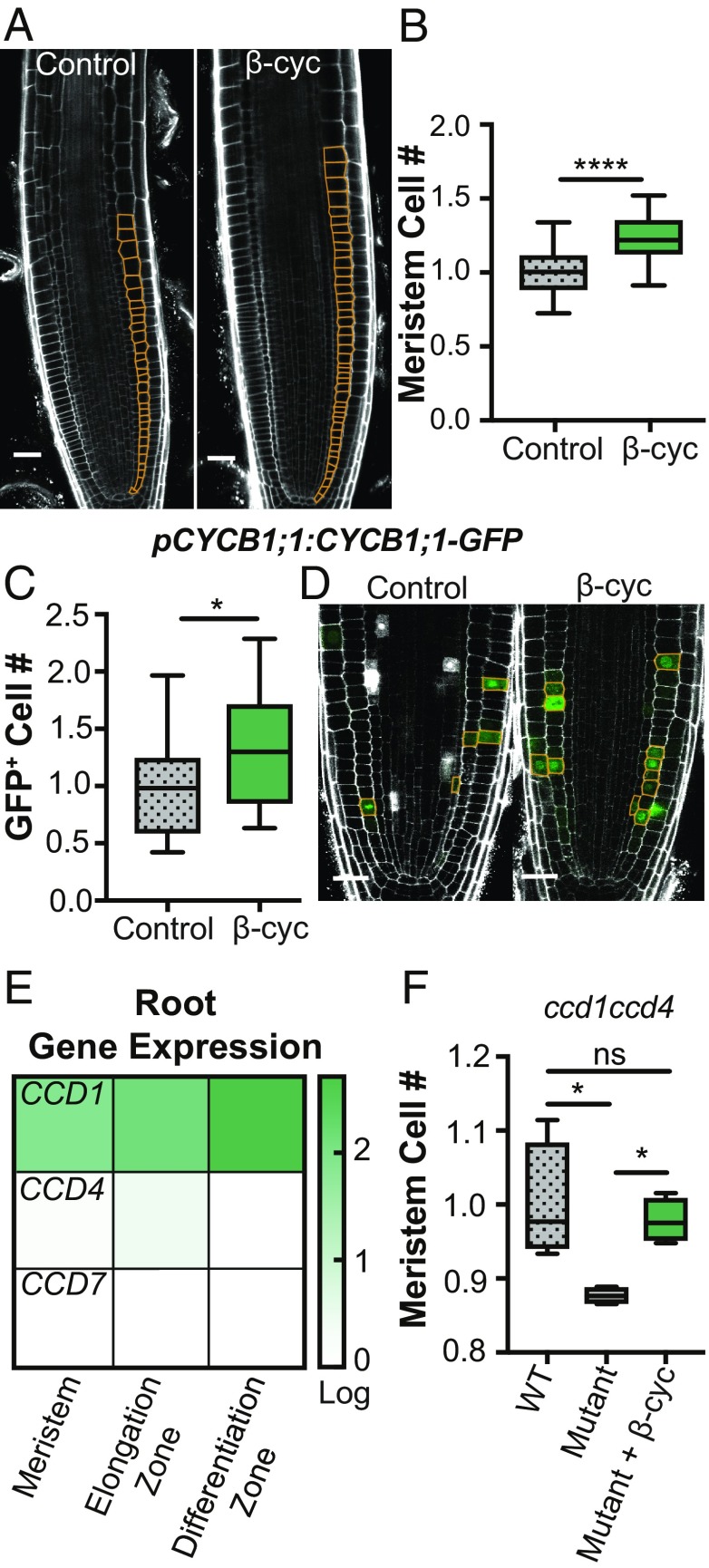

To further determine how β-cyclocitral stimulates root growth and branching, we quantified its effect on the developmental stages in primary roots. Because β-cyclocitral stimulates progenitor cell divisions in LR primordia before cell elongation, we hypothesized that it induces root growth by increasing cell divisions in the root meristem. To test this, we examined meristematic cell numbers and cell elongation in primary roots treated with β-cyclocitral. The number of meristematic cells increased more than 20% upon treatment with β-cyclocitral, while cell elongation remained unchanged (Fig. 2 A and B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). This result suggests that β-cyclocitral enhances divisions in undifferentiated cells in both primary and lateral root meristems. To further test this, we characterized levels of a cyclin-dependent kinase in the meristems of plants harboring the construct pCYCB1;1:CYCB1;1-GFP (Fig. 2 C and D). We found that β-cyclocitral significantly increased the number of GFP-positive cells in the root meristem. These results indicate that β-cyclocitral induces root growth by stimulating meristematic cell divisions.

Fig. 2.

β-Cyclocitral induces meristematic cell divisions in Arabidopsis. (A) Confocal images of primary root meristems. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) Meristematic cortex cells are highlighted in orange. (B) Relative number of cortex cells in the primary root meristems of treated and control plants. (C) Relative number of GFP-positive cells in the root meristem of pCYCB1;1:CYCB1;1-GFP seedlings treated with β-cyclocitral. (D) Confocal images of root meristems in pCYCB1;1:CYCB1;1-GFP seedlings. (Scale bar, 25 μm.) GFP-positive cells are outlined in orange. (E) CCD1, CCD4, and CCD7 gene expression (log[3xFPKM]) in the three developmental zones at the root tip. (F) Relative number of cortex cells in the primary root meristems of WT and ccd1ccd4 double mutants with and without β-cyclocitral. *P = 0.05 and ****P = 0.0001.

To further characterize endogenous β-cyclocitral, we investigated the role of CCD1, CCD4, and CCD7, which cleave β-carotene and may therefore contribute to the formation of β-cyclocitral. Previous work indicated that CCD1 and CCD4 are expressed in the root meristem and elongation zone, but CCD7 is not expressed in the meristem, elongation zone, or beginning of the differentiation zone at the root tip (Fig. 2E) (29, 30). To characterize the effect of enzymatically depleting β-cyclocitral in roots, we generated a ccd1ccd4 double mutant. This mutant had significantly fewer meristematic cells compared with wild-type roots (Fig. 2F). Meristem cell number could be rescued upon application of β-cyclocitral. These data further indicate that β-cyclocitral has an endogenous regulatory role in root development. To determine if β-cyclocitral acts through previously characterized auxin, ROS, or brassinosteriod pathways, which induce meristematic divisions, we quantified the effect of β-cyclocitral on hormone-responsive marker lines and mutants. The auxin-responsive lines pDR5:GFP, pPIN3:PIN3-GFP, pPLT2:CFP, and pPLT2:PLT2-GFP all showed significantly increased meristematic divisions upon β-cyclocitral treatment, yet none had changes in meristem fluorescence (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Moreover, inhibition of auxin transport using N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid did not affect the ability of β-cyclocitral to increase root length (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). We also found no defects in β-cyclocitral induction of root growth in mutants in ROS (upb1-1) and brassinosteroid (bri1-4) signaling pathways (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), suggesting that β-cyclocitral does not regulate meristem divisions through the major pathways that have previously been shown to stimulate meristem growth.

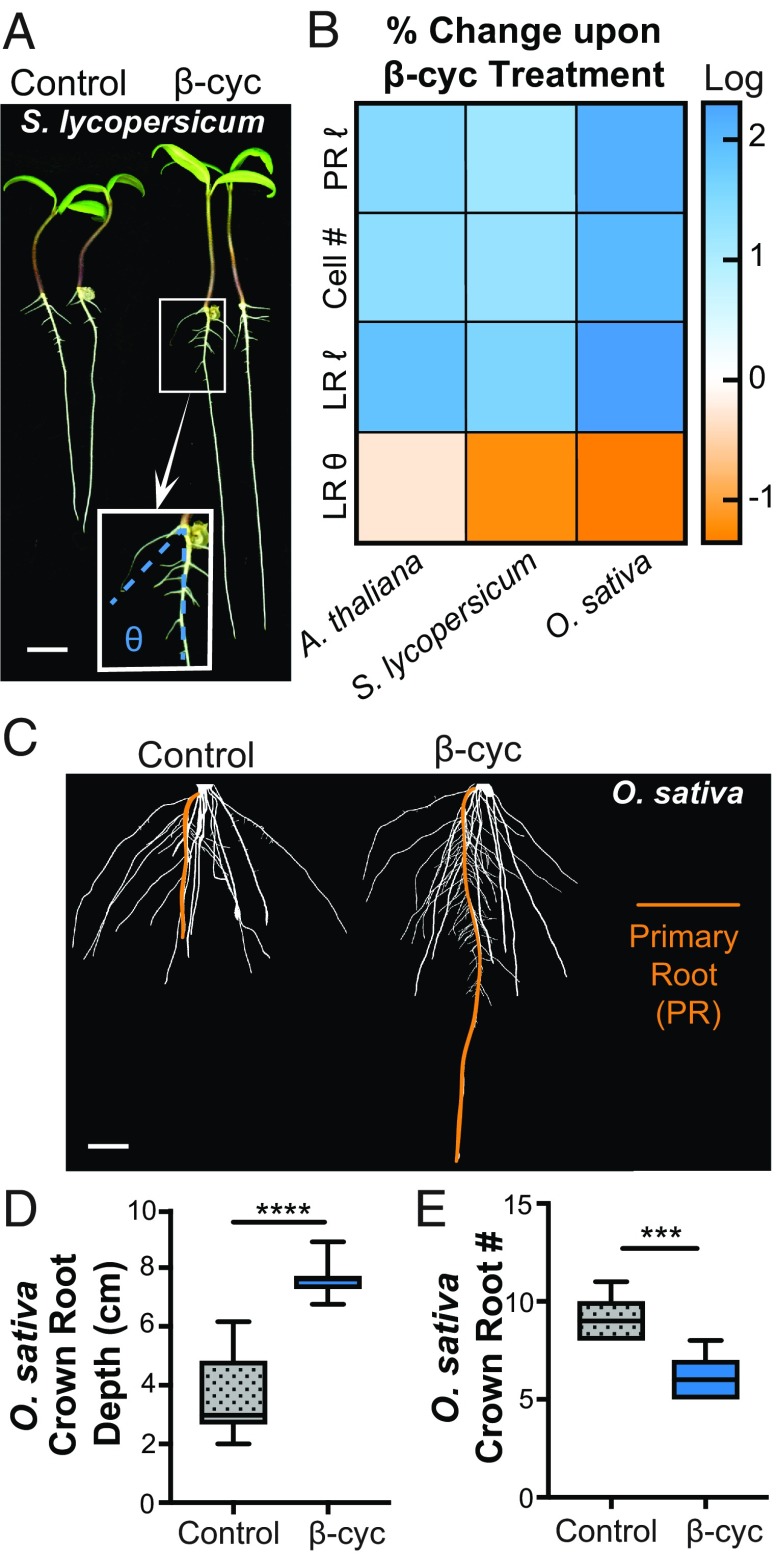

To determine if β-cyclocitral has an effect on agriculturally important plant species, we assayed root growth in tomato and rice seedlings and found that β-cyclocitral significantly increased primary and LR length in Solanum lycopersicum (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9) and in rice seedlings. This result provides strong evidence that β-cyclocitral is a conserved regulator able to stimulate primary and LR length and meristem size in eudicots and monocots (Fig. 3B). In addition, β-cyclocitral reduced the angle between LRs and the primary root—generating steeper root systems—in all three plant species.

Fig. 3.

β-Cyclocitral has conserved effects on root architecture in tomato and rice. (A) Tomato seedlings treated with β-cyclocitral. (Scale bar, 10 mm.) (Inset) The growth angle (θ) between the tip of the LR and the primary root measured to quantify the steepness of LRs is shown in blue. (B) Heat map depicting the increase (blue) or decrease (orange) in primary root length (PR ι), meristematic cell number (Cell #), LR length (LR), and angle of LR growth (LR θ) upon treatment with β-cyclocitral in Arabidopsis, tomato, and rice. (C) Root systems of 9311 rice seedlings treated with β-cyclocitral. (Scale bar, 10 mm.) The primary roots are highlighted in orange. (D) Quantification of the average depth of the crown roots in rice. (E) Quantification of the number of crown roots per seedling. ***P = 0.001 and ****P = 0.0001.

β-Cyclocitral had a striking ability to modify root growth and architecture in 9311, a traditional indica rice cultivar (Fig. 3C). β-Cyclocitral–treated root systems grew twice as deep as control plants and were significantly narrower (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A–C). This change in root system architecture depth, was due, in part, to increased primary root growth, but crown roots also grew about 80% deeper when exposed to β-cyclocitral (Fig. 3D). This effect was due both to an increase in crown root length (SI Appendix, Fig. S10D) and a steeper angle of growth (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 D and E). The total number of crown roots per plant also decreased by nearly 50% (Fig. 3E). The combination of these factors generated deeper, more compact root systems. The overall enhanced root growth caused by β-cyclocitral did not have an obvious effect on shoot mass, which indicates that β-cyclocitral does not have deleterious effects on shoot growth (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). The added complexity of monocot root systems leads to additional emergent phenotypes that would not have been predicted based on the eudicot studies and reveals further potential roles of β-cyclocitral in root development.

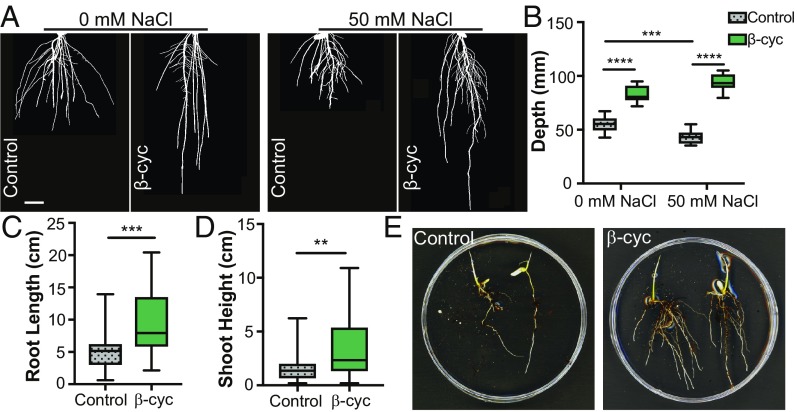

Abiotic stresses such as salinity have a negative effect on plant vigor and root growth. To determine if β-cyclocitral can promote root growth under abiotic stress, we applied it to salt-stressed rice roots (Fig. 4 A and B). Treatment of seedlings with 50 mM sodium chloride (NaCl) in media significantly decreased root depth compared with control treatment. Root depth could be completely recovered upon cotreatment with β-cyclocitral (Fig. 4 A and B). In fact, β-cyclocitral had a significantly larger effect on salt-treated plants compared with unstressed plants (P value = 0.0001, two-way ANOVA). Salt stress also significantly increased the solidity of the root network (SI Appendix, Fig. S12), measured by calculating the total area of each root divided by the convex area of the root system (31). Increased solidity during salt stress indicates that the plants are producing denser and smaller root systems. Although β-cyclocitral does not affect the solidity of the root system in the absence of salt, it rescues solidity during salt treatment. These results indicate that β-cyclocitral not only enhances root growth during normal conditions but also could shield roots from the harmful effects of salt stress. To test whether this could be an effective treatment in a more natural environment, we performed a salt-stress experiment in soil. Rice grown in a heterogeneous salt-contaminated soil environment had significantly longer roots, on average, when treated with β-cyclocitral (Fig. 4 C–E). In addition, this treatment increased shoot height, suggesting that it enhanced overall growth. To test whether this effect during salt stress was conserved, we tested β-cyclocitral application on salt-stressed Arabidopsis roots. β-Cyclocitral increased growth in Arabidopsis, indicating that β-cyclocitral can stimulate root growth in different species under salt stress (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). These results indicate that β-cyclocitral treatment could be a beneficial strategy to enhance root growth and plant vigor in agriculture.

Fig. 4.

β-Cyclocitral promotes rice root growth under salt stress. (A) Rice roots treated with β-cyclocitral and grown in gel with 50 mM NaCl. (Scale bar, 10 mm.) (B) Root system depth in seedlings treated β-cyclocitral and grown in gel with 50 mM NaCl. (C) Primary root length in β-cyclocitral–treated rice plants grown in soil with salt stress. (D) Shoot height in β-cyclocitral–treated rice plants grown in soil with salt stress. (E) Representative images of rice seedlings grown in salt-contaminated soil with and without β-cyclocitral treatment. **P = 0.01, ***P = 0.001, and ****P = 0.0001.

Conclusion

Through a sensitized chemical genetic screen, we identified β-cyclocitral as a naturally occurring β-carotene–derived apocarotenoid, which regulates root architecture in monocots and eudicots. β-Cyclocitral is a natural compound that is inexpensive, active at low concentrations, and can be applied exogenously, making it a promising candidate for agricultural applications. Using Arabidopsis as a model system, we found that β-cyclocitral increases primary root and LR growth by inducing cell divisions in root meristems. β-Cyclocitral additionally has conserved effects as a root growth promoter in tomato and rice. In rice, β-cyclocitral also affects other aspects of root architecture, including the numbers and gravity set-point angle of roots. In salt-stressed rice roots, β-cyclocitral significantly promotes root and shoot growth. These results indicate that β-cyclocitral is a natural compound that could be a valuable tool to improve crop vigor, especially in harsh environmental conditions.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth and Treatment Conditions.

Detailed experimental procedures are provided in SI Appendix. Unless otherwise stated, all Arabidopsis thaliana plants were in the Columbia-0 background, tomato plants were in the S. lycopersicum background, and rice plants were in the 9311 Oryza sativa indica background. Optimized working concentrations of β-cyclocitral (#16976; Sigma Aldrich) in media were 750 nM, 100 μM, and 10 μM for Arabidopsis, tomato, and rice, respectively.

Root Phenotyping.

Lateral root capacity—the number of lateral roots that emerge from the primary root after excision of the primary root apical meristem—was determined as described previously (8). Lateral root clock oscillations were measured as previously described (6). Briefly, roots were sprayed with 5 mM potassium luciferine (Gold Biotechnology) and then were imaged every 7 min over the course of 18 h using a chemiluminescence imaging system (Roper Bioscience). To quantify the number of meristematic cells in the root, cortex meristematic cells were counted. These cells were defined as cortex cells in a single cell file in which the cell length was shorter than 2× the length of the initial cortex cell.

Chemical Analysis.

Briefly, sample preparation for HPLC-MS was performed as follows: the root tissue of 12-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings or 10-d-old hydroponically grown rice seedlings was homogenized in liquid nitrogen. β-Cyclocitral was ultrasonically extracted from 25 mg of homogenized tissue powder spiked with 2 ng D1–β-cyclocitral using MeOH with 0.1% butylated hydroxytoluene. For a more detailed protocol, see SI Appendix.

Data and Materials Availability.

All data are available in the main text or SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jingyuan Zhang for technical support provided for the duration of this project; Michel Havaux, Stefano D’Alessandro, Polly Hsu, and Larry Wu for helpful discussions; Dolf Weijers, Cara Winter, Colleen Drapek, and Isaiah Taylor for critical reading; and Linxing Yao (Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility, Colorado State University) for experimental assistance. This work was supported by the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Postdoctoral Fellowship (to A.J.D.); by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation Grant GBMF3405 (to P.N.B.); and by baseline funding and Competitive Research Grant CRG4 (to S.A.-B.) from King Abdullah University of Science and Technology.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: A.J.D. and P.N.B. have filed a patent application on the use of β-cyclocitral in enhancing root growth.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1821445116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gray WM. (2004) Hormone regulation of plant growth and development. PLoS Bio 2:e311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iqbal N, et al. (2017) Ethylene role in plant growth, development and senescence: Interaction with other phytohormones. Front Plant Sci 8:475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain JL. (2005) Plant Hormones. Fundamentals of Biochemistry (S. Chand & Company, New Delhi: ). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner T, Motyka V, Strnad M, Schmülling T (2001) Regulation of plant growth by cytokinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:10487–10492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malinovsky FG, et al. (2017) An evolutionarily young defense metabolite influences the root growth of plants via the ancient TOR signaling pathway. eLife 6:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreno-Risueno MA, et al. (2010) Oscillating gene expression determines competence for periodic Arabidopsis root branching. Science 329:1306–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malamy JE, Benfey PN (1997) Organization and cell differentiation in lateral roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 124:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Norman JM, et al. (2014) Periodic root branching in Arabidopsis requires synthesis of an uncharacterized carotenoid derivative. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E1300–E1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirschberg J. (2001) Carotenoid biosynthesis in flowering plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 4:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Auldridge ME, McCarty DR, Klee HJ (2006) Plant carotenoid cleavage oxygenases and their apocarotenoid products. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jia K-P, Baz L, Al-Babili S (2018) From carotenoids to strigolactones. J Exp Bot 69:2189–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez-Roldan V, et al. (2008) Strigolactone inhibition of shoot branching. Nature 455:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruyter-Spira C, et al. (2011) Physiological effects of the synthetic strigolactone analog GR24 on root system architecture in Arabidopsis: Another belowground role for strigolactones? Plant Physiol 155:721–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Smet I, Zhang H, Inzé D, Beeckman T (2006) A novel role for abscisic acid emerges from underground. Trends Plant Sci 11:434–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramel F, et al. (2012) Carotenoid oxidation products are stress signals that mediate gene responses to singlet oxygen in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:5535–5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shumbe L, Bott R, Havaux M (2014) Dihydroactinidiolide, a high light-induced β-carotene derivative that can regulate gene expression and photoacclimation in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant 7:1248–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laloi C, Havaux M (2015) Key players of singlet oxygen-induced cell death in plants. Front Plant Sci 6:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tieman D, et al. (2012) The chemical interactions underlying tomato flavor preferences. Curr Biol 22:1035–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinge V, Patil H, Nadaf A (2016) Comparative characterization of aroma volatiles and related gene expression analysis at vegetative and mature stages in Basmati and non-Basmati rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 178:619–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linde GA, et al. (2016) Antifungal and antibacterial activities of Petroselinum crispum essential oil. Genet Mol Res 15:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojha PK, Roy K (2018) PLS regression-based chemometric modeling of odorant properties of diverse chemical constituents of black tea and coffee. RSC Adv 8:2293–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen WK, et al. (2017) Comparison of transcriptional expression patterns of carotenoid metabolism in ‘Cabernet Sauvignon’ grapes from two regions with distinct climate. J Plant Physiol 213:75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tewari G, Mohan B, Kishor K, Tewari LM, Nailwal TK (2015) Volatile constituents of Ginkgo biloba L. leaves from Kumaun: A source of (E)-nerolidol and phytol. J Indian Chem Soc 92:1583–1586. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez E, Ledbetter CA (1997) Development of volatile compounds during fruit maturation: Characterization of apricot and plum x apricot hybrids. J Sci Food Agric 74:541–546. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saritas Y, et al. (2001) Volatile constituents in mosses (Musci). Phytochemistry 57:443–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomita K, et al. (2016) Characteristic oxidation behavior of β-cyclocitral from the cyanobacterium Microcystis. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 23:11998–12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkar AK, et al. (2007) Conserved factors regulate signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana shoot and root stem cell organizers. Nature 446:811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreno-Risueno MA, et al. (2015) Transcriptional control of tissue formation throughout root development. Science 350:426–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li S, Yamada M, Han X, Ohler U, Benfey PN (2016) High-resolution expression map of the Arabidopsis root reveals alternative splicing and lincRNA regulation. Dev Cell 39:508–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Booker J, et al. (2004) MAX3/CCD7 is a carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase required for the synthesis of a novel plant signaling molecule. Curr Biol 14:1232–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galkovskyi T, et al. (2012) GiA roots: Software for the high throughput analysis of plant root system architecture. BMC Plant Biol 12:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.