Significance

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the fuel of biology, is produced by a molecular machine with a rotary action. Inside the mitochondria of eukaryotic cells, rotation is driven by a proton-motive force across the inner membranes of the organelle generated by oxidation of sugars and fats in food. Under anoxic conditions, the rotary machine hydrolyzes ATP and reverses rotation. This wastage is prevented by an intrinsically disordered region of the inhibitor protein, IF1, which inserts itself in the machine and stops reverse rotation. The inhibitory activity of IF1 is regulated by self-association, which is influenced by pH and ion-types, providing a potential molecular mechanism for the modulation of ATPase activity by cellular physiology via this solution-responsive, self-associating protein.

Keywords: mitochondria, ATP hydrolysis, regulation, inhibitor, intrinsically disordered protein

Abstract

The endogenous inhibitor of ATP synthase in mitochondria, called IF1, conserves cellular energy when the proton-motive force collapses by inhibiting ATP hydrolysis. Around neutrality, the 84-amino-acid bovine IF1 is thought to self-assemble into active dimers and, under alkaline conditions, into inactive tetramers and higher oligomers. Dimerization is mediated by formation of an antiparallel α-helical coiled-coil involving residues 44–84. The inhibitory region of each monomer from residues 1–46 is largely α-helical in crystals, but disordered in solution. The formation of the inhibited enzyme complex requires the hydrolysis of two ATP molecules, and in the complex the disordered region from residues 8–13 is extended and is followed by an α-helix from residues 14–18 and a longer α-helix from residue 21, which continues unbroken into the coiled-coil region. From residues 21–46, the long α-helix binds to other α-helices in the C-terminal region of predominantly one of the β-subunits in the most closed of the three catalytic interfaces. The definition of the factors that influence the self-association of IF1 is a key to understanding the regulation of its inhibitory properties. Therefore, we investigated the influence of pH and salt-types on the self-association of bovine IF1 and the folding of its unfolded region. We identified the equilibrium between dimers and tetramers as a potential central factor in the in vivo modulation of the inhibitory activity and suggest that the intrinsically disordered region makes its inhibitory potency exquisitely sensitive and responsive to physiological changes that influence the capability of mitochondria to make ATP.

The mitochondrial ATP synthases, also known as F-ATPases or F1Fo-ATPases, are multisubunit enzymes found in the inner membranes of the organelle (1, 2). Under aerobic conditions, they make ATP from ADP and phosphate using a proton-motive force (pmf) generated by respiration, as a source of energy to drive their rotary mechanism. If the pmf is dissipated, for example, during ischemia, the enzyme reverses its direction of rotation and starts to hydrolyze ATP, but this hydrolytic activity becomes inhibited by a protein known as IF1 (3). The active state, which is present at pH values around neutrality (4), binds to one of the three catalytic sites of the membrane extrinsic F1-domain of the enzyme, stopping hydrolysis (5, 6). Bovine IF1 is a basic protein of 84 amino acids (7, 8). In a structure of bovine F1-ATPase inhibited with a monomeric fragment consisting of residues 1–60 of bovine IF1, residues 1–46 are bound in one of the three catalytic interfaces of the enzyme with the N-terminal region of the inhibitor penetrating from outside the enzyme into an internal aqueous cavity surrounding part of the enzyme’s rotor (6). Residues 1–7 of IF1 were unresolved; residues 8–13 form an extended structure, linked to an α-helix from residues 14–18 that interacts with the γ-subunit in the rotor. This α-helix is attached by a turn from residues 19–20 to a second α-helix from residues 21–50, which interacts with other α-helices in the C-terminal domains of the α- and β-subunits in the αDPβDP-catalytic interface, the most closed of the three catalytic interfaces. From residues 47–50, the long α-helix extends beyond the surface of the enzyme, and the remainder of truncated IF1 was unresolved. In crystals of IF1 alone, the protein is disordered from residues 1–18 and α-helical from residues 19–83 and is dimerized by an antiparallel α-helical coiled-coil from residues 44–84 (9). The dimers form tetramers and higher oligomers, and the formation of tetramers occludes the N-terminal inhibitory region. In solution, the dimerization of dimers and occlusion of the inhibitory region is pH-dependent (4). At pH values below about 7.5, IF1 is an active dimer, and at higher pH values, tetramers and oligomers form, and IF1 is inactive. The mutation H49K (10) abolishes the ability to form tetramers, and the mutated dimeric IF1 is constitutively active and pH-independent (4). In solution, the C-terminal region of IF1 forms a dimeric α-helical coiled-coil on its own, whereas the N-terminal inhibitory region is unstructured (11) and provides an example of an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) (12). During inhibition of F1-ATPase, the disordered region interacts with the most open of the three catalytic sites and becomes α-helical from residues 31–49. Hydrolysis of two ATP molecules converts this open site with bound IF1 to, first, a partially closed site, where residues 23–50 of IF1 are α-helical region, and then to the fully closed state, where the inhibitory region is structured to its greatest extent (12).

IDPs are characterized by a lack of defined structure and they populate many different conformational states (13, 14). They are prevalent, especially in higher eukaryotes, and they are functional and more responsive to solution conditions than folded proteins. Factors such as ionic strength (15), pH (16), temperature (17), and molecular crowding (18) all have an impact on IDPs by influencing, for example, their radius of gyration and the collapse of unfolded polypeptide chains. These enhanced sensitivities to environmental factors can be ascribed to their shallower energy landscapes, and these factors can influence directly the binding profiles of coupled folding and binding processes (19), as with the influence of pH on the oligomeric state of IF1 (4). Mitochondria respond to changes in physiological conditions by taking up and releasing Ca2+, K+, and other cations via specific channels (20). Therefore, as described here, we have studied the influence of pH and cation-types on the structure and oligomeric state of IF1 in solution.

Results

Dependence of the Oligomerization of IF1 on pH.

The oligomeric state of IF1 was investigated by covalent cross-linking IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K with 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC) from pH 3.3–8.0. The mutation Y33W has no effect on the inhibitory properties of the protein (21). Around neutral pH, IF1-Y33W formed tetramers, whereas IF1-Y33W-H49K was primarily dimeric (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). With decreasing pH, IF1-Y33W dissociated to dimers, and ultimately, both proteins became monomeric. As the multimeric species were most abundant at neutral pH, which is beyond the optimal range for the reactivity of EDC from pH 4.6–6.0, these results report on the effect of pH on the oligomerization of IF1 and not on the chemical reactivity of the cross-linker.

Covalent cross-linking provides information about the presence or absence of given species, but does not reflect the distribution of oligomeric states in solution at equilibrium. Therefore, analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) was performed at pH 2.4, 4.0, and 6.9 (SI Appendix, Figs. S1B and S2 and Table S1). At pH 2.4, both IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K were monomeric. At pH 4.0, both proteins had similar sedimentation coefficients, and their estimated masses were consistent with coalesced distributions of monomeric and dimeric species. At pH 6.9, the behavior of the two proteins diverged markedly, with IF1-Y33W having a much larger sedimentation coefficient than at pH 4.0, consistent with it being tetrameric, whereas the value for IF1-Y33W-H49K did not change extensively and indicated that it was dimeric. The fractional ratio (f/f0) of both proteins diminished with increasing pH values, indicative of the formation of more folded structures. Thus, this work confirmed that the oligomeric state of IF1 is dependent on pH, and the mutation H49K suppresses tetramerization.

Effect of pH on the Structure of IF1.

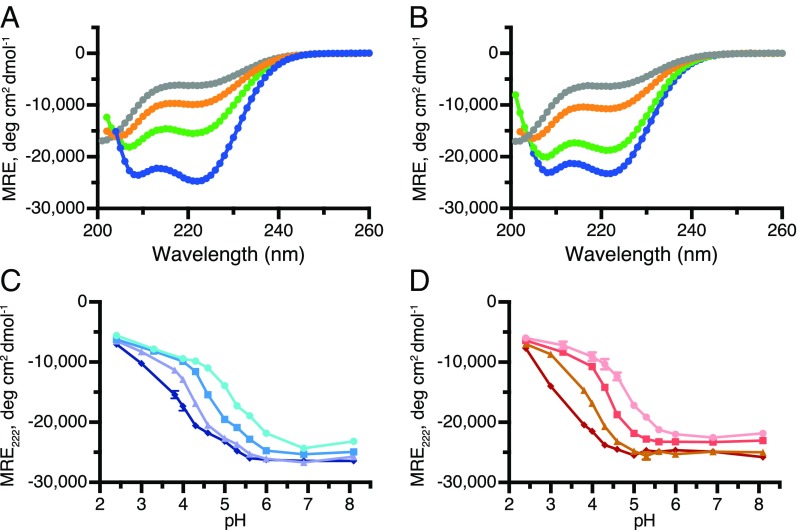

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy allows the bulk secondary-structure profiles of proteins to be determined and is particularly sensitive to the α-helical content. Both IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K underwent a helix-coil transition as a function of pH (Fig. 1 A and B). At pH 2.0, the spectra of both proteins were consistent with the presence of unfolded states containing some residual helicity (∼18%). In contrast, toward neutral pH about 70% of the proteins were α-helical. The degree of helicity of IF1-Y33W-H49K and IF1-Y33W did not differ greatly, suggesting that the tetramer is not folded much more than the dimer. No changes in secondary structure were observed in the alkaline region up to about pH 10 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 1.

Changes in secondary structure induced by pH. (A and B) CD spectra of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K, respectively, at protein concentrations of 10 μM and pH values of 2.4 (gray), 4.0 (orange), 4.6, (green) and 6.0 (blue). (C and D) Dependence of helicity of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K, respectively, on pH at various protein concentrations. IF1-Y33W: 1 μM (light blue line); 10 μM (medium blue line); 50 μM (light purple line); 100 μM (dark blue line). IF1-Y33W-H49K: 1 μM (pink line); 10 μM (red line); 50 μM (brown line); 100 μM (maroon line). In C and D, error bars denote the range of values measured.

Dependence of the pH-Induced Coil-to-Helix Transition on Protein Concentration.

To confirm that the loss of secondary structure observed by CD was related to the disassembly of the oligomers detected by AUC and cross-linking, pH profiles of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K were measured at protein concentrations spanning two orders of magnitude (1–100 μM). A clear shift of the transition midpoint (Fig. 1 C and D) is consistent with concentration-dependent events. The pH profiles of both IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K have single transitions, consistent with concomitant folding and oligomerization. The single transition with IF1-Y33W also suggests that the formation of dimers and tetramers as a function of pH is either cooperative, or that the events are merged significantly. Thus, it appears that the stabilities of the dimeric and tetrameric species are similar with respect to pH.

To confirm the results from CD spectroscopy, IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K were reacted with EDC at the same 100-fold range of protein concentrations and at pH values of 5.3 and 7.0. As expected, oligomers were more abundant at higher protein concentrations, confirming the concentration dependence of the oligomerization of IF1 observed by CD (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Role of the C-Terminal Region of IF1 in Oligomerization.

The role of the C-terminal part of IF1 and the effect of pH on the formation of oligomers of IF1 was studied with I1-62-Y33W-H49K and I1-62-Y33W, versions of IF1 that are C-terminally truncated at residue 62 and lack the capacity to dimerize, with and without the mutation H49K. The pH profiles and concentration dependence of both proteins revealed disordered structures under all conditions of pH and protein concentrations investigated (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A and B). Importantly, the residual helicity was almost entirely independent of either parameter (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). These results are consistent with unfolded monomers, as confirmed by covalent cross-linking, which revealed virtually no oligomeric species (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D). Thus, the C-terminal region is required for both dimerization and tetramerization of IF1.

Energetics of Oligomerization of IF1.

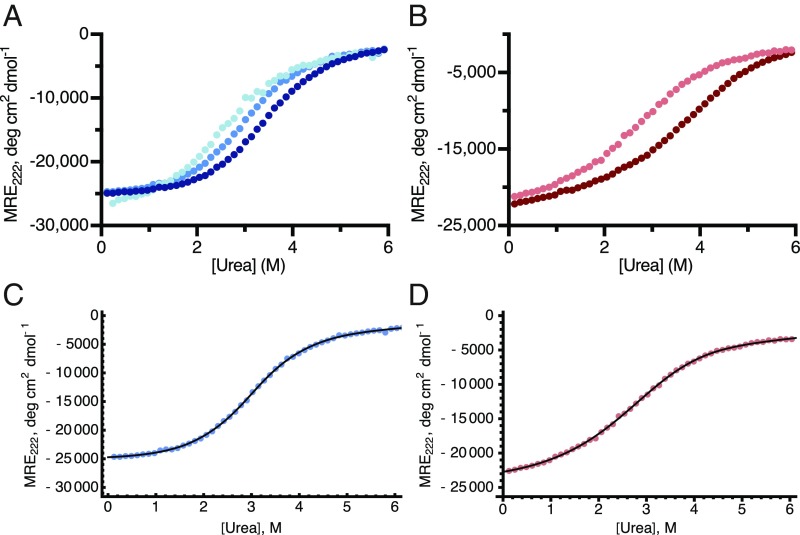

The oligomerization of IF1 was studied quantitatively by chemical denaturation with urea. Chemical denaturation has been used extensively to study the folding stability of both monomeric proteins and oligomers (22–24). However, beyond dimers, the mathematical formulation for data analysis becomes less trivial, and fewer systems have been investigated (25, 26). Here, models describing two-state (monomer/dimer) homodimerization, two-state (monomer/tetramer) homotetramerization, and three-state (monomer/dimer/tetramer) homotetramerization were developed (SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods), allowing equilibrium constants between the different oligomeric states to be obtained from the chemical denaturation data. Denaturation with urea of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K produced single transitions, and their positions depended on the protein concentration, as expected for oligomeric species (Fig. 2 A and B). Cross-linking experiments in the presence of urea confirmed that the spectral changes observed by CD were associated with the dissociation of oligomers of IF1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The reversibility of chemical denaturation was confirmed in a refolding experiment (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

Fig. 2.

Chemical denaturation of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K. (A and B) Urea denaturation at pH 7.0 of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K, respectively, at various concentrations of proteins. (A) 1 µM (light blue), 3 µM (medium blue), and 9 µM (dark blue); (B) 1 µM (pink) and 10 µM (red). (C and D) Representative fittings of data from chemical denaturation at pH 7.0 of IF1-Y33W (3 µM; blue) and IF1-Y33W-H49K (1 µM; pink), respectively. Fitted curves are depicted in black, and the colored dots are experimental values.

The CD spectral signatures of each species (the baselines) in denaturation experiments hold structural information. Thus, the α-helical contents estimated from molar residue ellipticity (MRE) values at 222 nm revealed that at pH 7.0, the tetramer and dimer were approximately 72 and 62% α-helical, respectively (folded species), whereas the monomers were ∼12% α-helical (consistent with a disordered protein). Thus, the oligomerization of IF1 is a coupled folding and binding reaction where monomers cannot fold autonomously and acquire their α-helical structures by self-assembly. Even at neutral pH, the monomeric state of the protein is unfolded, confirming that IF1 on its own is an IDP.

Effect of pH on Tetramerization and Dimerization.

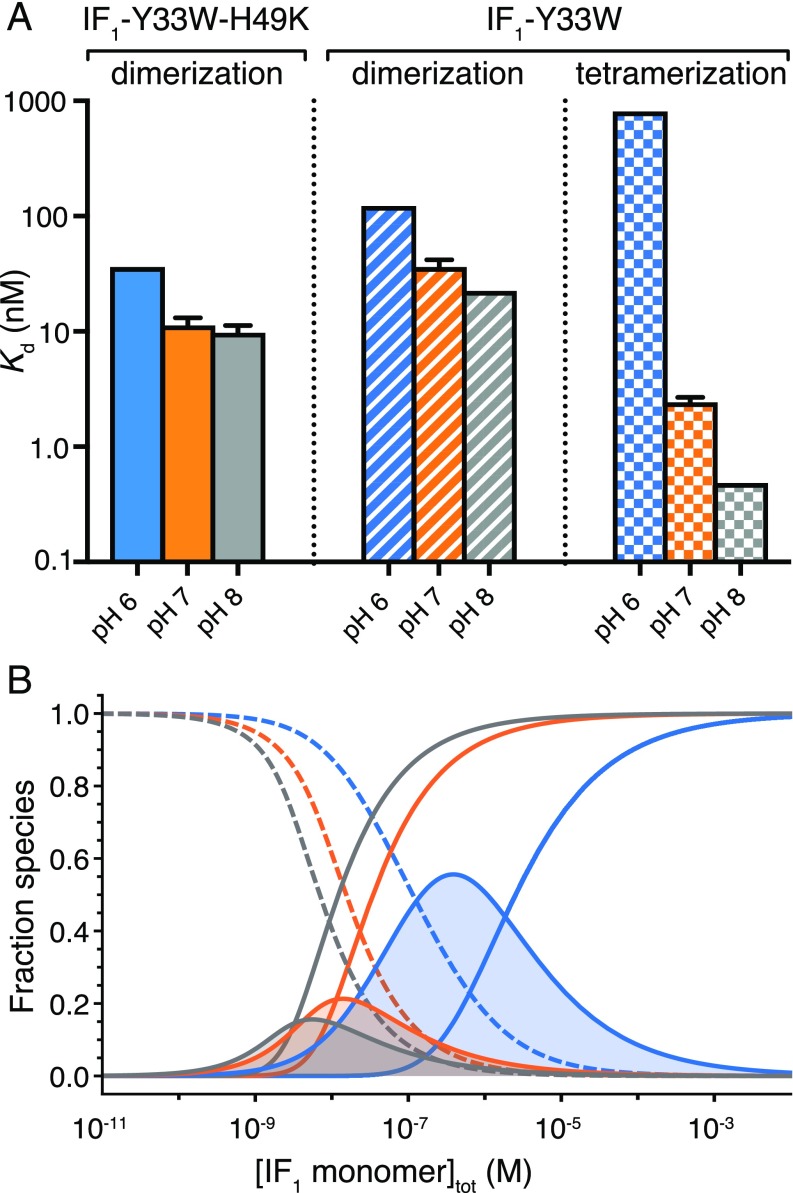

Equilibrium denaturation curves of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W H49K at pH values of 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0 were obtained, and the data for IF1-Y33W-H49K were fitted to the two-state homodimerization model (Fig. 2 C and D), and the extracted free energies of oligomerization were converted to Kd values (Fig. 3A, Table 1, and SI Appendix, Table S2). The affinity of the dimer of IF1-Y33W-H49K was in the low nanomolar regime. More acidic conditions destabilized the dimer, as expected from the qualitative results. However, over the pH range of 6–8, the Kd value was relatively insensitive to pH, changing only by fourfold.

Fig. 3.

Effect of pH on dimerization and tetramerization of IF1. (A) Values of Kd for IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0 obtained from chemical denaturation experiments. (B) Simulation of fractional oligomeric distribution for IF1-Y33W at pH 6.0 (blue), pH 7.0 (orange), and pH 8.0 (gray). The monomeric, dimeric, and tetrameric species are indicated as dashed, solid with filled areas beneath, and solid lines, respectively.

Table 1.

Parameters from fitting the two-state dimerization model to the data for IF1-Y33W-H49K at various pH values

| pH | ΔG, kcal mol−1* | Kd, nM* |

| 6 (n = 1) | 10.15 | 36.13 |

| 7 (n = 3) | 10.84 ± 0.09 | 11.30 ± 1.82 |

| 8 (n = 2) | 10.93 ± 0.09 | 9.72 ± 1.51 |

Errors denote SDs.

The spectroscopic signatures for the dimer and the tetramer species are similar (vide supra), and there was no clear biphasic transition for the chemical denaturation of IF1-Y33W. Thus, it was not obvious whether or not a dimeric intermediate is populated at equilibrium. However, the chemical denaturation data of IF1-Y33W were best described by the three-state tetramerization model (SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods) (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Tables S3–S5). Since this model explicitly describes a dimeric intermediate, the effects of pH on the tetramerization (tetramer to dimer) and on the dimerization (dimer to monomer) of IF1-Y33W could be quantified (Table 2). As with IF1-Y33W-H49K, dimerization was relatively insensitive to pH, and the affinity only varied by approximately fivefold over the pH range investigated. In contrast, the affinity of the tetrameric species varied by three orders of magnitude over the same pH range, demonstrating that it is the extent of tetramerization, and not dimerization, that is modulated primarily by pH.

Table 2.

Parameters obtained by fitting the three-state tetramerization model to the data of IF1-Y33W at various pH values

| pH | ΔG1, kcal mol−1* | ΔG2, kcal mol−1* | Kd1, nM* | Kd2, nM* |

| 6 (n = 1) | 8.30 | 9.42 | 811.25 | 122.33 |

| 7 (n = 3) | 11.75 ± 0.07 | 10.15 ± 0.09 | 2.42 ± 0.26 | 36.16 ± 5.76 |

| 8 (n = 1) | 12.70 | 10.43 | 0.48 | 22.47 |

ΔG1 and Kd1 refer to the tetramer/dimer transition; ΔG2 and Kd2 refer to the dimer/monomer transition.

Errors denote SDs.

As the Kd values for the tetramer formation and for the dimer formation of IF1-Y33W are close in magnitude, the dimeric intermediate is never populated on its own under the conditions investigated, consistent with the lack of a biphasic transition in the unfolding data. Nevertheless, the differential effect of pH on the affinities of the tetramer and dimer species signifies that the fraction of the dimer present varies greatly as a function of pH (Fig. 3B). Thus, even a relatively small change in solution conditions can have a dramatic impact on the distribution of oligomeric states, which in turn is likely to affect the extent of inhibition of the hydrolytic activity of the ATP synthase by IF1.

Cation Dependence of the Stability of Oligomers.

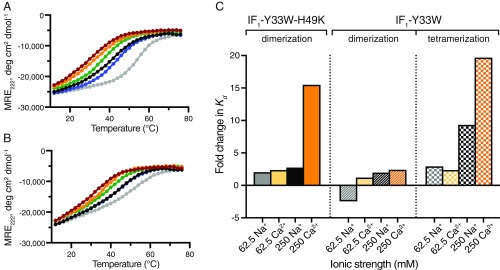

Samples of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K were melted in the presence of various salts at a constant ionic strength of 1 M and neutral pH, and the disassembly of IF1 oligomers was followed as a loss of helicity by CD spectroscopy at 222 nm (Fig. 4 A and B). Disassembly was influenced by cations, and the order of stability followed the Hofmeister series, calcium ions having the strongest destabilizing effect, as observed with other IDP systems (19). Moreover, the shift in the midpoint of the unfolding transition was more pronounced for IF1-Y33W than for IF1-Y33W-H49K, suggesting that the tetramer is more sensitive than the dimer to ionic conditions. This observation echoes the results obtained for the pH sensitivity of the different oligomeric transitions.

Fig. 4.

Effect of ionic strength and cation-type on the oligomerization of IF1. (A and B) Thermal denaturation of IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W-H49K, respectively. Unfolding was assessed by monitoring the change in the MRE value at 222 nm as a function of temperature. Samples were at protein concentrations of 3 µM in 10 mM MOPS, pH 7.0, containing chloride salts of the indicated cations (total ionic strength of 1 M); gray, MOPS alone (total ionic strength 4 mM); K+, blue; Na+, black; Li+, green; Mg2+, orange; Ca2+, maroon. (C) Fold changes in Kd values compared with condition with no salt. The values were obtained from fitting chemical denaturation data. The ionic strength corresponding to each condition is indicated next to the ion.

To gain a quantitative understanding of the effects of ion-types, dissociation constants were estimated from chemical denaturation experiments. Sodium ions and calcium ions were investigated at two values of ionic strength, as was the absence of any salt (Fig. 4C). In all cases, calcium ions had a stronger destabilizing effect than sodium, consistent with the Hofmeister series and the thermal melt experiments. As expected from the Hofmeister effect, higher ionic strengths led to greater differences between sodium and calcium. Thus, the oligomerization of IF1 is influenced by the nature of the surrounding cations.

Discussion

Qualitatively, the oligomerization of IF1 depends upon pH. At neutrality, the pseudowild-type inhibitor protein, IF1-Y33W was tetrameric, and the mutant inhibitor IF1-Y33W-H49K was dimeric. These oligomers disassembled with decreasing pH. However, minor deviations of pH toward acidic values had important effects on the assemblage of oligomeric states. In contrast, changes of pH of the same magnitude toward increasingly alkaline values had very little effect, highlighting the sensitivity of the state of IF1 to acidic environments. These effects probably relate to the biological function of IF1, as its oligomeric states inhibit the hydrolytic activity of ATP synthase to different extents (4).

However, the oligomerization of IF1 is not simply the association of folded monomers. Instead, the folding and self-association processes are coupled. Under conditions where the protein was monomeric, it was also disordered. Therefore, the protein cannot fold autonomously, and it gains helicity by forming interchain contacts. Thus, we emphasize that the thermodynamic parameters relating to the dimer/monomer transition reported here contain the contributions from both folding and binding and that these cannot be deconvoluted. The obligate multimeric nature of the folding event also implies that the stability of the structured state(s) is (are) concentration-dependent, as confirmed by the transition midpoint of the pH curve being a function of the total protein concentration. As the extents of helicity of the dimer and tetramer appear to be similar, this additional oligomerization step appears not to contribute significantly to folding.

The multimeric nature of IF1 has important implications for the stability of its structured state(s), and protein concentration will influence the distribution of oligomeric species at equilibrium, probably affecting the inhibitory potency of IF1. Thus, oligomerization was quantified as a function of pH by chemical denaturation. This approach for studying IF1 was validated, and quantitative models were developed for both dimerization and tetramerization. The pseudowild-type IF1-Y33W gave a single transition, suggesting a fully cooperative transition of tetramer to monomer. However, the two-state model did not properly capture the data, suggesting the presence of a lowly populated intermediate (a complete discussion of the shortcomings of the two-state tetramerization model can be found in SI Appendix, Supplementary Methods). Given all of the other independent supporting evidence, this intermediate was assigned as the dimer and the data fitted to a three-state tetramerization model.

Quantitatively, the influence of pH on the assembly of both IF1-Y33W and IF1-Y33W H49K differed markedly. Whereas the dimerization of both proteins was relatively insensitive in the pH range 6–8 (with Kd values varying by only four- to fivefold), the tetramerization of IF1-Y33W was extremely sensitive (the Kd value varied about 1,700-fold over the same pH range). Therefore, it is the extent of tetramerization, and not dimerization, that is affected most strongly by changes in pH within the physiological range. All five histidine residues of IF1 are in its C-terminal region, and in the structure of IF1, this region is involved in dimerization via an antiparallel α-helical coil-coil. In bovine IF11–60, the pKa values of these histidines are in the range of 6.2–6.8 (11). Thus, changes in pH might be expected to affect dimerization strongly, with increasing protonation of these residues affecting primarily the stability of the dimer. However, it is the tetramer/dimer transition that is most affected in solution. The greater number of protein chains present in the tetramer and the resulting additive effect of protonating a histidine site per chain could explain this behavior. Moreover, if these histidines were in close spatial proximity in the structure of the tetramer, these effects would become nonadditive and could compound in terms of stability, resulting in even greater sensitivity. However, for this to be the case, the structure of the IF1 tetramer in solution would have to be different from the fibrillar crystal structure where such contacts are absent (9).

At the values of pH investigated here, the magnitudes of the Kd values for the tetramer and dimer species of IF1-Y33W are relatively similar, and therefore the dimeric intermediate is never present on its own, and represents only a fraction of the total protein concentration. However, because of the differential effect of pH on the affinities of the tetramerization and dimerization events, the fraction of dimer varies greatly with pH (Fig. 4B). At a concentration of a 100 nM, for example, the distribution at pH 8.0 is ∼80% tetramer and ∼10% for both monomer and dimer. At pH 6.0, this distribution has changed to <5% tetramer and ∼50% of both monomer and dimer. However, not all protein concentrations give rise to similar redistributions. For example, at a protein concentration of IF1 of 10 nM, the fraction of dimer never exceeds ∼20%, regardless of pH. Thus, the population of oligomeric states in the mitochondrial matrix at a particular pH value will depend on the total concentration of IF1 in the organelle. While these observations are likely to be physiologically relevant, as yet, there are no accurate estimates of the in organello concentrations of IF1, although it is clearly an abundant protein (27).

Another potentially physiologically relevant finding is that the oligomeric stability of IF1 is sensitive to both ionic strength and the nature of surrounding cationic species. As in other IDP systems (19), the order of stability followed the Hofmeister series. Most significantly, the presence of mM concentrations of Ca2+ had a significant destabilizing effect, especially on tetramerization. Although the changes were relatively modest (a few fold), and the observations were made at pH 7.0, it seems probable that at more acidic pH values, where the stability of the oligomers is already marginal, the effects of cations will become more pronounced. Thus, in mitochondria, it is likely that the oligomeric state of IF1 and its inhibitory potency are modulated by a combination of pH and cation-type. Moreover, the intrinsically disordered nature of IF1 makes its inhibitory potency exquisitely sensitive and responsive to any physiological changes that may influence the capability of the mitochondria to make ATP. The concentrations of free cations in the mitochondrial matrix are difficult to estimate because of the presence of phosphate at changing levels and also of proteins, DNA and RNA molecules. Nonetheless, it is generally assumed that the concentration of K+ ions is about 100 mM, similar to the cytosol (28). One estimate of the concentration of free Mg2+ in the mitochondrial matrix is that it is about 0.67 mM (29) and that of Na+ about 10 mM (30). The concentration of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in most cells is 0.05–0.5 µM, and the mitochondria act as a temporary store for Ca2+ in the form of a calcium phosphate gel when the mitochondrial concentration exceeds a set point, which varies from 0.3 to 1 µM (28). In the mitochondrial concentration range of 0.1–1 µM, Ca2+ regulates the activities of three central mitochondrial enzymes, pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate synthase, and 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase (31). It now seems likely that the influx of Ca2+ into mitochondria has a fourth important physiological role in increasing the inhibitory potency of IF1, leading to the rapid inactivation of the ATPase, as observed earlier (32).

Materials and Methods

Variants of bovine IF1 were expressed and purified as described previously (4) and characterized by mass spectrometry (SI Appendix, Table S6). The oligomeric state of proteins was examined by covalent cross-linking and analytical centrifugation. The helicity of proteins was determined by CD spectroscopy. Proteins were denatured with urea, and CD spectra were recorded at intervals. Changes in MRE222 as a function of urea concentration were fitted to appropriate homooligomerization models to extract thermodynamic parameters by nonlinear least squares minimization routines (SI Appendix, Tables S2–S4). For further details, see SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. K. Stott and Mr. P. Sharratt (both Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge) for assistance with the AUC experiments and amino acid analysis, respectively; and Dr. S. Ding and Mr. M. G. Montgomery (both Medical Research Council Mitochondrial Biology Unit, Cambridge) for measuring molecular masses and help in preparing the manuscript, respectively. B.I.M.W. was supported by the Cambridge Trust, St. Catharine’s College, Cambridge and the Cambridge Philosophical Society. J.C. is a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellow. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council, UK by Grants MC_U105663150, MC_UU_00015/8, and MR/M009858/1 (to J.E.W.) and by the Wellcome Trust by Grant WT095195 (to J.C.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1903535116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Walker JE. (2013) The ATP synthase: The understood, the uncertain and the unknown. Biochem Soc Trans 41:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker JE. (2017) Structure, mechanism and regulation of ATP synthases. Mechanisms of Primary Energy Transduction in Biology, ed Wikström M. (Royal Soc of Chem, Cambridge, UK: ), pp 338–373. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pullman ME, Monroy GC (1963) A naturally occuring inhibitor of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate. J Biol Chem 238:3762–3769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cabezon E, Butler PJ, Runswick MJ, Walker JE (2000) Modulation of the oligomerization state of the bovine F1-ATPase inhibitor protein, IF1, by pH. J Biol Chem 275:25460–25464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cabezón E, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE (2003) The structure of bovine F1-ATPase in complex with its regulatory protein IF1. Nat Struct Biol 10:744–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gledhill JR, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE (2007) How the regulatory protein, IF1, inhibits F1-ATPase from bovine mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:15671–15676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frangione B, Rosenwasser E, Penefsky HS, Pullman ME (1981) Amino acid sequence of the protein inhibitor of mitochondrial adenosine triphosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78:7403–7407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker JE, Gay NJ, Powell SJ, Kostina M, Dyer MR (1987) ATP synthase from bovine mitochondria: Sequences of imported precursors of oligomycin sensitivity conferral protein, factor 6, and adenosinetriphosphatase inhibitor protein. Biochemistry 26:8613–8619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabezón E, Runswick MJ, Leslie AGW, Walker JE (2001) The structure of bovine IF1, the regulatory subunit of mitochondrial F-ATPase. EMBO J 20:6990–6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnizer R, Van Heeke G, Amaturo D, Schuster SM (1996) Histidine-49 is necessary for the pH-dependent transition between active and inactive states of the bovine F1-ATPase inhibitor protein. Biochim Biophys Acta 1292:241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon-Smith DJ, et al. (2001) Solution structure of a C-terminal coiled-coil domain from bovine IF1: The inhibitor protein of F1 ATPase. J Mol Biol 308:325–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bason JV, Montgomery MG, Leslie AGW, Walker JE (2014) Pathway of binding of the intrinsically disordered mitochondrial inhibitor protein to F1-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:11305–11310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eliezer D. (2009) Biophysical characterization of intrinsically disordered proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol 19:23–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Lee R, et al. (2014) Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem Rev 114:6589–6631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller-Späth S, et al. (2010) From the Cover: Charge interactions can dominate the dimensions of intrinsically disordered proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:14609–14614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann H, Nettels D, Schuler B (2013) Single-molecule spectroscopy of the unexpected collapse of an unfolded protein at low pH. J Chem Phys 139:121930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wuttke R, et al. (2014) Temperature-dependent solvation modulates the dimensions of disordered proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:5213–5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soranno A, et al. (2014) Single-molecule spectroscopy reveals polymer effects of disordered proteins in crowded environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:4874–4879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wicky BIM, Shammas SL, Clarke J (2017) Affinity of IDPs to their targets is modulated by ion-specific changes in kinetics and residual structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:9882–9887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szabo I, Zoratti M (2014) Mitochondrial channels: Ion fluxes and more. Physiol Rev 94:519–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bason JV, Runswick MJ, Fearnley IM, Walker JE (2011) Binding of the inhibitor protein IF1 to bovine F1-ATPase. J Mol Biol 406:443–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardner NW, Monroe LK, Kihara D, Park C (2016) Energetic coupling between ligand binding and dimerization in Escherichia coli phosphoglycerate mutase. Biochemistry 55:1711–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gloss LM, Matthews CR (1997) Urea and thermal equilibrium denaturation studies on the dimerization domain of Escherichia coli Trp repressor. Biochemistry 36:5612–5623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallam AL, Jackson SE (2005) Folding studies on a knotted protein. J Mol Biol 346:1409–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guidry JJ, Moczygemba CK, Steede NK, Landry SJ, Wittung-Stafshede P (2000) Reversible denaturation of oligomeric human chaperonin 10: Denatured state depends on chemical denaturant. Protein Sci 9:2109–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simler BR, Doyle BL, Matthews CR (2004) Zinc binding drives the folding and association of the homo-trimeric gamma-carbonic anhydrase from Methanosarcina thermophila. Protein Eng Des Sel 17:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouslin W, Frank GD, Broge CW (1995) Content and binding characteristics of the mitochondrial ATPase inhibitor, IF1, in the tissues of several slow and fast heart-rate homeothermic species and in two poikilotherms. J Bioenerg Biomembr 27:117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholls DG, Ferguson SJ (2013) Bioenergetics 4 (Academic, Cambridge, MA: ). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung DW, Panzeter E, Baysal K, Brierley GP (1997) On the relationship between matrix free Mg2+ concentration and total Mg2+ in heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1320:310–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donoso P, Mill JG, O’Neill SC, Eisner DA (1992) Fluorescence measurements of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial sodium concentration in rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 448:493–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denton RM, McCormack JG (1980) On the role of the calcium transport cycle in heart and other mammalian mitochondria. FEBS Lett 119:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Gómez-Puyou MT, Gavilanes M, Gómez-Puyou A, Ernster L (1980) Control of activity states of heart mitochondrial ATPase. Role of the proton-motive force and Ca2+. Biochim Biophys Acta 592:396–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.