Abstract

Pineapple peel is a potential feedstock for the extraction of essential oil due to the presence of aromatic compounds. To extract the essential oil from pineapple peels, three different methods were applied, i.e., (1) hydro-distillation (HD); (2) hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted (HDEA); and (3) supercritical fluid extraction (SFE). SFE had successfully produced an essential oil with the yield of 0.17% (w/w) together with 0.64% (w/w) of concrete, whereby the HD and HDEA had only produced hydrosols with the yield of 70.65% (w/w) and 80.65% (w/w), respectively. Parameters’ optimization for HD (substrate to solvent ratio, temperature, and extraction duration) and HDEA (cellulase loading and incubation duration) significantly affected the hydrosol yield, but did not extract out the essential oil. This is because only SFE had successfully ruptured the oil gland after observed under the scanning electron microscope. The essential oil obtained from SFE composed of mainly propanoic acid ethyl ester (40.25%), lactic acid ethyl ester (19.35%), 2-heptanol (15.02%), propanol (8.18%), 3-hexanone (2.60%), and butanoic acid ethyl ester (1.58%). In overall, it can be concluded that the SFE had successfully extracted the essential oil as compared to the HD and HDEA methods.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-019-1767-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Hydro-distillation, Supercritical fluid extraction, Hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted, Essential oil, Pineapple peels

Introduction

Pineapple (Ananas comosus) is a tropical plant originating from East area of South America that grouped under Bromeliaceae family. Despite being consumed as fresh fruit, pineapple also being processed into canned fruit, juice, concentrate, and jam. However, the processing of pineapple produces a considerable high amount of waste, where 30–50% of the total fruit weight is being discarded during processing (Lun et al. 2014). In addition, leaves, stems, and crowns were left behind at the plantation at approximately 2 kg per each tree (MPIB 2017). Due to high transportation cost and limited availability of land area to manage the pineapple wastes, they are mostly being unscrupulously dumped and openly burnt. The current practice of dumping the pineapple wastes can cause microbial spoilage and environmental problems due to high contents of moisture and sugar (Lun et al. 2014). Therefore, the use of pineapple wastes as a low-cost substrate for producing value-added products is considered one of the potential approaches in managing these wastes. Pineapple peels were reported as the largest waste generated during the canning process with a total of 30–42% (w/w) from the total waste (Rattanapoltee and Kaewkannetra 2014). The pineapple peel and leave contain esters (35%), ketones (26%), alcohols (18%), aldehydes (9%), acids (3%), and other compounds (9%) (Barretto et al. 2013). The presence of these compounds indicates that it has the potential to be extracted as an aromatic essence in the form of essential oils.

The essential oil composed of concentrated volatile aromatic compounds that easily evaporated, which give plants their wonderful scents. These highly concentrated substances are found in special cells, glands, or ducts located in various parts of plants such as flowers, leaves, stems, roots, seeds, bark, and resin or fruit rinds (Djilani and Dicko 2012). These oils are often used for their flavour, therapeutic, and odoriferous properties, in various products such as foods, medicines, and cosmetics. Citronella, peppermint, lavender, orange, lime, clove, and eucalyptus are among the major types of essential oils available in the market. Pineapple essential oils are also available in the market, but most of them are in the form of fragrance oil with the combination of natural ingredients and synthetic compounds. It offers a gentle scent of pineapple, where it was widely used in the production of body lotion, bath salts, scented candles, and other various personal care products (Fuller 2016).

Various methods have been developed and employed to extract the essential oil from the plant matrix. Numerous investigations suggested that the yield and chemical composition of essential oil depends on the extraction method (Berka-Zougali et al. 2012). The conventional extraction methods such as hydro-distillation (HD), steam distillation (SD), and cold pressing (CP) are commonly used (Abdul-majeed et al. 2013) due to their simple and cheap extraction setup. Besides, solvent extraction is a method to separate a compound based on the solubility of its parts usually using an organic solvent such as alcohol (Hesham et al. 2016). Although the method is relatively simple and quite efficient, it takes long extraction time, relatively high solvent consumption and usually irreproducibility (Dawidowicz et al. 2008).

In addition, there are also several innovative green extraction methods which have been recently developed to extract essential oil such as microwave-assisted extraction (Cansu et al. 2011), CO2 supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), (Pourmortazavi and Hajimirsadeghi 2007), and enzyme-assisted extraction (Chandran et al. 2012). The recent trend of innovation in extraction methods is developed to meet the demands on the economic perspective, competition among the industries, environmental aspects, sustainability, and good quality of essential oils for industrial production. Enzyme-assisted is a method that using enzyme(s) to treat the sample before the sample being processed in the extraction methods such as HD and SD (Sowbhagya et al. 2011) and tri-solvent extraction (Munde et al. 2017; Ladole et al. 2018). The main function of introducing enzyme-assisted prior to the extraction is to improve the extraction efficiency of bioactive components from the plant matrix. This method involves the use of hydrolytic enzymes to disrupt the cell walls, predominantly composed of highly complex large polymers such as cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin (Boulila et al. 2015). This technique had successfully increased the yield of essential oil from garlic (Sowbhagya et al. 2009), black pepper, and cardamom (Chandran et al. 2012). Meanwhile, the use of supercritical fluids especially carbon dioxide (CO2) in the extraction of plant volatile components has increased as SFE is a fast, effective and virtually solvent-free sample pretreatment technique (Pourmortazavi and Hajimirsadeghi 2007).

Although there are various methods that can be used to extract the essential oil, a feasible method for the extraction of essential oil specifically from pineapple peels is limited. The exploration of the valuable compounds in the pineapple peels might be beneficial for the future application. Therefore, three extraction methods (1) hydro-distillation (HD); (2) hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted pretreatment (HDEA); and (3) supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) were investigated. The HD method was reported to be the simplest and common method in the area of essential oil extraction (Hamzah et al. 2014). Meanwhile, as pineapple peels are material rich in lignocellulosic components such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (Choonut et al. 2014), an enzymatic pretreatment using cellulase was conducted prior to the HD. The SFE was selected as this technique is an advanced method, which technically has the capability to extract valuable botanical constituents (Sapkale et al. 2010; Janghel et al. 2015).

Materials and methods

Preparation of substrate

Pineapple peels were collected from Ladang Nanas, Sg Telur, Kota Tinggi Johor, Malaysia. The peels were cut into small slice and ground using a blender, followed by oven drying at 60 °C for 48 h (Hassanpouraghdam et al. 2010). The ground dried peels were stored in an air-tight container at room temperature.

Extraction of essential oil

Hydro-distillation

A volume of 300 mL of distilled water was added into the 1-L round bottom flask containing 100 g of ground dried pineapple peels. The round bottom flask was connected to the Clevenger-type apparatus. The temperature was set at 100 °C and the HD process was conducted for 3 h (Abdul-Majeed et al. 2013). Once the process was completed, the extract in the trap was collected and the yield was calculated and expressed as a percentage in (w/w). All the samples were stored in the amber airtight sealed vials at − 20 °C until required for further analysis.

Hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted

A total of 100 g of ground-dried pineapple peels were mixed with 100 mL of 0.1 M acetate buffer, pH 5.0 in a 250-mL shake flask. A commercial cellulase (Acremonium Cellulase, Japan) solution at different enzyme loadings of 10–30 FPU/g-substrate was added into the solution mixture. The mixture was incubated at 50 ± 2 °C, 200 rpm for 90 min (Sowbhagya et al. 2009). The sample was filtered using a plastic sieve and stored in the amber airtight sealed vials at − 20 °C prior to HD procedures.

Supercritical fluid extraction

The SFE was conducted using SC–CO2 extraction apparatus (DEVEN Supercritical, Pvt Ltd, India). Approximately, 300 g of ground-dried pineapple peels were placed in the 1-L capacity extractor. CO2 liquid from the cylinder was passed through a chiller at 5 °C to maintain its liquid state. Then, the compressed CO2 was pumped into the extractor at the pressure of 180 bar and a temperature of 50 °C. A static period of 2 h was used to allow contact between the sample and supercritical solvent (CO2), followed by a dynamic extraction for 1 h (Kamali et al. 2015). After the extraction, the essential oil and CO2 mixture was expanded to atmospheric pressure in the separator. CO2 was released into the air, while the extracted oil, wax, and solid residue were collected. All samples were stored in the amber airtight sealed vials at − 20 °C until required for further analysis.

Determination of volatile compounds

The volatile compounds of hydrosols and essential oils obtained through HD, HDEA, and SFE were analyzed using Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 Ultra gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) (Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a BPX-5 column of 30 m length, 0.25 mm i.d., and 0.25 μm film thickness. The injector temperature was set at 250 °C, oven temperature at 50 °C raised to 300 °C at the rate of 3 °C/min, with detector temperature set at 250 °C (Sowbhagya et al. 2009). The ion source temperature was set at 200 °C. A 1 µL of the diluted hydrosol and essential oil (1:100 in methanol, v/v) was transferred in a vial and place on the autosampler (Mothana et al. 2013). The automatic injection was carried out once the instrument is ready. The identification of the compounds was achieved by comparison of their mass spectral fragmentation patterns with those stored in MS Library, which are NIST11, WILEY229, and FFNSC1.3.

Determination of yield

The extract in the trap was collected and the yield was calculated and expressed as a percentage (w/w) as provided in Eq. 1 (Furtado et al. 2018). The oil was stored in the amber airtight sealed vials at 0 °C until required for further analysis:

| 1 |

Scanning electron microscope

The fresh pineapple peels and the solid residue obtained after the extraction process were observed under a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi SU1510, by Hitachi High-Technologies, America). The samples were coated with gold by a sputtering process using Hitachi E-1010 Ion Sputter, then proceed for microscopic observation using 15 kV with working distance range from 4.2 to 6.0 mm (Chandran et al. 2012).

Statistical data analysis

The data were statistically analysed using software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, USA). Multiple comparisons were conducted using Tukey test and differences of (p < 0.05) were considered significant.

Results and discussion

Extraction output

The essential oil was successfully extracted from pineapple peels using SFE with a total yield of 0.17% (w/w) (Table 1). Interestingly, the extraction using SFE also produced 0.64% (w/w) of concrete (also known as solid wax) with the potential of being converted to absolute. Concrete contains fragrance-related compounds like terpenes and sequi-terpenes, fatty acids and their methyl esters, paraffin, and other high molecular weight compounds. This waxy mass is primarily used for the production of absolute, but also commonly used in natural perfumery, solid perfume, and cosmetics. The absolute in the form of waxy-free concentrated natural fragrance can be produced from the concrete through the ethanol extraction method (Baydar et al. 2011).

Table 1.

The extraction output for hydro-distillation, hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted and supercritical fluid extraction

| Method | Output | Yield (% w/w) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| HD | Hydrosol | 70.65 |

Clear in colour Mild pineapple smell Watery texture |

| HDEA | Hydrosol | 80.65 |

Clear in colour Mild pineapple smell Watery texture Emulsion formed on the surface of hydrosol |

| SFE | Essential oil | 0.17 |

Pale yellow in colour Strong pineapple smell Slight oily texture |

| Concrete | 0.64 |

Light to dark yellow in colour Strong pineapple smell (stronger than essential oil) Oily and waxy solid texture |

The extraction using HD and HDEA produced hydrosol instead of essential oil with a yield of 70.65% (w/w) and 80.65% (w/w), respectively. This hydrosol has a mild pineapple smell, contributed by the presence of several volatile compounds. During the distillation of aromatic plants, a small hydrophilic fraction of the essential oil escapes into the distillation water stream, producing hydrosol containing dissolved essential oil components (Rao 2013). In this present study, the emulsion layer formed by several tiny droplets of oils was observed on the top of hydrosol produced through the HDEA method, hence indicates the potential of essential oil recovery from the pineapple peels.

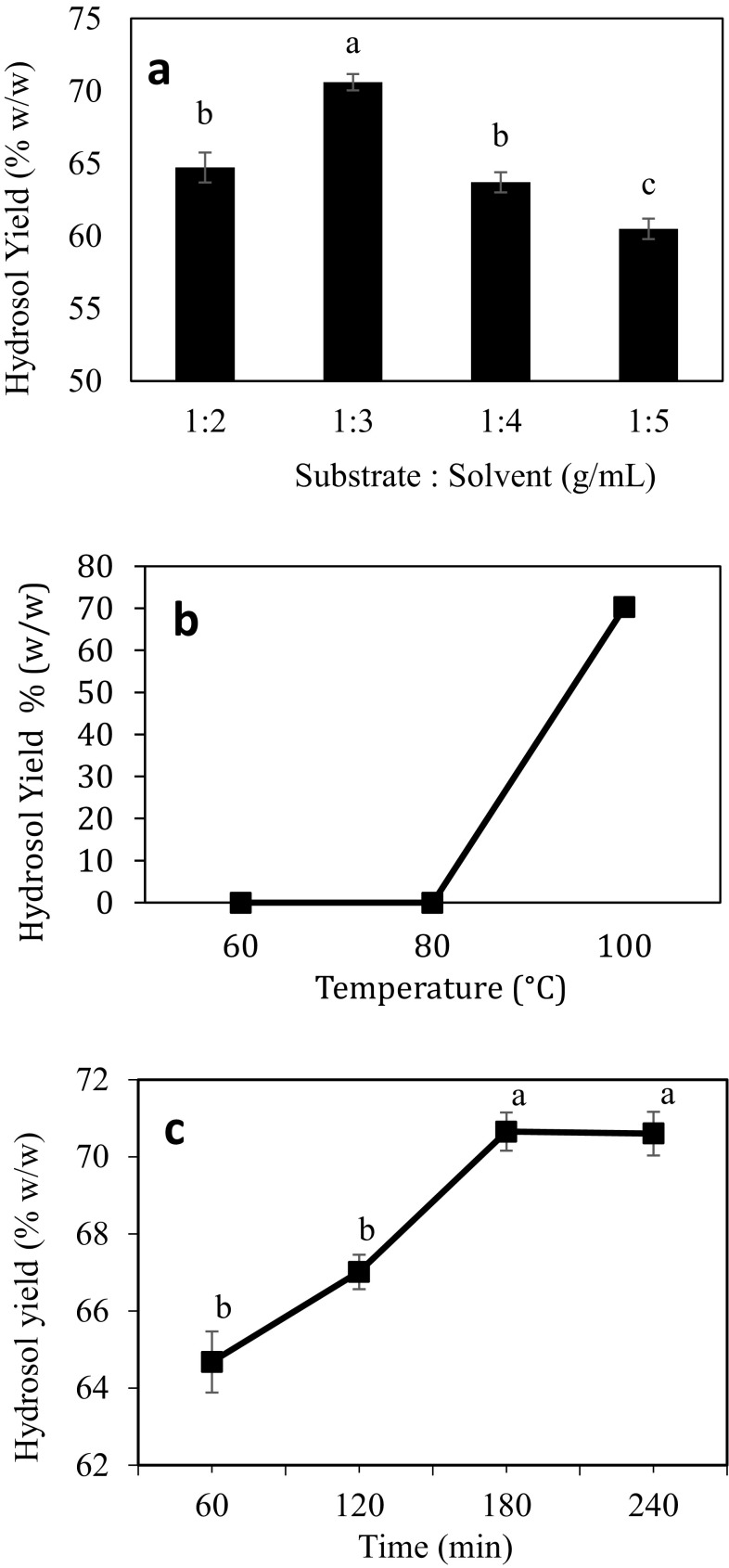

As an attempt to obtain the essential oil through HD and HDEA, several experiments have been conducted to determine the optimal process parameters for both methods, i.e. substrate to solvent ratio, extraction temperature, extraction time, enzyme loading, and incubation time. The results for each process parameters were presented in Figs. 1a–c and 2a, b. Although several parameters have been manipulated, there is no apparent production of essential oil was recorded. However, the process had significantly affected the production of hydrosol.

Fig. 1.

Effect of a substrate-to-solvent ratio, b temperature, and c extraction duration on the hydrosol yield obtained through hydro-distillation of pineapple peels. Values with the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05)

Fig. 2.

Effect of a enzyme loading and b incubation time on the hydrosol yield obtained through hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted of pineapple peels. Values with the same letter are not significantly different (p < 0.05)

HD with the process parameters of 1:3 (g/mL) of substrate to solvent ratio, extraction temperature of 100 °C and 180 min of extraction time produced the highest amount of hydrosol from pineapple peels. It was observed that the hydrosol yield was initially increased up to 70.60 ± 0.57% (w/w) when the substrate-to-solvent ratio increased from 1:2 to 1:3 (g/mL), as shown in Fig. 1a. However, a higher solvent ratio of 1:4–1:5 resulted in the reduction of hydrosol yield might be due to the low concentration of ester compound available after the reaction. Essential oil and hydrosol constituted of mostly esters which give them a pleasant smell. In the presence of water especially at a high temperature, the esters tend to react with water to form acids and alcohols. Therefore, a higher amount of water increases the tendency of acids and alcohols formation, which reduce the hydrosol yield. On the other hand, insufficient amount of water may cause the substrate materials to be overheated and charred (Abdul-majeed et al. 2013).

The hydrosol was formed only at the temperature of 100 °C with the yield of 70.25 ± 0.35% (w/w), as shown in Fig. 1b. The vaporization of essential oil and hydrosol could not occur at the temperature below than that (60 and 80 °C). Meanwhile, extraction temperature of more than 100 °C can cause chemical modifications of the oil components, which resulted in the loss of most of the volatile compounds (Farimani et al. 2017). To allow a longer exposure to the distillation process, the distillation duration was expanded to 240 min. Results showed that the extraction duration from 60 to 180 min had increased the hydrosol yield from 64.68 ± 0.80% (w/w) to 70.65 ± 0.49% (w/w). However, after 180 min of extraction, the hydrosol yield remained constant (Fig. 1c), as it reached equilibrium. However, prolong the extraction also does not resulted in the formation of essential oil. Different constituents of distilled essential oil are based on the order of their boiling points and degree of solubility in water (Yalavarthi and Thiruvengadarajan 2013), which may cause the formation of essential oil extracted from pineapple peel was failed.

To extract the essential oil from the pineapple peels, the HDEA method was conducted by adding cellulase to break down the cell wall of the pineapple peels to release out the essential oil. The cellulase loading was varied from 0 to 30 FPU/g and incubated for 60–150 min. However, the results showed that adding the cellulase and prolonging the incubation time were not able to release out the essential oil, but significantly improved the hydrosol yield. The enzyme loading of 10 FPU/g with an incubation time of 90 min was found to produce the highest hydrosol. The cellulase helped in breaking down the cellular structures to obtain a greater permeability of the cell wall, so the higher yield of essential oil will be produced if a higher amount of enzyme was loaded. However, although the cellulase activity was increased from 10 to 30 FPU/g, no essential oil could be recovered. This situation might be due to the cellulase used in this study is not capable to break down the oil gland layer inside the pineapple peels. The enzyme efficiency with respect to the release of essential oil was reflected by the differences in the structures and properties of the plant materials (Hosni et al. 2013). According to Svobodo and Svobodo (2001) and Gaspar et al. (2001), the presence of toughened cuticle covering completely the rosemary oil gland becomes the major resistance. In contrast, thyme oil gland was characterized by a thin and porous cuticle (Bruni and Modenesi 1983), which easily digested to release out the essential oil.

Volatile compound analysis

The hydrosol obtained after HD and HDEA, as well as the essential oil obtained after SFE were analysed using GC–MS to determine the compositions of volatile compounds. The essential oil obtained through SFE composed of 41 compounds representing 97.33% of the essential oil where the majority of them were esters, alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones. The propanoic acid ethyl ester was present in the highest composition in the essential oil from pineapple peels obtained in this study (40.25%). This ester compound is among the most common compounds identified in other essential oils (Bassole et al. 2003). It was also reported as an important compound to citrus fruit flavour, together with ethyl acetate, methyl butyrate, ethyl butyrate, and ethyl butanoate (Sawamura 2010). Another abundant compound detected in this pineapple peels essential oil is lactic acid ethyl ester (19.35%), which is a monobasic ester formed from the reaction between lactic acid with ethanol. It can be found naturally in various types of fruit. This compound was also found in other fruits and flowers essential oil and distillate such as melon (Hernandez-Gomez et al. 2005) and koumaria (Soufleros et al. 2005).

The essential oil from pineapple peels that was extracted through SFE method also contains the common compounds that can be found in pineapple. The presence of propanoic acid ethyl ester, benzaldehyde, 1-pentanol, 1-octanol, diethyl succinate, and furfural in the pineapple peels essential oil obtained in this study were also found in the pineapple processing residues distillate (Barretto et al. 2013). Besides that, propanoic acid ethyl ester, 1-pentanol, benzaldehyde, diethyl succinate, and 2(3H)-furanone were also identified in home-made pineapple juice and commercial pineapple water (Elss et al. 2005).

In comparison with the commercial pineapple essential oil, only four identical compounds were identified as of in the pineapple peels essential oil extracted through SFE (Table 2). The essential oil obtained through SFE composed mainly esters, alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones. In general, essential oils contain a mixture of the volatile fraction (aldehydes, alcohol, esters, and hydrocarbons) and non-volatile residue (fatty acids, sterols, carotenoids, waxes, and flavonoids (Jing et al. 2014). Based on the GC–MS analysis on the commercial pineapple essential oil, it was found that this commercial product composed mainly of isopropyl palmitate (69.88%), which is a palm-oil derivative that commonly used as a thickening agent in the skincare products. A trace of tripropylene glycol (3.26%) was also identified with the ability to bind and carry the fragrance elements.

Table 2.

Similar compounds presence in pineapple peels essential oil as compared to commercial pineapple essential oil

| No | Compound | Composition (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pineapple peels essential oil from SFE | Commercial pineapple essential oil | ||

| 1 | Butanoic acid ethyl ester | 1.58 | 0.23 |

| 2 | 1-Pentanol | 1.91 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 2-Ethyl butyric acid | 0.13 | 0.28 |

| 4 | 2,3-Dihydro-5-methyl-2-furanone | 0.22 | 1.24 |

After the HD extraction, a total of 8 major compounds representing 25% of the hydrosol composition were identified by GC–MS, as shown in Table 3. It was reported that hydrosol contains some amounts of essential oil that may escape during the distillation process that contains water-soluble components of aromatic plants in addition to essential oil constituents.

Table 3.

Major volatile compounds identified in the hydrosol obtained through the hydro-distillation method

| Retention time (min) | Composition (%) | Compound name |

|---|---|---|

| 4.63 | 2.56 | Glycine |

| 4.95 | 5.75 | Acetic acid |

| 5.47 | 2.36 | Dimethylsilanediol |

| 33.01 | 1.35 | Stigmasterol |

| 33.97 | 4.32 | Ethyl iso-allocholate |

| 34.25 | 2.38 | 1-Heptatriacotanol |

| 36.33 | 1.08 | Oleic acid |

| 39.22 | 4.66 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid |

Similar to HD, HDEA extraction method also produced hydrosol that contained a total of nine compounds representing 70% of the hydrosol composition (Table 4). The major compounds in this hydrosol were Z-9-pentadecenol (15.60%), oleic acid (13.71%), and ethyl iso-allocholate (13.48%). There are several identical compounds as detected in the hydrosol from HD extraction such as oleic acid, 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid, and ethyl iso-allocholate. HDEA involves the use of hydrolytic enzymes (i.e., cellulase) to disrupt the cell walls of the pineapple peels, which predominantly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin (Choonut et al. 2014), thus enabling the better release of essential oil (Puri et al. 2012). This method has been reported to successfully increase essential oil yield and quality from garlic (Sowbhagya et al. 2009), black pepper, and cardamom (Chandran et al. 2012).

Table 4.

Major volatile compounds identified in the hydrosol obtained through hydro-distillation with the enzyme-assisted method

| Retention time (min) | Composition (%) | Compound name |

|---|---|---|

| 3.60 | 3.19 | Hexamethydisiloxane |

| 4.35 | 2.05 | 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester |

| 4.69 | 5.00 | Acetic acid |

| 37.12 | 3.86 | Cyclopropanebutanoic acid |

| 37.94 | 3.24 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid |

| 39.99 | 15.60 | Z-9-Pentadecenol |

| 43.60 | 13.71 | Oleic acid |

| 43.84 | 13.48 | Ethyl iso-allocholate |

| 45.51 | 9.96 | 1-Heptatriacotanol |

This GC–MS analysis showed that hydrosol has the potential to be used in a similar application as an essential oil. However, up to date, there is no legal definition of hydrosol and its grade, no specifications and standards of use for various applications such as aromatherapy, food, cosmetics, and other uses. Despite hydrosol’s popularity gained nowadays, research efforts to address related issue need to be carried out extensively to project hydrosols as scientifically acceptable, safe, efficient, stable, and affordable commercial products (Rao 2013).

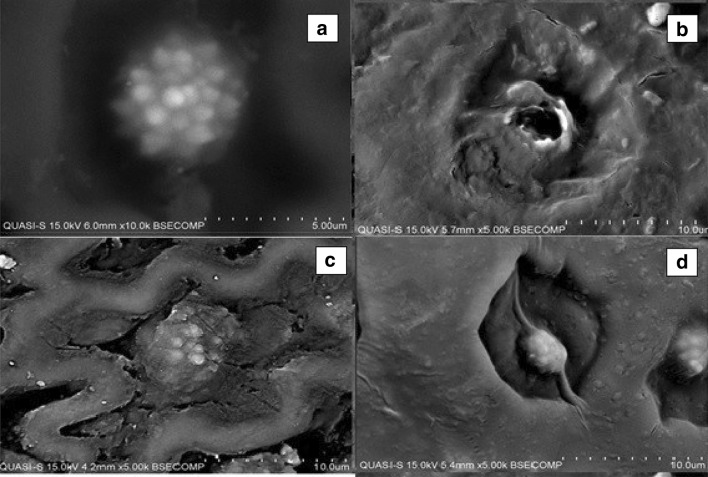

Cell-wall observation using SEM

The solid samples obtained after HD, HDEA and SFE were examined under SEM in comparison to a fresh sample of pineapple peels. It was observed that the secretory structures or glands were evenly distributed on the surface of the fresh peels (Fig. 3a). The glands are spherical in shape and placed in an individual cavity surrounded by the plant tissue. These secretory structures commonly stored the secretion materials like salts, latex, waxes, fats, flavonoids, gums, mucilages, resin and also essential oil (Svobodo and Svobodo 2001).

Fig. 3.

SEM image of pineapple peels for a fresh and after each extraction, b supercritical fluid, c hydro-distillation, and d hydro-distillation with enzyme-assisted (5.00–10.0 k magnification, 15 kV, 4.2–6.00 mm working distance

After the HD extraction, it was observed that the glands were swollen and the tissue between the glands was structurally expended. However, there was no sign of destroyed glands (Fig. 3c). The glands structures were maintained at their original shape even though they were swollen, hence, indicated that no secretion of essential oil happened during the extraction. This image reflected the extraction results where no essential oil was produced through the HD method. The HD method was carried out at atmospheric pressure, 1 atm and using water as a solvent. Although with a combination of high extraction temperature, it was observed that the structure of the glands containing essential oil was remained undestroyed, thus releasing no essential oil. Immersing the pineapple peels in the water during HD extraction was aimed to open the structure of the gland. At the temperature of boiling water, a part of volatile oil dissolves in the water present inside the glands. This oil–water solution permeates by osmosis to reach the outer surface of the gland, which caused the gland to became swollen (Pangarkar 2008). However, it was inferred that, due to the absence of external pressure, the swollen glands were unable to rupture, thus gave no apparent effect on the release of essential oil.

The SEM image of the solid residue obtained after HDEA showed that the oil glands become deflated and shrank (Fig. 3d), but they were not ruptured. The changes in the oil glands structure prompted that the secretion of materials from the gland occurred. The release of compounds from the oil glands after HDEA extraction was incomplete therefore leaving the oil glands at their original position. This condition reflected the final observation where no essential oil can be obtained after the HDEA extraction. The enzyme efficiency with respect to the release of essential oil was reflected by the differences in the structures and properties of the plant materials (Hosni et al. 2013). According to Svobodo and Svobodo (2001) and Gaspar et al. (2001), the presence of toughened cuticle covering completely the rosemary oil gland presents the major resistance for the release of essential oil. In contrast, thyme oil gland was characterized by a thin and porous cuticle, making the release of essential oil easier (Bruni and Modenesi 1983).

On the other hand, the oil glands were ruptured and destroyed after undergone SFE extraction (Fig. 3b). Some of the glands were totally removed, leaving many holes. This observation reflected the successful extraction of essential oil after the SFE extraction. The rupture of oil glands after SFE due to the contribution of CO2 behaviour. In SFE, CO2 was used as a supercritical solvent, which is neither in liquid nor gas condition. The liquid-like densities of the supercritical CO2 lead to superior mass transfer distinctiveness that enables the easy release of the solute. This uniqueness is owed to the high diffusion and very low surface tension of the supercritical fluid that enables easy infiltration into the permeable make-up of the solid matrix to reach the solute (Janghel et al. 2015). The pressure and temperature together with the supercritical CO2 behaviour as a solvent was induced and caused the oil gland to be under great thermal stress. The pressure build-up within the glands could have exceeded their capacity for expansion, thus leading to the rupture of the gland (Golmakani and Moayyedi 2015) and releasing the essential oil.

Conclusions

SFE had successfully produced the essential oil from pineapple peels with 0.17% (w/w) yield, together with 0.64% (w/w) of concrete. On the other hand, hydrosol with the yield of 70.65% (w/w) and 80.65% (w/w), respectively, was obtained through HD and HDEA methods. The GC–MS analysis showed that the essential oil produced through SFE mainly composed of esters, alcohols, aldehydes, and ketones, which are similar to the compounds detected in commercial pineapple essential oil. Meanwhile, the hydrosol from HD and HDEA extraction contains some important volatile compounds, hence has the potential to be used in the similar application of essential oil. In addition to that, the cell-wall observation using SEM supported the outcome from each extraction method, whereby only the SFE method resulted in the rupture of essential oil glands, thus releasing the essential oil. As a conclusion, SFE was found as a feasible method to extract the essential oil from pineapple peels, whereas HD and HDEA methods only produced a hydrosol.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This research work was supported by Geran Putra IPM, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM) (vote no 9435100), Graduate Research Fellowship (GRF) from UPM, MyBrains scholarship from Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Malaysia and Alaf Putra Biowealth Sdn Bhd.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdul-majeed BA, Hassan AA, Kurji BM. Extraction of oil from Eucalyptus camadulensis using water distillation method. Iraqi J Chem Pet Eng. 2013;14(2):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Barretto LC, Moreira JD, Santos JA, Narendra N, Santos RA. Characterization and extraction of volatile compounds from pineapple (Ananas comosus L. Merril) processing residues. Food Sci Technol. 2013;2013(006010):638–645. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612013000400007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bassole IHN, Ouattara AS, Nebie R, Ouattara CAT, Kabore ZI. Chemical composition and antibacterial activities of the essential oils of Lippia chevalieri and Lippia multiflora from Burkina Faso. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:209–212. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00477-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar H, Sangun MK, Erbas S, Kara N. Comparison of aroma compounds in distilled and extracted products of sage (salvia officinalis L.) J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2011;16:39–44. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2013.764175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berka-Zougali B, Ferhat M-A, Hassani A, Chemat F, Allaf KS. Comparative study of essential oils extracted from Algerian Myrtus communis L. leaves using microwaves and hydrodistillation. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(12):4673–4695. doi: 10.3390/ijms13044673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulila A, Hassen I, Haouari L, Mejri F, Amor IB, Casabianca H, Hosni K. Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from bay leaves (Laurus nobilis L.) Ind Crops Prod. 2015;74:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.05.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni A, Modenesi P. Development, oil storage and dehiscence of peltate trichomes in Thymus vulgaris (Lamiaceae) Nordic J Bot. 1983;3(2):245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.1983.tb01073.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cansu TB, Yocel M, Sinex K, Baltact C, Karaoglu SA, Yayli N. Microwave assisted essential oil analysis and antimicrobial activity of M. alpestris subsp. alpestris. Asian J Chem. 2011;23(3):1029–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Chandran J, Amma KPP, Menon N, Purushothaman J, Nisha P. Effect of enzyme assisted extraction on quality and yield of volatile oil from black pepper and cardamom. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2012;21(6):1611–1617. doi: 10.1007/s10068-012-0214-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choonut A, Saejong M, Sangkharak K. Energy procedia. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2014. The production of ethanol and hydrogen from pineapple peel by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Enterobacter aerogenes; pp. 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Dawidowicz AL, Rado E, Wianowska D, Mardarowicz M, Gawdzik J. Application of PLE for the determination of essential oil components from Thymus vulgaris L. Talanta. 2008;76(4):878–884. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djilani A, Dicko A (2012) The therapeutic benefits of essential oils. In: Bouayed J (ed) Nutrition, well-being and health. IntechOpen, pp 155–167 (ISBN: 978-953-51-0125-3)

- Elss S, Preston C, Hertzig C, Heckel F, Richling E, Schreier PÃ. Aroma profiles of pineapple fruit (Ananas comosus L Merr.) and pineapple products. LWT Food Sci Technol. 2005;38(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2004.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller J (2016). Pineapple essential oil benefits. https://foryourmassageneeds.com. Accessed 18 Jul 2018

- Furtado FB, Borges BC, Teixeira TL. Chemical composition and bioactivity of essential oil from blepharocalyx salicifolius. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(33):1–13. doi: 10.3390/ijms19010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar F, Santos R, King MB. Disruption of glandular trichomes with compressed CO2. J Supercrit Fluids. 2001;21(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/S0896-8446(01)00073-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golmakani M, Moayyedi M. Comparison of heat and mass transfer of different assisted extraction methods of essential oil from Citrus limon (Lisbon variety) peel. Food Sci Nutr. 2015;3(6):506–518. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamzah MH, Hasfalina CM, Zurina ZA, Hishamuddin J. Comparison of citronella oil extraction methods from Cymbopogon nardus grass by ohmic-heated hydro-distillation, hydro-distillation, and steam distillation. BioResources. 2014;9:256–272. doi: 10.15376/biores.9.1.256-272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanpouraghdam MB, Abbas H, Farsad-Akhtar N, Lamia V. Drying method affects essential oil content and composition of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) J Essent Oil Bear Plants JEOP. 2010;6:759–766. doi: 10.1080/0972060X.2010.10643892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Gomez LF, Ubeda-iranzo J, Garcia-Romero E, Brinoes-Perez A. Food chemistry comparative production of different melon distillates: chemical and sensory analyses. Food Chem. 2005;90:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.03.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rassem HH, Nour AH, Yunus RM. Techniques for extraction of essential oils from plants: a review. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 2016;10:117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hosni K, Hassen I, Chaâbane H, Jemli M, Dallali S, Sebei H, Casabianca H. Enzyme-assisted extraction of essential oils from thyme (Thymus capitatus L.) and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): impact on yield, chemical composition and antimicrobial activity. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;47:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Janghel A, Deo S, Raut P, Bhosle D, Verma C, Kumar SS, et al. Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) techniques as an innovative green technologies. Res J Pharm Technol. 2015;8(6):775–786. doi: 10.5958/0974-360X.2015.00125.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jing L, Zhentian L, Li L, Xie R, Xi W, Guan Y, et al. Antifungal activity of citrus essential oils. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;14(62):3011–3033. doi: 10.1021/jf5006148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamali H, Aminimoghadamfarouj N, Golmakani E, Nematollahi A. The optimization of essential oils supercritical CO2 extraction from lavandula hybrida through static-dynamic steps procedure and semi-continuous technique using response surface method. Pharmacogn Res. 2015;1(7):57–65. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.147209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladole M, Nair R, Bhutada Y, Amritkar V, Pandit A. Synergistic effect of ultrasonication and co-immobilized enzymes on tomato peels for lycopene extraction. Ultrason Sonochem. 2018;48:453–462. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun OK, Wai TB, Ling LS. Pineapple cannery waste as a potential substrate for microbial biotranformation to produce vanillic acid and vanillin. Int Food Research J. 2014;21(3):953–958. [Google Scholar]

- Moridi Farimani M, Mirzania F, Sonboli A, Moghaddam FM. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of Dracocephalum kotschyi essential oil obtained by microwave extraction and hydrodistillation. Int J Food Prop. 2017;20(1):306–315. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2017.1295987. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mothana RA, Al-said MS, Al-yahya MA, Al-rehaily AJ. GC and GC/MS Analysis of essential oil composition of the endemic soqotraen leucas virgata balf. f. and its antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;0067(14):23129–23139. doi: 10.3390/ijms141123129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MPIB (2017) Jumlah pengeluaran sisa ladang nanas semenanjung Malaysia 2014–2017

- Munde PJ, Muley AB, Ladole MR, Pawar AV, Talib MI, Parate VR. Optimization of pectinase-assisted and tri-solvent-mediated extraction and recovery of lycopene from waste tomato peels. 3 Biotech. 2017;3(7):206. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0825-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pangarkar VG. Microdistillation, thermomicrodistillation and molecular distillation techniques. In: Handa SS, Khanuja SPS, Gennaro L, Rakesh DD, editors. Extraction technologies for medicinal and aromatic plants. Trieste: ICS-UNIDO; 2008. pp. 21–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pourmortazavi SM, Hajimirsadeghi SS. Supercritical fluid extraction in plant essential and volatile oil analysis. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1163(1–2):2–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri M, Sharma D, Barrow CJ. Enzyme-assisted extraction of bioactives from plants. Trends Biotechnol. 2012;30(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao BRR. Hydrosols and water-soluble essential oils: medicinal and biological properties. In: Govil JN, Sanjib B, editors. Recent Progress in medicinal plants essential oils 1. New York: India: Studium Press LLC; 2013. pp. 120–140. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanapoltee P, Kaewkannetra P. Utilization of agricultural residues of pineapple peels and sugarcane bagasse as cost-saving raw materials in scenedesmus acutus for lipid accumulation and biodiesel production. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;173(6):1495–1510. doi: 10.1007/s12010-014-0949-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapkale GN, Patil SM, Surwase US, Bhatbhage PK. A review:supercritical fluid extraction. Int J Chem Sci. 2010;8(2):729–743. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura M. Citrus essential oils flavor and fragrance. New York: Kochi University, Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Soufleros EHÃ, Mygdalia SA, Natskoulis P. Production process and characterization of the traditional Greek fruit distillate “Koumaro” by aromatic and mineral composition. J Food Compos Anal. 2005;18:699–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2004.06.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowbhagya HB, Purnima KT, Florence SP, Appu Rao AG, Srinivas P. Evaluation of enzyme-assisted extraction on quality of garlic volatile oil. Food Chem. 2009;113(4):1234–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.08.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sowbhagya HB, Srinivas P, Purnima KT, Krishnamurthy N. Enzyme-assisted extraction of volatiles from cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.) seeds. Food Chem. 2011;127(4):1856–1861. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svobodo KP, Svobodo TG. Secretory Structures of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants: A Review and Atlas of Micrographs. (M. S. Polly, Ed.) Microscopix, 2000. 2001 doi: 10.1016/S0962-4562(00)80017-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yalavarthi C, Thiruvengadarajan VS. A review on identification strategy of phyto constituents present in herbal plants. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2013;4(2):123–140. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.