Abstract

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) – with daily emtricitabine-tenofovir – has been demonstrated to be a safe and effective method of reducing HIV incidence. Questions remain regarding PrEP’s efficacy and outcomes in real-world clinical settings. We conducted a retrospective review to assess PrEP outcomes in an academic clinic setting and focused on retention in care, reasons for discontinuation, and receipt of appropriate preventative care (immunizations, HIV testing, and STI testing). 134 patients were seen between 2010–2016 over 309 visits. 116 patients (87%) started daily PrEP and of those, 88 (76%) attended at least one 6-month follow-up visit. Over 60% of PrEP patients completed all recommended STI screening after starting PrEP. Only 40% of patients had all appropriate immunizations at baseline; 78% had all appropriate immunizations at study completion. This study demonstrated high rates of both retention and of attaining recommended preventative care in a clinical setting outside of the rigors of clinical trials.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, prevention, real world clinic setting, preventative care

In the US, approximately 40,000 individuals are diagnosed with HIV every year with an overall prevalence of around 1.1 million people (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with Emtricitabine/Tenofovir (Truvada) was approved by the FDA in 2012 and has been shown to be safe and effective in reducing HIV incidence in multiple at-risk populations (Grant et al., 2010). Multiple trials have demonstrated PrEP’s efficacy at greater than 90% when patients were adherent to the regimen (Grant et al., 2010; Baeten et al., 2012). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 1.2 million American adults meet eligibility criteria for PrEP (Smith et al., 2015).

As expected, most PrEP studies have been performed in tightly regulated research settings with few trials evaluating PrEP in a “real-world” clinical setting. In the research environment, it is likely that follow-up and adherence is higher since study visits are frequent, study staff are charged with retaining research subjects, PrEP medication is given directly to participants, and compensation is given to subjects for study completion.

For example, the US PrEP Demonstration Project had a high retention rate, with 78% remaining in the study at one year (Liu et al., 2016). However, the circumstances of this project may not represent those found in typical clinical settings, as patients received PrEP at no cost. A report on a large cohort of patients who were Kaiser Permanente Northern California members had only a 23% discontinuation rate during the 3-year study (Marcus et al., 2016). Although patients in this cohort were not enrolled in a PrEP study protocol, their discontinuation rates may be lower than expected elsewhere due to Kaiser’s unique, innovative prescribing protocol (Marcus et al., 2016). Kaiser’s protocol has a low logistical burden on patients to continue PrEP by not requiring in-person follow-up visits and by providing telemedicine adherence support, conditions not found in most health systems (Marcus et al., 2016). In typical clinical settings, medication costs and insurance navigation can also be major barriers. Chan and colleagues found in their report of PrEP use in 3 sites in 3 US cities that PrEP retention rates were 73% at 3 months and 60% at 6 months (Chan et al., 2016). Another recent PrEP study of 50 patients in a Providence-based STD clinic demonstrated only 62% retention at 3 months and 38% retention at 6 months (Montgomery et al., 2016). In these studies, reasons for loss in retention included low HIV perception risk, side effect concerns, and financial barriers.

In addition to issues surrounding continuation of PrEP, some providers have concerns regarding the potential for sexual disinhibition and an increase in sexually-transmitted infections among PrEP users. Multiple survey-based studies have evaluated sexual disinhibition in the setting of PrEP and have presented varied results (Golub, Kowalczyk, Weinberger, & Parsons, 2010; Whiteside, Harris, Scanlon, Clarkson, & Duffus, 2011). A range of patients surveyed in these trials reported they would use condoms less often if on PrEP, but this behavior has not been fully evaluated in people taking PrEP. A recent study did show potential for behavioral compensation regarding condom use in PrEP users, especially in patients with multiple partners in the previous 3 months (Oldenburg et al., 2017). In the Kaiser cohort, STIs were common at baseline and only increased for 2 of the 7 STIs measured (Marcus et al., 2016). Ongoing education at PrEP follow-up visits may reduce sexual behavioral disinhibition (Baeten et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2010; Marcus et al., 2013).

PrEP visits also provide opportunities to complete preventative healthcare recommendations including immunizations. Many men who have sex with men (MSM) that are eligible for PrEP are also recommended to be screened and immunized for Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV). Integrating these preventative measures with PrEP clinic visits offers the opportunity to close gaps in preventative care in this population, which may not otherwise be integrated into the healthcare system, or which may not receive appropriate preventative recommendations from their health care providers (Petroll and Mosack, 2011; Ng et al., 2014).

The goal of this study was to evaluate PrEP outcomes – including retention in care, adherence to follow-up and HIV and STI testing recommendations, acquisition of STIs, and receipt of recommended preventative healthcare – in a clinical setting, with a focus on all patients who were prescribed PrEP over a 5.5-year period in a clinic in the Midwestern U.S.

Methods

General

We evaluated data from all patients who attended a clinical PrEP program at an academic medical center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin between December 2010 and July 2016. The PrEP program was started within the medical center’s outpatient Infectious Diseases clinic in which more than 800 patients receive care for HIV and where patients are seen for a full spectrum of infectious diseases. The clinic overall conducts about 400 visits per month. PrEP clinic visits were offered during daytime hours by 6 providers within their HIV or general infectious diseases clinics and two evening clinics per month specifically for PrEP patients were held by 3 providers. The clinic is part of the not-for-profit academic medical center and did not receive any funding specifically to provide PrEP.

Per CDC interim guidance, and later per CDC guidelines, patients were recommended to complete provider visits and STI testing every 6 months as well as HIV testing every 3 months via lab visits (Grant et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; US Public Health Service, 2014). Patients received adherence counseling at each clinic visit. Patients were encouraged to utilize the patient portal of the institution’s electronic medical record, which provided appointment reminders for those who opted in; all patients received appointment reminder phone calls. We offered patients enrollment into a medication management program run by pharmacists to assist with navigating insurance and also to monitor for adherence, side effects, and follow-up. For individuals enrolled in the program, information was solicited during monthly phone calls prior to filling the next month’s prescription. Pharmacy staff directly assisted patients with overcoming adherence struggles (e.g. reminders to refill PrEP and regular monitoring of side effects and drug-drug interactions) and navigating insurance coverage barriers to receiving PrEP, and they sent to medical providers any information regarding side effects or other questions. Pharmacy staff also provided reminders to patients regarding 3-month HIV testing intervals if they had not received testing at the required intervals. Patients were referred to the clinic by established patients, local STI clinics, and local community physicians. Some patients found the clinic through Internet searches.

Measures

Data was collected via chart review of patients who made appointments with the PrEP clinic using our institution’s electronic health record. We collected demographic data, including age, gender, race, and sexual orientation and behavioral data, such as number of sexual partners in the past 3 months, type of sexual intercourse (anal insertive, anal receptive, or both), frequency of condom use (always, sometimes, never), and whether the patient was in a serodiscordant relationship. We also reviewed medical history data, including history of STI; number of tests and results of STI testing (Gonorrhea, Chlamydia, Syphilis, HIV, Hepatitis C); treatment of STI; immunization status and serologies if applicable (Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, Human Papillomavirus); and whether each patient had a primary care provider. When assessing whether patients received HIV and STI tests with the recommended frequency (every 3 months for HIV and every 6 months for STIs), a 1-month cushion was allowed (i.e., tests within 4 months for HIV testing and within 7 months for STI screening were included). Using the electronic health record, we also analyzed the number of appointments for each patient; status of each appointment (e.g., completed, no-showed, cancelled); whether PrEP was prescribed; length of time on PrEP (measured in months); reason for discontinuing PrEP (when applicable); participation in the medication management/adherence program; and presence of future scheduled visits. When assessing whether patients attended the recommended number of follow-up appointments (one every 6 months), a 1-month cushion was allowed (i.e., an appointment within 7 months would be included in that 6-month period). Only those that had initiated PrEP at least 6 months prior to data collection, and therefore due for a follow-up visit, were included in retention-in-care analyses. Other data reviewed included referral source, insurance type, and copay amount for PrEP.

Data Analysis

Primary outcomes included retention in the PrEP clinic, meeting optimal PrEP care guidelines (follow-up visits, STI testing, HIV testing), STI rates, and receiving other recommended preventative care. We describe the proportion of PrEP clinic patients who were retained in clinic, met follow-up guidelines, were diagnosed with STIs at baseline and during follow-up, and received recommended preventative care at baseline and during follow-up. Logistic regression was used to explore factors associated with these outcomes. For each primary outcome, we tested each factor for an association with the outcome separately controlling for time on PrEP, and then included those factors associated with the outcome (p < 0.10) in a multiple logistic regression. Throughout the results, we report unstandardized betas, standard errors, and odds ratios. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at [INSTITUTION BLINDED].

Results

One hundred and thirty-nine patients made appointments at the Infectious Diseases clinic at the academic medical center between December 2010 and July 2016. Of the 139 patients who made appointments, 134 (96%) presented to their initial encounter. Of those 134 patients, 116 (87%) were ultimately prescribed PrEP. Eighteen patients were not prescribed PrEP; of these, 9 (50%) decided not to start after their first provider visit, 5 (28%) did not start due to insurance or cost reasons, and 2 (11%) were HIV positive on their initial screen. The 134 patients completed a total of 309 clinic visits between December 2010 and July 2016.

The demographic characteristics of patients attending at least one appointment at the clinic are depicted in Table 1 (n = 134). Of the 134 patients, 131 reported their gender as male and 3 as female. The average age was 37.5 years (range: 19–71 years, median: 35). Most patients (71%) were White, 15% were African American, 7% were Hispanic or Latino, and 7% reported other races (the electronic medical record collects both race and ethnicity within 1 data field). The great majority (95%) identified as MSM. Over one-fifth (22%) were in a relationship with a person who they reported to be HIV-positive. On average, patients had 4.5 sexual partners in the prior 3 months (SD = 4.85). Of 105 patients that stated how they were referred to the PrEP clinic, 26% were referred by a partner or friend who was either HIV positive or already on PrEP, 24% were referred by their primary care provider, 20% were referred by an STI clinic, and 30% found the clinic by other means (primarily self-referral). Table 2 presents primary and secondary outcomes.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics (n=134)

| Category | Characteristic | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 131 | 97.7% | |

| Female | 3 | 2.2% | |

| Age | |||

| 18–29 | 35 | 26.1% | |

| 30–39 | 48 | 35.8% | |

| 40–49 | 30 | 22.3% | |

| 50–59 | 16 | 11.9% | |

| ≥60 | 5 | 3.7% | |

| Average | 37.5 years | ||

| Race | |||

| African American | 20 | 14.9% | |

| White | 96 | 71.6% | |

| Hispanic | 9 | 6.7% | |

| Other | 9 | 6.7% | |

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Bisexual | 6 | 4.4% | |

| Heterosexual | 6 | 4.4% | |

| Homosexual | 122 | 91.0% | |

| Source of Clinic Referral | |||

| Partner/friend | 27 | 20.1% | |

| STI clinic | 22 | 16.4% | |

| Primary care physician | 25 | 18.6% | |

| Self | 10 | 7.4% | |

| Word of mouth | 9 | 6.7% | |

| Internet | 4 | 2.9% | |

| Other | 4 | 2.9% | |

| Unknown | 33 | 24.6% | |

| Insurance | |||

| Public | 26 | 19.4% | |

| Private | 106 | 79.1% | |

| None | 2 | 1.4% |

Patient characteristics and demographics of all patients that attended the PrEP clinic. Other sources of referral included: community talks on PrEP, local HIV clinic, emergency department, and patients who transitioned from PEP to PrEP.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes (n=116)

| Variable | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Started PrEP | 116 | 100.0% |

| Gaps in PrEP use | 6 | 5.2% |

| Attended follow-up | 88 | 75.9% |

| Attended 6-monthly appointments* | 70 | 60.3% |

| Time on PrEP | ||

| <3 months | 11 | 9.5% |

| 3–6 months | 28 | 24.1% |

| 7–12 months | 37 | 31.9% |

| 13–24 months | 33 | 28.5% |

| >2 years | 7 | 6.0% |

| Discontinued PrEP | ||

| Total | 22 | 19.0% |

| Moved away from study city | 7 | 6.0% |

| Side effects | 3 | 2.6% |

| Change in relationship statis | 3 | 2.6% |

| Appropriate HIV testing** | 87 | 75.0% |

| Appropriate STI testing*** | 83 | 71.6% |

| STI at baseline (of tested) | ||

| Gonorrhea Positive (Tested) | 8 (106) | 7.6% (91.4%) |

| Chlamydia Positive (Tested) | 11 (106) | 10.4% (91.4%) |

| Syphilis Positive (Tested) | 5 (110) | 4.6% (94.8%) |

| STI at follow-up (of tested) | ||

| Gonorrhea Positive (Tested) | 7 (64) | 10.9% (55.2%) |

| Chlamydia Positive (Tested) | 16 (64) | 25.0% (55.2%) |

| Syphilis Positive (Tested) | 3 (69) | 4.4% (59.5%) |

| Preventative Healthcare^ | ||

| Vaccinated for Hepatitis A at baseline | 69 | 51.5% |

| Vaccinated for Hepatitis A at follow-up | 106 | 79.1% |

| Vaccinated for Hepatitis B at baseline | 95 | 70.9% |

| Vaccinated for Hepatitis B at follow-up | 117 | 87.3% |

| Vaccinated for HPV at baseline^^ | 3 | 12.5% |

| Vaccinated for HPV at follow-up^^ | 16 | 66.7% |

Primary and secondary outcomes for patients that attended the PrEP Clinic.

denotes that patients attended appointments every 6 months with a 1 month cushion (i.e. 7 months), including only patients on PrEP >6 months.

denotes HIV testing every 3 months.

denotes STI (GC/CT/syphilis) testing every 6 months.

denotes all 134 patients who initially presented to clinic.

denotes all patients under the age of 26 and eligible for HPV vaccination

PrEP Use and Discontinuation

A total of 116 patients started on PrEP and of those, 22 patients discontinued PrEP. The 116 patients that started on PrEP had taken PrEP for between 0 and 55 months, with an average time on PrEP of 11.06 months (SD = 8.25, Median = 9). The 94 patients who did not discontinue PrEP had taken PrEP for between 2 and 40 months, with an average time on PrEP of 11.28 months (SD = 7.19, Median = 10). Seven patients (6%) stopped taking PrEP temporarily but resumed; they were on PrEP between 1 and 13 months prior to this gap (M = 4.86, SD = 4.30, Median = 4).

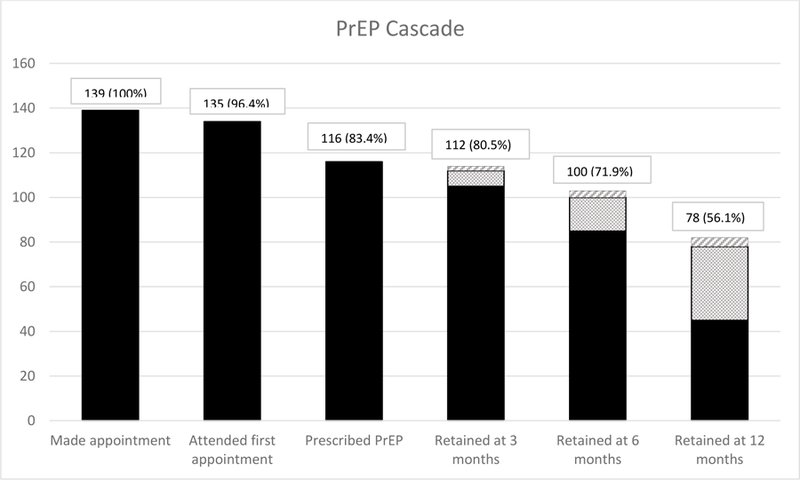

Of the 116 patients who started PrEP, 22 patients (19%) discontinued PrEP use at our clinic. Of these, 8 patients (6%) moved out of the study city, were referred to PrEP clinics elsewhere, and indicated that they planned to continue PrEP. Other reasons for discontinuation included relationship and sex drive factors (e.g., being in a monogamous relationship, n = 3, 14%) and side effects of Truvada (n = 3, 14%). Reasons for discontinuation were unknown for other patients (n = 8, 36%). Side effects reported included nausea (2 patients) and fatigue (1 patient). Before discontinuing, patients had taken PrEP for between 0 and 55 months, with an average time on PrEP of 9.82 months (SD = 11.94, Median = 6.5). There was no evidence that any factors explored were associated with PrEP discontinuation (all ps > 0.16). Figure 1 presents retention in care as a cascade.

Figure 1. PrEP Cascade (n=139).

Demonstrates the PrEP cascade of care beginning when patients made initial contact by scheduling appointments followed by incidence of patients attending their first appointment, patients prescribed PrEP, and patients that retained in care at 3, 6, and 12 months. Dotted sections denotes patients that received PrEP prescriptions at previous follow-up but were not yet due for 3, 6, or 12 month follow-up, respectively. Crossed lines denotes patients that moved away from study city but planned to remain on PrEP (not included in analysis). Percentages are derived from total number of patients that initially made appointments.

Retention in Care

We explored factors related to retention in care. The outcome variable was having attended at least one follow-up appointment every 6 months. Of the 116 patients who started PrEP, 76% attended at least one follow-up appointment; 16% (n = 18) were not yet due for a follow-up appointment, but had one scheduled; and 9% (n = 10) did not attend any follow-up visits or have a future appointment scheduled. Among those patients who had been taking PrEP for at least 6 months (n = 82), and therefore long enough to be eligible for follow-up, most patients (n = 70, 85%) had completed an appointment during every 6-month period they were on PrEP. The average percentage of 6-month periods with visits for individuals on PrEP was 92% (SD = 23%, Median = 100%, Range = 0–100%). Thirty-five patients had been prescribed PrEP long enough to be eligible for multiple follow-up visits. Of these patients, 74% (n = 26) had completed an appointment during every 6-month period they were on PrEP. Patients who initiated PrEP were eligible for an average of 1.10 follow-up visits (SD = 1.32, range = 0–8).

Patients who had been on PrEP longer were less likely to attend an appointment every 6 months than those on PrEP for a shorter duration (B = −0.12, SE = 0.04, OR = 0.88, p < 0.01). The odds of completing an every-6-monthly appointment decreased by 12% for each additional month on PrEP. Of patients taking PrEP for 1 year or less, 93% completed 6-monthly appointments, but only 76% of those who had been taking PrEP for more than 1 year did so. Although not statistically significant, patients who were Black or of other races were marginally less likely to meet guidelines as compared to White patients, B = −1.46, SE = 0.87, OR = 0.23, p = .09 and B = −1.70, SE = 0.91, OR = 0.28, p = .06, respectively. Specifically, 90% of White patients, 79% of Black patients, and 73% of patients of other races had completed every-6-monthly appointments. No other factors were associated with meeting guidelines for follow-up appointments.

HIV and STI Testing

We explored factors related to HIV and STI testing. The outcome variables were completing HIV testing and STI screening every 3 months and 6 months, respectively. Over half of patients taking PrEP (55%) had received the recommended number of quarterly HIV tests. On average, they had received 75% (SD = 33%, Median = 100%) of the recommended number of HIV tests. For patients who had taken multiple HIV tests, the average gap between HIV tests was 4.03 months (SD = 2.28, Median = 3, Range = 2–13).

Two-thirds (67%) of patients taking PrEP had received the recommended number of Chlamydia and Gonorrhea tests, and 82% had received the recommended number of Syphilis tests. Sixty-two percent of patients had received the recommended number of tests for all three STIs. On average, patients taking PrEP had received 73% (SD = 42%, Median = 100%) of the recommended number of Chlamydia tests, 72% (SD = 42%, Median = 100%) of the recommended number of Gonorrhea tests, and 85% (SD = 33%, Median = 100%) of the recommended number of Syphilis tests.

Patients who had been on PrEP longer were less likely to meet the guidelines for HIV testing than those on PrEP for a shorter duration (B = −0.07, SE = 0.03, OR = 0.94, p < .05). Thus, the odds of meeting the guidelines for HIV testing were reduced by 6% for each additional month on PrEP. Although 68% of those who had been taking PrEP for 1 year or less met the STI testing recommendations, only 32% of those who had been taking PrEP for more than 1 year did so. Although a simple logistic regression showed that those enrolled in the medication management program were more likely to meet guidelines for HIV testing than those not enrolled (B = 0.93, SE = 0.46, OR = 2.54, p < .05), after controlling for time on PrEP, this association was no longer significant (B = 0.77, SE = 0.48, OR = 2.16, p = .11). No other factors were associated with meeting guidelines for HIV testing.

Patients who had been referred to the clinic by word of mouth (from partners, friends, or others); their primary care physicians (PCPs); or unknown mechanisms were more likely to receive recommended STI testing than those with other sources of referral (primarily self-referred), B = 1.86, SE = 0.91, OR = 6.40, p < .05; B = 2.17, SE = 0.90, OR = 8.79, p < .05; and B = 1.86, SE = 0.83, OR = 6.41, p < .05, respectively. Those diagnosed with an STI at baseline were more likely to meet guidelines for testing than those without an STI at baseline (B = 2.07, SE = 0.96, OR = 7.93, p < .05). Just over half (57%) of those without STIs at baseline received recommended ongoing testing, while 86% of those with diagnoses at baseline received recommended tests. Finally, those enrolled in the medication management program (n = 32) were more likely to meet guidelines than those that were not (B = 2.26, SE = 0.78, OR = 9.55, p < .01). Only half (52%) of those not enrolled in the medication management program met guidelines for STI testing, while 86% of those enrolled in the program met guidelines.

STI Diagnoses

At baseline, 106 patients were tested for Chlamydia, 106 for Gonorrhea, and 110 for Syphilis. Of those tested, 10% of patients (n = 11) were diagnosed with Chlamydia, 8% (n = 8) with Gonorrhea, and 5% (n = 5) with Syphilis. Overall, 17% of patients tested (n = 19) had at least one STI at baseline. During follow-up visits, 64 patients were tested for Chlamydia, 64 for Gonorrhea, and 69 for Syphilis. Of those tested, 27% (n = 17) were diagnosed with Chlamydia, 11% (n = 7) with Gonorrhea, and 4% (n = 3) with Syphilis; 25% of the 80 patients tested for at least one STI during follow-up (n = 20) were diagnosed with at least one STI.

During the study period, 64 patients received multiple Gonorrhea and Chlamydia tests and 69 received multiple Syphilis tests. For patients receiving multiple tests, 8% (n = 5) were diagnosed with Gonorrhea more than once, 13% (n = 8) with Chlamydia more than once, and 3% (n = 2) with Syphilis more than once; 14% (n = 11) of the 80 patients receiving multiple tests for at least one of the three STIs were repeatedly diagnosed with at least one STI.

We explored factors associated with STI diagnosis while taking PrEP, with the outcome variable being diagnosis of Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, or Syphilis at any follow-up point. Only those who had received at least one follow-up STI test were included in this analysis. Patients who had been on PrEP longer were more likely to have an STI diagnosis than those on PrEP for a shorter duration, B = 0.09, SE = 0.04, OR = 1.10, p < .05. Among those who had been on PrEP for 1 year or less, 32% had at least one STI diagnosis, while 68% of those who had been taking PrEP for more than 1 year had an STI diagnosis. Notably, time on PrEP was strongly correlated with the total number of STI tests, r = .66, p < .001. Those on PrEP for 1 year or less had received an average of 3 follow-up tests (SD = 1.59, Median = 3, Range = 1–8), while those on PrEP for more than 1 year had received an average of 8 tests (SD = 5.64, Median = 7, Range = 1–21). No other factors were associated with diagnosis.

Preventative Health Care

When first visiting the clinic, many patients had not received recommended preventative care. Nearly half (49%, n = 65) had not been vaccinated for HAV, while 29% (n = 39) had not been vaccinated for HBV. The great majority of participants age 26 or younger (88%) had not been vaccinated for HPV. Only 36% of patients (n = 48) had received all recommended preventative care. Age was the only factor associated with having received recommended care at baseline. Participants who had received all recommended care at baseline were older (B = 0.05, SE = 0.02, OR = 1.05, p < .01). Less than a quarter (23%) of those under age 35 had received all recommended care, while 47% of those 35 years or older had received all recommended care.

After attending the clinic, many patients received preventative care; 57% of those not vaccinated for HAV received the vaccination, as did 44% of those not vaccinated for HBV and 62% of those not vaccinated for HPV who were age 26 or younger. Overall, 69% of patients (n = 93) had received all recommended preventative care after clinic follow-up.

Discussion

This study highlights adherence to return visits and testing recommendations among PrEP users in a clinic-based PrEP cohort. There have been relatively few studies evaluating this clinical setting and even fewer that focused on preventative healthcare in the PrEP clinic setting. Patients at our clinic demonstrated high rates of follow-up and HIV testing and a large increase in completion of recommended immunizations after initiating PrEP.

We expected a lower retention rate compared to rigorously monitored research cohorts. However, of the 135 patients that initially presented to the PrEP clinic, 86% started PrEP, and among those patients taking PrEP long enough to be due for a follow-up visit, we observed >90% retention in care. Some possible explanations of the high retention include that compared to some studies, our cohort was older and less racially diverse. In addition, most of our patients were insured. This may mean that PrEP users in our cohort were more likely to have had previous contact with the healthcare system and had fewer barriers to overcome than expected, leading to higher retention. However, retention dropped to 76% at one year for eligible patients. Further follow-up is needed to determine if continued attrition will occur.

Another noteworthy finding in our study was that those enrolled in our medication management program were more likely to complete recommended STI testing than those not enrolled. Of interest is that this program is not run through our clinic, but is available to patients utilizing the pharmacy within our institution for many chronic health conditions. Although the program is designed mainly to encourage medication adherence and to address insurance coverage issues, the pharmacists conducting phone calls also are aware of the follow-up testing required while on various medications, including PrEP. Testing reminders received by patients in the program may have encouraged regular STI testing. With a coordinated approach, similar programs in clinic settings could lead to improvements in both medication adherence and follow-up testing with a relatively low investment of resources – one phone call to each patient twice per year, on the 3-month interval at which they need HIV and/or STI testing but are not coming for an appointment with a medical provider.

Although PrEP discontinuation is a concern commonly voiced by some medical providers, our study provides additional evidence that PrEP discontinuation rates are low. Of the 14 patients that discontinued PrEP, only 3 did so due to side effects, with 3 additional patients discontinuing PrEP due to a change in their HIV acquisition risk. Only 7% of our patients discontinued PrEP without returning to the clinic or providing a reason for discontinuation. Discontinuation in our sample was relatively rare, making it difficult to determine potential predictors. Future studies should explore similar samples over an even longer time frame.

Another commonly-reported concern is patients’ adherence to recommended follow up visits and HIV and STI testing schedules. Although we saw high overall rates of visit completion, we found that patients who had been on PrEP longer were less likely to meet guidelines for follow-up visits than those on PrEP for a shorter duration. The reason for this is unclear, and it would be beneficial to see how patients fare over a longer follow-up period. For established PrEP patients, it may be possible to decrease the frequency of visits, although data is lacking in this area. Bruno and Saberi (2012) postulated that clinical pharmacists in a protocol-driven program could decrease the number of healthcare visits while meeting recommended PrEP guidelines. This is already being implemented in some PrEP clinics with early success (Bruno and Saberi, 2012; Marcus et al., 2016).

As described earlier, one concern about PrEP is that behavioral compensation due to perceptions of low risk may lead to increased risky behaviors. However, one perceived benefit of PrEP is the increased rate of STI testing (Scott and Klauser, 2016), which may offset risk compensation (Jenness et al., 2017). In our cohort, a number of patients refused Gonorrhea and Chlamydia swab testing for various reasons, including low perceived risk since their prior clinic visit and the costs associated with testing. Future research should examine associations between PrEP users’ sexual behaviors, risk perceptions, and adherence to testing guidelines. Reducing the costs associated with STI testing may also increase willingness to meet guidelines.

A concerning finding in our cohort was that STI testing and HIV testing completion rates decreased with the duration of time on PrEP. We also noted an increase rate of STI diagnoses in follow-up than at baseline (25% vs 17%), primarily from an increase in Chlamydia infection rate. These findings raise the question of whether habituation to taking PrEP over time reduces individuals’ perception of the importance of such testing (and completion of clinic visits). Research on such perceptions in long-term PrEP users is needed, especially in light of the current increasing rates of STIs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). A recent study noted a 72% increase in STI diagnoses following PrEP initiation compared to STI rates in the year prior to PrEP (Nguyen et a., 2018). This outcome highlights the need for continued active surveillance of STIs in PrEP patients.

Regarding STI diagnoses, the PROUD study noted 50–57% of PrEP patients diagnosed with at least one STI over 48 weeks while Liu et al. noted a 51% rate of STI diagnosis over 16 months of follow-up (McCormack et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016). Comparatively, only 25% of those tested for STIs in our cohort were positive for an STI in follow-up. This may be due to omissions from patients not completing testing, although this was a minority of our patients. Additionally, our cohort may represent a lower risk population compared to other PrEP clinics. Teaching on sexual risk and health at PrEP visits may be beneficial but further collection of sexual behavior data is needed to determine the cause of our lower rates of STI.

Our study also confirmed that PrEP visits could be an opportunity to deliver other preventative healthcare. Almost half of patients were not immune to Hepatitis A, and nearly 60% completed the vaccination series after initiating PrEP. Of patients eligible for HPV immunization, 88% were not immunized, but 62% of them completed their HPV immunization series after starting PrEP. Overall, nearly two-thirds of patients who were not immune to Hepatitis A, Hepatitis B, or HPV prior to starting PrEP went on to complete all recommended immunizations. Younger individuals were less likely than older individuals to meet preventative healthcare guidelines when first presenting at the clinic and may particularly benefit from this additional contact with the medical system.

Although not a primary focus of our study, it is important to note that out of 116 patients who started PrEP, there were no new instances of HIV. There were two instances of patients who were diagnosed with HIV on their initial visit. We also had instances of patients that were transitioned from post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to PrEP. These patients with recent possible HIV exposures are ideal candidates for PrEP (Jain, Krakower, & Mayer, 2015).

A major limitation of our study is lack of PrEP adherence data that would further delineate our cohort and their adherence to CDC recommendations. Another limitation of our study is the relatively low percentage of African-American and Latino patients. PrEP uptake in the groups at highest risk for HIV acquisition has been an ongoing concern, and potential disparities in uptake were also seen in our study. In Milwaukee County, the vast majority of new HIV infections occur in the young African American MSM community. Although our clinic did have 88% MSM patients, only 15% were African American and 7% were Latino (29% non-White). Therefore, generalizability of our cohort may be limited compared to other PrEP clinic populations. Still, we found no differences in PrEP continuation rates or adherence to clinic visits or testing requirements among African-American or Latino PrEP users. Another limitation of the study is that by the nature of retrospective chart reviews, we are dependent on the data being supplied by the patient and the provider, which may be limited. However, chart review allowed us to include every patient who was seen in clinic, an advantage over survey studies that rely on active participation, which may be biased toward including motivated patients. Our clinic is likely similar to other Midwest academic Infectious Diseases clinics with easy access to pharmacists and laboratories, but this setting may not generalize to other non-academic PrEP clinics or populations elsewhere in the United States.

Given the high rates of PrEP retention, adherence to testing requirements, and administration of preventative health measures, this study reaffirms that PrEP can be successfully administered in clinics outside the rigors of clinical trial settings. Our clinic had no specific resources dedicated to ensuring the success of PrEP patients, and thus, this data should provide encouragement to other clinicians or organizations concerned that a lack of resources will result in suboptimal PrEP outcomes. To the contrary, expanding PrEP availability can be undertaken successfully within usual clinical practice. Although additional study of PrEP in typical clinical settings is needed, especially in clinics with larger numbers of African-American MSM patients, clinicians should continue to expand their provision of PrEP to maximize its potential to reduce HIV transmission.

Contributor Information

Matthew A. Hevey, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri

Jennifer L. Walsh, Center for AIDS Intervention Research, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Andrew E. Petroll, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Medical College of Wisconsin

References

- Baeten JM, et al. (2012). Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV-1 Prevention among Heterosexual Men and Women. New England Journal of Medicine; 367(5): 399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno C, Saberi P (2012). Pharmacists as providers of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy; 34(6): 803–806. DOI: 10.1007/s11096-012-9709-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). HIV Surveillance Report, 2015; vol. 27 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2016. Accessed 10/22/2017. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Interim Guidance: Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in Men Who Have Sex With Men. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60(3): 65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2016 Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Chan PA, et al. (2016). Implementation of Preexposure Prophylaxis for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Prevention Among Men Who Have Sex With Men at a New England Sexually Transmitted Diseases Clinic. Sexually Transmitted Diseases; 43(11): 717–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PA, et al. (2016). Retention in care outcomes for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation programmes among men who have sex with men in three US cities. Journal of the International Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Society; 19(1): 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT (2010). Preexposure prophylaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes; 54(5): 548–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, et al. (2010). Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New England Journal of Medicine; 363: 2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, et al. (2014). Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infectious Diseases; 14(9): 820–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Krakower DS, Mayer KH (2015). The Transition From Postexposure Prophylaxis to Preexposure Prophylaxis: An Emerging Opportunity for Biobehavioral HIV Prevention. Clinical Infectious Diseases 60(Supple3): S200–S204. DOI: 10.1093/cid/civ094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness SM, et al. (2017). Incidence of Gonorrhea and Chlamydia Following Human Immunodeficiency Virus Preexposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Modeling Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases; 65(5): 712–718. DOI: 10.1093/cid/cix439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AY, et al. (2016). Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine; 176(1): 75–84. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JL, et al. (2013). No Evidence of Sexual Risk Compensation in the iPrEx Trial of Daily Oral HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis. PLOS ONE; 8(12): e8197 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JL, et al. (2016). Preexposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in a Large Integrated Health Care System: Adherence, Renal Safety, and Discontinuation. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes; 73(5): 540–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack S, et al. (2016). Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet; 387: 53–60. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery MC, et al. (2016). Adherence to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in a Clinical Setting. PLOS ONE; 11(6): e0157742 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng BE, et al. (2014). Relationship between disclosure of same-sex sexual activity to providers, HIV diagnosis and sexual health services for men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health; (105)3: e186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen V, et al. (2018). Incidence of sexually transmitted infections before and after preexposure prophylaxis for HIV. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Behavior; 32: 523–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg CE, et al. (2017). Behavioral Changes Following Uptake of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in a Clinical Setting. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome and Behavior DOI: 10.1007/s10461-017-1701-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroll AE, Mosack KE (2011). Physician awareness of sexual orientation and preventive health recommendations to men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases; 38(1): 63–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott HM, Klausner JD (2016). Sexually transmitted infections and pre-exposure prophylaxis: challenges and opportunities among men who have sex with men in the US. AIDS research and therapy; 13(1): 1–5. DOI: 10.1186/s12981-016-0089-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, et al. (2015). Vital Signs: Estimated Percentages and Numbers of Adults with Indications for Preexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Acquisition. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report; 64(46): 1291–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside YO, Harris T, Scanlon C, Clarkson S, Duffus W (2011). Self-perceived risk of HIV infection and attitudes about preexposure prophylaxis among sexually transmitted disease clinic attendees in South Carolina. AIDS patient care and STDs; 25(6): 365–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Public Health Service. (2014). Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States – 2014: A Clinical Practice Guideline Published May 14, 2014; pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]