Abstract

Objective:

Severe sepsis is a significant cause of healthcare use and morbidity among pediatric patients, but little is known about readmission diagnoses. We sought to determine the most common readmission diagnoses after pediatric severe sepsis, the extent to which post-sepsis readmissions may be potentially preventable, and whether patterns of readmission diagnoses differ compared to readmissions after other common acute medical hospitalizations.

Design:

Observational Cohort Study

Setting:

National Readmission Database (2013-2014), including all-payer hospitalizations from 22 states.

Patients:

4528 pediatric severe hospitalizations, matched by age, gender, comorbidities, and length of stay to 4528 pediatric hospitalizations for other common acute medical conditions.

Interventions:

None

Measurements and Main Results:

We compared rates of 30-day all-cause, diagnosis-specific, and potentially preventable hospital readmissions using McNemar’s chi-square tests for paired data. Among 5841 eligible pediatric severe sepsis hospitalizations with live discharge, 4528 (77.5%) were matched 1:1 to 4528 pediatric hospitalizations for other acute medical conditions. Of 4528 matched sepsis hospitalizations, 851 (18.8% (95% CI 16.0, 18.2)) were re-hospitalized within 30 days, compared to 775 (17.1% (95% CI 17.1, 20.0)) of matched hospitalizations for other causes (p=0.02). The most common readmission diagnoses were chemotherapy, device complication, and sepsis, all of which were several-fold higher after sepsis versus after matched non-sepsis hospitalization. Only 11.5% of readmissions were for ambulatory care sensitive conditions compared to 23% of rehospitalizations after common acute medical conditions.

Conclusion:

More than 1 in 6 children surviving severe sepsis were re-hospitalized within 30 days, most commonly for maintenance chemotherapy, medical device complications, or recurrent sepsis. Only a small proportion of readmissions were for ambulatory care sensitive conditions.

Keywords: Sepsis, Patient Readmission, Critical Care Outcomes, Pediatrics, Shock, Septic, Intensive Care Units, Pediatric

Introduction

Severe sepsis is a significant cause of morbidity and health care utilization among pediatric patients, with 2005 U.S. cost estimates of up to $4.8 billion dollars per year(1). The prevalence of pediatric severe sepsis continues to rise, resulting in growing population of pediatric sepsis survivors(2). However, while in-hospital survival has improved, pediatric sepsis survivors experience a high rate of hospital readmission and increased risk of death compared to the general pediatric population(3).

In adult sepsis survivors, as many as 40% of hospital readmissions are potentially preventable, suggesting an opportunity for improvement with better post-hospital care(4). Moreover, a small number of conditions (recurrent infection, congestive heart failure , acute renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, aspiration) account for a bulk of the readmissions(5–12). Anticipating and mitigating risk for these common and potentially preventable readmission diagnoses has been recommended as a strategy to enhance recovery in adult sepsis survivors(13).

In contrast to adults, however, little is known about patterns of hospital readmission following pediatric severe sepsis. Thus, in a large and representative cohort of pediatric severe sepsis hospitalizations, we sought to determine the common readmission diagnoses after pediatric severe sepsis, the extent to which post-sepsis readmissions are potentially preventable, and whether patterns of readmission diagnoses differ compared to readmissions after other common causes of acute medical hospitalizations.

Methods

We studied pediatric hospitalizations (age ≤18 years) from the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD), 2013-2014 (14). The NRD was developed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) to provide nationally representative information on hospital readmissions. NRD includes all-payer hospitalization claims from 22 State Inpatient Databases, representing 51% of the U.S. population. Data on patients aged <1 year were available for 9 of 21 states in 2013 and 12 of the 22 states in 2014.

We excluded hospitalizations from the neonatal/perinatal period and pregnancy-related hospitalizations (Appendix 1, Online Supplement) since neonatal and maternal sepsis are often considered as separate entities from pediatric sepsis(1, 15, 16). We also excluded hospitalizations without live discharge. Finally, we excluded hospitalizations with a December discharge month (to allow for a full 30-day follow-up in the dataset), and hospitalizations in which the patient was the resident of another state (in which case a readmission would be more likely to occur in a state not included in the NRD).

Identification of Severe Sepsis Hospitalizations:

We identified hospitalizations with severe sepsis using standard claims-based approaches: either (1) explicit International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for severe sepsis (995.92) or septic shock (785.52), or (2) by Dombrovskiy criteria, which requires concurrent codes for both sepsis/bacteremia and acute organ dysfunction(Appendix 1, Online Supplement) (17). For patients with multiple severe sepsis hospitalizations, all eligible hospitalizations were included.

Identification of Nonsepsis Hospitalizations.

To examine how patterns of readmission differ after severe sepsis versus after other common acute medical hospitalizations, we matched severe sepsis hospitalizations to hospitalizations for common acute pediatric medical conditions. Common acute medical diagnoses were determined from the top diagnostic categories from HCUP and a recent study of diagnoses resulting in pediatric hospitalizations(18). Comparison hospitalizations were identified by a principal diagnosis category of asthma, viral infection, pneumonia, acute bronchitis, upper and lower respiratory tract infection, influenza, urinary tract infection, nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, intestinal infection, non-infectious gastroenteritis, colitis, epilepsy/seizures, diabetes mellitus, fluid and electrolyte abnormalities, appendicitis, aspiration pneumonitis and fever of unknown origin.

Matching severe sepsis and nonsepsis hospitalizations.

Patients were matched exactly by age group (<1 year, 1-4 years, 5-9 years, 10-14 years, and 15-18 years), sex, length of hospitalization (<3 days, 4-7 days, 7-14 days, 15-28 days and >28 days), and type and number of Complex Chronic Conditions present in the hospitalization diagnosis codes(19, 20) (Appendix 1, Online Supplement). For primary analysis, patients were matched 1:1 by above metrics. We also performed a sensitivity analysis in which patients were matched 1:n. Specifically, each sepsis hospitalization was matched to up to 5 controls.

Identification of Potentially Preventable Re-hospitalizations:

To determine which hospital readmissions were potentially preventable, we examined ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC), as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (21). ACSC are diagnoses for which effective outpatient treatment may prevent hospitalization(22–24). In children, the following diagnoses are considered as ACSC: asthma, bacterial pneumonia, gastroenteritis, dehydration, uncontrolled diabetes/diabetic short-term complications, and perforated appendicitis(24). We classified readmissions as being for a pediatric ACSC based on the principal diagnosis category, as defined by the HCUP clinical classification system (25).

Outcomes:

We measured rates of hospital readmission—overall, ACSC, and by diagnosis category—at 30 days post-discharge. We selected 30-days post discharge as the primary endpoint to maximize the sample of eligible index hospitalizations (since patients cannot be followed year-to-year within the NRD). However, we also examined 90-day readmissions among patients discharged in January-September, for whom full 90-day follow-up was available. We compared rates of re-hospitalization between the matched cohorts, to understand how patterns of readmissions after severe sepsis differ from readmissions after other common pediatric acute medical conditions.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses:

We compared the rates and diagnoses of 30-day readmissions by age category. As children with complex medical conditions differ from those without, we measured rates and diagnoses of 30-day readmission in patients with versus without pre-existing complex chronic conditions. Given the number of children with malignancy, we examined the rates of 30-day readmissions between matched cohorts and by malignancy status, as well as rates of elective readmissions (in order to exclude scheduled hospitalizations for chemotherapy).

Statistical Analysis:

Patient characteristics are presented as mean (Standard Deviation), numbers (percentage with 95% CI-confidence interval), or medians (IQR-Interquartile Range). All analyses were conducted with StataMP software version 15 (StataCorp). We compared readmission rates using McNemar’s X2 tests for paired data, with significance of p<0.05.

Results:

We identified 7727 pediatric severe sepsis hospitalizations, of which 6924 (89.6%) had a live discharge, and 5841 (75.6%) met study inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of these 5841 potentially eligible severe sepsis hospitalizations, 4528 (77.5%) were matched 1:1 to a non-sepsis hospitalization and included in the primary analysis. There were 4325 unique patients with severe sepsis; only 183 (4.2%) patients had >1 index severe sepsis hospitalization. The severe sepsis cohort was indistinguishable from the matched cohort in terms of age, sex, length of stay category, and number and type of comorbidities (p>0.05 for each) (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Identification and Matching of the Severe Sepsis and Acute Medical Condition Cohorts

Legend: Severe sepsis was identified in 0.75% of non-neonatal, non-pregnancy related pediatric hospitalizations of the Nationwide Readmissions Database in 2013-2014.

Table 1.

Patient and Hospitalization Characteristics of Matched Severe Sepsis and Acute Medical Condition Cohorts

| Patient and Hospitalization Characteristics | Severe Sepsis n(%) | Acute Medical Conditions n(%) | P-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 4528 | 4528 | |

| Age, years Median, (IQR) | 11(3-16) | 11(3-16) | 0.91 |

| Age Category, years | |||

| 0 | 542 (11.9%) | 542 (11.9%) | 1.00 |

| 1-4 | 798 (17.6%) | 798 (17.6%) | 1.00 |

| 5-9 | 641 (14.2%) | 641 (14.2%) | 1.00 |

| 10-14 | 887 (19.6%) | 887 (19.6%) | 1.00 |

| >14 | 1660 (36.7%) | 1660 (36.7%) | 1.00 |

| Female | 2268 (50.1%) | 2268 (50.1%) | 1.00 |

| Length of Stay Category | |||

| Less than 3 days | 867 (19.2%) | 867 (19.2%) | 1.00 |

| 3-7 days | 1321 (29.2%) | 1321 (29.2%) | 1.00 |

| 7-14 days | 1109 (24.5%) | 1109 (24.5%) | 1.00 |

| 14-28 days | 809 (17.9%) | 809 (17.9%) | 1.00 |

| >28 days | 422 (9.3%) | 422 (9.3%) | 1.00 |

| Number of Chronic Conditions | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (0-2) | 1 (0-2) | 0.85 |

| 0 | 1625 (35.9%) | 1625 (35.9%) | 1.00 |

| 1 | 1289 (28.4%) | 1270 (28.0%) | 0.99 |

| 2 | 889 (19.6%) | 910 (20.1%) | 0.99 |

| 3 | 480 (10.6%) | 477 (10.6%) | 0.99 |

| 4 | 189 (4.2%) | 195 (4.3%) | 0.99 |

| 5+ | 56(1.2%) | 52 (1.2%) | 0.99 |

| Type of Chronic Conditionsb | |||

| Cardiovascular | 643 (14.2%) | 643 (14.2%) | 1.00 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1072 (23.7%) | 1072 (23.7%) | 1.00 |

| Genetic/Metabolic | 995 (21.9%) | 995 (21.9%) | 1.00 |

| Hematologic/Immunologic | 554 (12.2%) | 554 (12.2 %) | 1.00 |

| Malignancy | 490 (10.8%) | 490 (10.8%) | 1.00 |

| Neonatal | 104 (2.3%) | 127 (2.8%) | 0.13 |

| Neuromuscular | 930 (20.5%) | 930 (20.5%) | 1.00 |

| Renal | 326 (7.2%) | 326 (7.2%) | 1.00 |

| Respiratory | 361 (8.0%) | 361 (8.0%) | 1.00 |

| Transplant | 194 (4.3%) | 197 (4.4%) | 0.88 |

| Technologic Dependence | 1153 (25.5%) | 1153 (25.5%) | 1.00 |

Statistical significance determined using chi-square, Wilcoxon rank-sum or t-test as appropriate

Percent does not total to 100% as patients may have more than one co-morbidity

IQR, Interquartile Range

The severe sepsis cohort was 50.1% percent female with a median age of 11 years. 542 (12%) were less than 1 year. 2903 (64%) had at least one comorbidity, most commonly technological dependence (25.5%), gastrointestinal (23.7%), genetic/metabolic (21.9%), and neuromuscular (20.5%) (Table 1). Patients had a median of 1 co-morbidity (IQR 0-2).

Of the 4528 severe sepsis survivors, 851 (18.8% (95% CI 17.7, 20.0) were re-hospitalized within 30 days of index discharge. In total, the cohort experienced 1051 readmissions within 30 days, of which 121 (11.5%) were for an ACSC. Sixteen (1.5%) were readmitted and died within 30 days. Of the 3652 survivors with a Jan-Sept discharge, 1092 (29.9%) were readmitted within 90 days.

The most common 30-day readmission diagnoses were maintenance chemotherapy (occurring in 3.0% (95% CI 2.5, 3.5) of severe sepsis survivors); complications of a medical device (2.6% (95% CI 2.1, 3.1) of severe sepsis survivors); sepsis (1.9% (95% CI 1.5,2.3)); leukocytosis/leukopenia (0.9% (95% CI 0.6,1.3)); pneumonia (0.9% (95% CI 0.7,1.3) and complications of medical or surgical care (0.8% (95% CI 0.6,1.1)) (Table 2). The top 10 readmission diagnoses accounted for 66.6% of all 30-day readmissions. Patients were readmitted for maintenance chemotherapy a median 11 days after hospital discharge for severe sepsis. The median length of stay for maintenance chemotherapy hospitalizations was 4 days (IQR 3-5 days). When examining readmission to 90 days, the top 5 diagnoses were unchanged, but device complications supplanted maintenance chemotherapy as the most common readmission diagnosis (Supplemental Table E1a).

Table 2.

Most Frequent Readmission Diagnoses after Severe Sepsis and Matched Hospitalizations for Common Pediatric Acute Medical Conditions

| Severe Sepsis (n=4528) | Acute Medical Conditions (n=4528) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosisa | No. of Survivors with a Readmission for this Diagnosis | % (95%CI) | No. of Survivors with a Readmission for this Diagnosis | % (95%CI) | P-Valueb |

| Maintenance Chemotherapy | 136 | 3.0 (2.5-3.5) | 81 | 1.8 (1.4-2.2) | <.001 |

| Complications of device, implant or graft | 116 | 2.6 (2.1-3.1) | 46 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | <.001 |

| Sepsis | 85 | 1.9 (1.5-2.3) | 30 | 0.7 (0.4-0.9) | <.001 |

| Leukopenia or Leukocytosis | 42 | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 21 | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | .005 |

| Pneumonia | 42 | 0.9 (0.7-1.3) | 47 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | .82 |

| Complications of Medical Care | 37 | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 35 | 0.8 (0.5-1.1) | .72 |

| Fluid/Electrolyte Disorders | 28 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 34 | 0.8 (0.5-1.0) | .61 |

| Upper Respiratory Tract Infection | 27 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | 26 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | .89 |

| Seizure Disorder | 26 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 47 | 1.0 (0.7-1.3) | .01 |

| Acute Respiratory Failure | 25 | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | 29 | 0.6 (0.4-0.9) | .59 |

Listed in order of frequency among severe sepsis survivors. The top 10 readmission diagnoses account for 66% of all readmissions within 30 days after hospitalization for severe sepsis.

Calculated using McNemar’s X2 tests.

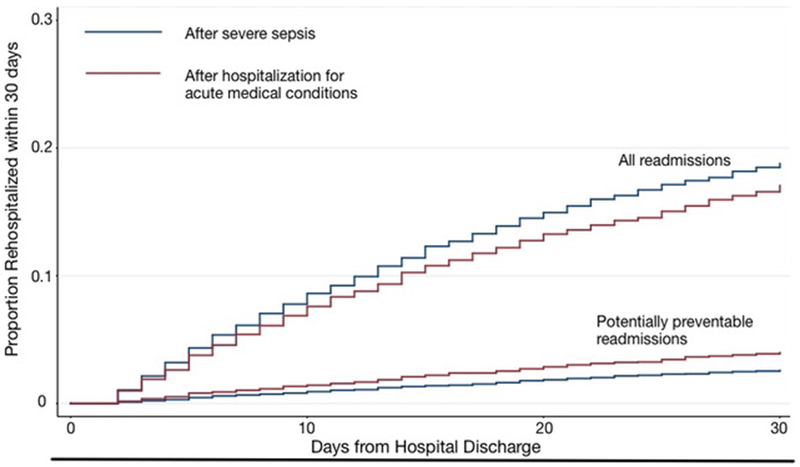

The rate of all-cause 30-day readmission after matched acute medical hospitalizations was 17.1%, versus 18.8% after severe sepsis, p=0.02 (Figure 2). The top 10 diagnoses accounted for 51.7% of readmissions after matched acute medical hospitalizations (Table 2). Twelve (1.3%) were readmitted and died within 30 days. Of the 3652 survivors with a Jan-Sept discharge, 1092 (29.9%) were readmitted within 90 days.

Figure 2:

Total and Potentially Preventable 30-day Readmissions Among Survivors of Severe Sepsis and Matched Hospitalizations for Acute Medical Conditions

Legend: Potentially preventable readmissions include asthma, bacterial pneumonia, gastroenteritis, dehydration, uncontrolled diabetes/diabetic short-term complications, and perforated appendicitis.

As with the severe sepsis cohort, the two most common 30-day readmission diagnoses were maintenance chemotherapy (occurring after 1.9% of acute medical condition hospitalizations (95% CI 1.4, 2.2)) and complications of a medical device or medical/surgical care (1.8% (95% CI 1.4, 2.2) of acute medical condition hospitalizations). Other top causes for readmission included seizure disorders, pneumonia, diabetic complications, complications of medical care, fluid/electrolyte abnormalities, sepsis, respiratory failure or upper respiratory tract infections. However, while maintenance chemotherapy was the most common readmission diagnosis in both cohorts, the rate of re-hospitalization for maintenance chemotherapy was 1.7-fold higher after severe sepsis versus matched hospitalizations for other causes (3.0% vs 1.8%, p <0.001) (Table 2). Readmissions for medical device-related complications (e.g. bloodstream infection or mechanical complication) and readmissions for sepsis were more than 2.5 times as common after severe sepsis versus after matched hospitalizations for other causes, p<0.001 for each.

Readmissions for ACSC were less common after severe sepsis versus after non-sepsis hospitalizations, occurring after 2.6% (95% CI 2.2, 3.1) vs. 4.0% (95% CI 3.5, 4.6) of hospitalizations respectively, p<0.001. However, when sepsis is included as a preventable readmission diagnosis, rates of potentially preventable readmissions were indistinguishable, 4.6% (95% CI 4.0, 5.3) vs. 4.4% (95% CI 3.8,5.0), p=0.76. Infection-related readmission occurred after 5.2% (95%CI 4.6,5.9) of sepsis hospitalizations versus after 4.5% (95%CI 3.9,5.2) matched non-sepsis hospitalizations, p=0.05.

In the sensitivity analysis with 1:n matching, rates of 30-day readmission after severe sepsis and matched acute medical condition cohorts were different, p=0.02 (as in the primary analysis). Likewise, as in the primary analysis, sepsis survivors experienced higher rates of re-hospitalization for maintenance chemotherapy, device complications and sepsis (eTable 7, Online Supplement).

Patterns of readmission were similar when examined by age-subgroups, with maintenance chemotherapy, device complications, and sepsis being the top three readmission diagnoses after severe sepsis among children ages 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, and 15+ years. Among infants, however, the most common readmissions diagnoses were device complications and respiratory diagnoses (bronchiolitis, acute respiratory failure and upper respiratory infection) (eTable 2, Online Supplement).

1625 (35.9%) severe sepsis survivors had no pre-existing chronic medical conditions. The rate of re-hospitalization for these patients was just 5.9% (95% CI 4.7-7.1) versus 26.0% (95% CI 24.5-27.7) among patients with at least 1 co-morbidity, p<0.001 (eTable 3a, Online Supplement). The most common readmission diagnoses among patients without co-morbidities were complications of medical devices, sepsis, complications of medical care, and bronchiolitis (eTable 4a, Online Supplement). Vascular device or line related complications, including infections, were the most common device complication (73%). Readmissions for ACSCs were less common among patients without chronic conditions (1.2% (95% CI 0.7,1.8) vs. 3.4% among patients with at least one chronic condition (95% CI 2.8, 4.1)), p<0.001)(eTable 3a, Online Supplement).

The rate of elective 30-day readmission was 4.7% among severe sepsis survivors versus 3.6% in the matched cohort (eTable 5a, Online Supplement) (p=0.004). Among patients with malignancy, severe sepsis survivors experienced higher rates of 30-day elective rehospitalizations than matched non-sepsis survivors (eTable 5a, Online Supplement). Of the 490 patients with severe sepsis and 490 matched controls with malignancy, 252 (51.4% (95% CI 47-56)) were re-hospitalized within 30 days of sepsis compared to 198 (40.4% (95% CI 36-45)) after matched non-sepsis hospitalization (p<0.001).

Discussion

In this recent, all-payer cohort including nearly five thousand pediatric severe sepsis hospitalizations, more than one in 6 survivors experienced a 30-day readmission. However, in contrast to adult patients, the rate of potentially preventable readmissions was low (occurring in just 2.5% of sepsis survivors, and accounting for only 11.5% of all readmissions). Moreover, in contrast to adult patients, for whom recurrent sepsis is the most common readmission diagnosis, children were most commonly re-hospitalized for maintenance chemotherapy, suggesting that pre-existing medical conditions are a major driver of subsequent hospitalization among pediatric sepsis patients. Indeed, the rate hospital readmission was more than 4-fold higher among patients with chronic condition(s) compared to patients without co-morbidity.

While there was only a small difference in overall rates of all cause 30-day readmission, rehospitalization diagnoses differed in children with severe sepsis compared to similar patients hospitalized for other causes. Specifically, rates of readmission for maintenance chemotherapy, complications of medical devices, and sepsis were each about 2.5-fold higher in the sepsis cohort. In addition, the rate of readmission was higher than the 6.5% observed in the general pediatric population (26), but only slightly (1%) higher than the rate of readmission after hospitalization for acute medical conditions matched by age, comorbidities, and length of hospitalization.

Our findings are consistent with prior research in several regards. The percentage of pediatric hospitalizations with severe sepsis (0.8%) was similar to that observed in prior studies using analogous identification strategies (27). As expected, this rate is lower than the rates observed in pediatric intensive care unit populations or studies using the Angus method of severe sepsis identification (1, 15, 28). The in-hospital mortality rate of severe sepsis hospitalization (10.4%) was similar to prior studies (2, 3, 29). As expected, the rate of readmission in our study was lower than the 47% reported by Czaja, et al since we examined readmissions at 30 and 90 days after hospital discharge, rather than several years post-sepsis (3). The rates of readmission at 30 and 90 days were comparable rates of readmission after adult sepsis hospitalizations (17.9%-26% at 30-days, and 29.7%-42.6% at 90-days) (12). Finally, nearly two-thirds of the severe sepsis cohort had at least one chronic medical condition (1, 2, 30).

Our study expands on prior work in several ways. First, we found that pediatric severe sepsis survivors were readmitted for sepsis 2.5 times more commonly than similar children surviving hospitalization for other causes. This increased rate of subsequent sepsis was conserved across all age groups, and was seen in children both with and without pre-existing co-morbidities. This suggests that children who survive sepsis may be at increased risk for subsequent sepsis, as seen in adult cohorts (4, 31) and experimental animal studies (32–34). Potential mechanisms for this finding include ongoing immune(35–37) and/or microbiome dysregulation (8, 38), or underlying genetic or other differences between sepsis and non-sepsis survivors that were not accounted for in our matching approach.

Our study also highlights the stark difference between patients with and without pre-existing chronic conditions. Patients with comorbidities were more 4 times more likely to be readmitted within 30 days than children without comorbidities. In contrast to prior studies that found respiratory diagnoses were the most common causes of readmission, we found that maintenance chemotherapy was the most common reason for hospitalization in the 30 days following sepsis hospitalization among children with chronic conditions (3). Children without comorbidities were often hospitalized within 30 days of discharge for medical device complication, which were most commonly for line or vascular device associated complications. This occurs because some children, without prior chronic complex conditions, are discharged home with new central access (e.g. for completion of prolonged antibiotic therapy or parenteral nutrition) and thus are at risk of readmission for line-associated infection or other line-related complications. Similarly, children with malignancy initially hospitalized for other common medical conditions were readmitted most commonly for maintenance chemotherapy, though at a significantly lower rate. Thus, while these patients have a high rate of readmission—many subsequent hospitalizations were driven by pre-existing chronic conditions(26, 39).

Although an estimated 30% of readmissions after general pediatric hospitalization may be potentially preventable, only 2.5% of our sepsis cohort were admitted due to ACSCs, and only 11.5% of 30-day readmissions were for an established ACSC(40, 41). The rate of potentially preventable readmissions was higher in children hospitalized for common acute medical conditions (2.6% vs 4%). We hypothesize this difference may be in part due to the fact that some ACSC diagnoses (i.e. asthma) are included as index hospitalizations in the acute medical condition cohort. While complications of medical care or devices are not defined ACSCs by AHRQ, these are conditions that could potentially be averted. 3.4% of the severe sepsis cohort was readmitted for complications of medical care or devices. Thus, while readmissions for ACSCs were relatively rare, there may still be an opportunity to reduce subsequent hospitalizations in these high-risk patients (42).

This study should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, while the NRD represents nearly half of U.S. inpatient hospitalizations, infant data was limited to 9 of 21 states in 2013 and 12 of 22 states in 2014, respectively. Second, patients cannot be followed across years in the NRD. For this reason, December discharges were excluded from assessment of 30-day readmissions and October-December discharges were excluded from assessment of 90-day readmissions (to ensure that patients had a full 30 and 90 days of follow-up, respectively). This may potentially underestimate the rate of readmissions for sepsis, given the known seasonal variation and higher rates of respiratory infections in winter months (43). Third, because NRD is created from state inpatient databases, only re-hospitalizations within the same state are captured. For this reason, we excluded the small proportion of index hospitalizations among non-residents. Fourth, we used a claims-based algorithm to identify severe sepsis and septic shock hospitalizations. We required either an explicit diagnosis of severe sepsis/septic shock or concurrent diagnoses of sepsis/bacteremia plus acute organ dysfunction. This approach has greater specificity than other claims-based approaches, and has a similar positive predictive value to clinical electronic health record definitions (44, 45). There is possibility for misclassification in both directions. However, imperfect classification of sepsis versus non-sepsis hospitalization would bias toward finding no difference in rate or reason for readmission. Fifth, while ACSC represent conditions amenable to outpatient treatment for the prevention of hospitalization, in some instances, they are likely not truly preventable.

Conclusion

In a large and recent all-payer cohort of US pediatric sepsis hospitalizations, more than one in six children surviving severe sepsis hospitalization was re-hospitalized within 30 days of discharge. The majority of readmissions occurred in children with chronic comorbid conditions, with maintenance chemotherapy being the most common diagnosis. Only 11.5% of readmissions were for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. However, one in 50 children surviving hospitalization for severe sepsis had a recurrent sepsis hospitalization within 30 days—more than twice the rate of sepsis readmission following matched hospitalizations for other acute medical conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Prescott was supported by K08 GM115859 from the National Institutes of Health. Dr Shankar-Hari is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Clinician Scientist Award (CS-2016-16-011). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) not of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health or Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Footnotes

Reprints will not be ordered.

References:

- 1.Hartman ME, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, et al. : Trends in the Epidemiology of Pediatric Severe Sepsis*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2013; 14:686–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Neuman MI, et al. : Pediatric Severe Sepsis in U.S. Children’s Hospitals*. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2014; 15:798–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czaja AS, Zimmerman JJ, Nathens AB: Readmission and Late Mortality After Pediatric Severe Sepsis. PEDIATRICS 2009; 123:849–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ: Readmission diagnoses after hospitalization for severe sepsis and other acute medical conditions. JAMA 2015; 313:1055–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang DW, Tseng C-H, Shapiro MF: Rehospitalizations Following Sepsis. Critical Care Medicine 2015; 43:2085–2093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortego A, Gaieski DF, Fuchs BD, et al. : Hospital-Based Acute Care Use in Survivors of Septic Shock*. Critical Care Medicine 2015; 43:729–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMerle KM, Royer SC, Mikkelsen ME, et al. : Readmissions for Recurrent Sepsis. Critical Care Medicine 2017; 45:1702–1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prescott HC, Dickson RP, Rogers MAM, et al. : Hospitalization Type and Subsequent Severe Sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192:581–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, et al. : Increased 1-Year Healthcare Use in Survivors of Severe Sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 190:62–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayr FB, Talisa VB, Balakumar V, et al. : Proportion and Cost of Unplanned 30-Day Readmissions After Sepsis Compared With Other Medical Conditions. JAMA 2017; 317:530–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu V, Lei X, Prescott HC, et al. : Hospital readmission and healthcare utilization following sepsis in community settings. J Hosp Med 2014; 9:502–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones TK, Fuchs BD, Small DS, et al. : Post–Acute Care Use and Hospital Readmission after Sepsis. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015; 12:904–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prescott HC, Angus DC: Enhancing Recovery From Sepsis. JAMA 2018; 319:62–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: HCUP National Readmission Database (NRD) [Internet]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nrdoverview.jsp

- 15.Watson RS, Carcillo JA, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. : The Epidemiology of Severe Sepsis in Children in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167:695–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan J, Roberts S: Maternal sepsis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2013; 40:69–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dombrovskiy VY, Martin AA, Sunderram J, et al. : Rapid increase in hospitalization and mortality rates for severe sepsis in the United States: A trend analysis from 1993 to 2003*. Critical Care Medicine 2007; 35:1244–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh M-S, et al. : Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med 2016; 11:743–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blackwell M, Iacus S, King G, et al. : cem: Coarsened Exact Matching in Stata. The Stata Journal 2010; 9:1–22 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, et al. : Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatrics 2014; 14:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Guide to Prevention Quality Indicators [Internet]. [cited 2018 Oct 9] Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/ahrqqi/pqiguide.pdf

- 22.Weissman JS: Rates of avoidable hospitalization by insurance status in Massachusetts and Maryland. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 1992; 268:2388–2394 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billings J, Anderson G, Newman L: Recent Findings On Preventable Hospitalizations. Health Aff (Millwood) 1996; 15:239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bettenhausen JL, Colvin JD, Berry JG, et al. : Association of Income Inequality With Pediatric Hospitalizations for Ambulatory Care–Sensitive Conditions. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171:e170322–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM [Internet]. [cited 2018 Oct 9] Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp

- 26.Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. : Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA 2013; 309:372–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Hall M, et al. : Identifying Pediatric Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: Accuracy of Diagnosis Codes. The Journal of Pediatrics 2015; 167:1295–300.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruth A, McCracken CE, Fortenberry JD, et al. : Pediatric Severe Sepsis. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2014; 15:828–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ames SG, Davis BS, Angus DC, et al. : Hospital Variation in Risk-Adjusted Pediatric Sepsis Mortality. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 2018; 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Pappachan J, et al. : Global Epidemiology of Pediatric Severe Sepsis: The Sepsis Prevalence, Outcomes, and Therapies Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191:1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen H-N, Lu C-L, Yang H-H: Risk of Recurrence After Surviving Severe Sepsis: A Matched Cohort Study. Critical Care Medicine 2016; 44:1833–1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamim CF, Hogaboam CM, Lukacs NW, et al. : Septic mice are susceptible to pulmonary aspergillosis. Am J Pathol 2003; 163:2605–2617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamim CF, Hogaboam CM, Kunkel SL: The chronic consequences of severe sepsis. J Leukoc Biol 2004; 75:408–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deng JC, Cheng G, Newstead MW, et al. : Sepsis-induced suppression of lung innate immunity is mediated by IRAK-M. J Clin Invest 2006; 116:2532–2542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, et al. : Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA 2011; 306:2594–2605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D: Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2013; 13:260–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otto GP, Sossdorf M, Claus RA, et al. : The late phase of sepsis is characterized by an increased microbiological burden and death rate. Crit Care 2011; 15:R183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prescott HC: Toward a Nuanced Understanding of the Role of Infection in Readmissions After Sepsis*. Critical Care Medicine 2016; 44:634–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. : Pediatric Readmissions After Hospitalizations for Lower Respiratory Infections. PEDIATRICS 2017; 140:e20160938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toomey SL, Peltz A, Loren S, et al. : Potentially Preventable 30-Day Hospital Readmissions at a Childrens Hospital. PEDIATRICS 2016; 138:e20154182–e20154182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, et al. : Preventability of Early Readmissions at a Children’s Hospital. PEDIATRICS 2013; 131:e171–e181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rinke ML, Bundy DG, Chen AR, et al. : Central line maintenance bundles and CLABSIs in ambulatory oncology patients. PEDIATRICS 2013; 132:e1403–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Danai PA, Sinha S, Moss M, et al. : Seasonal variation in the epidemiology of sepsis*. Critical Care Medicine 2007; 35:410–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, et al. : Incidence and Trends of Sepsis in US Hospitals Using Clinical vs Claims Data, 2009–2014. JAMA 2017; 318:1241–1249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jolley RJ, Sawka KJ, Yergens DW, et al. : Validity of administrative data in recording sepsis: a systematic review. Crit Care 2015; 19:1303–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.