Abstract

In the last decades, the increasing evidence concerning inflammation mechanisms underlying severe eosinophilic asthma has highlighted new potential therapeutic targets and has paved the way to new selective biologic drugs. Understanding the mechanism of action and the clinical outcomes of a particular drug along with the clinical and biological characteristics of the patient population for which that drug was intended may ensure appropriate selection of patients that will respond to that drug. Under this perspective, the present review will focus on the mechanisms of action and clinical evidence of benralizumab as a treatment option for severe eosinophilic asthma, in order to provide a concise overview and a reference for clinical practice. Benralizumab is a fully humanized afucosylated IgG1κ mAb that binds to an epitope on IL-5 Rα, and inhibits IL-5 signaling. Benralizumab also sustains antibody-directed cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) of eosinophils and basophils and consequently depletes IL-5Rα-expressing cells. As a result, it is responsible for a substantial depletion of blood, tissue, and bone marrow eosinophilia. This unique mechanism of action may account for a more complete and rapid action profile. Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that benralizumab provides an optimal safety profile, and is able to significantly reduce asthma exacerbations, oral steroid intake, and to improve lung function. Some clinical predictors of enhanced clinical response to benralizumab have also been identified, including: a level of blood eosinophils ≥300 μL−1, oral steroids use, the presence of nasal polyposis, FVC <65% of predicted, and a history of three or more exacerbations per year at baseline. These results can be helpful in identifying the best responder patients to benralizumab. As a step forward, the definition of the responder profile for each of the available biological treatment options will potentially support even more the pathway to precision medicine and the critical matching of the right drug with the right patient.

Keywords: benralizumab efficacy, benralizumab safety, benralizumab mechanism of action, anti IL-5 mAbs, severe asthma, eosinophilic asthma

Introduction

An estimated 5–10% of the 300 million people worldwide who suffer from asthma have a severe form. Patients with eosinophilic airway inflammation represent approximately 40–60% of this population.1–3 Eosinophilic asthma is a relevant subtype of asthma associated with increased risk of severe exacerbations and a difficult control, despite high doses of oral and inhaled corticosteroids. In the last decades, that asthma phenotype has been extensively explored, and the increasing evidence concerning the underlying inflammation mechanisms has highlighted new potential therapeutic targets and subsequently has paved the way to new selective drugs.4 In the next few years further biologic and bio-similar molecules selectively addressing eosinophils and Th2 inflammation will become available on the market, substantially enlarging the treatment options for the patients with severe eosinophilic asthma.4 On the other hand, the lack of biomarkers specifically predicting the good clinical response to each biologic, which is currently a potential limitation in the field, may hamper the selection of the right drug for the right patient.5 Understanding the mechanism of action and the clinical outcomes of a particular drug along with the clinical and biological characteristics of the patient population for which that drug was intended to treat may ensure appropriate selection of patients that will respond to that drug.

Under this perspective the present review will focus on the mechanisms of action and clinical evidence of benralizumab, in order to provide a concise overview and a reference for clinical practice useful in increasing the knowledge of the drug and better defining its position in the context of the treatment options for severe eosinophilic asthma.

Methods

A selective search on PubMed and Medline was performed, including the following keywords: benralizumab efficacy, benralizumab safety, benralizumab mechanism of action, anti-IL 5 monoclonal antibody, and anti-IL 5 receptor monoclonal antibody. Papers published up to January 2019 were considered. Original articles, randomized clinical trials, and review papers relevant to the topic were evaluated for inclusion in the review.

Immunologic background: the added value of a receptor-blocking molecule

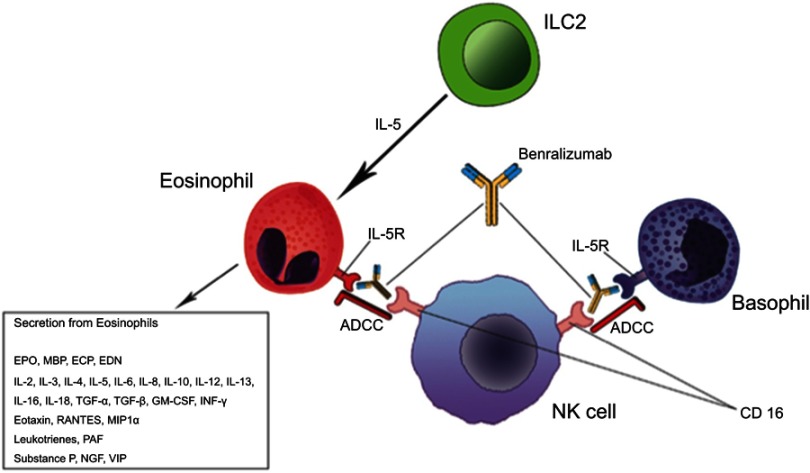

It has been known for many years that eosinophilic bronchial asthma is characterized by increased eosinophil count in the airways and peripheral blood, which has been shown to positively correlate with asthma severity.6 Under a pathophysiological and clinical perspective, eosinophils in the context of the other Th2 inflammation molecules and cells, particularly tissue-resident innate lymphoid cells type 2 (ILC2s), drive a number of mechanisms and humoral mediators (antibodies, cytokines), which account for disease progression, poor asthma control, and exacerbations7 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Benralizumab mechanism of action overview.

Endothelial cells damaging, altered repair processes, and induction of fibrosis are the most relevant ones.

Tissue eosinophils have an important role in innate immune response to exogenous agents, but they can also damage tissues by degranulation. Consequently, accumulation of eosinophils releasing their granule-associated basic proteins, lipid mediators, cytochines, and chemokines leads to potentiated airway inflammation and tissue remodeling, with increased mucus secretion and bronchial wall thickening.7

Interleukin 5 (IL-5) is a 13-amino acid protein that forms a 52-kDa homodimer binding to the IL-5 receptor on cells surface, a heterodimer composed of two subunits. The α subunit is specific for IL-5, and the β subunit is shared with the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin 3 (IL-3) receptors and is responsible for cell signaling.8,9 IL-5 receptor alpha (IL-5Rα) is expressed on human eosinophil and basophil progenitors in bone marrow as well as on mature circulating and tissue eosinophils and basophils. It plays an important role in promoting growth, differentiation, and maturation of eosinophils in the bone marrow, along with their survival and activation in peripheral tissues.9

All these findings led to the consideration of IL-5 as a potential target for severe, difficult to treat, eosinophilic asthma. Two main approaches were evaluated against the action of IL-5 on eosinophil-mediated inflammation. The first one was to block the circulating cytokine, and the second was to interfere with the IL-5Rα on eosinophils. Both anti-IL5 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (mepolizumab and reslizumab) and anti-IL5Rα (benralizumab) had been shown to reduce circulating eosinophils and improve asthma control in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma, in particular in patients with elevated eosinophilic blood count at baseline.10

Despite its clinical effectiveness, some studies highlighted that mepolizumab administration resulted in increased IL-5Rα expression and IL-5 local production, suggesting a kind of endogenous auto-regulatory pathway. Eosinophil persistence that has sometimes been detected during IL-5 mAbs treatment in clinical studies may be explained by the action of other cytokines, including IL-3 and GM-CSF, converging on IL-5 receptor and involved in eosinophil migration and activation despite soluble IL-5 blocking.11,12 Moreover, the formation of immune complexes between IL-5 and mepolizumab could act as an IL-5 reservoir leading to an incomplete or less sustained response to therapy.13

Benralizumab is a fully humanized afucosylated IgG1κ mAb that binds to an epitope on IL-5Rα, and inhibits IL-5 signaling, independently of the ligand presence.14 (Figure 1). Thanks to its restricted expression on human eosinophils and basophils and their progenitors in the bone marrow, IL-5Rα represents an ideal target for specific cell depletion.15 Benralizumab also induces antibody-directed cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) of eosinophils and basophils and, consequently, depletes IL-5Rα-expressing cells. In fact, afucosylation of the oligosaccharide core of human IgG1 has previously been shown to result in a 5–50-fold higher affinity to human Fcγ receptor IIIa (FcγRIIIa), expressed on natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and neutrophils.16 Therefore, afucosylation enhances the interaction between benralizumab and FcγRIIIa and improves ADCC functions (Figure 1). As a result, a total depletion of eosinophils in the bone marrow and blood, and an almost complete depletion in sputum and tissues (90% and 96%, respectively) can be observed.17 According to the current evidence, this aspect is very unique of benralizumab mechanism of action. Furthermore the sustained depletion of eosinophils makes benralizumab action independent of IL-5 levels, which can increase during asthma exacerbation, decreasing IL-5 mAbs effectiveness.18

In phase 1 and 2 randomized controlled studies on patients with sputum eosinophils ≥2%, benralizumab 30 mg SC showed a significant reduction not only of blood eosinophils, but also of inflammatory biomarkers such as derived neurotoxin (EDN) and eosinophil cationic protein (ECP).19

Basophils are also associated with inflammation, asthma severity, and exacerbations. In vitro studies have demonstrated that basophils constitutively express IL-5Rα but do not require IL-5 for their survival.16 Benralizumab potently induces basophil apoptosis in vitro, even though no significant data are available for in-vivo studies due to median low count of basophils at baseline in patients recruited in clinical studies.11,14

A proteomic analysis approach showed that benralizumab is able to significantly reduce (FDR <0.05) in the expression of: genes associated with eosinophils and basophils homeostasis, such as CLC, IL-5Rα, and PRSS33; immune-signaling complex genes (FCER1A); G-protein–coupled receptor genes (HRH4, ADORA3, P2RY14); and immune-related genes (ALOX15 and OLIG2).20

Efficacy issues: expected outcomes in practice

Similarly to other biological drugs, benralizumab has first been evaluated as an add on therapy for severe uncontrolled asthma, with the aim to reduce exacerbations and daily oral corticosteroids (OCS) dose in steroid dependent patients.21,22 The first clinical trial21 demonstrated that benralizumab treatment significantly impacted on exacerbation rate in the active group. In detail, it was a randomized, controlled, double-blind, dose-ranging phase 2b study which investigated the subcutaneous administration of 2 mg, 20 mg, or 100 mg of benralizumab vs placebo in patients with eosinophilic asthma. By selecting patients with at least 300 cells/μL in the blood, the administration of benralizumab at the dose of 20 and 100 mg resulted in reducing exacerbations compared with placebo (0.30 vs 0.68, reduction 57%, 80% CI=33–72, p=0.015 for 20 mg dose; 0.38 vs 0.68, difference 43%, 80% CI=18–60, p=0.049 for 100 mg dose). CALIMA and SIROCCO confirmed the efficacy of benralizumab by showing consistent exacerbation rate reductions in patients with high eosinophil counts.23,24 As mentioned above, the OCS sparing effect of benralizumab represented the other main endpoint that was evaluated in clinical trials. The ZONDA study specifically addressed the reduction of OCS intake in patients treated with benralizumab. A 75% median reduction of OCS dose was shown in patients who received benralizumab compared to the placebo group, which showed a reduction of 25% (p<0.001).25 Besides a reduction of exacerbations and systemic steroid dose, in the main studies a significant effect on lung function was also observed. In fact, the BISE study demonstrated that benralizumab treatment was able to obtain an improvement of pre-bronchodilator FEV1 greater than 80 mL (95% CI=0–150; p=0·04) after 3 months of therapy; on the other hand, no significant change was detected in the placebo treated patients.26

When comparing benralizumab to the other currently marketed anti IL-5 biologics, namely mepolizumab and reslizumab, poor evidence is available. An indirect treatment comparison, relying on literature data summarized in a Cochrane review, was recently published.27 As a main result it highlighted the superiority of mepolizumab in reducing clinically significant exacerbations and asthma control in comparison with reslizumab and benralizumab in patients with comparable levels of blood eosinophilia. Bourdin et al10 recently published a similar analysis, actually showing quite different results. They performed a matching-adjusted indirect comparison between benralizumab, mepolizumab, and reslizumab. Similar outcomes were described for benralizumab and mepolizumab in terms of reduction of the overall exacerbation rate (52% and 49%, respectively) in comparison with placebo (rate ratio [RR]=0.94, 95% CI=0.78–1.13, n=1,524). Both benralizumab and mepolizumab decreased by 52% (RR=1.00, 95% CI=0.57–1.75; n=1,524) the percentage of clinically significant and severe exacerbations. Also the impact on pre-bronchodilator FEV1 was similar. A comparison between benralizumab and reslizumab was excluded from the analysis due to the different clinical characteristics of the population evaluated in both studies. In fact, a systematic matching-adjusted comparative analysis was not applicable. However, through an indirect comparison of the final treatment outcomes, a similar overall efficacy of benralizumab and reslizumab was described.

Table 1 provides a summary of clinical characteristics of current market available anti-IL-5 mAbs.

Table 1.

Anti-IL-5 at a glance comparison

| Drug | Administration route | Regimen | Target population | Main clinical peculiarities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benralizumab | Subcutaneous | 30 mg every 4 weeks for the first 3 doses, then every 8 weeks | Eosinophilic asthma ≥300 cells/µL, CRSwNP | High affinity for IL-5 receptor and ADCC activity, eosinophils sustained tissue depletion, improvement of pulmonary function even in patients with FAO, steroid sparing effect |

| Mepolizumab | Subcutaneous | 100 mg every 4 weeks | Eosinophilic asthma ≥300 cells/µL | Excellent safety profile, steroid sparing effect |

| Reslizumab | Intravenous | 3 mg Kg−1 every 4 weeks | Eosinophilic asthma ≥400 cells/µL, CRSwNP | Personalized dose, improvement of pulmonary function |

Abbreviations: ADCC, Antibody-Dependent Cell Cytotoxicity; CRSwNP, Chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis; FAO, Fixed airway obstruction; IL-5Rα, Interleukin-5 receptor alpha subunit.

Of note, not negligible methodological limitations have to be considered when interpreting the results of an indirect comparison analysis, as suggested by the quite different results reported by the above-mentioned comparative studies. In fact, head-to-head studies would be required in order to obtain more reliable data. Furthermore, the evidence coming from the clinical trials certainly provides the basis for the use of these drugs in the real world. However, it is well known that substantial differences may occur between randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and real word studies, especially in terms of patients’ characteristics and follow-up and monitoring modality, which may impact on the drug effectiveness.

In addition to the need for identifying patient's responder profile, the steroid sparing effect, reduction in exacerbation rate, and improvement in lung function shown in patients treated with benralizumab need to be verified in the real-world scenario outside of randomized, controlled trials.28–30

Safety issues: eosinophils depletion and beyond

The safety profile of benralizumab is certainly one of the most discussed issues related to the use of the drug in clinical practice. In fact, the almost complete depletion of eosinophils in serum and in the bone marrow may raise some concerns and is currently under debate.31 Overall, reviewing the safety data of the published trials, it is possible to conclude that benralizumab administration was not related to serious adverse events, and its safety profile is similar to the other anti-IL-5 drugs.21–26 Fever, rhino-pharyngitis, muscle pain, and asthenia, although rare, were the most frequently reported side-effects during the trials course. More serious adverse events included herpes zoster, thyroid storm, and urticaria, of which onset was rare.31 The safety and tolerability of long-term benralizumab administration have recently been evaluated in the BORA study, published as an extension of CALIMA24 and SIROCCO.23 The main serious adverse events recorded during the study time frame were: worsening of asthma (3–4%), pneumonia (<1–1%), and bacterial pneumonia (0–1%).32 As far as neoplasias are concerned, 1% of patients enrolled in BORA had new malignancies, with only one (prostate cancer in Q8W administration) which was considered drug related by physicians. Notwithstanding this observation, a longer period of observation is necessary to completely exclude or warn about cancer risk, as already done for omalizumab.33,34 Although the results about safety in clinical trials are encouraging, even those in the long-term assessment, what can happen by reducing the number of eosinophils so drastically deserves to be monitored overtime. In order to hypothesize a safety expectation of benralizumab in the real world, we can rely as well on the data already described. No evidence of abnormalities related to eosinophil reduction have been reported from data regarding patients with immunodeficiency disorders. Furthermore, in a lab experimental setting with eosinophil-deficient mice, no health failure or particular syndromes have been observed, allowing us to hypothesize that eosinophils could not play a critical role in the well-being and homeostasis of mammals.35 Notwithstanding these observations, the most relevant data concerning the long-term safety of this drug will be obtained after a longer period of use, and collected from the data related to post-marketing pharmaco-vigilance. Monitoring the benralizumab safety profile in the real word setting is mandatory. In fact, common conditions such as smoke, old age, or multi-drug regimens represent exclusion criteria for clinical trials and may impact on the drug safety profile.

Target population: potential predictors of efficacy

When considering the prescription requirements of the currently available anti IL-5 mAbs (Table 1), a not negligible overlapping area in terms of target population potentially emerges. Overall, in the absence of biomarkers specifically predicting the good clinical response to each biologic drug, the patient selection process still represents a critical issue.5

In the context of a pooled analysis of data from SIROCCO23 and CALIMA24 studies, Bleecker et al36 identified some baseline clinical features associated to a better clinical response to benralizumab. A level of blood eosinophils ≥300 μL−1, OCS use, history of nasal polyposis, and FVC <65% of predicted represented predictors of enhanced benralizumab efficacy. Similarly, FitzGerald et al37 explored the clinical response to benralizumab with respect to different patients’ characteristics before the treatment start. A pooled analysis of the results from SIROCCO and CALIMA was performed. As a main finding, a greater improvement in annual exacerbation rate was observed in the presence of a combination of increased blood eosinophil thresholds and a history of three or more exacerbations per year at baseline. Furthermore, even in patients with fixed airflow obstruction and obesity, a significant improvement of lung function has been observed during benralizumab treatment course.38 Benralizumab also demonstrated a greater steroid-sparing effect in comparison with other anti IL-5 drugs.4

The results reported above can be helpful in identifying the best responder patients to benralizumab and suggest that, up to now, in the absence of univocal biomarkers predictive of good clinical response, considering the patient’s characteristics, including lung function, asthma exacerbations, nasal polyposis, ongoing dose of OCS, is of utmost relevance in the treatment selection process.

As a step forward, the definition of the responder profile for each of the available biological treatment options, maybe through head-to-head comparative studies, will potentially support even more the pathway to precision medicine and the critical matching of the right drug with the right patient. The analysis of non-responder patients in the real world will also be essential in achieving the goal.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Varsano S, Segev D, Shitrit D. Severe and non-severe asthma in the community: a large electronic database analysis. Resp Med. 2017;123:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S, Golam S, Myers J, et al. Systematic literature review of the clinical, humanistic, and economic burden associated with asthma uncontrolled by GINA steps 4 or 5 treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;16:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hekking PP, Wener RR, Amelink M, et al. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menzella F, Bertolini F, Biava M, et al. Severe refractory asthma: current treatment options and ongoing research. Drugs Context. 2018;7:212561. doi: 10.7573/dic.212561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caminati M, Senna G. Uncontrolled severe asthma: starting from the unmet needs. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:175–177. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2018.1528218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bousquet J, Chanez P, Lacoste JY, et al. Eosinophilic inflammation in asthma. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1033–1039. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199010113231505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caminati M, Pham DL, Bagnasco D, Canonica GW. Type 2 immunity in asthma. World Allergy Organ J. 2018;11:13. doi: 10.1186/s40413-018-0192-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menzella F, Zucchi L, Taddei S, Lusuardi M, Galeone C. Profile of anti-IL-5 mAb mepolizumab in the treatment of severe refractory asthma and hypereosinophilic diseases. J Asthma Allergy. 2015;8:105–114. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S40244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matera MG, Calzetta L, Rinaldi B, Cazzola M. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic drug evaluation of benralizumab for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:1007–1013. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1359253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bourdin A, Husereau D, Molinari N, et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of benralizumab versus interleukin-5 inhibitors for the treatment of severe asthma: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(5). Print 2018 Nov. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01393,2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laviolette M, Gossage DL, Gauvreau G, et al. Effects of benralizumab on airway eosinophils in asthmatic patients with sputum eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1086–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stein ML, Villanueva JM, Buckmeier BK, et al. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy reduces eosinophil activation ex vivo and increases IL-5 and IL-5 receptor levels. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1473–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukherjee M, Lim HF, Thomas S, et al. Airway autoimmune responses in severe eosinophilic asthma following low-dose Mepolizumab therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2017;13:2. doi: 10.1186/s13223-016-0174-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolbeck R, Kozhich A, Koike M, et al. MEDI-563, a humanized anti-IL-5 receptor α mAb with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1344–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan L, Gódor D, Bratt J, Kenyon NJ, Louie S. Benralizumab: a unique IL-5 inhibitor for severe asthma. J Asthma Allergy. 2016;9:71–81. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S78049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinkawa T, Nakamura K, Yamane N, et al. The absence of fucose but not the presence of galactose or bisecting N-acetylglucosamine of human IgG1 complex-type oligosaccharides shows the critical role of enhancing antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3466–3473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210665200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghazi A, Trikha A, Calhoun WJ. Benralizumab – a humanized mAb to IL-5Rα with enhanced antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity – a novel approach for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:113–118. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.642359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshimura-Uchiyama C, Yamaguchi M, Nagase H, et al. Comparative effects of basophil-directed growth factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;12:113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham TH, Damera G, Newbold P, Ranade K. Reductions in eosinophil biomarkers by benralizumab in patients with asthma. Respir Med. 2016;111:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sridhar S, Liu H, Pham TH, Damera G, Newbold P. Modulation of blood inflammatory markers by benralizumab in patients with eosinophilic airway diseases. Respir Res. 2019;20:14. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1030-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castro M, Wenzel SE, Bleecker ER, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, versus placebo for uncontrolled eosinophilic asthma: A phase 2b randomised dose-ranging study. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:878–890. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70201-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowak RM, Parker JM, Silverman RA, et al. A randomized trial of benralizumab, an antiinterleukin 5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, after acute asthma. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, Chanez P, et al.; SIROCCO study investigators. Efficacy and safety of benralizumab for patients with severe asthma uncontrolled with high-dosage inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting β2-agonists (SIROCCO): a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2115–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31324-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2128–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31322-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Oral glucocorticoid–sparing effect of benralizumab in severe asthma. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2017;376(25):2448–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson GT, FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, et al. Benralizumab for patients with mild to moderate, persistent asthma (BISE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(7):568–576. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30234-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busse W, Chupp G, Nagase H, et al. Anti-IL-5 treatments in patients with severe asthma by blood eosinophil thresholds: indirect treatment comparison. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):190,200.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bagnasco D, Milanese M, Rolla G, et al. The North-Western Italian experience with anti IL-5 therapy amd comparison with regulatory trials. World Allergy Organ J. 2018;11(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s40413-018-0210-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caminati M, Senna G, Guerriero M, et al. Omalizumab for severe allergic asthma in clinical trials and real-life studies: what we know and what we should address. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2015;31:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Battaglia S, Basile M, Spatafora M, Scichilone N. Are asthmatics enrolled in randomized trials representative of real-life outpatients?Respiration. 2015;89: 383-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bagnasco D, Caminati M, Ferrando M, et al. Anti-IL-5 and IL-5Ra: efficacy and safety of new therapeutic strategies in severe uncontrolled asthma. Biomed Res Int. 2018;.5:5698212.doi: 10.1155/2018/5698212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busse WW, Bleecker ER, FitzGerald JM, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of benralizumab in patients with severe, uncontrolled asthma: 1-year results from the BORA phase 3 extension trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7:46–59. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30406-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung KF. 2-year safety and efficacy results for benralizumab. Lancet Respir Med [Internet] 2019;7(1):5–6. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30468-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Long A, Rahmaoui A, Rothman KJ, et al. Incidence of malignancy in patients with moderate-to-severe asthma treated with or without omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:560–567.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gleich GJ, Klion AD, Lee JJ, Weller PF. The consequences of not having eosinophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;68:829–835. doi: 10.1111/all.2013.68.issue-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bleecker ER, Wechsler ME, FitzGerald JM, et al. Baseline patient factors impact on the clinical efficacy of benralizumab for severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(4):pii: 1800936. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01675-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Predictors of enhanced response with benralizumab for patients with severe asthma: pooled analysis of the SIROCCO and CALIMA studies. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(1):51–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30344-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chipps BE, Hirsch I, Trudo F, et al. Demographics, clinical characteristics, and response to benralizumab treatment for patients with severe, eosinophilic asthma and fixed airflow obstruction. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:A2489. [Google Scholar]