Abstract

Tooth pain is a common presentation in primary care, with 32.4% of Singaporeans experiencing pain from dental caries in their lifetime. Some systemic conditions can have oral presentations, and oral conditions may be associated with chronic disease. A good history and examination is key in delineating odontogenic from non-odontogenic causes of tooth pain. Primary care physicians should accurately diagnose and assess common dental conditions and make appropriate referrals to the dentist. Common non-odontogenic causes of orofacial pain can be mostly managed in primary care, but important diagnoses such as acute coronary syndrome, peritonsillar abscess and temporal arteritis must not be missed. Ibuprofen has been shown to be effacious, safe and cost-effective in managing odontogenic pain. Antibiotics are indicated when there is systemic or local spread of dental infection. Without evidence of spread, antibiotics have not been shown to reduce pain or prevent subsequent dental infections.

Keywords: dental care, facial pain, general practice, primary health care, toothache

Mr Tan, a 48-year-old banker with no significant past medical history, visited your clinic with the complaint of severe right-sided tooth pain that radiated to the right temporal region of the head. The pain was excruciating and had affected his concentration at work. The over-the-counter paracetamol he had taken did not seem to relieve the pain and Mr Tan felt that it could not just be a simple toothache. He asked you to prescribe some antibiotics to treat what he believed was a dental infection.

WHAT IS TOOTH PAIN?

Tooth pain, which is often known as toothache, refers to the symptom of pain arising from the tooth (or teeth).

HOW COMMON IS THIS IN MY PRACTICE?

Dental caries (Fig. 1) is a common dental condition. Globally, up to 35% of people have untreated dental caries,(1) and an estimated 32.4% of the Singapore population will experience pain from symptomatic dental caries in their lifetime.(2) Locally, oral disease is ranked 16th in terms of years lost to disability and has been an important cause of functional and social impairment.(2) Other common causes of tooth pain include periodontal disease and dental trauma. Patients often seek the opinion of their family doctors for their tooth pain.

Fig. 1.

Photograph shows dental caries in a patient, with visible tooth decay (arrows).

HOW IS THIS RELEVANT TO MY PRACTICE?

Primary care physicians are well placed to help patients presenting with tooth pain at their clinics for a number of reasons: they provide opportunistic general and dental health promotion advice, manage a number of causes of orofacial pain, and diagnose systemic conditions that have oral presentations. Primary care physicians need to keep in mind how chronic conditions and lifestyle factors may relate to oral conditions. For instance, patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus have a threefold increased risk of developing periodontitis (Fig. 2).(3) Smoking and alcohol consumption increase the risk of oropharyngeal cancers, and patients with osteoporosis on long-term bisphosphonates or RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand) inhibitors such as denosumab are at increased risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.(4)

Fig. 2.

Photograph shows a patient with periodontitis characterised by gingival recession (arrow).

In turn, oral conditions may be associated with chronic conditions. For example, poor oral hygiene increases the risk of infective endocarditis-related bacteraemia after tooth brushing by three- to fourfold.(5) In addition, conditions such as oral candidiasis may point to the underlying immunosuppression seen in HIV infection.(6) This bidirectional relationship underscores the pivotal role that primary care physicians play in the prompt diagnosis, investigation and management of patients with oral conditions.

WHAT CAN I DO IN MY PRACTICE?

Clinical history and examination

Many oral conditions may mimic tooth pain and it is important to delineate the different causes with history-taking and examination. We suggest the following:

Identify the source of pain by taking a comprehensive pain history.

Check for fever and signs of spread (e.g. local swelling or cervical lymphadenopathy).

Examine the oral cavity (i.e. tonsils, palate, tongue and ulcers).

Examine the dentition and gums, specifically looking out for dental caries (Fig. 1), gingival oedema and abscesses, loose or broken fillings, ill-fitting dentures, and tooth mobility.

Screen for other possible causes of non-odontogenic pain (e.g. temporomandibular joint, eyes, sinuses, ears, and the parotid and submandibular glands).

Diagnosis and management

The key decision point in managing patients with tooth pain is determining whether the pain is odontogenic or non-odontogenic in origin.

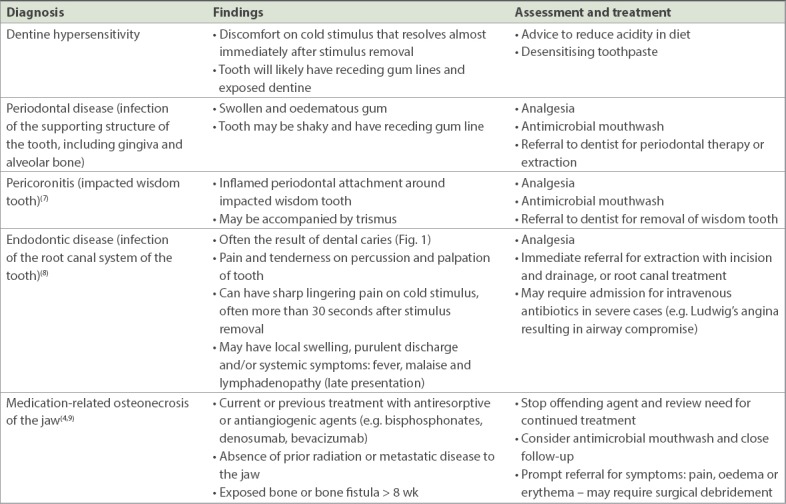

Odontogenic pain

Odontogenic pain, or pain arising from the tooth, may be recognised by the following characteristics: it is often localised to the tooth, has an excruciating and acute onset, and is exquisitely sensitive to hot or cold stimulus. It may be aggravated by biting or chewing, is typically associated with dental caries or dental trauma (look for chipped surfaces or lacerated gingival tissues) and may sometimes be due to periodontal disease. In general, patients with odontogenic pain should be referred to a dentist. A summary of the common causes of odontogenic pain seen in primary care are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Causes of odontogenic pain.

Non-odontogenic pain

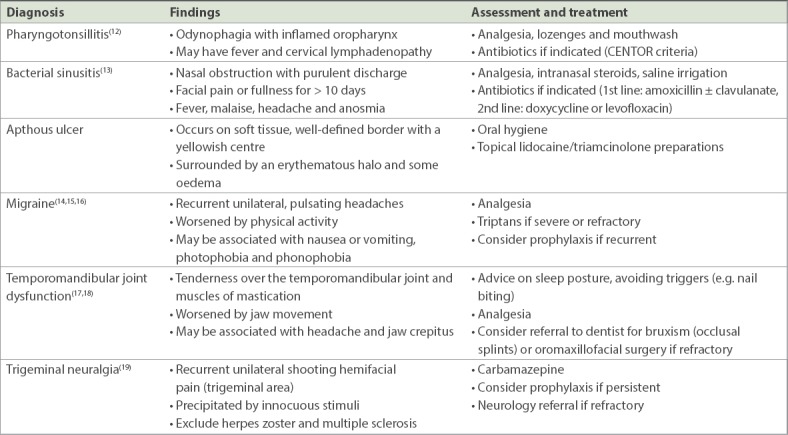

Non-odontogenic pain refers to tooth pain that does not arise from the tooth. As there are many non-odontogenic causes of tooth pain, an exhaustive list is beyond the scope of this article and more comprehensive resources are recommended.(10,11) Nonetheless, the primary care physician needs to consider the following red flags in patients who seem to present with tooth pain: (a) acute coronary syndrome – presenting with radiation of pain to the jaw; (b) peritonsillar abscess – presenting with odynophagia, trismus and hoarseness; and (c) temporal arteritis – presenting with temporal headache, visual defects, jaw claudication, or neck and shoulder stiffness.

Common non-odontogenic causes of orofacial pain seen in primary care are highlighted in Table II. Most of these may be easily diagnosed and managed in primary care.

Table II.

Causes of non-odontogenic orofacial pain.

Prescribing analgesia for odontogenic pain

Paracetamol and short-acting non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) form the mainstay of pain management. Ibuprofen has been shown to have good efficacy and safety, and is cost-effective.(20) Opioid alternatives such as tramadol, which carries the risk of dependency and other side effects, may be carefully considered if required. Antimicrobial mouthwash can be useful for osteonecrosis of the jaw and pericoronitis (i.e. impacted wisdom tooth).

The role of antibiotics in odontogenic pain

A Cochrane review recommends that antibiotics are indicated when there is clinical evidence of systemic (e.g. fever or malaise) or local spread of dental infection (e.g. cellulitis, lymphadenopathy or diffused swelling).(21) In such instances, antibiotics with coverage of oral bacteria such as a penicillin with beta-lactamase inhibitor or metronidazole may be prescribed.(22) Antibiotics have a limited role in the treatment of dental infection without spread: the evidence has not shown that antibiotics reduce pain(23) or prevent subsequent dental infections(24) when there is no evidence of spread. Instead, inappropriate use of antibiotics risks resulting in antimicrobial resistance and has adverse effects with minimal benefit to patients. Despite this, the reported rate of antibiotic prescription in primary care patients with odontogenic pain in the United Kingdom has been disproportionately high at 57%.(25)

In summary, a safe approach to clinical decision-making in patients presenting with tooth pain entails careful differentiation between odontogenic versus non-odontogenic pain, keeping in mind the possibility of underlying red flags. Management decision-making includes the use of simple analgesics, antibiotics only when clinically indicated, and prompt dental or specialist referral when required.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

The first step in managing tooth pain is to differentiate between odontogenic and non-odontogenic pain with a detailed history and clinical examination of the oral cavity.

Keep in mind red flags that may cause non-odontogenic pain, such as acute coronary syndrome, peritonsillar abscess and temporal arteritis.

Management of odontogenic pain includes relief of symptoms and, when required, timely referral to the dentist for assessment, tests and treatment.

Analgesia such as paracetamol and NSAIDs (e.g. ibuprofen 400 mg three times daily) is preferred.

Antibiotics are only indicated if clinical evidence of local or systemic spread of dental infections is present.

On further assessment, you determined that Mr Tan’s pain was odontogenic. There was tenderness on percussion of the upper right first molar, a sharp shooting pain on cold stimulus, and lingering of the pain for almost one minute after the cold was removed, suggesting possible endodontic disease. Without evidence of systemic or local spread of infection, you explained that Mr Tan did not need antibiotics. Instead, you suggested that it would be beneficial to see a dentist for assessment and possible root canal treatment. You added ibuprofen to his prescription and arranged a referral to the dentist for the following day.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010:a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92:592–7. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epidemiology &Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health Singapore. Singapore Burden of Disease Study 2010. [Accessed May 22 2018]. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider5/resources-statistics/reports/singapore-burden-of-disease-study-2010-report_v3.pdf .

- 3.Ryan ME, Carnu O, Kamer A. The influence of diabetes on the periodontal tissues. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:34S–40S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan BH, Yee R, Puvanendran R, Ang SB. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in osteoporotic patients:prevention and management. Singapore Med J. 2018;59:70–5. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2018014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, et al. Poor oral hygiene as a risk factor for infective endocarditis-related bacteremia. J Ame Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1238–44. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alpert PT. Oral health:the oral-systemic health connection. Home Health Care Manag. 2017;1:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blakey GH, White RP, Jr, Offenbacher S, et al. Clinical/biological outcomes of treatment for pericoronitis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:1150–60. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(96)90339-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glickman GN, Schweitzer JL. Endodontic Diagnosis. Endodontics:Colleagues for Excellence 2013 [online] [Accessed May 22 2018]. Available at: https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/07/endodonticdiagnosisfall2013.pdf .

- 9.Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw--2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;72:1938–56. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scrivani SJ, Spierings EL. Classification and differential diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial pain. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016;28:233–46. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:1381–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, Vanjaka A, Low DE. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA. 2004;291:1587–95. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.13.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, et al. Clinical practice guideline (update):adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152(2 Suppl):S1–S39. doi: 10.1177/0194599815572097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults:the american headache society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache. 2015;55:3–20. doi: 10.1111/head.12499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee VME, Ang LL, Soon DTL, Ong JJY, Loh VWK. The adult patient with headache. Singapore Med J. 2018;59:399–406. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2018094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, et al. Diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders (DC/TMD) for clinical and research applications:recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2014;28:6–27. doi: 10.11607/jop.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mujakperuo HR, Watson M, Morrison R, Macfarlane TV. Pharmacological interventions for pain in patients with temporomandibular disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD004715. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004715.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gronseth G, Cruccu G, Alksne J, et al. Practice parameter:the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review):report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies. Neurology. 2008;71:1183–90. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000326598.83183.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pozzi A, Gallelli L. Pain management for dentists:the role of ibuprofen. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2011;2(3-4 Suppl):3–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cope AL, Chestnutt IG, Wood F, Francis NA. Dental consultations in UK general practice and antibiotic prescribing rates:a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e329–36. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X684757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cope A, Francis N, Wood F, Mann MK, Chestnutt IG. Systemic antibiotics for symptomatic apical periodontitis and acute apical abscess in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD010136. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010136.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oral and Dental Expert Group. eTG Version 2. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2012. Therapeutic guidelines:oral and dental. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Runyon MS, Brennan MT, Batts JJ, et al. Efficacy of penicillin for dental pain without overt infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1268–71. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agnihotry A, Fedorowicz Z, van Zuuren EJ, Farman AG, Al-Langawi JH. Antibiotic use for irreversible pulpitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD004969. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004969.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.