Ceftriaxone has a higher biliary elimination than cefotaxime (40% versus 10%), which may result in a more pronounced impact on the intestinal microbiota. We performed a monocenter, randomized open-label clinical trial in 22 healthy volunteers treated by intravenous ceftriaxone (1 g/24 h) or cefotaxime (1 g/8 h) for 3 days.

KEYWORDS: cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, intestinal microbiota, metagenomics, pharmacokinetics

ABSTRACT

Ceftriaxone has a higher biliary elimination than cefotaxime (40% versus 10%), which may result in a more pronounced impact on the intestinal microbiota. We performed a monocenter, randomized open-label clinical trial in 22 healthy volunteers treated by intravenous ceftriaxone (1 g/24 h) or cefotaxime (1 g/8 h) for 3 days. We collected fecal samples for phenotypic analyses, 16S rRNA gene profiling, and measurement of the antibiotic concentration and compared the groups for the evolution of microbial counts and indices of bacterial diversity over time. Plasma samples were drawn at day 3 for pharmacokinetic analysis. The emergence of 3rd-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli (Enterobacterales), Enterococcus spp., or noncommensal microorganisms was not significantly different between the groups. Both antibiotics reduced the counts of total Gram-negative enteric bacilli and decreased the bacterial diversity, but the differences between the groups were not significant. All but one volunteer from each group exhibited undetectable levels of antibiotic in feces. Plasma pharmacokinetic endpoints were not correlated to alteration of the bacterial diversity of the gut. Both antibiotics markedly impacted the intestinal microbiota, but no significant differences were detected when standard clinical doses were administered for 3 days. This might be related to the similar daily amounts of antibiotics excreted through the bile using a clinical regimen. (This study has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifier NCT02659033.)

TEXT

The rise in bacterial resistance to antibiotics, particularly that of Gram-negative bacteria, constitutes a serious threat to our medical system (1). Initially restrained to nosocomial infections, antibiotic resistance has spread worldwide (2), affecting treatment of community-acquired infections. One of the drivers of this evolution is the impact that antibiotics, in particular, beta-lactams, exert on the intestinal commensal microbiota of both humans and animals (3).

In their studies of healthy volunteers receiving 5-day courses of ciprofloxacin, Dethlefsen and colleagues observed that antibiotic administration had a rapid effect in reducing bacterial diversity and in modifying the gut microbiome composition (4, 5). Similar observations were reported with moxifloxacin (6). These results are a strong incentive to better document the impact of antibiotics on the gut microbiome (7) and to identify the drivers of its disruption. Indeed, the gut microbiome has been shown to contribute to health maintenance of its host (8).

A limited number of studies have suggested that taking into account antibiotic pharmacokinetic characteristics might help to reduce the impacts of antibiotics on the microbiome. The two 3rd-generation cephalosporins ceftriaxone and cefotaxime share their antibacterial spectra, indications, and intravenous administration route, but they have different pharmacokinetic characteristics: ceftriaxone is administered once daily and has a 40% biliary elimination, while cefotaxime needs thrice daily administration but has a 10% biliary elimination. In two randomized controlled trials, female patients requiring gynecological surgery received a single high-dose (2 g of ceftriaxone or 2 g of cefotaxime) antibiotic prophylactic treatment (9, 10). Both studies suggested a more pronounced impact of ceftriaxone on the gut microbiota in terms of the selection of Gram-negative enteric bacillus populations resistant to 3rd-generation cephalosporins. Similar trends were reported in observational studies (11, 12).

However, no study dealing with usual antibiotic regimens administered in clinical practice is available. Indeed, cefotaxime is usually administered at higher daily doses than ceftriaxone, which may ultimately lead to quite similar effects on the gut microbiota. Moreover, next-generation sequencing methods were not used to investigate this question but may provide a precise description of the microbiome.

Here, we report the results of a prospective randomized clinical trial performed in healthy volunteers receiving a clinical course of ceftriaxone or cefotaxime for 3 days for the comparison of their impact on the gut microbiota, determined using phenotypic analysis and 16S rRNA gene profiling.

RESULTS

Subjects.

Thirty-three subjects were screened, and 22 subjects were randomized (11 in each treatment group); all participated in the trial until the end of follow-up. Their baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. No serious adverse event was reported, but treatment was stopped early in one subject in the cefotaxime group who presented a vasovagal malaise while the intravenous line was being placed for the 8th infusion.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 22 included subjectsa

| Characteristic | Value for subjects treated with: |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone (n = 11) | Cefotaxime (n = 11) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| No. (%) of men | 2 (18) | 4 (36) |

| Median (min, max) age (yr) | 30 (24, 55) | 24 (18, 61) |

| Median (min, max) total body wt (kg) | 72.0 (57.9, 78.4) | 63.4 (49.9, 87.0) |

| Median (min, max) body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.6 (20.0, 28.7) | 22.0 (18.6, 28.9) |

| Median (min, max) count of microorganisms in feces at baseline (log10 CFU/g) | ||

| Resistant enterobacteria (AES agar) | <2.0 (<2.0, 5.4) | <2.0 (<2.0, 2.8) |

| Resistant enterobacteria (ChromID ESBL agar) | <2.0 (<2.0, 5.7) | <2.0 (<2.0, <2.0) |

| Total enterobacteria | 7.7 (5.8, 8.7) | 7.8 (3.3, 9.1) |

| Enterococcus spp. | 6.2 (3.4, 9.2) | 6.7 (3.3, 7.8) |

| S. aureus | <2.0 (<2.0, 4.2) | <2.0 (<2.0, 3.0) |

| P. aeruginosa | <2.0 (<2.0, 5.1) | <2.0 (<2.0, 2.7) |

| C. difficile | <2.0 (<2.0, <2.0) | <2.0 (<2.0, <2.0) |

| Yeasts | <2.0 (<2.0, 2.7) | <2.0 (<2.0, 2.4) |

| Median (min, max) index of α-diversity at day −1 | ||

| Shannon index | 3.9 (3.2, 4.3) | 4.0 (2.8, 4.3) |

| No. of OTUs | 451 (308, 591) | 451 (267, 521) |

| Median (min, max) index of β-diversity between day −1 and day −15 | ||

| Bray-Curtis dissimilarity | 0.35 (0.23, 0.51) | 0.29 (0.17, 0.52) |

| Unweighted UniFrac distance | 0.41 (0.32, 0.46) | 0.38 (0.29, 0.49) |

| Median (min, max) relative abundance (%) of the main bacterial phyla at day −1 | ||

| Actinobacteria | 4.7 (1.3, 13.5) | 4.3 (2.1, 10.0) |

| Bacteroidetes | 34.1 (23.2, 52.2) | 40.2 (24.2, 60.4) |

| Firmicutes | 55.7 (43.9, 69.1) | 54.1 (32.7, 68.2) |

| Proteobacteria | 0.9 (0.3, 1.6) | 0.6 (0.2, 7.4) |

| Other phyla | 1.2 (0.3, 2.6) | 1.4 (0.7, 3.2) |

Baseline counts of microorganisms were computed as the arithmetic mean of the log10 counts observed for the available pretreatment samples at days −15, −7, and −1. min, minimum; max, maximum.

Ceftriaxone and cefotaxime pharmacokinetics.

For both antibiotics, plasma pharmacokinetics were best described by a 2-compartment model with first-order elimination from the central compartment. All population parameters could be estimated with a reasonable precision (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and the goodness of fit was satisfactory (Fig. S1 and S2). Derived pharmacokinetic endpoints estimated for the 11 subjects included in each treatment group are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Derived pharmacokinetic endpoints of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime for the 11 subjects in each treatment group derived from the estimated individual pharmacokinetic parametersa

| Treatment | fAUC0–24,ss (mg · h/liter) | fCmax (mg/liter) | fCmin (mg/liter) | fT > 1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone (n = 11) | 83.8 (59.0, 105.3) | 13.5 (10.8, 14.9) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.5) | 94.2 (68.6, 100) |

| Cefotaxime (n = 11) | 121.5 (83.6, 187.0) | 40.6 (29.4, 55.9) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.2) | 53.0 (44.5, 66.7) |

The data represent the median (minimum, maximum).

All subjects exhibited undetectable concentrations of antibiotics in feces between day −1 and day 30, except for one subject in each treatment group. Subject 16 had detectable concentrations of ceftriaxone in feces between day 2 and day 7. The concentrations ranged from 5.0 μg/g to 93.7 μg/g, with the maximal value being measured at day 4. Subject 3 had detectable concentrations of cefotaxime in feces at day 4 (1.6 μg/g). These 2 subjects had derived pharmacokinetic endpoints close to the median values observed for their respective treatment groups.

Phenotypic analysis of the fecal samples.

Overall, 283 fecal samples were available for phenotypic analyses. The baseline counts of the microorganisms studied are presented in Table 1.

(i) Third-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli.

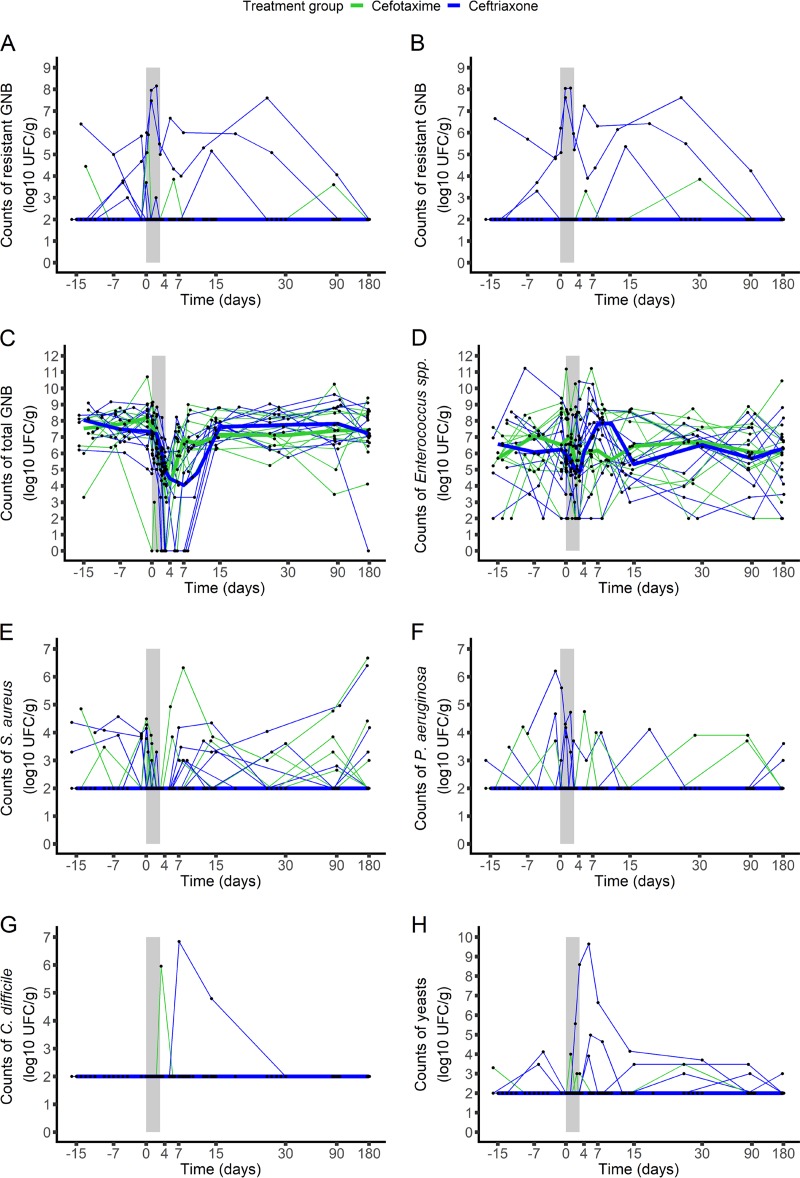

No major change in the counts of resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli was observed in either of the two treatment groups over time (Fig. 1 and Fig. S3A and B), and no significant difference was observed between groups (Table 3). The molecular characteristics of the detected resistant strains are presented in Table S2.

FIG 1.

Evolution of the counts of the studied microorganisms in the fecal samples from the 22 included subjects treated with ceftriaxone (n = 11, blue) or cefotaxime (n = 11, green). The studied microorganisms included 3rd-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli (measured on AES plates [A] or ChromID ESBL plates [B]), total Gram-negative enteric bacilli (C), Enterococcus spp. (D), S. aureus (E), P. aeruginosa (F), C. difficile (G), and yeasts (H). The light gray zone represents the treatment period. Thin lines represent individual values, and thick lines represent the median change from the baseline of the log10 counts at each time. UFC, number of colony-forming units; GNB, Gram-negative enteric bacilli.

TABLE 3.

AUC of variation from baseline of the counts of the studied microorganisms between baseline and day 7 or day 15 and of bacterial diversity indices between day −1 and day 30 in fecal samples from the 22 subjectsa

| Parameter | Value for subjects treated with: |

P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone (n = 11) | Cefotaxime (n = 11) | ||

| AUCD0D7 of raw bacterial counts (no. of log10 CFU · day/g) | |||

| Resistant enterobacteria (AES agar) | 0.0 (0.0, 23.4) | 0.0 (0.0, 2.7) | 0.40 |

| Resistant enterobacteria (ChromID ESBL agar) | 0.0 (0.0, 24.3) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.5) | 0.28 |

| AUCD0D7 of count change from baseline (no. of log10 CFU · day/g) | |||

| Total enterobacteria | −14.8 (−30.0, −7.0) | −11.2 (−26.0, −6.2) | 0.26 |

| Enterococcus spp. | −0.3 (−8.6, 2.6) | −0.9 (−3.5, 4.1) | 0.56 |

| S. aureus | 0.0 (−9.7, 1.3) | 0.0 (−2.7, 1.7) | 0.23 |

| P. aeruginosa | 0.0 (−8.4, 5.5) | 0.0 (−4.0, 2.9) | 0.87 |

| C. difficile | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 7.0) | 0.36 |

| Yeasts | 0.0 (−3.9, 18.4) | 0.0 (−2.5, 2.4) | 0.85 |

| AUCD0D15 of count change from baseline (no. of log10 CFU · day/g) | |||

| Resistant enterobacteria (AES agar) | 0.0 (−50.7, 40.3) | 0.0 (−12.2, 4.9) | >0.99 |

| Resistant enterobacteria (ChromID ESBL agar) | 0.0 (−6.5, 44.6) | 0.0 (0.0, 6.0) | 0.79 |

| Total enterobacteria | −30.7 (−79.2, −12.4) | −21.8 (−37.5, 16.4) | 0.088 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 7.6 (−38.1, 39.5) | 6.2 (−31.5, 19.3) | 0.75 |

| S. aureus | 1.2 (−18.5, 6.6) | 0.0 (−7.3, 21.2) | 0.82 |

| P. aeruginosa | 0.0 (−25.5, 13.6) | 0.0 (−8.4, 7.0) | 0.69 |

| C. difficile | 0.0 (0.0, 33.7) | 0.0 (0.0, 7.5) | >0.99 |

| Yeasts | 0.0 (−10.5, 53.7) | 0.0 (−6.5, 2.5) | 0.46 |

| AUCD−1D30 of change from baseline of diversity indices (unit · day) | |||

| Shannon diversity index | −12.0 (−26.6, 2.4) | −10.5 (−21.6, 15.1) | 0.85 |

| No. of OTUs | −1,391 (−5,708, 114) | −1,816 (−2,677, 907) | >0.99 |

| Bray-Curtis dissimilarity | 12.2 (10.3, 19.1) | 12.2 (10.7, 17.6) | 0.95 |

| Unweighted UniFrac distance | 12.1 (10.0, 18.7) | 12.5 (10.9, 16.9) | 0.75 |

Baseline counts were computed as the arithmetic mean of the log10 counts observed for pretreatment samples. AUCD0D15 and AUCD−1D30 were normalized by the actual time observed between baseline and day 15 and baseline and day 30, respectively. Data are presented as the median (minimum, maximum).

P values refer to the results of the nonparametric Wilcoxon test.

At baseline, colonization with resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli was detected in 5 subjects (45.5%) and 1 subject (9.7%) in the ceftriaxone and cefotaxime groups, respectively. Among the uncolonized subjects, 1 (16.7%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.4%, 64.1%) from the ceftriaxone group and 2 (20%; 95% CI, 2.5%, 55.6%) from the cefotaxime group acquired resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli between the beginning of treatment and day 15 (P > 0.99) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Emergence of 3rd-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli or noncommensal microorganisms of the intestinal tract between day 1 and day 15 in the 22 included subjectsa

| Microorganism | No. (%) of subjects treated with: |

P valueb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone |

Cefotaxime |

||||

| Subjects at risk | Subjects colonized | Subjects at risk | Subjects colonized | ||

| Resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli | 6 | 1 (16.7) | 10 | 2 (20) | >0.99 |

| S. aureus | 7 | 6 (85.7) | 8 | 3 (37.5) | 0.12 |

| P. aeruginosa | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 9 | 1 (11.1) | >0.99 |

| C. difficile | 11 | 1 (9.1) | 11 | 1 (9.1) | >0.99 |

| Yeasts | 9 | 3 (33.3) | 10 | 3 (30) | >0.99 |

Only subjects who were not colonized before the beginning of treatment were included in the analysis. For resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli, results from either AES or ChromID ESBL agar plates were considered for definition of the emergence of resistance.

P values refer to the result of a nonparametric Fisher’s exact test.

(ii) Other microorganisms studied.

No significant difference in the variation from baseline of any of the other microorganisms studied was observed between the groups (Table 3; Fig. 1; Fig. S3C to H). Both antibiotics profoundly reduced the counts of total Gram-negative enteric bacilli, with the highest median reduction from baseline being 4.4 log10 CFU/g (2.4, 8.7 log10 CFU/g [minimum, maximum]) in the ceftriaxone group and 3.8 (1.9, 8.1 log10 CFU/g [minimum, maximum]) in the cefotaxime group (Fig. 1 and Fig. S3C). At day 15, the counts of Gram-negative enteric bacilli returned to their baseline value. Carriage of toxigenic Clostridium difficile was detected in 3 patients, 1 (at day 10) in the ceftriaxone group and 2 (1 at day 4 and 1 at day 15) in the cefotaxime group (P > 0.99). Results regarding the emergence of other noncommensal microorganisms of the intestinal tract are presented in Table 4.

16S rRNA gene profiling of the fecal samples.

16S rRNA gene profiling was performed on 148 available samples. The baseline characteristics taxonomic composition and diversity indices are presented in Table 1.

(i) Taxonomic composition.

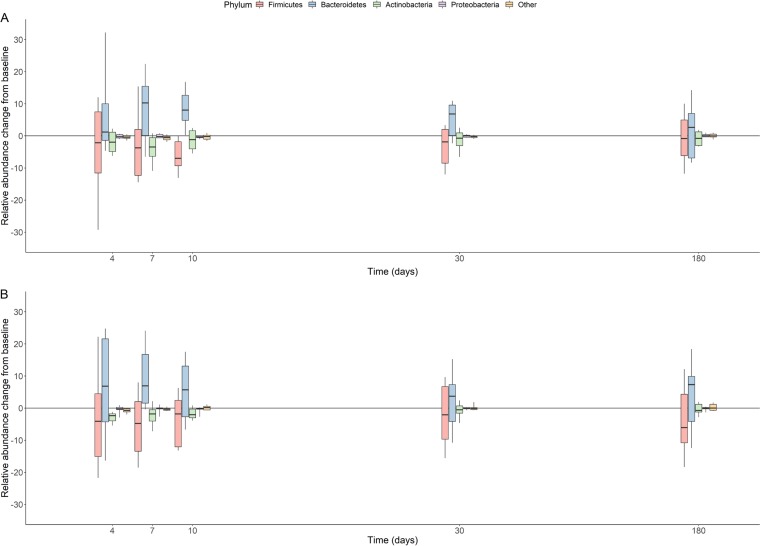

Both antibiotics reduced the relative abundance of the Firmicutes (median maximal change [minimum, maximum], −9.3% [−47.6%, 2.2%] in the ceftriaxone group and −12.3% [−22.4%, −4.0%] in the cefotaxime group), of the Actinobacteria (median maximal change [minimum, maximum], −3.6% [−11.0%, 0.0%] in the ceftriaxone group and −2.3% [−8.9%, −0.1%] in the cefotaxime group), and of Bacteroidetes (median maximal change [minimum, maximum], −2.2% [−31.4%, 10.8%] in the ceftriaxone group and −4.0% [−23.8%, 15.2%] in the cefotaxime group). The relative abundance of the Proteobacteria remained roughly unchanged (median maximal change [minimum, maximum], −0.5% [−1.6%, 0.0%] in the ceftriaxone group and 0.0% [−5.7%, 0.2%] in the cefotaxime group) (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Box plots of the change from baseline of relative abundances (in percent) of the main bacterial phyla at day 4, day 7, day 10, day 30, and day 180 in the 22 included subjects treated with ceftriaxone (n = 11) (A) or cefotaxime (n = 11) (B). The boxes present the 25th and 75th percentiles, and the horizontal black bars report the median value, while the whiskers report the 10th and 90th percentiles.

(ii) Bacterial diversity.

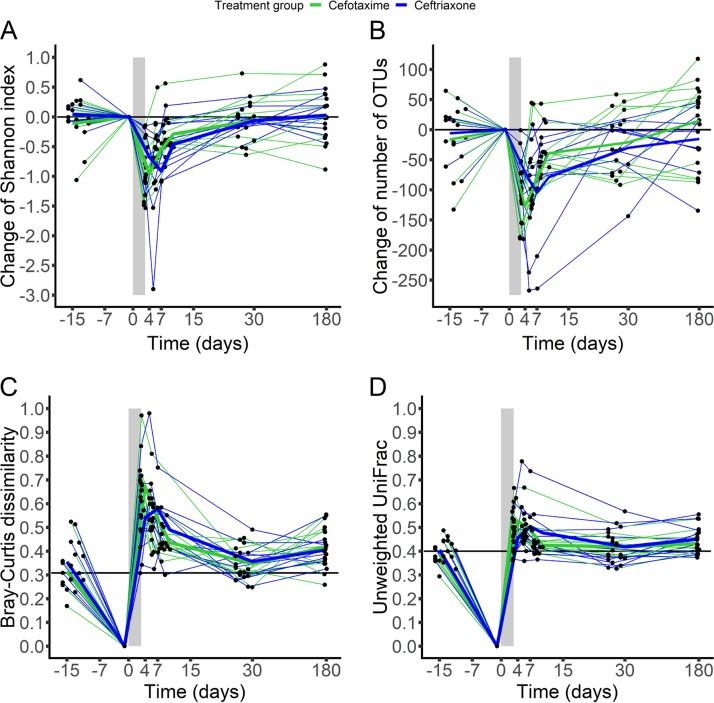

Although no significant difference was observed between ceftriaxone and cefotaxime (Table 3), both antibiotics exhibited a profound impact on bacterial diversity. The highest reduction of the Shannon index and the number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) (minimum, maximum) from baseline was 0.8 Shannon unit (0.3, 2.9 Shannon units) and 100 OTUs (40, 268 OTUs) in the ceftriaxone group and 1.1 Shannon units (0.2, 1.8 Shannon units) and 144 OTUs (97, 234 OTUs) in the cefotaxime group (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4).

FIG 3.

Evolution of the change from baseline of the Shannon index (A), change from baseline of the number of OTUs (B), Bray-Curtis dissimilarity from baseline (C), and unweighted UniFrac distance from baseline (D) in fecal samples from the 22 included subjects treated with ceftriaxone (n = 11, blue) or cefotaxime (n = 11, green). The light gray zone represents the treatment period. Thin lines represent individual values, and thick lines represent the mean of the index values at each time. In panels C and D, horizontal black lines represent the median value of the β-diversity index for each subject between samples collected at day −15 and samples collected at day −1.

At day −1, interindividual UniFrac distances appeared to be quite homogeneous, except for subject 3 (from the cefotaxime group), whose distance from the other subjects was notably higher (Fig. S5). His distance to the others increased at day 4, whereas other interindividual distances remained roughly unchanged. At day 7, subject 3 and subject 16 (from the ceftriaxone group) were very distant from the other subjects. These 2 subjects were those who exhibited detectable concentrations of antibiotics in feces. They also exhibited the highest changes of diversity over time (Fig. 3). Similar patterns were observed for the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (Fig. S6).

At day 30, the α-diversity indices returned to their baseline values, while the β-diversity indices between day −1 and day 30 were similar to the values observed between day −15 and day −1 in both groups (Fig. 3 and Fig. S7), attesting to the temporal intraindividual variability of the microbiome composition.

Pharmacokinetic endpoints were not significantly correlated with any index of bacterial diversity (Table S3).

DISCUSSION

Data from preclinical and clinical trials reported differences in ceftriaxone and cefotaxime pharmacokinetic characteristics, in particular, differences in their biliary elimination. The proportion of administered ceftriaxone excreted by bile after each dose has been estimated to be approximately 40% (13, 14), which is 4 times higher than that of cefotaxime (15, 16). In their animal study, van Ogtrop and colleagues treated mice with either cefoperazone, ceftriaxone, cefepime, or ceftazidime, whose intestinal elimination ranges from 0.2% to 37% of the administered dose (17). Although all 4 cephalosporins exhibited similar effects on Gram-negative bacteria, some differences were observed: when higher doses were administered, the impact of the antibiotics, in particular, impacts regarding colonization resistance, increased with the fractional intestinal elimination. However, differences in the antibacterial spectrum and the dosing regimens of the studied antibiotics in these animals might be responsible for some of these differences. In the CEREMI trial, we compared the impacts of two 3rd-generation cephalosporins, whose antibacterial spectrum has previously been reported to be similar, at their clinical doses to analyze specifically the impact of pharmacokinetic differences (18).

Interestingly, the fecal concentrations of both antibiotics were very low in the subjects included in the study. It was reported previously that the ceftriaxone excreted through the bile is microbiologically inactivated (19, 20). This might be due to the presence of endogenous beta-lactamases of microbial origin. Several authors reported that beta-lactam antibiotics can be inactivated by the enzymatic activity of the gut microbiota (21, 22). In particular, using a semiquantitative test for measuring the beta-lactamase activity in the fecal content, Leonard et al. observed that 2 of 6 volunteers treated by ceftriaxone exhibited undetectable levels of antibiotic when fecal beta-lactamase activity was detectable (23). This has been further illustrated by the administration of an oral beta-lactamase, which was shown to reduce the fecal concentrations of ceftriaxone (24). This beta-lactamase activity of commensal bacteria might protect against the selection of resistant Gram-negative enteric bacillus populations (25, 26).

Despite these low antibiotic concentrations, the intestinal microbiota was deeply affected by the 3-day course of both antibiotics, although no significant difference was found between the groups. It is probable that antibiotics exert their effect on the upper part of the intestine, whereas we could measure the concentrations of antibiotics only in the fecal contents. In addition, a majority of intestinal Bacteroides bacteria might not be affected by administered antibiotics and replace suppressed Gram-negative enteric bacillus populations. This would thereby leave no room for the selection of resistant Gram-negative enteric bacillus populations. To our knowledge, however, no data supporting this hypothesis are available.

The absence of a difference regarding the selection of phenotypic resistance among Gram-negative enteric bacilli might be explained by the design of the trial, which was performed in healthy volunteers. This community setting probably results in a low selective pressure, thereby limiting the risk of colonization with resistant bacterial strains. The exposure to the health care system of patients requiring intravenous antibiotic therapy might be an additional factor contributing to the differences observed in existing ecological studies (11, 12).

More startling was the similarity of both antibiotics’ impact on the microbiome. This observation might be further explained by considering the dose of each antibiotic administered. The total daily dose of cefotaxime is indeed 3 times higher than that of ceftriaxone. Using known data on biliary elimination of the 2 antibiotics, we can infer that the daily amount of antibiotic reaching the gut is roughly similar for both antibiotics (400 mg for ceftriaxone at 1 g/day and 300 mg for cefotaxime at 1 g/8 h). It is noteworthy that despite being administered at a lower daily dose, the pharmacodynamic profile of ceftriaxone, as measured by the fraction of the time during which the free plasma concentration of cefotaxime is above the susceptibility breakpoint of Enterobacteriaceae, is more favorable than that of cefotaxime, with a similar impact on the intestinal microbiota. This suggests that ceftriaxone might be better suited to reduce the overall consumption of antibiotics and thereby the environmental spread of antibiotic residues.

This work has some limitations. First, we included only healthy volunteers. Our results thus might not reflect the global effect of both antibiotics on the intestinal microbiota when treating infected patients. Here, we aimed at analyzing the intrinsic impact of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime, avoiding confounding factors, such as repeated antibiotic treatments or frequent contact with the health care system. Another limitation is the absence of data regarding beta-lactamase activity in feces. This would have provided further details on the results regarding the fecal concentrations of antibiotics. This activity might also be used as a proxy for the exposure of the intestinal microbiota to beta-lactam antibiotics. Of note, the prevalence of Gram-negative bacilli was somewhat lower than expected (27). It might have been underestimated as we chose to use a selective agar (Drigalski) in order to quantify total enterobacteria from fecal microbiota in a reproducible way, which is difficult without using selective media. Furthermore, analyses were performed on the same medium for all patients, which allowed us to avoid any differential bias.

In spite of these limitations, this trial provides further insights into the impacts of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime on the intestinal microbiota and allowed us to compare those impacts. Under our experimental conditions, our results suggest that both antibiotics exert a pronounced impact on the intestinal microbiota, extending what is already known on their antibacterial spectrum for cultivable bacteria. This was observed while the total daily dose of cefotaxime administered was 3 times higher than that of ceftriaxone, as requested in clinical practice. Deeper analysis of the resistance within the microbiota, such as the use of shotgun metagenomics for studying the fecal content of resistance-conferring genes or the use of the recently released targeted sequence capture ResCap (28), would be of great value in order to draw a complete picture of the possible difference in selective pressure between these 2 antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

We conducted a prospective, open-label, randomized clinical trial (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under identifier NCT02659033) from March 2016 to August 2017 in adult healthy volunteers in the Clinical Investigation Center at Bichat-Claude Bernard Hospital (Paris, France). All participants received oral and written information and provided signed consent before inclusion. The trial obtained approval from the Independent Ethics Committee Île-de-France 1 on 21 December 2015 (2015-oct-14028) and from the National Agency for Security of Medicinal Products on 24 July 2015 (150527A-41) and was conducted with respect to good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki as last amended. It was sponsored by Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris.

Subject selection criteria.

Male and female healthy volunteers between 18 and 65 years of age were eligible if their body mass index was between 18.5 and 30 kg/m2, if they had normal digestive transit, and if they were considered healthy by medical history, vital signs, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and blood laboratory results at a screening visit 16 to 26 days prior to randomization. Females of childbearing age were eligible if they were using contraceptives and had a negative pregnancy test at screening.

Subjects with a history of hospitalization within the previous 6 months or antibiotic exposure within the previous 3 months were not eligible, nor were those who had any history of chronic active disease, including HIV, hepatitis C virus, or hepatitis B virus infection, or a history of allergy to beta-lactams or who were under legal protection. Members of the subjects’ households could not have any active chronic disease or have received any antibiotic treatment in the preceding 15 days. The subjects were secondarily excluded if they did not provide a fecal sample before randomization or if more than 1 fecal sample was missing between day 1 and day 7 after antibiotic treatment initiation.

Treatments.

Volunteers were randomized (at a 1:1 ratio) to receive from day 1 to day 3 either ceftriaxone (1 g/24 h) or cefotaxime (1 g/8 h) as a 30-min intravenous infusion using an automatic high-precision infusion pump. Day 1 was defined as the first day of antibiotic treatment.

Plasma sampling and analyses.

For each volunteer, six blood samples were collected at day 3 for determination of the total concentration of antibiotics in plasma. In the ceftriaxone treatment group, blood samples were collected just before and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h after the beginning of the 3rd infusion. In the cefotaxime treatment group, blood samples were collected just before and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h after the 7th infusion. The exact times of the beginning and end of infusion, as well as the exact sampling times, were recorded. Blood samples were taken from the arm opposite that used for antibiotic administration.

Blood samples were immediately centrifuged (4,000 rpm for 5 min), and plasma was stored at −80°C until analysis. The total plasma concentrations of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with UV spectrophotometric detection (at 280 nm for ceftriaxone and 254 nm for cefotaxime). The limit of quantification was 0.5 mg/liter for both antibiotics.

Fecal sampling and analyses.

A total of 13 fecal samples was obtained from each participant (at days −15 ± 2, −6 ± 2, −1, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 10 ± 1, 15 ± 1, 30 ± 3, 90 ± 7, and 180 ± 7). All bacteriological analyses were performed following the PROBE guidelines (29).

(i) Determination of bacterial counts in feces.

Fecal samples were stored at 4°C after emission and transmitted to the bacteriology laboratory after they were anonymized. One hundred milligrams of feces was suspended in 1 ml of brain heart infusion broth containing 30% glycerol and stored at −80°C.

Total Gram-negative enteric bacilli (Enterobacterales) were counted by plating serial dilutions of broth on Drigalski agar (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Third-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli were detected and counted on ChromID ESBL agar (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and biplate ESBL agar (AES Chemunex, Ivry-sur-Seine, France) (37°C for 48 h). All distinct colonies were studied. Enterococcus spp. were detected and counted using Enterococcosel plates (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Intestinal colonization by Candida spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Clostridium difficile, and Staphylococcus aureus was detected, and the organisms were counted on ChromID Candida (bioMérieux), cetrimide agar (Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK), ChromID Clostridium difficile (bioMérieux), and BBL mannitol salt agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), respectively. The limit of quantification was 2.0 log10 CFU per gram of feces for all microorganisms.

Third-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacillus strains were tested for antibiotic susceptibility by the disk diffusion method described by EUCAST. The presence of an extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) was detected using the double-disk synergy test. The overproduction of intrinsic or plasmid AmpC cephalosporinase was detected by studying susceptibility on cloxacillin agar (30). Resistant strains were identified by mass spectrometry (MALDI Biotyper; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Third-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli strains were typed or sequenced by PCR (Illumina Technology) for determination of the molecular support of resistance as well as the phylogroup, sequence type, and O:H type (see Text S1 in the supplemental material).

(ii) 16S rRNA gene profiling of the intestinal microbiota.

Samples obtained at days −15 ± 2, −1, 4, 7, 10 ± 1, and 30 ± 3 were also analyzed by 16S rRNA gene profiling. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were aggregated at the phylum level, and the relative abundance of each bacterial phylum was determined. Various indices of diversity were computed. α-diversity (intrasample) metrics included the Shannon diversity index (31) and the number of observed OTUs. β-Diversity (intersample) metrics included the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity (32) and the unweighted UniFrac distance (33). Detailed methods are presented in Text S1.

(iii) Determination of fecal antibiotic concentration.

Fecal samples were stored at −80°C until the assay was performed. The fecal concentrations of active ceftriaxone and cefotaxime (and their metabolites) were measured in samples collected between day −1 and day 10 by microbiological assay (with E. coli ATCC 25922 for both antibiotics) after incubation at 37°C for 24 h, and the limit of quantification was 1.25 μg/g for both antibiotics.

Pharmacokinetic and bacteriological endpoints used for treatment comparison.

The primary endpoint was the area under the curve (AUC) between the baseline (defined as day 0) and day 7 (AUCD0D7) of the log10 counts of 3rd-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli.

Bacteriological secondary endpoints included the following: the AUC between baseline and day 15 (AUCD0D15) of the variation from baseline of the log10 counts of 3rd-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli; the AUCD0D7 and AUCD0D15 of the variation from baseline of the log10 counts of total Gram-negative enteric bacilli, Enterococcus spp., and noncommensal microorganisms in the intestinal microbiota; and the proportion of uncolonized subjects with the emergence of 3rd-generation-cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative enteric bacilli or noncommensal microorganisms in the intestinal microbiota between day 1 and day 15.

The pharmacokinetic endpoints were the area under the curve of the free plasma concentration over 24 h at steady state (fAUC0–24,ss), the maximal and trough (minimum) free plasma concentrations (fCmax and fCmin, respectively) at steady state, and the fraction of the time during which the free plasma concentration was above 1 mg/liter at steady state (fT > 1) (34).

As an exploratory analysis, we computed for each subject the AUC from day −1 to day 30 (AUCD−1D30) of the variation of the 2 indices of α-diversity. For β-diversity indices, for each sample obtained at day x, we determined the index value for each subject between day x and day −1 and computed the AUCD−1D30 of the diversity index.

Statistical methods.

The sample size of the trial was computed using data from the study by Michéa-Hamzehpour et al. (9). Assuming a common standard deviation of 2.2 log10 CFU/g of stool, the inclusion of 12 subjects in each group was required to support a 3-log10-CFU/g difference between treatment groups with a 90% power and a type I error of 0.05. Due to recruitment difficulties, inclusions were stopped on 18 April 2017. On this date, 22 volunteers (11 in each group) had been recruited. With this number, the power of the trial was estimated to be 86% using the above-described hypotheses.

We computed the variation from baseline of the bacterial and fungal counts in feces and computed the AUCs using the actual date and time of stool emission and the trapezoidal method. For each subject, the baseline value was computed as the arithmetic mean of the log10 counts observed on available pretreatment samples. The AUCD0D15 and AUCD−1D30 were normalized using the observed delay between day 0 the actual time of collection of the day 15 sample and day −1 and the actual time of collection of the day 30 sample, respectively.

The plasma concentrations of antibiotics were analyzed using the population approach (Text S1). Pharmacokinetic endpoints were derived for each antibiotic at steady state, assuming 90% protein binding for ceftriaxone (19) and 40% for cefotaxime (35). Derived pharmacokinetic endpoints (fAUC0–24,ss, fCmax, fCmin, and fT > 1) were computed for each subject using the predicted individual pharmacokinetic profiles. We used the 1-mg/liter threshold, as this value corresponds to the susceptibility breakpoint of Enterobacteriaceae species for ceftriaxone and cefotaxime (http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/).

Endpoints were compared between groups using bilateral nonparametric Wilcoxon or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, and a type I error of 0.05. We computed 95% confidence intervals of proportions using the binomial distribution. We analyzed the link between each pharmacokinetic endpoint and the AUCD−1D30 of the diversity indices studied using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient.

Data are presented as the median (minimum, maximum) or the number (percent) of subjects. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4) software (SAS Institute, USA).

Accession number(s).

Sequence data have been submitted to the EBI database under BioProject accession number PRJEB28341.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The members of the CEREMI Group include the following: for the Scientific Council, Antoine Andremont (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), Charles Burdet (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), Xavier Duval (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), Bruno Fantin (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Beaujon Hospital), Nathalie Grall (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), Estelle Marcault (Bichat Hospital), Laurent Massias (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), France Mentré (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), and Sarah Tubiana (INSERM, Bichat Hospital); for inclusion of participants and follow-up, Loubna Alavoine (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Michèle Benhayoun (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Fatima Djerdjour (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Jean-Luc Ecobichon (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Emila Ilic-Habensus (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Albane Laparra (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Milica Mandic (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Marie Ella Nisus (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Sandra Raine (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), Pascal Ralaimazava (INSERM, Bichat Hospital), and Valérie Vignali (INSERM, Bichat Hospital); for phenotypic analyses and microbiologic assays, Antoine Andremont (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), Camille d’Humières (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), Nathalie Grall (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), and Julie Riberty (Bichat Hospital); for sequencing analyses, Khadija Bourabha (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot), Antoine Bridier Nahmias (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot), Olivier Clermont (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot), Erick Denamur (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot), Mélanie Magnan (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot), and Olivier Tenaillon (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot); for plasma concentration measurements, Laurent Massias (INSERM, Univ Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital); for data management and monitoring, Estelle Marcault (Bichat Hospital), Marion Schneider (Bichat Hospital), and Isabelle Vivaldo (Bichat Hospital); and for statistical analyses, Charles Burdet (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital), Morgane Linard (Bichat Hospital), and France Mentré (INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital).

We all report no conflict of interest.

C.B., N.G., L.M, S.T., A.A., F.M., and X.D. conceived the study. C.B., E.D., A.A., F.M., and X.D. obtained funding. C.B., M.B., L.A., and X.D. included the subjects. N.G., C.D., and A.A. performed the phenotypic analyses. A.B.-N., K.B., M.M., O.T., and E.D. performed the 16S rRNA gene profiling. K.B., O.C., and E.D. performed the molecular analysis of the resistant strains. L.M. performed the pharmacologic analyses. C.B., M.L., and F.M. performed the statistical analyses. C.B., N.G., F.M., and X.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

This clinical trial was sponsored by Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (Paris, France) and funded by the Contrat de Recherche Clinique 2013 (Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Département de la Recherche Clinique et du Développement, CRC13-179). This work was partially supported by a grant from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale to E.D. (Equipe FRM 2016, grant number DEQ20161136698).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02244-18.

Contributor Information

Antoine Andremont, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Charles Burdet, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Xavier Duval, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Bruno Fantin, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Beaujon Hospital.

Nathalie Grall, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Estelle Marcault, Bichat Hospital.

Laurent Massias, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

France Mentré, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Sarah Tubiana, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Loubna Alavoine, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Michèle Benhayoun, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Fatima Djerdjour, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Jean-Luc Ecobichon, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Emila Ilic-Habensus, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Albane Laparra, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Milica Mandic, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Marie Ella Nisus, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Sandra Raine, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Pascal Ralaimazava, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Valérie Vignali, INSERM, Bichat Hospital.

Antoine Andremont, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Camille d’Humières, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Nathalie Grall, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Julie Riberty, Bichat Hospital.

Khadija Bourabha, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot.

Antoine Bridier Nahmias, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot.

Olivier Clermont, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot.

Erick Denamur, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot.

Mélanie Magnan, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot.

Olivier Tenaillon, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot.

Laurent Massias, INSERM, Univ Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Estelle Marcault, Bichat Hospital.

Marion Schneider, Bichat Hospital.

Isabelle Vivaldo, Bichat Hospital.

Charles Burdet, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Morgane Linard, Bichat Hospital.

France Mentré, INSERM, Université Paris Diderot, Bichat Hospital.

Collaborators: Antoine Andremont, Charles Burdet, Xavier Duval, Bruno Fantin, Nathalie Grall, Estelle Marcault, Laurent Massias, France Mentré, Sarah Tubiana, Loubna Alavoine, Michèle Benhayoun, Fatima Djerdjour, Jean-Luc Ecobichon, Emila Ilic-Habensus, Albane Laparra, Milica Mandic, Marie Ella Nisus, Sandra Raine, Pascal Ralaimazava, Valérie Vignali, Antoine Andremont, Camille d’Humières, Nathalie Grall, Julie Riberty, Khadija Bourabha, Antoine Bridier Nahmias, Olivier Clermont, Erick Denamur, Mélanie Magnan, Olivier Tenaillon, Laurent Massias, Estelle Marcault, Marion Schneider, Isabelle Vivaldo, Charles Burdet, Morgane Linard, and France Mentré

REFERENCES

- 1.Harper K, Armelagos G. 2010. The changing disease-scape in the third epidemiological transition. Int J Environ Res Public Health 7:675–697. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7020675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woerther PL, Burdet C, Chachaty E, Andremont A. 2013. Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clin Microbiol Rev 26:744–758. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00023-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andremont A. 2003. Commensal flora may play key role in spreading antibiotic resistance. ASM News 69:601–607. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. 2008. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol 6:e280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dethlefsen L, Relman DA. 2011. Incomplete recovery and individualized responses of the human distal gut microbiota to repeated antibiotic perturbation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(Suppl 1):4554–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Gunzburg J, Ghozlane A, Ducher A, Le Chatelier E, Duval X, Ruppé E, Armand-Lefevre L, Sablier-Gallis F, Burdet C, Alavoine L, Chachaty E, Augustin V, Varastet M, Levenez F, Kennedy S, Pons N, Mentré F, Andremont A. 2018. Protection of the human gut microbiome from antibiotics. J Infect Dis 217:628–636. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruppe E, Burdet C, Grall N, de Lastours V, Lescure FX, Andremont A, Armand LL. 2018. Impact of antibiotics on the intestinal microbiota needs to be re-defined to optimize antibiotic usage. Clin Microbiol Infect 24:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. 2012. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell 148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michéa-Hamzehpour M, Auckenthaler R, Kunz J, Pechère JC. 1988. Effect of a single dose of cefotaxime or ceftriaxone on human faecal flora. A double-blind study. Drugs 35(Suppl 2):6–11. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198800352-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brautigam HH, Knothe H, Rangoonwala R. 1988. Impact of cefotaxime and ceftriaxone on the bowel and vaginal flora after single-dose prophylaxis in vaginal hysterectomy. Drugs 35(Suppl 2):163–168. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198800352-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gbaguidi-Haore H, Dumartin C, L'Heriteau F, Pefau M, Hocquet D, Rogues AM, Bertrand X. 2013. Antibiotics involved in the occurrence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria: a nationwide multilevel study suggests differences within antibiotic classes. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:461–470. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grohs P, Kerneis S, Sabatier B, Lavollay M, Carbonnelle E, Rostane H, Souty C, Meyer G, Gutmann L, Mainardi JL. 2014. Fighting the spread of AmpC-hyperproducing Enterobacteriaceae: beneficial effect of replacing ceftriaxone with cefotaxime. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:786–789. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel IH, Chen S, Parsonnet M, Hackman MR, Brooks MA, Konikoff J, Kaplan SA. 1981. Pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone in humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 20:634–641. doi: 10.1128/AAC.20.5.634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel IH, Kaplan SA. 1984. Pharmacokinetic profile of ceftriaxone in man. Am J Med 77:17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemmerich B, Lode H, Belmega G, Jendroschek T, Borner K, Koeppe P. 1983. Comparative pharmacokinetics of cefoperazone, cefotaxime, and moxalactam. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 23:429–434. doi: 10.1128/AAC.23.3.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jehl F, Peter JD, Picard A, Dupeyron JP, Marescaux J, Sibilly A, Monteil H. 1987. Biliary excretion of cefotaxime and desacetylcefotaxime. Rev Med Interne 8:487–492. (In French) ( 10.1016/S0248-8663(87)80198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Ogtrop ML, Guiot HF, Mattie H, van Furth R. 1991. Modulation of the intestinal flora of mice by parenteral treatment with broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 35:976–982. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.5.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neu HC. 1982. The in vitro activity, human pharmacology, and clinical effectiveness of new beta-lactam antibiotics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 22:599–642. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.003123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoeckel K, McNamara PJ, Brandt R, Plozza-Nottebrock H, Ziegler WH. 1981. Effects of concentration-dependent plasma protein binding on ceftriaxone kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther 29:650–657. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakken JS, Cavalieri SJ, Gangeness D. 1990. Influence of plasma exchange pheresis on plasma elimination of ceftriaxone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 34:1276–1277. doi: 10.1128/AAC.34.6.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stiefel U, Tima MA, Nerandzic MM. 2015. Metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Bacteroides species can shield other members of the gut microbiota from antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:650–653. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03719-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stentz R, Horn N, Cross K, Salt L, Brearley C, Livermore DM, Carding SR. 2015. Cephalosporinases associated with outer membrane vesicles released by Bacteroides spp. protect gut pathogens and commensals against beta-lactam antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:701–709. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leonard F, Andremont A, Leclerq B, Labia R, Tancrede C. 1989. Use of beta-lactamase-producing anaerobes to prevent ceftriaxone from degrading intestinal resistance to colonization. J Infect Dis 160:274–280. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kokai-Kun JF, Roberts T, Coughlin O, Sicard E, Rufiange M, Fedorak R, Carter C, Adams MH, Longstreth J, Whalen H, Sliman J. 2017. The oral beta-lactamase SYN-004 (Ribaxamase) degrades ceftriaxone excreted into the intestine in phase 2a clinical studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02197-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02197-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baquero F, Tedim AP, Coque TM. 2013. Antibiotic resistance shaping multi-level population biology of bacteria. Front Microbiol 4:15. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruppé E, Ghozlane A, Tap J, Pons N, Alvarez A-S, Maziers N, Cuesta T, Hernando-Amado S, Clares I, Martínez JL, Coque TM, Baquero F, Lanza VF, Máiz L, Goulenok T, de Lastours V, Amor N, Fantin B, Wieder I, Andremont A, van Schaik W, Rogers M, Zhang X, Willems RJL, de Brevern AG, Batto J-M, Blottière HM, Léonard P, Léjard V, Letur A, Levenez F, Weiszer K, Haimet F, Doré J, Kennedy SP, Ehrlich SD. 2019. Prediction of the intestinal resistome by a three-dimensional structure-based method. Nat Microbiol 4:112–123. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenaillon O, Skurnik D, Picard B, Denamur E. 2010. The population genetics of commensal Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:207–217. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanza VF, Baquero F, Martínez JL, Ramos-Ruíz R, González-Zorn B, Andremont A, Sánchez-Valenzuela A, Ehrlich SD, Kennedy S, Ruppé E, van Schaik W, Willems RJ, de la Cruz F, Coque TM. 2018. In-depth resistome analysis by targeted metagenomics. Microbiome 6:11. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0387-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansson L, Hedner T, Dahlof B. 1992. Prospective Randomized Open Blinded End-Point (PROBE) study. A novel design for intervention trials. Blood Press 1:113–119. doi: 10.3109/08037059209077502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armand-Lefèvre L, Angebault C, Barbier F, Hamelet E, Defrance G, Ruppé E, Bronchard R, Lepeule R, Lucet J-C, El Mniai A, Wolff M, Montravers P, Plésiat P, Andremont A. 2013. Emergence of imipenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli in intestinal flora of intensive care patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:1488–1495. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01823-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shannon C. 1948. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst Tech J 27:623–656. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb00917.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bray JR, Curtis JT. 1957. An ordination of the upland forest communities of southern Wisconsin. Ecol Monogr 27:325–349. doi: 10.2307/1942268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lozupone C, Knight R. 2005. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Craig WA. 1998. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters: rationale for antibacterial dosing of mice and men. Clin Infect Dis 26:1–10. doi: 10.1086/516284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esmieu F, Guibert J, Rosenkilde HC, Ho I, Le Go A. 1980. Pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime in normal human volunteers. J Antimicrob Chemother 6(Suppl A):83–92. doi: 10.1093/jac/6.suppl_A.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.