There is a growing body of evidence for immunomodulatory side effects of antifungal agents on different immune cells, e.g., T cells. Therefore, the aim of our study was to clarify these interactions with regard to the effector functions of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN).

KEYWORDS: IL-8, antifungal agents, degranulation, neutrophil effector functions, oxidative burst, phagocytosis, polymorphonuclear leukocytes

ABSTRACT

There is a growing body of evidence for immunomodulatory side effects of antifungal agents on different immune cells, e.g., T cells. Therefore, the aim of our study was to clarify these interactions with regard to the effector functions of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN). Human PMN were preincubated with fluconazole (FLC), voriconazole (VRC), posaconazole (POS), isavuconazole (ISA), caspofungin (CAS), micafungin (MFG), conventional amphotericin B (AMB), and liposomal amphotericin B (LAMB). PMN then were analyzed by flow cytometry for activation, degranulation, and phagocytosis and by dichlorofluorescein assay to detect reactive oxygen species (ROS). Additionally, interleukin-8 (IL-8) release was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. POS led to enhanced activation, degranulation, and generation of ROS, whereas IL-8 release was reduced. In contrast, ISA-pretreated PMN showed decreased activation signaling, impaired degranulation, and lower generation of ROS. MFG caused enhanced expression of activation markers but impaired degranulation, phagocytosis, generation of ROS, and IL-8 release. CAS showed increased phagocytosis, whereas degranulation and generation of ROS were reduced. AMB led to activation of almost all effector functions besides impaired phagocytosis, whereas LAMB did not alter any effector functions. Independent from class, antifungal agents show variable influence on neutrophil effector functions in vitro. Whether this is clinically relevant needs to be clarified.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive fungal diseases (IFD) are unfortunately well-known opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients, especially after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or in patients suffering from acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (1). In these patients, molds like Aspergillus fumigatus and Mucorales spp. represent the major pathogens, followed by yeasts like Candida albicans (2). The incidence of invasive aspergillosis (IA) varies between 6% and 23% depending on the patient cohort and is associated with a high mortality of up to 60% (2–5).

To overcome this clinically highly relevant threat, patients are routinely treated with various antifungal agents in a therapeutic and prophylactic manner, especially during neutropenia (1, 6, 7). The most important antifungal substances are the orally available ergosterol synthesis-inhibiting azoles, including fluconazole (FLC), voriconazole (VRC), posaconazole (POS), and isavuconazole (ISA), the fungal cell wall synthesis-inhibiting echinocandins, e.g., micafungin (MFG) and caspofungin (CAS), and the ergosterol-interacting polyene amphotericin B in its conventional (AMB) and liposomal (LAMB) forms (8–14). In most German centers, FLC, POS, and MFG are mainly used for antifungal prophylaxis, whereas VRC, CAS, and LAMB are routinely used in antifungal therapy (6, 15). ISA is a novel member of the azole family and represents an additional promising option in anti-mold therapy (11).

Apart from antifungal medication, the antifungal immune response includes cells from the innate as well as from the adaptive immune system (16). Alongside macrophages, fungal infections are mainly fought by polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) as a major part of the innate immune response (17). Effector functions, like phagocytosis and generation of ROS, and nonoxidative mechanisms, like degranulation, are essential for executing the antipathogen response of the PMN (18, 19). Regarding fungi, PMN immune recognition is mediated via Toll-like-receptor 2 or 4 (TLR-2 or TLR-4), Dectin-1 (20–22), and other receptors, like complement receptor 3 (CR3) (23), which can be activated by lipopolysaccharides (LPS; TLR-4), zymosan (TLR-2/Dectin-1), or β-glucan (23–25). Since PMN represent the first line of defense against fungal infections, neutropenia is the primary risk factor for developing IA (17). Additionally, T cells as representatives of the adaptive immune system also contribute to the antifungal immune response. Here, type 2 (Th2) and type 17 (Th17) T-helper cells play a relevant role in coordinating and enhancing the cellular antifungal defense (26).

Despite sufficient PMN recovery shortly after HSCT, there is a relevant incidence of late fungal infections (1). This indicates an imbalance in sufficient cellular antifungal immune response partly due to side effects of the routinely administered medication. Antifungal prophylaxis, a well-established standard of care, might be one of the causatives. Further observations indicate that T cell functions are influenced by antifungal agents (27). This is supported by unpublished data from our group showing that T cell functional capabilities are suppressed in vitro and ex vivo, especially through POS, and therefore contribute to impaired immune response to IFD.

Finally, the aim of our study is to clarify the immunomodulatory capacity of different antifungal drugs on the effector functions of PMN.

RESULTS

To distinguish the impacts of antifungal drugs on PMN effector functions, we analyzed several antifungal compounds in vitro.

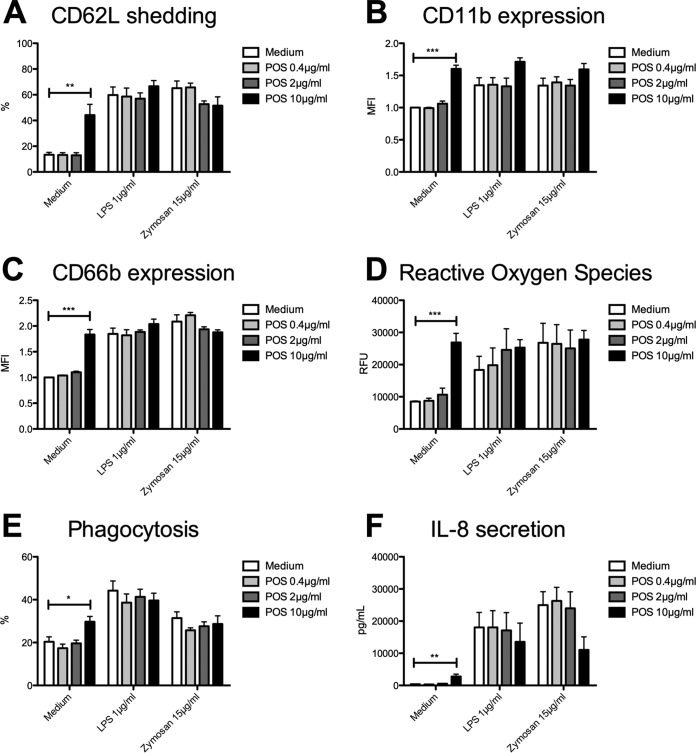

Posaconazole stimulates neutrophil effector functions.

Pretreatment with POS at 10 μg/ml resulted in upregulation of PMN activation markers, indicated by shedding of CD62L (44% ± 8% versus 13% ± 2%; values are means ± standard errors of the means [SEM]; P = 0.0026) (Fig. 1A) and CD11b upregulation (1.6% ± 0.1% versus 1.0% ± 0.0%; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1B). Neither LPS- nor zymosan-induced PMN activation was significantly affected through POS. In line with this, POS led to increased degranulation (CD66b, 1.8 ± 0.1% versus 1.0 ± 0.0%; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1C) as well as enhanced generation of ROS (26,876 ± 2,834 relative fluorescence units [RFU] versus 8,528 ± 161 RFU; P = 0.0002) (Fig. 1D). Moreover, LPS-induced generation of ROS was enhanced by trend (statistically not significant), whereas zymosan-stimulated ROS was increased to a maximum extent, indicating the higher stimulation capacity of zymosan than LPS. In addition to oxidative and nonoxidative killing mechanisms, POS also enhanced phagocytic activity compared to that of untreated controls (30% ± 2% versus 20% ± 2%; P = 0.006) (Fig. 1E). However, LPS- as well as zymosan-stimulated interleukin-8 (IL-8) production was decreased by trend (statistically not significant) after POS treatment (11,044 ± 4,083 pg/ml versus 24,994 ± 4,146 pg/ml; P = 0.1271 [zymosan]) (Fig. 1F).

FIG 1.

Posaconazole stimulates neutrophil effector functions. Isolated PMN were pretreated with POS and were analyzed for CD62L shedding (n = 3) (A), CD11b expression (n = 3) (B), CD66b expression (n = 3) (C), ROS release (n = 3) (D), phagocytosis [n (medium, zymosan) = 4, n (LPS) = 3] (E), and IL-8 release (n = 3) (F). Data are shown as means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

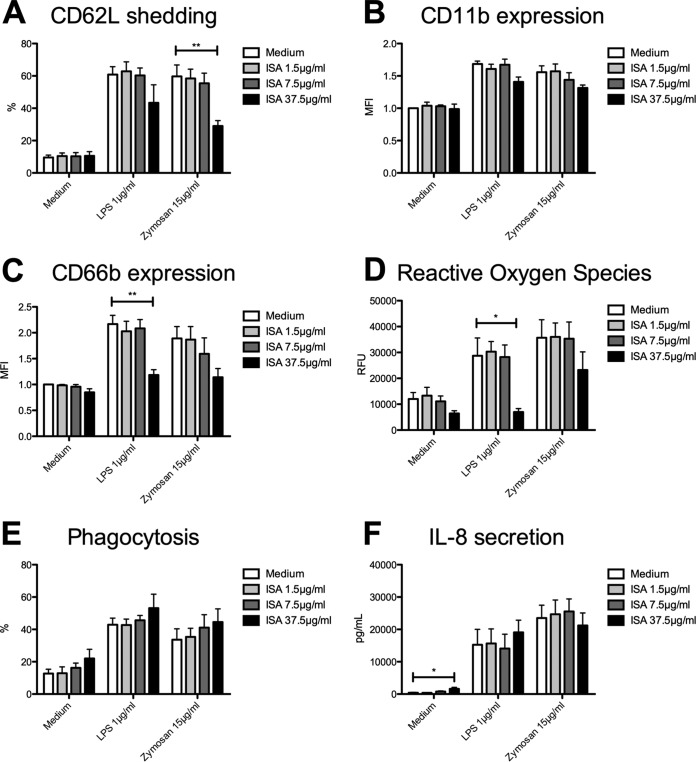

Isavuconazole impairs PMN generation of ROS.

After ISA pretreatment, PMN showed decreased expression of activation markers. In detail, LPS-induced shedding of CD62L was reduced by trend, whereas pretreatment with 37.5 μg/ml ISA led to impaired zymosan-induced CD62L shedding (29% ± 3% versus 60% ± 7%; P = 0.0082) (Fig. 2A). Likewise, CD11b expression was also decreased by trend (Fig. 2B). In line with this, pretreatment with ISA resulted in impaired LPS-triggered degranulation (1.2% ± 0.1% versus 2.2% ± 0.2%; P = 0.0034) (Fig. 2C) and lowered generation of ROS (6,980 ± 1,338 RFU versus 28,725 ± 6,893 RFU; P = 0.0222) (Fig. 2D). In fact, LPS-triggered generation of ROS was nearly totally knocked down after ISA treatment, whereas zymosan-stimulated generation of ROS was only reduced by trend. In contrast to the previously reported results after POS prestimulation, phagocytosis and production of IL-8 were not significantly affected by ISA (Fig. 2E and F).

FIG 2.

Isavuconazole impairs PMN generation of ROS. Isolated PMN were pretreated with ISA and were analyzed for CD62L shedding (n = 4) (A), CD11b expression (n = 4) (B), CD66b expression (n = 4) (C), ROS release (n = 3) (D), phagocytosis (n = 3) (E), and IL-8 release (n = 3) (F). Data are shown as means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

In contrast to POS and ISA, pretreatment with up to 250 μg/ml FLC (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and up to 62.5 μg/ml VRC (Fig. S2) did not influence neutrophil effector functions at all in vitro.

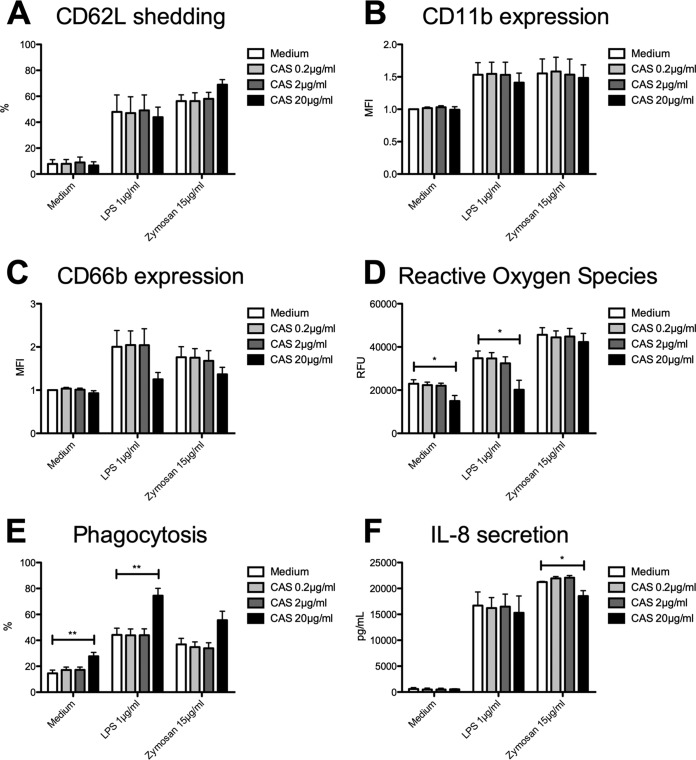

Caspofungin shows variable modifications on PMN effector functions.

Unlike that of the azoles POS and ISA, CAS pretreatment did not influence PMN expression of activation markers. Likewise, CD62L shedding (Fig. 3A) as well as CD11b upregulation (Fig. 3B) were nearly unaffected after incubation with CAS at various concentrations. However, 20 μg/ml CAS led to modification on degranulation. While CAS without additional stimulation through LPS or zymosan only slightly influenced PMN degranulation, LPS- and zymosan-triggered CD66b expression was reduced by trend after pretreatment with CAS (Fig. 3C). Similar to our findings regarding PMN activation, CAS generally had an inhibitory effect on generation of ROS. Without any costimulation, CAS led to reduced generation of ROS (14,982 ± 2,531 RFU versus 22,963 ± 1,873 RFU; P = 0.0453) (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, additional LPS stimulation also resulted in reduced generation of ROS (20,168 ± 4,391 RFU versus 34,754 ± 3,388 RFU; P = 0.0482), while incubation of the PMN with CAS and additional stimulation with zymosan did not affect their ability to generate ROS. In contrast to previously mentioned diminished effects, PMN phagocytic activity was clearly increased through CAS even in the absence of additional stimuli (28% ± 3% versus 15% ± 3%; P = 0.0134) (Fig. 3E) as well as after additional LPS stimulation (75% ± 6% versus 44% ± 5%; P = 0.0025). Here, CAS incubation in combination with zymosan also induced phagocytosis but only by trend. While CAS- and LPS-triggered IL-8 production was unaffected, zymosan-induced production of IL-8 was significantly impaired by CAS (18,527 ± 1,044 pg/ml versus 21,248 ± 107 pg/ml; P = 0.009) (Fig. 3F).

FIG 3.

Caspofungin shows variable modifications on PMN effector functions. Isolated PMN were pretreated with CAS and were analyzed for CD62L shedding (n = 4) (A), CD11b expression (n = 4) (B), CD66b expression (n = 4) (C), ROS release (n = 3) (D), phagocytosis (n = 4) (E), and IL-8 release (n = 3) (F). Data are shown as means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

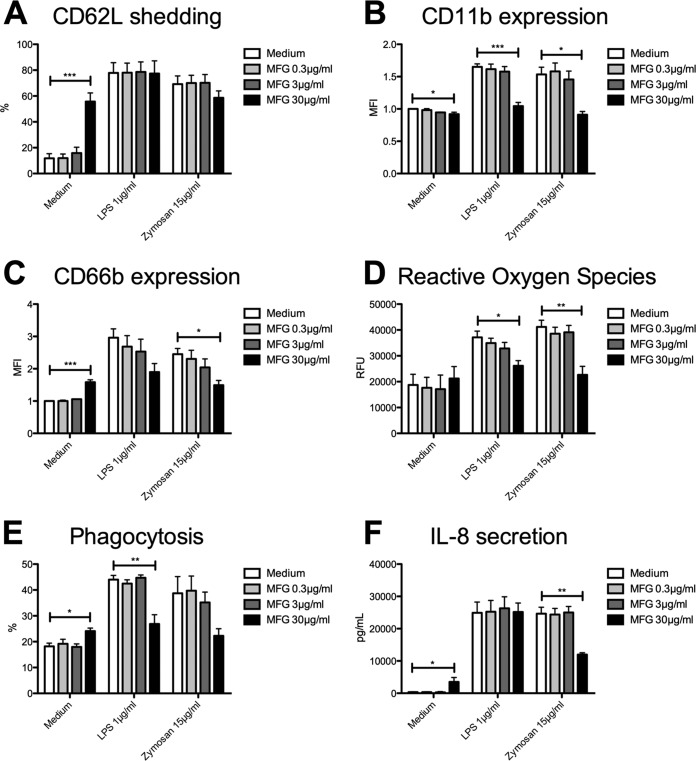

Micafungin influences PMN effector functions in different ways.

Pretreatment with 30 μg/ml MFG led to variable alteration of expression of activation markers. Incubation solely with MFG led to enhanced shedding of CD62L (55% ± 7% versus 12% ± 4%; P = 0.0004), while zymosan-induced shedding was reduced by trend and LPS-induced shedding was unaffected (Fig. 4A). Unlike CD62L shedding, CD11b expression was impaired through pretreatment with MGF alone as well as after additional LPS (1.0% ± 0.1% versus 1.7% ± 0.0%; P = 0.0006) (Fig. 4B) or zymosan (0.9% ± 0.1% versus 1.5% ± 0.1%; P = 0.009) stimulation. However, expression of CD66b was influenced in opposing directions through MFG. While sole treatment with MFG led to increased CD66b expression (1.6% ± 0.1% versus 1.0% ± 0.0%; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4C), zymosan-triggered degranulation was significantly reduced and LPS-induced degranulation was decreased by trend. Regarding generation of ROS, incubation solely with MFG did not affect ROS production (Fig. 4D), whereas additional LPS (26,134 ± 1,996 RFU versus 37,164 ± 2,411 RFU; P = 0.0338) as well as additional zymosan stimulation resulted in impaired generation of ROS (22,664 ± 3,286 RFU versus 41,194 ± 2,584 RFU; P = 0.0052). Similar to our findings regarding PMN degranulation, phagocytosis was influenced in different ways through MFG. While incubation solely with MFG resulted in increased phagocytic activity (24% ± 1% versus 18% ± 1%; P = 0.0401) (Fig. 4E), phagocytosis was impaired after LPS stimulation (27% ± 4% versus 44% ± 2%; P = 0.0012) and reduced by trend through zymosan. Concerning PMN production of IL-8, treatment solely with MFG led to enhanced IL-8 production (3,501 ± 1,378 pg/ml versus 339 ± 120 pg/ml; P = 0.0004) (Fig. 4F), while LPS-triggered IL-8 production was unaffected by MFG. In contrast, incubation with MFG caused a significant decrease in zymosan-triggered IL-8 production of approximately 50% (11,997 ± 544 pg/ml versus 24,638 ± 2,024 pg/ml; P = 0.0015).

FIG 4.

Micafungin influences PMN effector functions in different ways. Isolated PMN were pretreated with MFG and were analyzed for CD62L shedding (n = 3) (A), CD11b expression (n = 3) (B), CD66b expression (n = 3) (C), ROS release (n = 3) (D), phagocytosis (n = 3) (E), and IL-8 release (n = 3) (F). Data are shown as means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

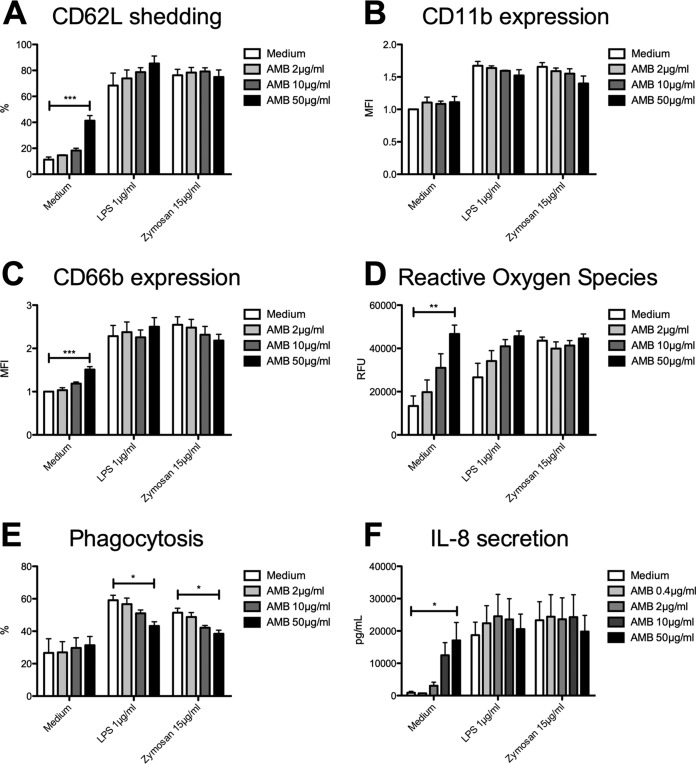

Conventional amphotericin B stimulates neutrophil effector functions, whereas liposomal amphotericin B has minor impact on PMN abilities.

Sole pretreatment with 50 μg/ml AMB resulted in enhanced shedding of CD62L (41% ± 4% versus 11% ± 2%; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5A), while LPS- and zymosan-triggered CD62L shedding was unaffected. Regarding CD11b expression, no effect by AMB was observed (Fig. 5B). In line with CD62L shedding, treatment solely with AMB at maximum concentration led to enhanced degranulation (1.5% ± 0.1% versus 1.0% ± 0.0%; P = 0.0003) (Fig. 5C) without affecting LPS- or zymosan-triggered CD66b expression. Generation of ROS was increased in a concentration-dependent manner after incubation with AMB alone (46,673 ± 4,083 RFU versus 13,396 ± 4,621 RFU; P = 0.0099) (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, LPS-triggered generation of ROS was only increased by trend through AMB, whereas zymosan-triggered generation of ROS was unaffected. In contrast to the other effector functions, LPS- and zymosan-stimulated phagocytosis was impaired after incubation with AMB (LPS, 43% ± 3% versus 59% ± 3% [P = 0.0208]; zymosan, 38% ± 2% versus 51% ± 3% [P = 0.0144]) (Fig. 5E), while incubation solely with AMB had no effect. Regarding IL-8 production, pretreatment with AMB alone stimulated cytokine production (17,094 ± 5,511 pg/ml versus 887 ± 427 pg/ml; P = 0.03) (Fig. 5F), but again LPS- or zymosan-induced production of IL-8 was unaffected.

FIG 5.

Conventional amphotericin B stimulates neutrophil effector functions. Isolated PMN were pretreated with AMB and were analyzed for CD62L shedding (n = 3) (A), CD11b expression (n = 3) (B), CD66b expression (n = 3) (C), ROS release (n = 3) (D), phagocytosis (n = 3) (E), and IL-8 release (n = 3) (F). Data are shown as means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

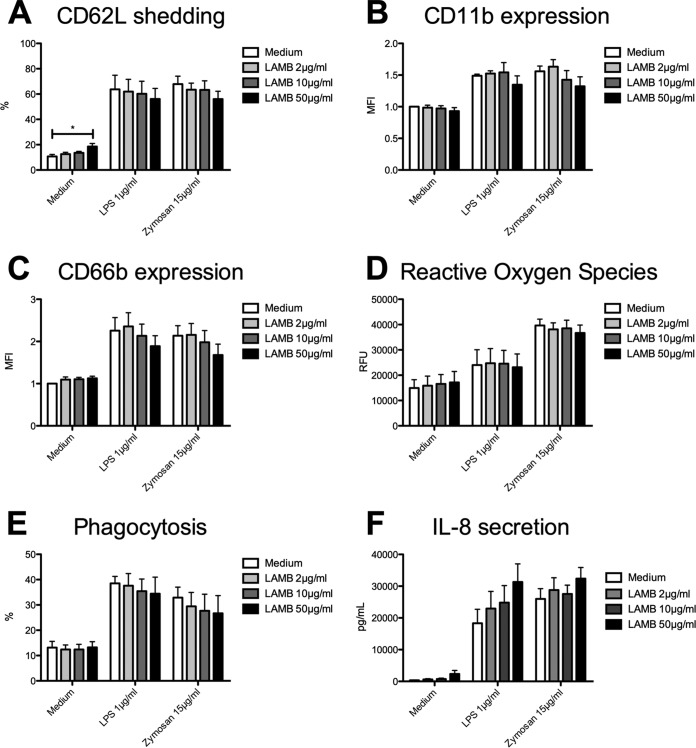

In contrast to AMB, pretreatment with 50 μg/ml LAMB resulted in only minor changes in shedding of CD62L despite being statistically significant (19% ± 2% versus 11% ± 2%; P = 0.0326) (Fig. 6A). LPS- and zymosan-induced shedding of L-selectin was not significantly affected. Furthermore, prestimulation with LAMB led to decreased LPS- as well as zymosan-induced expression of CD11b and CD66b by trend (Fig. 6B and C). However, generation of ROS as well as PMN phagocytic activity were not significantly influenced by LAMB (Fig. 6D and E). At maximum concentration, LAMB alone and also after additional LPS stimulation led to enhanced IL-8 production by trend (Fig. 6F), whereas zymosan-induced IL-8 production was nearly unaffected.

FIG 6.

Liposomal amphotericin B has no significant impact on PMN abilities. Isolated PMN were pretreated with LAMB and were analyzed for CD62L shedding [n (medium, zymosan) = 5, n (LPS) = 4] (A), CD11b expression [n (medium, zymosan) = 5, n (LPS) = 4] (B), CD66b expression [n (medium, zymosan) = 5, n (LPS) = 4] (C), ROS release (n = 4) (D), phagocytosis (n = 5) (E), and IL-8 release (n = 3) (F). Data are shown as means ± SEM. *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Critical fungal infections occur in allogeneic HSCT patients even after successful recovery of PMN (28, 29), suggesting an impaired functionality or insufficient interplay between the different parts of the immune system. These patients are routinely treated with antifungal prophylaxis for at least the first 2 to 3 months after transplantation. This presence of antifungals might be an additional contributor to impaired PMN functionality, as side effects of antifungal drugs on immune cells were previously described (30–34).

To clarify this potential interplay, we investigated PMN effector functions in the absence or presence of different antifungal compounds. To be as close as possible to the clinical setting, we decided to use dosages which reflect the common drug plasma concentrations in antifungal therapy and/or prophylaxis. Additionally, we added supratherapeutic dosages to mimic accumulation of some antifungal drugs in PMN. While we only performed a 30-min prestimulation of PMN with the antifungal compounds, we did not expect similar drug accumulation effects in vivo, as reported by others, where PMN were exposed longer to constantly high steady-state antifungal plasma levels (35).

POS was used in dosages of 0.4 and 2 μg/ml, which are close to the expected plasma concentrations of 0.8 to 2 μg/ml, especially when using POS tablets (36). Additionally, it is known that POS accumulates in PMN (35). Therefore, we think that the supratherapeutic dose of 10 μg/ml is also of clinical relevance.

For ISA, we chose 1.5 and 7.5 μg/ml. Subsequent analysis of the isavuconazole SECURE trial (37) revealed mean serum levels of 3.3 to 3.5 μg/ml, indicating at least 1.5 and 7.5 μg/ml were close to levels in the clinical setting. As ISA is expected to accumulate in PMN similarly to POS (35), we added the supratherapeutic dosage of 37.5 μg/ml to simulate this accumulation. Of note, to the best of our knowledge this assumption has not been proven so far.

The echinocandins CAS and MFG were used at concentrations of 0.2, 2, and 20 μg/ml and 0.3, 3, and 30 μg/ml, respectively. These levels corresponds to reported mean plasma concentrations of between 1 and 2 μg/ml for CAS (38) and around 3.8 μg/ml for MFG (39). The highest concentration was chosen, as levels up to 30 μg/ml MFG were reported to be accumulating in PMN (40).

For AMB and LAMB, we set the dosages to 2, 10, and 50 μg/ml, which are close to levels in the clinical setting, where plasma concentrations around 20 μg/ml are described (41, 42).

Because Sinnollareddy and others found a mean trough plasma concentration of 25 μg/ml for FLC (43), we decided to set the FLC concentrations to 10 and 50 μg/ml to be in line with the clinical setting. We also added 250 μg/ml, as higher concentrations of FLC were reported in PMN as well (44).

Regarding VRC, we assume our concentrations (2.5, 12.5, and 62.5 μg/ml) are predictive for therapeutic and prophylactic doses in patients, as Suzuki and others reported mean trough concentrations of 2 to 4 μg/ml VRC in neutropenic patients (45). Again, the higher dose was selected because of VRC accumulation of up to 8.5-fold in PMN (46).

With regard to POS, our experiments showed a PMN-activating effect along with enhanced generation of ROS and degranulation, whereas IL-8 production was decreased. Further studies done by Farowski et al. also showed effects on neutrophil effector functions in vitro (47) but found decreased generation of ROS. This difference in results might be due to the use of different assays, as Farowski et al. used the chemiluminescence assay with luminol to quantify generation of total ROS after stimulation with Aspergillus fumigatus conidia, while the dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) assay detects generation of intracellular ROS only. Second, different levels of POS might also contribute to these contrasting findings, as Farowski et al. tested POS up to 1.2 μg/ml and we decided to escalate the level to 10 μg/ml. Given that ROS produced by NADPH-oxidase is an important PMN antifungal killing mechanism (18, 48), increased ROS release might lead to improved fungal clearance, especially if POS accumulation in PMN supports this effect. As generation of ROS is also important for formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) (49), POS might enhance this relevant antifungal elimination mechanism. Apart from this possibility, the decreased production of IL-8, known as an important chemokine for PMN recruitment (50), could lead to lower numbers of PMN at the infection site, resulting in impaired pathogen clearance.

In contrast to POS, ISA resulted in impaired PMN responses in a dose-dependent manner. Interestingly, preincubation with ISA decreased PMN zymosan-induced ROS production by trend, whereas LPS-induced generation of ROS was nearly completely blocked. This indicates that ISA affects TLR-4 signaling pathways to a greater extent than TLR-2/Dectin-1 signaling, among others. In contrast to impaired degranulation and generation of ROS, the presence of ISA did not affect phagocytosis or IL-8 production, which might be due to the involvement of different signaling pathways in mediating the various effector functions. This could be also seen in the presence of CAS showing variable modifications on PMN. We previously showed that oxidative as well as nonoxidative PMN killing mechanisms are relevant to controlling A. fumigatus infections (18). Although phagocytosis is unaffected through ISA in PMN, crucial killing mechanisms are impaired. Generally, ISA is used to effectively treat mold or yeast infections (11). However, in the presence of nonfungal coinfections, e.g., by common bacterial pathogens, ISA might impair necessary immune responses mediated by PMN. Another important issue could be the impact of ISA comedication in Gram-negative bacterial sepsis; PMN are activated through recognizing LPS derived from Gram-negative bacteria via TLR-4 receptors (24), among others, which initiate a proinflammatory immune response (51). Depletion of both oxidative and nonoxidative killing mechanisms through ISA could result in impaired antibacterial cellular immune responses. In contrast, ISA could also modulate hyperinflammatory conditions, e.g., in immune reconstitution syndromes in bacterial sepsis, which are associated with increased mortality rates (51).

Other than POS and ISA, FLC and VRC did not relevantly modify neutrophil effector functions in our experiments. According to the literature, the immunomodulatory capacity of FLC is controversial; one study revealed non-cytokine-mediated increased bactericidal activity of PMN (52), while others claimed no significant immunomodulatory effects (53). Despite VRC being a commonly used antifungal drug (15), little is known about the impact of VRC on PMN beyond fungal infections. Despite increasing VRC to levels far from clinical relevance, we did not find substantial interplay between VRC and PMN effector functions in our experiments. Therefore, we assume that patients can be treated with FLC or VRC without expecting relevant immunomodulatory side effects. However, another group recently reported significantly lowered formation of NETs in the presence of VOR (49). As NETosis is dependent on NADPH-oxidase production of ROS (23), which was unaffected through VRC in our experiments, this detail might not directly result in impaired antifungal killing. Additionally, VRC was reported to collaborate with monocytes and PMN, leading to increased inhibition of hyphal growth of Aspergillus fumigatus (54) or higher candidacidal activity (55), but the underlying mechanism remained unclear.

The echinocandins are commonly seen as potent antifungal drugs with a preferable pattern of potential side effects. However, with regard to effects on PMN immune responses, we found MFG pretreatment resulted in minor induction of neutrophil effector functions, whereas stimulus-triggered effector functions were impaired. These results suggest that MFG inhibits TLR-2/Dectin-1 as well as TLR-4 signaling pathways (23, 24). Additionally, MFG simultaneously activates PMN, potentially mediated by concentration-dependent antithetic TLR signaling pathway modifications (56). However, we assume the immunomodulatory capabilities of MFG are clinically relevant, as the concentration of 30 μg/ml we used in our experiments is comparable to MFG concentrations found intracellularly in PMN (25). MFG was previously shown to influence PMN through affecting cytokine production via various signaling pathways, resulting in less inflammatory activity with improved reduction of fungal burden (31, 56).

Unlike MFG, CAS showed variable modifications on PMN effector functions. Phagocytosis was increased, whereas degranulation and generation of ROS were impaired. This is supported by previously published data showing CAS has immunomodulatory capabilities toward PMN (57). However, published data are inconsistent, showing immunostimulating as well immunosuppressive effects of CAS on PMN (33, 58).

With regard to the polyenes, treatment with conventional AMB activates nearly all PMN effector functions except phagocytosis. Here, a broad spectrum of literature is available dealing with side effects of AMB on the innate immune system (59–61). For example, it was described that AMB induces generation of ROS, leading to enhanced intracellular cell damage (62). This is caused by proinflammatory effects on PMN TLR-2 signaling pathways (63). In contrast, LAMB hardly interacts with PMN, which is mainly attributed to effects of the liposomes, which were shown to convert proinflammatory TLR signaling to noninflammatory signals (34, 64). This is in line with the generally better tolerability of LAMB than AMB. However, synergistic effects of LAMB and PMN with regard to induction of hyphal damage as measured by 2,3-bis-(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide salt (XTT) metabolic assay were described before (65), indicating an interplay at least in antifungal defense in addition to our in vitro findings. Of note, we also did not test PMN for NET formation despite recent reports of significantly lowered formation of NETs in the presence of LAMB or AMB (49). However, this could not be explained through lowered generation of ROS resulting in impaired NETosis, as we found increased (AMB) or rather unaffected ROS production (LAMB) in PMN after drug prestimulation. Additionally, our study did not analyze other signaling pathways mediated by, e.g., the β-glucan receptor CR3 (CD11b/CD18b). However, CR3 signaling is known to substantially contribute to PMN ROS production and NET formation (23) and furthermore plays a relevant role in executing PMN phagocytosis toward fungal pathogens (66).

Besides opportunistic infections, after allogeneic HSCT patients are at risk of acquiring graft-versus-host disease (GvHD), resulting in tissue damage mainly caused by CD8-positive T cells (67). Therefore, patients are routinely treated with immunosuppressive agents like cyclosporine (CsA) in the first month after transplantation. Studies from our research group showed that CsA affects neutrophil effector functions in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo (68). Therefore, in a clinical setting the immunomodulatory effects of antifungals occur concurrently with the immunogenic side effects of CsA on PMN. Furthermore, recent studies show that PMN could also be involved in generation of GvHD (69), which additionally could be modified though parallel administration of antifungal drugs.

It is well known that besides killing pathogens, ROS release causes collateral tissue damage (70). We observed that POS and conventional AMB especially resulted in enhanced generation of ROS, potentially leading to increased pulmonary tissue damage. As outlined above, this might result in a higher risk of being a trigger of acute GvHD, as alloreactive T cells are attracted by an inflammatory microenvironment. Whether these results are clinically relevant for induction of GvHD needs to be determined, as previous clinical studies mostly focused on patients with preexisting GvHD (71). However, ISA, CAS, and MFG led to a reduction of ROS production, potentially going along with less pulmonary tissue damage, and therefore might be beneficial in patients with high risk for developing a GvHD.

We showed that different antifungals cause various effects on PMN effector functions in vitro. However, it is still unclear whether our findings are of clinical relevance, and this remains the major limitation of our study. To further clarify this point, the influence of antifungals on PMN bacterial killing could be analyzed in vitro. Additionally, nonfungal infection animal models could be used to validate our findings in vivo. Here, models using Staphylococcus aureus or influenza virus are potential candidates to help us elucidate the clinical impact of antifungals on PMN anti-infective capabilities. Furthermore, ex vivo analysis of patient-derived PMN on antifungal treatment is essential to finally clarifying whether we should modify our antifungal treatment approaches with regard to unwanted immunological side effects, e.g., in patients with bacterial coinfections or with high risk for developing a GvHD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Donors.

All work involving human subjects was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Human studies with healthy volunteer blood donors were approved by the Landesaerztekammer Rhineland-Palatine Ethics Committee (approval no. 837.258.17 [11092]) according to institutional guidelines and were conducted with the understanding and informed consent of all subjects.

Isolation of human PMN.

PMN were isolated from fresh heparinized venous blood of healthy consenting volunteers by first using a dextran solution (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) to separate erythrocytes and leukocytes by sedimentation. Subsequently, PMN were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (600 × g for 30 min) using Histopaque 1077 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The pelleted cells were treated with 5 ml of cold ammonium-chloride-potassium buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for lysis of residual erythrocytes and washed two times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After centrifugation (700 × g for 5 min), pelleted cells were suspended in Iscove’s medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 3% fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma-Aldrich) and TM3 and were stored at room temperature until further use. Before starting an experiment, the PMN suspension was checked for purity (average, >95%) by flow cytometry regarding CD11b (clone M1/70; Pacific Blue [PB]; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and CD66b (clone 80H3; fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]; Beckman Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) coexpression using monoclonal antibodies.

Preparation of antifungal agents.

Prior to the in vitro experiments, the azoles POS (Sigma-Aldrich), VRC (Sigma-Aldrich), and ISA (Basilea Pharmaceutica, Basel, Switzerland) were diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich) to stock concentrations of 10 mg/ml (POS), 20 mg/ml (VRC), and 20 mg/ml (ISA). FLC (Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) and CAS (Merck Sharp & Dohme, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) were available as ready-for-infusion solutions at concentrations of 2 mg/ml (FLC) and 0.2 mg/ml (CAS). MFG (Astellas, Nihonbashi-Honcho, Tokyo, Japan) was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to a stock concentration of 10 mg/ml. AMB (reconstituted in sterile water according to the manufacturer's instructions; Sigma-Aldrich) and LAMB (Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA, USA) were concentrated to 5 mg/ml (AMB) and 4 mg/ml (LAMB) using sterile water as the dilution solvent. Prepared aliquots were stored at −80°C until use. All antifungals were prepared under sterile conditions.

Prestimulation with antifungals.

Antifungal stock solutions were diluted with TM3 to working solutions, with desired working concentrations being five times higher than the highest final concentration. Purified PMN were resuspended with antifungal working concentrations or with TM3 serving as a control at a ratio of 5:1 to reach the indicated final concentrations. Finally, PMN suspensions were placed in 96-well plates (Nunc; Thermo Fischer Scientific) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C.

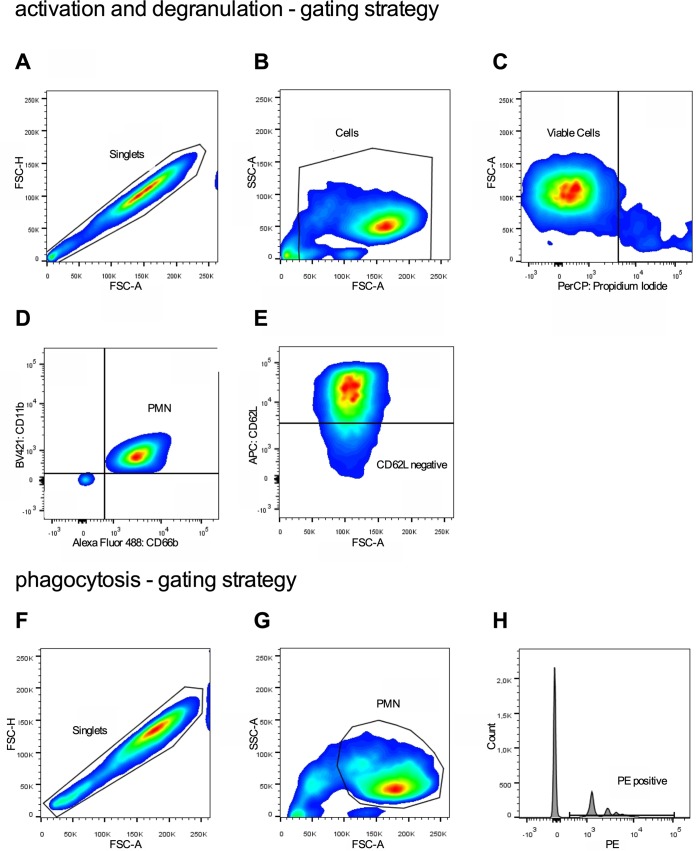

Activation and degranulation.

After preincubation with antifungals (50 μl containing 2 × 105 PMN per well), PMN were stimulated with 50 μl TM3 containing either lipopolysaccharides from Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium (final concentration of 1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) or zymosan A from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (zymosan; final concentration of 15 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), with unstimulated PMN serving as controls, for 30 min at 37°C to analyze activation and degranulation. Subsequently, PMN were washed in fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) buffer (700 × g for 3 min) and afterwards incubated with PB-labeled anti-CD11b (1:100), allophycocyanin-labeled anti-CD62L (clone DREG-56; 1:250; BioLegend), and FITC-labeled anti-CD66b monoclonal antibodies (1:400) for 20 min (4°C). Afterwards, PMN were washed twice using FACS buffer and stored at 4°C. Flow cytometric analysis was performed consecutively on a BD LSR II flow cytometer using BD FACSDIVA (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and FlowJo software, V8.8.7 (TreeStar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA). Viable leukocytes were identified by forward and side scatter (FSC and SSC) and propidium iodide (PI) staining (Sigma-Aldrich) (Fig. 7A to C). PMN were identified as CD11b and CD66b double-positive cells (Fig. 7D). Activation was quantified by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD11b-positive PMN and percentage of L-selectin (CD62L)-negative cells (Fig. 7D). Degranulation was measured by quantifying CD66b expression.

FIG 7.

Gating strategy to analyze activation, degranulation, and phagocytosis by flow cytometry. (A to C) Viable leukocytes were identified by FSC and SSC and PI staining. (D) Subsequently, PMN were characterized as CD11b and CD66b double-positive cells. (D) Activation was quantified by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD11b-positive PMN and percentage of L-selectin (CD62L)-negative cells. (F to H) Degranulation was measured by quantifying CD66b expression. Phagocytic activity was quantified by identifying the percentage of PE-positive PMN.

Phagocytosis.

To analyze phagocytic activity, PMN (50 μl containing 2 × 105 PMN per well) preincubated with antifungals were resuspended with 50 μl TM3 containing Fluoresbrite polychromatic red microspheres (final concentration of 1:100; Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA), and LPS, zymosan, or no stimuli served as the control. Subsequently, the plates were incubated for 45 min at 37°C, followed by two washes with FACS buffer (700 × g for 3 min) and storing at 4°C until final analysis. Phagocytic activity was quantified using flow cytometry by identifying the percentage of phycoerythrin (PE)-positive PMN (Fig. 7F to H).

Generation of reactive oxygen species.

In order to quantify generation of intracellular ROS, hydrogen peroxide activity was detected by oxidation of nonfluorescent DCFH-DA (8.3nM; Sigma-Aldrich) into green fluorescent DCF (72). Therefore, DCFH-DA at a final concentration of 1:14,000 and LPS, zymosan, or no stimuli were added to PMN preincubated with antifungals. Each well contained 4 × 105 PMN in a final volume of 200 μl, and triplicates were performed for better precision. Immediately, kinetics were measured with a fluorescence reader (SpectraFluor 4; Genios Crailsheim, Germany) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 520 nm as described previously (73). Finally, the quantity of intracellular ROS was indicated as mean relative fluorescence units (RFU) at 120 min.

IL-8 release.

After incubation with antifungals, PMN were stimulated in duplicate with LPS or zymosan for 24 h at 37°C. Supernatants were collected consecutively and stored at −20°C. Later, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for IL-8 (R&D Systems, Abdingdon, UK) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions to quantify IL-8 in PMN supernatant.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done with GraphPad Prism (version 5.0a for MacOS X; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Comparison of a group of results was done using one-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s posttest. For all analyses, a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the healthy volunteers for contributing to the study by donating their blood samples. M.P.R., H.S., D.T., and M.T. designed the study; A.A., F.R., H.B., P.A.L., and D.T. conducted the research; F.R., M.P.R., and D.T. carried out the data analysis; F.R. prepared the figures; F.R., M.P.R., and D.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Some of the experiments are part of the master’s thesis of F.R. This work was supported by funding of the University Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg University (TransMed and Research Center for Immunotherapy/FZI). D.T. received honoraria for lectures from Gilead, Pfizer, and MSD, is a consultant to the advisory board for Gilead, Pfizer, and MSD, and received travel support from Astellas, Gilead, and MSD. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report. We have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02409-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ullmann AJ, Schmidt-Hieber M, Bertz H, Heinz WJ, Kiehl M, Krüger W, Mousset S, Neuburger S, Neumann S, Penack O, Silling G, Vehreschild JJ, Einsele H, Maschmeyer G. 2016. Infectious diseases in allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: prevention and prophylaxis strategy guidelines 2016. Ann Hematol 95:1435–1455. doi: 10.1007/s00277-016-2711-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koehler P, Hamprecht A, Bader O, Bekeredjian-Ding I, Buchheidt D, Doelken G, Elias J, Haase G, Hahn-Ast C, Karthaus M, Kekulé A, Keller P, Kiehl M, Krause SW, Krämer C, Neumann S, Rohde H, La Rosée P, Ruhnke M, Schafhausen P, Schalk E, Schulz K, Schwartz S, Silling G, Staib P, Ullmann A, Vergoulidou M, Weber T, Cornely OA, Vehreschild MJ. 2017. Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis and azole resistance in patients with acute leukaemia: the SEPIA study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 49:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cordonnier C, Ribaud P, Herbrecht R, Milpied N, Valteau-Couanet D, Morgan C, Wade A. 2006. Prognostic factors for death due to invasive aspergillosis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a 1-year retrospective study of consecutive patients at French transplantation centers. Clin Infect Dis 42:955–963. doi: 10.1086/500934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Post MJ, Lass-Floerl C, Gastl G, Nachbaur D. 2007. Invasive fungal infections in allogeneic and autologous stem cell transplant recipients: a single-center study of 166 transplanted patients. Transpl Infect Dis 9:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2007.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H, Aljurf M, Pasquini MC, Bouzas LF, Yoshimi A, Szer J, Lipton J, Schwendener A, Gratwohl M, Frauendorfer K, Niederwieser D, Horowitz M, Kodera Y. 2010. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a global perspective. JAMA 303:1617–1624. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellinghoff SC, Panse J, Alakel N, Behre G, Buchheidt D, Christopeit M, Hasenkamp J, Kiehl M, Koldehoff M, Krause SW, Lehners N, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Löhnert AY, Maschmeyer G, Teschner D, Ullmann AJ, Penack O, Ruhnke M, Mayer K, Ostermann H, Wolf HH, Cornely OA. 2018. Primary prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in patients with haematological malignancies: 2017 update of the recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society for Haematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol 97:197–207. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3196-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinz WJ, Buchheidt D, Christopeit M, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Cornely OA, Einsele H, Karthaus M, Link H, Mahlberg R, Neumann S, Ostermann H, Penack O, Ruhnke M, Sandherr M, Schiel X, Vehreschild JJ, Weissinger F, Maschmeyer G. 2017. Diagnosis and empirical treatment of fever of unknown origin (FUO) in adult neutropenic patients: guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Medical Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol 96:1775–1792. doi: 10.1007/s00277-017-3098-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podust LM, Poulos TL, Waterman MR. 2001. Crystal structure of cytochrome P450 14alpha-sterol demethylase (CYP51) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in complex with azole inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:3068–3073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061562898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson LB, Kauffman CA. 2003. Voriconazole: a new triazole antifungal agent. Clin Infect Dis 36:630–637. doi: 10.1086/367933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore JN, Healy JR, Kraft WK. 2015. Pharmacologic and clinical evaluation of posaconazole. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 8:321–334. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.1034689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falci DR, Pasqualotto AC. 2013. Profile of isavuconazole and its potential in the treatment of severe invasive fungal infections. Infect Drug Resist 6:163–174. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S51340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deresinski SC, Stevens DA. 2003. Caspofungin. Clin Infect Dis 36:1445–1457. doi: 10.1086/375080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasmann RE, Muilwijk EW, Burger DM, Verweij PE, Knibbe CA, Brüggemann RJ. 2018. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of micafungin. Clin Pharmacokinet 57:267–286. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0578-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lestner JM, Howard SJ, Goodwin J, Gregson L, Majithiya J, Walsh TJ, Jensen GM, Hope WW. 2010. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of amphotericin B deoxycholate, liposomal amphotericin B, and amphotericin B lipid complex in an in vitro model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3432–3441. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01586-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mousset S, Buchheidt D, Heinz W, Ruhnke M, Cornely OA, Egerer G, Krüger W, Link H, Neumann S, Ostermann H, Panse J, Penack O, Rieger C, Schmidt-Hieber M, Silling G, Südhoff T, Ullmann AJ, Wolf HH, Maschmeyer G, Böhme A. 2014. Treatment of invasive fungal infections in cancer patients-updated recommendations of the Infectious Diseases Working Party (AGIHO) of the German Society of Hematology and Oncology (DGHO). Ann Hematol 93:13–32. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1867-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balloy V, Chignard M. 2009. The innate immune response to Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbes Infect 11:919–927. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garth JM, Steele C. 2017. Innate lung defense during invasive aspergillosis: new mechanisms. J Innate Immun 9:271–280. doi: 10.1159/000455125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prüfer S, Weber M, Stein P, Bosmann M, Stassen M, Kreft A, Schild H, Radsak MP. 2014. Oxidative burst and neutrophil elastase contribute to clearance of Aspergillus fumigatus pneumonia in mice. Immunobiology 219:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mambula SS, Simons ER, Hastey R, Selsted ME, Levitz SM. 2000. Human neutrophil-mediated nonoxidative antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect Immun 68:6257–6264. doi: 10.1128/IAI.68.11.6257-6264.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steele C, Rapaka RR, Metz A, Pop SM, Williams DL, Gordon S, Kolls JK, Brown GD. 2005. The beta-glucan receptor dectin-1 recognizes specific morphologies of Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Pathog 1:e42. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balloy V, Si-Tahar M, Takeuchi O, Philippe B, Nahori MA, Tanguy M, Huerre M, Akira S, Latgé JP, Chignard M. 2005. Involvement of toll-like receptor 2 in experimental invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Infect Immun 73:5420–5425. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5420-5425.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier A, Kirschning CJ, Nikolaus T, Wagner H, Heesemann J, Ebel F. 2003. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 are essential for Aspergillus-induced activation of murine macrophages. Cell Microbiol 5:561–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark HL, Abbondante S, Minns MS, Greenberg EN, Sun Y, Pearlman E. 2018. Protein deiminase 4 and CR3 regulate. Front Immunol 9:1182. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Fukudome K, Miyake K, Kimoto M. 1999. MD-2, a molecule that confers lipopolysaccharide responsiveness on Toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med 189:1777–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillon S, Agrawal S, Banerjee K, Letterio J, Denning TL, Oswald-Richter K, Kasprowicz DJ, Kellar K, Pare J, van Dyke T, Ziegler S, Unutmaz D, Pulendran B. 2006. Yeast zymosan, a stimulus for TLR2 and dectin-1, induces regulatory antigen-presenting cells and immunological tolerance. J Clin Investig 116:916–928. doi: 10.1172/JCI27203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verma A, Wüthrich M, Deepe G, Klein B. 2014. Adaptive immunity to fungi. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5:a019612. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kretschmar M, Geginat G, Bertsch T, Walter S, Hof H, Nichterlein T. 2001. Influence of liposomal amphotericin B on CD8 T-cell function. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2383–2385. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.8.2383-2385.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivasan A, Wang C, Srivastava DK, Burnette K, Shenep JL, Leung W, Hayden RT. 2013. Timeline, epidemiology, and risk factors for bacterial, fungal, and viral infections in children and adolescents after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 19:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martino R, Parody R, Fukuda T, Maertens J, Theunissen K, Ho A, Mufti GJ, Kroger N, Zander AR, Heim D, Paluszewska M, Selleslag D, Steinerova K, Ljungman P, Cesaro S, Nihtinen A, Cordonnier C, Vazquez L, López-Duarte M, Lopez J, Cabrera R, Rovira M, Neuburger S, Cornely O, Hunter AE, Marr KA, Dornbusch HJ, Einsele H. 2006. Impact of the intensity of the pretransplantation conditioning regimen in patients with prior invasive aspergillosis undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a retrospective survey of the Infectious Diseases Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood 108:2928–2936. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-008706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simitsopoulou M, Roilides E, Paliogianni F, Likartsis C, Ioannidis J, Kanellou K, Walsh TJ. 2008. Immunomodulatory effects of voriconazole on monocytes challenged with Aspergillus fumigatus: differential role of Toll-like receptors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:3301–3306. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01018-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gil-Lamaignere C, Salvenmoser S, Hess R, Müller FM. 2004. Micafungin enhances neutrophil fungicidal functions against Candida pseudohyphae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:2730–2732. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2730-2732.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuchs BB, Li Y, Li D, Johnston T, Hendricks G, Li G, Rajamuthiah R, Mylonakis E. 2016. Micafungin elicits an immunomodulatory effect in Galleria mellonella and mice. Mycopathologia 181:17–25. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9940-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tullio V, Mandras N, Scalas D, Allizond V, Banche G, Roana J, Greco D, Castagno F, Cuffini AM, Carlone NA. 2010. Synergy of caspofungin with human polymorphonuclear granulocytes for killing Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3964–3966. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01780-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellocchio S, Gaziano R, Bozza S, Rossi G, Montagnoli C, Perruccio K, Calvitti M, Pitzurra L, Romani L. 2005. Liposomal amphotericin B activates antifungal resistance with reduced toxicity by diverting Toll-like receptor signalling from TLR-2 to TLR-4. J Antimicrob Chemother 55:214–222. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farowski F, Cornely OA, Vehreschild JJ, Hartmann P, Bauer T, Steinbach A, Rüping MJ, Müller C. 2010. Intracellular concentrations of posaconazole in different compartments of peripheral blood. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:2928–2931. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01407-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tverdek FP, Heo ST, Aitken SL, Granwehr B, Kontoyiannis DP. 2017. Real-life assessment of the safety and effectiveness of the new tablet and intravenous formulations of posaconazole in the prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections via analysis of 343 courses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00188-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00188-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaindl T, Andes D, Engelhardt M, Saulay M, Larger P, Groll AH. 2019. Variability and exposure-response relationships of isavuconazole plasma concentrations in the Phase 3 SECURE trial of patients with invasive mould diseases. J Antimicrob Chemother 74:761–767. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stone JA, Holland SD, Wickersham PJ, Sterrett A, Schwartz M, Bonfiglio C, Hesney M, Winchell GA, Deutsch PJ, Greenberg H, Hunt TL, Waldman SA. 2002. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of caspofungin in healthy men. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:739–745. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.739-745.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vossen MG, Knafl D, Haidinger M, Lemmerer R, Unger M, Pferschy S, Lamm W, Maier-Salamon A, Jäger W, Thalhammer F. 2017. Micafungin plasma levels are not affected by continuous renal replacement therapy: experience in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02425-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02425-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farowski F, Cornely OA, Vehreschild JJ, Bauer T, Hartmann P, Steinbach A, Vehreschild MJ, Scheid C, Müller C. 2012. Intracellular concentrations of micafungin in different cellular compartments of the peripheral blood. Int J Antimicrob Agents 39:228–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walsh TJ, Yeldandi V, McEvoy M, Gonzalez C, Chanock S, Freifeld A, Seibel NI, Whitcomb PO, Jarosinski P, Boswell G, Bekersky I, Alak A, Buell D, Barret J, Wilson W. 1998. Safety, tolerance, and pharmacokinetics of a small unilamellar liposomal formulation of amphotericin B (AmBisome) in neutropenic patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2391–2398. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.9.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bekersky I, Fielding RM, Dressler DE, Lee JW, Buell DN, Walsh TJ. 2002. Plasma protein binding of amphotericin B and pharmacokinetics of bound versus unbound amphotericin B after administration of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (AmBisome) and amphotericin B deoxycholate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:834–840. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.834-840.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sinnollareddy MG, Roberts JA, Lipman J, Akova M, Bassetti M, De Waele JJ, Kaukonen KM, Koulenti D, Martin C, Montravers P, Rello J, Rhodes A, Starr T, Wallis SC, Dimopoulos G, DALI Study authors. 2015. Pharmacokinetic variability and exposures of fluconazole, anidulafungin, and caspofungin in intensive care unit patients: data from multinational Defining Antibiotic Levels in Intensive care unit (DALI) patients study. Crit Care 19:33. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0758-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pascual A, García I, Conejo C, Perea EJ. 1993. Uptake and intracellular activity of fluconazole in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 37:187–190. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki Y, Tokimatsu I, Sato Y, Kawasaki K, Sato Y, Goto T, Hashinaga K, Itoh H, Hiramatsu K, Kadota J-I. 2013. Association of sustained high plasma trough concentration of voriconazole with the incidence of hepatotoxicity. Clin Chim Acta 424:119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballesta S, García I, Perea EJ, Pascual A. 2005. Uptake and intracellular activity of voriconazole in human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. J Antimicrob Chemother 55:785–787. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farowski F, Cornely OA, Hartmann P. 2016. High intracellular concentrations of posaconazole do not impact on functional capacities of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils and monocyte-derived macrophages in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:3533–3539. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02060-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aratani Y, Kura F, Watanabe H, Akagawa H, Takano Y, Suzuki K, Dinauer MC, Maeda N, Koyama H. 2002. Relative contributions of myeloperoxidase and NADPH-oxidase to the early host defense against pulmonary infections with Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus. Med Mycol 40:557–563. doi: 10.1080/mmy.40.6.557.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Decker C, Wurster S, Lazariotou M, Hellmann AM, Einsele H, Ullmann AJ, Löffler J. 2018. Analysis of the in vitro activity of human neutrophils against Aspergillus fumigatus in presence of antifungal and immunosuppressive agents. Med Mycol 56:514–519. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kobayashi Y. 2008. The role of chemokines in neutrophil biology. Front Biosci 13:2400–2407. doi: 10.2741/2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Płóciennikowska A, Hromada-Judycka A, Borzęcka K, Kwiatkowska K. 2015. Co-operation of TLR4 and raft proteins in LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci 72:557–581. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1762-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zervos EE, Fink GW, Norman JG, Robson MC, Rosemurgy AS. 1996. Fluconazole increases bactericidal activity of neutrophils through non–cytokine-mediated pathway. J Trauma 41:465–470. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199609000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baldauf C, Adam D. 2000. Influence of fluconazole on phagocytosis, oxidative burst and killing activity of human phagocytes. Using a flow cytometric method with whole blood. Eur J Med Res 5:455–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vora S, Chauhan S, Brummer E, Stevens DA. 1998. Activity of voriconazole combined with neutrophils or monocytes against Aspergillus fumigatus: effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2299–2303. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.9.2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vora S, Purimetla N, Brummer E, Stevens DA. 1998. Activity of voriconazole, a new triazole, combined with neutrophils or monocytes against Candida albicans: effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:907–910. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.4.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moretti S, Bozza S, Massi-Benedetti C, Prezioso L, Rossetti E, Romani L, Aversa F, Pitzurra L. 2014. An immunomodulatory activity of micafungin in preclinical aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother 69:1065–1074. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moretti S, Bozza S, D'Angelo C, Casagrande A, Della Fazia MA, Pitzurra L, Romani L, Aversa F. 2012. Role of innate immune receptors in paradoxical caspofungin activity in vivo in preclinical aspergillosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4268–4276. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05198-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Asbeck EC, Hoepelman AI, Scharringa J, Verhoef J. 2009. The echinocandin caspofungin impairs the innate immune mechanism against Candida parapsilosis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 33:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sau K, Mambula SS, Latz E, Henneke P, Golenbock DT, Levitz SM. 2003. The antifungal drug amphotericin B promotes inflammatory cytokine release by a Toll-like receptor- and CD14-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem 278:37561–37568. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kamiński DM. 2014. Recent progress in the study of the interactions of amphotericin B with cholesterol and ergosterol in lipid environments. Eur Biophys J 43:453–467. doi: 10.1007/s00249-014-0983-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim N, Choi JW, Park HR, Kim I, Kim HS. 2017. Amphotericin B, an anti-fungal medication, directly increases the cytotoxicity of NK cells. Int J Mol Sci 18:E1262. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolf JE, Massof SE. 1990. In vivo activation of macrophage oxidative burst activity by cytokines and amphotericin B. Infect Immun 58:1296–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mesa-Arango AC, Scorzoni L, Zaragoza O. 2012. It only takes one to do many jobs: amphotericin B as antifungal and immunomodulatory drug. Front Microbiol 3:286. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lewis RE, Chamilos G, Prince RA, Kontoyiannis DP. 2007. Pretreatment with empty liposomes attenuates the immunopathology of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in corticosteroid-immunosuppressed mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:1078–1081. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01268-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simitsopoulou M, Roilides E, Maloukou A, Gil-Lamaignere C, Walsh TJ. 2008. Interaction of amphotericin B lipid formulations and triazoles with human polymorphonuclear leucocytes for antifungal activity against Zygomycetes. Mycoses 51:147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Teschner D, Cholaszczyńska A, Ries F, Beckert H, Theobald M, Grabbe S, Radsak M, Bros M. 2019. CD11b regulates fungal outgrowth but not neutrophil recruitment in a mouse model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Front Immunol 10:123. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller WP, Srinivasan S, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Singh K, Sen S, Hamby K, Deane T, Stempora L, Beus J, Turner A, Wheeler C, Anderson DC, Sharma P, Garcia A, Strobert E, Elder E, Crocker I, Crenshaw T, Penedo MC, Ward T, Song M, Horan J, Larsen CP, Blazar BR, Kean LS. 2010. GVHD after haploidentical transplantation: a novel, MHC-defined rhesus macaque model identifies CD28- CD8+ T cells as a reservoir of breakthrough T-cell proliferation during costimulation blockade and sirolimus-based immunosuppression. Blood 116:5403–5418. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Teschner D, Wenzel G, Distler E, Schnürer E, Theobald M, Neurauter AA, Schjetne K, Herr W. 2011. In vitro stimulation and expansion of human tumour-reactive CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes by anti-CD3/CD28/CD137 magnetic beads. Scand J Immunol 74:155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwab L, Goroncy L, Palaniyandi S, Gautam S, Triantafyllopoulou A, Mocsai A, Reichardt W, Karlsson FJ, Radhakrishnan SV, Hanke K, Schmitt-Graeff A, Freudenberg M, von Loewenich FD, Wolf P, Leonhardt F, Baxan N, Pfeifer D, Schmah O, Schönle A, Martin SF, Mertelsmann R, Duyster J, Finke J, Prinz M, Henneke P, Häcker H, Hildebrandt GC, Häcker G, Zeiser R. 2014. Neutrophil granulocytes recruited upon translocation of intestinal bacteria enhance graft-versus-host disease via tissue damage. Nat Med 20:648–654. doi: 10.1038/nm.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mittal M, Siddiqui MR, Tran K, Reddy SP, Malik AB. 2014. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid Redox Signal 20:1126–1167. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ullmann AJ, Lipton JH, Vesole DH, Chandrasekar P, Langston A, Tarantolo SR, Greinix H, Morais de Azevedo W, Reddy V, Boparai N, Pedicone L, Patino H, Durrant S. 2007. Posaconazole or fluconazole for prophylaxis in severe graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med 356:335–347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haselmayer P, Tenzer S, Kwon BS, Jung G, Schild H, Radsak MP. 2006. Herpes virus entry mediator synergizes with Toll-like receptor mediated neutrophil inflammatory responses. Immunology 119:404–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gladigau G, Haselmayer P, Scharrer I, Munder M, Prinz N, Lackner K, Schild H, Stein P, Radsak MP. 2012. A role for Toll-like receptor mediated signals in neutrophils in the pathogenesis of the anti-phospholipid syndrome. PLoS One 7:e42176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.