The diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is difficult and poses a significant challenge to physicians worldwide. Recently, nucleic acid amplification (NAA) tests have shown promise for the diagnosis of TBM, although their performance has been variable.

KEYWORDS: meta-analysis, test accuracy, tuberculosis, tuberculous meningitis

ABSTRACT

The diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is difficult and poses a significant challenge to physicians worldwide. Recently, nucleic acid amplification (NAA) tests have shown promise for the diagnosis of TBM, although their performance has been variable. We undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples against that of culture as the reference standard or a combined reference standard (CRS) for TBM. We searched the Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases for the relevant records. The QUADAS-2 tool was used to assess the quality of the studies. Diagnostic accuracy measures (i.e., sensitivity and specificity) were pooled with a random-effects model. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA (version 14 IC; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA), Meta-DiSc (version 1.4 for Windows; Cochrane Colloquium, Barcelona, Spain), and RevMan (version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) software. Sixty-three studies comprising 1,381 cases of confirmed TBM and 5,712 non-TBM controls were included in the final analysis. These 63 studies were divided into two groups comprising 71 data sets (43 in-house tests and 28 commercial tests) that used culture as the reference standard and 24 data sets (21 in-house tests and 3 commercial tests) that used a CRS. Studies which used a culture reference standard had better pooled summary estimates than studies which used CRS. The overall pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) of the NAA tests against culture were 82% (95% confidence interval [CI], 75 to 87%), 99% (95% CI, 98 to 99%), 58.6 (95% CI, 35.3 to 97.3), and 0.19 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.25), respectively. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR, and NLR of NAA tests against CRS were 68% (95% CI, 41 to 87%), 98% (95% CI, 95 to 99%), 36.5 (95% CI, 15.6 to 85.3), and 0.32 (95% CI, 0.15 to 0.70), respectively. The analysis has demonstrated that the diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests is currently insufficient for them to replace culture as a lone diagnostic test. NAA tests may be used in combination with culture due to the advantage of time to result and in scenarios where culture tests are not feasible. Further work to improve NAA tests would benefit from the availability of standardized reference standards and improvements to the methodology.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a global public health problem with a high mortality rate. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2017, TB caused an estimated 1.3 million deaths among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative people and an additional 300,000 deaths among HIV-positive people (1). Among all forms of TB, TB meningitis (TBM) is the most severe form, with substantial mortality (2–4). Approximately 30 to 40% of patients with TBM die despite anti-TB treatment (5, 6). Among HIV-infected patients, the rate of mortality from TBM may reach more than 60.0% (6). TBM caused by drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a mortality rate approaching 100% (7). The presenting clinical features of TBM are similar to those of other forms of subacute meningoencephalitides, making clinical diagnosis difficult and contributing to TBM’s high mortality risk due to a delay in starting treatment (8, 9). Consequently, a delay in diagnosis and the start of treatment has a negative impact on patient outcomes (8).

The cornerstones of TBM diagnosis remain the same as those for pulmonary TB: detection of acid-fast bacilli (AFB) by microscopy of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and bacterial culture (9). Although microscopy is rapid and inexpensive, it has a very low sensitivity (approximately 10 to 20%) (8, 10). Mycobacterial culture is more sensitive (60 to 70%), but the results are not available for weeks (5, 11). In many cases, confirmation of TBM cannot be made on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings, and empirical treatment is required (8). In the context of these limitations, several commercial and in-house nucleic acid amplification (NAA) techniques have emerged and are in regular use to overcome the inadequacies of conventional methods of laboratory diagnosis (12). Besides their speed to diagnosis, ability to simultaneously detect drug resistance, and ability to reduce the time to effective treatment, for areas without a laboratory infrastructure for culture or high-quality microscopy, NAA tests have great advantages over conventional methods.

In the past decade, studies on the diagnostic accuracy of molecular methods for the diagnosis of TBM have been published, but the study designs and the designs of the NAA tests have varied; thus, the exact role of these tests remains uncertain (12–19). For example, the range of genetic targets used, the capacity for on-demand testing or the need for batch testing, and the time to the final report are factors contributing to the variation of NAA test performance. Furthermore, newer tests (the lipoarabinomannan lateral flow assay, the adenosine deaminase test) are currently being evaluated as alternatives to NAA tests; hence, there is a need for better data on the diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests to allow valid comparisons (20, 21). Furthermore, the different case definitions and the different reference standard tests used in studies make comparisons of research findings difficult.

A comprehensive meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests for TBM which used microbiological diagnosis, microbiological plus clinical diagnosis, and clinical diagnosis as three different reference standards was published in 2003 (12). Newly developed commercially available tests, such as the GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay, were not available at that time (12). In 2014, a WHO systematic review of GeneXpert found a pooled sensitivity of 80.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 59.0 to 92.2%) against culture and 62.8% (95% CI, 47.7 to 75.8%) against a combined reference standard (CRS) for extrapulmonary TB (22). These findings led to a WHO recommendation for the use of GeneXpert as a first-line test for the detection of extrapulmonary TB and widespread uptake of its use worldwide (10, 23), yet other NAA tests have not been systemically investigated, and their performance compared to that of GeneXpert and the reengineered Xpert Ultra is not clear. Additionally, subsequent, substantial studies of both GeneXpert, and Xpert Ultra have been published since the WHO systematic review. Therefore, this systematic review was performed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests for TBM based on two reference standard tests: culture-confirmed TBM and a CRS.

METHODS

Search strategy.

We searched all studies published up to 11 November 2018 from the following databases: Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The following search terms were used: “Mycobacterium tuberculosis,” “tuberculosis,” “tuberculous meningitis,” “meningitis,” “cerebrospinal fluid,” “CSF,” “molecular diagnostic techniques,” “nucleic acid amplification,” “diagnosis,” “polymerase chain reaction,” “PCR,” “loop-mediated isothermal amplification,” “LAMP,” “GeneXpert,” “Xpert,” “ligase chain reaction,” “LCx,” “Amplicor,” “ProbeTec,” “Gen-Probe,” “GenoType MTBDR,” “Cobas,” “Roche,” “Abbott,” and “Cepheid.” In addition, we searched the references of the included articles to find relevant studies. Only studies written in English were selected. This study was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (24).

Study selection.

The studies found through databases that were duplicates were removed using the EndNote X7 program (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). Records were initially screened by title and abstract by two independent reviewers (A.P. and M.J.N.) to exclude those not related to the current study. The full text of potentially eligible records was retrieved and examined. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Inclusion criteria.

Studies were included if they reported a comparison of an NAA test against a reference standard and provided the data necessary for the computation of both sensitivity and specificity. We used the TBM definition according to the diagnostic index of Thwaites et al. (8) and the criteria of Marais et al. (25). Briefly, confirmed TBM was defined for any patient with a positive culture result for TBM. Likewise, CRS was defined for any patients who fulfilled the clinical criteria plus who had one or more of the following: acid-fast bacilli seen in the CSF, Mycobacterium tuberculosis cultured from CSF, or a CSF-positive NAA test. Two reviewers (A.P. and M.J.N.) independently judged study eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Exclusion criteria.

Studies were excluded if they did not report confirmed and/or suspected TBM based on the diagnostic index of Thwaites et al. (8) and the criteria of Marais et al. (25), did not report sufficient data for computation of sensitivity and specificity, and did not contain enough samples (≤10 CSF samples).

Data extraction.

The following items were extracted from each article: the first author, year of publication, study time, study location, type of NAA test used, reference standard used, number of confirmed TBM cases, number of suspected TBM cases, and number of non-TBM (control) cases. Two reviewers (A.P. and M.J.N.) independently extracted the data, and differences were resolved by consensus.

Quality assessment.

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 checklist (26).

Analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed with STATA (version 14 IC; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA), Meta-DiSc (version 1.4 for Windows; Cochrane Colloquium, Barcelona, Spain), and RevMan (version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, the Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) software. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) with 95% confidence intervals between NAA tests and the reference standard were assessed. A random-effects model was used to pool the estimated effects. Diagnostic accuracy measures (i.e., the summary receiver operating characteristic [SROC] curve and the summary positive likelihood ratios [PLR], negative likelihood ratios [NLR], and DOR) were calculated. A pooled PLR value of greater than 10 and a pooled NLR value of less than 0.1 were noted as providing convincing diagnostic evidence (27, 28). The heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using chi-square test and I-square statistics. To identify the risk of publication bias, Deek's test was used, based on parametric linear regression methods (29). Subgroup analysis was conducted using several study characteristics separately.

RESULTS

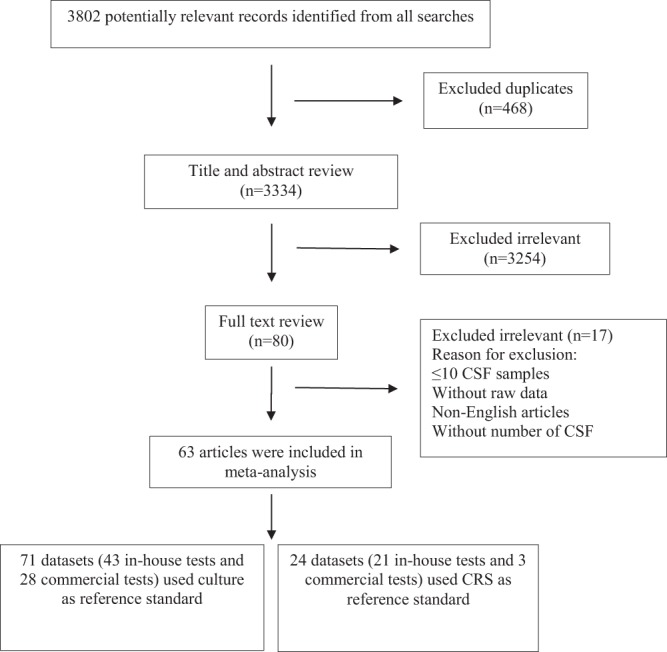

Figure 1 summarizes the study selection process. Briefly, we retrieved data from 63 selected articles comprising data for 1,381 confirmed TBM cases and 5,712 non-TBM controls. These 63 studies were divided into two groups comprising 71 data sets (43 in-house tests and 28 commercial tests) that used culture as the reference standard and 24 data sets (21 in-house tests and 3 commercial tests) that used a CRS. The characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. The studies were conducted in 22 different countries: India was the most frequently represented country (28 out of 63, 44.4%).

FIG 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of included studiesa

| First author (reference) | Country | Yr published | NAA test | Diagnostic method | Gene target(s) | Reference standard | No. of confirmed TBM cases | No. of non-TBM (control) cases | Study design | Consecutive sampling | Data collection | Blinding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dil-Afrozeb (37) | India | 2008 | In-house | Conventional PCR | MPB64 | CRS | 27 | 10 | CC | NM | R | Yes |

| Baveja (38) | India | 2009 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 22 | 78 | CS | Yes | P | NM |

| Berwal (39) | India | 2017 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 26 | 48 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| Bhigjee (40) | South Africa | 2007 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 20 | 24 | CS | NM | P | Yes |

| South Africa | 2007 | In-house | Conventional PCR | MPB64 | Culture | 20 | 24 | CS | NM | P | Yes | |

| South Africa | 2007 | In-house | Conventional PCR | Pt8/Pt9 | Culture | 20 | 24 | CS | NM | P | Yes | |

| South Africa | 2007 | In-house | Real-time PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 20 | 24 | CS | NM | P | Yes | |

| Brienze (41) | Brazil | 2001 | In-house | Nested PCR | MPB64 | CRS | 15 | 50 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| Caws (42) | United Kingdom | 2000 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 4 | 105 | CS | Yes | P | NM |

| Chaidir (43) | Indonesia | 2012 | In-house | Real-time PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 102 | 105 | CS | Yes | P | Yes |

| Desai (44) | India | 2006 | In-house | Conventional PCR (QIAamp protocol) | IS6110 | CRS | 8 | 27 | CS | Yes | P | NM |

| India | 2006 | In-house | Conventional PCR (CTAB protocol) | IS6110 | CRS | 8 | 27 | CS | Yes | P | NM | |

| Deshpande (15) | India | 2007 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 35 | 29 | CC | NM | P | NM |

| Haldar (45) | India | 2009 | In-house | Conventional PCR (filtrate protocol) | IS6110 | Culture | 10 | 86 | CS | NM | NM | Yes |

| India | 2009 | In-house | Conventional PCR (sediment protocol) | IS6110 | Culture | 10 | 86 | CS | NM | NM | Yes | |

| India | 2009 | In-house | Conventional PCR (filtrate protocol) | devR | Culture | 10 | 86 | CS | NM | NM | Yes | |

| India | 2009 | In-house | Conventional PCR (sediment protocol) | devR | Culture | 10 | 86 | CS | NM | NM | Yes | |

| India | 2009 | In-house | Real-time PCR (filtrate protocol) | devR | Culture | 10 | 86 | CS | NM | NM | Yes | |

| India | 2009 | In-house | Real-time PCR (sediment protocol) | devR | Culture | 10 | 86 | CS | NM | NM | Yes | |

| Haldar (87) | India | 2012 | In-house | Conventional PCR | devR | Culture | 29 | 338 | CS | NM | P | Yes |

| San Juan (46) | Spain | 2006 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 12 | 59 | CS | Yes | P | NM |

| Kulkarnib (18) | India | 2005 | In-house | Conventional PCR (ETBR protocol) | Protein b | CRS | 30 | 30 | CS | NM | NM | Yes |

| India | 2005 | In-house | Conventional PCR (Southern protocol) | Protein b | CRS | 30 | 30 | CS | NM | NM | Yes | |

| Lekhakb (47) | Nepal | 2016 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 37 | 75 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Nepal | 2016 | In-house | Conventional PCR | MPB64 | CRS | 37 | 75 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| Michael (48) | India | 2002 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 17 | 68 | CS | NM | R | Yes |

| Miörner (49) | India | 1995 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 6 | 34 | CC | NM | NM | NM |

| Modi (50) | India | 2016 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 50 | 100 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| India | 2016 | In-house | LAMP PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 50 | 100 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| India | 2016 | In-house | LAMP PCR | MPB64 | Culture | 50 | 100 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| Nagdev (51) | India | 2010 | In-house | Nested PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 1 | 13 | CC | NM | NM | NM |

| Nagdev (52) | India | 2010 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 13 | 139 | CC | NM | P | NM |

| Nagdevb (19) | India | 2011 | In-house | Nested PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 17 | 10 | CC | NM | R | NM |

| India | 2011 | In-house | LAMP PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 17 | 10 | CC | NM | R | NM | |

| Nagdev (53) | India | 2015 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | 16S rRNA | Culture | 8 | 85 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| India | 2015 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 8 | 85 | CS | NM | P | NM | |

| Narayanan (54) | India | 2001 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 20 | 8 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| India | 2001 | In-house | Conventional PCR | TRC4 | Culture | 20 | 8 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| Nguyen (55) | Vietnam | 1996 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 17 | 32 | CS | Yes | R | Yes |

| Palomob (56) | Brazil | 2017 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 35 | 65 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Brazil | 2017 | In-house | Conventional PCR | MBP64 | CRS | 35 | 65 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| Brazil | 2017 | In-house | Conventional PCR | hsp65 | CRS | 35 | 65 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| Portillo-Gomez (57) | Mexico | 2000 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 13 | 113 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Quan (16) | China | 2006 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 3 | 49 | CC | NM | NM | NM |

| Rafi (14) | India | 2007 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 45 | 75 | CS | NM | R | Yes |

| India | 2007 | In-house | Nested PCR | MPB64 | Culture | 45 | 75 | CS | NM | R | Yes | |

| India | 2007 | In-house | Nested PCR | 65-kDa antigen | Culture | 45 | 75 | CS | NM | R | Yes | |

| Rafi (58) | India | 2007 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 136 | 268 | CS | NM | P | Yes |

| Rana (59) | India | 2010 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 5 | 37 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| Rios-Sarabiab (60) | Mexico | 2016 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | Protein b | CRS | 50 | 50 | CC | Yes | P | Yes |

| Mexico | 2016 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | IS6110 | CRS | 50 | 50 | CC | Yes | P | Yes | |

| Mexico | 2016 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | MPB40 | CRS | 50 | 50 | CC | Yes | P | Yes | |

| Mexico | 2016 | In-house | Nested PCR | MPB40 | CRS | 50 | 50 | CC | Yes | P | Yes | |

| Sastry (61) | India | 2013 | In-house | Nested PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 2 | 33 | CC | Yes | P | NM |

| Shankar (62) | India | 1991 | In-house | Conventional PCR | MPB64 | Culture | 4 | 51 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Sharma (63) | India | 2010 | In-house | Conventional PCR | Protein b | Culture | 10 | 40 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Kusum (64) | India | 2011 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 18 | 100 | CS | Yes | NM | Yes |

| India | 2011 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | MPB64 | Culture | 18 | 100 | CS | Yes | NM | Yes | |

| India | 2011 | In-house | Multiplex PCR | Protein b | Culture | 18 | 100 | CS | Yes | NM | Yes | |

| Kusum (65) | India | 2012 | In-house | Conventional PCR | MPB64 | Culture | 9 | 40 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| Sharma (66) | India | 2015 | In-house | Real-time PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 12 | 120 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| India | 2015 | In-house | Real-time PCR | MPB64 | Culture | 12 | 120 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| India | 2015 | In-house | Real-time PCR | rpoB | Culture | 12 | 120 | CS | NM | NM | NM | |

| Sumi (67) | India | 2002 | In-house | Conventional PCR | IS6110 | Culture | 8 | 45 | CC | NM | NM | Yes |

| Bahr (10) | Uganda | 2015 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 18 | 89 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Bahr (23) | Uganda | 2018 | Commercial | GeneXpert Ultra | rpoB, IS6110, IS1081 | Culture | 22 | 107 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| Baker (68) | United States | 2002 | Commercial | Gen-Probe MTD | 16S RNA | Culture | 5 | 24 | CS | NM | NM | Yes |

| Bonington (17) | South Africa | 2000 | Commercial | Cobas Amplicor MTB | 16S RNA | Culture | 8 | 29 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| Brienze (41) | Brazil | 2001 | Commercial | Cobas Amplicor MTB | 16S RNA | CRS | 11 | 17 | CS | NM | P | NM |

| Causse (69) | Spain | 2011 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 6 | 299 | CS | Yes | NM | NM |

| Spain | 2011 | Commercial | Cobas Amplicor MTB | 16S RNA | Culture | 6 | 299 | CS | Yes | NM | NM | |

| Chedore (70) | Canada | 2002 | Commercial | Gen-Probe MTD | 16S RNA | Culture | 16 | 295 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Chua (71) | Singapore | 2005 | Commercial | Abbott LCx ligase chain reaction | Protein b | Culture | 6 | 36 | CC | NM | P | NM |

| Cox (20) | Uganda | 2015 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | CRS | 8 | 69 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Johansen (72) | Denmark | 2004 | Commercial | ProbeTec | IS6110 | Culture | 13 | 88 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Jönsson (73) | Sweden | 2003 | Commercial | Cobas Amplicor MTB | 16S RNA | Culture | 9 | 145 | CS | Yes | R | NM |

| Khan (74) | Pakistan | 2018 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 12 | 47 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Lang (88) | Dominican Republic | 1998 | Commercial | Gen-Probe MTD | 16S RNA | Culture | 5 | 60 | CS | Yes | P | NM |

| Li (75) | China | 2017 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 4 | 70 | CS | Yes | NM | NM |

| Malbruny (76) | France | 2011 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 1 | 14 | CS | Yes | P | NM |

| Moure (77) | Spain | 2012 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 2 | 12 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Nhu (13) | Vietnam | 2014 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 151 | 197 | CS | Yes | P | Yes |

| Patel (78) | South Africa | 2014 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 31 | 53 | CS | Yes | P | Yes |

| South Africa | 2014 | Commercial | Cobas Amplicor MTB | 16S RNA | Culture | 31 | 53 | CS | Yes | P | Yes | |

| Pink (79) | United Kingdom | 2016 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 37 | 703 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Rakotoarivelo (80) | Madagascar | 2018 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 13 | 31 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Rufai (81) | India | 2017 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 49 | 212 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

| Solomons (82) | South Africa | 2015 | Commercial | GenoType MTBDRplus | INH, RIF | Culture | 13 | 46 | CS | Yes | P | NM |

| South Africa | 2015 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 13 | 46 | CS | Yes | P | NM | |

| Thwaites (11) | Vietnam | 2004 | Commercial | Gen-Probe MTD | 16S RNA | Culture | 42 | 79 | CS | Yes | P | Yes |

| Tortoli (83) | Italy | 2012 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 13 | 120 | CS | NM | R | Yes |

| Vadwai (84) | India | 2011 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | CRS | 7 | 15 | CS | NM | NM | Yes |

| India | 2011 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 3 | 19 | CS | NM | NM | Yes | |

| Wang (85) | China | 2016 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 13 | 188 | CS | NM | P | Yes |

| Zmak (86) | Croatia | 2013 | Commercial | GeneXpert | rpoB | Culture | 1 | 45 | CS | NM | NM | NM |

CRS, combined reference standard; P, prospective; R, retrospective; CS, cross-sectional; CC, case-control; NM, not mentioned; CTAB, cetyltrimethylammonium bromide; ETBR, ethidium bromide; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; INH, isoniazid resistance gene; RIF, rifampin resistance gene.

These studies did not use culture to confirm TBM.

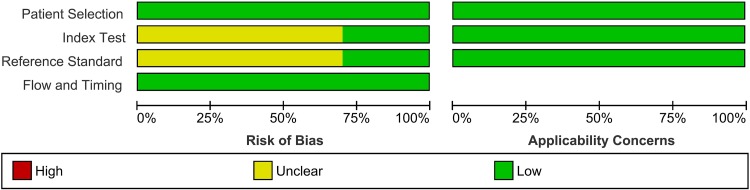

Risk of bias assessment.

Based on the results obtained with the QUADAS-2 tool, all included records were identified as having a low risk of bias, thereby increasing the strength of scientific evidence of the current study (Fig. 2). The quality assessment for each included study is provided in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

FIG 2.

QUADAS-2 assessments of the included studies. Patient Selection, describe the methods of patient selection; Index Text, describe the index test and how it was conducted and interpreted; Reference Standard, describe the reference standard (gold standard test) and how it was conducted and interpreted; Flow and Timing, describe any patients who did not receive the index tests or reference standard or who were excluded from the 2-by-2 table and describe the interval and any interventions between the index tests and the reference standard (26).

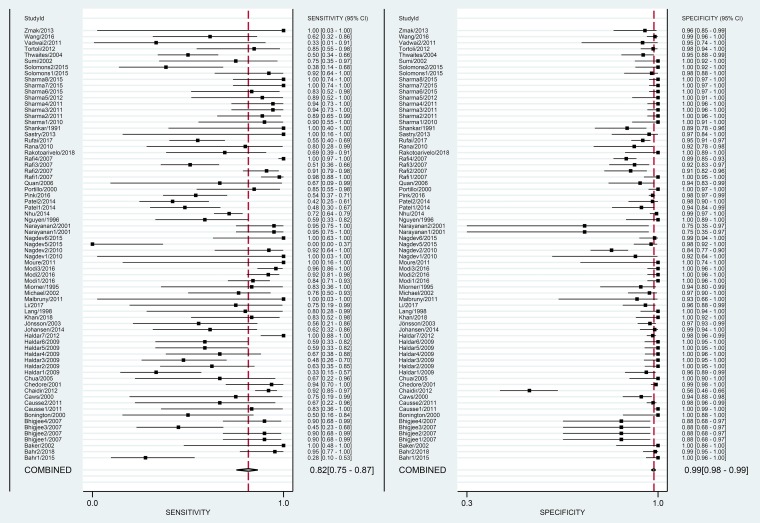

Overall diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests against culture.

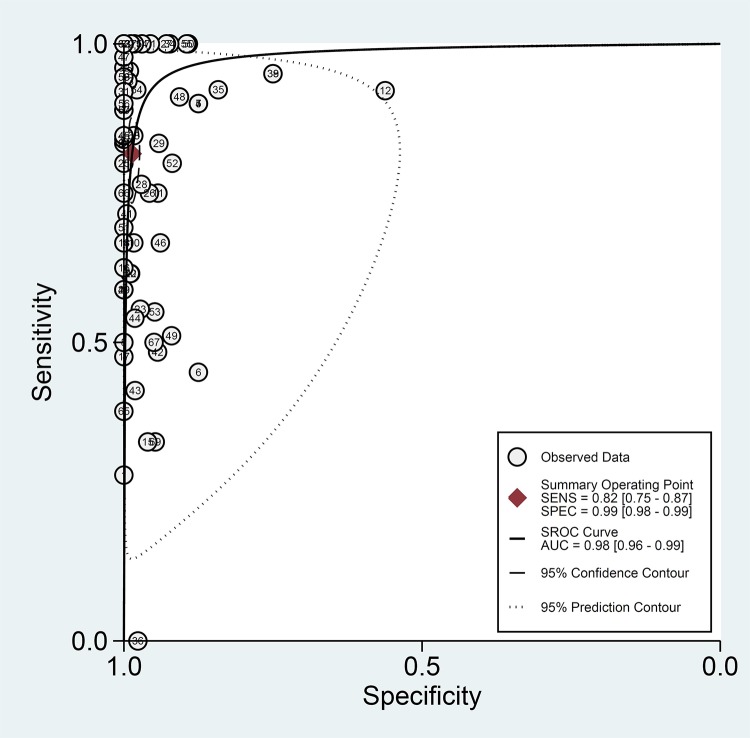

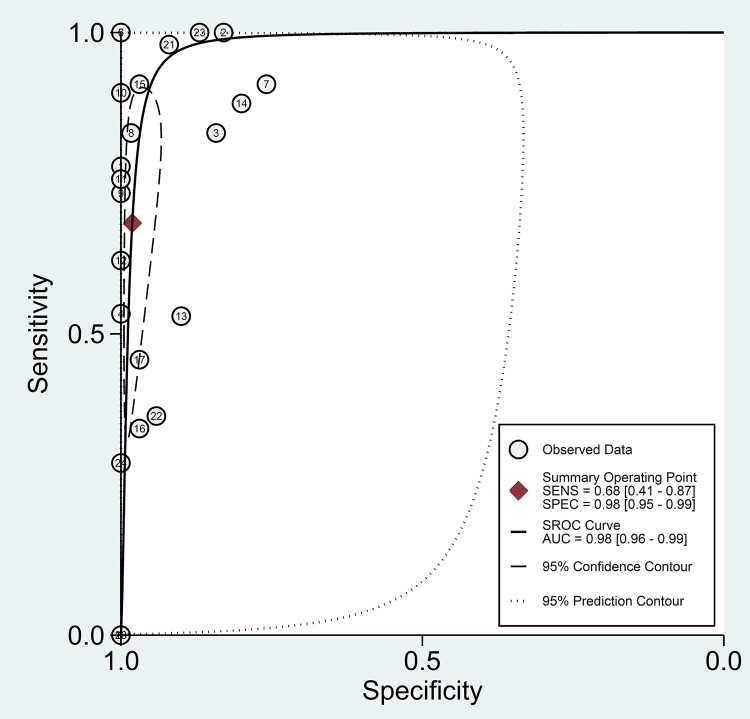

The overall pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, and DOR of NAA tests against culture were 82% (95% CI, 75 to 87%), 99% (95% CI, 98 to 99%), 58.6 (95% CI, 35.3 to 97.3%), 0.19 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.25), and 314 (169 to 584), respectively (Table 2; Fig. 3). The SROC plot showed an area under the curve (AUC) of 98% (95% CI, 96 to 99%) (Fig. 4). The result of Deek’s test indicated a low likelihood for publication bias (P = 0.01).

TABLE 2.

Summary measures of accuracy of commercial and in-house tests for all studiesa

| Reference standard | Test property | % sensitivity (95% CI, I2) | % specificity (95% CI, I2) | PLR (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All studies (63 studies) | Culture (71 data sets with 1,492 TBM cases) | 82 (75–87, 82.4) | 99 (98–99, 85.0) | 58.6 (35.3–97.3) | 0.19 (0.14–0.25) | 314 (169–584) | 98 (96–99) |

| CRS (24 data sets with 652 TBM cases) | 68 (41–87, 83.6) | 98 (95–99, 76.2) | 36.5 (15.6–85.3) | 0.32 (0.15–0.70) | 113 (39–331) | 98 (96–99) | |

| Culture (71 data sets) | In-house tests (43 data sets with 950 TBM cases) | 87 (80–92, 82.0) | 99 (97–99, 88.5) | 64.6 (28.4–147.0) | 0.13 (0.08–0.20) | 372 (165–839) | 98 (97–99) |

| Commercial tests (28 data sets with 543 TBM cases) | 67 (58–75, 64.8) | 99 (98–99, 48.3) | 46.1 (28.3–75.0) | 0.33 (0.25–0.43) | 139 (71–274) | 98 (96–99) | |

| CRS (24 data sets) | In-house tests (21 data sets with 626 TBM cases) | 68 (38–88, 83.5) | 98 (95–100, 78.0) | 44.4 (16.0–123.2) | 0.32 (0.14–0.75) | 138 (41–468) | 98 (96–99) |

| Commercial tests (3 data sets with 26 TBM cases) | 53 (33–73, 84.7) | 90 (82–95, 52.2) | 70.0 (40.0–124.2) | 0.57 (0.24–0.31) | 21 (4.2–104) | 94 (90–97) |

CRS, combined reference standard; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; AUC; area under the curve; I2, I-square statistic.

FIG 3.

Paired forest plots of pooled sensitivity and specificity of the NAA tests against culture.

FIG 4.

Summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plot for NAA tests against culture. The SROC plot shows a summary of test performance, visual assessment of the threshold effect, and the heterogeneity of the data in ROC space between sensitivity (SENS) and specificity (SPEC); each circle in the SROC plot represents a single study, and the summary operating sensitivity, specificity, and SROC curve with both confidence and prediction regions are shown. The dashed line that is around the pooled point estimate shows the 95% confidence region. The area under the curve (AUC) acts as an overall measure of test performance. In particular, when AUC is between 0.8 and 1, the accuracy is relatively high. If the SROC curve were in the upper left corner, it would show the best combination of sensitivity and specificity for the diagnostic test. The number of studies which used NAA tests against culture is shown within each circle.

Diagnostic accuracy of in-house tests against culture.

The pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates of the in-house NAA tests against culture were 87% (95% CI, 80 to 92%) and 99% (95% CI, 97 to 99%), respectively. The PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC estimates were found to be 64.6 (95% CI, 28.4 to 147.0), 0.13 (95% CI, 0.08 to 0.20), 372 (95% CI, 165 to 839), and 98% (95% CI, 97 to 99%), respectively (Table 2; Fig. S2 and S3).

Diagnostic accuracy of commercial tests against culture.

The pooled sensitivity and specificity estimates of the commercial tests against culture were 67% (95% CI, 58 to 75%) and 99% (95% CI, 98 to 99%), respectively. The PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC estimates were found to be 46.1 (95% CI, 28.3 to 75.0), 0.33 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.43), 139 (95% CI, 71 to 274), and 98% (95% CI, 96 to 99%), respectively (Table 2; Fig. S4 and S5).

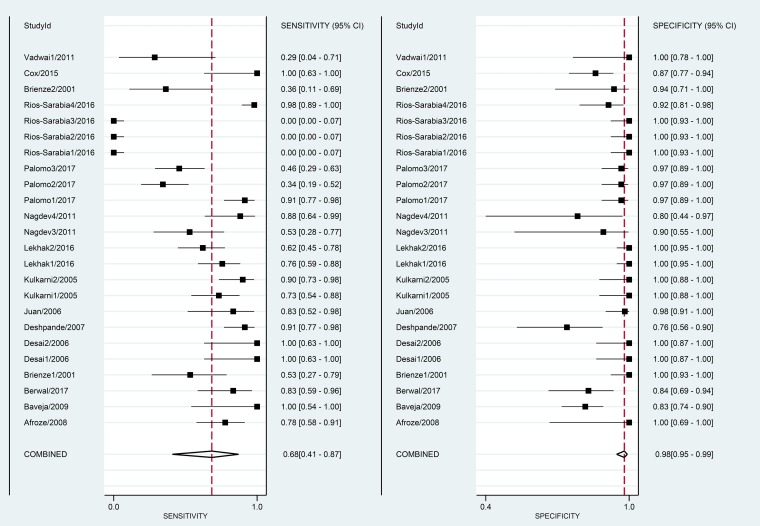

Overall diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests against CRS.

The overall pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC of NAA tests against CRS were 68% (95% CI, 41 to 87%), 98% (95% CI, 95 to 99%), 36.5 (95% CI, 15.6 to 85.3), 0.32 (95% CI, 0.15 to 0.70), 113 (95% CI, 39 to 331), and 98% (95% CI, 96 to 99%), respectively (Table 2; Fig. 5 and 6). There was no evidence of publication bias (Deek’s test P value, 0.01).

FIG 5.

Paired forest plots of pooled sensitivity and specificity of NAA tests against CRS.

FIG 6.

Summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plot for NAA tests against CRS. The number of studies which used NAA tests against CRS is shown within each circle.

Diagnostic accuracy of in-house tests against CRS.

The pooled sensitivity of in-house NAA tests against CRS was 68% (95% CI, 38 to 88%), and the pooled specificity was 98% (95% CI, 95 to 100%) (Table 2; Fig. S6 and S7). The PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC estimates were 44.4 (95% CI, 16.0 to 123.2), 0.32 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.75), 138 (95% CI, 41 to 468), and 98% (95% CI, 96 to 99%), respectively.

Diagnostic accuracy of commercial tests against CRS.

The pooled sensitivity of commercial NAA tests against CRS was 53% (33 to 73%), and the pooled specificity was 90% (95% CI, 82 to 95%). The PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC estimates were 70 (95% CI, 40.0 to 124.2), 0.57 (95% CI, 0.24 to 0.31), 21 (95% CI, 4.2 to 104), and 94% (95% CI, 90 to 97%), respectively (Table 2).

Between-group comparisons.

In the group with the culture reference standard, NAA tests revealed better pooled summary estimates (sensitivity = 82% [95% CI, 75 to 87%], specificity = 99% [95% CI, 98 to 99%], PLR = 58.6 [95% CI, 35.3 to 97.3], NLR = 0.19 [95% CI, 0.14 to 0.25], DOR = 314 [95% CI, 169 to 584], AUC = 98% [95% CI, 96 to 99%]) than the group with CRS (sensitivity = 68% [95% CI, 41 to 87%], specificity = 98% [95% CI, 95 to 99%], PLR = 36.5 [95% CI, 15.6 to 85.3], NLR = 0.32 [95% CI, 0.15 to 0.70], DOR = 113 [95% CI, 39 to 331], AUC = 98% [95% CI, 96 to 99%]) (Table 2).

In the group with the culture reference standard, the in-house tests had a higher sensitivity, PLR, and DOR than the commercial tests, a specificity and AUC comparable to those of the commercial tests, but a lower NLR than the commercial tests. Likewise, in the CRS group, the in-house tests had a higher sensitivity, specificity, and DOR than the commercial tests but a lower PLR and NLR than the commercial tests.

Subgroup analysis.

Table 3 shows the results of a subgroup analysis of the studies based on the different NAA tests.

TABLE 3.

Subgroup analysis of studies based on different NAA testsa

| Reference standard | Subgroup | Subgroup by method | No. of data sets | % sensitivity (95% CI) | % specificity (95% CI) | PLR (95% CI) | NLR (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culture | In-house | Conventional PCR (IS6110 gene) | 18 | 87 (77–93) | 98 (94–99) | 39.5 (15.7–77.1) | 0.13 (0.07–0.25) | 307 (106–888) | 98 (96–99) |

| Conventional PCR (MPB64 gene) | 4 | 92 (81–97) | 98 (78–99) | 52.0 (3.4–778.4) | 0.08 (0.03–0.20) | 275 (42–1,814) | 93 (91–95) | ||

| Nested PCR | 4 | 82 (46–96) | 92 (88–95) | 10.7 (5.9–19.4) | 0.19 (0.05–0.79) | 55 (9–339) | 93 (91–95) | ||

| Real-time PCR | 7 | 84 (71–92) | 100 (45–100) | 44.0 (5.7–335.4) | 0.16 (0.08,0.65) | 255 (40–607) | 93 (91–95) | ||

| LAMP PCR | 2 | 93 (88 –97) | 100 (98 –100) | 68.8 (0.68–925.8) | 0.07 (0.03–0.13) | ||||

| Commercial | Cobas Amplicor MTB | 4 | 48 (35–61) | 98 (97–99) | 25.3 (12.9–49.7) | 0.53 (0.41–0.68) | 48 (21–109) | 94 (91–95) | |

| GeneXpert | 16 | 61 (52–70) | 99 (97–99) | 42.0 (20.6–85.2) | 0.39 (0.31–0.50) | 107 (64–251) | 92 (89–94) | ||

| Gen-Probe MTD | 4 | 86 (52–97) | 99 (95–100) | 92.4 (14.8–577.6) | 0.15 (0.03–0.63) | 634 (31–1,299) | 99 (98–100) | ||

| CRS | In-house | Conventional PCR (IS6110 gene) | 9 | 87 (46–98) | 98 (88–100) | 39.2 (7.8–197.8) | 0.13 (0.02–0.78) | 119 (42–332) | 99 (97–99) |

| Conventional PCR (MPB64 gene) | 4 | 27 (02–85) | 99 (91–100) | 35.9 (1.7–751.1) | 0.74 (0.36–1.52) | 45 (8–249) | 99 (97–99) | ||

| Nested PCR | 3 | 80 (70 –88) | 95 (0.89–98) | 11.9 (5.3–6.7) | 0.23 (0.05–1.02) | 86 (7–1,049) | 97 (93–99) | ||

| Commercial | GeneXpert | 2 | 66 (38–88) | 89 (80–95) | 7.0 (3.8–12.8) | 0.23 (0.00–19.53) |

CRS, combined reference standard; PLR, positive likelihood ratio; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio; AUC, area under the curve; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification.

DISCUSSION

The early and accurate diagnosis of TBM is crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality. However, the different case definitions and the different reference standards used in the various studies make comparison of research findings difficult and limit the management of disease. In the present study, the sensitivity and specificity of different NAA tests were assessed based on the two most reliable reference standard tests (culture-confirmed TBM and CRS). Based on the results obtained from our analysis, we identified that the studies that used culture as a reference standard had better summary estimates than the studies that used CRS as a reference standard. Thus, the inclusion of confirmed TBM as the main reference standard test could be applied to diagnosing algorithms, which would lead to the better management of TBM.

Based on our analysis, the pooled estimates of sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC of the in-house NAA tests against culture were 87% (95% CI, 80 to 92%), 99% (95% CI, 97 to 99%), 64.6 (95% CI, 28.4 to 147.0), 0.13 (95% CI, 0.08 to 0.20), 372 (95% CI, 165 to 839), and 98% (95% CI, 96 to 99%), respectively. Likewise, the pooled sensitivity, specificity, PLR, NLR, DOR, and AUC for commercial NAA tests against culture were 67% (95% CI, 58 to 75%), 99% (95% CI, 98 to 99%), 46.1 (95% CI, 28.3 to 75.0), 0.33 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.43), 139 (95% CI, 71 to 274), and 98% (95% CI, 96 to 99%), respectively.

Although the sensitivity of the in-house tests was higher than that of the commercial NAA tests, the decontamination process, the DNA extraction protocol, the target genes adopted, the presence of PCR inhibitors, and the quality of reaction materials are among the factors that may lead to bias in the in-house tests. Thus, while these results are encouraging, in-house tests are unlikely to be a widespread answer for the accurate diagnosis of TBM.

The PLR of commercial tests was 46.1, suggesting that patients with TBM have a 46-fold higher chance of being NAA test positive than patients without TBM. In contrast to the findings from a prior systematic review performed in 2003, we found a higher sensitivity of the commercial tests (12). Furthermore, when comparing our summary estimates for commercial tests to those from the previous meta-analysis, the NLR was lower in our study (0.33 versus 0.44), but not low enough to rule out TBM with great confidence (12). Thus, our results suggest that a negative commercial NAA test result should not be used alone as a justification to rule out TBM (2). To rule out TBM, the results of NAA tests should be confirmed by conventional tests, such as culture and smear (12). In contrast, our meta-analysis indicated that a positive commercial NAA test result provides a definite diagnosis of TBM (12). Despite suboptimal sensitivity, the rapid turnaround time of commercial NAA tests compared to culture enhances their role in the early accurate diagnosis of TBM. In the management of TBM, this rapidity is of great relevance and may improve outcomes (12).

Recently, the GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay has been a major breakthrough in the diagnosis of TB meningitis (10, 13, 30). Likewise, based on the results of a systematic review published in 2014, Xpert was recommended by the WHO to be the preferred test for the diagnosis of TB meningitis (22, 31). In our analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of the GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay were 67% and 98%, respectively, against culture. By comparison, the 2014 meta-analysis by Denkinger and colleagues reported a pooled sensitivity of 80.5% against culture (22). Cost-effectiveness analysis of the use of the GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay has been completed and suggests that this technology is likely to be a highly cost-effective method of TB diagnosis; however, these analyses were not TBM specific (32–35).

More recently, Bahr et al. evaluated the diagnostic performance of the new GeneXpert MTB/RIF Ultra (Xpert Ultra) test for TBM (23). They found that Xpert Ultra had a 95% sensitivity for TBM compared to a CRS of any microbiological test being positive. When Xpert Ultra was excluded from the reference standard, sensitivity was 70%. In both analyses, Xpert Ultra’s sensitivity was higher than that of either Xpert or culture, leading the WHO to recommend Xpert Ultra as the initial test for TBM (23, 31, 36).

Some limitations of this study should be taken into consideration. First, heterogeneity exists among the included studies. To explore the heterogeneity of studies, we conducted subgroup, meta-regression, and sensitivity analyses. The subgroup and meta-regression analyses found that variables such as the NAA techniques and standard tests could be probable reasons for the heterogeneity. Second, we could not address the effect of factors such as sample volume, processing steps, amplification protocols, expertise with NAA tests, and laboratory infrastructure on the accuracy of NAA tests due to a high level of variability in these factors and/or reporting of these factors in the studies. Finally, as with any systematic review, limitations associated with potential publication bias should be considered.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis has demonstrated that the diagnostic accuracy of NAA tests is currently insufficient for them to replace culture for the diagnosis of TBM as a singular test. However, due to the more timely results from NAA tests and their ability to detect dead bacilli, the use of NAA tests in combination with culture should be considered when feasible.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is related to project NO 1396/67225 from the Student Research Committee, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. We also appreciate the Student Research Committee and Research & Technology Chancellor in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences for their financial support of this study.

A.P., N.C.B., T.D.M., and M.J.N. designed the study. A.P., M.J.N., and S.M.R. performed the literature search, collected data, and performed data analysis and data interpretation. A.P. and M.J.N. wrote the manuscript. A.P., M.J.N., N.C.B., and T.D.M. edited the manuscript.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

The Student Research Committee and the Research & Technology Chancellor of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences financially supported this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01113-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. 2018. Global tuberculosis report 2018. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahr NC, Marais S, Caws M, van Crevel R, Wilkinson RJ, Tyagi JS, Thwaites GE, Boulware DR, Aarnoutse R, Van Crevel R. 2016. GeneXpert MTB/RIF to diagnose tuberculous meningitis: perhaps the first test but not the last. Clin Infect Dis 62:1133–1135. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Török ME, Nghia HDT, Chau TTH, Mai NTH, Thwaites GE, Stepniewska K, Farrar JJ. 2007. Validation of a diagnostic algorithm for adult tuberculous meningitis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 77:555–559. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2007.77.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Well GT, Paes BF, Terwee CB, Springer P, Roord JJ, Donald PR, van Furth AM, Schoeman JF. 2009. Twenty years of pediatric tuberculous meningitis: a retrospective cohort study in the western cape of South Africa. Pediatrics 123:e1–e8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thwaites G, Chau T, Mai N, Drobniewski F, McAdam K, Farrar J. 2000. Tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 68:289–299. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Laarhoven A, Dian S, Ruesen C, Hayati E, Damen MSMA, Annisa J, Chaidir L, Ruslami R, Achmad TH, Netea MG, Alisjahbana B, Rizal Ganiem A, van Crevel R. 2017. Clinical parameters, routine inflammatory markers, and LTA4H genotype as predictors of mortality among 608 patients with tuberculous meningitis in Indonesia. J Infect Dis 215:1029–1039. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinnard C, King L, Munsiff S, Crossa A, Iwata K, Pasipanodya J, Proops D, Ahuja S. 2017. Long-term mortality of patients with tuberculous meningitis in New York City: a cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 64:401–407. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thwaites G, Chau T, Stepniewska K, Phu N, Chuong L, Sinh D, White N, Parry C, Farrar J. 2002. Diagnosis of adult tuberculous meningitis by use of clinical and laboratory features. Lancet 360:1287–1292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11318-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mai NT, Thwaites GE. 2017. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of tuberculous meningitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 30:123–128. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bahr NC, Tugume L, Rajasingham R, Kiggundu R, Williams DA, Morawski B, Alland D, Meya DB, Rhein J, Boulware DR. 2015. Improved diagnostic sensitivity for tuberculous meningitis with Xpert MTB/RIF of centrifuged CSF. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 19:1209–1215. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thwaites GE, Caws M, Chau TTH, Dung NT, Campbell JI, Phu NH, Hien TT, White NJ, Farrar JJ. 2004. Comparison of conventional bacteriology with nucleic acid amplification (amplified Mycobacterium direct test) for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis before and after inception of antituberculosis chemotherapy. J Clin Microbiol 42:996–1002. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.996-1002.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pai M, Flores LL, Pai N, Hubbard A, Riley LW, Colford JM. 2003. Diagnostic accuracy of nucleic acid amplification tests for tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 3:633–643. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nhu NTQ, Heemskerk D, Thu DDA, Chau TTH, Mai NTH, Nghia HDT, Loc PP, Ha DTM, Merson L, Thinh TTV, Day J, Chau NVV, Wolbers M, Farrar J, Caws M. 2014. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 52:226–233. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01834-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rafi W, Venkataswamy MM, Ravi V, Chandramuki A. 2007. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: a comparative evaluation of in-house PCR assays involving three mycobacterial DNA sequences, IS6110, MPB-64 and 65 kDa antigen. J Neurol Sci 252:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deshpande PS, Kashyap RS, Ramteke SS, Nagdev KJ, Purohit HJ, Taori GM, Daginawala HF. 2007. Evaluation of the IS6110 PCR assay for the rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 4:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan C, Lu C-Z, Qiao J, Xiao B-G, Li X. 2006. Comparative evaluation of early diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis by different assays. J Clin Microbiol 44:3160–3166. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00333-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonington A, Strang JI, Klapper PE, Hood SV, Parish A, Swift PJ, Damba J, Stevens H, Sawyer L, Potgieter G, Bailey A, Wilkins EG. 2000. TB PCR in the early diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: evaluation of the Roche semi-automated COBAS Amplicor MTB test with reference to the manual Amplicor MTB PCR test. Tuberc Lung Dis 80:191–196. doi: 10.1054/tuld.2000.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kulkarni S, Jaleel M, Kadival G. 2005. Evaluation of an in-house-developed PCR for the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in Indian children. J Med Microbiol 54:369–373. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45801-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagdev KJ, Kashyap RS, Parida MM, Kapgate RC, Purohit HJ, Taori GM, Daginawala HF. 2011. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid and reliable diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 49:1861–1865. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00824-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cox JA, Lukande RL, Kalungi S, Van Marck E, Lammens M, Van de Vijver K, Kambugu A, Nelson AM, Colebunders R, Manabe YC. 2015. Accuracy of lipoarabinomannan and Xpert MTB/RIF testing in cerebrospinal fluid to diagnose TB meningitis in an autopsy cohort of HIV-infected adults. J Clin Microbiol 53:e00624-15. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00624-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sivakumar P, Marples L, Breen R, Ahmed L. 2017. The diagnostic utility of pleural fluid adenosine deaminase for tuberculosis in a low prevalence area. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 21:697–701. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denkinger CM, Schumacher SG, Boehme CC, Dendukuri N, Pai M, Steingart KR. 2014. Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 44:435–446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00007814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahr NC, Nuwagira E, Evans EE, Cresswell FV, Bystrom PV, Byamukama A, Bridge SC, Bangdiwala AS, Meya DB, Denkinger CM, Muzoora C, Boulware DR. 2018. Diagnostic accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for tuberculous meningitis in HIV-infected adults: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 18:68–75. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30474-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marais S, Thwaites G, Schoeman JF, Török ME, Misra UK, Prasad K, Donald PR, Wilkinson RJ, Marais BJ. 2010. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis 10:803–812. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM. 2011. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mengoli C, Cruciani M, Barnes RA, Loeffler J, Donnelly JP. 2009. Use of PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu Y, Chen Y-Q, Guo Y-L, Qin S-M, Wu C, Wang K. 2011. Diagnosis of invasive fungal disease using serum (1→3)-β-d-glucan: a bivariate meta-analysis. Intern Med 50:2783–2791. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.6175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Enst WA, Ochodo E, Scholten RJ, Hooft L, Leeflang MM. 2014. Investigation of publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel VB, Theron G, Lenders L, Matinyena B, Connolly C, Singh R, Coovadia Y, Ndung'u T, Dheda K. 2013. Diagnostic accuracy of quantitative PCR (Xpert MTB/RIF) for tuberculous meningitis in a high burden setting: a prospective study. PLoS Med 10:e1001536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. 2013. Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MT. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawn SD, Mwaba P, Bates M, Piatek A, Alexander H, Marais BJ, Cuevas LE, McHugh TD, Zijenah L, Kapata N, Abubakar I, McNerney R, Hoelscher M, Memish ZA, Migliori GB, Kim P, Maeurer M, Schito M, Zumla A. 2013. Advances in tuberculosis diagnostics: the Xpert MTB/RIF assay and future prospects for a point-of-care test. Lancet Infect Dis 13:349–361. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70008-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vassall A, van Kampen S, Sohn H, Michael JS, John KR, den Boon S, Davis JL, Whitelaw A, Nicol MP, Gler MT, Khaliqov A, Zamudio C, Perkins MD, Boehme CC, Cobelens F. 2011. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis with the Xpert MTB/RIF assay in high burden countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis. PLoS Med 8:e1001120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews JR, Lawn SD, Rusu C, Wood R, Noubary F, Bender MA, Horsburgh CR, Losina E, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. 2012. The cost-effectiveness of routine tuberculosis screening with Xpert MTB/RIF prior to initiation of antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a model-based analysis. AIDS 26:987. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522d47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meyer-Rath G, Schnippel K, Long L, MacLeod W, Sanne I, Stevens W, Pillay S, Pillay Y, Rosen S. 2012. The impact and cost of scaling up GeneXpert MTB/RIF in South Africa. PLoS One 7:e36966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization. 2017. WHO meeting report of a technical expert consultation: non-inferiority analysis of Xpert MT. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dil-Afroze AW, Mir AW, Kirmani A, Eachkoti R, Siddiqi MA. 2008. Improved diagnosis of central nervous system tuberculosis by MPB64-target PCR. Braz J Microbiol 39:209–213. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822008000200002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baveja C, Gumma V, Manisha J, Choudhary M, Talukdar B, Sharma V. 2009. Newer methods over the conventional diagnostic tests for tuberculous meningitis: do they really help? Trop Doct 39:18–20. doi: 10.1258/td.2008.080082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berwal A, Chawla K, Vishwanath S, Shenoy VP. 2017. Role of multiplex polymerase chain reaction in diagnosing tubercular meningitis. J Lab Physicians 9:145. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.199633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhigjee AI, Padayachee R, Paruk H, Hallwirth-Pillay KD, Marais S, Connoly C. 2007. Diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: clinical and laboratory parameters. Int J Infect Dis 11:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brienze VMS, Tonon ÂP, Pereira FJT, Liso E, Tognola WA, Santos M, Ferreira MU. 2001. Low sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in southeastern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 34:389–393. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822001000400015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caws M, Wilson SM, Clough C, Drobniewski F. 2000. Role of IS6110-targeted PCR, culture, biochemical, clinical, and immunological criteria for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 38:3150–3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaidir L, Ganiem AR, Vander Zanden A, Muhsinin S, Kusumaningrum T, Kusumadewi I, van der Ven A, Alisjahbana B, Parwati I, van Crevel R. 2012. Comparison of real time IS6110-PCR, microscopy, and culture for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in a cohort of adult patients in Indonesia. PLoS One 7:e52001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Desai D, Nataraj G, Kulkarni S, Bichile L, Mehta P, Baveja S, Rajan R, Raut A, Shenoy A. 2006. Utility of the polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Res Microbiol 157:967–970. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haldar S, Sharma N, Gupta V, Tyagi JS. 2009. Efficient diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis by detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in cerebrospinal fluid filtrates using PCR. J Med Microbiol 58:616–624. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.006015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.San Juan R, Sánchez-Suárez C, Rebollo MJ, Folgueira D, Palenque E, Ortuño B, Lumbreras C, Aguado JM. 2006. Interferon γ quantification in cerebrospinal fluid compared with PCR for the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol 253:1323–1330. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lekhak SP, Sharma L, Rajbhandari R, Rajbhandari P, Shrestha R, Pant B. 2016. Evaluation of multiplex PCR using MPB64 and IS6110 primers for rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 100:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michael JS, Lalitha M, Cherian T, Thomas K, Mathai D, Abraham O, Brahmadathan K. 2002. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction for rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Indian J Tuberc 49:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miörner H, Sjöbring U, Nayak P, Chandramuki A. 1995. Diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: a comparative analysis of 3 immunoassays, an immune complex assay and the polymerase chain reaction. Tuber Lung Dis 76:381–386. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Modi M, Sharma K, Sharma M, Sharma A, Sharma N, Sharma S, Ray P, Varma S. 2016. Multitargeted loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 20:625–630. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagdev KJ, Kashyap RS, Deshpande PS, Purohit HJ, Taori GM, Daginawala HF. 2010. Determination of polymerase chain reaction efficiency for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in Chelex-100 extracted DNA samples. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 14:1032–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagdev KJ, Kashyap RS, Deshpande PS, Purohit HJ, Taori GM, Daginawala HF. 2010. Comparative evaluation of a PCR assay with an in-house ELISA method for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 16:CR289–CR295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nagdev KJ, Bhagchandani SP, Bhullar SS, Kapgate RC, Kashyap RS, Chandak NH, Daginawala HF, Purohit HJ, Taori GM. 2015. Rapid diagnosis and simultaneous identification of tuberculous and bacterial meningitis by a newly developed duplex polymerase chain reaction. Indian J Microbiol 55:213–218. doi: 10.1007/s12088-015-0517-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Narayanan S, Parandaman V, Narayanan P, Venkatesan P, Girish C, Mahadevan S, Rajajee S. 2001. Evaluation of PCR using TRC4 and IS6110 primers in detection of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 39:2006–2008. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.5.2006-2008.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nguyen LN, Kox LF, Pham LD, Kuijper S, Kolk AH. 1996. The potential contribution of the polymerase chain reaction to the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Arch Neurol 53:771–776. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550080093017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palomo FS, Rivero MGC, Quiles MG, Pinto FP, Machado A, Carlos Campos Pignatari A. 2017. Comparison of DNA extraction protocols and molecular targets to diagnose tuberculous meningitis. Tuberc Res Treat 2017:5089046. doi: 10.1155/2017/5089046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Portillo-Gomez L, Morris S, Panduro A. 2000. Rapid and efficient detection of extra-pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis by PCR analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 4:361–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rafi W, Venkataswamy M, Nagarathna S, Satishchandra P, Chandramuki A. 2007. Role of IS6110 uniplex PCR in the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: experience at a tertiary neurocentre. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 11:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rana S, Chacko F, Lal V, Arora S, Parbhakar S, Sharma SK, Singh K. 2010. To compare CSF adenosine deaminase levels and CSF-PCR for tuberculous meningitis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 112:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rios-Sarabia N, Hernández-González O, González-Y-Merchand J, Gordillo G, Vázquez-Rosales G, Muñoz-Pérez L, Torres J, Maldonado-Bernal C. 2016. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with meningitis using nested PCR. Int J Mol Med 38:1289–1295. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sastry AS, Sandhya BK, Kumudavathi. 2013. The diagnostic utility of Bact/ALERT and nested PCR in the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Diagn Res 7:74–78. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/5098.2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shankar P, Manjunath N, Mohan K, Prasad K, Behari M, Ahuja G. 1991. Rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis by polymerase chain reaction. Lancet 337:5–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93328-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharma K, Sharma A, Singh M, Ray P, Dandora R, Sharma SK, Modi M, Prabhakar S, Sharma M. 2010. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction using protein b primers for rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Neurol India 58:727. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.72189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kusum S, Aman S, Pallab R, Kumar SS, Manish M, Sudesh P, Subhash V, Meera S. 2011. Multiplex PCR for rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Neurol 258:1781–1787. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kusum S, Manish M, Kapil G, Aman S, Pallab R, Kumar S. 2012. Evaluation of PCR using MPB64 primers for rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis meningitis. Open Access Sci Rep 1:1e4. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharma K, Modi M, Kaur H, Sharma A, Ray P, Varma S. 2015. rpoB gene high-resolution melt curve analysis: a rapid approach for diagnosis and screening of drug resistance in tuberculous meningitis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 83:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sumi M, Mathai A, Reuben S, Sarada C, Radhakrishnan V, Indulakshmi R, Sathish M, Ajaykumar R, Manju Y. 2002. A comparative evaluation of dot immunobinding assay (Dot-Iba) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the laboratory diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 42:35–38. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(01)00342-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baker CA, Cartwright CP, Williams DN, Nelson SM, Peterson PK. 2002. Early detection of central nervous system tuberculosis with the Gen-Probe nucleic acid amplification assay: utility in an inner city hospital. Clin Infect Dis 35:339–342. doi: 10.1086/341494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Causse M, Ruiz P, Gutiérrez-Aroca JB, Casal M. 2011. Comparison of two molecular methods for rapid diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol 49:3065–3067. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00491-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chedore P, Jamieson F. 2002. Rapid molecular diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis using the Gen-probe Amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test in a large Canadian public health laboratory. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 6:913–919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chua H, Tay L, Wang S, Chan Y. 2005. Use of ligase chain reaction in early diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. Ann Acad Med Singapore 34:149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johansen IS, Lundgren B, Tabak F, Petrini B, Hosoglu S, Saltoglu N, Thomsen VØ. 2004. Improved sensitivity of nucleic acid amplification for rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 42:3036–3040. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.3036-3040.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jönsson B, Ridell M. 2003. The Cobas Amplicor MTB test for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex from respiratory and non-respiratory clinical specimens. Scand J Infect Dis 35:372–377. doi: 10.1080/00365540310012244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khan AS, Ali S, Khan MT, Ahmed S, Khattak Y, Irfan M, Sajjad W. 2018. Comparison of GeneXpert MTB/RIF assay and LED-FM microscopy for the diagnosis of extra pulmonary tuberculosis in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Braz J Microbiol 49:909–913. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y, Pang Y, Zhang T, Xian X, Wang X, Yang J, Wang R, Chen M, Chen W. 2017. Rapid diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis with Xpert Mycobacterium tuberculosis/rifampicin assay. J Med Microbiol 66:910–914. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malbruny B, Le Marrec G, Courageux K, Leclercq R, Cattoir V. 2011. Rapid and efficient detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in respiratory and non-respiratory samples. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 15:553–555. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moure R, Martín R, Alcaide F. 2012. Effectiveness of an integrated real-time PCR method for detection of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex in smear-negative extrapulmonary samples in an area of low tuberculosis prevalence. J Clin Microbiol 50:513–515. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06467-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Patel VB, Connolly C, Singh R, Lenders L, Matinyenya B, Theron G, Ndung'u T, Dheda K. 2014. Comparison of Amplicor and GeneXpert MTB/RIF tests for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol 52:3777–3780. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01235-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pink F, Brown T, Kranzer K, Drobniewski F. 2016. Evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol 54:809–811. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02806-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rakotoarivelo R, Ambrosioni J, Rasolofo V, Raberahona M, Rakotosamimanana N, Andrianasolo R, Ramanampamonjy R, Tiaray M, Razafimahefa J, Rakotoson J, Randria M, Bonnet F, Calmy A. 2018. Evaluation of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of smear-negative pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in Madagascar. Int J Infect Dis 69:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rufai SB, Singh A, Singh J, Kumar P, Sankar MM, Singh S, TB Research Team. 2017. Diagnostic usefulness of Xpert MTB/RIF assay for detection of tuberculous meningitis using cerebrospinal fluid. J Infect 75:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Solomons R, Visser D, Friedrich S, Diacon A, Hoek K, Marais B, Schoeman J, van Furth A. 2015. Improved diagnosis of childhood tuberculous meningitis using more than one nucleic acid amplification test. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 19:74–80. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tortoli E, Russo C, Piersimoni C, Mazzola E, Dal M, Pascarella M, Borroni E, Mondo A, Piana F, Scarparo C. 2012. Clinical validation of Xpert MTB/RIF for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Respir J 40:442–447. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00176311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vadwai V, Boehme C, Nabeta P, Shetty A, Alland D, Rodrigues C. 2011. Xpert MTB/RIF, a new pillar in the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis? J Clin Microbiol 49:e02319-10. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02319-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang T, Feng G-D, Pang Y, Yang Y-N, Dai W, Zhang L, Zhou L-F, Yang J-L, Zhan L-P, Marais BJ, Zhao Y-L, Zhao G. 2016. Sub-optimal specificity of modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining for quick identification of tuberculous meningitis. Front Microbiol 7:2096. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zmak L, Jankovic M, Jankovic VK. 2013. Evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF assay for rapid molecular diagnosis of tuberculosis in a two-year period in Croatia. Int J Mycobacteriol 2:179–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmyco.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Haldar S, Sankhyan N, Sharma N, Bansal A, Jain V, Gupta V, Juneja M, Mishra D, Kapil A, Singh UB. 2012. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis GlcB or HspX antigens or devR DNA impacts the rapid diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in children. PloS One 7:e44630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lang AM, Feris-Iglesias J, Pena C, Sanchez JF, Stockman L, Rys P, Roberts GD, Henry NK, Persing DH, Cockerill FR. 1998. Clinical evaluation of the Gen-Probe amplified direct test for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex organisms in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol 36:2191–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.