Abstract

Background:

There is limited information on neurochemical markers being used to support and monitor the affection of motoneurons in patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). The objective of this study was to examine neurochemical markers in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) under treatment with the antisense-oligonucleotide (ASO), nusinersen.

Methods:

We measured markers of axonal degeneration [neurofilament light chain (NfL) and phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain (pNfH)] along with basic CSF parameters in 25 adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients at baseline and after four intrathecal injections of nusinersen. Neurochemical markers were compared with controls. In addition, neurochemical markers in SMA patients were related to the Hammersmith Functional Rating Scale Expanded (HFMSE).

Results:

No significant difference in neurofilament (Nf) values was observed between SMA and control group, neither at baseline nor after four injections of nusinersen. NfL, protein and quotients of albumin (Qalb) increased slightly in SMA patients after the fourth injection. The slight increase of NfL could be related to the development of mild CSF flow change. No relations were observed between changes in Nf and HFMSE.

Conclusion:

We assume that Nf levels in CSF in these patients may result from slow disease progression in this stage of disease, pre-existing loss of motoneurons due to long disease duration besides affection of the LMN only. Therefore, we conclude that Nf levels in CSF do not seem useful as diagnostic and monitoring markers in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients.

Keywords: antisense-oligonucleotide, neurofilaments, nusinersen, SMA

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a monogenetic motoneuron disease (MND) clinically characterized by spinal and bulbar muscle weakness and atrophy. With regard to the onset of clinical symptoms, the achievement of motor milestones and life expectancy, SMA is divided into different subtypes: SMA type 1 represents the infantile and thus the most severe form, while SMA types 2 and 3 are defined as later-onset forms and are characterized as intermediate (SMA type 2) or mild (SMA type 3) types of progression.1

Recently, the antisense-oligonucleotide (ASO), nusinersen, has been approved for treatment for all SMA types. ASOs are synthetic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequences that bind to nucleotide sequences of ribonucleic acid (RNA) strands, alter protein synthesis by several mechanisms of action and therefore provide new opportunities to address previously inaccessible drug targets.2,3

Keeping in mind the current costs for this treatment,4 the semi-invasive administration by lumbar puncture,5,6 as well as lacking data regarding drug efficacy in adolescents and adults, objective markers indicating an early effective treatment response are urgently needed.7

So far, not much information is available on markers for axonal affection in SMA, although some authors suggest that loss of motor neuron cell bodies results from a peripheral ‘dying back’ axonopathy. In mutant SMA mice, massive accumulation of neurofilaments (Nfs) in terminal axons of the remaining neuromuscular junctions could be observed.8 In various neurodegenerative diseases, for example, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), increased cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Nfs were described and their usefulness for diagnosis and prognosis was demonstrated.9–14

Moreover, little is known about whether administration of nusinersen leads to changes in basic CSF parameters which might be used as security readout.

In this study, we aimed to examine neurochemical markers in CSF in later-onset adolescent and adult SMA patients at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen, to evaluate the diagnostic and monitoring value of Nf.

Methods

The primary goals of this study were the following:

(1) Analysis of basic CSF parameters (white cell count, total protein, CSF/serum quotients of albumin (Qalb), oligoclonal bands and lactate), before and during therapy, in comparison with controls. In this context, we see the Qalb as a marker of the blood/CSF barrier and therefore as a marker of CSF flow.15

(2) Analysis of neurochemical markers indicating axonal impairment [neurofilament light chain (NfL) and phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain (pNfH)] in SMA patients under therapy.

(3) Associations of changes in neurochemical markers to changes in motor function measured by the Hammersmith Functional Rating Scale Expanded (HFMSE).16,17 Changes mean the difference between day 63 and day 0, that is, before and after four doses of nusinersen within the SMA patient group.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was approved by the local ethics committees of the centers involved in Ulm and Dresden (approval number at the central study center, University of Ulm 19/12; 2012) and all patients or their relatives (legal guardian/s) gave informed written consent to participate in the study.

Participants and sampling

SMA patients

Patient samples were recruited since the approval of nusinersen in June 2017–June 2018 at the following centers of the MND-NET (German Network for Motoneuron Diseases): Department of Neurology, Ulm University Hospital (Germany) and the Department of Neurology, Technische Universität Dresden (Germany). CSF and serum samples were taken before the intrathecal administration of nusinersen on treatment days 0, 14, 28 and 63. Only samples of days 0 (baseline) and 63 (after four injections) were evaluated.

All patients had genetically confirmed 5q-SMA (deletion in either exon 7 or 8, or both, in the SMN1 gene).

Severity of symptoms were classified as per the HFMSE, a validated rating scale for SMA type 2 and 3 patients. The highest score to reach at HFMSE is 66 points; lower values represent a more severe stage of disease. Scores were raised at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen.

Control group

The control group comprised CSF and serum samples of patients with primary headache disorders, benign intracranial hypertension, idiopathic facial palsy (Bell’s palsy) and psychosomatic diseases. Patients of the control group obtained only one lumbar puncture.

Sample analysis

CSF was collected in polypropylene tubes and was immediately analyzed for routine CSF parameters within 1 hour after lumbar puncture. Cell count and analysis of routine parameters was done as earlier described.18 For measurement of neurodegeneration markers, CSF was frozen within 1 hour after lumbar puncture and stored at −80° until analysis. Commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were used to determine the concentrations of CSF NfL (IBL, Hamburg, Germany) and pNfH (Biovendor, Heidelberg, Germany).11,12 A total of 50 CSF and 50 serum samples of 25 SMA patients, and 25 CSF and 25 serum samples of 25 controls were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described by the median and quartiles. Additionally, the range is presented. Categorical variables were described with absolute and relative frequencies.

For CSF values under the lower limit of detection (LLOD), the value of the LLOD was used for calculation (LLOD NfL < 100 pg/ml, LLOD pNfH < 62.5 pg/ml). To compare datasets of marker concentrations between the SMA patient group and the control group, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used. To compare datasets of marker concentrations as well as motor rating scales within the SMA patient group, the Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. Associations between marker concentrations and between the average levels of fluid analytes and motor rating scores were investigated by the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Because of the explorative character of this study, the results of the statistical tests should not be interpreted as confirmatory: all results of statistical tests have to be interpreted as hypothesis generating only. No adjustment for multiple testing was done. A two-sided p value ⩽ 0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with the software GraphPad Prism 7 and SAS 9.4 under Windows.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the 25 patients, 9 were classified as SMA type 2 and 16 as SMA type 3. Median age was 34.0 years [interquartile range (IQR): 22.5–46.0; range 11.0–60.0]; 11 of the patients were female, 14 were male. SMA type 2 patients reported onset of disease in early childhood; SMA type 3 patients reported onset of disease in childhood or adolescence. Changes in HFMSE were not significantly different in SMA patients after four injections of nusinersen compared with baseline (p = 0.064). It should be pointed out here that this study does not primarily address the evaluation of efficacy of nusinersen in these patients. Patients’ clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics in SMA patients.

| Age |

Disease onset |

Disease duration |

HFMSE |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median, years | Median, years | Median, years | Sum scores at T0 | Sum scores at T1 | |

|

All

SMA patients |

34.0 (IQR: 22.5–46.0; range 11.0–60.0) |

1.0 (IQR: 1.0–7.5; range 0.0–17.0) |

29.0 (IQR: 20.0–42.5; range 10.5–48.0) |

8.0 (IQR: 2.5–37.0; range 0.0–66.0) |

9.0 (IQR: 4.0–39.5; range 0.0–66.0) |

|

SMA

type 2 patients |

25.0 (IQR: 14.5–41.0; range 11.0–48.0) |

0.75 (IQR: 0.25–1.0; range 0.0–1.0) |

24.25 (IQR: 13.63–40.5; range 10.5–48.0) |

2.0 (IQR: 0.0–4.5; range 0.0–7.0) |

4.0 (IQR: 0.0–5.0; range 0.0–7.0) |

|

SMA

type 3 patients |

40.0 (IQR: 30.5–46.0; range 17.0–60.0) |

3.0 (IQR: 1.25–13.0; range 1.0–17.0) |

33.0 (IQR: 21.25–43.75; range 11.0–46.0) |

29.0 (IQR: 8.75–51.75; range 0.0–66.0) |

33.5 (IQR: 9.0–52.0; range 0.0–66.0) |

Data are provided in median values (IQR; range).

HFMSE, Hammersmith Functional Rating Scale Expanded; IQR, interquartile range; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; T0, measures at baseline (before treatment with nusinersen); T1, measures after four injections of nusinersen.

Control group

Median age of the 25 controls was 36.0 years (IQR: 27.0–45.5; range 18.0–65.0). There was no difference in age in the SMA patient group compared with the control group (p = 0.372, two-sample t test).

Basic CSF parameters at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen compared with the control group and within the SMA group

Basic CSF parameters in SMA patients at baseline did not differ compared with the control group in median white cell count (p = 0.572), total protein (p = 0.697), Qalb (p = 0.286) and lactate values (p = 0.160). Patients showed no intrathecal immunoglobulin G (IgG) synthesis [oligoclonal IgG bands (OCB) in CSF]; neither at baseline nor after four injections of nusinersen.

None of the patients in the control group showed any intrathecal IgG synthesis (OCB in CSF) either.

After four injections of nusinersen, routine CSF parameters in SMA patients did not differ in median cell count (p = 0.833), total protein (p = 0.784), Qalb (p = 0.087) and lactate (p = 0.176) compared with the CSF values of the control group.

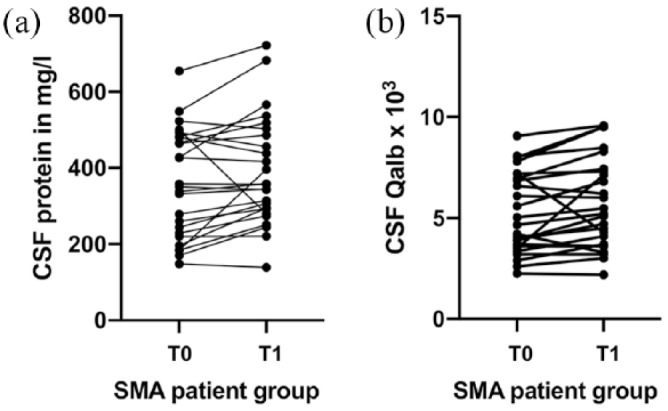

Basic CSF parameters within the SMA patients did not differ at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen in median white cell count (p = 0.489) and lactate (p = 0.831); however, total protein (p = 0.012) and Qalb (p = 0.007) were increased within the SMA patient group after four injections of nusinersen (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

CSF parameters in SMA patients (at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen) and controls.

| White cell count per µl |

Lactate mmol/l |

Total protein mg/l |

Qalb | Intrathecal IgG synthesis (OCB) |

NfL pg/ml |

pNfH pg/ml |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SMA

patients T0 |

1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) | 351 (225–482) | 4.7 (3.6–7.1) | Negative | 263 (143–408) | 62.5 (62.5–62.5) |

|

SMA

patients T1 |

1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 357 (287–495) | 5.2 (3.7–7.4) | Negative | 391 (170–553) | 62.5 (62.5–62.5) |

| Controls | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.6 (1.5–1.7) | 355 (275–473) | 4.1 (3.4–6.0) | Negative | 449 (188–829) | 62.5 (62.5–199) |

Data are median (IQR).

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; NfL, neurofilament light chain; OCB, oligoclonal IgG bands; pNfH, phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain; Qalb, CSF/serum quotients of albumin; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; T0, measures at baseline (before treatment with nusinersen); T1, measures after four injections of nusinersen.

Figure 1.

Individual courses of the CSF total protein and CSF/serum Qalb concentrations at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen in SMA type 2 and 3 patients.

Individual courses of the CSF total protein (a) and CSF/serum Qalb (b) concentrations at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen in SMA type 2 and 3 patients.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; Qalb, quotient of albumin; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; T0, measures at baseline (before treatment with nusinersen); T1, measures after four injections of nusinersen.

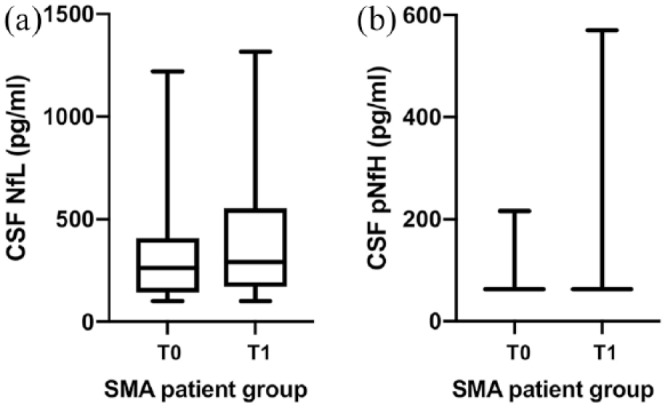

Neurofilament levels (NfL and pNfH) at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen compared with the control group and within the SMA group

Median values of NfL in the SMA patient group did not differ from median NfL values in the control group; neither at baseline (p = 0.102) nor after four injections of nusinersen (p = 0.277).

Only two of 25 SMA patients showed NfL values > 1000 pg/ml (1221 pg/ml, 1164 pg/ml) at baseline, which showed a relatively stable course after four injections of nusinersen (1265 pg/ml, 1317 pg/ml).

Two patients showed NfL levels below the LLOD (<100 pg/ml) at baseline; in one of these patients, a slight increase in NfLs after the fourth injection was detected (284 pg/ml). Within the SMA group, a slight, but significant increase in NfLs after four injections of nusinersen (p = 0.050) was observed [Figure 2(a)].

Figure 2.

Boxplots of NfL and pNfH concentrations in SMA type 2 and 3 patients at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen.

Boxplots of NfL (a) and pNfH (b) concentrations in SMA type 2 and 3 patients at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen. In Figure 2(b), 21 of 25 pNfH values at baseline were below the detection limit (LLOD < 62.5 pg/ml); after four injections of nusinersen, 20 of 25 pNfH values were LLOD < 62.5 pg/ml.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; LLOD, lower limit of detection; NfL, neurofilament light chain; pNfH, phosphorylated neurofilament heavy chain; SMA, spinal muscular atrophy; T0, measures at baseline (before treatment with nusinersen); T1, measures after four injections of nusinersen.

Compared with the control group, pNfH median values also did not differ at baseline (p = 0.126) and after four injections of nusinersen (p = 0.285). In 21 of 25 SMA patients, pNfH values were below the LLOD (<62.5 pg/ml). In 17 of these 21 patients, pNfH values remained under the LLOD after the fourth injection of nusinersen. Three SMA patients with pNfH values above the LLOD at baseline (216 pg/ml, 213 pg/ml, 96 pg/ml) showed a decrease of pNfH values after the fourth injection under the LLOD. Five SMA patients showed an increase in pNfH values after four injections of nusinersen, but median pNfH levels within the SMA patient group did not differ at baseline and after four injections of nusinersen [p = 0.546; Figure 2(b)].

Association of changes in Qalb and total protein with changes in NfLs and pNfHs in SMA patients

While no association was found between changes in Qalb and NfLs (rho = −0.30, p = 0.146), there was a significant association for changes in Qalb and pNfHs (rho = −0.53, p = 0.007). Between changes in total protein and NfLs (rho = −0.03, p = 0.891) and changes in total protein and pNfHs (rho = −0.22, p = 0.286), no relevant associations were detected.

Association of changes in NfLs and pNfHs with changes in HFMSE in SMA patients

No associations were detected between changes in HFMSE and NfLs (rho = −0.08, p = 0.700) and changes in HFMSE and pNfHs (rho = 0.08, p = 0.681).

Discussion

The present study evaluates basic CSF parameters and the diagnostic and monitoring value of the neurochemical markers NfL and pNfH in CSF in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients treated with the ASO nusinersen.

We saw an increase of total protein in CSF and Qalb after the fourth administration of nusinersen in SMA patients, indicating the development of a slight dysfunction in CSF flow. If this can be solely attributed to the nusinersen injection or might be due to repetitive lumbar puncture needs to be further investigated. Nevertheless, one should think of routinely measuring the albumin ratio as a security marker of impaired CSF flow.

No significant difference was observed between NfL and pNfH values between the SMA patient group and the control group, at baseline, nor after the fourth injection of nusinersen. Of note is that several patients had even Nf level below the detection limit of the assay. We saw a slight increase in NfLs within the SMA group after the fourth injection of nusinersen. This, however, might also be related to the development of the slight change in the CSF flow.

In a previous study, we investigated Nfs in CSF in adult SMA patients (n = 7, aged 23–60 years) within a control group. In line with the results of the present study, Nf levels were only elevated in one of seven patients.12 Regarding other MND variants, previous studies showed that Nf levels were not elevated in Kennedy disease (spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy), while in patients with primary lateral sclerosis, high Nf levels could be observed.11,12 This is in line with a further study, in which Nf levels were higher in patients with UMN-dominant ALS than in patients with typical ALS (UMN and LMN).14 Therefore, one might speculate that UMN affection leads to increased Nf levels in CSF while diseases with LMN involvement, such as SMA, do not or less markedly increase Nf levels in CSF.

A further explanation for differences in Nf levels in MND could be disease progression, as high Nf levels have been observed particularly in ALS patients with rapid disease progression.12,14 While disease in sporadic ALS is usually rapidly progressive after symptom onset in adulthood,19 later-onset SMA appears to exhibit slow disease progression.20 In SMA type 2, although already marked by muscular weakness, young children even gain certain motor milestones early in their course, before motor function further declines with partially stable phases in adolescence and adulthood. The clinical course of SMA type 3 is more variable, but also here, motor milestones (up to the ability of walking) are usually developed in childhood, before muscle strength and motor functions diminish over time.21–24

In addition, the long duration of disease in adolescent and adult SMA patients associated with significant impairment of motor function, particularly in SMA type 2 patients (reflected by low scores in HFMSE), must be considered. Therefore, it is important to consider whether low Nf values observed in these patients are also due to pre-existing severe denervation. This can be further supported in our study by only two patients, where we found elevated NfL values, were SMA type 3 patients, one of them still able to walk.

An early and progressive loss of motoneurons occurs in patients with infantile-onset SMA type 1.25,26 First evidence that Nf levels in infants with SMA type 1 may be elevated, and decrease during therapy with nusinersen, was demonstrated in a case report of our group.27 However, further studies are needed to investigate the role of Nfs in children with SMA, particularly SMA type 1. In addition, it is of note that our results are based on an observational period of 2 months in symptomatic adolescent and adult SMA patients, and we cannot draw any conclusions on potential alterations in Nf levels over a longer treatment time. Thus, considering potential delayed treatment effects in these samples, long-term studies on Nf levels in SMA under nusinersen are highly encouraged as subject of future studies. In summary, we found no significant changes in Nfs or motor score and no significant association between changes in Nfs and motor score in adolescent and adult SMA patients after four injections of nusinersen. Therefore, we assume that Nf levels in CSF do not seem useful as diagnostic and monitoring markers in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence that the CSF markers NfL and pNfH are not elevated in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients. We assume that Nf levels in CSF in these patients result from slow disease progression in this stage of disease, preexisting loss of motoneurons due to long disease duration besides affection of the LMN only (in contrast to ALS). Therefore, we conclude that Nf levels in CSF do not seem useful as diagnostic and monitoring markers in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients. However, the situation in younger patients (infants with SMA type 1, children with SMA type 2 and 3) might be different.

As this study provides evidence for the development of mild CSF flow change, expressed in the Qalb, further studies are needed. We recommend monitoring basic CSF parameters as a safety measure during nusinersen therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients for participating in this study.

Thanks to Dagmar Schattauer, Sandra Hübsch, Alice Pabst and Mehtap Bulut-Karac for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Funding: The study was supported in part by grants from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (project FTLDc 01GI1007A, MND-Net 01GI0704); PreFrontAls (01ED1512); the ALS association; the Thierry Latran foundation; the Charcot Foundation for ALS Research; and the Hermann und Lilly Schilling-Stiftung für medizinische Forschung im Stifterverband.

Conflict of interest statement: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

CDW has received honoraria from Biogen as an advisory board member and for lectures and as a consultant from Hoffmann-La Roche.

RG has received honoraria from Biogen as an advisory board member.

JK has received financial research support form TEVA Pharmaceuticals and honoraria as speaker/consultant for AbbVie, Ipsen and AveXis/Novartis.

PL has received financial research support form TEVA Pharmaceuticals and honoraria as speaker/consultant for AbbVie, Atheneum Partners, BIAL, Desitin, Licher MT, Medtronic, Novartis.

SP has received honoraria as speaker/consultant from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Cytokinetics, TEVA Pharmaceuticals, Desitin.

ZU has received honoraria from Biogen as a consultant.

AH, SW, SP, JD, TK and KW report no disclosures.

BW has received honoraria from Biogen for a lecture.

ACL received financial research support from AB Science, Biogen Idec, Cytokinetics, GSK, Orion Pharam, Novartis, TauRx Therapeutics Ltd. and TEVA Pharmaceuticals. He also has received honoraria as a consultant from Mitsubishi, Orion Pharma, Novartis, Teva and as an advisory board member of Biogen, Treeway, and Hoffmann-La Roche.

MO received honoraria as consultant for Biogen, Axon and Fujirebio.

Contributor Information

Claudia D. Wurster, Department of Neurology, University of Ulm, Oberer Eselsberg 45, Ulm 89081, Germany.

René Günther, Department of Neurology, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) Dresden, Dresden, Germany.

Petra Steinacker, Department of Neurology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Jens Dreyhaupt, Institute of Epidemiology and Medical Biometry, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Kurt Wollinsky, Department of Anesthesiology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Zeljko Uzelac, Department of Neurology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Simon Witzel, Department of Neurology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Tugrul Kocak, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Benedikt Winter, Department of Pediatrics, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

Jan C. Koch, Department of Neurology, University Medicine Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany

Paul Lingor, Department of Neurology, University Medicine Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany; Department of Neurology, Klinikum rechts der Isar der Technischen Universität München, Munich, Germany.

Susanne Petri, Department of Neurology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

Albert C. Ludolph, Department of Neurology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany

Andreas Hermann, Department of Neurology, Technische Universität Dresden, Dresden, Germany; German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) Dresden, Dresden, Germany Translational Neurodegeneration Section ‘Albrecht-Kossel’, Department of Neurology, University Medical Center Rostock, University of Rostock, Rostock, Germany German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE) Rostock, Rostock, Germany.

Markus Otto, Department of Neurology, Ulm University, Ulm, Germany.

References

- 1. Lunn MR, Wang CH. Spinal muscular atrophy. Lancet 2008; 371: 2120–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wurster CD, Ludolph AC. Antisense oligonucleotides in neurological disorders. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2018; 11: 1756286418776932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett CF, Baker BF, Pham N, et al. Pharmacology of antisense drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2017; 57: 81–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Lancet Neurology. Treating rare disorders: time to act on unfair prices. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wurster CD, Winter B, Wollinsky K, et al. Intrathecal administration of nusinersen in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients. J Neurol 2019; 266: 183–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mousa MA, Aria DJ, Schaefer CM, et al. A comprehensive institutional overview of intrathecal nusinersen injections for spinal muscular atrophy. Pediatr Radiol 2018; 48: 1797–1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Günther R, Neuwirth C, Koch JC, et al. Motor unit number index (MUNIX) of hand muscles is a disease biomarker for adult spinal muscular atrophy. Clin Neurophysiol 2019; 130: 315–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cifuentes-Diaz C, Nicole S, Velasco ME, et al. Neurofilament accumulation at the motor endplate and lack of axonal sprouting in a spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Hum Mol Genet 2002; 11: 1439–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Skillbäck T, Farahmand B, Bartlett JW, et al. CSF neurofilament light differs in neurodegenerative diseases and predicts severity and survival. Neurology 2014; 83: 1945–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosengren LE, Karlsson JE, Karlsson JO, et al. Patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurodegenerative disease have increased levels of neurofilament protein in CSF. J Neurochem 1996; 67: 2013–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steinacker P, Feneberg E, Weishaupt J, et al. Neurofilaments in the diagnosis of motoneuron diseases: a prospective study on 455 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feneberg E, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Multicenter evaluation of neurofilaments in early symptom onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2018; 90: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lu C-H, Macdonald-Wallis C, Gray E, et al. Neurofilament light chain: a prognostic biomarker in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology 2015; 84: 2247–2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brettschneider J, Petzold A, Süßmuth SD, et al. Axonal damage markers in cerebrospinal fluid are increased in ALS. Neurology 2006; 66: 852–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reiber H. Flow rate of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)—a concept common to normal blood-CSF barrier function and to dysfunction in neurological diseases. J Neurol Sci 1994; 122: 189–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Hagen JM, Glanzman AM, McDermott MP, et al. An expanded version of the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale for SMA II and III patients. Neuromuscul Disord 2007; 17: 693–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glanzman AM, O’Hagen J, McDermott M, et al. Validation of the expanded Hammersmith functional motor scale in spinal muscular atrophy type II and III. J Child Neurol 2011; 26: 1499–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jesse S, Brettschneider J, Süssmuth SD, et al. Summary of cerebrospinal fluid routine parameters in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurol 2011; 258: 1034–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Del Aguila MA, Longstreth WT, McGuire V, et al. Prognosis in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. Neurology 2003; 60: 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaufmann P, McDermott MP, Darras BT, et al. Observational study of spinal muscular atrophy type 2 and 3: functional outcomes over 1 year. Arch Neurol 2011; 68: 779–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaufmann P, McDermott MP, Darras BT, et al. Prospective cohort study of spinal muscular atrophy types 2 and 3. Neurology 2012; 30: 1889–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mercuri E, Finkel R, Montes J, et al. Patterns of disease progression in type 2 and 3 SMA: Implications for clinical trials. Neuromuscular Disord 2016; 26: 126–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Montes J, McDermott MP, Mirek E, et al. Ambulatory function in spinal muscular atrophy: age-related patterns of progression. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0199657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zerres K, Rudnik-Schöneborn S, Forrest E, et al. A collaborative study on the natural history of childhood and juvenile onset proximal spinal muscular atrophy (type II and III SMA): 569 patients. J Neurol Sci 1997; 146: 67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Soler-Botija C, Ferrer I, Gich I, et al. Neuronal death is enhanced and begins during foetal development in type I spinal muscular atrophy spinal cord. Brain 2002; 125: 1624–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kolb SJ, Coffey CS, Yankey JW, et al. Natural history of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Neurol 2017; 82: 883–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Winter B, Guenther R, Ludolph AC, et al. Neurofilaments and tau in CSF in an infant with SMA type 1 treated with nusinersen. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. Epub ahead of print 10 January 2019. DOI: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-320033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]