Short abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers are widely used in the diagnosis of dementia. Even though there is a causal correlation between apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype and amyloid-beta (Aβ), the determination of APOE is currently not supported by national or international guidelines. We compared parallel measured CSF biomarkers of two independent laboratories from 126 patients who underwent clinical dementia diagnostics regarding the APOE genotype. APOE ε4 reduces Aβ1-42 (Aβ42) and Aβ42 to Aβ 1-40 ratio (Aβ42/40) but not total Tau or phospho-181 Tau CSF levels. Higher discordance rates were observed for Aβ42 and subsequently for Aβ42/40 in APOE ε4 carriers compared with noncarriers, and the correlation between the two laboratories was significantly lower for Aβ42 in APOE ε4 positive patients compared with patients without APOE ε4. These observations demonstrate that the evaluation of CSF Aβ biomarkers needs to be interpreted carefully in the clinical context. Different immunoassays, disparate cutoff values, and APOE should be respected.

Keywords: amyloid-beta, APOE, biomarker, discordance, immunoassay, neurochemistry

Introduction

Biomarkers play a pivotal role in the clinical diagnosis of neurodegenerative disorders in particular for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD biomarkers reflect the typical neuropathological hallmarks: hyperphosphorylated tangles and amyloid plaques. While increased phosphorylated tau (p181Tau) and total tau (tTau) indicate the tangle pathology in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), amyloid-beta (Aβ) 1-42 (Aβ42) levels and especially the decreased Aβ42 to amyloid-β 1-40 (Aβ40) ratio (Aβ42/40) embody the cerebral amyloid pathology that can be verified postmortem. The importance of these biomarkers in the clinical diagnosis of AD has been reflected in national (e.g., German) and international guidelines and recommendations (Dubois et al., 2007; McKhann et al., 2011; Cummings et al., 2013; Deuschl and Maier, 2016). Novel research guidelines even more emphasize the significance of these biomarkers (Jack et al., 2018).

We have recently shown that CSF biomarkers measured in different clinically validated and certified laboratories are interpreted discordantly in up to 31.5% of cases for Aβ42 (Vogelgsang et al., 2018), whereas Aβ42/40 seems to be less prone to pre-analytical factors (Gervaise-Henry et al., 2017). It is not clear whether these findings are caused by pre-analytical or analytical interferences.

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 is the most prominent genetic risk factor for late-onset AD (Bertram and Tanzi, 2008). Several studies have shown that APOE ε4 is highly associated with amyloid pathology at any cognitive stage of AD (Mattsson et al., 2018).

We aimed to analyze APOE ε4 as an interfering factor that leads to inconsistent CSF biomarker results under routine clinical conditions. In addition, this study aims to describe the current difficulties in clinical interpretation of CSF Aβ to make physicians aware of pitfalls. Therefore, CSF samples were sent and analyzed at two different, certified, clinical laboratories for biomarker determination.

Methods

Study Design

Within the biomaterial bank of the Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy of the University Medical Center Goettingen, we identified 126 samples from patients between 45 and 90 years where AD-relevant CSF biomarkers were measured in two independent, clinically certified laboratories during routine clinical diagnostic procedures, as described recently (Vogelgsang et al., 2018). CSF biomarkers were measured according to the local standard operating procedures (SOPs), and both laboratories were not informed prior to the study to ensure routine procedures were maintained. No special effort was put in standardizing the SOPs. Biomarkers were measured using commercial and for in vitro diagnostic approved enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs). tTau (Fujirebio Cat# 81572, RRID:AB_2797379) and pTau (Fujirebio Cat# 81574, RRID:AB_2797380) were measured using ELISAs by Fujirebio (Ghent, Belgium), Aβ40 (IBL Cat# RE59651, RRID:AB_2797386) was measured using ELISAs by IBL International (Hamburg, Germany), and Aβ42 (IBL Cat# RE59661, RRID:AB_2797387 and Fujirebio Cat# 81576, RRID:AB_2797385) was measured using ELISAs by IBL and Fujirebio. CSF biomarkers were interpreted according to the corresponding cutoff values of the respective laboratory. Cutoff values were identified and adjusted during their routine validation procedures. At Center 1, cutoff values were 450 pg/ml for Aβ42, 0.05 for the Aβ42/40 ratio, 450 pg/ml for tTau, and 61 pg/ml for pTau. At Center 2, cutoff values were 620 pg/ml for Aβ42, 0.05 for the Aβ42/40 ratio, 320 pg/ml for tTau, and 50 pg/ml for pTau. Cutoff values were not adapted during the study.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed to identify the APOE genotype and accordance for APOE ε4 carriers (E2/E4, E3/E4, and E4/E4) and non APOE ε4 carriers (E2/E2, E2/E3, E3/E3) were compared. We compared each CSF biomarker independently and only included data from participants where the CSF biomarkers were significantly above or below cutoff, identified by ±10% of the respective cutoff value (borderline cutoff zone). Concordance was defined as an identical interpretation of biomarkers in both laboratories (either significantly above or below cutoff), whereas discordance was defined as dissimilar biomarker interpretations in the two corresponding laboratories (above the cutoff in one center and below the cutoff in the other center).

Sample Collection

CSF was collected by a lumbar puncture and stored in polypropylene tubes during the clinical diagnostic procedure. The lumbar puncture was performed in a seated position using a traumatic Quincke needle (BD Diagnostics, Franklin Lakes, NJ) or an atraumatic Sprotte cannula (Pajunk, Geislingen, Germany), according to the preference of the treating physician. The samples were sent immediately to two independent clinical laboratories for CSF biomarker measurements of Aβ42, Aβ40, Aβ42/40, p181Tau, and tTau.

APOE Measurement

APOE genotyping was performed using a quantitative real-time PCR protocol as described previously (Calero et al., 2009), with negative controls for all primer combinations and all PCR reactions run in duplicate. Measurements were carried out using a Stratagene MX3000P Real-Time PCR Cycler (Santa Clara, CA).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism Graph Pad 8 (RRID:SCR_002798). Age was compared using a student’s t-test, and cohort differences for discordant CSF biomarkers and gender were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Correlations were assessed by Spearman correlation and compared after calculating a Fisher r-to-z transformation.

Study Approval

All participants gave their informed consent for biomaterial and data collection prior to inclusion into this study. All data were pseudonymized. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University Medical Center Goettingen (ethical vote 9/2/16). The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Study Cohort

In this study, 54 (42.9%) participants were APOE ε4 carriers with a mean age of 70.4 ± 10.0 years. No APOE ε4 allele was found in 72 (57.1%) participants with a mean age of 66.8 ± 10.3 years. There was a trend in distribution for age (p = .0502) but not for gender (p = .8564) between APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers. CSF biomarker accordance was compared after excluding cases within the borderline cutoff zone (±10%) and age and gender were recalculated for each biomarker. No significant difference in age or gender was observed for any of the analyzed groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Analyzed CSF Biomarkers and Corresponding Patients’ Data.

|

CSF Aβ42 |

CSF Aβ42/40 |

CSF tTau |

CSF pTau |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOE ε4 carrier | Non APOE ε4 carrier | p | APOE ε4 carrier | Non APOE ε4 carrier | p | APOE ε4 carrier | Non APOE ε4 carrier | p | APOE ε4 carrier | Non APOE ε4 carrier | p | |

| Excluded cases | ||||||||||||

| Within borderline cutoff zone (±10%) | 16 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 11 | 17 | 14 | ||||

| Included cases | ||||||||||||

| Concordant (n) (%) | 12 (31.6)a | 46 (79.3)b | <.0001 | 25 (59.5)a | 54 (87.1)b | .0020 | 32 (84.2) | 57 (93.4) | .1761 | 35 (94.6) | 56 (96.6) | .6414 |

| Discordant (n) (%) | 26 (68.4)a | 12 (20.7)b | 17 (40.5)a | 8 (12.9)b | 6 (15.8) | 4 (6.8) | 2 (5.4) | 2 (3.4) | ||||

| Age (years) | 68.4 ± 8.6 | 67.7 ± 9.6 | .5693 | 69.8 ± 10.1 | 66.6 ± 10.2 | .1159 | 68.2 ± 10.8 | 66.3 ± 10.0 | .3782 | 70.7 ± 10.7 | 67.5 ± 10.0 | .1536 |

| Females | 25 | 32 | .3958 | 23 | 35 | >.9999 | 22 | 33 | .8357 | 20 | 30 | .0366 |

| Males | 13 | 26 | 19 | 27 | 16 | 28 | 17 | 28 | ||||

Note. Concordant and discordant cases are shown as absolute numbers and percentage. Significance for age differences were analyzed using t test, concordance, and gender was analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. APOE = apolipoprotein E; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ = amyloid-beta; Aβ42 = Aβ 1-42; Aβ42/40 = Aβ42 to Aβ 1-40 ratio; tTau = total tau; p181Tau = phosphorylated 181tau.

Fisher’s exact test comparing concordance for Aβ42 and Aβ42/40 in APOE ε4 carriers with p = .0147 and non APOE ε4 carriers.

p = .3285.

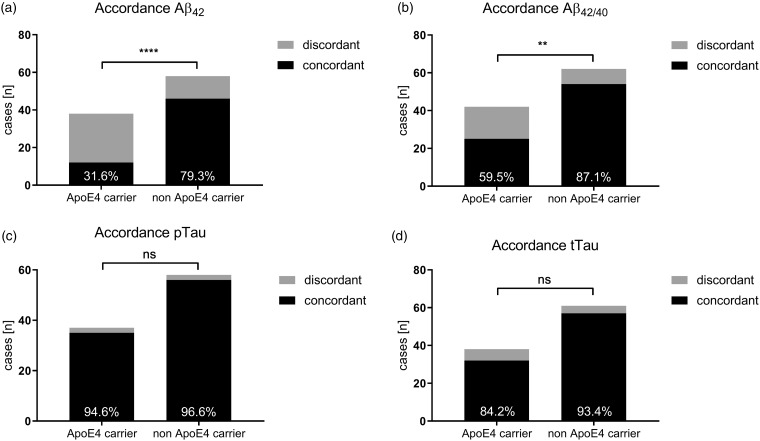

CSF Biomarkers

Accordance rates were compared for all four validated CSF biomarkers: Aβ42, Aβ42/40, tTau, and p181Tau. For Aβ42, 26 (68.4%) APOE ε4 carriers obtained discordant CSF interpretations, whereas only 12 (20.7%) non APOE ε4 carriers received a discordant CSF interpretation (p < .0001). Although there were slightly less discordant cases for Aβ42/40 than Aβ42, there were still significantly more discordant CSF interpretations in APOE ε4 carriers (17 participants [40.5%]) than noncarriers (8 participants [12.9%]; p = .0020). We did not observe any differences in the CSF biomarker interpretation of tTau and p181Tau. tTau was discordantly interpreted in six (15.8%) and four (6.8%) cases in APOE ε4 and non APOE ε4 carriers, respectively (p = .1762). Similarly, two (5.4%) APOE ε4 carriers and two (3.4%) noncarriers received discordant p181Tau interpretations (p = .6414; Figure 1; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Presentation of concordant and discordant CSF biomarkers. **p < .01. ****p < .0001. ns = not significant; APOE = apolipoprotein E; Aβ = amyloid-beta; Aβ42 = Aβ 1-42; Aβ42/40 = Aβ42 to Aβ 1-40 ratio.

In APOE ε4 carriers, the implementation of Aβ42/40 led to a significantly reduced discordancy from 68.4% to 40.5% (p = .0147). Comparable discordant rates for Aβ42 (20.7%) and Aβ42/40 (12.9%) were observed in non APOE ε4 carriers (p = .3285).

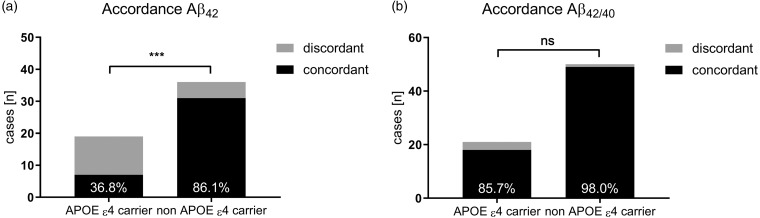

To exclude patients with CSF Aβ concentrations slightly below or above the respective cutoff value, we widened the borderline cutoff zone to ±25%. For Aβ42, 12 APOE ε4 carriers received discordant interpretations and 7 patients were interpreted concordantly. In APOE ε4 noncarriers, only 5 of the 31 participants received discordant biomarker interpretations (p = .0004; Figure 2(a)). Noteworthy, this mismatch was not observed for Aβ42/40. Regarding the latter Aβ peptide ratio, only 3 of the 21 APOE ε4 carriers and 1 of the 50 non APOE ε4 carriers showed discordant results (p = .0746; Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Accordance rate for Aβ42 (a) and Aβ42/40 (b) after application of a ± 25% borderline zone. ***p < .001. ns = not significant; APOE = apolipoprotein E. Aβ = amyloid-beta; Aβ42 = Aβ 1-42; Aβ42/40 = Aβ42 to Aβ 1-40 ratio.

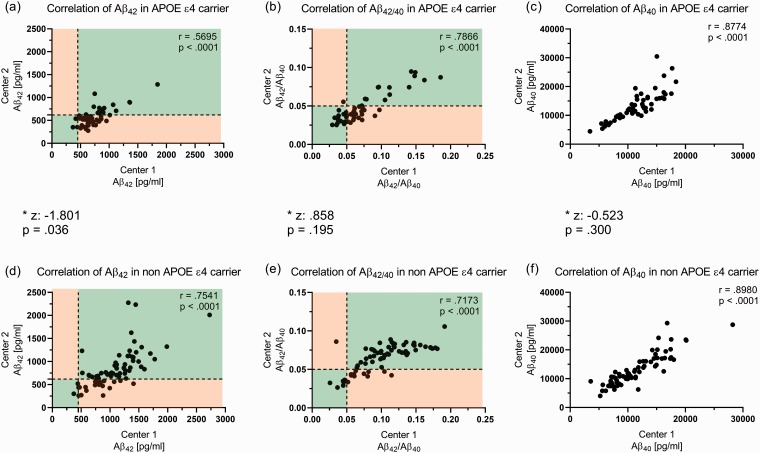

CSF Aβ biomarker concentrations were correlated between Center 1 and Center 2 for APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers separately. Samples with Aβ concentrations above the upper limit of detection were excluded. Aβ42 correlated with r = .5695 between Center 1 and Center 2 in APOE ε4 carriers, whereas the correlation in non APOE ε4 carriers was significantly higher r = .7541 (z = −1.801; p = .036; Figure 3(a) and 3(d)). The correlations between the two centers for APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers were comparable for Aβ42/40 and Aβ40. Aβ42/40 correlated with r = .7886 and r = .7173 in APOE ε4 carriers and non APOE ε4 carriers, respectively (z = 0.858; p = .195; Figure 3(b) and 3(e)). For Aβ40, a correlation of r = .8774 and r = .8980 was calculated in APOE ε4 carriers noncarriers, respectively (z = 0.523; p = .300; Figure 3(c) and 3(f)).

Figure 3.

Correlation of Aβ42, Aβ42/40, and Aβ40 between the two centers for APOE ε4 carriers (a to c) and non APOE ε4 carriers (d to f). Cases with CSF concentrations above the detection limit were excluded; 53 APOE ε4 cases (a to c) and 71 (e and f) or 70 (e) non APOE ε4 cases were included. Correlation was significantly lower (p = .036) in APOE ε4 carriers for Aβ42 between the two centers (a and d), whereas similar correlations could be observed for Aβ42/40 and Aβ40. Concordant CSF biomarkers were defined as consistent CSF levels in both centers above or below the corresponding cutoff values. Areas with concordant cases are colored green, whereas areas with discordant cases are colored orange in Panels (a), (b), (d), and (e). *Comparison of correlation between APOE ε4 carriers and noncarriers for each biomarker after Fisher r-to-z transformation. APOE = apolipoprotein E; Aβ = amyloid-beta; Aβ42 = Aβ 1-42; Aβ42/40 = Aβ42 to Aβ 1-40 ratio.

Aβ42, and consequently Aβ42/40, but not Aβ40, tTau, or p181Tau CSF levels were lower in APOE ε4 carriers (Table 2). Aβ42 CSF levels were 756.3 ± 295.3 pg/ml for APOE ε4 carriers and 1,087.0 ± 411.0 pg/ml for noncarriers at Center 1 (p < .0001) and 604.7 ± 324.9 pg/ml for APOE ε4 carriers and 860.0 ± 447.6 pg/ml for noncarriers at Center 2 (p = .0006). Aβ42/40 CSF levels were 0.0721 ± 0.0363 for APOE ε4 carriers and 0.1021 ± 0.0396 for noncarriers at Center 1 (p < .0001) and 0.0473 ± 0.0189 for APOE ε4 carriers and 0.0658 ± 0.0176 for noncarriers at Center 2 (p < .0001). Aβ40 CSF levels were 11,666 ± 3,747 pg/ml for APOE ε4 carriers and 11,586 ± 4,528 pg/ml for noncarriers at Center 1 (p = .9160) and 13,726 ± 6,099 pg/ml for APOE ε4 carriers and 13,338 ± 6,047 pg/ml for noncarriers at Center 2 (p = .7231; Table 2).

Table 2.

CSF Biomarker Comparison Between APOE ε4 Carriers and Noncarriers for Each Center.

|

CSF Aβ42 |

CSF Aβ42/40 |

CSF Aβ40 |

CSF tTau |

CSF pTau |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration, pg/ml (SD) | p | Concentration, pg/ml (SD) | p | Concentration, pg/ml (SD) | p | Concentration, pg/ml (SD) | p | Concentration, pg/ml (SD) | p | |

| Center 1 | ||||||||||

| APOE ε4 carrier | 756.3 (295.3) | <.0001 | 0.0721 (0.0363) | <.0001 | 11,666 (3,747) | .9160 | 503.6 (325.4) | .0521 | 71.69 (35.91) | .0452 |

| Non APOE ε4 carrier | 1087.0 (411.0) | 0.1021 (0.0396) | 11,586 (4,528) | 392.3 (307.1) | 58.68 (35.56) | |||||

| Center 2 | ||||||||||

| APOE ε4 carrier | 604.7 (324.9) | .0006 | 0.0473 (0.0189) | <.0001 | 13,726 (6,099) | .7231 | 515.1 (370.3) | .0122 | 67.63 (35.22) | .0645 |

| Non APOE ε4 carrier | 860.0 (447.6) | 0.0658 (0.0176) | 13,338 (6,047) | 364.0 (296.2) | 56.04 (34.01) | |||||

Note. APOE ε4 significantly reduces Aβ42 and subsequently Aβ42/40 but not Aβ40, tTau, or pTau. Due to multiple comparison, p values should be considered as α <.005. APOE = apolipoprotein E; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; Aβ = amyloid-beta; Aβ42 = Aβ 1-42; Aβ42/40 = Aβ42 to Aβ 1-40 ratio; SD = standard deviation; tTau = total tau; p181Tau = phosphorylated 181tau.

Discussion

In this study, we identified APOE ε4 as a major factor leading to different Aβ CSF biomarker interpretations in two independent laboratories. However, the APOE genotype did not affect Aβ40, tTau, or p181Tau CSF levels.

The ELISAs used for tTau (Fujirebio), p181Tau (Fujirebio), and Aβ40 (IBL) were identical in both centers, whereas the ELISAs used for Aβ42 were different (IBL and Fujirebio). This could be one reason for a higher discordance in Aβ42 compared with Aβ40, tTau, and p181Tau. However, this study reflects the real life in clinical dementia diagnostics, where physicians have limited impact on the used assays but need to rely on the best laboratory praxis in the corresponding centers. Even though it is not unexpected that different immunoassay show less concordance than identical immunoassays, the impact of APOE ε4 on the accordance level is surprising. This effect was consistent even after excluding more some samples with CSF biomarkers close to the corresponding cutoff. Despite a substantially broader borderline cutoff zone (±25%), we still observe a significant discordant Aβ42 interpretation in APOE ε4 carriers compared with APOE ε4 noncarriers. This finding indicates that a molecular interaction of APOE ε4 with Aβ42 or one of the two ELISAs significantly contributes to the observed interlaboratory mismatch for the measurement of Aβ42 in CSF. Accordingly, our observation is unlikely explained only by interlaboratory differences in cutoff values.

A further comparison between both immunoassays could improve the diagnostic accuracy in clinical laboratories; however, it is not trivial to determine the exact Aβ levels in CSF and determine whether one immunoassay is superior to the other one.

Different functions of APOE have been described within the pathologic pathway of AD (reviewed in Bertram and Tanzi, 2008). Besides assisting the transportation of Aβ through the blood brain barrier, there is strong evidence that APOE interacts with Aβ peptides (Naslund et al., 1995; Tiraboschi et al., 2004) and promotes conformational changes into β sheets (Wisniewski and Frangione, 1992). As described by Strittmatter et al., APOE in general (Strittmatter et al., 1993a), but APOE ε4 even faster than APOE ε3 (Strittmatter et al., 1993b), binds to Aβ peptides. This could affect the CSF biomarker measurements using enzyme-based immunoassays. We observed a reduced correlation between the ELISAs by IBL and Fujirebio in APOE ε4 carriers compared with noncarriers, supporting the hypothesis that APOE ε4 interacts with Aβ42 or one of the corresponding ELISAs.

Different studies have compared blood and CSF APOE levels. Wahrle et al. (2007) reported an age-dependent effect on general APOE levels in CSF, whereas the dementia stage (as measured by the clinical dementia rating), the APOE genotype, gender, and race did not affect CSF APOE levels. Interestingly, CSF but not plasma APOE levels showed an APOE genotype independent association with Aβ42 concentrations in CSF (Cruchaga et al., 2012).

According to the study by Mayeux et al. (1998), without additional CSF or positron emission tomography (PET) biomarkers, APOE has a sensitivity of 65% and specificity of 68% for the detection of AD. Due to the limited diagnostic significance, national and international guidelines do not include APOE genotyping in the clinical diagnostics (Deuschl and Maier, 2016). However, with the knowledge of a significant interference of APOE and Aβ biomarker in the CSF, the determination of patients APOE genotype should be considered more important.

This study does not intend to explain any causal relation between APOE and Aβ but aims to call attention to a critical interpretation of Aβ CSF biomarkers in routine patient care and research. As CSF biomarkers are gaining importance in the etiological diagnosis of dementia, misinterpreted biomarkers have a significant impact on the clinical and therapeutic procedure (e.g., medication). Thus, false-negative CSF biomarker results could lead to insufficient treatment of AD patients.

Novel data suggest higher reproducibility CSF biomarkers using fully automated analyzers (Hansson et al., 2018). However, further validation studies are needed to support the superiority of fully automated analyzers compared with classical ELISAs.

The determination of the APOE genotype could be a diagnostic benefit not only as a risk factor for AD but also as an interfering factor for CSF Aβ biomarker measurements, which should be handled and interpreted carefully, in particular in APOE ε4 positive patients. Due to the lacking gold standard (post mortem analysis), it is difficult to predict the superiority of one ELISA in this study. However, CSF Aβ concentration slightly above or below the corresponding cutoff value should be questioned even more in APOE ε4 positive patients. We recommend additional diagnostic procedures, for example, amyloid-PET if CSF biomarkers and clinical or neuropsychological examinations are conflicting. Moreover, this study strengthens the diagnostic use of Aβ42/40 to reduce insecure CSF biomarker interpretations.

Different immunoassays and cutoff points can render discordance between different laboratories. APOE ε4 should be taken into account when applying round robin studies to harmonize cutoff values between different centers.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

The major limitation of this study is the missing of harmonized SOPs, different infrastructures, and immunoassays. However, we did not address these aspects to outline the practical difficulties in the real-life clinical usage of biomarkers. The strength of this study is the naturalistic character of this analysis.

Summary

CSF biomarker misinterpretations are a widely known problem in clinical practice. This study shows that, besides different immunoassays and cutoff points, the APOE status contributes significantly to discordant CSF Aβ biomarkers. APOE ε4 increases the risk of misinterpreting CSF Aβ42.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ulrike Heinze and Anke Jahn-Brodmann for the data management and Oliver Wirths for the performance of APOE genotyping. We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation and the Open Access Publication Funds of the Göttingen University.

Authors’ Contributions

J. V. and J. W. designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. D. W. and R. V. supported with the interpretation, read and approved the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Jens Wiltfang is supported by an Ilídio Pinho professorship and iBiMED (UID/BMI/04501/2013) and Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) project PTDC/DTP_PIC/5587/2014 at the University of Aveiro, Portugal.

References

- Bertram L., Tanzi R. E. (2008). Thirty years of Alzheimer’s disease genetics: The implications of systematic meta-analyses. Nat Rev Neurosci, 9, 768–778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calero O., Hortigüela R., Bullido M. J., Calero M. (2009). Apolipoprotein E genotyping method by Real Time PCR, a fast and cost-effective alternative to the TaqMan® and FRET assays. J Neurosci Methods, 183, 238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga C., Kauwe J. S. K., Nowotny P., Bales K., Pickering E. H., Mayo K., Bertelsen S., Hinrichs A., Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, Fagan A. M., Holtzman D. M., Morris J. C., Goate A. M. (2012). Cerebrospinal fluid APOE levels: An endophenotype for genetic studies for Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet, 21, 4558–4571. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22821396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. L., Dubois B., Molinuevo J. L., Scheltens P. (2013). International Work Group criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Med Clin North Am, 97, 363–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschl G., Maier W. (2016). S3-Leitlinie “Demenzen” Retrieved from http://www.dgn.org/leitlinien

- Dubois B., Feldman H. H., Jacova C., DeKosky S. T., Barberger-Gateau P., Cummings J., Delacourte A., Galasko D., Gauthier S., Jicha G., Meguro K., O’Brien J., Pasquier F., Robert P., Rossor M., Salloway S., Stern Y., Visser P. J., Scheltens P. (2007). Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol, 6, 734–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervaise-Henry C., Watfa G., Albuisson E., Kolodziej A., Dousset B., Olivier J.-L, Jonveaux T. R., Malaplate-Armand C. (2017). Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42/Aβ40 as a means to limiting tube- and storage-dependent pre-analytical variability in clinical setting. J Alzheimer’s Dis, 57, 437–445. Retrieved from http://www.medra.org/servlet/aliasResolver?alias=iospress&doi=10.3233/JAD-160865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson O., Seibyl J., Stomrud E., Zetterberg H., Trojanowski J. Q., Bittner T., Lifke V., Corradini V., Eichenlaub U., Batrla R., Buck K., Zink K., Rabe C., Blennow K., Shaw L. M., Swedish BioFINDER Study Group, & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. (2018). CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-β PET and predict clinical progression: A study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimer’s Dement, 14, 1470–1481. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29499171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack C. R., Bennett D. A., Blennow K., Carrillo M. C., Dunn B., Haeberlein S. B., Holtzman D. M., Jagust W., Jessen F., Karlawish J., Liu E., (2018). NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement, 14, 535–562. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattsson N., Groot C., Jansen W.J., Landau S.M., Villemagne V.L., Engelborghs S., Mintun M.M., Lleo A., Molinuevo J.L., Jagust W.J., Frisoni G.B. (2018) Prevalence of the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele in amyloid β positive subjects across the spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement, 14, 913–924. Retrieved from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1552526018300633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeux R., Saunders A. M., Shea S., Mirra S., Evans D., Roses A. D., Hyman B. T., Crain B., Tang M. X., Phelps C. H. (1998). Utility of the apolipoprotein E genotype in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med, 338, 506–511. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9468467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G. M., Knopman D. S., Chertkow H., Hyman B. T., Jack C. R., Kawas C. H., Klunk W. E., Koroshetz W. J., Manly J. J., Mayeux R., Mohs R. C., Morris J. C., Rossor M. N., Scheltens P., Carrillo M. C., Thies B., Weintraub S., Phelps C. H. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement, 7, 263–269. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J., Thyberg J., Tjernberg L. O., Wernstedt C., Karlstrom A. R., Bogdanovic N., Gandy S. E., Lannfelt L., Terenius L., Nordstedt C. (1995). Characterization of stable complexes involving apolipoprotein E and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neuron, 15, 219–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter W. J., Saunders A. M., Schmechel D., Pericak-Vance M., Enghild J., Salvesen G. S., Roses A. D. (1993. a). Apolipoprotein E: High-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci, 90, 1977–1981 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2361441%5Cnhttp://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8446617%5Cnhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC46003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strittmatter W. J., Weisgraber K. H., Huang D. Y., Dong L.-M, Salvesen G. S., Pericak-Vance M., Schmechel D., Saunders A. M., Goldgaberii D., Roses A. D. (1993. b). Binding of human apolipoprotein E to synthetic amyloid, B peptide: Isoform-specific effects and implications for late-onset Alzheimer disease. Med Sci, 90, 8098–8102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiraboschi P., Hansen L. A., Masliah E., Alford M., Thal L. J., Corey-Bloom J. (2004). Impact of APOE genotype on neuropathologic and neurochemical markers of Alzheimer disease. Neurology, 62, 1977–1983. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15184600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelgsang J., Wedekind D., Bouter C., Klafki H.-W, Wiltfang J. (2018). Reproducibility of Alzheimer’s disease cerebrospinal fluid-biomarker measurements under clinical routine conditions. J Alzheimers Dis, 62, 203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahrle S. E., Shah A. R., Fagan A. M., Smemo S., Kauwe J. S. K., Grupe A., Hinrichs A., Mayo K., Jiang H., Thal L. J., Goate A. M., Holtzman D. M. (2007). Apolipoprotein E levels in cerebrospinal fluid and the effects of ABCA1 polymorphisms. Mol Neurodegener, 2, 7 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17430597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski T., Frangione B. (1992). Apolipoprotein E: A pathological chaperone protein in patients with cerebral and systemic amyloid. Neurosci Lett, 135, 235–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]