ABSTRACT

Introduction

Hand hygiene practice, as correctly said, is the backbone of infection control and it has been proven to limit infections in hospital settings. Currently most healthcare facilities monitor hand hygiene compliance by direct observation technique.

We decided to use video surveillance as a tool to monitor hand hygiene compliance and its impact.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted over a period of 6 months from March 2018 to August 2018 at Apex Hospital, Jaipur, India.

We compared direct observation of ICU, High Dependency Units, and Emergency with video surveillance in these areas.

Results and Observations

In this study, direct observation and video audit were compared from March 2018 to August 2018. During March to August, average compliance rates of direct observation and video surveillance were compared. In month of march, they were 67% and 20%, respectively and in the month of august, they were 81% and 47%, respectively.

Conclusion

In our study, We can conclude in our study that video monitoring combined with direct observation can produce a significant and sustained improvement in hand hygiene compliance and can improve quality of patient care.

How to cite this article

Sharma S, Khandelwal V, Mishra G. Video Surveillance of Hand Hygiene: A Better Tool for Monitoring and Ensuring Hand Hygiene Adherence. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23(5):224–226.

Keywords: Compliance monitoring, Hand hygiene, Video surveillance, WHO five key moments

INTRODUCTION

Hand hygiene practice, as correctly said, is the backbone of infection control and it has been proven to limit infections in hospital settings.1 One of the most important component of infection control program is to monitor hand hygiene compliance.2,3 WHO recommends regular hand hygiene compliance monitoring to improve the hand hygiene compliance. WHO recommends five key moments of hand hygiene, these are:

Before touching a patient

Before clean/aseptic procedures

After body fluid exposure/risk

After touching a patient

Currently most healthcare facilities monitor hand hygiene compliance by direct observation technique, as this is considered “gold standard”.6 But this approach has its own limitations. Direct observation technique is most of the time affected by observer and other kind of biases, which can influence the action of the person being observed and sometimes does not give us the actual data of hand hygiene compliance.6–9 It is observed that direct observation gives us false high results than actual hand hygiene compliance. Furthermore, we cannot rely solely on direct observation technique for hand hygiene compliance monitoring as it has sampling bias also6 and sometimes the compliance vary from 4 to 100%.4 Video surveillance for compliance monitoring had been observed in many different industries like sports etc., as well as in hospital settings too for different purposes.11 Some studies have used video monitoring for hand hygiene monitoring as well.12,13 We also decided to use video surveillance as a tool to monitor hand hygiene compliance and its impact.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted over a period of 6 months from March 2018 to August 2018 at Apex Hospital, Jaipur, India. Previously, we were using direct observation technique as the sole monitoring tool for hand hygiene compliance. We gave regular training for hand hygiene as before. No extra training was done in the study period.

For hand hygiene compliance monitoring, we used following formula:

We compared direct observation of ICU, high dependency unit (HDU), and emergency (ER) with video surveillance in these areas. Direct observation was done for 30 minutes in each area, cumulatively 4 hours/day. From March onward, video surveillance was introduced for hand hygiene compliance monitoring and it was prior informed to all doctors and staff. Video surveillance was also done for the same duration i.e. 30 minutes. During video surveillance, no observer was physically present in those areas.

RESULTS AND OBSERVATIONS

In this study, direct observation and video audit were compared from March 2018 to August 2018 between doctors, nurses, and housekeeping staff (Tables 1 to 6).

Table 1.

Comparison of direct observation vs video surveillance (March)

| % (DO) | % (VS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU | Doctors | 72 | 20 |

| Nursing staff | 72 | 21 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 61 | 15 | |

| HDU | Doctors | 68 | 20 |

| Nursing staff | 71 | 22 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 60 | 17 | |

| Emergency | Doctors | 70 | 22 |

| Nursing staff | 68 | 23 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 64 | 18 |

Table 6.

Comparison of direct observation vs video surveillance (August)

| % (DO) | % (VS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU | Doctors | 85 | 50 |

| Nursing Staff | 83 | 50 | |

| Housekeeping Staff | 75 | 45 | |

| HDU | Doctors | 84 | 48 |

| Nursing Staff | 83 | 50 | |

| Housekeeping Staff | 74 | 42 | |

| Emergency | Doctors | 85 | 48 |

| Nursing Staff | 84 | 49 | |

| Housekeeping Staff | 74 | 40 |

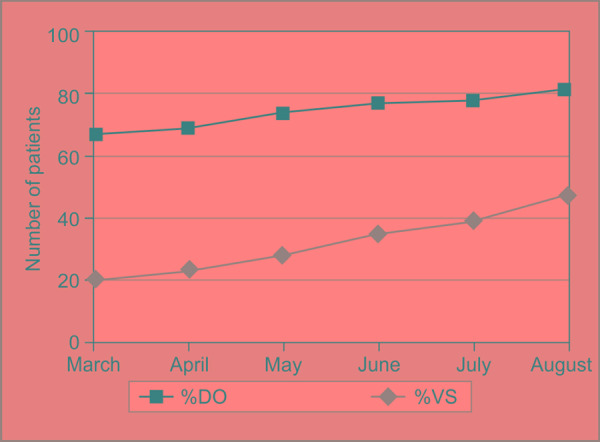

During March to August, average compliance rates of direct observation and video surveillance were compared. In month of march, they were 67% and 20%, respectively and in the month of august, they were 81% and 47%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Compliance of hand hygiene according to direct observation (DO) and video surveillance (VS)

DISCUSSION

In our study, we observed WHO five key moments of hand hygiene in our hand hygiene monitoring. This study demonstrates that the hand hygiene compliance rate by direct observation technique and by video surveillance showed significant difference at the starting of study7,12,14–18 but this difference started to reduce later in the study, though not completely.12,13

Direct observation technique can have a disadvantage of observer bias, which can be due to multiple factors.7,15–17 The study of Armellino and colleagues showed reduced selection bias in video surveillance in comparison to direct observation that falsely increased rates due to Hawthorene effect or observer effect.12,13

Table 2.

Comparison of direct observation vs video surveillance (April)

| % (DO) | % (VS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU | Doctors | 71 | 25 |

| Nursing staff | 76 | 25 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 62 | 17 | |

| HDU | Doctors | 68 | 23 |

| Nursing staff | 71 | 25 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 60 | 18 | |

| Emergency | Doctors | 70 | 28 |

| Nursing staff | 68 | 29 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 64 | 18 |

Table 3.

Comparison of direct observation vs video surveillance (May)

| % (DO) | %(VS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU | Doctors | 78 | 30 |

| Nursing staff | 80 | 33 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 68 | 22 | |

| HDU | Doctors | 76 | 29 |

| Nursing staff | 79 | 30 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 65 | 20 | |

| Emergency | Doctors | 75 | 32 |

| Nursing staff | 78 | 35 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 65 | 21 |

Table 4.

Comparison of direct observation vs video surveillance (June)

| % (DO) | % (VS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU | Doctors | 81 | 38 |

| Nursing staff | 82 | 39 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 71 | 30 | |

| HDU | Doctors | 79 | 37 |

| Nursing staff | 80 | 35 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 67 | 29 | |

| Emergency | Doctors | 79 | 38 |

| Nursing staff | 82 | 38 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 69 | 29 |

Table 5.

Comparison of direct observation vs video surveillance (July)

| % (DO) | % (VS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU | Doctors | 82 | 42 |

| Nursing staff | 81 | 45 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 72 | 38 | |

| HDU | Doctors | 80 | 40 |

| Nursing staff | 81 | 39 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 70 | 37 | |

| Emergency | Doctors | 82 | 39 |

| Nursing staff | 83 | 38 | |

| Housekeeping staff | 70 | 35 |

We observed improved hand hygiene compliance overall, not just in presence of observer or camera.12,13 Staff was previously aware of the ongoing video surveillance but significant improvement was seen in subsequent months when feedback was given in monthly infection control meetings where difference in performance metrics between direct and video surveillance monitoring were displayed.

Although the purpose of this study was to observe hand hygiene compliance monitoring by video surveillance, we saw improvement in other areas of infection control practices, such as, standard precaution, aseptic technique during procedures etc. Employee privacy was maintained during the surveillance. Video tapes have been archived and can be further analyzed, which is the additional advantage of video monitoring.

We can conclude in our study that video monitoring combined with direct observation can produce a significant and sustained improvement in hand hygiene compliance and can improve quality of patient care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our hospital doctors, nirsing staff and housekeeping staff for their assistance.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Marra AR,, Moura DF,, Paes AT,, dos Santos OF,, Edmond MB. Measuring rates of hand hygiene adherence in the intensive care setting: a comparative study of direct observation, product usage, and electronic counting devices. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;;31::796-–801.. doi: 10.1086/653999. doi: 10.1086/653999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyce JM,, Pittet D. Guideline for hand hygiene in health-care settings: recommendations of the healthcare infection control practices advisory committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA hand hygiene task force. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;;23::S3-–S40.. doi: 10.1086/503164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pittet D,, Allegranzi B,, Boyce JM. The World Health Organization guidelines on hand hygiene in health care and their consensus recommendations. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;;30::611-–622.. doi: 10.1086/600379. doi: 10.1086/600379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erasmus V,, Daha TJ,, Brug H,, Richardus JH,, Behrendt MD,, et al. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;;31::283-–94.. doi: 10.1086/650451. doi: 10.1086/650451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sax H,, Allegranzi B,, Uçkay I,, Larson E,, Boyce J,, Pittet D. ‘My five moments for hand hygiene’: a user-centred design approach to understand, train, monitor and report hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect. 2007;;67::9-–21.. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas JP,, Larson EL. Measurement of compliance with hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect. 2007;;66::6-–14.. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.11.013. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adair JG. The Hawthorne effect: a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J Appl Psychol. 1984;;69::334-–345.. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.69.2.334. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckmanns T,, Bessert J,, Behnke M,, Gastmeier P,, Ruden H. Compliance with antiseptic hand rub use in intensive care units: the Hawthorne effect. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;;27::931-–934.. doi: 10.1086/507294. doi: 10.1086/507294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carson F. Utilizing video to facilitate reflective practice: developing sports coaches. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2008;;3::381-–390.. doi: 10.1260/17479540878623851. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smeeton SJ,, Hibbert JR,, Stevenson K,, Cumming J,, Williams AM. Can imaginary facilitate improvements in anticipation behavior? Psychol Sport Exerc. 2013;;14::200-–210.. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.10.008. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinovitch SN,, Feldman F,, Yang Y,, Schonnop R,, Leung PM,, Sarraf T,, et al. Video capture of the circumstances of falls in elderly people residing in long-term care: an observational study. Lancet. 2013;;381::47-–54.. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61263-X. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61263-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armellino D,, Hussain E,, Schilling ME,, Senicola W,, Eichorn A,, Dlugacz Y,, et al. Using high technology to enforce low-technology safety measures: the use of third party remote video auditing and real-time feedback in healthcare. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;;54::1-–7.. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis201. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Armellino D,, Trivedi M,, Law I,, Singh N,, Schilling ME,, Hussain E,, et al. Replicating changes in hand hygiene in a surgical intensive care unit with remote video auditing and feedback. Am J Infect Control. 2013;;41::925-–927.. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.12.011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen SH,, Gerding DN,, Johnson S,, Kelly CP,, Loo VG,, McDonald LC,, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 Update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;;31::431-–455.. doi: 10.1086/651706. doi: 10.1086/651706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegel JD,, Rhinehart E,, Jackson M,, Chiarello L. Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;;35((10 Suppl 2):):S65-–164.. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitby M,, McLaws ML,, Ross MW. Why healthcare workers don't wash their hands: a behavioral explanation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;;27::484-–492.. doi: 10.1086/503335. doi: 10.1086/503335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boudjema S,, Dufour JC,, Soto Aladro A,, Desquerres I,, Brouqui P. Medi Hand Trace®: A tool for measuring and understanding hand hygiene adherence. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;;20::22-–28.. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srigley JA,, Furness CD,, Baker GR,, Gardam M. Quantification of the Hawthorne effect in hand hygiene compliance monitoring using an electronic monitoring system: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;;23::974-–980.. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003080. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]