Abstract

Acute hepatitis remains a diagnostic challenge, and numerous infectious, metabolic and autoimmune diseases need to be effectively excluded. We present a case of a young woman with malaise, fever, jaundice and deranged liver function tests. Testing for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) virus capsid antigen IgM/IgG was positive. Total IgG was elevated, along with positive serology for anti-hepatitis A virus (HAV)-IgM, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) and soluble liver antigen (SLA) leading to the differential diagnosis of acute hepatitis A and autoimmune hepatitis. No specific treatment was started and liver function gradually improved. At week 4, HAV IgG and IgM were negative. At month 4, ANA and SLA were negative and total IgG normalised; EBV nuclear antigen became positive. Testing for EBV is an investigation required at baseline in acute hepatitis and physicians should carefully evaluate serological results, including those for viral and autoimmune hepatitis that may be falsely positive in infectious mononucleosis.

Keywords: hepatitis other, hepatitis and other GI infections, immunology

Background

Acute hepatitis is a common reason for presentation in clinical practice. Deranged liver function tests (LFTs) with jaundice require a more urgent work-up and numerous infectious, metabolic, toxic and autoimmune diseases need to be effectively excluded. Serological tests are among the initial investigations in these patients. Here we present a case of a young woman, where serologies for acute hepatitis A and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) were false positive during acute Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 38-year-old woman was admitted for inpatient treatment because of jaundice and generalised itching for 1 day. She had a 3-week history of fever (>39°C), dry cough and cervical lymphadenopathy. She was initially treated by her family doctor. Test for heterophile antibodies (Monospot) was negative. Due to persistent cough and high fever and suspected atypical pneumonia, treatment with clarithromycin had been started 1 week before admission. In the following days, she experienced vomiting, diarrhoea and lower abdominal pain. Clarithromycin was discontinued after 2 days due to adverse events and possible underlying viral cause. A review of the neurological, cardiovascular and urogenital systems was unremarkable. She worked as a teacher in a professional school and lived alone. She reported that she did not smoke, consume alcohol or use illicit drugs. She had no sick contacts or exposure to animals as well as relevant travel history. On physical examination, she appeared well. Her temperature was 37.1°C (98.78°F), blood pressure 123/83 mm Hg, heart rate 123 beats per minute and the oxygen saturation was 99% while she was breathing ambient air. The heart sounds were normal, and the lungs were clear. The abdomen was soft, with no organomegaly. At the time of presentation, there was no lymphadenopathy or petechiae on the palate or skin rash.

Investigations

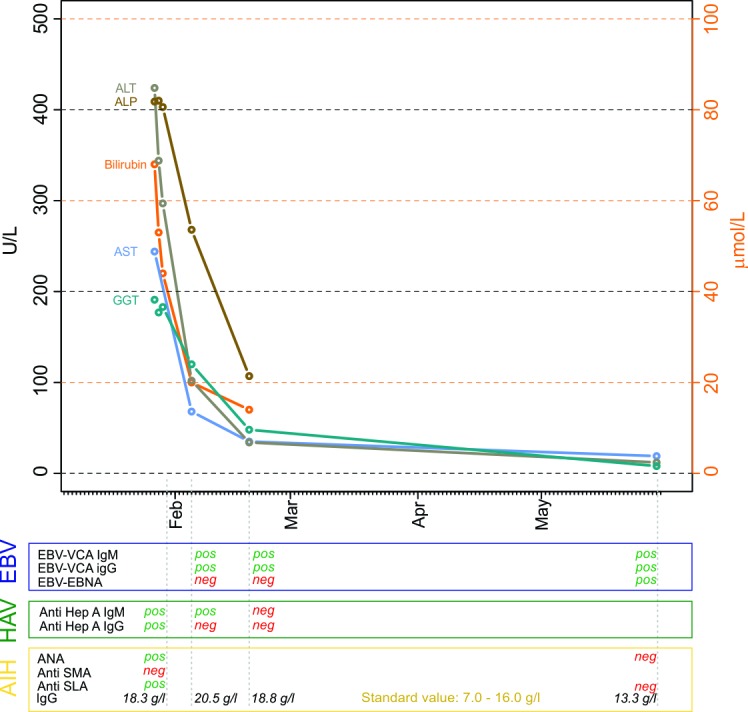

Blood investigations (figure 1) revealed a platelet count of 294 109/L (normal range: 143–400 109/L), moderate haemolysis (haemoglobin 124 g/L, normal range: 117–153 g/L; mean corpuscular volume 92.1 fl, normal range: 80–100 fl; haptoglobin <0.10 g/L, normal range: 0.3–2.0 g/L; lactate dehydrogenase 1095 U/L, normal range: 240–480 U/L) and lymphocytosis (7.31 109/L, normal range: 1.50–4.00 109/L; white cell count 11.10 109/L, normal range: 3.0–9.6 109/L). A blood film showed lymphocytosis with small lymphocytes, partially with atypical appearance, as well as some plasma cells. Furthermore, total bilirubin was 68 μmol/L (upper normal limit (UNL) <21 μmol/L; direct bilirubin 60 μmol/L), aspartate aminotransferase 244 U/L (UNL <35 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase 424 IU/L (UNL <35 IU/L), γ-glutamyl transferase 191 IU/L (UNL <40 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase 409 IU/L (UNL 35–105 IU/L), albumin 38 g/L (range 40–49 g/L) and international normalised ratio 1.0 (<1.2).

Figure 1.

Time course of liver function tests and Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis A virus (HAV), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) serology. Total bilirubin: upper normal limit (UNL) <21 μmol/L, alanine aminotransferase (AST) UNL <35 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) UNL <35 IU/L, γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT) UNL <40 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) UNL 35–105 IU/L. ANA, antinuclear antibody; EBNA, EBV nuclear antigen; neg, negative; pos, positive; SLA, soluble liver antigen; SMA, smooth muscle antibody; VCA, virus capsid antigen.

Serological tests for hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV) as well as HIV and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were negative. Serological testing for hepatitis A virus (HAV) revealed a positive titre for anti-HAV IgM (1.15, UNL <0.8) consistent with subacute HAV infection (figure 1). Serological testing for EBV was compatible with acute EBV infection with positive anti-virus capsid antigen (VCA) IgG and IgM and negative anti-EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA). Liver autoimmune serology was positive for anti-soluble liver antigen (SLA, positive titre ≥20 E/mL) and antinuclear antibodies (ANAs, positive titre ≥1:320) but negative for smooth muscle antibodies (positive titre ≥1:80).

Abdominal ultrasound showed normal liver size, morphology and perfusion, with a normal intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree, but increased spleen size (pole diameter of 14 cm).

Differential diagnosis

This young and otherwise healthy woman presented with fever, jaundice, deranged LFTs, haemolytic anaemia and splenomegaly. We considered infectious and non-infectious causes for painless jaundice.

Infectious causes

EBV infection or infectious mononucleosis presents with lymphadenopathy (100%), fever (98%), pharyngitis (85%) and fatigue. The majority of patients also develops liver function abnormalities.1 Our patient had splenomegaly, which is seen in up to 50% of patients with infectious mononucleosis.2 Peripheral blood count showed reactive lymphocytosis, as well as haemolytic anaemia, typical laboratory signs of infectious mononucleosis.

Diagnosis of EBV is usually confirmed by serology. Heterophile antibodies are produced during EBV infection and react to antigens from phylogenetically unrelated species. A positive test for heterophile antibodies (for instance, the ‘Monospot test’, testing for agglutination of sheep erythrocytes) is considered diagnostic for EBV. The sensitivity of the Monospot test is only 85% and in cases with high clinical suspicion as in our patient, EBV specific antibodies can be tested.

Anti-EBV VCA antibodies are typically present at onset of symptoms, whereas anti-EBV VCA-IgM turns negative after several months, IgG antibodies remain positive for life and are a marker for past EBV infection. EBNA appears 6–12 weeks after onset of symptoms when the virus establishes latency. In our patient, anti-EBV VCA-IgM 2 weeks after presentation and seroconversion of EBNA effectively prove EBV infection.3

Acute HAV infection typically begins abruptly with malaise, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. Within a few days to a week, jaundice occurs. In our patient, initial serological testing showed positive results for anti-hepatitis A IgM antibodies, a finding that would be considered diagnostic for acute hepatitis A infection.4

Other viral causes associated with hepatitis including CMV (<4 arbitrary units (AE)/mL, UNL=6AE), HIV (negative HIV Ag/Ab Combo Screening), HBV (HBsAg (surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus) negative, anti-HBc IgG/IgM negative), HCV (anti-HCV negative) could be excluded. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) serology was not performed. The clinical course with acute hepatitis, negative travel history/exposure is not suggestive for pathogens such as Brucella sp, Bartonella sp, Coxiella burnetii or Mycobacteria tuberculosis complex.

Non-infectious causes

Liver involvement of a haematological or solid malignancy could also explain jaundice, fever, malaise, anaemia and splenomegaly. However, the young age of our patient, the subacute presentation and the normal abdominal ultrasound effectively ruled these out.

AIH also leads to jaundice and deranged LFTs, especially in young females. Most patients are asymptomatic or oligosymptomatic with an undulating disease course, but an acute or subacute presentation is also possible in AIH. Fever, lymphadenopathy and sore throat are not typical for AIH, but elevated IgG levels, positive ANA and SLA are typical serological findings in this condition.5

This patient had been previously treated with clarithromycin, which could cause cholestasis. However, drug toxicity can be ruled out best by a positive diagnosis, which would explain the symptoms of the patient better.

Outcome and follow-up

No liver biopsy was obtained, and no specific therapy was started. After 3 days the patient improved, with a significant drop in bilirubin levels and LFTs (figure 1). The patient was discharged, and outpatient clinical follow-up was scheduled. After 2 weeks, bilirubin levels normalised, with only minimal remaining elevated LFTs. On subsequent testing, HAV serology was negative and a drop in total IgG was noted. Three months after onset of symptoms, the patient fully recovered. Laboratory values for LFTs, bilirubin, IgG, ANA and SLA were within normal limit. Anti-EBNA turned positive confirming the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis with hepatitis in our patient.

Discussion

Infectious mononucleosis is a common clinical condition caused by EBV infection in patients typically 10 to 30 years of age. It is characterised by the triad of fever, tonsillar pharyngitis and lymphadenopathy. It also frequently presents with splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and jaundice.3

EBV is a gamma herpes virus that replicates primarily in the epithelial cells of the pharynx and the salivary glands. After a lytic cycle, EBV spreads to B lymphocytes. Infected B lymphocytes in turn undergo replication and polyclonal activation, leading to an increase of various antibody titres during infectious mononucleosis, with major increases of total IgM and IgG levels.6

This patient presented with an illness compatible with infectious mononucleosis confirmed by serology with positive anti-VCA IgM. Seroconversion to positive anti-EBNA IgM after 3 months effectively proves EBV infection. In contrast, negative anti-HAV IgG 1 month after presentation strongly argues against acute HAV infection. Similarly, normal IgG, ANA and SLA 3 months after onset of symptoms effectively rule out AIH.

The diagnosis in our case was challenging due to false positivity to anti-HAV IgG and IgM as well as elevated IgG, ANA and SLA, suggesting two differential diagnoses also explaining jaundice and at least some of the symptoms of the patient. Since liver involvement is common in EBV infection, acute hepatitis due to EBV can mimic both acute hepatitis A infection and AIH. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion for EBV infection is warranted in cases of acute hepatitis even if other serological investigations are positive. In cases of uncertain diagnosis, serological follow-up is required.

EBV is a B-cell tropic virus, which can promote replication and activation of infected B cells. This results in an increase in IgG and non-specific immune reactions, such as the appearance of heterophile antibodies. Simultaneous presence of anti-VCA EBV IgM and anti-HAV IgM has been previously described.7 Similarly, Fogeda et al described a positive serological test with anti-HEV antibodies in patients with CMV or EBV infection.8 Activation of a varicella zoster virus-specific IgA response during acute EBV infection has also been reported.9 Moreover, EBV and CMV IgM dual positivity in children with primary EBV infection is well described, possibly due to antigenic cross-reactivity.10–12 Even response rates for routine parasite serological tests had been described to be higher in patients with mononucleosis presumably due to heterophile antibodies.13

B-cell activation during EBV infection could benefit the host, although disturbance of this homeostasis can cause serious diseases such as several EBV-associated cancers and autoimmune diseases.14 15

EBV was previously suggested as a potential trigger for autoimmune hepatitis.16–18 In our patient, we found positive ANA titres as well as positivity for SLA, with moderate elevation of IgG. Untreated AIH is an aggressive disease leading to cirrhosis with a mortality of up to 50% within 2–4 years. However, serological markers for AIH were negative during follow-up after 3 months, effectively ruling out AIH. Our literature research did not reveal previous examples of EBV infection mimicking AIH. Elevated IgG levels in EBV infection could lead to misdiagnosis of other autoimmune disorders, for example, IgG4-related disease.19

In summary, testing for EBV infection is warranted in patients presenting with acute hepatitis and the treating physician should carefully evaluate other serological results that may be potentially false positive in infectious mononucleosis. In life-threatening situations, a liver biopsy should be considered to establish the correct diagnosis. In cases that spontaneously resolve, repeat serological testing can help to establish the true diagnosis in retrospect.

Patient’s perspective.

I was very worried about the possible differential diagnoses of an autoimmune hepatitis and very relieved when I received the final diagnosis of Epstein–Barr virus-associated hepatitis later during the follow-up of my blood results.

Learning points.

Infectious mononucleosis frequently presents with splenomegaly, hepatomegaly and jaundice and is therefore an important differential diagnosis in acute hepatitis.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection leads to B-cell activation, resulting in IgG elevation and potentially false-positive serological tests for other conditions including hepatitis A virus and autoimmune hepatitis.

In infectious mononucleosis, positive serological tests should be critically evaluated in light of the clinical presentation. Follow-up tests after resolution of acute EBV infection might clarify ambiguous diagnostic situations.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to patient care, concept and design of the manuscript. MV wrote the first draft, and FT and BM revised the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Rea TD, Russo JE, Katon W, et al. Prospective study of the natural history of infectious mononucleosis caused by Epstein-Barr virus. J Am Board Fam Pract 2001;14:234–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kinderknecht JJ. Infectious mononucleosis and the spleen. Curr Sports Med Rep 2002;1:116–20. 10.1249/00149619-200204000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dunmire SK, Hogquist KA, Balfour HH, et al. Infectious mononucleosis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2015;390(Pt 1):211–40. 10.1007/978-3-319-22822-8_9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cuthbert JA. Hepatitis A: old and new. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001;14:38–58. 10.1128/CMR.14.1.38-58.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2010;51:2193–213. 10.1002/hep.23584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosén A, Gergely P, Jondal M, et al. Polyclonal Ig production after Epstein-Barr virus infection of human lymphocytes in vitro. Nature 1977;267:52–4. 10.1038/267052a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Naveau S, Delfraissy JF, Poitrine A, et al. [Simultaneous detection of IgM antibodies against the hepatitis A virus and the viral capsid antigen of Epstein-Barr virus in acute hepatitis]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1985;9:109–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fogeda M, de Ory F, Avellón A, et al. Differential diagnosis of hepatitis E virus, cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus infection in patients with suspected hepatitis E. J Clin Virol 2009;45:259–61. 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karner W, Bauer G. Activation of a varicella-zoster virus-specific IgA response during acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Med Virol 1994;44:258–62. 10.1002/jmv.1890440308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miendje Deyi Y, Goubau P, Bodéus M. False-positive IgM antibody tests for cytomegalovirus in patients with acute Epstein-Barr virus infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2000;19:557–60. 10.1007/s100960000317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park JM, Shin JI, Lee JS, et al. False positive immunoglobulin m antibody to cytomegalovirus in child with infectious mononucleosis caused by epstein-barr virus infection. Yonsei Med J 2009;50:713–6. 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.5.713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sohn MJ, Cho JM, Moon JS, et al. EBV VCA IgM and cytomegalovirus IgM dual positivity is a false positive finding related to age and hepatic involvement of primary Epstein-Barr virus infection in children. Medicine 2018;97:e12380 10.1097/MD.0000000000012380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kern W, Kirsten C, Förster P, et al. Specificity of routine parasite serological tests in autoimmune disorders, neoplastic disease, EBV-induced mononucleosis, and HIV infection. Klin Wochenschr 1987;65:898–905. 10.1007/BF01745500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor GS, Long HM, Brooks JM, et al. The immunology of Epstein-Barr virus-induced disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2015;33:787–821. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cruz-Muñoz ME, Fuentes-Pananá EM. Beta and Gamma Human Herpesviruses: Agonistic and Antagonistic Interactions with the Host Immune System. Front Microbiol 2017;8:2521 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rigopoulou EI, Smyk DS, Matthews CE, et al. Epstein-barr virus as a trigger of autoimmune liver diseases. Adv Virol 2012;2012:1–12. 10.1155/2012/987471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vento S, Guella L, Mirandola F, et al. Epstein-Barr virus as a trigger for autoimmune hepatitis in susceptible individuals. Lancet 1995;346:608–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91438-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wada Y, Sato C, Tomita K, et al. Possible autoimmune hepatitis induced after chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Clin J Gastroenterol 2014;7:58–61. 10.1007/s12328-013-0438-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wada Y, Kojima M, Yoshita K, et al. A case of Epstein-Barr virus-related lymphadenopathy mimicking the clinical features of IgG4-related disease. Mod Rheumatol 2013;23:597–603. 10.3109/s10165-012-0695-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]