Abstract

We discuss the application of quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) free energy simulations to the analysis of phosphoryl transfers catalyzed by two enzymes: alkaline phosphatase and myosin. We focus on the nature of the transition state and the issue of mechanochemical coupling, respectively, in the two enzymes. The results illustrate unique insights that emerged from the QM/MM simulations, especially concerning the interpretation of experimental data regarding the nature of enzymatic transition states and coupling between global structural transition and catalysis in the active site. We also highlight a number of technical issues worthy of attention when applying QM/MM free energy simulations, and comment on a number of technical and mechanistic issues that require further studies.

1. INTRODUCTION

Phosphoryl transfer represents arguably one of the most important classes of biological transformations (Alberts et al., 1994; Cleland & Hengge, 2006; Kamerlin, Sharma, Prasad, & Warshel, 2013; Knowles, 1980; Lassila, Zalatan, & Herschlag, 2011; Westheimer, 1987). Itis involved in many key biological processes such as bioenergy transduction (e.g., ATP hydrolysis in biomolecular motors), signal transduction (e.g., GTP hydrolysis in G-proteins and phosphorylation/dephosphorylation by kinases/phosphatases), and genome processing (e.g., DNA/RNA synthesis in DNA/RNA polymerases); there are ~2000 protein kinases and ~1000 phosphatases in the human genome. Therefore, disruption or impairment of phosphoryl-transfer reaction may significantly perturb the function of the proteins involved and lead to serious diseases such as cancer (Campisi & di Fagagna, 2007; Kiaris & Spandidos, 1995; Lange, Takata, & Wood, 2011; Roberts & Der, 2007; Shaw & Cantley, 2006). Indeed, protein kinases and phosphatases are among the most important drug targets (Cohen, 2002; Collins & Workman, 2006; Davies, Reddy, Caivano, & Cohen, 2000; Garber, 2001; Robertson, 2007; Schwartz & Murray, 2009; Zhang, 2002).

Motivated by such considerations, extensive efforts have been paid to studying the mechanism of phosphoryl-transfer reactions in both small molecules and proteins in the past few decades. These investigations have targeted both the underlying chemical processes (e.g., whether the reaction involves any intermediate and the nature of the transition state) and strategies that proteins employ to regulate the rate of phosphoryl transfers. In an excellent review article, rather up to date findings from extensive experimental studies, especially concerning the chemical mechanism of biological phosphoryl transfers and nature of transition state, were summarized (Lassila et al., 2011). In recent years, as computational hardware and methodologies continue to improve, computational studies have become increasingly effective at analyzing the mechanism of reaction mechanisms in biomolecules. Specifically for phosphoryl-transfer reactions, hybrid quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) type of computations (Brunk & Rothlisberger, 2015; Friesner & Guallar, 2005; Garcia-Viloca, Gao, Karplus, & Truhlar, 2004; Hu & Yang, 2008; Kamerlin, Haranczyk, & Warshel, 2009; Monard & Merz, 1999; Riccardi et al., 2006; Senn & Thiel, 2009) has been used by several research groups (Åqvist & Kamerlin, 2016; Carvalho, Szeler, Vavitsas, Åqvist, & Kamerlin, 2015; Duarte, Amrein, & Kamerlin, 2013; Genna, Vidossich, Ippoliti, Carloni, & De Vivo, 2016; Grigorenko et al., 2007; Hayashi et al., 2012; Hou & Cui, 2012, 2013; Kamerlin et al., 2013; Kiani & Fischer, 2014, 2016; McCullagh, Saunders, & Voth, 2014; McGrath, Kuo, Hayashi, & Takada, 2013; Mlynsky et al., 2014; Pabis, Duarte, & Kamerlin, 2016; Rosta, Kamerlin, & Warshel, 2008; Roston & Cui, 2016a, 2016b; Roston, Demapan, & Cui, 2016) to provide mechanistic insights into a broad set of enzymes that catalyze different phosphoryl transfers. These studies underlined subtleties in the interpretation of experimental data, which include both “direct” observations such as crystal structures and “indirect” observables such as kinetic isotope effects (KIEs), activation entropy, and (linear) free energy relationships.

In this contribution, we discuss our recent studies of phosphoryl transfers catalyzed by several enzymes using QM/MM methodologies developed in our group. In addition to highlighting the unique contribution of these QM/MM studies to the understanding of detailed catalytic mechanism, another aim is to summarize our QM/MM methodologies regarding both strength and remaining limitations. We also comment on future development and application of computational studies targeting biological phosphoryl transfers.

2. BACKGROUND ON COMPUTATIONAL METHODS

Enzymes feature motions that span a broad range of temporal and spatial scales. Identifying which motions make an essential contribution to the chemical reaction that an enzyme catalyzes remains a major challenge in the field of enzymology (Nashine, Hammes-Schiffer, & Benkovic, 2010). In principle, all motions that occur at a time scale faster than the chemical reaction, which for natural enzymes is commonly in the range of milliseconds, should be properly averaged to define the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of the catalyzed reaction (Cui & Karplus, 2003; Zhou, 2010). In practice, it remains a major challenge to conduct an adequate canonical average over the configurations implicated in these motions with either direct or enhanced sampling methods. Meeting this challenge is particularly important to the study of phosphoryl transfers as many relevant enzymes are known to be particularly flexible and therefore rich in μs–ms motions. Our general aim, therefore, is to develop QM/MM methods that are able to reach the μs time scale in the near future using modest computational resources, while maintaining a level of accuracy adequate for addressing the relevant mechanistic questions.

2.1. QM/MM Potential Function

Two levels of QM/MM potential functions are used in our studies. The semiempirical type (Christensen, Kubar, Cui, & Elstner, 2016; Thiel, 1996) of QM/MM methods is computationally efficient and thus can be used in direct molecular dynamics and free energy simulations (Gao et al., 2006; Pu, Gao, & Truhlar, 2006; Riccardi et al., 2006). QM/MM methods based on ab initio or density functional theory (DFT) (Brunk & Rothlisberger, 2015; Hu & Yang, 2008) are much more expensive (about a factor of 103 or more) and therefore are used in either minimization or free energy path type of calculations (see Section 2.2). Because the coupling between QM and MM atoms and subtleties associated with the QM/MM partitioning have been well described in previous work (Gao, Amara, Alhambra, & Field, 1998; König, Hoffmann, Frauenheim, & Cui, 2005; Reuter, Dejaegere, Maigret, & Karplus, 2000; Senn & Thiel, 2009), we focus here on the discussion of the QM potential (Cui, 2016). The proper size of the QM region in QM/MM simulations of enzymes has been an interesting subject of discussion and debate in the recent literature (Flaig, Beer, & Ochsenfeld, 2012; Hu, Soderhjelm, & Ryde, 2011; Jindal & Warshel, 2016; Kulik, Zhang, Klinman, & Martinez, 2016); in our own experience, provided that the QM/MM boundary is carefully treated (König et al., 2005; Reuter et al., 2000; Roston & Cui, 2016a), a QM region involving 100–150 atoms is often adequate for many mechanistic analyses, especially when sampling is properly done to allow adequate response of the MM region to charge redistribution of the QM region during the chemical reaction (Riccardi et al., 2006).

2.1.1. Semiempirical QM/MM Methods

There are two popular types of semiempirical QM models: the more traditional neglect of diatomic differential overlap (NDDO) methods (Thiel, 1996) such as AM1, PM3, and the more recent OM2/3 models (Dral, Wu, Sporkel, Koslowski, & Thiel, 2016), and the density functional tight binding model (DFTB) (Elstner et al., 1998; Gaus, Cui, & Elstner, 2014). With the use of a minimal basis and approximations of integrals (or Hamiltonian matrix elements), these methods are computationally efficient and are 2–3 orders of magnitude faster than ab initio or DFT calculations. Therefore, these methods can be routinely used in direct MD-based simulations at the 10–100 ns scale, with a QM region of about <200 atoms. For larger QM regions, linear-scaling methods have been developed (Liu et al., 2001; Nishizawa, Nishimura, Kobayashi, Irle, & Nakai, 2016) although the application to realistic enzyme systems has been limited, due in part to the limited accuracy of semiempirical methods for noncovalent interactions in biomolecules, as compared to well-parameterized classical force fields; as discussed in Christensen et al. (2016), systematic improvement of semiempirical methods for biomolecular structure and interaction is an important area of research.

Specifically in the context of phosphoryl-transfer reactions, both NDDO type of method (AM1-d) (Nam, Cui, Gao, & York, 2007) and the third-order variant of DFTB (DFTB3 (Gaus, Cui, & Elstner, 2011)) have been specifically adjusted for describing phosphoryl-transfer reactions (Gaus, Lu, Elstner, & Cui, 2014). The fact that specific parameterizations are required suggests that approximations in both methods make them less robust for describing the complexity of the underlying potential energy surfaces for phosphoryl transfers (Florian & Warshel, 1998). This is not due to the strong participation of d orbitals, as both AM1-d and DFTB3 explicitly include d orbitals in the basis set and a natural bonding orbital (NBO (Reed, Curtiss, & Weinhold, 1988; Weinhold & Landis, 2005)) analysis of relevant structures reveals that the participation of the d orbitals is very limited (Table 1) at both DFTB3 and DFT levels. Identifying the origins for the limited transferability of current semiempirical methods for phosphoryl-transfer reactions is of major interest (Mlynsky et al., 2014). For specific applications, it is always important to test the semiempirical method using active-site model systems against high-level QM methods, as we show in Section 2.1.2 using alkaline phosphatase (AP) as an example.

Table 1.

Natural Bonding Orbitals for P–O Bonds in a Protonated Dimethyl Phosphate From DFTB3/3OB and B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ Calculations

| DFTB3 | B3LYP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bond | P | O | P | O |

| P–O1 | 0.53 sp3.41d0.02 | 0.85 sp3.22 | 0.47 sp3.34d0.10 | 0.88 sp2.47 |

| P–O2 | 0.60 sp2.14d0.00 | 0.80 sp2.94 | 0.51 sp2.07d0.04 | 0.86 sp2.18 |

| P–O3 | 0.54 sp3.28d0.02 | 0.84 sp2.81 | 0.47 sp3.29d0.10 | 0.89 sp2.60 |

| P–O4 | 0.54 sp3.47d0.02 | 0.84 sp3.17 | 0.46 sp3.31d0.11 | 0.89 sp2.79 |

Another major issue for applying semiempirical methods to phosphoryl-transfer systems is the treatment of metal ions, which are often featured in the active site of the relevant enzymes. Currently available NDDO methods are usually not sufficiently reliable for metal ions, especially transition-metal ions. DFTB, which is based on DFT rather than Hartree–Fock, appears more promising for the description of metal ions; specifically for DFTB3, parameterization has been done for several main group ions such as Na+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ (Kubillus, Kubař, Gaus, Řezáč, & Elstner, 2015; Lu, Gaus, Elstner, & Cui, 2015), as well as for simpler transition-metal ions such as Zn2+ (Lu et al., 2015) and Cu+/2+ (Gaus et al., 2015). The performance of DFTB3 is most impressive for structural properties of metal compounds, while the energetics are less accurate, especially for highly charged ligands, due presumably to the limited description of polarization and charge-transfer effects. Even with the current set of parameters, nevertheless, DFTB models have been shown to be highly effective for the description of ligand binding to zinc-enzymes (Pecina et al., 2017); systematic improvement of DFTB models for more complex transition-metal ions remains a topic of major interest.

2.1.2. Ab Initio and DFT QM/MM Methods

Ab initio and DFT methods are generally more robust than semiempirical methods. Due to computational cost, DFT methods are often chosen in QM/MM calculations for enzymes, although energies can be further corrected based on higher-level methods, including QM/QM′ embedding methods in which the central region is described with a highly correlated QM method such as CCSD(T) (Claeyssens et al., 2006), while the rest of the QM atoms are described with DFT (Bennie et al., 2016; Manby, Stella, Goodpaster, & Miller, 2012). When transition-metal ions are involved, doing such a local correction is worthwhile as it is not straightforward to identify the most reliable density functional for the metal center of interest (Cramer & Truhlar, 2009; Jiang, Laury, Powell, & Wilson, 2012).

Another issue of concern is the contribution from long-range dispersion interactions, which are missing in most popular GGA-based DFT methods (Grimme, Hansen, Brandenburg, & Bannwarth, 2016); for large QM regions, long-range dispersion can be important and neglect of the contribution can affect both the structure (a comparison is made in Table 2) and the reaction energetics (see Table 3 as an example). Fortunately, empirical dispersion models have been developed for both DFT (Grimme et al., 2016) and semiempirical models (Brandenburg, Hochheim, Bredow, & Grimme, 2014; Elstner, Hobza, Frauenheim, Suhai, & Kaxiras, 2001; Tuttle & Thiel, 2008) and they appear to be effective in many practical applications.

Table 2.

Key Structural Parameters (in Å) in an Active-Site Model of AP in the Gas Phase (see Fig. 1) From DFTB3 and B3LYP Calculations

| B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) | DFTB3/3OB | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Onuc⋯P | P⋯Olg | δ | Onuc⋯P | P⋯Olg | δ |

| MpNPP− | 2.22 | 1.99 | +0.23 | 2.21 | 1.91 | +0.30 |

| MmNPP− | 2.08 | 1.96 | +0.12 | 2.14 | 1.86 | +0.28 |

| MPP− | 1.99 | 2.06 | −0.07 | 1.86 | 2.14 | −0.28 |

Diester phosphate substrates are studied. MpNPP, methyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate; MmNPP, methyl m-nitrophenyl phosphate; MPP, methyl phenyl phosphate. “δ” is the difference between the breaking (P ⋯ Olg and forming (Onu⋯P) bonds.

Table 3.

Calculated Activation Barrier (in kcal/mol) for Diester Hydrolysis in the Active-Site Model of AP in the Gas Phase (see Fig. 1)

| Single Points at DFTB3 Geometries |

Single Points at B3LYP Geometries |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | DFTB3 | B3LYP | M06 | MP2 | B3LYP | M06 | MP2 |

| MpNPP− | 8.8 | 9.2 (4.2a) 5.7 (3.1) | 7.6 | 12.0 (6.7) | 6.8 (6.1) | 8.8 | |

| MmNPP− | 9.7 | 9.2 (9.4) | 6.8 (7.5) | 13.6 | 15.3 (12.0) | 13.2 (12.8) | 13.2 |

| MPP− | 20.0 | 16.2 (9.1) | 11.6 (7.1) | 9.6 | 20.1 (11.6) | 13.0 (10.8) | 10.4 |

The number with parentheses is obtained with corresponding DFT functional plus D3 dispersion. The geometries are optimized either at DFTB3/3OB or B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level. Single point energy calculations are carried out at B3LYP, M06, and MP2 method at two levels of geometries using a larger basis set of 6-311++G(d,p).

2.2. Free Energy Computations With QM/MM Potentials

The topic of free energy simulations has been covered in many recent review articles (Barducci, Bonomi, & Parrinello, 2011; Pohorille, Jarzynski, & Chipot, 2010), including that focus on QM/MM potential functions (Brunk & Rothlisberger, 2015; Kamerlin et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2016). Below, we touch on a few points particularly relevant to the study of biological phosphoryl-transfer reactions.

2.2.1. Direct Sampling: Metadynamics and String Methods

With semiempirical QM/MM potentials, it is feasible to conduct direct sampling of the free energy surface using techniques such as umbrella sampling (Torrie & Valleau, 1977), metadynamics (Barducci et al., 2011), and string methods (Weinan & Vanden-Eijnden, 2010). One specific feature associated with phosphoryl transfers is that multiple reaction pathways are likely available and relatively similar in free energy profiles (Florian & Warshel, 1998; Yang & Cui, 2009). For example, the competition between dissociative and associative mechanisms, which differ in terms of whether a pentavalent intermediate exists or not, remains debated in several key enzymes (Lassila et al., 2011); moreover, as discussed in Section 3.2 using myosin as an example, multiple water molecules and/or protein sidechains might be involved in mediating proton transfers during the phosphoryl-transfer reaction. Therefore, care has to be exercised to select reaction coordinates (or referred to as collective variables) that drive the free energy simulations; inappropriate choice of reaction coordinates projects configurations of distinct chemical structures into the same region on the reduced conformational space, thus leading to a less physically meaningful free energy surface.

The string suite of methods has become popular in recent years and has been applied to enzymatic reactions (Rosta, Nowotny, Yang, & Hummer, 2011); these methods represent the reaction pathway with a string in a reduced space spanned also by a set of collective variables. Because the string is a one-dimensional quantity, the number of collective variables used in such calculations can be substantially larger than in metadynamics simulations, which aim to construct a multidimensional free energy surface. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that there are multiple variants of the string method, which treat thermal fluctuations in different ways with different underlying approximations (Maragliano, Fischer, Vanden-Eijnden, & Ciccotti, 2006). For example, in the variant of the string method applied to the myosin example (Lu, Ovchinnikov, Roston, Demapan, & Cui, 2017) in Section 3.2, the entropic contribution associated with thermal fluctuations of the collective variables is treated approximately compared to the finite temperature string approach (Maragliano et al., 2006; Ovchinnikov, Karplus, & Vanden-Eijnden, 2011); therefore, the number of collective variables used to parameterize the string should be carefully selected. Moreover, in both metadynamics and string calculations, there are a number of key parameters that influence the convergence and accuracy of these calculations; an example in the string calculations is the force constant used to control the degree of sampling orthogonal to the path, which determines the accuracy of the mean force (Lu et al., 2016); another issue is the overlap of the configurations sampled along the string, and conducting Hamiltonian replica exchange is useful in this regard (Rosta et al., 2011). Therefore, it is important to recognize that these methods are not entirely “black boxes” and the key parameters need to be chosen carefully based on test calculations.

2.2.2. Minimum Free Energy Path Approach for Ab Initio QM/MM

With ab initio/DFT-based QM/MM potentials, it is usually too expensive to conduct sufficient sampling for biological applications. The most practical approach is the minimum free energy path (MFEP) method pioneered by Hu and Yang (2008), in which the fluctuations of the QM and MM atoms are decoupled; the MFEP is then defined as the steepest descent path on the potential of mean force for the QM atoms that connects the reactant and product basins. Similar to the variant of the string approach applied below to myosin, the thermal fluctuations of the QM atoms orthogonal to the MFEP are treated approximately and estimated using a harmonic model. Moreover, to compute the mean force on the QM atoms in a cost–effective manner, the MM degrees of freedom are sampled using MD simulations in which the QM atoms are replaced with a set of classical atoms whose charge distribution is determined using a mean-field model. Using a small phosphate molecule in solution, we found (Lu et al., 2016) that the mean-field approximation leads to an adequate estimate of the mean force with errors on the order of 0.5–1 kcal/mol Å−1; a reweighting scheme has been proposed in the literature (Hayashi et al., 2017; Kosugi & Hayashi, 2012) and might reduce the magnitude of the error. For biomolecular applications, one potential concern is that the QM degrees of freedom are treated with minimization in the MFEP search, thus large amplitude motions of the QM atoms (e.g., rearrangement of water molecules, see discussion of myosin, or change of hydration (Liang, Swanson, Peng, Wikström, & Voth, 2016; Lu et al., 2016)) during the reaction might be missed. Therefore, for complex chemical transformations, it is beneficial to compare results from the MFEP approach and direct free energy simulations using an inexpensive QM/MM potential; once subtleties associated with sampling for the specific system in hand are better understood, the energetics can be further improved by either MFEP calculations using a high-level QM/MM potential, or other multilevel free energy approaches discussed in the next section.

2.2.3. Multilevel QM/MM Free Energy Calculations

The importance of integrating different levels of QM/MM simulations can be highlighted using the example of proton transfer in human carbonic anhydrase (CAII), a well-studied system both experimentally (Silverman & McKenna, 2007) and computationally (Maupin, McKenna, Silverman, & Voth, 2009; Riccardi, Yang, & Cui, 2010). With extensive DFTB/MM free energy simulations using a collective variable that describes the translocation of the excess proton, we found that the reaction proceeds through a set of stepwise proton transfers (Riccardi, Koenig, Guo, & Cui, 2008); this aspect of the reaction was also observed in MS-EVB-based free energy simulations (Maupin et al., 2009). Using a B3LYP/MM potential and MFEP, however, the transition state was observed to be highly concerted in nature (see Fig. 2). Evidently, it is worth further exploring strategies that integrate extensive sampling and higher accuracy, which are offered by semiempirical and ab initio/DFT QM/MM methods, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Optimized structures for the reactant (A), transition state (B), and product (C) for the proton transfer in human carbonic anhydrase using the B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p)//CHARMM MFEP approach;the computed free energy profile is shown in (D). The QM region includes the zinc ions, its ligands, His 64 (proton acceptor), and the two bridging water molecules.

One strategy in this context is multilevel QM/MM free energy simulations, in which the reaction pathway is explored at the low-level (e.g., semiempirical QM/MM) with umbrella sampling or the string method; then the relative free energies of key stationary points (e.g., transition state and reactant/product) are improved by conducting high-level QM/MM calculations (Marti, Moliner, & Tuñón, 2005; Polyak, Benighaus, Boulanger, & Thiel, 2013). The simplest “correction” is to compute the potential energy difference between low- and high-level QM/MM potentials along the minimum energy path, although it is difficult to evaluate whether such a correction remains transferable as thermal fluctuations of the system are taken into consideration. To evaluate the free energy difference between different levels of QM/MM potentials, it is necessary to conduct MD sampling for the relevant stationary points (e.g., by constraining the value of the reaction coordinate to specific values). The degree of sampling required for such a free energy perturbation to reach reasonable convergence depends on the distribution overlap between the two levels of QM/MM potentials (Boresch & Woodcock, 2017; Lu et al., 2016). In practice, it is likely that some degree of sampling at the high QM/MM level is required (König, Hudson, Boresch, & Woodcock, 2014; Lu et al., 2016; Plotnikov, Kamerlin, & Warshel, 2011), although innovative strategies [e.g., machine learning (Shen, Wu, & Yang, 2016)] may be required to minimize the computational cost; this remains an active area of research.

2.3. Other Experimental Observables

In addition to the activation free energy barrier, other experimental observables should be computed to allow a systematic comparison to experiments; considering the various approximations in computational methods, agreement with experimental activation free energy alone does not provide a compelling support for the computational model. These include, for example, various spectroscopic data such as infrared, Raman and nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts, free energy relationships, and KIEs. For the computation of these experimental observables, QM/MM models are uniquely useful as compared to reactive force field models, such as MS-EVB; while it is possible to parameterize VB type of models for energetics, it is generally difficult to parameterize such models for other properties such as variation of vibrational frequency and charge along the reaction pathway. As computational hardware and methodologies continue to improve, QM/MM calculations for these experimental observables can be conducted for increasingly realistic enzyme models with less approximation. For example, although KIEs were largely computed using models based on (generalized) normal mode analysis (Gao & Truhlar, 2002), it has become feasible to conduct path integral simulations that treat nuclear quantum effects beyond the harmonic model (Major & Gao, 2007; Wang, Ceriotti, & Markland, 2014). As discussed in Section 3.1 using AP as an example, QM/MM calculations can help highlight subtleties associated with the interpretation of various experimental observables.

3. CASE STUDIES

In this section, using two enzymes that we have studied in recent work, we illustrate the application of various QM/MM approaches to the analysis of phosphoryl-transfer mechanisms.

3.1. Alkaline Phosphatase: Phosphoryl-Transfer Transition State

AP has attracted much attention in recent years in the area of enzymology because it is one of the remarkable examples of catalytic promiscuity (Jonas & Hollfelder, 2009; O’Brien & Herschlag, 1999a; Pabis et al., 2016): it catalyzes the hydrolysis of phosphate monoesters with an impressive proficiency of 1027, but it is also able to catalyze the hydrolysis of phosphate diesters, triesters, and sulfate monoesters with respectable efficiency as well. Such a level of promiscuity makes it possible to study the catalysis with a broad range of substrates, providing fairly unique data, such as free energy relationships (Nikolic-Hughes, Rees, & Herschlag, 2004; Zalatan & Herschlag, 2006), that shed light onto the nature of the phosphoryl-transfer transition state and factors that dictate the catalytic efficiency and selectivity. The large body of diverse experimental data (Andrews, Deng, & Herschlag, 2011; Andrews, Fenn, & Herschlag, 2013; Bobyr et al., 2011, 2012; Catrina et al., 2007; Lassila & Herschlag, 2008; Nikolic-Hughes, O’Brien, & Herschlag, 2005; Nikolic-Hughes et al., 2004; O’Brien & Herschlag, 1998, 1999b, 2001, 2002; O’Brien, Lassila, Fenn, Zalatan, & Herschlag, 2008; Peck, Sunden, Andrews, Pande, & Herschlag, 2016; Sunden, Peck, Salzman, Ressl, & Herschlag, 2015; Zalatan et al., 2007; Zalatan, Fenn, Brunger, & Herschlag, 2006; Zalatan, Fenn, & Herschlag, 2008; Zalatan & Herschlag, 2006) also provides an opportunity to test computational methods as well as popular models used for interpreting experimental data.

3.1.1. Nature of Transition State and Free Energy Relationships

Free energy relationships are widely used in the physical organic literature (Greig, 2010; Williams, 2003) (also see Florian, Aqvist, & Warshel, 1998; Rosta et al., 2008). For the phosphoryl-transfer reaction in AP, the nucleophile is a protein residue, Ser102 (see Fig. 3). The free energy relationships were thus evaluated with different substrate leaving groups for a series of phosphate monoesters and diesters (Zalatan & Herschlag, 2006); for the cognate substrate phosphate monoesters, the measurements were done with the R166S variant to ensure that the chemical step is rate limiting. The Brönsted slope βlg^ was measured to be −0.85 ± 0.13 and −0.95 ± 0.08 for the monoesters (O’Brien & Herschlag, 2002) and diesters (Zalatan & Herschlag, 2006), respectively; these are similar in magnitude (following the consideration of binding contribution to the observed βlg (O’Brien & Herschlag, 2002)) to the values measured in solution, −1.23 and −0.94 ± 0.05, for aryl monoesters and diesters, respectively (Lassila et al., 2011; Zalatan & Herschlag, 2006). Therefore, the interpretation (Zalatan & Herschlag, 2006) was that the phosphoryl-transfer transition state in AP resembles that in solution, which has been established to be loose and synchronous in nature for monoesters and diesters, respectively (Lassila et al., 2011). In other words, in contrast to the traditional picture of enzyme catalysis, the AP active site appears to be able to stabilize different types of transition states, despite the substantially different charge distributions expected for these transition states.

Fig. 3.

A schematic illustration for the active site of alkaline phosphatase;this also illustrates the minimal QM region used in QM/MM simulations (Roston & Cui, 2016b; Roston et al., 2016).

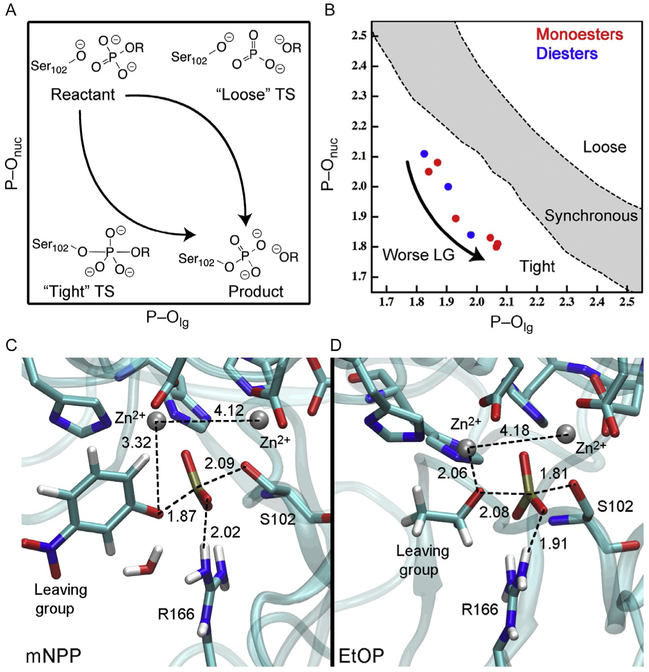

In a loose transition state, there is substantial bond cleavage of the P–Olg bond and little bond formation with the nucleophile; as a result, the formal charge associated with the PO3 moiety is expected to be lower in the transition state as compared to the reactant state (Fig. 4A). In the canonical model for the phosphoryl-transfer transition state in AP (Nikolic-Hughes et al., 2005, 2004; Zalatan et al., 2008), the PO3 moiety interacts with several cationic species in the active site: two zinc ions and the highly conserved Arg166. Thus, the reduction of the formal charge of PO3 would imply that Arg166 is, in fact, “anticatalytic” in the chemical step. This rather unexpected inference suggests that the nature of the transition state in AP deserves further scrutiny; either the electronic structure or the binding mode of the reactive moieties, or both, deviate from the canonical model that emerged from experimental studies.

Fig. 4.

Results from DFTB3/MM simulations for AP with multiple substrates. (A) Formal charges associated with the reaction pathways that involve a loose and tight transition state, respectively. (B) Values for the P–Onuc and P–Olg distances in the transition state computed for a series of mono- and diester phosphate substrates; the boundary between “tight,” “synchronous,” and “loose” transition states is defined approximately based on bond-order considerations (Roston et al., 2016); (C) and (D) Snapshots for the transition state from simulations for phosphate monoesters with a good (m-NP) and a poor (EtO) leaving group, respectively.

Motivated by these considerations, we have conducted QM/MM free energy simulations (Roston et al., 2016) for a series of monoesters and diesters in wild-type AP using the latest formulation of the DFTB model (DFTB3 (Gaus et al., 2011)/3OB (Gaus, Goez, & Elstner, 2012; Gaus, Lu, et al., 2014)); the computational efficiency of the DFTB3 model was essential to the extensive sampling required for the AP system, where catalytic promiscuity stems in part from the open nature of the active site, which is highly accessible to solvent molecules (Hou & Cui, 2013). For each substrate, adaptive umbrella sampling simulations were conducted to construct the two-dimensional free energy surface for the phosphoryl-transfer reaction; the natural reaction coordinates are the breaking and forming P–O bonds associated with the leaving group and nucleophile (Ser102). The QM region contains approximately 125 atoms (Fig. 3) and the free energy simulations include more than 10 ns of sampling for each substrate.

Several features from the QM/MM free energy simulations are worth noting. First, for the series of monoesters studied, the nature of the transition state is tight as reflected by a significant degree of bond formation with the nucleophile (Fig. 4B). As a result, partial charges on the PO3 moiety (Mulliken charge and NBO charge analyses led to similar trends) are more negative in the transition state than in the reactant state (Roston et al., 2016); this trend supports the catalytic role of the conserved Arg166. Second, the degree of bond cleavage in the transition state depends on the nature of the leaving group (Roston et al., 2016); the Wiberg bond order changes from ~0.7 for a decent leaving group (meta-nitrophenyl, mNP) to ~0.4 for a poor leaving group (ethyl oxide). In other words, there is a significant shift in the nature of the phosphoryl-transfer transition state as a function of the leaving group, which suggests that the free energy relationships for the leaving group should contain a significant degree of curvature; a close examination of the experimental data reported in previous literature (Zalatan & Herschlag, 2006) indeed indicates notable deviation from linearity for both phosphate monoesters and diesters. Interpretation of the free energy relationships data without considering the curvature would conclude that the transition state features significant bond cleavage, which is supported by our calculations only for the poor leaving groups. Third, the binding mode of the reactive moieties in the transition state also varies with the leaving group (Fig. 4C and D). For a decent leaving group such as mNP, as there is little charge development on the leaving group in the transition state, the mNP-O fragment does not interact strongly with the active-site zinc ions and is stabilized largely by solvent molecules; the PO3 also interacts only with one zinc ion. For a poor leaving group such as ethyl oxide, which features significant bond cleavage in the transition state, the EtO− fragment is bound to the zinc ion and the PO3 is coordinated with both zinc ions, similar to the canonical model adopted in the experimental literature (Nikolic-Hughes et al., 2005, 2004; Zalatan et al., 2008).

Therefore, the computational studies point to a model in which the bonding nature and binding mode of the transition state vary significantly depending on the leaving group; for additional discussion of tests and predictions of the model, see the original publication (Roston et al., 2016). It should be pointed out that the possibility of transition-state variation with respect to perturbation has been recognized in the literature (Greig, 2010; Williams, 2003); e.g., it was stated that “in principle,” all free energy relationships should be curved. In practice, however, it is usually assumed that deviation from linearity is insignificant (Jencks, 1985) and thus curvature is taken as evidence for a change in the rate limiting step or a change in mechanism. Our analysis for AP suggests otherwise and highlights that experiments that rely on systematic perturbations, either through mutation or change of substrate, should be interpreted with care, as perturbations may lead to nontrivial changes in the properties of interest (e.g., nature of the transition state in the WT enzyme).

Another implication of the computational results, as emphasized in a recent study (Roston & Cui, 2016a), is that crystal structures with transition-state analogs may not accurately reflect the structure and binding mode of the transition state. For AP, for example, crystal structures with vanadate (Bobyr et al., 2011) and tungstate (Peck et al., 2016) suggested a binding mode that appears to be a better representation of the transition state for a substrate with a poor leaving group, in which the PO3 is coordinately simultaneously with the two zinc ions and Arg166.

3.1.2. Nature of Transition State and Kinetic Isotope Effects

KIE measurement is a powerful tool for interrogating the properties of the transition state (Cleland & Hengge, 2006). Over the years, a set of empirical rules have been established for the interpretation of KIEs. For phosphoryl-transfer transitions states (Hengge, 2002), for example, a loose transition state is usually associated with a large and normal 18O KIE for the bridging oxygen and an inverse 18O KIE for the nonbridging oxygens. Although tremendously valuable, these empirical rules were established by considering the contributions from a very limited number of vibrational modes that involve the substituted isotopes. In the enzyme active site, the reactive fragment is bound with multiple interactions, thus many “vibrational modes” might be perturbed due to an isotope substitution and therefore complicate the interpretation of KIEs. Another important issue is that the measurements are on V/K, which includes the binding step.

For AP, KIE measurements for two phosphate monoesters led to results that were not simple to interpret (Zalatan et al., 2007). In the WT enzyme, an aryl leaving group (para-nitrophenyl, pNP) leads to a normal but very small 18O KIE (1.0003) for the bridging oxygen and an inverse nonbridging KIE; in the R166S variant, where the chemical step is fully rate limiting, the bridging oxygen KIE is slightly larger (1.0091). With an alkyl leaving group (m-nitrobenzyl, mNB), the bridging oxygen KIE is substantially larger in both the WT (1.0072) and R166S variant (1.0199). Those results were interpreted (Zalatan et al., 2007) to suggest that the transition state is loose for both substrates, although the magnitude of bridging oxygen KIE is reduced due to strong interactions with the active site; the larger bridging oxygen KIEs for the alkyl leaving group were thought to arise from the intrinsically larger KIEs for alkyl phosphates than aryl phosphates, even with the same degree of P–Olg cleavage.

The computational efficiency of the DFTB3/MM approach allowed us to compute the 18O KIEs (Roston & Cui, 2016b) with both the bridging and nonbridging oxygen substitutions using a path-integral-based free energy perturbation approach (Major & Gao, 2007). The calculation assumes that the location of the transition state does not vary due to isotope substitution, while the vibrational contribution to the free energy is evaluated with anharmonicity included. The results led to several interesting observations. First, the QM/MM KIE results generally captured the trends observed in the experimental measurements; i.e., a normal bridging oxygen KIE and an inverse nonbridging oxygen KIE, and that alkyl leaving groups have larger bridging oxygen KIEs than aryl leaving groups. Therefore, the KIE results generally support the qualitative trends in the computed transition-state structures for the set of substrates studied. Second, comparison of computed equilibrium and KIEs indicated that the origin of the difference between aryl and alkyl leaving groups was not the intrinsic difference between the corresponding substrates, but rather due to the different degrees of bond cleavage in the transition state, further supporting our model that the nature of the transition state varies with different leaving groups. Third, with an active-site model, DFTB3 and B3LYP calculations give consistent results but they do not capture the experimental trends. This observation highlights the importance of explicitly including the enzyme contribution and that interactions with the enzyme environment may make substantial contributions to KIEs. In fact, path integral calculations found rather significant binding isotope effects for the bridging oxygen in the ground state, suggesting that the substrate structure is deformed toward the transition state upon binding to the enzyme active site. For additional discussion, see Roston and Cui (2016b).

3.1.3. Remaining Questions and Methodological Challenges

Taken together, the DFTB3/MM free energy and KIE calculations led to a different model for the phosphoryl-transfer reaction in AP as compared to previous experimental studies. Although the model appears consistent with experimental data published to date, and it led to a number of testable predictions explicitly summarized in Roston et al. (2016), we note that several features of AP catalysis remain to be better understood.

First of all, while the DFTB3/MM simulations thoroughly explored the free energy surface near the transition-state region, the calculations were not able to reliably predict the activation free energy. As the substrate moves further away from the nucleophile, solvent molecules penetrate into the active site; as a result, the free energy surface for the reactant region was found to be too broad to allow a clear definition of the Michaelis complex, making it difficult to reliably evaluate the activation free energy and therefore an explicit evaluation of the free energy relationships. Although the substrate is expected to bind weakly to the active site due to its solvent accessible nature, the difficulty in defining the Michaelis complex in the simulations highlights the importance of balancing QM-QM and QM/MM interactions at the enzyme/solvent interface (Roston & Cui, 2016a). Further improvement of DFTB3 and DFTB3/MM for noncovalent interactions is clearly warranted (Goyal et al., 2014).

Second, recent experimental studies in the Herschlag lab identified nonadditive contributions from residues in the active site (Sunden et al., 2015). It was argued that understanding such cooperative interactions is important for defining features that dictate the catalytic proficiency and selectivity of enzymes. While several cooperative interactions are straightforward to rationalize due to the spatial proximity of the relevant residues, the underlying mechanism for other nonadditive effects requires further explanation. Along this line, QM/MM simulations are expected to make useful contributions, although the issue with defining the Michaelis complex needs to be resolved first.

Finally, although trends in the DFTB3/MM free energy and KIE calculations are robust for both mono- and diester substrates, it is worth evaluating the transition-state properties using ab initio/DFT-based QM/MM simulations. As indicated by the active-site model comparison mentioned in Section 2.1.2, for example, while DFTB3 captures the key trends in DFT calculations (also see Roston & Cui, 2016b), it appears to overestimate the dependence of transition-state geometries on the nature of the leaving group (Table 2); moreover, because the QM region is fairly large (125–250 atoms), dispersion interactions likely make a notable contribution, as hinted by the difference between DFT and MP2 results for the active-site models (Table 3).

3.2. Myosin: Regulation of the Timing of ATP Hydrolysis

ATP and GTP hydrolysis reactions power many biomolecular machines in cells. Although it has become increasingly clear that the remarkable structural transitions in those systems are usually driven by nucleotide binding or dissociation rather than the chemical (hydrolysis) step per se (Gao & Karplus, 2004; Vale & Milligan, 2000; Yu, Ma, Yang, & Cui, 2007), the question of what controls the timing of the hydrolysis step remains relevant; if hydrolysis could occur independent of large structural transitions, the efficiency of energy transduction would be compromised. In this context, there are two possible models: in one model, hydrolysis of nucleotides is strictly controlled by the nearby residues, and conformational transition of the active site is strongly coupled with global structural transitions; i.e., global structural changes are the consequence of active-site events. In the other model, global structural changes explicitly impact the efficiency of ATP hydrolysis, presumably by influencing the structural and dynamical properties of the active site; i.e., global structural changes are the cause of active-site events. The goals of our work are to establish which model is applicable to realistic biomolecular motors and to reveal the underlying molecular mechanism. We choose to focus on the molecular motor myosin due to the rich experimental background in terms of both structural studies and biochemical/kinetic analysis (Geeves & Holmes, 2005; Sweeney & Houdusse, 2010).

3.2.1. Multiple Reaction Pathways

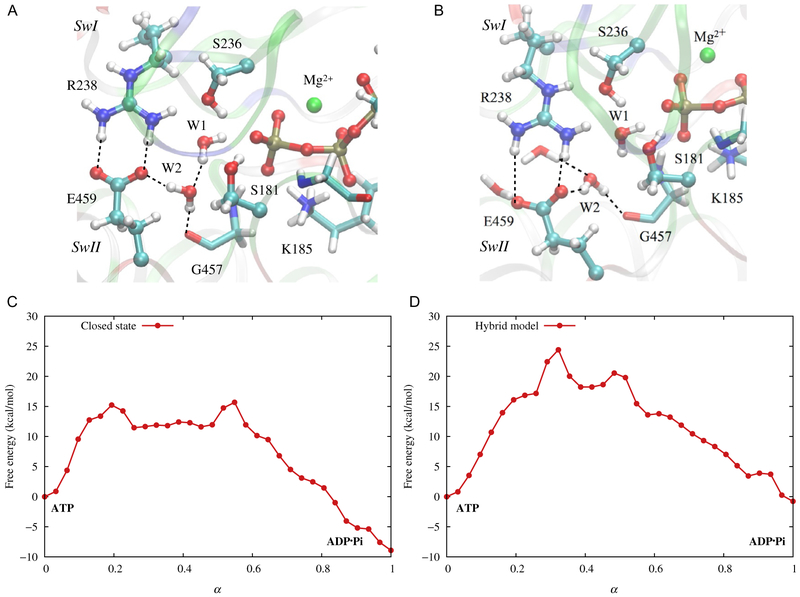

To probe how conformational properties impact the hydrolysis activity, we first need to establish the hydrolysis mechanism. We do so by performing QM/MM calculations for ATP hydrolysis in the crystal structure for the prepowerstroke state; this structure (Fig. 5A) was obtained with ADP·vanadate in the active site (Smith & Rayment, 1996), thus regarded as the state in which ATP is efficiently hydrolyzed.

Fig. 5.

Active-site structure of myosin and computed free energy profile for ATP hydrolysis. (A) The prepowerstroke state based on the crystal structure of the myosin motor domain complexed with ADP·vanadate (Smith & Rayment, 1996); (B) A computational “hybrid” model, in which the active-site protein residues are restrained to adopt the structure of the prepowerstroke state, while the rest adopts the postrigor crystal structure (Bauer et al., 2000). (C) and (D) Free energy profiles computed for the two structural models based on DFTB3/MM string calculations (Lu et al., 2017). Note that although the active-site structures are very similar in the two models, the hydrolysis free energy profiles are very different.

The mechanism of ATP hydrolysis in myosin has been analyzed by numerous experimental (Málnási-Csizmadia et al., 2001; Malnasi-Csizmadia et al., 2007; Onishi, Mochizuki, & Morales, 2004; Onishi, Ohki, Mochizuki, & Morales, 2002) and computational (Grigorenko et al., 2007; Kiani & Fischer, 2014; Li & Cui, 2004; Lu et al., 2017; Schwarzl, Smith, & Fischer, 2006; Yang & Cui, 2009; Yang, Yu, & Cui, 2008) investigations. For the purpose of this chapter, it is worth noting that debates remain regarding the identity of a catalytic base: one mechanism involves the γ phosphate of ATP as the ultimate base, although the proton transfer from the lytic water is likely mediated by active-site water molecules and/or polar side chains, while another mechanism involves a highly conserved glutamate (Glu459 in Dictyostelium discoideum myosin). While glutamate serving as the base for ATP/GTP hydrolysis has been supported in several other molecular motors such as F1-ATPase (Hayashi et al., 2012) and kinesin (McGrath et al., 2013), this role in myosin is not expected as Glu459 is engaged in a signature salt-bridge with Arg238; this interaction has been deemed essential to the closure of the active site and also expected to lower the pKa of Glu459, making it less likely to act as a base. Different computations, however, led to different conclusions (Grigorenko et al., 2007; Kiani & Fischer, 2014; Lu et al., 2017), and mutational studies involving this salt-bridge (Onishi et al., 2002) also led to results that were not straightforward to interpret (see below).

From a technical perspective, the mechanism of ATP hydrolysis is not straightforward to analyze using standard umbrella sampling methods. While the nucleophilic attack is well described by the antisymmetric stretch coordinate involving the lytic water oxygen, γ phosphorus (Pγ) and the bridging oxygen between the β and γ phosphates, proton transfer from the lytic water may occur through multiple routes and implicate different water molecules and amino acids in the active site. Coordinates that explicitly specify the identity of the “proton relay groups” are too restrictive and not appropriate for free energy simulations; coordinates that are collective in nature, such as those based on the center of excess charge (Koenig et al., 2006), are suitable for describing long-range proton transfers in which pathways involving rapidly exchanging water molecules are averaged over. However, coordinates that are highly collective in nature may also map very different structures onto the same region of the reaction coordinate space and thus compromises the physical meaningfulness of the free energy surface (see Fig. 6 for an example). Therefore, the strategy found effective in Lu et al. (2017) was to use metadynamics simulations to explore the reaction mechanism with delocalized collective variables; once a complete reaction pathway is sampled (it does not need to feature a converged free energy profile), the structures are fed into string calculations, which are able to use many more structural variables to uniquely define the pathway for meaningful free energy calculations.

Fig. 6.

Two active-site structures of the myosin motor domain have rather different bonding structures but very similar collective variables defined in metadynamics simulations (Lu et al., 2017) (CV1 is the antisymmetric stretch involving the breaking (P–O3β) and forming (OW-P) P–O bonds; CV2 is the antisymmetric stretch involving the location of the excess charge relative to Pγ and carboxylate oxygen of Glu459, ). As a result, they are mapped into the same region in the collective variable space, compromising the physical meaningfulness of the computed free energy surface.

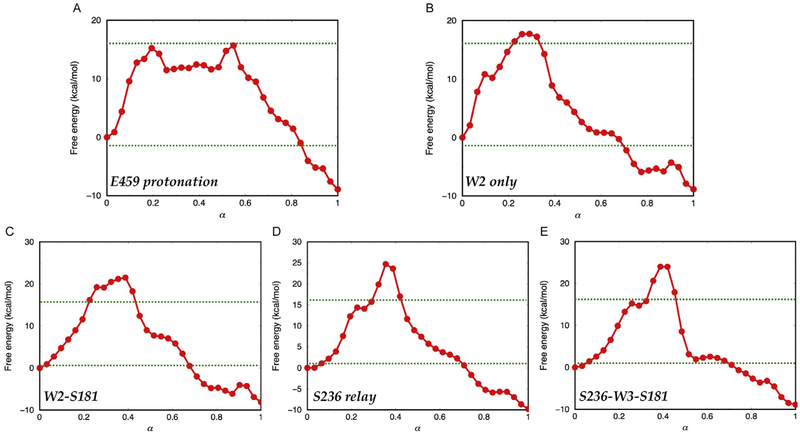

Using this strategy, five distinct reaction pathways were identified for ATP hydrolysis in the prepowerstroke state in essentially an automated fashion. The free energy profiles in Fig. 7 indicate different barriers but very consistent exothermicity, supporting the adequate convergence of the simulations; in terms of the amount of required sampling, the convergence behavior shown for one pathway indicates that on the order of 1 ns per image is required (Fig. 8), which is only feasible at the moment with semiempirical-based QM/MM simulations.

Fig. 7.

Free energy profiles computed for distinct reaction mechanisms of ATP hydrolysis in myosin using DFTB3/MM string simulations. Note that independent simulations lead to consistent exothermicities, supporting the convergence of the free energy simulations. As discussed in the text and in Lu et al. (2017), the exothermicity is overestimated with the DFTB3/MM approach. Experimental activation barrier and exothermicity (Geeves & Holmes, 1999, 2005) are indicated with dotted lines.

Fig. 8.

Example of convergence of DFTB3/MM string simulations for ATP hydrolysis in myosin. The results shown are for the hydrolysis in the postrigor state, which features a very high barrier and low exothermicity as expected. In (A), the root-mean-square-differences (RMSD) in the collective variables relative to the initial guess are shown as functions of the sampling time per image in the string simulations. In (B,C), the convergence behaviors of the free energy barrier and reaction exothermicity are shown with respect to the amount of sampling time per image.

Although the calculations do not have the required accuracy (see discussion in Section 3.1.3) to reliably rank the three low-barrier pathways, analysis of energetics along the multiple pathways indicates that the barrier is low when the hydronium is directly stabilized by Glu459. Indeed, among the low-free energy pathways, Glu459 either explicitly acts as the catalytic base (in the E459-protonation path) or participates indirectly by electrostatically stabilizing the hydronium during proton transfer (e.g., in the W2 only pathway). These observations are consistent with the significant reduction of ATPase activity in variants in which Glu459 is replaced by an alanine (Onishi et al., 2002). The result that the E459-protonation pathway features a low-free energy barrier is not contradictory to the expectation that the salt-bridge interaction with Arg238 lowers the pKa of Glu459; proton transfer to Glu459 was indeed found to be an uphill process, leading to a transient intermediate that is ~10 kcal/mol above the reactant state (Fig. 7A). Nevertheless, once the hydroxide is generated, the subsequent nucleophilic attack has only a modest barrier. Moreover, as illustrated in Fig. 9, active-site water molecules reorient to accommodate changes in protonation pattern throughout the reaction; these nonmonotonic changes in orientation are not straightforward to sample in minimization type of studies, which might explain the observation that the Glu459 pathway was found high in barrier in the minimum energy path-based calculations (Kiani & Fischer, 2014). Such a comparison highlights the importance of including proper thermal sampling in the study of complex chemical transformations in enzymes.

Fig. 9.

Water molecules in the active site rearrange during the hydrolysis reaction along the E459-protonation pathway (Lu et al., 2017).

3.2.2. Impact of Global Structural Transitions

To explore the roles of global structural transitions on the ATPase activity, we studied the hydrolysis reaction in a hybrid computational model, in which the active-site conformation in the postrigor crystal structure (Bauer et al., 2000) (which was obtained with ATP bound and clearly reflected a hydrolysis-incompetent state) was changed to that in the prepowerstroke structure through biased molecular dynamics simulations. As shown in Fig. 5B, the active site in the resulting hybrid structure closely resembles that in the prepowerstroke crystal structure (Fig. 5A), in terms of all amino acid side chains that are in direct contact with γ phosphate and the key salt-bridge between the SwI and SwII motifs. If ATP hydrolysis were strictly controlled by the “first coordination shell”, free energy profiles of hydrolysis computed with these two models are expected to be very similar. Rather surprisingly, the computed free energy profiles differ significantly (compare Figs. 5C and D); in the hybrid model, the hydrolysis is less exothermic by almost 10 kcal/mol, and the free energy barrier is also higher by ~ 9 kcal/mol. Evidently, hydrolysis is very much influenced by residues beyond the first and second coordination shell.

A close inspection of the active site in the two models indicates that water molecules therein behave differently. In the prepowerstroke conformation, the active site is well shielded from the bulk solvent and water molecules near the γ phosphate are engaged in a set of stable hydrogen-bonding interactions. In the hybrid “closed postrigor” model, although SwII is displaced to close the active site and establish more extensive interactions with ATP (e.g., through the main chain NH of Gly457), the other structural elements (e.g., the N-terminal loop of the relay helix) remain in the postrigor conformation (Yang et al., 2008). As a result, the active site remains, in fact, accessible to water; i.e., water molecules in the active site are in contact with the interfacial solvent molecules and more disordered compared to those in the prepowerstroke state (compare Figs. 5A and B). Another string calculation was conducted to estimate the free energy cost associated with reorganizing the active-site water molecules into configurations consistent with those in the prepowerstroke state; the penalty was found to be ~3 kcal/mol, which is significant but not the dominant contribution to the difference (~9 kcal/mol) between the free energy barriers in the two models. While further analysis is clearly warranted, the results support a model in which global structural transitions are important to catalysis; without these changes, the active site is not well set up for efficient chemistry even if key protein residues appear to be properly positioned; the effects may involve perturbation of active-site water orientations and reorganization energy, which contribute to the free energy of activation (Warshel et al., 2006). These considerations are reminiscent of the recurring observations from studies of natural enzymes and artificially evolved enzymes that remote mutations (Goodey & Benkovic, 2008; Schulenburg, Stark, Kunzle, & Hilvert, 2015; Tracewell & Arnold, 2009; Wang, Goodey, Benkovic, & Kohen, 2006), collectively, may lead to a significant impact on the chemical step in the active site.

3.2.3. Remaining Questions and Methodological Challenges

Numerous issues remain to be clarified. From a technical point of view, the accuracy of DFTB3 for multistep phosphoryl-transfer reactions needs to be improved. As shown in Fig. 7, the hydrolysis reaction in the prepowerstroke state is exothermic by almost 10 kcal/mol; the experimental data suggested that the hydrolysis is nearly thermoneutral (Geeves & Holmes, 1999). Studies of simple model reactions indicated that the error in exothermicity can be qualitatively understood (Lu et al., 2017), yet the issue of more concern is whether the DFTB3/MM approach captures the proper sequence of events between proton transfer and nucleophilic attack (Mlynsky et al., 2014); this affects the nature of the rate limiting transition state and therefore any factors that stabilize that transition state. Although gas phase models support the use of DFTB3 (Lu et al., 2017), more systematic calibration using solution phase model reactions will be valuable.

In terms of mechanistic details, the role of Glu459 needs to be further understood. In particular, mutation experiments involving the Arg238-Glu459 salt-bridge revealed several unexplained observations (Onishi et al., 2004, 2002). First, although this salt-bridge has been regarded as a key signature for the recovery stroke in myosin, mutation of either Arg238 or Glu459 did not abolish ATP binding or the recovery stroke; determining the structure and solvation of the active site in those variants will be informative. Second, while mutation of Glu459 into an alanine was, as expected, found to significantly reduce the ATP activity, a double mutant in which Arg238 and Glu459 were exchanged also had very low ATPase activity; whether this was due to significantly perturbed active-site water properties or altered electrostatics remains to be clarified. Considering the similarity in active-site structure among many biomolecular motors and GTPases, insights into these questions are likely transferable to other enzymes that employ nucleotide hydrolysis to drive other processes.

Concerning the role of global structural transitions, it is of interest to better understand the properties of active sites that are, on the one hand, essential to catalysis, and on the other hand, tightly coupled to global structural changes. In this regard, in addition to the average position of key residues (e.g., the population of configurations that are most conducive to catalysis), it is likely that their fluctuations are also important due to contribution to the reorganization energy (Warshel et al., 2006). A quantitative understanding beyond the continuum electrostatic analysis performed in Lu et al. (2017) (also see Swiderek, Tuñón, Moliner, & Bertran, 2015) requires QM/MM methodologies that are able to compute reorganization energies with well-defined decomposition of the QM region into chemically meaningful diabatic states (Mo & Gao, 2000). Moreover, structural transitions distant from the active site may also influence the activation free energy through entropic factors, as discussed in the context of temperature adaptation of enzymes (Aqvist, Kazemi, Isaksen, & Brandsdal, 2017; Isaksen, Aqvist, & Brandsdal, 2016). A reliable determination of entropic contributions, however, requires extensive sampling, for which further simplification of the QM model (e.g., with an empirical valence bond model) is likely productive, as demonstrated by Åqvist and coworkers in the analysis of several enzymes (Carvalho et al., 2015; Kazemi, Himo, & Aqvist, 2016).

4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this contribution, we discussed the application of QM/MM free energy simulations to two phosphoryl-transfer systems. The main goal is to illustrate the applicability of QM/MM methods, including some of the technical issues worthy of attention when applied to realistic enzymes (as opposed to active-site models) and the remaining limitations of the DFTB3-based methodologies. Although the DFTB3/MM method should be regarded as semiquantitative in nature, its computational efficiency compared to ab initio/DFT-based QM/MM calculations makes it particularly attractive in problems where trends are of most interest; in the case of AP, it is the trend in the nature of the transition state as the leaving group varies, and in the case of myosin, it is the trend in energetics with either different routes of proton transfers or with different structural models of the active site. Whenever possible, it is always valuable to supplement DFTB3/MM simulations with ab initio/DFT-based calculations, either with active-site models or QM/MM calculations of the realistic enzyme model through the MFEP approach. Ultimately, models that emerge from the computational analysis need to be tested with experiments, by either comparing to published data in the literature or explicitly documenting predictions (Roston et al., 2016) to stimulate new experimental tests. Along this line, the analysis of AP highlights that the interpretation of experimental data is not always straightforward, and calibrated computational models can be informative in identifying subtleties in the analysis.

In addition to the “Remaining Questions and Methodological Challenges” already summarized earlier, it is important to analyze processes other than the chemical step in phosphoryl-transfer enzymes because very often it is not the chemical step that controls the rate or functional specificity. For example, while the mechanism of large-scale conformational transitions has started to be explored at an atomic level for several kinases (Meng, Shukla, Pande, & Roux, 2016; Meng, Pond, & Roux, 2017; Shukla, Meng, Roux, & Pande, 2014; Zheng & Cui, 2018), it remains challenging to identify factors that dictate the rate of such transitions. Further progress along these lines is essential to obtaining a global understanding of phosphoryl-transfer enzymes, especially regarding their evolution and new strategies that regulate their activity for biomedical and biotechnological applications.

Fig. 1.

An active-site model for alkaline phosphatase (AP), with methyl p-nitrophenyl phosphate (MpNPP) as a substrate. Key geometrical parameters (in Å) are shown to compare DFTB3/3OB (with parentheses) and B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p);for additional comparisons, see Tables 2 and 3.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

D.R. was partially supported by an NIH NRSA Post-doctoral Fellowship (1F32GM112371-01A1), and D.D. was supported by an NIH Pre-doctoral Fellowshop (T32 GM008293). This research was also supported by an NIH grant (R01GM106443) and an XSEDE allocation (TG-MCB110014) to Q.C. Computational resources from the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE), which is supported by NSF grant number OCI-1053575, are greatly appreciated; computations are also partly supported by the National Science Foundation through a major instrument grant (CHE-0840494).

REFERENCES

- Alberts B, Bray D, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, & Watson JD (1994). Molecular biology of the cell. Garland Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews LD, Deng H, & Herschlag D (2011). Isotope-edited FTIR of alkaline phosphatase resolves paradoxical ligand binding properties and suggests a role for ground-state destabilization. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 133, 11621–11631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews LD, Fenn TD, &Herschlag D. (2013). Ground state destabilization by anionic nucleophiles contributes to the activity of phosphoryl transfer enzymes. PLOS Biology, 11 e1001599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Åqvist J, & Kamerlin SCL (2016). Conserved motifs in different classes of GTPases dictate their specific modes of catalysis. ACS Catalysis, 6, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar]

- Aqvist J, Kazemi M, Isaksen GV, & Brandsdal BO (2017). Entropy and enzyme catalysis. Accounts of Chemical Research, 50, 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barducci A, Bonomi M, & Parrinello M (2011). Metadynamics. WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 1, 826–843. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer CB, Holden HM, Thoden JB, Smith R, & Rayment I (2000). X-ray structures of the Apo and MgATP-bound states of Dictyostelium discoideum myosin motor domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275, 38494–38499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennie SJ, van der Kamp MW, Pennifold RCR, Stella M, Manby FR, & Mulholland AJ (2016). A projector-embedding approach for multiscale coupled-cluster calculations applied to citrate synthase. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 12 2689–2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobyr E, Lassila JK, Wiersma-Koch HI, Fenn TD, Lee JJ, Nikolic-Hughes I, … Herschlag D (2011). High-resolution analysis of Zn2+ coordination in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily by EXAFS and x-ray crystallography. Journal of Molecular Biology, 415, 102–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobyr E, Lassila JK, Wiersma-Koch HI, Fenn TD, Lee JJ, Nikolic-Hughes I, … Herschlag D (2012). High-resolution analysis of Zn2+ coordination in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily by EXAFS and x-ray crystallography. Journal of Molecular Biology, 415, 102–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boresch S, & Woodcock HL (2017). Convergence of single-step free energy perturbation. Molecular Physics, 115, 1200–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg JG, Hochheim M, Bredow T, & Grimme S (2014). Low-cost quantum chemical methods for noncovalent interactions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 5, 4275–4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk E, & Rothlisberger U (2015). Mixed quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical molecular dynamics simulations of biological systems in ground and electronically excited states. Chemical Reviews, 115, 6217–6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J, & di Fagagna F (2007). Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 8, 729–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho ATP, Szeler K, Vavitsas K, Åqvist J, & Kamerlin SCL (2015). Modeling the mechanisms of biological GTP hydrolysis. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 582, 80–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catrina I, O’Brien PJ, Purcell J, Nikolic-Hughes I, Zalatan JG, Hengge AC, & Herschlag D (2007). Probing the origin of the compromised catalysis of E-coli alkaline phosphatase in its promiscuous sulfatase reaction. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 129, 5760–5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AS, Kubar T, Cui Q, & Elstner M (2016). Semi-empirical quantum mechanical methods for non-covalent interactions for chemical and biochemical applications. Chemical Reviews, 116, 5301–5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeyssens F, Harvey JN, Manby FR, Mata RA, Mulholland AJ, Ranaghan KE, … Werner HJ (2006). High-accuracy computation of reaction barriers in enzymes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 45, 6856–6859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland WW, & Hengge AC (2006). Enzymatic mechanisms of phosphate and sulfate transfer. Chemical Reviews, 106, 3252–3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P (2002). Protein kinases - The major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 1, 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins I, & Workman P (2006). Design and development of signal transduction inhibitors for cancer treatment: Experience and challenges with kinase targets. Current Signal Transduction Therapy, 1, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer CJ, & Truhlar DG (2009). Density functional theory for transition metals and transition metal chemistry. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 11, 10757–10816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q (2016). Quantum mechanical methods in biochemistry and biophysics. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 145, 140901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, & Karplus M (2003). Catalysis and specificity in enzymes: A study of tri-osephosphate isomerase (TIM) and comparison with methylglyoxal synthase (MGS). Advances in Protein Chemistry, 66, 315–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, & Cohen P (2000). Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochemical Journal, 351, 95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dral PO, Wu X, Sporkel L, Koslowski A, & Thiel W (2016). Semiempirical quantum-chemical orthogonalization-corrected methods: Benchmarks for ground-state properties. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 12, 1097–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte F, Amrein BA, & Kamerlin SCL (2013). Modeling catalytic promiscuity in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 15, 11160–11177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinan E, & Vanden-Eijnden E (2010). Transition-path theory and path-finding algorithms for the study of rare events. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 61, 391–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elstner M, Hobza P, Frauenheim T, Suhai S, & Kaxiras E (2001). Hydrogen bonding and stacking interactions of nucleic acid base pairs: A density-functional-theory based treatment. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 114, 5149–5155. [Google Scholar]

- Elstner M, Porezag D, Jungnickel G, Elsner J, Haugk M, Frauenheim T, … Seifert G (1998). Self-consistent-charge density-functional tight-binding method for simulations of complex materials properties. Physical Review B, 58(11), 7260–7268. [Google Scholar]

- Flaig D, Beer M, & Ochsenfeld C (2012). Convergence of electronic structure with the size of the QM region: Example of QM/MM NMR shieldings. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 8, 2260–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian J, Aqvist J, & Warshel A (1998). On the reactivity of phosphate monoester dianions in aqueous solution: Bronsted linear free-energy relationships do not have an unique mechanistic interpretation. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 120, 11524–11525. [Google Scholar]

- Florian J, & Warshel A (1998). Phosphate ester hydrolysis in aqueous solution: Associative versus dissociative mechanisms. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 102, 719–734. [Google Scholar]

- Friesner RA, & Guallar V (2005). Ab intio QM and QM/MM methods for studying enzyme catalysis. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 56, 389–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JL, Amara P, Alhambra C, & Field MJ (1998). A generalized hybrid orbital (GHO) method for the treatment of boundary atoms in combined QM/MM calculations. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 102, 4714–4721. [Google Scholar]

- Gao JL, Ma SH, Major DT, Nam K, Pu JZ, & Truhlar DG (2006). Mechanisms and free energies of enzymatic reactions. Chemical Reviews, 106, 3188–3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JL, & Truhlar DG (2002). Quantum mechanical methods for enzyme kinetics. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 53, 467–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, & Karplus M (2004). Biomolecular motors: The F1-ATPase paradigm. Current Opinion in Structural Biology, 14, 250–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber K (2001). Rapamycin’s resurrection: A new way to target the cancer cell cycle. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 93, 1517–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Viloca M, Gao J, Karplus M, & Truhlar DG (2004). How enzymes work: Analysis by modern rate theory and computer simulations. Science, 303, 186–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaus M, Cui Q, & Elstner M (2011). DFTB-3rd: Extension of the self-consistent-charge density-functional tight-binding method SCC-DFTB. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 7, 931–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaus M, Cui Q, & Elstner M (2014). Density functional tight binding (DFTB): Application to organic and biological molecules. WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 4, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Gaus M, Goez A, & Elstner M (2012). Parametrization and benchmark of DFTB3 for organic molecules. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 9, 338–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaus M, Jin H, Demapan D, Christensen AS, Goyal P, Elstner M, & Cui Q (2015). DFTB3 parametrization for copper: The importance of orbital angular momentum dependence of Hubbard parameters. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 11, 4205–4219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaus M, Lu X, Elstner M, & Cui Q (2014). Parameterization of DFTB3/3OB for sulfur and phosphorus for chemical and biological applications. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 10, 1518–1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeves MA, & Holmes KC (1999). Structural mechanism of muscle contraction. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 68, 687–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeves MA, & Holmes KC (2005). The molecular mechanism of muscle contraction. Advances in Protein Chemistry, 71, 161–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genna V, Vidossich P, Ippoliti E, Carloni P, & De Vivo M (2016). A self-activated mechanism for nucleic acid polymerization catalyzed by DNA/RNA polymerases. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 138, 14592–14598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodey NM, & Benkovic SJ (2008). Allosteric regulation and catalysis emerge via a common route. Nature Chemical Biology, 4, 474–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal P, Qian HJ, Irle S, Lu X, Roston D, Mori T, … Cui Q (2014). Feature article: Molecular simulation of water and hydration effects in different environments: Challenges and developments for DFTB based models. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 118, 11007–11027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig IR (2010). The analysis of enzymic free energy relationships using kinetic and computational models. Chemical Society Reviews, 39, 2272–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko BL, Rogov AV, Topol IA, Burt SK, Martinez HM, & Nemukhin AV (2007). Mechanism of the myosin catalyzed hydrolysis of ATP as rationalized by molecular modeling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 7057–7061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S, Hansen A, Brandenburg JG, & Bannwarth C (2016). Dispersion-corrected mean-field electronic structure methods. Chemical Reviews, 116, 5105–5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Uchida Y, Hasegawa T, Higashi M, Kosugi T, & Kamiya M (2017). QM/MM geometry optimization on extensive free-energy surfaces for examination of enzymatic reactions and design of novel functional properties of proteins. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 68, 135–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Ueno H, Shaikh AR, Umemura M, Kamiya M, Ito Y, … Noji H (2012). Molecular mechanism of ATP hydrolysis in F-1-ATPase revealed by molecular simulations and single-molecule observations. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 134(20), 8447–8454. 10.1021/ja211027m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengge AC (2002). Isotope effects in the study of phosphoryl and sulfuryl transfer reactions. Accounts of Chemical Research, 35, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou GH, & Cui Q (2012). QM/MM analysis suggests that alkaline phosphatase (AP) and nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (NPP) slightly tighten the transition state for phosphate diester hydrolysis relative to solution: Implication for catalytic promiscuity in the AP superfamily. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 134, 229–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou GH, & Cui Q (2013). Stabilization of different types of transition states in a single enzyme active site: QM/MM analysis of enzymes in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 135, 10457–10469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, & Yang WT (2008). Free energies of chemical reactions in solution and in enzymes with ab initio quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics methods. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry, 59, 573–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LH, Soderhjelm P, & Ryde U (2011). On the convergence of QM/MM energies. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 7, 761–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaksen GV, Aqvist J, & Brandsdal BO (2016). Enzyme surface rigidity tunes the temperature dependence of catalytic rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 7822–7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks WP (1985). A primer for the BEMA HAPOTHLE—An empirical approach to the characterization of changing transition-state structure. Chemical Reviews, 85, 511–527. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Laury ML, Powell M, & Wilson AK (2012). Comparative study of single and double hybrid density functionals for the prediction of 3d transition metal thermochemistry. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 8, 4102–4111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal G, & Warshel A (2016). Exploring the dependence of QM/MM calculations of enzyme catalysis on the size of the QM region. Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 120, 9913–9921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas S, & Hollfelder F (2009). Mapping catalytic promiscuity in the alkaline phosphatase superfamily. Pure and Applied Chemistry, 81, 731–742. [Google Scholar]

- Kamerlin SCL, Haranczyk M, & Warshel A (2009). Progress in ab initio QM/MM free-energy simulations of electrostatic energies in proteins: Accelerated QM/MM studies of pK(a), redox reactions and solvation free energies. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 113, 1253–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamerlin SCL, Sharma PK, Prasad RB, & Warshel A (2013). Why nature really chose phosphate. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics, 46, 1–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi M, Himo F, & Aqvist J (2016). Enzyme catalysis by entropy without circe effect. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 2406–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiani FA, & Fischer S (2014). Catalytic strategy used by the myosin motor to hydrolyze ATP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(29), E2947–E2956. 10.1073/pnas.1401862111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiani FA, &Fischer S (2016). Comparing the catalytic strategy of ATP hydrolysis in biomolecular motors. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 18, 20219–20233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiaris H, & Spandidos DA (1995). Mutations of Ras genes in human tumors. International Journal of Oncology, 7, 413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles JR (1980). Enzyme catalyzed phosphoryl transfer reactions. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 49, 877–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]