Abstract

Gliomas are heterogeneous tumors derived from glial cells and remain the deadliest form of brain cancer. Although the glioma stem cell sits at the apex of the cellular hierarchy, how it produces the vast cellular constituency associated with frank glioma remains poorly defined. We explore glioma tumorigenesis through the lens of glial development, starting with the neurogenic-gliogenic switch and progressing through oligodendrocyte and astrocyte differentiation. Beginning with the factors that influence normal glial lineage progression and diversity, a pattern emerges that has useful parallels in the development of glioma, and may ultimately provide targetable pathways for much needed new therapeutics.

Introduction

Developmental contributions to tumorigenesis have long been viewed through the lens of stem cell biology, where developmental programs are thought to regulate gross differentiative states, and provide the cellular substrates for malignant growth. However cancer stem cells comprise a small fraction of the primary tumor, with the vast majority of the remaining tumor mass comprised of differentiated derivatives of the stem cell. These observations, coupled with the inherent cellular heterogeneity within a tumor, have led to the hypothesis that the tumor is a developing organ–tissue system that requires lineage specific developmental programs to produce the diverse range of cells necessary to execute key cancer “hallmark” properties that engender malignancy1.

The outcome of any developmental process is the production of mature lineages that contribute to the physiological function of a given tissue. In malignancy, the processes that generate these cells are subverted, resulting in the aberrant production of lineage-associated cells that comprise the tumor.

Genetic mutation is known to drive malignant growth, and operates in part by “hijacking” developmental programs as a mechanism for generating tumor cells2. Illustrating the intersection between development and malignancy are the direct roles played by core developmental pathways (Wnt, Shh, BMP and Notch)3 in tumorigenesis, the influence of many generic drivers of malignancy (p53, PTEN, p16)4-6 on development, and the fact that many key developmental genes are frequently mutated in cancer as well (EGFR, Notch, Shh)7,8. Emerging from these observations is a molecular and functional interdependence between classic drivers of cancer and developmental pathways that engenders malignancy. Using the interface between development and malignancy as our guide, this review will describe the cellular and molecular mechanisms that oversee the development of central nervous system (CNS) glia and identify the unifying characteristics between normal glial development and the generation of their malignant counterparts in glioma.

A Developmental Framework for Glioma

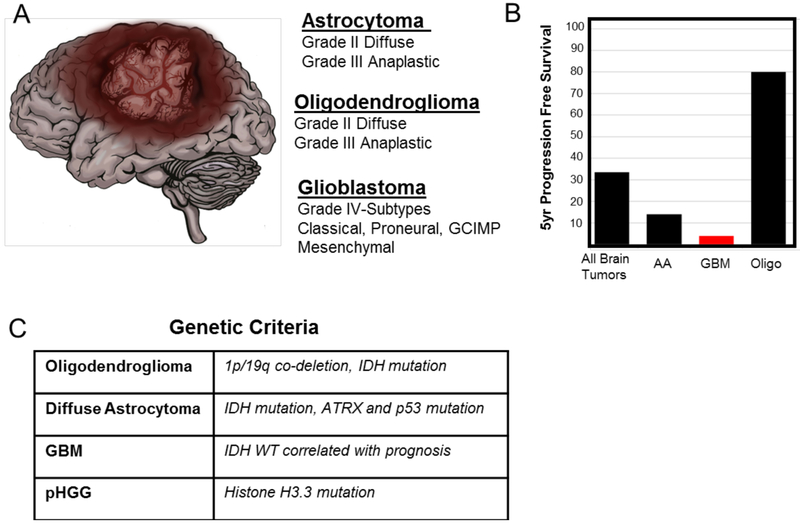

There are two broad categories of CNS glia: oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. Oligodendrocytes form the myelin sheath that surrounds axons and is essential for saltatory nerve conduction9. Astrocytes occupy a variety of roles essential for homeostatic CNS function, including formation of the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB), buffering neurotransmistter levels, formation of synapses, and providing metabolic support to neurons10. Accordingly, the brain offers an extraordinary degree of lineage complexity and a broad spectrum of associated malignancies. Amongst forms of brain cancer, diffuse gliomas are the most frequent and have the worst prognosis. Diffuse gliomas are comprised of three categories: astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma and glioblastoma (Figure 1)11. As suggested by the respective names of the glioma subtypes, oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma, these tumors share common features of their normal counterparts, including histological, functional, and molecular characteristics. Furthermore, astrocytomas can also recur after primary intervention as secondary glioblastoma. Diagnosis of diffuse glioma has integrated classic histological analysis and newly identified genetic criteria, with IDH status and co-deletion of 1p/19q serving as key genetic landmarks11. Amongst diffuse glioma (herein glioma), glioblastoma (GBM) is the most frequent and has the worst prognosis. Accordingly, GBM has been the subject of intense scrutiny over the years, with recent profiling efforts identifying five molecular sub-groups of GBM12,13.

Figure 1. Overview of Glioma Subtypes.

Gliomas have been classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ranging from low grade astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas to high grade astrocytomas or glioblastoma using histopathological and genetic parameters. A. Summary of the predominant subtypes of adult glioma based on the 2016 WHO Classification11. B. Comparison of 5 year progression–free survival rates for different tumor subtypes, which represents the percentage of people whose glioma has not worsened 5 years after treatment. Data are derived from the following sources: American Cancer Society, National Brain Tumor Society, and ref101. AA-Anaplastic Astrocytoma, GBM-Glioblastoma, Oligo-Diffuse and Anaplastic Oligodendroglioma. Note the AA and GBM have significantly worse outcomes than all other forms of brain tumors and oligodendroglioma. C. Common genetic criteria for glioma subtypes are list. Gliomas are diagnosed by histopathological name and genetic features. For example a glioma subtype would be represented as oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q codeletion. Genetic criteria used to classify glioma subtypes were derived from 11. Recently, the WHO has reclassified glioma subtypes based on a set of defining genetic mutations. These defining mutations are shown in C. While pediatric high-grade glioma is histologically indistinguishable from adult GBM, it is considered distinct from adult GBM because the spectrum of driver mutations is considerably different14,15.

Despite common histopathological features, pediatric high-grade glioma (pHGG) is considered distinct from its adult counterpart, as it is associated with unique anatomical locations, responses to radiotherapy, and clinical outcomes14. Moreover, pHGG has significantly less somatic mutations than adult gliomas, with hallmark mutations occurring in histone H3.3 that infer an epigenetic origin of disease15,16 (Figure 1). Finally, pHGG occurs in the developing brain, further distinguishing it from adult glioma, suggesting it may exploit active proliferative and migratory programs in this neurodevelopmental context. Despite these advances in both adult and pediatric glioma, survival rates have not significantly changed in over 70 years, highlighting the need for new interventions, driven by a deeper understanding of the underlying biology of this malicious disease.

Over the past decade advances in genomics have delivered critical insights that have shaped the cataloging of tumor subtypes, while the discovery of the glioma stem cell (GSC) has guided functional studies on the origins and recurrent nature of this disease17. While the GSC sits at the apex of the cellular hierarchy, how it produces the vast cellular constituency associated with frank glioma tumorigenesis remains very poorly defined. Given that the vast majority of cells comprising malignant glioma are glial in nature, one way of deciphering how these tumor cells are produced is to understand how glial developmental processes are utilized during tumorigenesis. Thus, the central hypothesis that we will explore in this review will be: if we can understand how to make glial cells, then we can better understand glioma tumorigenesis.

Importantly, while there are clear parallels between brain development and glioma tumorigenesis, much of what we know about the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying developmental gliogenesis has been discerned from the spinal cord. The spinal cord is often used as an archetype for CNS development because it’s relatively simple anatomy and accessibility makes it a tractable system in which to conduct complex molecular studies. Moreover, all the major neurogenic transcription factors and signaling pathways have been shown to play similar roles in both the spinal cord and the developing cortex. These observations indicate that there is a strong conservation of gene and pathway function across these CNS regions and provide a rationale for exploring gliogenic mechanisms that control spinal cord development as a developmental canvas upon which we can understand glioma tumorigenesis.

Neural Stem Cell–Glial Progenitor Axis

The Gliogenic Switch

Given the intimate association between glioma and glial cells, developmental gliogenesis serves as a natural starting point for building a developmental framework for glioma. If the GSC sits at the apex of the tumor hierarchy and is responsible for the generation of glioma cells that populate the bulk tumor, the analogous relationship in development is the neural stem cell – glial progenitor axis. Given this, we will begin with an overview of early gliogenesis, focusing on the gliogenic switch.

Mammalian gliogenesis consists of three separate processes that ensure the progenitor pool produces the proper number of glia. First, the processes that promote neurogenesis must be inhibited to allow for gliogenesis. Second, the progenitor pool must also be maintained, to protect against depletion. Finally, progenitor populations must produce a set number of glial cells. This developmental interval has been termed the “gliogenic switch” and is used across diverse CNS regions and model organisms to initiate gliogenesis.

Much of what we know about the gliogenic switch comes from studies in the developing mouse spinal cord, where the timing of this transition is clearly, defined: neurogenesis ceases at E11.5 and gliogenesis commences at E12.5 (Figure 2). Using the pMN domain in spinal cord as a model system, deletion and fate mapping studies have shown that progenitor populations during gliogenic stages are generated after neurogenesis, suggesting that neurons and glia are generated from distinct progenitors18,19. This concept was reinforced by studies in zebrafish demonstrating that gliogenic progenitors are recruited to the pMN domain after neurogenesis20. Moreover, heterochronic transplantation studies in the developing CNS with freshly isolated neurogenic and gliogenic populations demonstrate stark phenotypic differences between these embryonic populations: neurogenic populations are multi-potent, while gliogenic populations are not 21. Together, these studies suggest that the cellular substrates giving rise to neurons and glia have unique properties and may also have distinct origins.

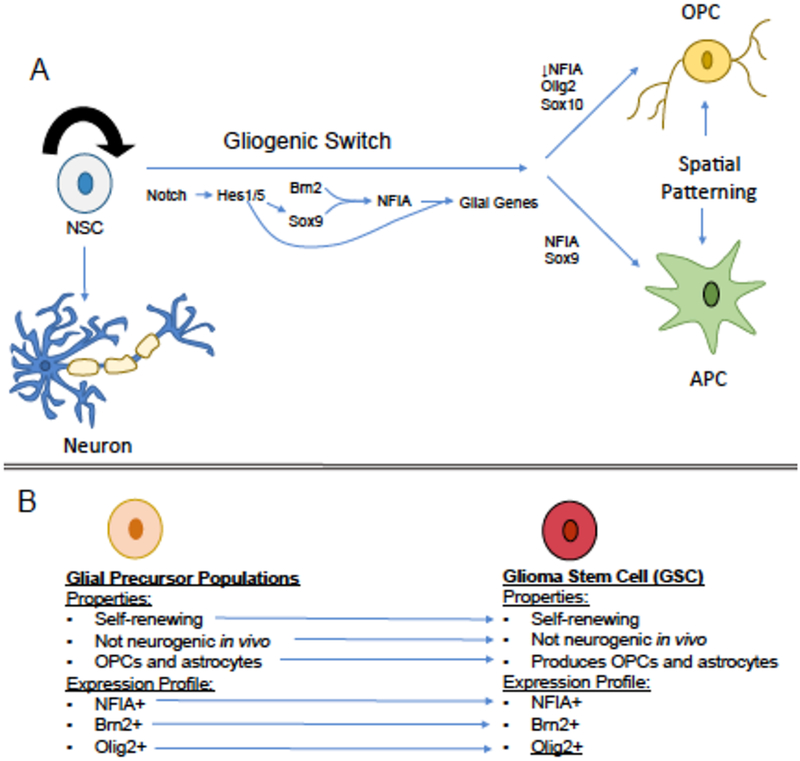

Figure 2. The Gliogenic Switch and Glioma.

A) Illustration of the cellular and transcriptional events that occur during the gliogenic switch in the developing spinal cord. Neural stem cell populations (NSCs) are self-renewing (indicated by curved arrow) and are present during neurogenesis around embryonic day 9.5(E9.5) to E11. The gliogenic switch occurs around E12.5 where NSCs are gradually replaced by glial progenitor populations (GPC), astrocyte precursors (APC) and oligodendrocyte precursors (OPC). Notch functions throughout the gliogenic switch interval to maintain the glial progenitor pool, while Brn2 and Sox9 collaborate to drive NFIA induction. It’s important to note that APCs and OPCs are generated in distinct progenitor domains within the developing brain and accordingly, spatial patterning mechanisms also contribute to specifying their identities. B) There are a number of molecular and functional properties that are conserved between GPC and glioma stem cell (GSC) populations. These parallels suggest that the GSC behaves like glial precursor populations.

These cellular observations correspond with molecular changes that play vital roles in determining the initiation of glial fate during the gliogenic switch. Among these molecular changes, the induction of the transcription factors Sox9 and Nuclear factor 1A (NFIA) play essential roles during the initiation of gliogenesis. Sox9 is induced in progenitor populations around E10.5 and its deletion results in a delay in the onset of gliogenesis and concordant extension of the neurogenic phase22. NFIA is induced at E11.5 in the spinal cord and studies in the embryonic chick spinal cord revealed that it is necessary and sufficient for gliogenesis23. Additional studies have shown that Sox9 and Brn2 directly regulate NFIA induction and that Sox9 and NFIA collaborate to drive expression of early glial genes24,25. From these studies a transcriptional regulatory cascade emerges, where Sox9 and Brn2 directly regulate NFIA induction and subsequently form protein partnerships to further promote glial differentiation.

Among the central developmental pathways, Notch signaling plays an essential role during the gliogenic switch. Deletion of Notch effectors, Hes1 and Hes5, results in precocious neuronal differentiation and a complete loss of glia26. Complementary increases in Notch signaling produce more glia, suggesting that Notch signaling is instructive27. However, studies in zebrafish and chick have shown that while enhanced Notch activity produces more glia, these cells are not generated at earlier timepoints, suggesting that Notch facilitates the gliogenic switch by maintaining the progenitor pool23,27. Nevertheless, there is evidence that Notch function may be coordinated with Sox9 and NFIA. Notch signaling can regulate Sox9 expression in the developing spinal cord and NFIA collaborates with Notch effectors to drive GFAP expression in astrocytes and may directly regulate expression of Hes genes23,28,29.

The Gliogenic Switch and Glioma

Applying the cell biology underlying the gliogenic switch to glioma remains challenging because of the clear operational differences between a NSC and GSC: in vivo neurogenic capacity, NSCs have it and GSCs do not (Figure 2). Thus it is unlikely that a bona fide NSC exists within a tumor. Instead the existing GSCs likely resemble the glial precursor populations present after the gliogenic switch. In support of this notion, recent profiling studies identified Sox2, Brn2, and Olig2 as part of a transcriptional node present in GSCs30. Moreover, NFIA expression in glioma is tightly correlated with Brn2, providing additional molecular evidence that GSCs may be endowed with glial precursor properties25. Also, adult NSCs in the subventricular (SVZ) and subgranular (SGZ) zones express several glial markers, further supporting the glial nature of these populations. Nevertheless, it is possible that genetic mutation, coupled with selective pressures, produce a GSC population that has co-opted both NSC and glial identities. Alternatively, it is possible that the bulk GSC population is comprised of multiple subpopulations with these distinct glial- and NSC-like properties. Indeed, recent clonal mapping of GSCs identified discrete clones that are resistant to chemotherapy, suggesting that functional heterogeneity exists within this population31.

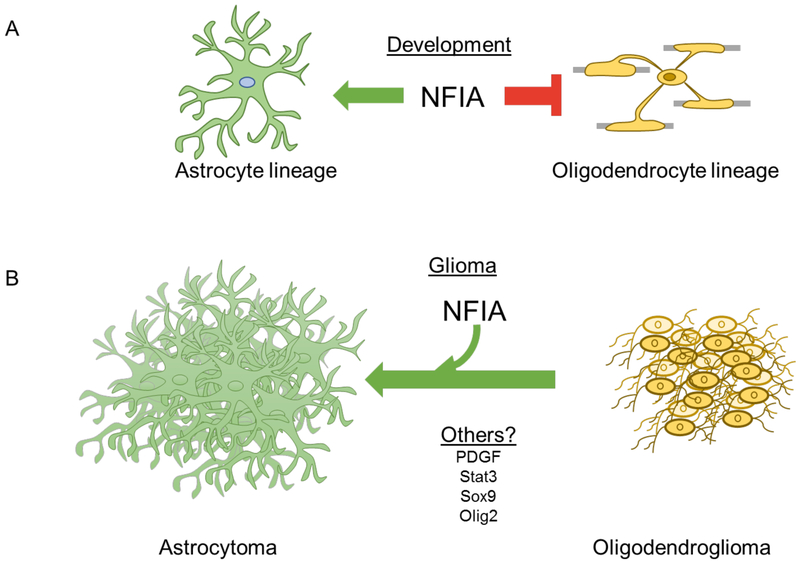

Because glioma tumors exhibit features consistent with glial precursor populations, a natural question that emerges is whether the developmental determinants of glial cell fate also contribute to tumorigenesis. Towards this, several recent studies on NFIA and Sox9 have highlighted the critical role these factors play in glioma tumorigenesis. NFIA is highly expressed in all grades of astrocytoma and GBM, while functional studies in human and mouse glioma cell lines have shown that it regulates glioma tumorigenesis via direct transcriptional repression of p2132-34. Although these studies reveal a general role in glioma proliferation in xenograft models, studies in native mouse models reveal that overexpression of NFIA can convert an oligodendroglioma subtype to an astrocytoma34. This observation suggests that manipulating glial fate determinants can alter tumor “identity” and points to the possibility of differentiation therapy for glioma via these developmental mechanisms (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Glial Developmental Factors Influences Tumor “Identity”.

A) NFIA functions to promote astrocyte lineage development and suppress the maturation of oligodendrocytes. Consistent with this developmental observation, NFIA is highly expressed in astrocytoma, but demonstrates scant expression in oligodendroglioma33. (B) Functional studies in endogenously generated mouse models of oligodendroglioma indicate that overexpression of NFIA can convert an oligodendroglioma to an astrocytoma25. These observations are consistent with its developmental role in promoting the astrocyte fate at the expense of the oligodendrocyte fate and suggest that manipulating glial fate determinants may influence the sub-type or identity of the glioma. In the future, it will be important to test this hypothesis with other transcriptional and signaling determinants of glial fate, as this approach may be harnessed for differentiation therapy. A list of candidate transcription factors and signaling pathways that play crucial roles in glial development and are implicated in glioma tumorigenesis is provided.

Although Sox9 is also highly expressed in glioma, its role is not as clearly defined35. Studies in glioma cell lines have shown that Sox9 promotes proliferation and tumorigenesis in xenografts, but the underlying mechanisms remain poorly defined36. Studies in another form of brain cancer, medulloblastoma, have shown that Sox9 is linked to n-myc and Shh signaling, suggesting that parallel mechanisms may also apply to glioma37. Additional evidence of a role for Sox9 in glioma comes from recent studies showing that deletion of Sox9- and Brn2-regulated enhancers in the NFIA locus not only inhibits NFIA expression, but also inhibits tumorigenesis in a native mouse model of glioma25. Although these observations do not directly demonstrate a function for Sox9 and Brn2 in glioma tumorigenesis, they strongly suggest that the regulatory relationships overseeing the gliogenic switch are present in glioma and directly contribute to tumorigenesis.

Given its central role in progenitor maintenance in the CNS, the role of the Notch pathway in glioma tumorigenesis and the expression of pathway components have been extensively investigated38. Functional studies have been performed predominately in GSC models, where Notch has been shown to promote both in vitro growth and tumorigenesis in xenografts. Several clinical trials have utilized approaches geared towards inhibiting Notch activity in glioma, albeit with limited success, partly due to the inherit complexity of the pathway and context-specific functions of Notch signaling38. For example, knockdown of RBPJ, a key effector of Notch signaling, in human GSC models inhibited tumorigenesis, while deletion of RBPJ in a PDGF-driven native mouse model accelerated tumor growth39,40. These seemingly disparate findings highlight the importance of cellular and genetic context when manipulating Notch signaling. Moreover, recent profiling studies using RTK inhibitor-resistant GSC populations identified a Notch activated developmental program that promotes expression of key gliogenic genes, including Olig2, NFIA, and multiple Sox-genes41. These finding further illustrate the importance of cellular and environmental context when examining Notch function and reinforce the links between prospective GSC populations and the transcriptional mechanisms regulating the gliogenic switch. Finally, we must also consider the possibility that Notch may not be essential for glioma tumorigenesis, making it a flawed target or that current pharmacological inhibitors are not effective or are non-specific in the context of glioma.

Oligodendrocytes: a nexus for glioma?

After NSCs initiate gliogenesis via the gliogenic switch, the resultant glial precursors subsequently differentiate into the two glial sub-lineages: oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. The generation of each glial sub-lineage is the result of a series of differentiative steps, culminating in the production of a physiologically mature cell6,42. Importantly, each of these steps is governed by a distinct set of transcription factors and signaling pathways, some of which are also are also implicated in glioma tumorigenesis.

Oligodendrocyte Lineage Development

Among cells of the CNS, the oligodendrocyte lineage is one of the best characterized, both in terms of the lineage’s progressive differentiation as well as markers for the specific stages of lineage progression43,44. Because of this progressive nature of differentiation, oligodendrocytes can be used as a paradigm for better understanding lineage dysregulation during malignant glioma.

During their development, oligodendrocytes progress from specified oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) that occupy discrete germinal centers (pMN in spinal cord and MGE, LGE in cortex) to migratory premyelinating oligodendrocytes, and finally to mature myelinating oligodendrocytes (Figure 4). This course of differentiation begins around E13.5, with myelination commencing during early perinatal stages and continuing throughout post-natal development. During this differentiation process, OPCs exit the cell cycle, begin expressing genes required for myelination, and undergo a number of morphological changes important for their physiological role in axon ensheathment. However, not all OPC populations differentiate into myelin-producing oligodendrocytes. This is in stark contrast to neuronal- and astrocyte-precursor populations, which do not reside in the adult CNS, resident OPC populations are maintained in the adult CNS and retain their proliferative, migratory, and differentiative potential45. These properties of OPCs in the adult have important implications for the origins of glioma (see below)

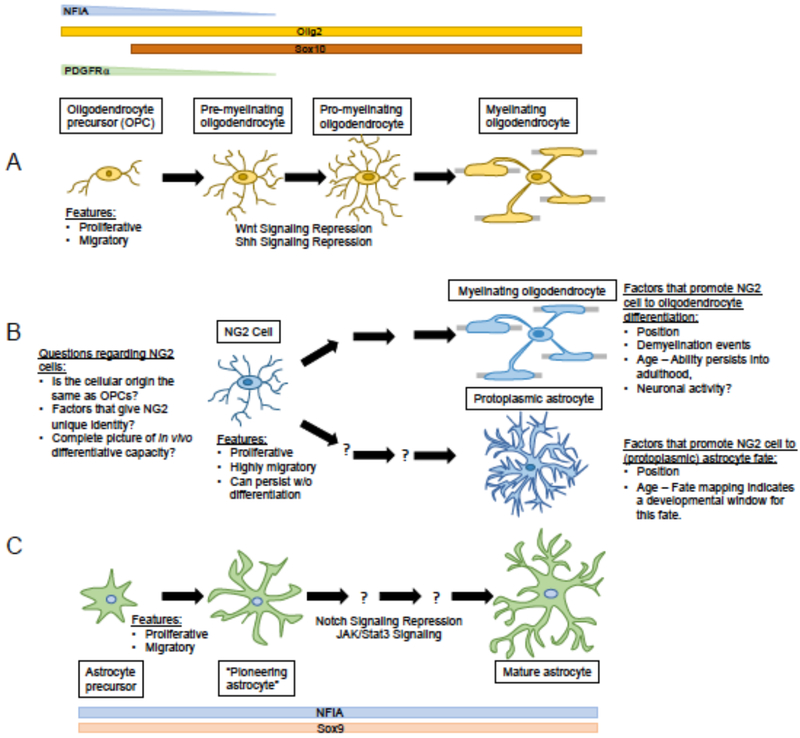

Figure 4. Astrocyte and Oligodendrocyte Lineage Trajectories.

A) Phases of oligodendrocyte lineage development and depiction of Olig2, Sox10, and PDGFRa expression. As oligodendrocytes develop NFIA and PDGFRa are downregulated while Olig2 and Sox10 expression are maintained as maturation and myelination occur. During oligodendrocyte maturation, cells lose their proliferative and migratory capacity, coinciding with Wnt and Shh signaling repression. B) NG2 Glia as a resident OPC population in the adult CNS. NG2 glia, although similar to other precursor populations in the CNS in their proliferative and migratory capacity, can potentially give rise to oligodendrocytes and protoplasmic astrocytes in vivo. NG2 glia express NG2 and PDGFRa in conjunction with Olig2. Olig2 expression persists in NG2 cells that differentiate into myelinating oligodendrocytes. However, NG2 glia fated to become protoplasmic astrocytes lose Olig2 expression and begin expressing astrocyte markers such as GFAP and ALDH1L1. Numerous issues regarding the cellular origin of these cells and the full range of downstream cell fates remain to be adequately established. (C) Phases of astrocyte lineage development and depiction of NFIA, Sox9, Aldh1l1, and GFAP expression. The various stages of astrocyte lineage development remain poorly defined; the “pioneering” astrocyte is a feature of the developing cortex, and analogous population in the developing spinal cord has been termed the “Intermediate Astrocyte Precursor” IAP. Over the course of this development, Notch signaling repression and JAK/Stat3 signaling activation initiates astrocyte maturation. A unifying feature of OPCs, NG2-cells, IAP and “pioneering” astrocytes is proliferation and migration outside the germinal centers. These are fundamental properties of glioma tumor cells, suggesting parallel populations may exist in tumors, highlighting the need to further delineate the properties of intermediate astrocyte lineage populations.

These resident OPC populations express the NG2 antigen, have been termed “NG2 cells” and are often considered a separate class of glial cell (Figure 4). Despite their relatively uniform distribution across the brain NG2 cells exhibit diverse developmental potentials, where populations in white matter more prone to generate myelin, than those in the grey matter46. Interestingly, subsets of NG2 cells have the potential to generate astrocytes during late developmental, but this capacity is lost in post-natal stages, suggesting plasticity in their cellular potentials during development47. Moreover, because subsets of NG2 cells have varying developmental potential towards myelination and astrocyte production, suggests a hidden reservoir of diverse NG2 subpopulations that remain to be defined48.

The molecules that distinguish the phases of oligodendrocyte lineage development and the transcription factors that oversee this process are well described43,44. Here, we will focus on key transcription factors that operate in OPCs to control the early phases of lineage development. Among this cohort is Olig2, which is expressed in the ventral spinal cord in a Shh-dependent manner49. Olig2 is required for the production of motor neurons and following the gliogenic switch is required for the subsequent generation of OPCs in both the spinal cord and the cortex50. Expression of Olig2 persists following the maturation of OPCs into myelinating oligodendrocytes and also is found in adult OPC populations where it similarly contributes to their ability to differentiate into myelinating oligodendrocytes.

Another key transcription factor that operates in OPCs is Sox10, which is exclusively expressed in the oligodendrocyte lineage and is induced by Olig2 in OPCs at the onset of gliogenesis51. Sox10 appears to play multiple roles in oligodendrocyte development, as it regulates PDGFRa expression in OPCs and also induces expression of myelin genes later in lineage development51,52. These key roles are supported by genetic studies in mice demonstrating that Sox10 is required for OPC differentiation. In addition to their roles in promoting OPC development, another facet of Olig2 and Sox10 function is the suppression of astrocyte development. In Olig2 and Sox10 mutant mice, erstwhile OPC populations are converted to astrocytes25,50. Mechanistically, Olig2 and Sox10 function to antagonize the ability of NFIA and Sox9 to activate key astrocyte genes25. This antagonism is reciprocal and highlights the dual roles of these transcription factors in determining fates of glial sub-lineages.

A host of signaling pathways are implicated in promoting the different phases of oligodendrocyte lineage development. PDGFRa, a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) that is expressed in OPCs and is rapidly downregulated during terminal differentiation, is one signaling pathway that plays a role in glioma53,54. Consistent with its expression dynamics, PDGFRa promotes the proliferation and survival of OPCs, with its downregulation serving as a temporal cue that triggers differentiation. Indeed, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that loss of PDGFRa results in precocious differentiation of oligodendrocytes and an overall reduction in their number53,54. Consistent with this, inhibition of downstream RTK pathway components MAPK-ERK impairs the ability of PDGFRa to suppress OPC differentiation55, reinforcing the notion that mitogenic pathways generally suppress differentiation of progenitor populations and thus engender a permissive state for malignant transformation.

Oligodendrocytes: An origin of glioma?

Identifying the cellular substrates that incur driver mutations in key tumor suppressor or oncogene pathways and subsequently give rise to glioma is a major question in the field of glioma biology. This “cell of origin” has been viewed by some as the key to understanding disease pathogenesis. Pioneering work in native mouse models using RCAS-tva based targeting of resident astrocytes or NSCs with oncogenes, revealed that resident NSCs in the brain provide a much more permissive environment for glioma tumorigenesis56. These findings have also been demonstrated in genetic models that utilize deletion of key tumor suppressors in mice57,58.

From these studies, two key features of prospective cells of origin emerged: enhanced proliferative and migratory potential. Given that OPCs are the most proliferative and migratory cell population that resides in the adult brain, and have been estimated to comprise ~10% of the cellular constituency of the adult brain, they possess both the properties of a cell of origin and sufficient cell numbers to provide opportunity for malignant transformation47. Indeed, a series of recent papers have pointed to the OPC as serving as a potential cell of origin in mouse models of glioma. One study took advantage of mosaic analysis with double markers (MADM) to analyze clones exhibiting loss of heterozygosity in tumor suppressor genes NF1 and p53, finding that OPCs make up the majority of proliferative cells within malignant glioma and could serve as the cell of origin59. Similarly, targeted deletion of these key tumor suppressors in OPC populations (via the OPC-specific Cre, NG2-Cre) supported malignant glioma tumorigenesis in genetic models60. Further supporting this notion is transplantation data showing NG2 cells derived from both mouse models and primary human tumors can support glioma tumorigenesis61,62. This experimental evidence, coupled with their normal biological properties, suggests that the origins of malignant glioma may dwell within resident OPCs in the adult brain.

The potential OPC origin of glioma implicates their molecular determinants in glioma tumorigenesis. Over the past decade, several studies have begun deciphering the role of Olig2 in glioma tumorigenesis. Olig2 is expressed in all forms of glioma and is also highly expressed in GSC populations extracted from primary tumors63,64. Functionally, Olig2 cooperates with Ink4a/Arf to engender malignant growth in NSC mouse models, and does so in part by directly suppressing p21 expression63. Moreover, the effects of Olig2 are p53 dependent, where it functions by regulating p53 acetylation, thereby suppressing its capacity to bind DNA and activate transcription65. Recently, in native mouse models of glioma Olig2 has been shown to function through modulation of EGFR signaling, with the loss of Olig2 slowing tumor progression and shifting the type of GBM from proneural to classical (see figure 1)66. This observation provides additional evidence that key regulators of gliogenesis can alter glioma “identity” (see NFIA). Interestingly, studies have shown that phosphorylation regulates the function of Olig2 in glioma, suggesting that pharmacologically targeting this post-translational event may be an avenue for future glioma therapeutics67.

Similar to its Sox-E family counterpart Sox9, the role of Sox10 in glioma formation remains poorly defined. Despite being an oligodendrocyte specific marker, Sox10 demonstrates widespread expression across the full spectrum of glioma subtypes 68. However, functional studies in an RCAS-tva glioma model driven by PDGFR-B show that overexpression of Sox10 mildly promotes tumorigenesis68. As Sox10 collaborates with Olig2 to suppress the generation of astrocytes, it is possible that manipulating its expression may similarly influence glioma “identity”.

PDGF signaling has long been implicated in many aspects of tumor biology69 which, coupled with its essential role in OPC proliferation, makes it an area of intense investigation in glioma. Genomic studies revealed that 11% of GBMs have amplification of PDGFRA, while expression studies in tumors revealed that it demonstrates heterogeneous expression in all grades of glioma70,71. Moreover, several types of mutation variants in the PDGFRA locus have been identified to cause increased receptor tyrosine activity. Together these observations implicate PDGFRA signaling as a key driver of glioma tumorigenesis. Consistent with these features, several studies have shown that manipulation of PDGFRA in mouse glioma models promotes the formation of oligodendroglioma and that complementing loss of p16-ARF can trigger formation of higher-grade oligodendroglioma and malignant glioma72. That manipulation of PDGFRA predominately supports the generation of oligodendroglioma is consistent with its role in OPC development. However, that genetic loss of tumor suppressors can alter the type of tumor generated suggests that the interplay between development and mutation also influences the differentiative state of a given tumors. Finally, PDGFRA functions as an RTK and because RTKs are drivers of several forms of cancer, numerous pharmacological inhibitors have been developed that inhibit their activity. Several of these RTK inhibitors have been tested in clinical trials for malignant glioma and none have effectively impacted survival73, highlighting both the complexity of this disease and dire need for new targeting strategies.

Astrogenesis and glioma heterogeneity

Unlike their cellular counterparts in the CNS, the generation of astrocytes has remained poorly defined at both the cellular and molecular levels. There are several reasons for this: a) paucity of reliable markers, b) difficulty in modeling their complex array of diverse functions, and c) general apathy in the neuroscience community towards this critical topic. Nevertheless, a series of recent papers has begun to unravel the seemingly enigmatic biology surrounding the generation of the most abundant cell type in the CNS.

Astrocyte Lineage Development

Identifying markers that distinguish astrocytes and specifically those that define the phases of lineage progression is essential to improving our understanding of astrocyte development. GFAP has long been heralded as the prototypical marker, even though it is expressed in a minority of astrocytes and is induced at the terminal stages of their differentiation10. Therefore, major efforts have been made to identify more reliable astrocyte markers, to date the most useful of which is Aldh1l174. In terms of stage-specific progression, in the spinal cord it is known that NFIA/Sox9/Glast are induced at E12.5, while GFAP is induced around E18.5 (Figure 4). Whether other genes are specifically induced during these intermediate stages of development remains poorly defined. Recently, two studies sought to define the molecular profiles of these intermediate stages, both finding that astrocytes, like their neuronal and oligodendrocyte counterparts, demonstrate progressive changes in gene expression during lineage development75,76. Among the genes induced during these intermediate stages of astrocyte lineage progression are Asef1 and Nfe2l1, both of which demonstrate astrocyte-restricted expression. While defining these stages at the molecular level is essential, so is understanding the functional properties of intermediate astrocyte precursor populations. Recent studies in both the spinal cord and cortex have shown that astrocyte precursor populations retain proliferative properties, with the RTK BRAF playing a key role in the proliferation of astrocyte precursors in this developmental context77,78 (Figure 4). Interestingly, mutations in BRAF have been associated with low-grade astrocytoma79, suggesting a developmental basis for its function in malignancy. Nevertheless, in both instances, precursor populations that have migrated out of the germinal zones continue to proliferate and divide during restricted developmental windows, with these “pioneering astrocytes” comprising as much as ~50% of resident cortical astrocytes in the adult. Importantly, unlike OPCs, these proliferative events only occur during development and are not retained in resident astrocytes under homeostatic conditions.

Clearly astrocyte precursor populations exist across a spectrum of developmental states, with retention of proliferative capacity during perinatal stages being a recently identified property. Another facet of astrocyte development that has recently garnered a lot of attention is their cellular diversity. Given that astrocytes execute a wide range of diverse functions, it stands to reason that they may also exhibit extensive cellular heterogeneity. Studies in the developing spinal cord have shown that dorsal/ventral patterning mechanisms controlling neuronal subtype diversification also oversee the generation of distinct astrocyte subpopulations80,81. Application of these principles to the developing and adult brain is confounded by a lack of patterning associated mouse tools; however, a series of recent studies have begun to dissect astrocyte heterogeneity in the adult brain. Using comparative expression profiling across distinct brain regions, two recent studies have shown that astrocytes from different brain regions are endowed with distinct molecular and functional properties82,83. In addition, another study identified five distinct astrocyte subpopulations, present across five adult brain regions84. Interestingly, these populations are present in the developing cortex and are endowed with unique proliferative and migratory properties, suggesting a link to the “pioneering astrocyte” phenomenon. Together, these studies reveal the potentially vast reservoir of diverse astrocyte populations that reside in the brain.

At the molecular level, much of what we know about astrocyte development is based on studies linked to the gliogenic switch and the regulation of GFAP expression. Several studies have shown that NFIA and Sox9, key regulators of the gliogenic switch, also regulate GFAP expression22,23. These roles appear to be separate from the gliogenic switch, as expression of both Sox9 and NFIA is retained in mature astrocytes and is associated with key signaling pathways linked to GFAP induction, in both the spinal cord and brain22,23,85,86. Amongst these key pathways is CNTF/gp130/STAT signaling, which plays a central role in the differentiation of astrocytes87,88. Mechanistically, STAT3 cooperates with NFIA to drive GFAP expression, in a Notch dependent manner29. Thus, Notch signaling also appears to play a myriad of roles during gliogenesis. Additional evidence for this comes from studies showing that Sox9 expression in astrocytes requires Notch signaling28. Moreover, the knockdown of Sox9 in Notch1-activated NSCs impaired the generation of astrocytes, suggesting that Notch’s role in astrocyte development is dependent on its promotion of Sox989. Moving forward it will be important to delineate the mechanisms that uncouple the functions of these key factors in the gliogenic switch from their roles in astrocyte differentiation. Towards this, recent studies have shown that the transcription factor Zbtb20 promotes astrocyte development and cooperates with NFIA and Sox9, but does not directly regulate GFAP expression, suggesting that it may function during these intermediate phases of development90.

Astrocytes and heterogeneity in glioma

One cardinal feature of glioma is the immense cellular diversity of the bulk tumor, which is largely comprised of pathological analogs of the normal tissue. Given the abundance of astrocytes in the adult brain, coupled with the astro-glial like histopathological features of malignant glioma it is likely that astrocytes and their derivatives comprise a significant portion of this heterogeneous cellular constituency.

Given these links, a question that emerges is whether astrocytes can also serve as a cell of origin for GBM or astrocytoma. Several studies have targeted astrocytes using GFAP-associated tools in mouse models (RCAS-tva and conditional mouse genetics) and found that manipulating drivers in resident astrocytes in the adult brain does not result in highly penetrant glioma tumorigenesis56,57. The likely reason for the low penetrance in targeted astrocytes is that they are post-mitotic and transformation events that occur within them would have to trigger a series of de-differentiation events to generate the cellular constituency of glioma. Based on these studies, it would seem that triggering these de-differentiation events in astrocytes is a relatively rare occurrence. However, these studies rely on GFAP expression for gene manipulation and thus likely do not comprehensively target all astrocytes. Thus, it is possible that some astrocytes are more prone to malignant transformation or triggering dedifferentiation than others. Examples for this phenomenon come from other pathological states in the CNS, where recent studies have shown that after brain injury subsets of astrocytes can convert to neurons91. Given that these select astrocyte populations are endowed with latent neurogenic capacity, it is possible these same populations may also be more susceptible de-differentiation and subsequent malignant transformation. Together, these observations further highlight the need to generate additional mouse tools for selective targeting of astrocyte populations in the adult brain.

These observations raise the question whether we can use the presence of diverse astrocyte subpopulations in the brain to explain cellular heterogeneity of malignant glioma. Regional diversity is one major consideration, as glioma can emerge across numerous brain regions and accordingly tumors derived from these regions may exhibit the molecular features of these region specific astrocytes. Another consideration is local diversity in the form of astrocyte subpopulations within specific brain regions. The same study that identified 5 astrocyte subpopulations in the adult brain went on to show that 4 of these populations are present in primary human glioma and multiple mouse models of glioma84. At the molecular level, these glioma subpopulations share analogous gene expression signatures with their astrocyte counterparts, suggesting that cellular heterogeneity present within glioma may be partially derived from these astrocyte subpopulations. Finally, given that glioma is also comprised of cells exhibiting undifferentiated histopathological features, it is likely that part of this cellular heterogeneity is derived from intermediate precursor populations that reside along the course of astrocyte lineage trajectory77,78. Another method for discriminating cellular diversity is single cell RNA-sequencing. Several studies have used this approach for GBM, finding diverse gene expression profiles that infer the presence of diverse cell populations that exist along a spectrum of differentiated states92,93. It will be important to discern how these prospective malignant populations align with their normal counterparts, as it may give insights into how specific lineages arrive at their malignant destinations in GBM. For example, one tantalizing possibility is that each of these unique astrocyte subpopulations is endowed with differential de-differentiation capacity or responses to specific oncogenic stimuli. This scenario would suggest a combinatorial code of genetic mutation and glial cellular context that may explain, in part, the prospective origins of different forms of glioma.

At the molecular level, because GFAP is also highly expressed in glioma, its regulatory mechanisms contribute to tumorigenesis. Among these mechanisms, Stat3 is a key regulator of GFAP expression that plays key roles in oncogenesis in other systems. In glioma, a myriad of studies in human derived cell glioma cell line and GSC systems have shown that STAT3 functions to promote glioma tumorigenesis94. Because STAT3 serves as a key signaling node for numerous pathways, it interfaces with several systems associated with glioma. Studies in mouse models have shown that loss of STAT3 in astrocytes suppresses growth, however, when combined with loss of PTEN, STAT3 function becomes oncogenic95. Thus, much like Notch-RBPJ, STAT3 function is also context dependent. STAT3 has also been linked to EGFR signaling, where EGFR can activate STAT3 and it complexes with mutant, activated forms of EGFR-vIII to drive tumorigenesis96. This relationship is part of a feed-forward mechanism whereby STAT3 regulates both iNOS and OSMR expression, which subsequently complexes with EGFR and facilitates the EGFR-STAT3 interaction and tumorigenesis97. Given its ubiquity across malignancies, significant efforts have been made to develop therapeutics that target STAT3. Current approaches involve targeting the upstream regulators JAK1/2 or activated STAT3 itself98,99. In both cases, the broad roles of these factors in numerous core cellular processes limit their efficacy, moreover current STAT3 inhibitors may have off target effects. These limitations, coupled with the central role of STAT3 in glioma, illustrate the need to develop new therapeutics for this pathway.

Blazing a Gliogenic Path

The rationale for studying developmental gliogenesis in the context of glioma is the hope that understanding how to make glial cells will inform how glioma is generated and reveal new approaches for curbing glioma growth. Viewing the problem of glial malignancy from the developmental perspective and the concept of differentiation therapy emerges, where the manipulation of defined developmental factors influences the production of tumor cells. This paradigm has been exploited for hematopoietic malignancies, where treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) with retinoic acid and arsenic results in differentiation of malignant progenitors and disease remission100. While promising, these implementing parallel approaches in solid tumors have proven challenging. For glioma, the first steps of this journey will be identifying pathways that influence tumor subtype differentiation in native and human cell line models. Indeed, studies with the glial transcription factors, NFIA and Olig2, in native mouse models of glioma, have shown that manipulating these factors can influence the type of glioma generated (Figure 3). These observations highlight the need to more carefully examine how glial development factors influence molecular and cellular identities in native models of glioma, as targeting these pathways may direct a form of differentiation therapy.

In the era of genomics, we on the verge of cataloging every mutation present in glioma. While this is an impressive feat, new therapeutics for this malicious disease will only result from acting on this information. Viewing these questions through the lens of glial development, two critical areas of investigation emerge. First, is decoding the cellular correlates of genetic mutation by understanding how specific glial cellular contexts interface with key genetic drivers of glioma. This will require identifying the various heterogeneous cell populations that comprise the normal brain, primary glioma tumors, and deciphering how genetic drivers of this disease create malignant populations from normal glial substrates. Deconvolution of this potentially immense cellular diversity begins with an understanding of normal glial diversity, both mature and immature populations and identifying analogous populations in glioma models. Towards this, established methodologies harnessing single cell approaches, in combination with direct functional screening of inferred cellular diversity will be critical. Second, is acquiring an understanding of the molecular interface between glial developmental factors and key drivers of tumorigenesis to influence cell fate and tumorigenesis. Given the potential interdependence between these factors during tumorigenesis (see STAT3-PTEN), these relationships will likely guide how differentiation therapies are implemented. Moving forward it will be critical to merge these vast genomic data sets with the developmental and cellular context in which they function.

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Gillespie for editing and reviewing this manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS071153 to BD and K01CA190235 and 5-T32HL092332-08 to SG), Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas (RP150334 and RP160192 to BD).

References

- 1.Hanahan D & Weinberg RA Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013S0092-8674(11)00127-9 [pii] (2011).** The expanded version of the canonical primer on cancer biology.

- 2.Wainwright EN & Scaffidi P Epigenetics and Cancer Stem Cells: Unleashing, Hijacking, and Restricting Cellular Plasticity. Trends Cancer 3, 372–386, doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.04.004 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takebe N et al. Targeting Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 12, 445–464, doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.61 (2015).** A comprehensive review of current pipeline therapies targeting developmental pathway components for glioma treatment.

- 4.Joruiz SM & Bourdon JC p53 Isoforms: Key Regulators of the Cell Fate Decision. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 6, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a026039 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Veleva-Rotse BO & Barnes AP Brain patterning perturbations following PTEN loss. Front Mol Neurosci 7, 35, doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00035 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molofsky AV et al. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature 443, 448–452, doi: 10.1038/nature05091 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez-Martin M & Ferrando A The NOTCH1-MYC highway toward T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 129, 1124–1133, doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-692582 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok TS Personalized medicine in lung cancer: what we need to know. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8, 661–668, doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.126 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birey F, Kokkosis AG & Aguirre A Oligodendroglia-lineage cells in brain plasticity, homeostasis and psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol 47, 93–103, doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.09.016 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molofsky AV & Deneen B Astrocyte development: A Guide for the Perplexed. Glia 63, 1320–1329, doi: 10.1002/glia.22836 (2015).** A thorough and approachable description of astrocyte development.

- 11.Louis DN et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131, 803–820, doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1 [pii] (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhaak RG et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 17, 98–110, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.020S1535-6108(09)00432-2 [pii] (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennan CW et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155, 462–477, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034S0092-8674(13)01208-7 [pii] (2013).** A characterization of adult GBM subtypes based on relevant patterns of somatic mutations.

- 14.Baker SJ, Ellison DW & Gutmann DH Pediatric gliomas as neurodevelopmental disorders. Glia 64, 879–895, doi: 10.1002/glia.22945 (2016).** A more thorough discussion of the unique properties of pediatric gliomas, how they differ from adult gliomas, and the genetic basis for their relationship to development.

- 15.Jones C & Baker SJ Unique genetic and epigenetic mechanisms driving paediatric diffuse high-grade glioma. Nat Rev Cancer 14, doi: 10.1038/nrc3811 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackay A et al. Integrated Molecular Meta-Analysis of 1,000 Pediatric High-Grade and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Cancer Cell 32, 520–537 e525, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.08.017 (2017).** A thorough and modern classification of pediatric glioma subtypes based on patient genomic alterations.

- 17.Singh SK et al. Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature 432, 396–401, doi:nature03128 [pii] 10.1038/nature03128 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu S, Wu Y & Capecchi MR Motoneurons and oligodendrocytes are sequentially generated from neural stem cells but do not appear to share common lineage-restricted progenitors in vivo. Development 133, 581–590, doi: 10.1242/dev.02236 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masahira N et al. Olig2-positive progenitors in the embryonic spinal cord give rise not only to motoneurons and oligodendrocytes, but also to a subset of astrocytes and ependymal cells. Dev Biol 293, 358–369, doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.029 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravanelli AM & Appel B Motor neurons and oligodendrocytes arise from distinct cell lineages by progenitor recruitment. Genes Dev 29, 2504–2515, doi: 10.1101/gad.271312.115 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukouyama YS et al. Olig2+ neuroepithelial motoneuron progenitors are not multipotent stem cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 1551–1556, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510658103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stolt CC et al. The Sox9 transcription factor determines glial fate choice in the developing spinal cord. Genes Dev 17, 1677–1689, doi: 10.1101/gad.259003 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deneen B et al. The transcription factor NFIA controls the onset of gliogenesis in the developing spinal cord. Neuron 52, 953–968, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.019 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang P et al. Sox9 and NFIA coordinate a transcriptional regulatory cascade during the initiation of gliogenesis. Neuron 74, 79–94, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.024 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glasgow SM et al. Glia-specific enhancers and chromatin structure regulate NFIA expression and glioma tumorigenesis. Nat Neurosci 20, 1520–1528, doi: 10.1038/nn.4638 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatakeyama J et al. Hes genes regulate size, shape and histogenesis of the nervous system by control of the timing of neural stem cell differentiation. Development 131, 5539–5550, doi: 10.1242/dev.01436 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park HC & Appel B Delta-Notch signaling regulates oligodendrocyte specification. Development 130, 3747–3755 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor MK, Yeager K & Morrison SJ Physiological Notch signaling promotes gliogenesis in the developing peripheral and central nervous systems. Development 134, 2435–2447, doi: 10.1242/dev.005520 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namihira M et al. Committed neuronal precursors confer astrocytic potential on residual neural precursor cells. Dev Cell 16, 245–255, doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.014 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suva ML et al. Reconstructing and reprogramming the tumor-propagating potential of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cell 157, 580–594, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.030S0092-8674(14)00229-3 [pii] (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lan X et al. Fate mapping of human glioblastoma reveals an invariant stem cell hierarchy. Nature 549, 227–232, doi: 10.1038/nature23666 (2017).** Elegantly shows that intratumoral GBM heterogeneity arises from hierarchical fate progression of GSCs, similar to that of developmental glial stem cells.

- 32.Glasgow SM et al. The miR-223/Nuclear Factor I-A Axis Regulates Glial Precursor Proliferation and Tumorigenesis in the CNS. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 33, 13560–13568, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0321-13.2013 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song HR et al. Nuclear factor IA is expressed in astrocytomas and is associated with improved survival. Neuro-oncology 12, 122–132, doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop044 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasgow SM et al. Mutual antagonism between Sox10 and NFIA regulates diversification of glial lineages and glioma subtypes. Nat Neurosci 17, 1322–1329, doi: 10.1038/nn.3790nn.3790 [pii] (2014).** This paper draws parallels between glial development and glioma tumorigenesis through misexpression of glial specific transcription factors Sox10 and NFIA.

- 35.Schlierf B et al. Expression of SoxE and SoxD genes in human gliomas. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 33, 621–630, doi:NAN881 [pii] 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00881.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H et al. SOX9 Overexpression Promotes Glioma Metastasis via Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling. Cell Biochem Biophys 73, 205–212, doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0647-z (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swartling FJ et al. Distinct neural stem cell populations give rise to disparate brain tumors in response to N-MYC. Cancer Cell 21, 601–613, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teodorczyk M & Schmidt MH Notching on Cancer's Door: Notch Signaling in Brain Tumors. Front Oncol 4, 341, doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00341 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giachino C et al. A Tumor Suppressor Function for Notch Signaling in Forebrain Tumor Subtypes. Cancer Cell 28, 730–742, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.008 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie Q et al. RBPJ maintains brain tumor-initiating cells through CDK9-mediated transcriptional elongation. J Clin Invest 126, 2757–2772, doi: 10.1172/JCI86114 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liau BB et al. Adaptive Chromatin Remodeling Drives Glioblastoma Stem Cell Plasticity and Drug Tolerance. Cell Stem Cell 20, 233–246 e237, doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.003 (2017).** Highlights mechanisms through which GSCs reutilize developmental pathways and epigenetic programs to transition between proliferative states and plasticity.

- 42.Fancy SP, Chan JR, Baranzini SE, Franklin RJ & Rowitch DH Myelin regeneration: a recapitulation of development? Annu Rev Neurosci 34, 21–43, doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113629 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emery B & Lu QR Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation of Oligodendrocyte Development and Myelination in the Central Nervous System. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7, a020461, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020461 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergles DE & Richardson WD Oligodendrocyte Development and Plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 8, a020453, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020453 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dimou L & Gallo V NG2-glia and their functions in the central nervous system. Glia 63, 1429–1451, doi: 10.1002/glia.22859 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu X et al. Age-dependent fate and lineage restriction of single NG2 cells. Development 138, 745–753, doi: 10.1242/dev.047951 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishiyama A, Boshans L, Goncalves CM, Wegrzyn J & Patel KD Lineage, fate, and fate potential of NG2-glia. Brain Res 1638, 116–128, doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.08.013 (2016).** An extensive mapping of the potential and fate of NG2 cells, a proposed cell of origin for glioma.

- 48.Vigano F & Dimou L The heterogeneous nature of NG2-glia. Brain Res 1638, 129–137, doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.09.012 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu QR et al. Sonic hedgehog--regulated oligodendrocyte lineage genes encoding bHLH proteins in the mammalian central nervous system. Neuron 25, 317–329, doi:S0896-6273(00)80897-1 [pii] (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Q & Anderson DJ The bHLH transcription factors OLIG2 and OLIG1 couple neuronal and glial subtype specification. Cell 109, 61–73, doi:S0092867402006773 [pii] (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Britsch S et al. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev 15, 66–78 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Finzsch M, Stolt CC, Lommes P & Wegner M Sox9 and Sox10 influence survival and migration of oligodendrocyte precursors in the spinal cord by regulating PDGF receptor alpha expression. Development 135, 637–646, doi: 10.1242/dev.010454dev.010454 [pii] (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raff MC, Lillien LE, Richardson WD, Burne JF & Noble MD Platelet-derived growth factor from astrocytes drives the clock that times oligodendrocyte development in culture. Nature 333, 562–565, doi: 10.1038/333562a0 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fruttiger M et al. Defective oligodendrocyte development and severe hypomyelination in PDGF-A knockout mice. Development 126, 457–467 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chew LJ, Coley W, Cheng Y & Gallo V Mechanisms of regulation of oligodendrocyte development by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30, 11011–11027, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2546-10.2010 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holland EC et al. Combined activation of Ras and Akt in neural progenitors induces glioblastoma formation in mice. Nat Genet 25, 55–57, doi: 10.1038/75596 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alcantara Llaguno S et al. Malignant astrocytomas originate from neural stem/progenitor cells in a somatic tumor suppressor mouse model. Cancer Cell 15, 45–56, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.12.006 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hambardzumyan D, Parada LF, Holland EC & Charest A Genetic modeling of gliomas in mice: new tools to tackle old problems. Glia 59, 1155–1168, doi: 10.1002/glia.21142 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu C et al. Mosaic analysis with double markers reveals tumor cell of origin in glioma. Cell 146, 209–221, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.014S0092-8674(11)00656-8 [pii] (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alcantara Llaguno SR et al. Adult Lineage-Restricted CNS Progenitors Specify Distinct Glioblastoma Subtypes. Cancer Cell 28, 429–440, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.007 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Persson AI et al. Non-stem cell origin for oligodendroglioma. Cancer Cell 18, 669–682, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.033 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yadavilli S et al. The emerging role of NG2 in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Oncotarget 6, 12141–12155, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3716 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ligon KL et al. Olig2-regulated lineage-restricted pathway controls replication competence in neural stem cells and malignant glioma. Neuron 53, 503–517, doi:S0896-6273(07)00029-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.009 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ligon KL et al. The oligodendroglial lineage marker OLIG2 is universally expressed in diffuse gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 63, 499–509 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mehta S et al. The central nervous system-restricted transcription factor Olig2 opposes p53 responses to genotoxic damage in neural progenitors and malignant glioma. Cancer Cell 19, 359–371, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.035S1535-6108(11)00047-X [pii] (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu F et al. Olig2-Dependent Reciprocal Shift in PDGF and EGF Receptor Signaling Regulates Tumor Phenotype and Mitotic Growth in Malignant Glioma. Cancer Cell 29, 669–683, doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.03.027 (2016).** An excellent utilization of genetic tools to modulate regulators of developmental gliogenesis during glioma tumorigenesis to affect glioma subtype identity.

- 67.Zhou J et al. A Sequentially Priming Phosphorylation Cascade Activates the Gliomagenic Transcription Factor Olig2. Cell Rep 18, 3167–3177, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.003 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ferletta M, Uhrbom L, Olofsson T, Ponten F & Westermark B Sox10 has a broad expression pattern in gliomas and enhances platelet-derived growth factor-B--induced gliomagenesis. Mol Cancer Res 5, 891–897, doi:5/9/891 [pii] 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0113 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Heldin CH Targeting the PDGF signaling pathway in tumor treatment. Cell Commun Signal 11, 97, doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-97 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phillips JJ et al. PDGFRA amplification is common in pediatric and adult high-grade astrocytomas and identifies a poor prognostic group in IDH1 mutant glioblastoma. Brain Pathol 23, 565–573, doi: 10.1111/bpa.12043 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature 455, 1061–1068, doi: 10.1038/nature07385nature07385 [pii] (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dai C et al. PDGF autocrine stimulation dedifferentiates cultured astrocytes and induces oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas from neural progenitors and astrocytes in vivo. Genes Dev 15, 1913–1925, doi: 10.1101/gad.903001 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mellinghoff IK, Schultz N, Mischel PS & Cloughesy TF Will kinase inhibitors make it as glioblastoma drugs? Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 355, 135–169, doi: 10.1007/82_2011_178 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cahoy JD et al. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 28, 264–278, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008 (2008).** A valuable database of transcriptome data from glial development that may be useful to inform glioma tumorigenesis studies.

- 75.Molofsky AV et al. Expression profiling of Aldh1l1-precursors in the developing spinal cord reveals glial lineage-specific genes and direct Sox9-Nfe2l1 interactions. Glia 61, 1518–1532, doi: 10.1002/glia.22538 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chaboub LS et al. Temporal Profiling of Astrocyte Precursors Reveals Parallel Roles for Asef during Development and after Injury. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 36, 11904–11917, doi:36/47/11904 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1658-16.2016 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tien AC et al. Regulated temporal-spatial astrocyte precursor cell proliferation involves BRAF signalling in mammalian spinal cord. Development 139, 2477–2487, doi: 10.1242/dev.077214 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ge WP, Miyawaki A, Gage FH, Jan YN & Jan LY Local generation of glia is a major astrocyte source in postnatal cortex. Nature 484, 376–380, doi: 10.1038/nature10959 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jones DT et al. Recurrent somatic alterations of FGFR1 and NTRK2 in pilocytic astrocytoma. Nature genetics 45, 927–932, doi: 10.1038/ng.2682 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tsai HH et al. Regional astrocyte allocation regulates CNS synaptogenesis and repair. Science 337, 358–362, doi: 10.1126/science.1222381 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hochstim C, Deneen B, Lukaszewicz A, Zhou Q & Anderson DJ Identification of positionally distinct astrocyte subtypes whose identities are specified by a homeodomain code. Cell 133, 510–522, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.046 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chai H et al. Neural Circuit-Specialized Astrocytes: Transcriptomic, Proteomic, Morphological, and Functional Evidence. Neuron 95, 531–549 e539, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.029 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Morel L et al. Molecular and Functional Properties of Regional Astrocytes in the Adult Brain. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 37, 8706–8717, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3956-16.2017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lin JCC et al. Identification of diverse astrocyte populations and their malignant analogs. Nat Neurosci 20, 396–405, doi: 10.1038/nn.4493nn.4493 [pii] (2017).** This study found that molecularly distinct astrocyte populations isolated from healthy brain tissue have analogous populations in glioma tumors.

- 85.das Neves L et al. Disruption of the murine nuclear factor I-A gene (Nfia) results in perinatal lethality, hydrocephalus, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 11946–11951 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sun W et al. SOX9 Is an Astrocyte-Specific Nuclear Marker in the Adult Brain Outside the Neurogenic Regions. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 37, 4493–4507, doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3199-16.2017 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bonni A et al. Regulation of gliogenesis in the central nervous system by the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Science 278, 477–483 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barnabe-Heider F et al. Evidence that embryonic neurons regulate the onset of cortical gliogenesis via cardiotrophin-1. Neuron 48, 253–265, doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.037 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Martini S et al. A critical role for Sox9 in notch-induced astrogliogenesis and stem cell maintenance. Stem Cells 31, 741–751, doi: 10.1002/stem.1320 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nagao M, Ogata T, Sawada Y & Gotoh Y Zbtb20 promotes astrocytogenesis during neocortical development. Nat Commun 7, 11102, doi: 10.1038/ncomms11102ncomms11102 [pii] (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Magnusson JP et al. A latent neurogenic program in astrocytes regulated by Notch signaling in the mouse. Science 346, 237–241, doi: 10.1126/science.346.6206.237 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Darmanis S et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis of Infiltrating Neoplastic Cells at the Migrating Front of Human Glioblastoma. Cell Rep 21, 1399–1410, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.030 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patel AP et al. Single-cell RNA-seq highlights intratumoral heterogeneity in primary glioblastoma. Science 344, 1396–1401, doi: 10.1126/science.1254257 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.de la Iglesia N, Puram SV & Bonni A STAT3 regulation of glioblastoma pathogenesis. Curr Mol Med 9, 580–590 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de la Iglesia N et al. Identification of a PTEN-regulated STAT3 brain tumor suppressor pathway. Genes Dev 22, 449–462, doi: 10.1101/gad.1606508gad.1606508 [pii] (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fan QW et al. EGFR phosphorylates tumor-derived EGFRvIII driving STAT3/5 and progression in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 24, 438–449, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.004 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jahani-Asl A et al. Control of glioblastoma tumorigenesis by feed-forward cytokine signaling. Nat Neurosci 19, 798–806, doi: 10.1038/nn.4295 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jackson C, Ruzevick J, Amin AG & Lim M Potential role for STAT3 inhibitors in glioblastoma. Neurosurg Clin N Am 23, 379–389, doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2012.04.002 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Furtek SL, Backos DS, Matheson CJ & Reigan P Strategies and Approaches of Targeting STAT3 for Cancer Treatment. ACS Chem Biol 11, 308–318, doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00945 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.de The H Differentiation therapy revisited. Nat Rev Cancer 18, 117–127, doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.103 (2018).** An interesting opinion on the ways differentiation therapies have been used to treat certain tumors and how these treatments may be improved to treat other malignancies.

- 101.Ostrom QT et al. The epidemiology of glioma in adults: a "state of the science" review. Neuro-oncology 16, 896–913, doi:nou087 [pii] 10.1093/neuonc/nou087 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]