Abstract

Objective:

Knee arthroplasty (KA) is an effective surgical procedure. However, clinical studies suggest that a considerable number of patients continue to experience substantial pain and functional loss following surgical recovery. We aimed to estimate pain and function outcome trajectory types for persons undergoing KA, and to determine the relationship between pain and function trajectory types, and pre-surgery predictors of trajectory types.

Design:

Participants were 384 patients who took part in the Knee Arthroplasty Skills Training randomized clinical trial. Pain and function were assessed at 2-week pre- and 2-, 6-, and 12-months post-surgery. Piecewise latent class growth models were used to estimate pain and function trajectories. Pre-surgery variables were used to predict trajectory types.

Results:

There was strong evidence for two trajectory types, labeled as good and poor, for both WOMAC Pain and Function scores. Model estimated rates of the poor trajectory type were 18% for pain and function. Dumenci’s latent kappa between pain and function trajectory types was 0.71 (95% CI: 0.61 – 0.80). Pain catastrophizing and number of painful body regions were significant predictors of poor pain and function outcomes. Outcome-specific predictors included low income for poor pain and baseline pain and younger age for poor function.

Conclusions:

Among adults undergoing KA, approximately one-fifth continue to have persistent pain, poor function, or both. Although the poor pain and function trajectory types tend to go together within persons, a significant number experience either poor pain or function but not both, suggesting heterogeneity among persons who do not fully benefit from KA.

Knee arthroplasty (KA) is a highly effective surgical procedure for approximately 80% of patients. However, up to 20% report persistent pain and/or substantial functional deficits in the year following surgery1–8. Because pain relief and functional improvement are the primary reasons patients undergo KA9, persistent pain or functional deficits can lead to patient dissatisfaction following surgical recovery4,10.

Given the growing utilization, surgical risks and high costs of KA, there is substantial interest in identifying persons who are at risk for poor outcomes following surgery11. Two approaches have generally been used to classify good versus poor outcomes in this context; cross-sectional assessment and minimally clinically important difference (MCID) approaches. Cross-sectional assessments require patients to indicate the severity of their pain or functional deficit at a specific time point following surgery. A limitation of cross sectional approaches to categorize outcome is that they apply arbitrary cut points to classify patients into outcome subgroups. For example, Beswick et al defined favorable pain outcome as no pain or mild pain while unfavorable pain outcome was defined as moderate or severe pain reported at the time point of interest8.

The MCID approach requires calculation of the difference between pre-operative and postoperative scores to determine if the change meets or exceeds the pre-established MCID for the measure of interest8. For the MCID approach, different methods are used for both the calculation of MCID and for the establishment of MCID thresholds. For example, one MCID may require patients to report at least moderate pain relief while another may require at least minor pain relief to meet the MCID.

Arbitrary definitions for good versus poor outcome create uncertainty when comparing across studies or across outcome measures, because definitions vary and are not scientifically grounded. Mild pain with the WOMAC Pain scale at a specific time point, for example, may reflect a different outcome as compared to mild pain based on a verbal pain rating. Variation in both the methods for measuring pain and function and the interpretation of the scores obtained with these measures preclude sound determinations of who truly benefits from KA and who may require additional treatment3.

One solution to the arbitrary nature and lack of clarity in judging categories of outcome is to rely on a statistical modeling-based approach to determine outcome categories. For example, one study used latent class analysis, a model-based approach for determining trajectories of good versus poor pain and function outcomes following knee replacement12. However, this study used the 1989 version of t6he Pain and Function subscales from Knee Society Score13, a scale with questionable reliability and validity14,15 and, in our experience, a scale that is rarely used in current practice.

Given these considerations, the primary purpose of our study was to identify clinically informative trajectories of pain and function recovery in persons following KA. We hypothesized that pain and function trajectory-based classification of treatment outcomes would yield approximately 20% poor outcomes as reported in the literature. We also estimated the chance-corrected agreement between pain and function outcome types to determine the extent to which persons have the same outcome for both pain and function. We hypothesized that the chance-corrected agreement would be relatively high between pain- and function-based trajectory groupings. Our third purpose was to identify predictors for the poor pain and function trajectory subgroups. We hypothesized that differing sets of pre-surgical variables would predict pain versus function group membership16.

METHODS

Settings

The data for the current analyses were based on the findings from a three-arm National Institutes of Health funded randomized clinical trial (UM1AR062800) conducted at five university-based sites (Virginia Commonwealth University, Duke University, New York University Medical Center, Southern Illinois University, and Wake Forest University). The three treatment arms were pain coping skills training, arthritis education and usual care. For more detail on the trial, please see the published protocol17 and the primary study results18. The institutional review boards from all sites approved the study.

Participants

Patients screened for potential participation were 45 years or older and diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis as confirmed by the treating surgeon. All had a KA scheduled 1–8 weeks after consent, scored 16 or greater on the Pain Catastrophizing Scale19, and read and spoke English. Exclusion criteria were a scheduled revision surgery, hip or KA within 6 months of the surgery of interest, a self-reported diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), scheduled for bilateral KA, planned to have hip or KA surgery within 6 months after the KA of interest, scored 20 or greater on the Personal Health Questionnaire depression scale (PHQ-8) indicating severe clinical depression20, or scored 2 or less on a cognitive screener indicating cognitive deficit21. Eligible individuals who agreed to participate signed a written consent form and provided all baseline data. Participants were compensated $50 at the baseline visit.

Outcome Measures

The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) Pain and Physical Function Scales, 3.1 Likert version, were used.. The Pain scale ranges from 0 (no pain with activity) to 20 (extreme pain with activity) and the Function scale ranges from 0 to 68 with higher scores indicating functional problems. Extensive literature supports reliability and validity of the WOMAC among KA patients22.

Baseline Predictors of Outcome Type

To determine if select baseline variables predicted outcome trajectory type (i.e., good or poor) for WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function scores, we relied on research evidence12,23,24 to guide variable selection. We included previously validated measures of baseline WOMAC Pain or Function scores, depending on the model, arthritis self-efficacy (scored from 0 to 80 with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy)25, pain catastrophizing (scored from 0 to 60 with higher scores equating to higher catastrophizing)19, painful body regions (scored from 0 to 16 with higher scores indicating a greater number of painful body regions)26, depressive symptoms, age, sex, income, BMI, comorbidity, and opioid use. Race/ethnicity was dichotomized to black subjects or all other subjects. BMI was recorded as kg/m2 based on baseline data obtained at hospital admission. We used the Charlson comorbidity index to quantify extent of comorbidity27. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) was used to quantify extent of depressive symptoms20. The PHQ-8 is scored from 0 to 24 with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Statistical Analysis

Exploratory piecewise latent class growth analysis (P-LCGA) was used to estimate the trajectory types, separately for WOMAC Pain and Function scores, measured at four occasions: 2-week pre- and 2-, 6-, and 12-months post-surgery. The first piece of the trajectory was estimated to capture the short-term impact of the surgical procedure (up to 2 months post-surgery) and the second piece to capture the longer-term effect up to one year. Prior research has shown that the majority of improvement from KA occurs within two months of surgery with gradual improvement thereafter28–30. Two- to five-class solutions were examined. Model fit information (likelihood ratio test, entropy, AIC, BIC, sample-size adjusted BIC, Root mean square error of approximation, comparative fit index, Tucker-Lewis index), class separation, and the estimated prevalence of cluster types (i.e., unconditional probabilities) were used to determine the optimal number of classes31,32. Dumenci’s latent Kappa coefficient33(Kl) was used to estimate the chance-corrected agreement between the discrete pain and function trajectory classes using the unconditional probability parameters estimated from the P-LCGA. Once the optimal P-LCGA solution was determined, the three-step procedure was used to examine predictors of class membership34. In all analyses, the Huber-White estimator was used to adjust model fit indices and standard errors due to clustered sampling of patients within surgeons. The average cluster size was 12. Full information maximum likelihood method was used for handling missing data. Analyses were conducted using Mplus (v.8).

RESULTS

From January, 2013 to June, 2016, 4,043 patients were considered for screening. Of these, 551 declined to participate in screening, 917 did not respond to screening requests, and 1,976 did not meet one or more inclusion criteria. Of the 599 that met all criteria, 402 provided consent. Of 402 participants who consented to participate, 18 had their surgery either canceled or delayed for medical reasons and did not have knee surgery during the study period. A total of 367 underwent total KA and n = 17 had unicompartmental KA. A total of 32 surgeons performed KAs with the number of patients ranging from 1 to 54 per surgeon.

Four sites each consented between 94 and 108 participants while one site consented 5 participants. Overall follow-up response rates were 86% (n = 347) at two months, 83% (n = 335) at six months and 86% (n = 346) at 12 months. Among participants who had KA surgery (n = 384), 12-month follow-up was 90%.

Baseline characteristics were similar across treatment groups (Table 1). Median knee pain duration was 6 years and the mean (SD) baseline WOMAC Pain score was 11.4 (3.4) while the mean (SD) baseline WOMAC Function score was 37.2 (11.6). Main trial findings indicated no significant differences among the three study arms (Pain Coping Skills training, Arthritis Education or Usual Care) for WOMAC Pain, WOMAC Function and all other secondary outcomes over the study period18. We therefore combined data from the three treatment groups for the current analyses.

Table 1.

Preoperative sample characteristics (n = 384)

| Baseline Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 63.2 | (8.0) |

| Sex (female), N (%) | 257 | (67) |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2), mean (SD) | 32.3 | (6.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, N, (%) | ||

| White | 240 | (63) |

| African American | 135 | (35) |

| Hispanic | 13 | (3) |

| Asian | 8 | (2) |

| Declineda | 3 | (1) |

| Current Income, N (%) | ||

| < $10,000 | 35 | (9) |

| $10,000 to $24,999 | 78 | (20) |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 88 | (23) |

| $50,000 to $99,999 | 93 | (24) |

| $100,000 or > | 53 | (14) |

| Declined | 37 | (10) |

| Current work status, N (%) | ||

| Employed | 128 | (33) |

| Not working in part due to health | 94 | (25) |

| problems | ||

| Not working for other reasons | 161 | (42) |

| Declined | 1 | (0.2) |

| Education, N (%) | ||

| Less than high school | 22 | (6) |

| High school graduate | 86 | (22) |

| Some college | 101 | (26) |

| College degree or higher | 175 | (46) |

| Marital Status, N (%) | ||

| Married | 193 | (50) |

| Divorced | 71 | (19) |

| Never Married | 46 | (12) |

| Widowed | 47 | (12) |

| Separated | 18 | (5) |

| Member of an unmarried couple | 7 | (2) |

| Declined | 2 | (1) |

| Current smoker (yes) N, (%) | 46 | (12) |

| Modified Charlson comorbidity, mean (SD)b | 8.6 | (4.1) |

| Knee pain duration, median years (IQR) | 6 | (3–15) |

| Opioid use at baseline, N, (%) | 120 | (31) |

| Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (yes) N, (%) | 17 | (4) |

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8), mean (SD)c | 5.9 | (4.9) |

| Generalized Anxiety Scale (GAD-7), mean (SD)d | 5.4 | (4.9) |

| Arthritis Self-efficacy Scale, mean (SD)e | 49.3 | (17.7) |

| WOMAC Pain Scale, mean (SD)f | 11.4 | (3.4) |

| WOMAC Physical Function, mean (SD)g | 37.1 | (11.5) |

| Numeric pain rating, mean (SD)g | 6.1 | (1.9) |

| Short Physical Performance Battery, mean (SD)h | 9.3 | (2.9) |

| Six Minute Walk Test (meters), mean (SD) | 356 | (103) |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale, mean (SD)i | 30.0 | (9.3) |

Abbreviations: WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

Race/ethnicity category of “Other” indicates, other (not specified), or missing. Sum may equal > 100% because of multiple categories.

Modified Charlson Comorbidity score range is 0 to 45. Higher scores equate to greater comorbidity burden.

PHQ-8 score range is 0 to 24. Higher scores equate to more depressive symptoms.

GAD-7 score range is 0 to 21. Higher scores equate to more anxiety.

Arthritis Self Efficacy Scale score range is 0 to 80. Higher scores equate to more self-efficacy.

WOMAC Pain Scale score range is 0 to 20. Higher scores equate to more function limiting pain.

WOMAC Function scale range is 0 to 68. Higher scores equate to more difficulty with functional activities.

Short Physical Performance Battery score range is 0 to 12. Higher scores equate to better performance.

Pain Catastrophizing Scale range is 0 to 52. Higher scores equate to more pain catastrophizing.

For both WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function scores, three- four- and five-class solutions yielded one or more trajectory types representing less than 2% of the population, were judged as not clinically meaningful, and subsequently dismissed as models underlying the data. As an indicator of classification quality (i.e., class or subgroup separation), entropy was high (.89 for pain and .87 for function) for the two-class solution, indicating that this model adequately represents the four-wave longitudinal data for both WOMAC Pain and Function scores.

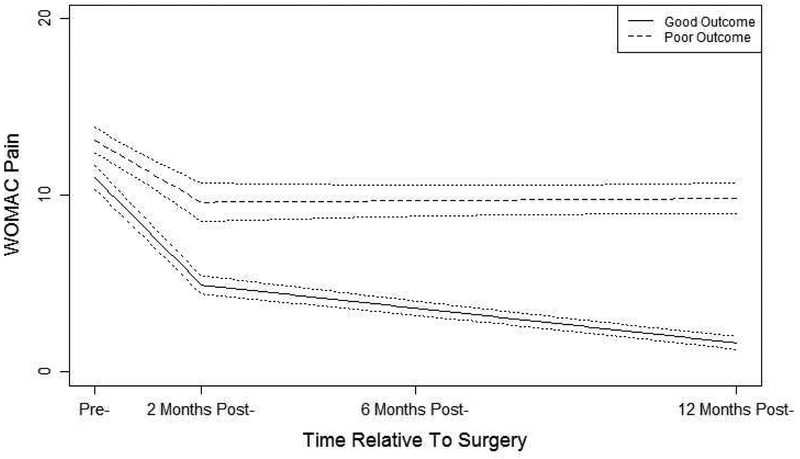

The estimated piecewise latent class trajectories and 95% CI for each trajectory type for WOMAC Pain and Function are depicted in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. For WOMAC Pain trajectories, the first trajectory class is labeled as good pain outcome class comprising 82% of the sample. On average, patients in this class have high pre-surgery pain two weeks prior, a sharp drop after the surgery, and further gradual reduction of pain toward one-year post surgery. The second trajectory class was labeled as poor pain outcome class comprising 18% of the sample. On average, patients in this class have slightly higher pain scores two weeks prior to surgery as compared to the good pain outcome class, followed by a modest improvement during the two-month post-surgery period, and no further pain relief thereafter. As consistent with the entropy of 0.89, these good and poor pain outcome trajectory classes are well separated.

Figure 1:

Estimated pain trajectory classes from the two-class piecewise latent class growth analysis and 95% CIs.

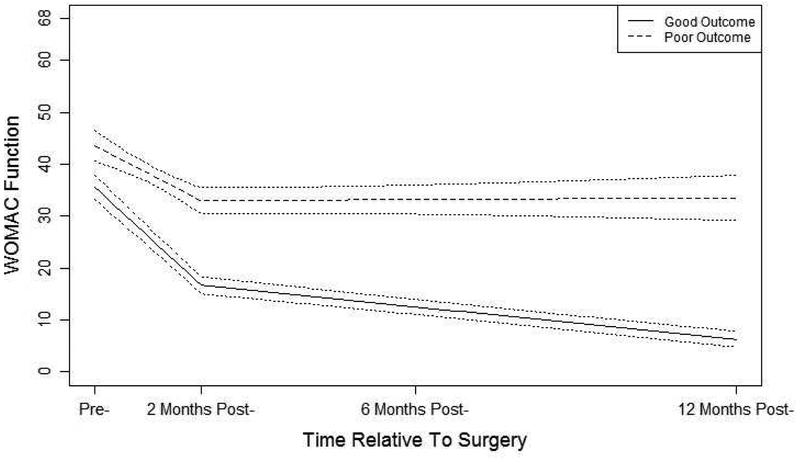

Figure 2:

Estimated function trajectory classes from the two-class piecewise latent class growth analysis and 95% CIs.

WOMAC Function trajectory classes showed similar patterns to the WOMAC Pain classes. The first function trajectory class was labeled as good functional outcome comprising 82% of the sample. High levels of pre-surgery functional deficits go down sharply after the surgery and decline continues gradually up to the 12-month period. The second trajectory class was labeled as poor functional outcome class comprising 18% of the sample. In this class, high levels of pre-operative functional deficits improve modestly after the surgery but no further improvement up to the 12-month period. As consistent with the entropy of 0.87, these two classes show clearly different patterns of functional deficits.

Agreement between Pain and Function Outcome Types

Dumenci’s latent Kappa, a chance-corrected agreement between latent pain and function trajectory types, was high (Kl = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.61 – 0.80) suggesting that patients tend to belong to either good or poor trajectory types for both pain and function (78% and 14%, respectively). However, the confidence interval around Kl excludes unity suggesting that significant number of patients (9%) have good-poor trajectory type combinations of pain and function.

Prediction of WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function Trajectories

Table 2 shows the results from the predictions of WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function trajectory classes. Accounting for all other predictors, having lower income (OR: 0.330, p=0.004), higher pain catastrophizing (OR: 1.060, p=0.007) and larger number of painful body regions (OR: 1.142, p=0.007) were associated with an increased likelihood of being in the poor outcomes class for WOMAC Pain scores. Higher baseline pain (OR: 1.220, p=0.007) and lower age (OR: 0.929, p=0.025), higher pain catastrophizing (OR: 1.047, p=0.033) and larger number of painful body regions (OR: 1.114, p=0.035) were associated with being in the poor outcomes class for WOMAC Function scores.

Table 2.

Predictors of latent pain and function outcome types (0 = good; 1 = poor)

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictora | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Outcome: WOMAC Pain | ||||||

| Income | 0.262 | 0.135 – 0.511 | <0.001 | 0.330 | 0.150 – 0.715 | 0.004 |

| Catastrophizing | 1.078 | 1.040 – 1.117 | <0.001 | 1.060 | 1.014 – 1.107 | 0.007 |

| Painful body regions | 1.164 | 1.083 – 1.251 | <0.001 | 1.142 | 1.036 – 1.260 | 0.007 |

| WOMAC function | 1.060 | 1.026 – 1.094 | <0.001 | 1.026 | 0.986 – 1.068 | 0.185 |

| Comorbidity | 1.082 | 1.013 – 1.156 | 0.017 | 0.962 | 0.863 – 1.071 | 0.469 |

| BMI | 1.014 | 0.969 – 1.062 | 0.545 | 0.988 | 0.936 – 1.043 | 0.662 |

| Gender (0=M; 1=F) | 0.817 | 0.435 – 1.533 | 0.520 | 0.633 | 0.297 – 1.347 | 0.225 |

| Depression | 1.343 | 0.676 – 2.667 | 0.391 | 1.115 | 0.440 – 2.826 | 0.814 |

| Opioid use | 1.001 | 0.993 – 1.009 | 0.789 | 0.997 | 0.983 – 1.011 | 0.610 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.989 | 0.973 – 1.005 | 0.190 | 1.011 | 0.987 – 1.036 | 0.358 |

| Outcome: WOMAC Function | ||||||

| WOMAC pain | 1.340 | 1.187 – 1.514 | <0.001 | 1.220 | 1.052 – 1.415 | 0.007 |

| Age | 0.916 | 0.874 – 0.966 | <0.001 | 0.929 | 0.870 – 0.993 | 0.025 |

| Catastrophizing | 1.083 | 1.045 – 1.123 | <0.001 | 1.047 | 1.002 – 1.094 | 0.033 |

| Painful body regions | 1.161 | 1.078 – 1.250 | <0.001 | 1.114 | 1.006 – 1.234 | 0.035 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.980 | 0.965 – 0.996 | 0.017 | 1.005 | 0.981 – 1.029 | 0.650 |

| Gender (0=M; 1=F) | 0.926 | 0.488 – 1.756 | 0.809 | 0.777 | 0.344 – 1.752 | 0.535 |

| BMI | 1.003 | 0.956 – 1.052 | 0.899 | 0.974 | 0.926 – 1.023 | 0.295 |

| Opioid use | 1.004 | 0.994 – 1.014 | 0.371 | 1.003 | 0.993 – 1.013 | 0.464 |

Predictors were measured at baseline.

DISCUSSION

Patients undergoing KA report substantially reduced levels of pain and improved self-reported function two to three months following surgery as compared to the preoperative assessment and then continued gradual improvements for both pain and function up to one year post-surgery11,30. In our study, this pattern held true for 78% of the patients (good outcome). For 14% of the sample, however, patients had some reduction of pain and a somewhat improved function up to two months after the surgery but after two months there was no change up to one-year post-surgery (i.e., poor outcome). The remaining sample of approximately 9% experienced either a good pain and poor function outcome or vice versa. Framed a different way, 82% of the sample had a good WOMAC Pain outcome while 18% had a poor WOMAC Pain outcome. For WOMAC Function, 82% had a good outcome while 18% had a poor outcome. In addition to the statistical measure of entropy, a visual inspection of the good versus poor outcome trajectories provides further evidence that some patients need additional treatment to address poor pain or function outcome.

Differences between good and poor outcome trajectories are noteworthy. For example, participants in the poor WOMAC Function outcome subgroup had an average 12-month outcome score that approximated the preoperative scores for participants in the good WOMAC Function subgroup. Similar findings were noted for WOMAC Pain. These data make a strong case for persistent substantial pain and poor function in these poor outcome subgroups. The mean WOMAC Pain score of approximately 10 at one year in the poor WOMAC Pain subgroup, for example, is equivalent to reports of moderate pain for all 5 WOMAC Pain items (walking, stairclimbing, at night, sitting, and standing) or severe pain on at least 3 of five items and mild pain on one item. A WOMAC Pain score of 10 reflects substantial pain during many routine activities. Similar activity difficulty profiles are noted for the poor WOMAC Function subgroup. These good and poor WOMAC subgroups, in our view, represent vastly different outcomes.

Because the poor outcome subgroups had persistent and substantial pain and poor function, methods for identifying these subgroups should be a high priority for clinicians treating these patients. It is possible that interventions targeting the factors associated with the poor outcome subgroups could make a substantial impact on the outcomes following surgery. Given that almost one million knee arthroplasty surgeries were done in the US in 201535, poor outcome potentially impacts up to 200,000 patients per year.

We found some independent baseline predictors of poor outcome subgroup membership. Participants in the poor WOMAC Pain outcome subgroup had a higher pain catastrophizing score, larger number of painful body regions, and lower income while participants in the poor WOMAC Function subgroup had higher pain catastrophizing scores, larger number of painful body regions, worse baseline WOMAC Pain scores, and were younger as compared to the good outcome subgroups. These data suggest that reducing pain catastrophizing among those with very high (severe) pain catastrophizing scores and reducing the number of painful body regions prior to surgery offers potential for reducing risk of poor outcome following KA. Innovative intervention strategies are needed to reduce pain catastrophizing and number of painful body regions prior to KA surgery in order to reduce the poor outcome rates though this requires formal testing in future research.

Our finding that some participants have a good pain outcome but a poor function outcome or vice versa is potentially important. Interventions designed to address these outcomes will likely need to be different to specifically address either the persistent pain or the persistent functional deficits. Because the sample size of persons with differing pain versus function outcomes is fairly small, this finding should be considered as preliminary though implications for treatment are substantial if one can predict whether the person being treated is at risk for either substantial pain or substantial functional deficit following surgical recovery. Our data also support the argument that both pain and self-reported function should be measured and that one measure does not always serve as a surrogate for the other.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to generate good and poor outcome trajectories for the commonly used WOMAC Pain and Function scales in persons following KA. We used a model-based approach without resorting to an arbitrary cut point applied to continuous pain and function scores to determine the groupings of postsurgical pain and self-reported function outcomes. Consequently, the poor outcome groups identified in previous studies may not refer to the same subgroup of patients that we identified in this study. These differing approaches to defining poor outcomes may also partially explain the discrepancy between predictors of poor outcomes reported in previous studies12,23,24 and our study.

Our study has some limitations. The KASTPain recruitment plan required our participants to have moderate to high levels of pain catastrophizing (i.e., scores of 16 or higher on the pain catastrophizing scale) prior to surgery. Therefore, our results may not generalize to KA patients with little or no pain catastrophizing. However, patients in our study had 12-month self-reported WOMAC Pain and Function outcomes that approximated those of several large sample longitudinal cohorts of patients recruited without screening criteria for pain catastrophizing36–38. Also, the magnitude of pain catastrophizing in the prediction of WOMAC Pain and WOMAC Function good and poor outcome classes was possibly underestimated due to the restriction in range problem in pain catastrophizing scores attributable to the eligibility criteria39. While our KASTPain trial indicated no effect of pain coping skills training on outcome following KA for persons with pain catastrophizing scores of ≥ 1618, the current analyses suggest that persons with extremely high levels of pain catastrophizing are at risk for poor outcome. This relatively small subgroup of patients may benefit from pain coping treatment though this requires further study. Finally, our participants were recruited from academic medical centers which may reduce generalizability to patients treated in community practices.

In conclusion, approximately 20% of patients exhibiting moderate to high levels of pain catastrophizing experience poor outcome in either pain or self-reported function up to 1 year following KA. Poor outcome subgroups demonstrated substantial persistent moderate or higher pain with routine activity or moderate or higher difficulty with daily functional activities. Some predictors of poor outcome were found and these predictors may serve as intervention targets to reduce risk of poor outcome for this substantial population of patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT SECTION:

Funding/Support: The study was supported by a grant (UM1AR062800) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Support was also provided by an NIH CTSA grant (UL1TR000058) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences to Virginia Commonwealth University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The NIH or NIAMS had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We thank the participants who enrolled in this study. We also thank the physical therapists and nurses for their role in providing the interventions under study as well as study staff at Duke University, New York University, Southern Illinois University, Virginia Commonwealth University and Wake Forest University. Study staff, physical therapists and nurses received salary support from the NIAMS/NIH grant for their participation in the study. We also wish to thank study psychologists at each site (received salary support from the NIAMS/NIH grant).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

COMPETING INTEREST STATEMENT

There are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Levent Dumenci, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, 1301 Cecil B. Moore, Ave., Ritter Annex, Room 939, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA 19122, ldumenci@temple.edu, phone: 215-204-4099, fax: 215-204-1854

Robert A. Perera, Department of Biostatistics, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond VA, USA

Francis J. Keefe, Pain Prevention and Treatment Research, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Dennis C. Ang, Department of Medicine, Section of Rheumatology, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

James Slover, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, New York University Longone Medical Center, New York, New York, USA

Mark P. Jensen, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Daniel L. Riddle, Departments of Physical Therapy, Orthopaedic Surgery and Rheumatology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA

References

- 1.Baker PN, van der Meulen JH, Lewsey J, Gregg PJ. The role of pain and function in determining patient satisfaction after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89-B(7):893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nam D, Nunley RM, Barrack RL. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a growing concern? Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(11):96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, et al. Knee replacement. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1331–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JG, Wixson RL, Tsai D, Stulberg SD, Chang RW. Functional outcome and patient satisfaction in total knee patients over the age of 75. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11(7):831–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawker G, Wright J, Coyte P, Paul J, Dittus R, Croxford R, et al. Health-related quality of life after knee replacement. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1998;80(2):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Pehrsson T, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Patient satisfaction after knee arthroplasty: A report on 27,372 knees operated on between 1981 and 1995 in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(3):262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heck DA, Robinson RL, Partridge CM, Lubitz RM, Freund DA. Patient outcomes after knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;356:93–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open. 2012;2(1):e000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott CE, Bugler KE, Clement ND, MacDonald D, Howie CR, Biant LC. Patient expectations of arthroplasty of the hip and knee. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2012;94(7):974–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bullens PH, van Loon CJ, de Waal Malefijt MC, Laan RF, Veth RP. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: a comparison between subjective and objective outcome assessments. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(6):740–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wylde V, Dennis J, Beswick AD, Bruce J, Eccleston C, Howells N, et al. Systematic review of management of chronic pain after surgery. Br J Surg. 2017;104(10):1293–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowsey MM, Smith AJ, Choong PF. Latent Class Growth Analysis predicts long term pain and function trajectories in total knee arthroplasty: a study of 689 patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(12):2141–2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diduch DR, Insall JN, Scott WN, Scuderi GR, Font-Rodriguez D. Total knee replacement in young, active patients. Long-term follow-up and functional outcome. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1997;79(4):575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bachmeier CJ, March LM, Cross MJ, Lapsley HM, Tribe KL, Courtenay BG, et al. A comparison of outcomes in osteoarthritis patients undergoing total hip and knee replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2001;9(2):137–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scuderi GR, Bourne RB, Noble PC, Benjamin JB, Lonner JH, Scott WN. The new knee society knee scoring system. In: Clin Orthop Relat Res. Vol 470 ; 2012:3–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Judge A, Arden NK, Cooper C, Kassim JM, Carr AJ, Field RE, et al. Predictors of outcomes of total knee replacement surgery. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(10):1804–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riddle DL, Keefe FJ, Ang D, J K, Dumenci L, Jensen MP, et al. A phase III randomized three-arm trial of physical therapist delivered pain coping skills training for patients with total knee arthroplasty: The KASTPain protocol. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riddle DL, Keefe FJ, Ang DC, Slover JD, Jensen MP, Bair MJ, et al. Pain coping skills training for patients who catastrophize about their pain prior to knee arthroplasty: A multisite randomized clinical trial. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and Validation. Psych Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32(4):345–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40(9):771–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McConnell S, Kolopack P, Davis AM. The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC): a review of its utility and measurement properties. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(5):453–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen LC, Sing DC, Bozic KJ. Preoperative Reduction of Opioid Use Before Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(9):282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodman SM, Parks ML, McHugh K, Fields K, Smethurst R, Figgie MP, et al. Disparities in Outcomes for African Americans and Whites Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Literature Review. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(4):765–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller A, Hartmann M, Mueller K, Eich W. Validation of the arthritis self-efficacy short-form scale in German fibromyalgia patients. Eur J Pain. 2003;7(2):163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold LM, Stanford SB, Welge JA, Crofford LJ. Development and testing of the fibromyalgia diagnostic screen for primary care. J Womens Health. 2012;21(2):231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riddle DL, Perera RA, Jiranek WA, Dumenci L. Using surgical appropriateness criteria to examine outcomes of total knee arthroplasty in a United States sample. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67(3):349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riddle DL, Ghomrawi H, Jiranek WA, Dumenci L, Perera RA, Escobar A. Appropriateness Criteria for Total Knee Arthroplasty: Additional Comments and Considerations. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2018;100(4):e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riddle DL, Perera RA, Stratford PW, Jiranek WA, Dumenci L. Progressing toward, and recovering from, knee replacement surgery: A five-year cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(12). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rupp Templin JH,Henson RA AA. Diagnostic Measurement: Theory, Method, and Application. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. 1st ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dumenci L The Psychometric Latent Agreement Model (PLAM) for Discrete Latent Variables Measured by Multiple Items. Organ Res Methods. 2011;14(1):91–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asparouhov T, Muthen BO. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: A 3-step approach ising Mplus. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 2014;21(3):329–341. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dowsey MM, Robertsson O, Sundberg M, Lohmander LS, Choong PFM, Dahl A. Variations in pain and function before and after total knee arthroplasty: a comparison between Swedish and Australian cohorts. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25(6):885–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins JE, Donnell-Fink LA, Yang HY, Usiskin IM, Lape EC, Wright J, et al. Effect of Obesity on Pain and Functional Recovery Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2017;99(21):1812–1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA, Sledge CB. Predicting the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2004;86-A(10):2179–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mendoza JL, Mumford M. Corrections for Attenuation and Range Restriction on the Predictor. J Educ Stat. 1987;12(3):282–293. [Google Scholar]