Abstract

Background

Breakfast consumption is associated with better diet quality and healthier weights, yet many adolescents miss breakfast. Nationally, 17.1% of students participate in the School Breakfast Program (SBP). Only 10% of high school students participate.

Objective

Evaluate an environmental intervention to increase SBP participation in high schools.

Design

A group randomized trial was carried out from 2012–2015.

Participants/setting

Ninth and tenth grade students enrolled in sixteen rural schools in Minnesota (median 387 students) were randomized to intervention or control condition.

Intervention

A school-based intervention that included two key components was implemented over a 12 month period. One component focused on increasing SBP participation by increasing student access to school breakfast through changes in school breakfast service practices (e.g. serving breakfast from a grab-n-go cart in the atrium; expanding breakfast service times). The other component focused on promoting school breakfast through student-directed marketing campaigns.

Main outcome measure

Change in school-level participation in the SBP was assessed between baseline (among ninth and tenth graders) and follow-up (among tenth and eleventh graders). School meal and attendance records were used to assess change in school-level participation rates in the SBP.

Statistical analyses

The Wilcoxon test was used for analysis of difference in change in mean SBP participation rate by experimental group.

Results

The median change in SBP participation rate between baseline and follow-up was 3% (IQR 13.5%) among the 8 schools in the intervention group and 0.5% (IQR 0.7%) among the 8 schools in the control group. This difference in change between groups was statistically significant (Wilcoxon test p=0.03). The intervention effect increased throughout the intervention period, with change in mean SBP participation rate by the end of the school year reaching 10.3% (95% CI 3.0, 17.6). However, among the intervention schools, the change in mean SBP participation rates was highly variable (range: −0.8 to 24.8%).

Conclusions

Interventions designed to improve access to the SBP by reducing environmental and social barriers have potential to increase participation among high school students.

Keywords: school breakfast program participation, adolescents, high school, rural

Introduction

In 1975 the School Breakfast Program (SBP) was established in the U.S. to support child nutrition and health. This federally assisted meal program operates in public and nonprofit private schools. Like the National School Lunch Program, all children attending a school that participates in the SBP may purchase a breakfast or receive breakfast free or at a reduced price if eligible. The program has the potential to improve child nutrition because research indicates that eating breakfast is positively associated with the nutritional quality of the diet1 and inversely associated with body mass index2 in children.

Participation in the SBP is low in high schools, which is concerning because breakfast skipping is common among adolescents. In high schools 32% of those eligible for free meals; 21% of those eligible for reduce price meals; and 5% of those not eligible for free or reduced price meals eat school breakfast on an average day3. These low participation rates would be of limited concern if breakfast were consumed elsewhere instead (e.g. at home). But, about 30% of adolescents in the U.S. do not eat breakfast at home, school, or elsewhere on a given day4.

A variety of strategies have been proposed to increase SBP participation5,6. The strategies include offering free breakfast to all students; providing a grab-n-go breakfast in the cafeteria and hallways; allowing students to eat school breakfast in locations outside the cafeteria such as hallways and classrooms; offering a second chance to get breakfast in the morning (e.g. serve breakfast both before school and between first and second periods); and promoting school breakfast through social marketing campaigns. These strategies are designed to address an assortment of barriers to SBP participation, such as social stigma associated with the program, time constraints, inconvenience, and not feeling hungry early in the early morning.

Limited research has been carried out to evaluate whether the aforementioned strategies are effective in increasing SBP participation, particularly in the context of high schools. Most studies carried out to date have focused on elementary7–11 or middle12–14 schools. Only three studies have evaluated strategies to increase SBP participation in high schools 15–17, and none utilized a randomized controlled trial design. Rather, one study utilized a pretest/posttest design16, one relied on a quasiexperimental design15, and the third was a pilot study in which only qualitative evaluation data was collected17. Consequently, there is a need for further research to evaluate strategies to increase SBP in high schools.

To address the need for rigorous evaluation data, we carried out a group randomized trial to evaluate a school-based intervention designed to increase SBP participation in high schools in rural areas. The intervention (Project breakFAST) was designed to increase SBP participation by 1) increasing the availability and ease of accessing SBP through school-wide policy changes (e.g., grab-n-go menu, service outside the cafeteria, second chance breakfast); 2) addressing normative and attitudinal beliefs through school-wide SBP marketing (e.g., tasty foods, for all students); and 3) providing opportunities for positive interactions that encourage eating school breakfast with social support and role modeling from peers and teachers (e.g., eating in the hallway, classroom).

The trial carried out to evaluate the Project breakFAST intervention was conducted with 16 rural high schools in Minnesota. Rural high schools were of interest because rates of overweight and obesity are higher among rural youth compared to those living in metropolitan areas18. In addition, research evaluating interventions to increase SBP participation in rural high schools is lacking. The authors hypothesized that change in school-wide SBP participation between baseline and follow-up would differ between intervention and control schools, with participation increasing to a greater extent in the intervention schools.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Recruitment, and Enrollment

A group randomized trial with a convenience sample of 16 Minnesota schools was conducted between 2012 and 2015, with the school as the experimental unit. The schools were identified through an open invitation posted on the Minnesota School Nutrition Association website19 and listserv. Informational webinars were conducted for interested school personnel, who were mainly principals and food service directors. Inclusion criteria included being located outside of the seven-county Twin Cities metropolitan area; not having a grab-n-go reimbursable school breakfast option; low (<20%) SBP participation; sufficient student enrollment (> 500); and student minority enrollment (≥10%).

Randomization was stratified by wave, with eight schools randomized in each of two waves by the study statistician. Using random permutation, within each wave four schools were allocated to implement the intervention and four to the control condition. Schools randomized to the control condition received a delayed intervention one year after collection of follow-up measures. Further details of the design and randomization process are described elsewhere3.

SBP participation among those in grades 9 and 10 in the school preceding implementation of the intervention constituted the baseline measurement period, and SBP participation among those in grades 10 and 11 during the school year the intervention was implemented constituted the follow up period.

The Institutional Review Board of University of Minnesota approved study procedures. Parental consent and student assent were not required for the de-identified school administrative data used for the analyses reported in this manuscript. The trial was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/): NCT02004977

Project breakFAST Intervention

The primary focus of the Project breakFAST intervention was to address the environmental and social factors in the high school setting that potentially moderate the students’ intention to eat a school breakfast. A detailed description of the theoretical framework and best practice recommendations that informed the design of the intervention are available elsewhere3. In short, two theories were drawn upon in developing the intervention. The Social Ecologic Model, which refers to the interplay between individual, social, and environmental factors20, was utilized in conjunction with the Theory of Planned Behavior, which refers to how individual and normative beliefs influence intentions 21. The best practice recommendations were informed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Team Nutrition Discover Breakfast Tool Kit22, the School Nutrition Association Growing School Breakfast Participation Report23, and the National Food Service Management Institute School Breakfast Best Practice Guide24. Each school principal, food service director, and the study principal investigator signed a memorandum of understanding before randomization occurred committing to three overarching intervention components: provide a grab-n-go breakfast outside of the cafeteria, allow eating in the hallway, and develop a student-led marketing campaign. Key details of the full intervention are described as follows:

School Breakfast Expansion Team

The intervention included creating a School Breakfast Expansion Team (SBET) at each school. Most teams consisted of an existing school wellness committee and/or a new committee, and included multiple stakeholders. The SBET team was designed to meet three times before implementation of changes to the SBP and twice after implementation had begun. The number of team meetings varied by school depending on members involved, time, and availability. SBET meetings were structured to focus on assessment and goal setting (first meeting); developing an action plan for increasing school breakfast access (second meeting); developing a communication plan to raise awareness of the breakfast program (third meeting); and monitoring progress and discussing ways to address challenges/barriers to implementing plans (fourth and fifth meetings

Provide grab-n-go breakfast outside of the cafeteria

Schools that did not already serve breakfast outside of the cafeteria were encouraged to provide grab-n-go breakfasts on carts outside of the cafeteria. The time of service (e.g., second chance breakfast), number and placement of carts and the menu served on the grab-n-go cart were all guided through the SBET meetings.

Allow students to eat breakfast in the hallways

As needed, change in school policy to allow students to eat breakfast in the hallways in the morning was encouraged. Allowing eating in the classroom was encouraged, but framed as optional and left up to individual teachers. Breakfast friendly “Bring your breakfast!” classroom door hangers were available.

Develop and implement a student led marketing campaign

A group of students in each intervention school worked with a marketing firm to develop and implement a school-specific marketing campaign. The groups were composed of students identified by school administration who agreed to serve in the group. The marketing firm held up to 4 meetings with each student group. The meetings focused on identifying existing perceived barriers to SBP participation; developing a marketing theme unique to the school setting and student preferences; photography and/or video filming.

Intervention activities at each school were supported by the study in multiple ways. Each school was given $5,000 that could be used for intervention related expenses such as buying equipment and supplies and hard wiring hallway internet connections. The services provided by the marketing firm to support student groups in promoting school breakfast was valued at $4,000 per school. Training and implementation support were provided by the University of Minnesota Extension. Training consisted of one in-person workshop and two webinars. An Extension team member was assigned to intervention schools to provide support for the development and implementation of the intervention. The research team, Minnesota Department of Education and Extension educators worked together to develop a model in-person workshop to train foodservice directors and a least one other school personnel from each school. The workshop was held the winter prior to the academic year when the expanded SBP would be implemented. Content of the training included USDA breakfast requirements, starting an SBET, equipment options, popular menu items, marketing strategies, and best practices for an expanded breakfast program. Following implementation, booster webinars were held in the fall and spring for those who had attended the in-person workshop.

All intervention and training materials, including the Project breakFAST Toolkit, are available on the project’s website25.

Process Measures

To assess the implementation of the intervention, process evaluation measures were collected by trained staff during four unannounced school visits which took place once in each of the following months; October, November, February and April. Visits occurred during breakfast service so a checklist could be completed to document whether the expanded breakfast service and other components of the intervention were implemented. The checklist assessed where and how students get the school breakfast program (e.g. time, location and service type), the availability of vending and other food purchasing options, and whether busses arrived late that day. Assessors also documented the locations that they saw students eating breakfast, door hangers designating breakfast friendly classrooms, or school breakfast promotional materials in hallways. All intervention schools also had one unannounced visit to record school breakfast menu offerings for one week to evaluate adherence to select USDA meal pattern standards. Each intervention school completed a 13-item communication checklist twice during the intervention year (December, April) to document all communication and promotional activities used (yes/no).

Outcome Measures

The primary study outcome was change in school-level participation in the SBP between the baseline and follow-up school years for students who were in grades 9 and 10 at baseline and grades 10 and 11 at follow up. The data used to calculate SBP participation at each school at each time point, daily SBP participation and days in attendance for each child in grades 9 and 10 at baseline and grades 10 and 11 at follow up, were obtained through the company the school used for data management. Additional data of importance to the study (race, grade level, and free and reduce price meal eligibility status) were also obtained via the school’s data management software company.

The processes used by the schools to track student attendance and student participation in the school breakfast program were similar across schools. With respect to attendance, each school tracked daily student attendance using a process that involved use of classroom absence reports from teachers and absences reported by others (e.g. absences reported to the school office by parents). Students’ daily breakfast participation was tracked through the school meal software used by the school. School meal software is designed to facilitate the tracking and payment (or federal reimbursement) of school meals, with students required to enter or provide their unique identification number prior to obtaining a meal.

For schools in wave 1 baseline data were obtained for the 2012–2013 school year, follow-up measures were obtained for the 2013–2014 school year, and the Project breakFAST intervention was delivered to the intervention schools during the 2013–2014 school year. For schools in wave 2 baseline data were obtained for the 2013–2014 school year, follow-up data were obtained for the 2014–2015 school year, and the Project breakFAST intervention was delivered to intervention schools during the 2014–2015 school year. All data was transferred from each school’s data management company to the University electronically through a password protected University managed platform.

Statistical Analyses

To protect privacy, the data provided by each of the schools were de-identified. As a result, within-student changes across school years could not be examined. Hence, the data for analyses consists of school-level summary statistics for baseline and follow-up calculated from the data provided by schools for individual students in each year. These summary statistics were treated as repeated measures with schools as the unit of analysis.

The primary outcome was change in mean SBP participation rate between baseline and follow-up school years for each school, defined as follows. Percent SBP participation for an individual student in one school year was the proportion of school days on which the student received a fully-reimbursable school breakfast. The number of school days was the number of days the school recorded the child as in attendance. The school-level mean SBP participation rate was the average of the individual students’ SBP participation rate. Students enrolled for less than 30 days of the school year were excluded from this calculation.

Overall change in school-level mean SBP participation rate was calculated as the difference between the mean SBP participation rate during the follow-up school year and the baseline school year within each school. A secondary outcome of interest was the change in mean SBP participation rate at baseline and follow-up by month. For this analysis mean SBP participation rate was calculated in a manner similar to that done for mean SBP participation rate for the baseline and follow-up school years but with the calculations carried out by month from September-May.

Continuous data was summarized as median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean and standard deviation. Categorical data was summarized as counts and percentages. School level baseline characteristics of number enrolled, grade level, race, eligibility for free or reduced price meals, and chronic absenteeism were compared between groups to demonstrate the balance of the treatment groups on these possible confounders. Chronic absenteeism was defined as a student being absent more than 10% of all days enrolled. Because the sample size consisted of 8 schools in each group, the Wilcoxon test was used to compare baseline characteristics between the intervention and control groups. The primary analysis is the unadjusted analysis of the primary endpoint (change in mean SBP participation rate) using the Wilcoxon test because of the small sample size and the skewness of the data. The secondary analysis is the longitudinal analysis of change in mean SBP participation rate by month using least squares means from a linear mixed model with fixed effects for month, treatment group, and their interaction and a random intercept for school to account for within-school correlation over time.

Results

Characteristics of participating schools are presented in Table 1. The median percent of 9th and 10th grade students eligible for free or reduced price meals across the schools was 32.2% and the median percent that were non-Hispanic white was 87.8%. Median participation in the SBP during the baseline school year was 13.1%. No significant differences were found between experimental groups in the characteristics examined. Baseline-to-follow up changes in the composition of students in intervention versus control schools were also examined, and no significant differences were found.

Table 1.

Median (IQR) school-level characteristics of the schools in the Project breakFAST study combined (n=16) and by treatment group at baseline

| Combined (n=16) | Intervention (n=8) | Control (n=8) | P value c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total 9th and 10th grade student enrollment, number | 387.5 (489) | 528.5 (459.5) | 314.5 (338) | 0.34 |

| 10th grade, % | 48.2 (3) | 49.1 (3.7) | 47.7 (1.6) | 0.34 |

| Female, % | 47.8 (4.2) | 48.9 (3.5) | 47.1 (3) | 0.25 |

| Eligible for free or reduced priced school meals, % | 32.2 (15.3) | 32.2 (14.1) | 33 (15.3) | 0.83 |

| Non-Hispanic White, % | 87.8 (14.1) | 83.5 (13.6) | 90.2 (19) | 0.46 |

| Participation in School Breakfast Program a, % | 13.1 (8.1) | 13.1 (7.6) | 13.1 (8.1) | 1.00 |

| Chronic absenteeism b, % | 8 (14.5) | 7.3 (20.9) | 8 (10) | 0.96 |

School Breakfast Program participation is defined as the average annual percent of school attendance days in which a student purchased/received a reimbursable School Breakfast Program meal.

Chronic absenteeism is defined as 10% or greater missed days in a school year.

P value is from the Wilcoxon test comparing medians between intervention and control.

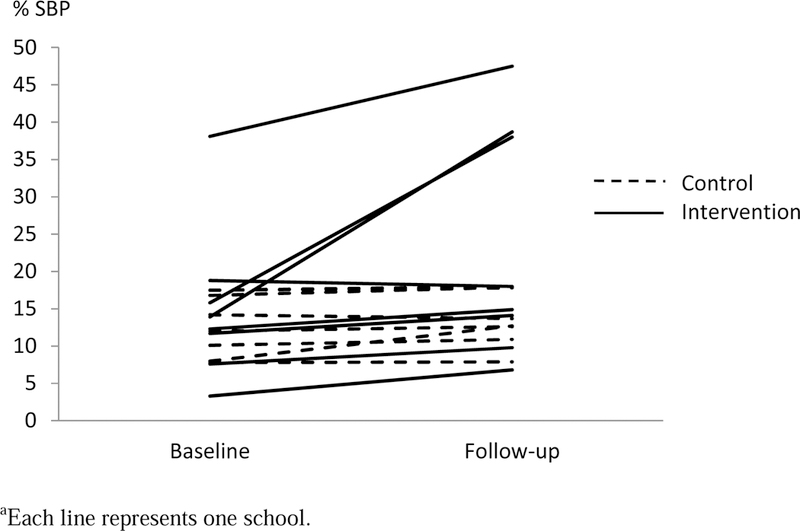

Change in School Breakfast Program Participation

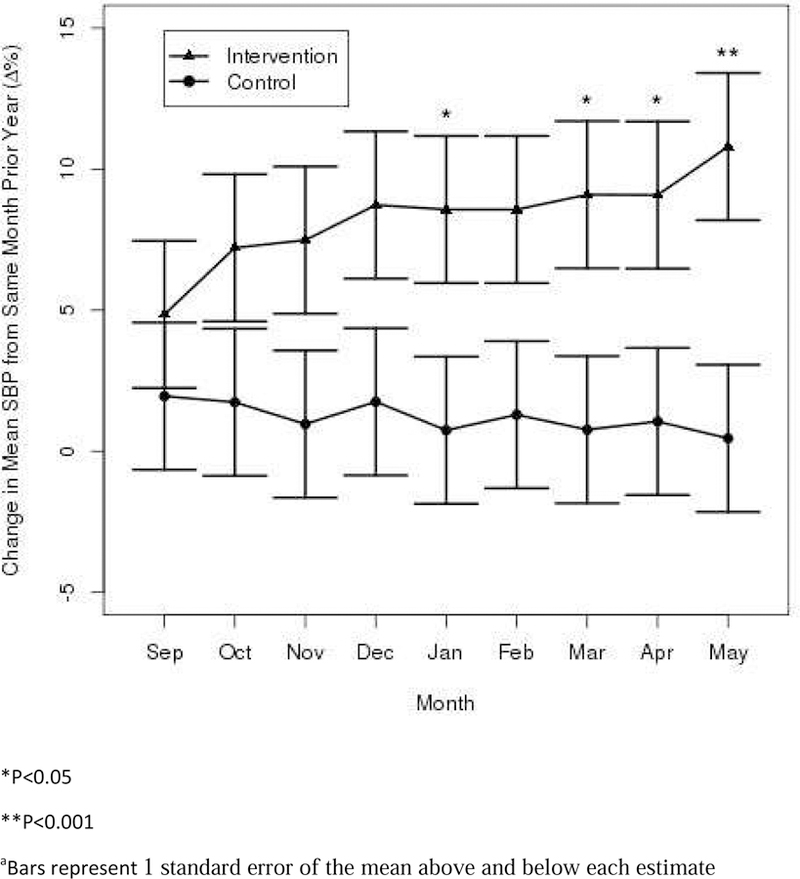

The median change in SBP participation rate between the baseline and follow-up school years was 3% (IQR 13.5%) in the intervention group and 0.5% (IQR 0.7%) among the control group, a statistically significant difference by the Wilcoxon test (p=0.03) (Table 2). Between group differences were also observed when comparing the mean change in school-level SBP participation rate (mean change 8.3 and 0.9% in the intervention and control groups, respectively). In Figure 1 the mean SBP participation rate in the baseline and follow-up school years are presented for each of the schools in the trial. Among the intervention schools the change in mean SBP participation ranged from −0.8 to 24.8%. Among the control schools the change in mean SBP participation ranged from −0.5 to 4.7%. Figure 2 shows estimates of change in school breakfast participation (SBP participation percent during follow up month minus SBP participation percent during baseline month) by month and experimental group, showing 1 standard error of the mean above and below each estimate. In the linear mixed model of the effect of intervention, month, and their interactions, the interaction was significant (F=3.52, df=8,112, p=0.001) indicating a varying-effect of the intervention by month. The general trend was towards an increasing difference favoring the intervention group as time increased. However, results achieve statistical significance only in January, March, April, and May (difference in lsmeans and 95% CIs by month: 7.8% (0.5,15.1), 8.3% (1.0,15.6), 8% (0.7,15.3), 10.3% (3.0,17.6), respectively).

Table 2.

Change in median and mean percent School Breakfast Program (% SBP) participation among students who were in grades 9 and 10 at baseline and grades 10 and 11 at follow up in schools participating in the Project breakFAST study by treatment group

| Group | n | Median | Interquartile Range | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 8 | 3 | 13.5 | 8.3 | 9.8 |

| Control | 8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.6 |

P-value for the exact Wilcoxon test p=0.03

Figure 1.

Mean Percent School Breakfast Program (%SBP) participation by students in grades 9 and 10 at baseline and grades 10 and 11 at follow-up by school for schools participating in the Project breakFAST studya

Figure 2.

Change between baseline and follow up in mean % School Breakfast Program (SBP) participationa by students in grades 9 and 10 at baseline and grades 10 and 11 at follow up by month for each experimental group for schools participating in the Project breakFAST study

Implementation of the Intervention

Process evaluation measures indicated that all of the intervention schools implemented a grab-n- go menu served outside of the cafeteria setting. In addition, all schools implemented a second chance breakfast. Schools went through a process of trial and error to determine the best expanded breakfast setup. Schools reported trying multiple hallway locations, hot versus cold foods, prepackaged meal in a bag versus choice. Breakfast menus at the intervention schools met USDA requirements for meal pattern servings of food groups. The intervention schools implemented at least one marketing and communication strategy. Communication strategies used included faculty/staff meetings (n=7), school website (n=6), school newsletter (n=6), announcements (n=6), Twitter/Tweets (n=5), outside media (n=3), and student orientation (n=3). Common promotional strategies included breakfast week kick-off (n=7), student-developed video (n=7), taste testing (n=6) and assemblies (n=5).

Discussion

Findings contribute to a limited body of research evaluating interventions to increase SBP participation in high schools15–17, and only one study evaluated environmental interventions similar to those in the Project breakFAST intervention16. Using a pre-post design, Olsta et al. examined the effect of a SBP intervention in the Midwest with a large (n=2560) and diverse (43% non-white; 27.5% eligible for free school meals) suburban high school student population16. The findings showed that the percent of students participating in the SBP on a typical day averaged about 3% at baseline and 14% at the end of the school year, an increase of 11%. This magnitude of change is similar to that found at the end of the school year in which the Project breakFAST intervention was implemented (10.3% change in mean SBP participation rate in May). Similar to results for the Project breakFAST intervention, in the Olsta study SBP participation appeared to increase over the school year 16.

The present study focused on rural schools because no previous studies have evaluated strategies to increase SBP participation in rural schools, while the need for improved nutrition in rural youth is high. As mentioned earlier, rates of overweight and obesity are higher among rural youth compared to those living in metropolitan areas18. In addition, the school food environment in small town and rural school environments are lagging behind urban and suburban schools 26. The few studies carried out to date in rural schools have focused on younger students27–30 the school lunch program30, or competitive food options 31.

Wide variation in changes in SBP participation was observed across Project breakFAST intervention schools (change ranged from −0.8 to 24.8%). The reason for the variation is unclear as there were no discernable patterns in differences in participation in intervention activities or implementation of intervention components when comparing the intervention schools with a greater increase in SBP participation with those with a lower or no change. Intervention staff informally noticed a pattern of higher levels of enthusiasm and commitment to the intervention in schools with a greater increase in SBP participation compared to those with a lower or no change. Since our process evaluation measures were not designed to measure these phenomenon, these observations are speculative.

The study has a number of strengths. Notable strengths include use of a group randomized trial design. Inclusion of a control group reduces the likelihood that study findings may be attributed to temporal trends in SBP participation. The use of objective school-provided data to measure SBP participation is another study strength. School administrative data has several major advantages over self-report SBP participation data including better representativeness of the data since non-response bias is avoided and is not dependent on students’ willingness to participate and complete specific measures. Also, measurement errors due to memory failure and response bias are circumvented when relying on school-provided data.

Study shortcomings include potentially limited generalizability of findings because the study was carried out in one geographical region and only engaged rural schools that had low SBP participation and did not offer grab-n-go breakfast at baseline. Also, the study sample was predominately white (87.8%) and higher income (67.8%). Another weakness is limited ability to explore potential explanations for variable effects of the intervention across schools due to the limited number of intervention schools and limited data collected as part of process evaluation. The study examined effects during the same school year the Project breakFAST intervention was implemented. It is possible that longer term effects are different. For example, further increases in SBP participation may occur in subsequent years due to further changes in cultural norms and habit formation. However, it is also possible that gains in SBP participation are lost over a longer period of time due to degradation of the intervention, loss of novelty, etc. For these school-level analyses the extent that students were eating breakfast at home or more than one breakfast (school and home) is unknown. This is a notable limitation as we don’t know the extent to which the observed increase in SBP participation occurred among those who could most benefit from eating breakfast at school (those who do not eat breakfast at home or school).

Conclusions

In conclusion, SBP participation in high schools can be increased by expanding access to school breakfast and addressing social norms and student beliefs through a school-wide marketing campaign. These strategies address known barriers among high school student populations, but each school is unique. Gradual increases in participation may be expected throughout the first year the intervention is implemented. In future research, the evaluation period should be extended beyond one school year so that longer-term effects can be assessed. Findings may be used to inform policy and practice implementation in the school food environment; provide a model SBP best practices implementation plan that is especially relevant for high schools; and use of Extension facilitators offers a model for wide-scale dissemination.

Research Snapshot.

Research Question

Can a school-based environmental intervention that aims to expand student access to and promote the School Breakfast Program (SBP) increase SBP participation in high schools?

Key Findings

Results from this group randomized trial indicate that SBP participation can be increased by a school-based intervention that focuses on expanding access, changing norms and beliefs about school breakfast, and student-driven promotions. The median change in the SBP participation rate between baseline and follow-up was 3% among eight schools in the intervention group and 0.5% among eight schools in the control group, a statistically significant difference in change between groups (Wilcoxon test p=0.03).

Acknowledgments

Funding/financial disclosure: NIH NHLBI R01HL113235

Clinical trial registry: Clinicaltrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/): NCT02004977

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest disclose: The authors (Marilyn Nanney, Robert Leduc, Mary Hearst, Amy Shanafelt, Qi Wang, Mary Schroeder, Katherine Grannon, Martha Kubik, Caitlin Caspi, and Lisa Harnack) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Marilyn S. Nanney, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, 717 Delaware St SE, Ste 166, Minneapolis, MN 55414, msnanney@umn.edu, 612-626-6794.

Robert Leduc, Division of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, 2221 University Avenue SE, Suite 200, Minneapolis MN 55414, robertl@ccbr.umn.edu, 651-690-6157.

Mary Hearst, Public Health Program, Saint Catherine University, 2004 Randolph Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55105, St. Paul, MN, USA, mohearst@stkate.edu, 651-690-6157.

Amy Shanafelt, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 717 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, shanafel@umn.edu, 612-626-9496.

Qi Wang, Clinical and Translational Science Institute, 717 Delaware Street SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414, wangx890@umn.edu, 612-626-5197.

Mary Schroeder, University of Minnesota Extension, 1424 E College Dr Ste 100, Marshall, MN 56258-2087, hedin007@umn.edu, 507-337-2817.

Katherine Y. Grannon, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, 420 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, 612-625-7179.

Martha Y. Kubik, College of Public Health, Department of Nursing, Temple University, 1101 W. Montgomery Ave. 3rd Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19122, youn1286@umn.edu, 215-707-8327, At time of research:, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota, 6-119A WDH, 308 Harvard St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455.

Caitlin Caspi, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota, 420 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, cecaspi@umn.edu, (612) 626-7074.

Lisa J. Harnack, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, 1300 South 2nd St, Suite 300, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55454.

References

- 1.Rampersaud GC, Pereira MA, Girard BL, Adams J, Metzl JD. Breakfast habits, nutritional status, body weight, and academic performance in children and adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc May 2005;105(5):743–760; quiz 761–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondin SA, Anzman-Frasca S, Djang HC, Economos CD. Breakfast consumption and adiposity among children and adolescents: an updated review of the literature. Pediatr Obes February 4 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.USDA Food and Nutrition Service. School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study-IV Summary of Findings November 2012. USDA Food and Nutrition Service website: https://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/expanding-your-school-breakfast-program accessed August 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.United States Department of Agriculture Food Surveys Research Group. Breakfast in America, 2001–2002 United States Department of Agriculture Food Surveys Group website; https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/DBrief/1_Breakfast_2001_2002.pdf Accessed March 6, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Share our Strength. Increasing School Breakfast Participation 2014; Share our Strength website; https://bestpractices.nokidhungry.org/school-breakfast/increasing-school-breakfast-participation. Accessed August 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Education Assocation Health Information Network. Start School with Breakfast: A Guide to Increasing School Breakfast Participation National Education Assocation Health Information Network website; http://neahealthyfutures.org/wpcproduct/start-school-with-breakfast-a-guide-to-increasing-school-breakfast-participation/. Accessed August 11, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anzman-Frasca S, Djang HC, Halmo MM, Dolan PR, Economos CD. Estimating impacts of a breakfast in the classroom program on school outcomes. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169(1):71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Wye G, Seoh H, Adjoian T, Dowell D. Evaluation of the New York City breakfast in the classroom program. Am J Public Health 2013;103(10):e59–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore GF, Murphy S, Chaplin K, Lyons RA, Atkinson M, Moore L. Impacts of the Primary School Free Breakfast Initiative on socio-economic inequalities in breakfast consumption among 9–11-year-old schoolchildren in Wales. Public Health Nutr 2014;17(6):1280–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchie LD, Rosen NJ, Fenton K, Au LE, Goldstein LH, Shimada T. School Breakfast Policy Is Associated with Dietary Intake of Fourth- and Fifth-Grade Students. J Am Diet Assoc 2016;116(3):449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddan J, Wahlstrom K, Reicks M. Children’s perceived benefits and barriers in relation to eating breakfast in schools with or without Universal School Breakfast. J Nutr Educ Behav 2002;34(1):47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoelscher DM, Moag-Stahlberg A, Ellis K, Vandewater EA, Malkani R. Evaluation of a student participatory, low-intensity program to improve school wellness environment and students’ eating and activity behaviors. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanney MS, Olaleye TM, Wang Q, Motyka E, Klund-Schubert J. A pilot study to expand the school breakfast program in one middle school. Transl Behav Med 2011;1(3):436–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris CT, Courtney A, Bryant CA, McDermott RJ. Grab N’ Go breakfast at school: observations from a pilot program. J Nutr Educ Behav 2010;42(3):208–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leatherdale ST, Stefanczyk JM, Kirkpatrick SI. School Breakfast-Club Program Changes and Youth Eating Breakfast During the School Week in the COMPASS Study. The Journal of school health 2016;86(8):568–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olsta J Bringing breakfast to our students: a program to increase school breakfast participation. The Journal of school nursing : the official publication of the National Association of School Nurses August 2013;29(4):263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haesly B, Nanney MS, Coulter S, Fong S, Pratt RJ. Impact on staff of improving access to the school breakfast program: a qualitative study. J School Health 2014;84(4):267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutfiyya MN, Lipsky MS, Wisdom-Behounek J, Inpanbutr-Martinkus M. Is rural residency a risk factor for overweight and obesity for U.S. children? Obesity 2007;15(9):2348–2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minnesota School Nutriiton Association 2018; https://www.mnsna.org/. Accessed 11/08/2018.

- 20.Townsend N, Foster C. Developing and applying a socio-ecological model to the promotion of healthy eating in the school. Public Health Nutr 2013;16(6):1101–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajzen I The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Expanding Your School Breakfast Program 2013; https://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/expanding-your-school-breakfast-program. Accessed 12/22/16.

- 23.School Nutrition Association. Growing School Breakfast Program Participation: New ways to deliver breakfast to students on the-the-go: School Nutrition Association;2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rainville A, Carr D. Best Practice Guide for In-Classroom Breakfast: The University of Mississippi National Food Service Management Institute;2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Project breakFAST: Fueling Academics and Strengthening Teens 2018; https://www.healthdisparities.umn.edu/research-studies/project-breakfast. Accessed 11/8/2018.

- 26.Nanney MS, Davey CS, Kubik MY. Rural disparities in the distribution of policies that support healthy eating in US secondary schools. J Acad NutrDiet 2013;113(8):1062–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schetzina KE, Dalton WT 3rd, Lowe EF, et al. Developing a coordinated school health approach to child obesity prevention in rural Appalachia: results of focus groups with teachers, parents, and students. Rural Remote Health 2009;9(4):1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schetzina KE, Dalton WT 3rd, Lowe EF, et al. A coordinated school health approach to obesity prevention among Appalachian youth: the Winning with Wellness Pilot Project. Fam Community Health 2009;32(3):271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graves A, Haughton B, Jahns L, Fitzhugh E, Jones SJ. Biscuits, sausage, gravy, milk, and orange juice: school breakfast environment in 4 rural Appalachian schools. J School Health 2008;78(4):197–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Addison CC, Jenkins BW, White MS, Young L. Examination of the food and nutrient content of school lunch menus of two school districts in Mississippi. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2006;3(3):278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nollen NL, Befort C, Davis AM, et al. Competitive foods in schools: availability and purchasing in predominately rural small and large high schools. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109(5):857–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]