Abstract

The repair of a fractured bone is critical to the well-being of humans. Failure of the repair process to proceed normally can lead to complicated fractures, exemplified by either a delay in union or a complete nonunion. Both of these conditions lead to pain, the possibility of additional surgery, and impairment life quality. Additionally, work productivity decreases, income is reduced, and treatment costs increase, resulting in financial hardship. Thus, developing effective treatments for these difficult fractures, or even accelerating the normal physiological repair process is warranted. Accumulating evidence shows that microRNAs (miRNAs), small non-coding RNAs, can serve as key regulatory molecules of fracture repair. In this review, a brief description of the fracture repair process and miRNA biogenesis is presented, as well as a summary of our current knowledge of the involvement of miRNAs in physiological fracture repair, osteoporotic fractures and bone defect healing. Further, miRNA polymorphisms associated with fractures, miRNA presence in exosomes, and miRNAs as potential therapeutic orthobiologics are also discussed. This is a timely review as several miRNA-based therapeutics have recently entered clinical trials for non-skeletal applications and thus it is incumbent upon bone researchers to explore whether miRNAs can become the next class of orthobiologics for the treatment of skeletal fractures.

Keywords: Fracture repair, Osteoporosis, microRNA, nonunion, exosome, bone defect, orthobiologic, miRNA

Introduction

The fracture repair process is biologically complex and characterized by various interdependent phases: hematoma formation; inflammation; intramembranous ossification; chondrogenesis; endochondral ossification and remodeling (1). Collectively, these events involve multitudes of secreted signaling messengers that activate signaling pathways resulting in the differential expression of a plethora of genes that ultimately induce progenitor cells to proliferate and differentiate leading to the repair of the fractured bone (2). These multifaceted molecular and cellular events are all well organized, both in space and time, and result in the restoration of the bone’s normal homeostatic biological and functional properties (Figure 1).

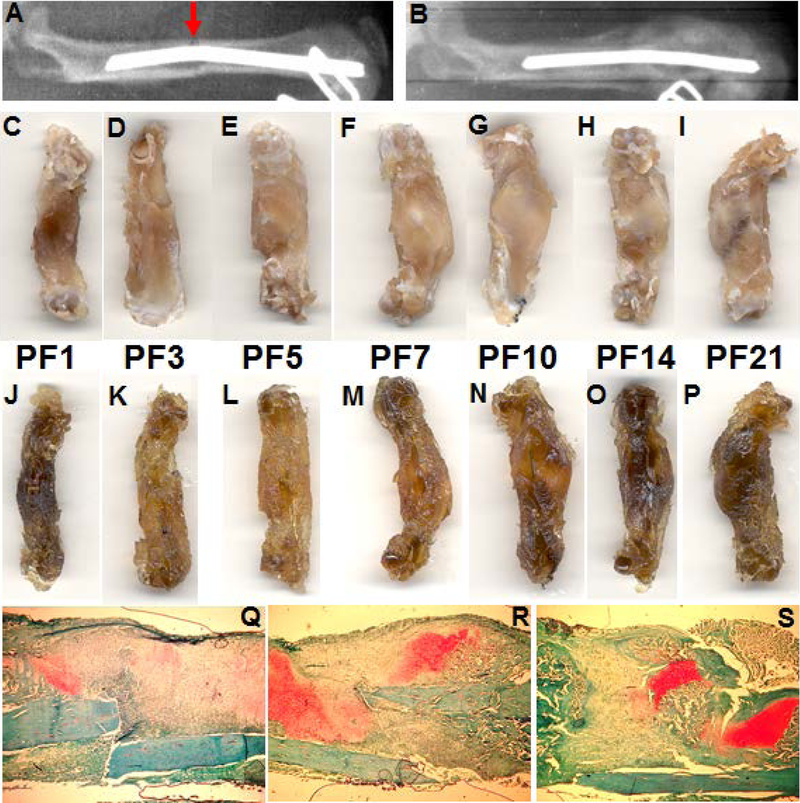

Figure 1.

Fracture repair process. A, X-ray image of a fractured (indicated by red arrow) rat femur (image take immediately after fracture); B, the same femur at post-fracture day (PFD) 21 shows the presence of the fracture callus; C-I, fractured rat femurs at PFD 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, respectively. J-P, same as C-I, following decalcification. Q-S, sections of PF day 7, 14, 21 callus, respectively, stained with safranin-o fast green. Images C and J, clearly show the hematoma that develops after the fracture (PFD1). Images F-I and M-P show the presence of the cartilaginous callus (PFD 7–21) which are also indicated as the red areas in Q, R and S (PFD 7, 14 and 21). Images N-O also show the reestablishment of the vasculature, especially O and P.

Following a fracture, a hematoma develops that represents a critical source of signaling molecules; hormones, growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines, and well as cells (inflammatory phase) (1). These molecules bind to their respective receptors on osteoprogenitor cells found in the periosteum (3), stem cells in the bone marrow (stromal and hematopoietic), and in adjacent skeletal muscle (4). Following induction of signaling pathways, these cells undergo proliferation and differentiation, ultimately leading to the formation of active osteoblasts and chondrocytes, the two cell types primarily responsible for tissue regeneration (reparative phase). Osteoblasts are predominantly involved in the formation of new (woven) bone during intramembranous ossification leading to the hard callus found adjacent to the fracture site and under the periosteum. In contrast, chondrocytes are responsible for the production of the cartilaginous soft callus found at the middle of the fracture site that stabilizes the two ends of the bone (1).

Concomitantly, the hypoxic environment created by the disruption of the vasculature induces activation of a critical physiological mechanism through hypoxia related molecular pathways (5–7), which in turn are responsible for stimulating the production of angiogenesis-related proteins leading to the neovasculature (Figure 1). Recent evidence also shows that angiogenesis is coupled to osteogenesis (8) and the formation of new blood vessels is primarily responsible for delivering oxygen and nutrients needed for the formation of new tissue, as well as the transport of blood cells (both inflammatory as well as circulating stem cells). Further, the neovasculature may also provide vital signals that regulate the process of bone fracture repair (9).

As the repair process proceeds, the cartilaginous soft callus begins to undergo endochondral ossification, that is, calcification, and ultimately results in the replacement of cartilage with bone (10). Although, it was previously accepted that chondrocytes undergo apoptosis followed by the migration of osteoblasts as the cells responsible for the replacement of cartilage with bone, more recently, it was demonstrated that a significant percentage of these chondrocytes, not only survive but proliferate and actually transdifferentiate into osteoblasts (11,12). Ultimately, this cartilage to bone conversion is coordinated by the invading vasculature and the stimulation of pluripotency genes (13).

Finally, the fracture repair process is completed by the remodeling of the irregular woven bone to lamellar and eventually cortical bone via secondary bone formation (remodeling phase). This process is driven by the coupled activities of osteoclasts that are responsible for bone resorption followed by the production of osteoid by osteoblasts. Eventually, the osteoid matrix will calcify thereby returning the bone structure to its original architecture and function (14).

Clinically, approximately 15–16 million bone fractures occur in the United States annually (15). Even though the majority of them heal normally, approximately 10–15% are characterized by either delayed healing or nonunion. These complicated fractures increase patient morbidity and mortality. For example, the 5-year morality rate for osteoporotic hip fractures ranges from 38–64%, depending on age, with a similar range of 29–50% reported for vertebral fractures (16). These fractures also cause patients to experience prolonged pain, carry the possibility of additional surgical procedures, and impair quality of life. Additionally, patient work productivity often decreases, leading to reduced income, while at the same time they face the financial burden of increased treatment costs (17–18). Generally, the four major factors associated with delayed fracture repair or nonunions are: 1) anatomic factors (e.g., location and type of fracture and degree of bone loss, extent of surrounding soft tissue damage/quality); 2) treatment-related factors (e.g., infection, inadequate reduction, poor stabilization/fixation); 3) patient-related factors (e.g., sex, age, and comorbidities such as diabetes, osteoporosis, hormonal deficiencies, etc.); and 4) drug factors (e.g., illicit drug abuse, smoking, alcohol consumption, prescription medications) (19).

Although several physical (e.g. low intensity pulsed ultrasound) and biological therapies (e.g. bone grafts, BMPs, PTH) are being clinically used (20), unfortunately, only surgery remains the definitive treatment for these difficult fractures. As such, we need to develop additional therapeutic strategies that not only treat difficult fractures, but will also accelerate normal physiological fracture repair. One such approach may be the use of miRNAs. Herein we review our current knowledge regarding general aspects of miRNA biology, followed by their involvement during physiological fracture repair. In addition, we will review what is known about their expression in osteoporotic fractures and bone defect regeneration. We will then discuss miRNA polymorphisms and fractures, miRNAs in exosomes, and finally miRNAs as potential therapeutic orthobiologics.

miRNAs biogenesis

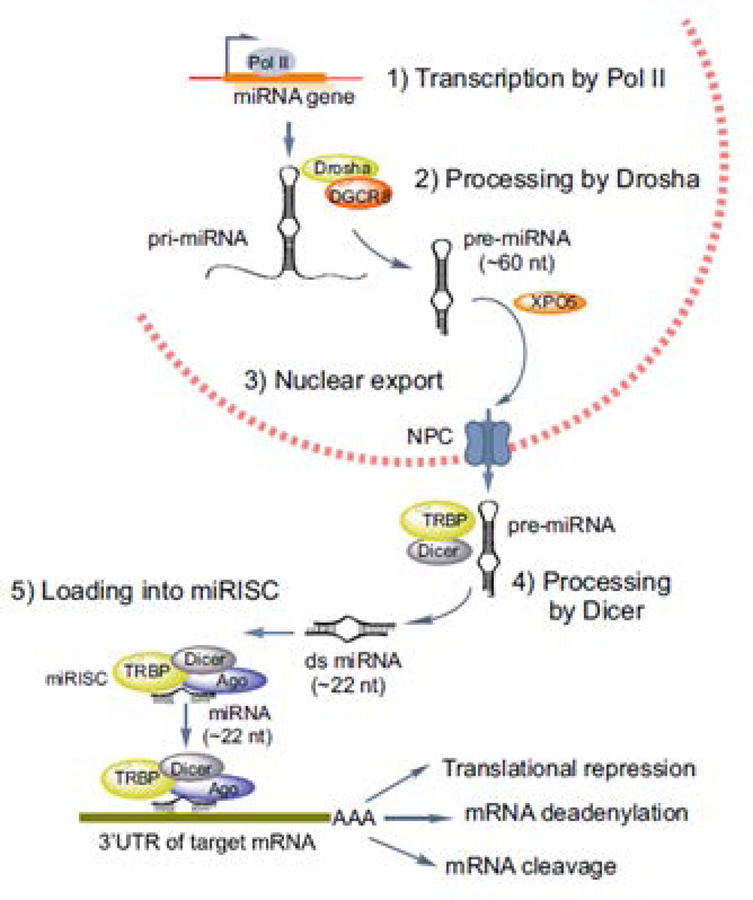

A wide variety of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) have been characterized in recent years. These include short interfering RNAs (siRNAs), piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), and, of course, miRNAs. (21). While we are only beginning to understand how some of these types of noncoding RNAs function in various tissues, there is now a large body of evidence regarding the role of miRNAs in fracture repair. As such, they are the focus of this review. miRNAs are a class of small (20–24nt) noncoding RNAs that function as post-transcriptional gene expression regulators (22). miRNAs are initially transcribed by RNA polymerase II as hairpin primary microRNAs (pri-microRNAs) and are subsequently processed by the RNase III enzyme, Drosha and DGCR8 (DiGeorge Critical Region 8) in the nucleus (Figure 2). Once exported to the cytoplasm, they further undergo processing by another enzyme, Dicer and TRBP (transactivation response element RNA-binding protein), to generate the small 22 nucleotide long double stranded mature miRNA. During this processing, the unwinding of the duplex occurs and generates the single strand miRNA. This single strand mature miRNA is incorporated into a larger molecular complex known as the RNA-induced silencing complex or RISC, which also includes Dicer, TRBP and other associated proteins, including Argonaute (Ago), which are critical to RISC function. Finally, the RISC complex binds to the target mRNA through pairing of the miRNA to the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNA and either induces deadenylation, degradation of the mRNA, or blocks it from being translated (23). Regardless of the mode, this process results in gene silencing via inhibition of protein production (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MicroRNA biogenesis. The steps resulting in the functional production of functional miRNAs are schematically represented in this figure. Adopted from Lekka and Hall, (26) with permission.

This process is ubiquitous, and it is estimated that over 60% of mammalian genes are post-transcriptionally regulated by miRNAs (24). Many studies have shown that when one or more members of a very broadly conserved miRNA family are deleted in mice, the animals show a diverse array of abnormal phenotypes in many tissues and in some cases results in lethality (25). Other studies demonstrated associations between aberrant miRNA expression and human diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular and neurological disorders (26). Additionally, miRNAs have also been associated with repair of many tissues, including, liver, kidney, heart, skin, lung, and nervous system (27). More importantly, and as it relates to the skeletal system, studies have found that miRNAs are key components of osteogenesis and bone homeostasis via their regulation of skeletal cell function, and may be linked to diseases such as osteoporosis, osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), and osteosarcoma (28). Lastly, miRNAs have been associated with fracture repair and bone regeneration in general, as will be described in detail in the following sections.

miRNA profiling and fractures

Clinical osteoporosis studies

Several studies have taken a profiling approach in describing differentially expressed miRNAs during fracture repair and most of these studies have focused on osteoporotic fractures. For example, a clinical study isolated miRNAs from the serum of 20 patients with hip fractures and identified 83 distinct miRNAs (29). A separate validation analysis found differentially regulated miRNA from the serum (30 osteoporotic and 30 nonosteoporotic) and bone (20 osteoporotic and 20 nonosteoporotic) patients. Of the differentially regulated miRNAs, 9 (miR-21, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-93, miR-100, miR-122a, miR-124a, miR-125b, and miR-148a) were significantly upregulated in the serum of patients with osteoporosis, while in bone from osteoporotic patients, miR-21, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-25, miR-100, and miR-125b displayed significant higher expression. Lastly, five miRNAs (miR-21, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-100, and miR-125b) were upregulated in both serum and bone from osteoporotic patients. Given these results, the authors suggest that miRNAs may be used as diagnostic biomarkers for osteoporosis, as well as targets for treating bone loss in these patients (29). Another study investigated whether circulating (serum) miRNAs exhibit changes in patients with recent osteoporotic hip fractures and showed that miR-10a-5p, miR-10b-5p, miR-22–3p were upregulated whereas miR-133b, miR-328–3p, and let-7g-5p were downregulated in serum levels in response to the fracture. The study also confirmed the significant downregulation of miR-22–3p, miR-328–3p, and let-7g-5p in a cohort of 23 patients (11 control, 12 fracture). Lastly, the study showed that five individual miRNAs (miR-100–5p, let-7g-5p, miR-21–5p, miR-24–3p and miR-148a-3p) were able to induce osteogenic differentiation of human adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro (30). A more comprehensive study examined the expression of 760 miRNAs in trabecular bone samples obtained from the femoral heads of patients with osteoporotic hip fractures and showed that 13 miRNAs (let-7i, miR-135a, miR-137, miR-181a-2, miR-187, miR-193a-3p, miR-214, miR-330–5p, miR-518f, miR-519d, miR-524, miR-636, miR-643) displayed significant differences: seven with higher levels in bones from osteoporotic patients and the other six in the non-fractured bones. The authors selected six miRNAs (miR-187, miR-193a-3p, miR-214, miR518f, miR-636, and miR-210) for further analysis and found that miR-187 levels were 5.3-fold higher in the non-fracture group whereas miR-518f levels were 8.6-fold higher in bones from fractures of osteoporotic patients; the other four did not show any statistical differences between the two groups (31).

More recently, screening the serum levels of 139 patients (32), which included controls, osteopenic (with and without fractures), and osteoporotic (with and without fracture), for the presence of circulating miRNAs, found miR122–5p and miR-4516 to be present at significantly different levels between non-osteoporotic control, osteopenic, and osteoporosis patients. Specifically, miR-122–5p levels were much lower in osteoporosis patients compared with non-osteoporotic control and osteopenic patients. Similarly, miR-4516 levels from osteoporotic patients were decreased compared to those of the non-osteoporotic control and osteopenic patients. Moreover, the levels of miR-4516 were significantly lower in osteoporotic patients with fracture compared to those without. The authors suggested that their results indicate that the decreasing levels of miR-122–5p and miR-4516 in clinical samples might be associated with the development of osteoporosis (32).

A final clinical study specifically investigated the serum levels of miRNAs in osteopenic, osteoporotic, and osteoporotic-associated fractures in postmenopausal Mexican women (33). Screening the expression of 754 miRNAs, the authors found that seven miRNAs (miR-23b-3p miR-140–3p, miR-885–5p, miR-17–5p, miR-1227–3p, miR-139–5p, and miR-197–3p) were significantly upregulated in the osteoporotic group. Further analyses showed that miR-23b-3p and miR-140–3p were significantly upregulated in osteoporotic, osteopenic, and osteoporotic-associated fracture groups while miR-885–5p levels only significantly increased in the osteopenic group, leading the authors to conclude that miR-23b-3p and miR-140–3p can serve as biomarker candidates for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women (33).

Animal Studies

In addition to these clinical studies, several animal miRNA profiling experiments have been reported. Using a model of periosteal cauterization in rats (which results in an atrophic nonunion), Waki et al., used microarrays to identify five miRNAs (miR-31a-3p, miR-31a-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-146b-5p and miR-223–3p) as highly upregulated in nonunion and verified these data by PCR analysis that showed their expression peaked on post fracture (PF) day 14 and declined by day 28 (34). Using the same approach, the same laboratory reported nine highly expressed miRNAs (miR-181d-5p, miR-181a-5p, miR-140–5p, miR-451a, miR-208b-3p, miR-743b-5p, miR-879–3p, miR-140–3p) present in the first 14 days following fracture. Further expression analysis by PCR indicated that miR-140–3p, miR-140–5p, miR-181a-5p, miR-181d-5p, and miR-451a were differentially expressed between normal fracture repair and nonunion at various points during the 28-day period (35).

In a more comprehensive analysis of miRNA expression (via microarray of 1881 mouse miRNAs) during the initial 14 days of physiological fracture repair, our laboratories used the standard femoral transverse fracture mouse model and bioinformatic analyses and reported that 922 miRNAs displayed differential expression. Of the 922 miRNAs, 306 and 374 were up and down-regulated, respectively, in the calluses in comparison to intact bone. Also, 20 miRNAs displayed both an up and down-regulated expression within the time course (post-fracture days 1–14) and the remaining 222 miRNAs did not exhibit any changes between the two samples. Six miRNAs (miR-140–3p, miR-21a-5p, miR-214–3p, miR-142a-3p, miR-3960, and miR-494–3p) were further analyzed by quantitative PCR and three were found to be upregulated (miR-140–3p, miR-21a-5p, and miR-214–3p), while the other three (miR-142a-3p, miR-3960, and miR-494–3p) were down regulated during fracture repair, validating the microarray data (36). Profiling aged female mice with transverse femoral fractures, He et al., reported that 53 miRNAs were significantly differentially expressed and another 11 novel miRNAs were associated with impaired fracture healing at 2- or 4-weeks post-fracture (37). The key findings from both clinical and animal profiling studies described in this section are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

miRNA profiling, identification, and expression in clinical and animal studies.

| Condition/Model | miRNAs | Observed Expression | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Studies | |||

| Osteoporotic fractures | miR-21, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-93, miR-100, miR-122a, miR-124a, miR-125b, miR-148a miR-21, miR-23a, miR-24, miR-25, miR-100, and miR-125b |

Significantly upregulated in serum Significantly upregulated in bone |

(29) |

| Osteoporotic fractures | miR-10a-5p, miR-10b-5p, miR-133b, miR-22–3p, miR-328–3p, and let-7g-5p | Significantly upregulated in serum | (30) |

| Osteoporotic fractures | miR-187 miR-518f |

Significantly downregulated in bone Significantly upregulated in bone |

(31) |

| Osteoporotic fractures | miR-122–5p, miR-4516 | Significantly downregulated in serum | (32) |

| Osteoporotic fractures | miR-23b-3p miR-140–3p, miR-885–5p, miR-17–5p, miR-1227–3p, miR-139–5p and miR-197–3p | Significantly upregulated in serum | (33) |

| Animal Studies | |||

| Rat atrophic nonunion | miR-31a-3p, miR-31a-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-146b-5p and miR-223–3p | Significantly upregulated in nonunion callus | (34) |

| Rat atrophic nonunion | miR-140–3p, miR-140–5p, miR-181a-5p, miR-181d-5p, and miR-451a | Significantly downregulated in nonunion callus | (35) |

| Mouse femoral transverse fracture | miR-140–3p, miR-21a-5p, miR-214–3p miR-142a-3p, miR-3960, miR-494–3p |

Significantly upregulated in callus Significantly downregulated in callus |

(36) |

| Mouse femoral transverse fracture | miR-206, miR-181b, miR-199a-5p, miR-125a-5p, miR-24, miR-497, miR-195, miR-23b, let-7e, miR-223 miR-494, miR-139–5p, miR-142–5p, miR-223, miR-144, miR-22, miR-494, miR-125a-3p, miR-144 |

Upregulated in callus Downregulated in callus |

(37) |

miRNA polymorphisms and human fractures

In addition to profiling studies, researchers have begun to report on the association of miRNA polymorphisms with clinical fractures. For example, one study focused on the effect of miR-124–3p expression levels in 195 patients with metaphyseal fractures of the distal tibia (38). Specifically, the study investigated the presence of the genotype of rs531564 (a single nucleotide polymorphism [SNP], site in pri-miR-124) by dividing the patients into two groups by the genotypes, GG (n=124) and GC+CC (n=71), and found that miR-124–3p expression was significantly increased in the GG group compared to the GC and CC groups. Further, the study showed experimentally that BMP-6 was a target gene for miR-124–3p. More importantly, BMP-6 mRNA and protein expression levels were significantly decreased in the GG group compared with GC and CC groups, confirming a negative regulatory relationship between miR-124–3p and BMP-6. The results suggest that the rs531564 miRNA-124–3p polymorphism may serve as a biomarker for metaphyseal distal tibia fractures (38).

Similarly, a case–control association study was conducted in order to determine the link between miR-146a, miR-149, miR-196a2, and miR-499 (based on previous reports of their effects on skeletal cells) polymorphisms and osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture (OVCF) susceptibility (39). A total of 286 unrelated postmenopausal Korean women (57 with OVCFs, 55 with non-OVCFs, and 174 healthy controls) were recruited and four SNPs from pre-miRNA sequences miR-146aC>G (rs2910164), miR-149T>C (rs2292832), miR-196a2T>C (rs11614913), and miR-499A>G (rs3746444) were examined. The results showed that: 1) the TT genotype of miR-149aT>C was less frequent in subjects with OVCFs, suggesting a protective effect against OVCFs; 2) the miR-146aCG/miR-196a2TC combined genotype was more frequent in OVCF patients, suggested an increase in OVCF risk; and 3) combinations of miR-146a, miR-149, miR-196a2, and miR-449 showed a significant association with increased prevalence of OVCFs in postmenopausal women, especially with the miR-146aG/miR-149T/miR-196a2C/miR-449G allele combination, which was significantly associated with an increased risk of OVCF. As such, the authors concluded that the TT genotype of miR-149aT>C may contribute to a decreased susceptibility to OVCF while the miR-146aCG/miR-196a2TC combined genotype and the miR-146aG/miR-149T/miR-196a2C/miR-449G allele combination may contribute to increased susceptibility to OVCF in Korean postmenopausal women (39).

While the last two studies focused on SNPs of pre-miRNA sequences, a slightly different approach was taken by the next study; how the rs1056629 in the 3’UTR of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) compromises its interaction with miR-491 in the control of pressure ulcers (PU) after hip fracture (40). Data obtained from 40 patients (22 subjects suffering from PU and a hip fracture and 18 healthy controls) indicated that MMP9 mRNA in patients with PU and hip fractures was greater than the controls and higher in individuals with an AA genotype rather than AC or CC. This suggests that the interaction between miR-491 and MMP9 could be disrupted by the presence of the minor allele of the rs1056629 polymorphism. Additional in vitro experiments showed the negative effects of miR-491 mimics on MMP9 levels and in reverse with a miR-491 inhibitor. Collectively, these data intimate that the rs1056629 polymorphism could serve as a biomarker for predicting the occurrence of PU after hip fracture (40).

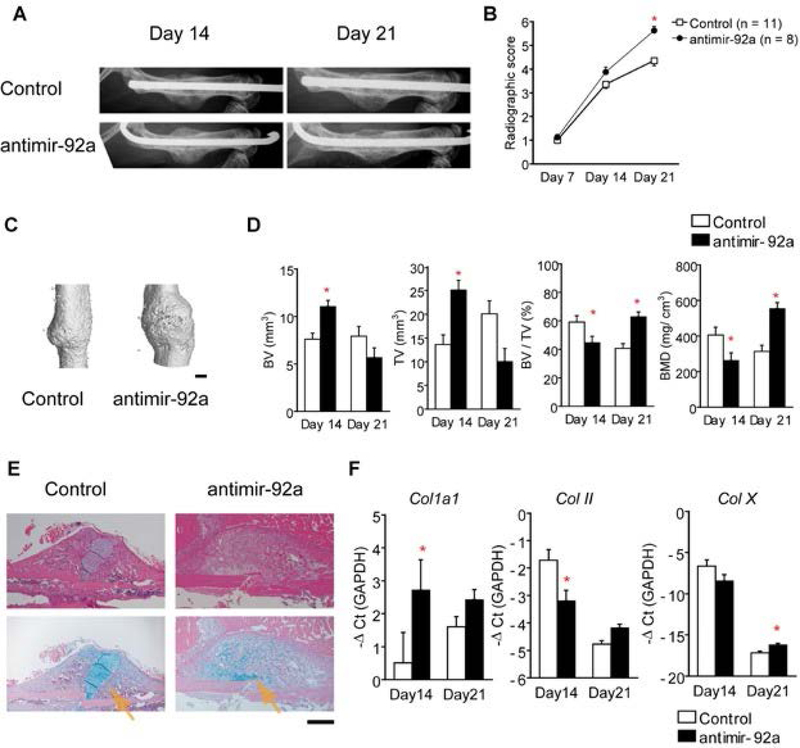

miRNAs and fracture repair

While the aforementioned studies were descriptive in nature, other studies were conducted that focused on specific miRNAs in order to elucidate their functional contribution during fracture repair. The earliest study was conducted by Murata et al., (41) where they combined a profiling approach with the functional characterization of one of the identified miRNAs. Specifically, the authors showed the presence of 134 miRNAs in plasma from four patients with trochanteric fractures as compared to four healthy controls. Moreover, they also showed that the levels of six miRNAs (miR-16, miR-19b-1, miR-25, miR-92a, miR-101, and miR-129–5p) were dysregulated. Using systemic downregulation of miR-92a (via antimir-92a) in a mouse femoral fracture model, the authors found increased callus volume and neovascularization that resulted in enhanced fracture repair (Figure 3) (41). Sun et al., (42) engineered miR-21 overexpressing bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) and injected these cells into the fracture site of rat transverse femoral fractures. At 7 days post-fracture they observed accelerated endochondral ossification, greater bone volume, and ultimately a biomechanically stronger bone. Given their data, the authors suggested that this may be a potential therapeutic approach to enhance fracture repair (42).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of miR-92a enhanced endochondral bone formation in mice with a femoral fracture. An antisense oligonucleotide to miR-92a (antimir-92a) or a scrambled control were delivered into mice with a femoral fracture intravenously on days 0 and post-fracture days 4, 7, 11, and 14. (A) Radiological images of the femurs at post-fracture days 14 and 21. (B) Radiographic score from x-ray images indicating bone formation. (C) Representative 3D mCT image of a fractured femur on post-fracture day 14. Scale bar = 1 mm. (D) TV and BV of the callus, BV/TV, and BMD on post-fracture day 14 and 21. (E) Histology of the fracture callus stained by HE or HE/Alcian-blue from post-fracture day 14. Arrows indicate Alcian-blue–positive cartilage. Scale bar = 500μm. (F) Callus mRNA levels of Col1a1, Col II, and Col X from post-fracture day 14 and 21 as determined by qRT-PCR. The data are shown as mean±SEM. *p<0.05. Adopted Murata et al. (41) with permission.

As miR-29b is known to promote osteoblast differentiation through the direct downregulation of inhibitors such HDAC4 (histone deacetylase 4), TFG-β3 (Transforming Growth Factor β3), ACVR2A (Activin A Receptor Type 2A), CTNNBIP1 (Catenin Beta Interacting Protein 1), and DUSP2 proteins (Dual Specificity Phosphatase 2) (43), Lee et al., (44) decided to examine its functional contribution to fracture repair. Using the mouse femoral transverse fracture model, the authors demonstrated that even a single injection of miR-29b-3p expressing plasmids (enclosed in microbubbles followed by ultrasound to destroy the microbubbles) two weeks after fracture led to a significant decrease of callus width and area at 4–6 weeks in comparison to no treatment or repeated treatment indicating acceleration of repair. Callus microCT measurements verified these results by showing that miR-29b-3p overexpression significantly increased callus bone volume and bone mineral density (BMD). Lastly, biomechanical testing of the fractured femurs at 6 weeks post-fracture showed significant increases in stiffness (44). Collectively, the data supports the notion that miR-29b-3p is capable of accelerating fracture repair.

miR-222 is known to be a negative regulator of angiogenesis (45), a process critical to successful fracture repair. In conjunction with a rat femoral transverse fracture and cauterization of the periosteum at the fracture site, a miR-222 inhibitor and mimic, were each tested (along with a non-functional inhibitor negative control) for their effects on fracture repair (46). Initially, the miR-222 inhibitor, mimic, and negative control, was mixed with atelocollagen and administered into the fracture site (immediately after fracture). By 8 weeks post-fracture, significant bone union was only achieved with the miR-222 inhibitor, as seen with both radiographs and microCT. These data were supported by measurements of callus capillary density (at 2 weeks post-fracture) that showed a doubling of vessels with the inhibitor, indicating that angiogenesis and subsequently fracture repair can be enhanced by downregulating miR-222 (46).

Based on previous data showing miR-142–5p expression increases during the osteoblast differentiation and mineralization (47), Tu et al., (48) utilized a mouse femoral transverse fracture model and showed that lower expression of miR-142–5p in the callus of aged mice than those of young mice and that these results directly correlated with the age-related delay in fracture repair. Further experiments with periosteal injection (once a week for 4 weeks) of either agomir-142–5p or negative control agomir at the fracture site of aged mice showed significant increases in Runx2 and osteocalcin protein expression, along with increased callus BMD for the agomir-142–5p treatment, indicating enhanced osteoblastic activity and overall improved fracture repair (48).

Yet another miRNA that is linked to osteogenesis was tested for its role in fracture repair. Using the same approach previously reported for miRNA overexpressing BMSCs (42), Shi et al., (49) investigated whether miR-218 can have an impact on fracture repair. Specifically, when injected at the fracture site of mouse femoral transverse fractures, miR-218 overexpressing cells significantly increased bone volume at 2 and 4 weeks post-fracture in comparison to the control group. Statistically significant increases in Osterix and Osteocalcin protein expression, as determined by immunohistochemistry, were also observed in the experimental group at the same time points. Moreover, the biomechanical properties (ultimate load and energy to failure) of the fractured bone, were also significantly increased in the presence of the miR-218 overexpressing BMSCs, leading the authors to conclude that miR-218 is a promising therapeutic target for fracture repair (49).

A more recent study sought to examine the link between miRNA-148a and one of its target genes, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) (50). After establishing via in vitro experiments that IGF1 is indeed a target of miR-148a, an in vivo study was conducted using the rat femoral transverse fracture model. Following fracture, groups of rats received either: a) BMSCs transfected with miR-148a agomir or the IGF1 gene; b) a blank group that received no cells; c) a negative control group that received normal BMSCs; and d) another group that received both, miR-148a agomir and IGF1 BMSCs that were cotransfected with miR-148a agomir and the IGF1 gene. Results over a 6-week period following fracture and injections showed enhanced fracture repair in the IGF group, characterized by decreased callus width and area, higher BMD, and increased biomechanical strength (maximum load, stiffness, and energy absorption). In contrast, the animals groups with the miR-148a agomir or the combination of miR-148a agomir and IGF1 showed delayed healing, indicating that decreasing the expression of miR-148a could improve fracture healing by reducing the silencing of IGF1 (50).

The link between miR-185, PTH, and Wnt signaling was explored using a mouse femoral transverse fracture model to obtain primary osteoblasts for testing in vitro (51). In these fractured bone-derived osteoblasts, PTH was established as a target of miR-185 using a series of mimics or inhibitors. Data were also presented showing that in osteoblasts transfected with miR-185 mimics or siRNA against PTH resulted in decreased levels of PTH, β-catenin, and Wnt5b, indicating that miR-185 blocks the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by inhibiting PTH. Further, miR-185 inhibitors stimulated osteoblast viability and reduced apoptosis, with more cells arrested at G1. In contrast, miR-185 mimics had inhibitory effects on osteoblasts, therefore supporting that idea that suppression of miR-185 targeting PTH could positively regulate osteoblast activity during fracture repair through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. (51). Key findings from all of the studies described in this section are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

miRNA functional data during fracture repair. These studies either increased or decreased individual miRNAs levels.

| Model | Target miRNA | Observed Results | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse femoral transverse fracture | ↓miR-92a | Increased callus volume and neovascularization | (41) |

| Rat transverse femoral fracture | ↑miR-21 | Accelerated endochondral ossification; greater bone volume; increased ultimate load and energy to failure | (42) |

| Mouse femoral transverse fracture | ↑miR-29b-3p | Decreased callus width and area; increased callus bone volume and density; increased stiffness | (44) |

| Rat transverse femoral fracture and cauterization of the periosteum | ↓miR-222 | Bone union; Increased callus capillary density | (45) |

| Mouse femoral transverse fracture | ↑miR-142–5p | Increased Runx2 and osteocalcin expression; increased callus bone mineral density | (48) |

| Mouse femoral transverse fracture | ↑miR-218 | Increased Osterix and Osteocalcin expression; bone volume; increased ultimate load and energy to failure | (49) |

| Rat transverse femoral fracture | ↑miR-148a | Decreased callus width and area; higher bone mineral density; increased biomechanical strength (maximum load, stiffness, and energy absorption) | (50) |

| Mouse femoral transverse fracture | ↑miR-185 | In fracture bone-derived osteoblasts: decreased levels of PTH, β-catenin and Wnt5b; stimulated osteoblast viability; reduced apoptosis with more cells arrested at G1 | (51) |

miRNAs in bone defects

Although, it is not within the direct scope of this review, miRNA delivery using a variety of biomaterials has also shown preclinical success in treating critical size bone defects (not fractures by nature, but their repair involves bone regeneration). Briefly, use of miR-31- knockdown modified adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) in β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) scaffolds implanted in rat critical-sized calvarial defects dramatically improved bone repair by increasing bone volume and BMD (52). In a follow up study, Deng et al., (53) showed that miR-31-modified BMSCs seeded on poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) scaffolds were able to repair 8 mm critical-size rat calvarial defects by significantly increasing bone formation. Li et al., (54) explored the effects of suppressing miR-214 in an osteoporotic rat model with a critical-size bone defect at the femoral metaphysis. The approach consisted of allotransplantation of BMSCs from ovariectomized (OVX) rats that over-expressed miR-214. Application of these miR-214 expressing engineered cells in sponges healed the bone defect and enhanced bone quality (as determined by measurements of bone volume, density, trabecular number, thickness and space) at 4 weeks post-implantation (54). Qureshi et al., (55) used a mimic of miR-148b tethered to silver nanoparticles, that when added to ASCs and loaded onto either Matrigel or polycaprolactone (PCL) scaffolds, resulted in different levels of healing of critical size defects in the right parietal bone of male CD-1 nude homozygous mice (55). Similarly, when modified miR-26a overexpressing ASCs were incorporated into porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds, they improved repair of rat tibial defects (56).

Using an innovative approach, Zhang et al., (57) generated miR-26a containing microspheres that were attached to cell-free nanofibrous polymer scaffolds that spatially controlled the release of miR-26a. Specifically, it showed ectopic bone formation subcutaneously, as well as repair of mouse critical-sized calvarial defects with increased bone volume and BMD (57). Another study generated transgenic mice overexpressing miR-355–5p, and when BMSCs from these mice were incorporated in a silk fibroin scaffold and implanted in a mouse critical-sized calvarial defect, significant increases were observed in bone volume in comparison to those using wild-type BMSCs (58). The same laboratory also used a lipidoid-miRNA formulation of miR-335–5-p to demonstrate increased repair of a mouse critical-sized calvarial defect (59). Finally, Hu et al., (60) used a miR-210–3p/poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA)/BMSCs constructs to induce ectopic bone formation. More importantly, they also showed enhanced repair of canine mandibular bone defects with significant increases in bone volume and density, as well as trabecular thickness and number, indicating that this miRNA-based strategy can serve as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of bone defects (60). Key findings from all of the studies described in this section are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

miRNAs in bone defects. These studies either increased or decreased individual miRNAs levels.

| Model | Target miRNA | Observed Results | Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat critical-sized calvarial defects | ↓miR-31 | Increased bone volume and mineral density | (52,53) |

| Rat critical-size femoral metaphysis defect | ↑miR-214 | Increased bone volume, mineral density, trabecular number and thickness; decreased trabecular space | (54) |

| Mouse critical-sized calvarial (parietal) defects | ↑miR-148b | Increased bone regrowth | (55) |

| Rat tibial defects | ↑miR-26a | Increased bone formation | (56) |

| Mouse critical-sized calvarial defects | ↑miR-26a | increased bone volume and mineral density | (57) |

| Mouse critical-sized calvarial defects | ↑miR-355–5p | Increased bone volume | (58,59) |

| Subcutaneously transplanted Canine mandibular bone defect |

↑miR-210–3p | Ectopic bone formation Increased bone volume and density; increased trabecular thickness |

(60) |

miRNAs in exosomes

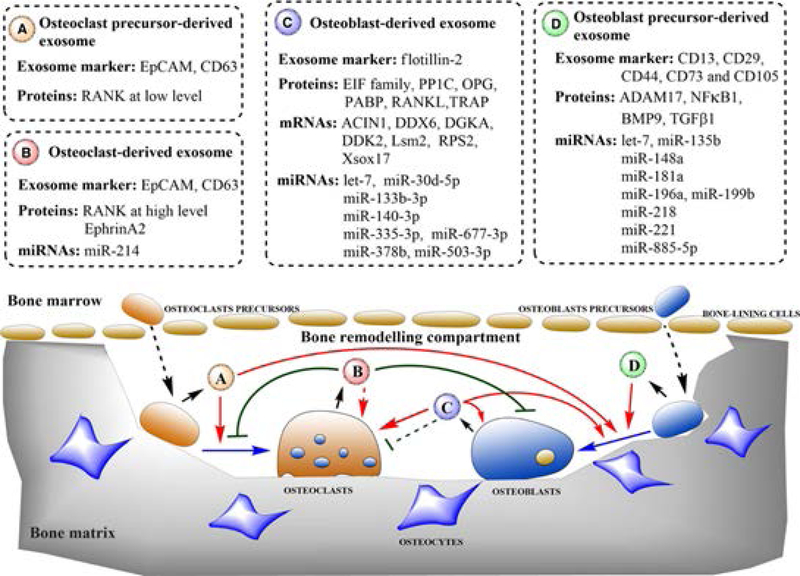

Within the last few years, exosome analysis has become an active area of research. Exosomes are nano-sized (40–100nm) membrane-bound vesicles that are released by a variety of cells. Exosome contents include membrane and cytosolic proteins, as well as nucleic acids, including miRNAs. Importantly, exosomes can deliver their cargo to secondary cells, thereby affecting the recipient cells’ cellular activities (61, 62). Several published reports describe some of our current knowledge of exosome miRNAs and their relationship to the skeletal system (63–66). For example, Xie et al., (63) focused exclusively on exosome miRNAs involved in bone remodeling and described their function in regulating differentiation and communication of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Specifically, they showed which specific miRNAs are present in exosomes released by osteoclast precursors, osteoclasts, osteoblast precursors, and osteoblasts (Figure 4). Data also showed the expression levels of each miRNA, their target gene and function. It is worth mentioning that four of the miRNAs (miR-140–3p, miR-148a, mir-218, and miR-214), previously discussed in the context of fracture repair, are also listed as involved in bone remodeling. For example, miR-140–3p was found in osteoblast-derived exosomes and in osteoblastic MC3T3 cells, and has been shown to promote osteoblast differentiation (67). Additionally, miR-148a and miR-218 were found in osteoblast precursor exosomes and in human BMSCs where the former promotes osteoclastogenesis (68) and the latter enhances osteoblast differentiation (69). Lastly, miR-214–3p is found in osteoclast derived exosomes and inhibits osteoblastic bone formation (Figure 4) (70).

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram showing the roles of bone cell derived exosomes. Osteoclast precursor-derived exosomes (A) stimulate differentiation of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Osteoclast-derived exosomes (B) reduce the osteoclast number and osteoblastic bone formation. Osteoblast-derived exosomes (C) promote differentiation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts and establish a positive feedback in bone growth. Osteoblast precursor-derived exosomes (D) induce MSCs to differentiate into osteoblasts. Boxes indicate the primary contents of bone-derived exosomes involved in bone remodeling. Short black arrows indicate the secretion process. Dotted black arrows indicate the translocation of cells. Solid blue arrows indicate cell differentiation. Solid red arrows and green lines indicate the activation and inhibition of cellular processes, respectively. Dotted lines indicate unclear mechanisms. Adopted by Xie et al., (63) with permission.

In a direct investigation of exosomes and fracture repair, Furuta et al., (66) examined the role of exosomes isolated from MSC-conditioned medium in conjunction with a mouse femoral transverse fracture model of CD9−/− mice (known to produce reduced levels of exosomes). While the wild-type CD9+/+ mice exhibited endochondral ossification of the callus at 2 weeks and bony union at 3 weeks post-fracture, the CD9−/− mice showed only a 25% union rate at 3 weeks. Moreover, injection of MSC-derived exosomes into the fracture site of CD9−/− mice resulted in abundant callus formation at 2 weeks and bony union at 3 weeks post-fracture, corresponding to that of CD9+/+ mice and demonstrating that exosomes rescued the delayed fracture repair. Similarly, injected MSC-derived exosomes at the fracture site of wild-type mice enhanced fracture repair. Finally, molecular analysis of MSC exosomes revealed the presence of several highly expressed miRNAs (66), including miR-29b-3p, which significantly increased callus bone volume and density (44). Clearly, exosomes with their cargo miRNAs are key components of the fracture repair process that are just beginning to be understood.

It is worth mentioning that two relatively recent studies using exosomes have also demonstrated their therapeutic potential in bone defect healing. Qi et al., (71) incorporated human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived exosomes within β-TCP scaffolds, hiPSC-MSC-Exos, and implanted them into critical size calvarial defects in ovariectomized rats. The results showed significant increases in bone area, volume and density in comparison to the controls (β-TCP scaffold without exosomes). This increase was accompanied by a robust angiogenic response, with large significant increase in blood vessel area and numbers. Taken together, results indicate the hiPSC-MSC-Exos delivered within β-TCP scaffolds enhanced angiogenesis and osteogenesis leading to robust bone regeneration in critical-sized calvarial defects (71). Lastly, using a similar approach of exosomes derived from hiPSC-MSCs, β-TCP scaffolds, and a critical size calvarial defect model, Zhang et al., (72) also showed significant increases in bone area, volume, and density indicative of enhanced bone regeneration. A comparison of the expression and function of exosomal and free miRNAs is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Expression and function comparison between free and exosomal miRNAs.

| miRNA | Free Expression (Study) | Exosomal Expression (Study) |

|---|---|---|

| miR-140–3p | Serum from osteoporotic fracture patients – Upregulated (33) Callus from rat nonunion fractures – Downregulated (35) Callus from mouse transverse fractures – Upregulated (36) |

Osteoblast-derived – Promotes osteoblast differentiation (67) |

| miR-148a | Serum from osteoporotic fracture patients – Upregulated (29) | Osteoblast precursors – Promotes osteoclastogenesis (68) Human BMSCs – Enhances osteoblast differentiation (69) |

| miR-218 | Overexpressing BNSCs – Enhances mouse fracture healing (49) | Osteoblast precursors – Promotes osteoclastogenesis (68) Human BMSCs – Enhances osteoblast differentiation (69) |

| miR-214 | Overexpressing BMSC – Enhances rat bone defect healing (54) Femoral head trabecular bone from patients with osteoporotic hip fractures – Upregulated (31) |

Osteoclast-derived – Inhibits bone formation (70) |

| miR-29b-3p | Plasmids expression – Enhances mouse fracture healing (44) | MSC-derived – Enhances mouse fracture repair (66) |

miRNAs as therapeutic orthobiologics

Given the regulatory nature of miRNAs as well as the plethora of data that supports their functional contribution to many aspects of the mammalian skeletal system, including its repair following fractures, we are at the point where we should be more actively pursuing clinical applications for these small RNA molecules. The potential of miRNAs becoming the next orthobiologic target is high. However, the question remains, how best to target them in vivo at a specific tissue/organ or cell type? Obviously, this is a complex and challenging task. Simplistically thinking, there are two modes of therapy, either inhibition or replacement of miRNAs. As miRNAs are nucleic acids, we are not strangers to this area of research since we have been silencing or overexpressing genes with varying degrees of success for decades. In regards to utilizing miRNA as therapeutics for fracture repair, Scimeca and Verron (73), proposed three broad areas: 1) identifying the target miRNA and deciding whether we should increase or decrease its expression; 2) designing miRNA replacement or inhibition approaches; and 3) delivering miRNAs by taking into consideration the type of scaffold to use (if any), transfection efficiency, and specificity. Although, major obstacles remain in all three major areas, advances are reported and are expected to continue given our knowledge and ability surrounding successful therapeutic applications of targeting nuclei acids in general.

Identifying which miRNAs to target solely depends on our knowledge of their function presented in published reports and verified by several laboratories. Based on the aforementioned studies in profiling of fracture repair (34–37), there are potentially hundreds of miRNAs that display differential expression during the process. The field is certainly ripe for harvesting, but the primary task is to functionally characterize them. Recently, we have seen some progress in this area with reports identifying the functional significance of individual miRNAs in enhancing fracture repair, as was summarized herein and in various brief review articles (73–76). Clearly, utilizing already characterized miRNAs is a valid starting point and again, Scimeca and Verron (73) classify miRNAs in various functional categories, including, bone homeostasis (bone formation and resorption) and bone pathologies (osteoporosis, fractures, cancer, and even osteogenesis and angiogenesis). As such, we are beginning to amass functional categories of characterized miRNAs that should serve as good starting point for selection (77).

Designing therapeutic miRNA replacement or inhibition approaches is not trivial and one of the biggest obstacles is off-target effects since individual miRNAs are pleiotropic in nature. Obviously, off-target effects can lead to adverse effects in other tissues and organs, especially if the therapeutic application is systemic; even though this approach also has hurdles from miRNA mimic or inhibitor degradation by abundant nucleases present in the plasma and extracellular environment, as well as removal from the circulation by the liver and kidneys (78). One way to avoid off-target effects is administration of the miRNA mimic or inhibitor locally or with the use of a scaffold. This certainly builds on our knowledge of nanomedicine and tissue engineering, especially in the formulation of site-specific delivery systems as well as biomaterials. In fact, this approach can be built off findings on bone regeneration therapies, some of which were described in previous sections of this review. Thus, the need to develop delivery systems that can perturb function locally, reducing the possibility of off-target effects.

To this end, tissue engineers have been at the forefront of the field. There are many different types of delivery systems that tissues engineers have been using for many years to locally deliver nucleic acids, proteins, drugs, and cells in order to induce tissue regeneration. In fact, this approach has also been tested with miRNA delivery therapeutically as described previously in this report. Specifically, electrospun scaffolds, chitosan, calcium phosphate, silver nanoparticles, and polymeric hydrogels were used as miRNA-delivery based scaffolds for a variety of advantages (73). There are many other scaffold types and biomaterials that can be used given their wide utilization in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Additionally, a question remains whether the miRNA should be in a carrier or not. Obviously, naked nucleic acids can be easily degraded and therefore need to be protected. Many different viral and non-viral carriers exist that can be used to protect, deliver, and increase the transfection efficiency of miRNA based therapeutics (79). From the early days of gene therapy, we know the advantages and disadvantages of each type. While viral vectors are the gold standard in providing the greatest transfection efficiencies, production of high expression of the transgene and to induce stable transfection, they suffer from safety, toxicity, high cost, difficulty in production, and can be immunogenic (78). In contrast, non-viral vectors are safe and non-toxic, but they suffer from low transfection efficiencies (80). Recently though, we have seen increases in transfection efficiencies with the use of lipid-based carriers, polymeric based carriers, nanoparticles, peptides, inorganic materials, etc. (81). Lastly, engineering stem cells with high levels of miRNA expression may be yet another approach of local delivery as was demonstrated by studies described above (58–60). Clearly, we have a variety of options that can be used to successfully and effectively deliver miRNA-based therapeutics locally and safely.

Concluding Remarks

Despite the aforementioned challenges, experimental improvements have been achieved and now there are several miRNA-based pharmaceutics that have entered clinical trials. Although the majority of them are in Phase I clinical trials, a couple have advanced into Phase II. These are compounds SPC3649 (miravirsen) and RG-101, both inhibitors of miR-122 developed by Santaris Pharma and Regulus Therapeutics, respectively, for the treatment of hepatitis C (78, 82). Similarly, the number of issued patents and biopharmaceutical companies involved in RNA based therapies has also increased in the past several years (82). And even though, miRNA bone-based therapies lag behind those of other tissues (e.g. cardiac; vascular and a variety of cancers) and even chronic wound healing (83), we are optimistic that in the near future we will see the use of miRNAs, as a diagnostic tool for bone related disorders like osteoporosis (84), osteoarthritis (85) or the prevention and treatment of bone pathologies (86). More importantly, miRNA-based orthobiologics will undoubtedly enhance the angiogenic, chondrogenic and osteogenic potential of a fractured bone (including delayed and non-unions), thereby accelerating its ability to heal and return the patient back to normal health. As such, miRNAs represent the next generation of orthobiologics.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledges the financial support by a grant, R15HD092931 (MH), from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Hadjiargyrou M, O’Keefe RJ. The convergence of fracture repair and stem cells: interplay of genes, aging, environmental factors and disease. J Bone Miner Res 2014. 29(11):2307–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadjiargyrou M, Lombardo F, Zhao S, et al. Transcriptional profiling of bone regeneration. Insight into the molecular complexity of wound repair. J Biol Chem 2002;277(33):30177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duchamp de Lageneste O, Julien A, Abou-Khalil R, Frangi G, Carvalho C, Cagnard N, Cordier C, Conway SJ, Colnot C. Periosteum contains skeletal stem cells with high bone regenerative potential controlled by Periostin. Nat Commun 2018. 9(1):773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bragdon BC, Bahney CS. Origin of Reparative Stem Cells in Fracture Healing. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2018. 16(4):490–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komatsu DE, Hadjiargyrou M. Activation of the transcription factor HIF-1 and its target genes, VEGF, HO-1, iNOS, during fracture repair. Bone 2004. 34(4):680–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Komatsu DE, Bosch-Marce M, Semenza GL, Hadjiargyrou M Enhanced bone regeneration associated with decreased apoptosis in mice with partial HIF-1alpha deficiency. J Bone Miner Res 2007. 22(3):366–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan C, Gilbert SR, Wang Y, Cao X, Shen X, Ramaswamy G, Jacobsen KA, Alaql ZS, Eberhardt AW, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA, Deng L, Clemens TL Activation of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha pathway accelerates bone regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008. 105(2):686–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kusumbe AP, Ramasamy SK, Adams RH. Coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis by a specific vessel subtype in bone. Nature 2014. 507:323–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saran U, Gemini Piperni S, Chatterjee S. Role of angiogenesis in bone repair. Arch Biochem Biophys 2014. 561:109–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong SA, Rivera KO, Miclau T 3rd, Alsberg E, Marcucio RS, Bahney CS. Microenvironmental Regulation of Chondrocyte Plasticity in Endochondral Repair-A New Frontier for Developmental Engineering. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2018. 6:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, Tsang KY, Tang HC, Chan D, Cheah KS. Hypertrophic chondrocytes can become osteoblasts and osteocytes in endochondral bone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014. 111(33):12097–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, von der Mark K, Henry S, Norton W, Adams H, de Crombrugghe B. Chondrocytes transdifferentiate into osteoblasts in endochondral bone during development, postnatal growth and fracture healing in mice. PLoS Genet 10(12):e1004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu DP, Ferro F, Yang F, Taylor AJ, Chang W, Miclau T, et al. Cartilage to bone transformation during fracture healing is coordinated by the invading vasculature and induction of the core pluripotency genes. Development 2017. 144:221–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schindeler A, McDonald MM, Bokko P, Little DG. Bone remodeling during fracture repair: The cellular picture. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2008. 19(5):459–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersson GBJ, Bouchard J, Bozic KJ, Campbell RM Jr, Cisternas MG, Correa A, Cosman F, Cragan JD, D’Andrea K, Doernberg N, Dormans JP, Elderkin AL, Fershteyn Z, Foreman AJ, Gitelis S, Gnatz SM, Haralson RH III, Helmick CG, Hu S, Katz JN, King T, Kirk R, Kurtz SM, Lane N, Miller A, Novich RL, Olney R, Panopalis P, Pasta DJ, Pollak AN, Puzas JE, Richards BS III, Sestito JP, Siffel C, Sponseller PD St., Clair EW, Stuart A, Templeton KJ, Thompson G, Tosi L, Ward WG Sr., Watkins-Castillo SI, Weinstein SL, Wright JG, Yelin EH. 2008. United States Bone and Joint Decade: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; pp 97–161. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis JR, Safford MM. Management of osteoporosis among the elderly with other chronic medical conditions. Drugs Aging 2012. 29:549–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonova E, Le TK, Burge R, Mershon J. Tibia shaft fractures: costly burden of nonunions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013. 14:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mabry TM, Prpa B, Haidukewych GJ, Harmsen WS, Berry DJ Long-term results of total hip arthroplasty for femoral neck fracture nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004. 86-A(10):2263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komatsu DE, Warden SJ. The control of fracture healing and its therapeutic targeting: improving upon nature. J Cell Biochem 2010. 109(2):302–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buza JA 3rd, Einhorn T. Bone healing in 2016. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2016. 13(2):101–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brosnan CA, Voinnet O. The long and the short of noncoding RNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2009. 21(3):416–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadjiargyrou M, Delihas N. The intertwining of transposable elements and non-coding RNAs. Int J Mol Sci 2013. 14(7):13307–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Treiber T, Treiber N, Meister G. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis and its crosstalk with other cellular pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2018. September 18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs”. Genome Research 2009. 19(1): 92–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartel DP. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell 2018. 173(1):20–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lekka E, Hall J. Noncoding RNAs in disease. FEBS Lett 2018. 592(17):2884–2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerlach CV, Vaidya VS. MicroRNAs in injury and repair. Arch Toxicol 2017. 91(8):2781–2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gennari L, Bianciardi S, Merlotti D. MicroRNAs in bone diseases. Osteoporos Int 2017. 28(4):1191–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seeliger C, Karpinski K, Haug AT, Vester H, Schmitt A, Bauer JS, van Griensven M. Five freely circulating miRNAs and bone tissue miRNAs are associated with osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2014. 29(8):1718–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weilner S, Skalicky S, Salzer B, Keider V, Wagner M, Hildner F, Gabriel C, Dovjak P, Pietschmann P, Grillari-Voglauer R, Grillari J, Hackl M. Differentially circulating miRNAs after recent osteoporotic fractures can influence osteogenic differentiation. Bone 2015. 79:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garmilla-Ezquerra P1, Sañudo C, Delgado-Calle J, érez-Nuñez MI, Sumillera M, Riancho JA Analysis of the bone microRNome in osteoporotic fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 2015. 96(1):30–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandourah AY, Ranganath L, Barraclough R, Vinjamuri S, Hof RV, Hamill S, Czanner G, Dera AA, Wang D, Barraclough DL. Circulating microRNAs as potential diagnostic biomarkers for osteoporosis. Sci Rep 2018. 8(1):8421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramírez-Salazar EG, Carrillo-Patiño S, Hidalgo-Bravo A, Rivera-Paredez B, Quiterio M, Ramírez-Palacios P, Patiño N, Valdés-Flores M, Salmerón J, Velázquez-Cruz R. Serum miRNAs miR-140–3p and miR-23b-3p as potential biomarkers for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture in postmenopausal Mexican-Mestizo women. Gene 2018. 679:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waki T, Lee SY, Niikura T, Iwakura T, Dogaki Y, Okumachi E, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Profiling microRNA expression in fracture nonunions: Potential role of microRNAs in nonunion formation studied in a rat model. Bone Joint J 2015. 97-B(8):1144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waki T, Lee SY, Niikura T, Iwakura T, Dogaki Y, Okumachi E, Oe K, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Profiling microRNA expression during fracture healing. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016. 17:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hadjiargyrou M, Zhi J, Komatsu DE. Identification of the microRNA transcriptome during the early phases of mammalian fracture repair. Bone 2016. 87:78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He B, Zhang ZK, Liu J, He YX, Tang T, Li J, Guo BS, Lu AP, Zhang BT, Zhang G. Bioinformatics and Microarray Analysis of miRNAs in Aged Female Mice Model Implied New Molecular Mechanisms for Impaired Fracture Healing. Int J Mol Sci 2016. 17(8) pii: E1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zou L, Zhang G, Liu L, Chen C, Cao X, Cai J. A MicroRNA-124 Polymorphism is Associated with Fracture Healing via Modulating BMP6 Expression. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;41(6):2161–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahn TK, Kim JO, Kumar H, Choi H, Jo MJ, Sohn S, Ropper AE, Kim NK, Han IB. Polymorphisms of miR-146a, miR-149, miR-196a2, and miR-499 are associated with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures in Korean postmenopausal women. J Orthop Res 2018. 36(1):244–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang R, Han L, Zeng X. A functional polymorphism at miR-491-5p binding site in the 3’UTR of MMP9 gene confers increased risk for pressure ulcers after hip fracture. Oncol Rep 2018. 39(6):2695–2702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murata K, Ito H, Yoshitomi H, Yamamoto K, Fukuda A, Yoshikawa J, Furu M, Ishikawa M, Shibuya H, Matsuda S. Inhibition of miR-92a enhances fracture healing via promoting angiogenesis in a model of stabilized fracture in young mice. J Bone Miner Res 2014. 29(2):316–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, Xu L, Huang S, Hou Y, Liu Y, Chan KM, Pan XH, Li G. mir-21 overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells accelerate fracture healing in a rat closed femur fracture model. Biomed Res Int 2015. 2015:412327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Z, Hassan MQ, Jafferji M, Aqeilan RI, Garzon R, Croce CM, et al. Biological functions of miR-29b contribute to positive regulation of osteoblast differentiation. J. Biol. Chem 2009. 284(23):15676–15684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee WY, Li N, Lin S, Wang B, Lan HY, Li G. miRNA-29b improves bone healing in mouse fracture model. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2016. 430:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Targeting microRNA expression to regulate angiogenesis. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2008. 29(1):12–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshizuka M, Nakasa T, Kawanishi Y, Hachisuka S, Furuta T, Miyaki S, Adachi N, Ochi M. Inhibition of microRNA-222 expression accelerates bone healing with enhancement of osteogenesis, chondrogenesis, and angiogenesis in a rat refractory fracture model. J Orthop Sci 2016. 21(6):852–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao R, Zhu Y, Sun B. Exploration of the effect of mmumiR-142–5p on osteoblast and the mechanism. Cell Biochem Biophys 2015. 71:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tu M, Tang J, He H, Cheng P, Chen C. MiR-142–5p promotes bone repair by maintaining osteoblast activity. J Bone Miner Metab 2017. 35(3):255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi L, Feng L, Liu Y, Duan JQ, Lin WP, Zhang JF, Li G. MicroRNA-218 Promotes Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Accelerates Bone Fracture Healing. Calcif Tissue Int 2018. 103(2):227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu H, Su H, Wang X, Hao W. MiR-148a regulates bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-mediated fracture healing by targeting insulin-like growth factor 1. J Cell Biochem 2018. October 18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Yao CJ, Lv Y, Zhang CJ, Jin JX, Xu LH, Jiang J, Geng B, Li H, Xia YY, Wu M. MicroRNA-185 inhibits the growth and proliferation of osteoblasts in fracture healing by targeting PTH gene through down-regulating Wnt/β-catenin axis: In an animal experiment. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018. 501(1):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng Y, Zhou H, Zou D, Xie Q, Bi X, Gu P, Fan X. The role of miR-31-modified adipose tissue-derived stem cells in repairing rat critical-sized calvarial defects. Biomaterials 2013. 34(28):6717–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deng Y, Bi X, Zhou H, You Z, Wang Y, Gu P, Fan X. Repair of critical-sized bone defects with anti-miR-31-expressing bone marrow stromal stem cells and poly(glycerol sebacate) scaffolds. Eur Cell Mater 2014. 27:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li KC, Chang YH, Yeh CL, Hu YC. Healing of osteoporotic bone defects by baculovirus-engineered bone marrow-derived MSCs expressing MicroRNA sponges. Biomaterials 2016. 74:155–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qureshi AT, Doyle A, Chen C, Coulon D, Dasa V, Del Piero F, Levi B, Monroe WT, Gimble JM, Hayes DJ. Photoactivated miR-148b-nanoparticle conjugates improve closure of critical size mouse calvarial defects. Acta Biomater 2015. 12:166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Z, Zhang D, Hu Z, Cheng J, Zhuo C, Fang X, Xing Y. MicroRNA-26a-modified adipose-derived stem cells incorporated with a porous hydroxyapatite scaffold improve the repair of bone defects. Mol Med Rep 2015. 12(3):3345–3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang X, Li Y, Chen YE, Chen J, Ma PX. Cell-free 3D scaffold with two-stage delivery of miRNA-26a to regenerate critical-sized bone defects. Nat Commun 2016. 7:10376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Tang Y, Zhu X, Tu T, Sui L, Han Q, Yu L, Meng S, Zheng L, Valverde P, Tang J, Murray D, Zhou X, Drissi H, Dard MM, Tu Q, Chen J. Overexpression of MiR-335–5p Promotes Bone Formation and Regeneration in Mice. J Bone Miner Res 2017. 32(12):2466–2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sui L, Wang M, Han Q, Yu L, Zhang L, Zheng L, Lian J, Zhang J, Valverde P, Xu Q, Tu Q, Chen J. A novel Lipidoid-MicroRNA formulation promotes calvarial bone regeneration. Biomaterials 2018. 177:88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hu B, Li Y, Wang M, Zhu Y, Zhou Y, Sui B, Tan Y, Ning Y, Wang J, He J, Yang C, Zou D. Functional reconstruction of critical-sized load-bearing bone defects using a Sclerostin-targeting miR-210–3p-based construct to enhance osteogenic activity. Acta Biomater 2018. 76:275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yu X, Odenthal M, Fries JW. Exosomes as miRNA Carriers: Formation-Function-Future. Int J Mol Sci 2016. 17(12). pii: E2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Daly M, O’Driscoll L. MicroRNA Profiling of Exosomes. Methods Mol Biol 2017. 1509:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie Y, Chen Y, Zhang L, Ge W, Tang P. The roles of bone-derived exosomes and exosomal microRNAs in regulating bone remodelling. J Cell Mol Med 2017. 21(5):1033–1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hao ZC, Lu J, Wang SZ, Wu H, Zhang YT, Xu SG. Stem cell-derived exosomes: A promising strategy for fracture healing. Cell Prolif 2017. 50(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Behera J, Tyagi N. Exosomes: mediators of bone diseases, protection, and therapeutics potential. Oncoscience 2018. 5(5–6):181–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Furuta T, Miyaki S, Ishitobi H, Ogura T, Kato Y, Kamei N, Miyado K, Higashi Y, Ochi M. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Promote Fracture Healing in a Mouse Model. Stem Cells Transl Med 2016. 5(12):1620–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fushimi S, Nohno T, Nagatsuka H, Katsuyama H. Involvement of miR-140–3p in Wnt3a and TGFβ3 signaling pathways during osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. Genes Cells 2018. 23(7):517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng P, Chen C, He HB, et al. miR-148a regulates osteoclastogenesis by targeting Vmaf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog B. J Bone Miner Res 2013. 28: 1180–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hassan MQ, Maeda Y, Taipaleenmaki H, et al. miR-218 directs a Wnt signaling circuit to promote differentiation of osteoblasts and osteomimicry of metastatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2012. 287: 42084–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li D, Liu J, Guo B, et al. Osteoclast-derived exosomal miR-214–3p inhibits osteoblastic bone formation. Nat Commun 2016. 7:10872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qi X, Zhang J, Yuan H, Xu Z, Li Q, Niu X, Hu B, Wang Y, Li X. Exosomes Secreted by Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Repair Critical-Sized Bone Defects through Enhanced Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis in Osteoporotic Rats. Int J Biol Sci 2016. 2(7):836–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang J, Liu X, Li H, Chen C, Hu B, Niu X, Li Q, Zhao B, Xie Z, Wang Y. Exosomes/tricalcium phosphate combination scaffolds can enhance bone regeneration by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016. 7(1):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scimeca JC, Verron E. The multiple therapeutic applications of miRNAs for bone regenerative medicine. Drug Discov Today 2017. 22(7):1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fang S, Deng Y, Gu P, Fan X. MicroRNAs regulate bone development and regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2015. 16(4):8227–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakasa T, Yoshizuka M, Usman MA, Mahmoud EE, Ochi M. MicroRNAs and Bone Regeneration. Current Genomics, 2015, 16:441–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nugent M MicroRNAs and Fracture Healing. Calcif Tissue Int 2017. 101(4):355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dhungel B, Ramlogan-Steel CA, Steel JC. MicroRNA-Regulated Gene Delivery Systems for Research and Therapeutic Purposes. Molecules 2018. 23(7). pii: E1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Labatut AE, Mattheolabakis G. Non-viral based miR delivery and recent developments. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2018. 128:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peng B, Chen Y, Leong KW. MicroRNA delivery for regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2015. 88:108–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liang D, Luu YK, Kim K, Hsiao BS, Hadjiargyrou M, Chu B. In vitro non-viral gene delivery with nanofibrous scaffolds. Nucleic Acids Res 2005. 33(19):e170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu P, Chen H, Jin R, Weng T, Ho JK, You C, Zhang L, Wang X, Han C. Non-viral gene delivery systems for tissue repair and regeneration. J Transl Med 2018. 16(1):29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chakraborty C, Sharma AR, Sharma G, Doss CGP, Lee SS. Therapeutic miRNA and siRNA: Moving from Bench to Clinic as Next Generation Medicine. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017. 8:132–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mulholland EJ, Dunne N, McCarthy HO. MicroRNA as Therapeutic Targets for Chronic Wound Healing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2017. 8:46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garnero P The Utility of Biomarkers in Osteoporosis Management. Mol Diagn Ther 2017. 21(4):401–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Malemud CJ. MicroRNAs and Osteoarthritis. Cells 2018. 7(8). pii: E92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seeliger C, Balmayor ER, van Griensven M. miRNAs Related to Skeletal Diseases. Stem Cells Dev 2016. 25(17):1261–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]