Abstract

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging infectious zoonosis caused by the SFTS virus. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a life-threatening syndrome associated with excessive immune activation. Cytokine storms are often seen in both SFTS and HLH, resulting in rapid disease progression and poor prognosis. The aim of this study was to identify whether SFTS cases complicated by HLH are related to higher rates of mortality. Descriptive analysis of the frequency of clinical and laboratory data, complications, treatment outcomes, and HLH-2004 criteria was performed. Cases presenting with five or more clinical or laboratory findings corresponding to the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria were defined as SFTS cases complicated by HLH. Eighteen cases of SFTS were identified during a 2-year study period, with a case-fatality proportion of 22.2% (4 among 18 cases, 95% confidence interval 9%–45.2%). SFTS cases complicated by HLH were identified in 33.3% (6 among 18 cases). A mortality rate of 75% (3 among 4 cases) was recorded among SFTS cases complicated by HLH. Although there were no statistically significant differences in outcomes, fatal cases exhibited more frequent correlation with HLH-2004 criteria than non-fatal cases [3/14 (21.4%) vs. 3/4 (75%), p=0.083]. In conclusion, the present study suggests the possibility that SFTS cases complicated by HLH are at higher risk of poor prognosis.

Keywords: SFTS, HLH, mortality

Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is an emerging infectious zoonosis caused by the SFTS virus (SFTSV), a newly identified Phlebovirus in the family Phenuiviridae carried by Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks.1 It is an endemic disease in China, South Korea, and Japan,2 with a case fatality rate of 16.2% to 30%.3,4 Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an immune-mediated life-threatening syndrome associated with excessive immune activation.5 Hyperferritinemia has been identified as a surrogate marker for both HLH and SFTS.6 The major source of high ferritin in HLH has been suggested as a result of activated macrophages in the bone marrow or spleen.7 Cytokine storms in SFTS cause disease progression resulting in a more severe form of clinical severity.8 For this reason, the association of HLH features in SFTS patients has been suggested as a critical factor attributable to increased risk of mortality.9 Fatal cases of SFTS associated with HLH have been described by previous studies,4,5,9 although most are brief reports of one or two cases. The aim of this study was to demonstrate the clinical features and outcomes of SFTS patients complicated by HLH and to compare the frequency of HLH-criteria factors according to outcomes.

This was a retrospective cohort study based on patients treated for SFTS at a tertiary health care hospital in Wonju, South Korea from October 2015 to August 2017. Blood samples obtained from patients during the acute phase of illness were referred to the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for confirmation of SFTSV infection. Using a viral RNA extraction kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, Seongnam, Korea), RNA was extracted from the serum of the patients. For detection of SFTSV RNA, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed using a DiaStar 2X OneStep RT-PCR Pre-Mix kit (SolGent, Daejeon, Korea) under the following conditions according to the manufacturer's instructions: an initial step of 30 min at 50℃ for RT and 5 min at 95℃ for denaturation; 35 cycles of 20 s at 95℃, 40 s at 58℃, and 30 s at 72℃; and a final extension step of 5 min at 72℃. Primers MF3 (5′-GATGAGATGGTCCATGCTGATTCT-3′) and MR2 (5′-CTCATGGGGTGGAATGTCCTCAC-3′) were used.10

Cases presenting with five or more clinical or laboratory findings corresponding to the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria were defined as SFTS cases complicated by HLH.11 The criteria used in the HLH-2004 trial are as follows: fever ≥38.5℃, splenomegaly, peripheral blood cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia (fasting triglycerides >265 mg/dL) and/or hypofibrinogenemia (fibrinogen <150 mg/dL), hemophagocytosis, serum ferritin >500 ng/mL, elevated soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor alpha chain) two SDs above age-adjusted laboratory-specific norms, and low or absent natural killer (NK) cell activity. Cytopenia was defined as at least two affected cell lineages: hemoglobin <9 g/dL (reference 12–16 g/dL), platelets <100000/microL (reference 150000–450000/microL), absolute neutrophil count <1000/microL (reference 1800–7500/microL). Presence of hemophagocytosis was confirmed when identified in bone marrow, spleen, lymph node, or liver.11 Cardiovascular disease was defined in patients with established coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral arterial disease.12 Diabetes was defined as documentation of two consecutive fasting blood glucose measurements ≥7 mmol/L or HbA1c ≥6.5%. Liver disease was defined in patients with chronic liver disease due to viral or alcoholic cause. Renal disease was defined in patients with chronic kidney disease according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes guidelines.13

Analysis of the frequency of each criterion was conducted. Case-fatality proportions for each criterion were compared. Descriptive statistic procedures were performed to analyze the cases. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Continuous variables are presented as a median, interquartile range. Dichotomous variables were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were analysed using the Mann Whitney U-test. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Wonju Severance Christian Hospital (approval No. CR318141). Informed consent was waived by the board.

During the study period, 18 patients were confirmed and treated for SFTS. The clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 18 patients at the time of admission are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the 18 SFTS Confirmed Cases.

| Characteristics | Total (n=18) | Survival (n=14) | Mortality (n=4) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male | 9 (50.0) | 8 (57.1) | 1 (25.0) | 0.576* |

| Age, median year (IQR) | 74 (66, 77) | 72 (66, 77) | 76 (62, 83) | 0.534† |

| Hospital days (IQR) | 12 (6, 17) | 12 (6, 18) | 10 (5, 15) | 0.464† |

| Confirmed insect bite | 12 (66.7) | 10 (71.4) | 2 (50.0) | 0.569* |

| Underlying comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (22.2) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (25.0) | 1.000* |

| Cardiovascular | 7 (38.9) | 4 (28.6) | 3 (75.0) | 0.245* |

| Liver disease | 2 (11.1) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (25.0) | 0.405* |

| Renal disease | 1 (5.6) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000* |

| Solid organ cancer | 2 (11.1) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000* |

| Complication | ||||

| Meningoencephalitis | 4 (22.2) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (25.0) | 1.000* |

| Ventilator care | 3 (16.7) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (50.0) | 0.108* |

| Arrhythmia | 1 (5.6) | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 1.000* |

| Bleeding | 1 (5.6) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (25.0) | 0.222* |

| Hemodialysis | 2 (11.1) | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000* |

| Treatment | ||||

| Plasmapheresis | 6 (33.3) | 4 (28.6) | 2 (50.0) | 0.569* |

| Ribavirin | 8 (44.4) | 6 (42.9) | 2 (50.0) | 1.000* |

| Interferon | 4 (22.2) | 2 (14.3) | 2 (50.0) | 0.197* |

| IVIG | 3 (16.7) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (25.0) | 1.000* |

| Cyclosporine | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.222* |

| Etoposide (VP-16) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.222* |

| Available laboratory test results | ||||

| CBC | 18 (100) | 14 (100) | 4 (100) | |

| Triglyceride | 18 (100) | 14 (100) | 4 (100) | |

| Ferritin | 16 (88.9) | 12 (85.7) | 4 (100) | 1.000* |

| Bone marrow examination | 9 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (100) | 0.082* |

| The HLH-2004 criteria | ||||

| Fever | 18 (100) | 14 (100) | 4 (100) | |

| Splenomegaly | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Hemophagocytosis | 9 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (100) | 0.082* |

| Cytopenia | 16 (88.9) | 12 (85.7) | 4 (100) | 1.000* |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 12 (66.7) | 9 (64.3) | 3 (75.0) | 1.000* |

| Hyperferritinemia | 14 (87.5) | 10 (83.3) | 4 (100) | 1.000* |

| No. cases with five or more factors corresponding to 2004-HLH criteria | 6 (33.3) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (75.0) | 0.083* |

IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; SFTS, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome; CBC, complete blood count; IQR, interquartile range.

The data were expressed as the number of patients (%) or median (IQR).

*Fisher's exact test was performed, †Mann-Whitney U-test was performed.

Nine (50%) of the patients were male, with a median age of 74 years. Males had higher non-fatality proportions of 57.1% (8/14). The presence of a tick bite wound on physical examination was confirmed in 12 (66.7%) patients. Meningoencephalitis with altered mental status as the initial presenting symptom was seen in 4 (22.2%) patients. Ventilator care was required in 3 (16.7%) patients, and 1 (5.6%) patient experienced a tachyarrhythmia event and bleeding during hospitalization. Two (11.1%) patients suffered with acute renal failure requiring hemodialysis. For treatment, 6 (33.3%) patients received plasma exchange for three days. Ribavirin, interferon, and intravenous immunoglobulin was administered in 8 (44.4%), 4 (22.2%), and 3 (16.7%) patients, respectively. Cyclosporine and etoposide (VP-16) was administered in 1 (5.6%) patient each.

In this study, a case-fatality proportion of 22.2% [4 among 18 cases, 95% confidence interval (CI) 9%–45.2%] was recorded. SFTS cases complicated by HLH were identified in 33.3% (6 among 18 cases, 95% CI 16.3%–56.3%). The frequencies of hemophagocytosis [5/14 (35.7%) vs. 4/4 (100%), p=0.082], cytopenia [12/14 (85.7%) vs. 4/4 (100%), p=1.000], hypertriglyceridemia [9/14 (64.3%) vs. 4/4 (100%), p=1.000], and hyperferritinemia [10/14 (83.3%) vs. 4/4 (100%), p=1.000] did not differ significantly between fatal and non-fatal cases. A mortality rate of 75% (3 among 4 cases) was recorded among SFTS cases complicated by HLH. Although there was no statistically significant differences in outcomes, fatal cases demonstrated more frequent correlation to the HLH-2004 criteria, compared to non-fatal cases [3/14 (21.4%) vs. 3/4 (75.0%), p=0.083].

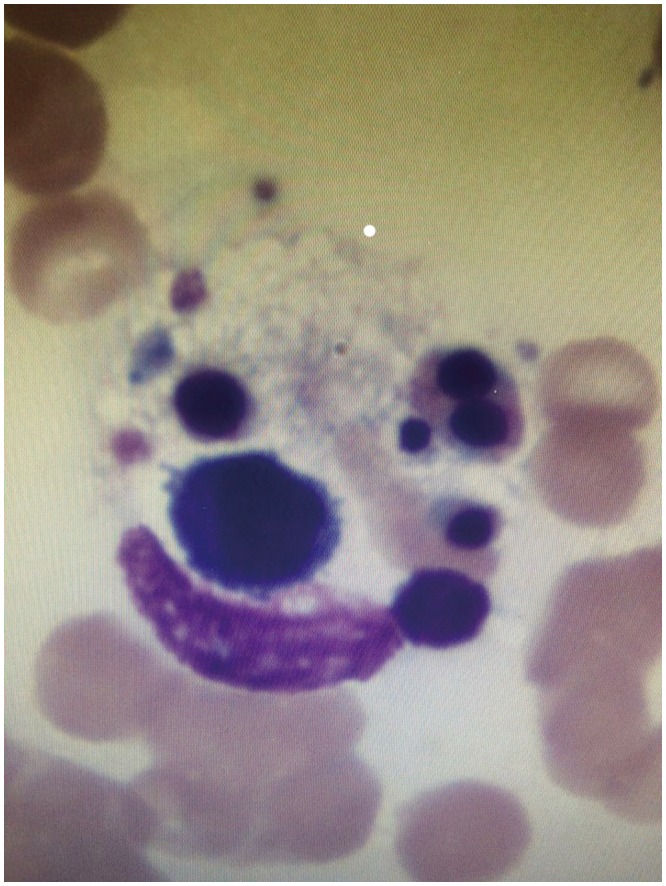

Table 2 lists the clinical characteristics, laboratory data, and outcomes of the six cases with five or more factors corresponding to the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria. With the exception of case number 2, all cases were identified with thrombocytopenia on initial laboratory results. Leukopenia, hyperferritinemia, and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow (Fig. 1) were identified in all six cases. One fatal case was complicated by meningoencephalitis. Despite aggressive ventilator care, plasmapheresis and ribavirin administration, case number 5 resulted in death. Case number 4 survived after receiving plasmapheresis and ribavirin, and case number 6 who also survived was treated with plasmapheresis only.

Table 2. Clinical, Laboratory Data and Outcomes of the Six SFTS Cases Complicated by HLH.

| Case number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 59 | 85 | 57 | 71 | 78 | 76 |

| Gender | F | F | M | F | F | F |

| Symptom onset (day) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Hospital days | 5 | 16 | 11 | 24 | 15 | 17 |

| Laboratory data on day 1 | ||||||

| WBC (×109/L) | 1390 | 2200 | 1050 | 650 | 2200 | 2710 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 12.3 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 11.1 | 13 | 10.4 |

| Platelet (×109/L) | 71 | 138 | 66 | 34 | 35 | 38 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 1346 | 867.9 | >1650 | >1650 | >1650 | >1650 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 363 | 121 | 327 | 155 | 195 | 653 |

| Hemophagocytosis in BM | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Splenomegaly | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Complications | ||||||

| Meningoencephalitis | N | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Ventilator | Y | N | N | N | Y | N |

| Treatment | ||||||

| Plasmapheresis | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Ribavirin | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Outcome | Death | Death | Survival | Survival | Death | Survival |

SFTS, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome; HLH, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; M, male; F, female; Y, yes; N, no; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; BM, bone marrow.

Fig. 1. Presence of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow of case 1 (×1000).

SFTS is an endemic disease in rural South Korea, with a reported incidence of 0.54 cases/10000 person-years from 2013 to 2015 in the Gangwon area of South Korea.14 Although one multicenter study conducted in South Korea suggested that early plasma exchange may have a beneficial effect on the clinical outcomes of SFTS patients,15 there are no specific established treatments for SFTS.

Recent results from the Chinese national surveillance system reported a case-fatality rate of 16.2% (95% CI 14.6–17.8).3 The case-fatality rate was 22.2% in our study, higher than reports from China. This discrepancy may be attributable to the underestimation of deaths of patients who had stopped therapy, been discharged from the hospital, and died soon after returning home. Moreover, older median age and a higher frequency of comorbid underlying diseases may explain the higher rates of case-fatality reported in this study.

Secondary HLH has been shown to be associated with SFTS with hyperferritinemia and evidence of hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow.16,17 In one study conducted in Japan, hemophagocytosis in bone marrow was identified in 83% of cases, with a case-fatality proportion of 31%.16 In this study, hemophagocytosis was identified in all four fatal cases. However, there were no statistically significant differences between fatal and non-fatal cases according to the presence of hemophagocytosis.

There are several limitations to our study. First, the study was limited by its retrospective nature and its small sample size. This was a single-center study, and although the center in which the study was conducted was located in a rural area of South Korea with a relatively high incidence of SFTS, only a limited number of cases were identifiable. Second, NK cell activity or soluble CD25 concentrations were not identifiable due to limitation of laboratory resources. Moreover, serum ferritin and bone marrow examination was not performed for all cases. This may have caused an underestimation in diagnosis of HLH complicated cases.

Although there were no statistically significant differences in outcomes between HLH complicated cases and HLH non-complicated cases, 75% mortality was identified in SFTS cases complicated by HLH. Although further studies with a larger number of patients are needed to support this finding, the present study suggests the possibility that SFTS cases complicated by HLH are at higher risk of poor prognosis.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Young Keun Kim.

- Data curation: In Young Jung.

- Formal analysis: In Young Jung.

- Funding acquisition: Not applicable.

- Investigation: In Young Jung.

- Methodology: In Young Jung.

- Project administration: In Young Jung.

- Resources: Not applicable.

- Software: Not applicable.

- Supervision: Young Keun Kim.

- Validation: In Young Jung and Young Keun Kim.

- Visualization: In Young Jung and Young Keun Kim.

- Writing—original draft: In Young Jung.

- Writing—review & editing: Kwangjin Ahn, Juwon Kim, Jun Yong Choi, Hyo Youl Kim, Young Uh, Young Keun Kim.

References

- 1.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) Taxonomy. [accessed on 2017 May 3]. Available at: https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy.

- 2.Liu Q, He B, Huang SY, Wei F, Zhu XQ. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:763–772. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70718-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Lu QB, Xing B, Zhang SF, Liu K, Du J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of laboratory-diagnosed severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in China, 2011-17: a prospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18:1127–1137. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaneko M, Azuma T, Yasukawa M, Shinomiya H. A fatal case of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome complicated by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Kansenshogaku zasshi. 2015;89:592–596. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi.89.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh HS, Kim M, Lee JO, Kim H, Kim ES, Park KU, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with SFTS virus infection: a case report with literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4476. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim UJ, Oh TH, Kim B, Kim SE, Kang SJ, Park KH, et al. Hyperferritinemia as a diagnostic marker for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Dis Markers. 2017;2017:6727184. doi: 10.1155/2017/6727184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen LA, Gutierrez L, Weiss A, Leichtmann-Bardoogo Y, Zhang DL, Crooks DR, et al. Serum ferritin is derived primarily from macrophages through a nonclassical secretory pathway. Blood. 2010;116:1574–1584. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-253815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gai ZT, Zhang Y, Liang MF, Jin C, Zhang S, Zhu CB, et al. Clinical progress and risk factors for death in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome patients. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1095–1102. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakano A, Ogawa H, Nakanishi Y, Fujita H, Mahara F, Shiogama K, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a fatal case of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Intern Med. 2017;56:1597–1602. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.56.6904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim N, Kim KH, Lee SJ, Park SH, Kim IS, Lee EY, et al. Bone marrow findings in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome: prominent haemophagocytosis and its implication in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:537–541. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, Filipovich AH, McClain KL. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118:4041–4052. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-278127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, et al. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Kidney Int. 2005;67:2089–2100. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi SJ, Park SW, Bae IG, Kim SH, Ryu SY, Kim HA, et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in South Korea, 2013-2015. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0005264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oh WS, Yoo JR, Kwon KT, Kim HI, Lee SJ, Jun JB, et al. Effect of early plasma exchange on survival in patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome: a multicenter study. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58:867–871. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2017.58.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato H, Yamagishi T, Shimada T, Matsui T, Shimojima M, Saijo M, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in Japan, 2013-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0165207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin SY, Cho OH, Bae IG. Bone marrow suppression and hemophagocytic histiocytes are common findings in Korean severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome patients. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:1286–1289. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.5.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]