Abstract

Addition of brentuximab vedotin, a CD30-targeted antibody–drug conjugate, and the programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab to the armamentarium for transplant-ineligible relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma has resulted in improved outcomes, including the potential for cure in a small minority of patients. For patients who have failed prior transplant or are unsuitable for dose-intense approaches based on age or comorbidities, an individualized approach with sequential use of single agents such as brentuximab vedotin, PD-1 inhibitors, everolimus, lenalidomide, or conventional agents such as gemcitabine or vinorelbine may result in prolonged survival with a minimal or modest effect on quality of life. Participation in clinical trials evaluating new approaches such as combination immune checkpoint inhibition, novel antibody–drug conjugates, or cellular therapies such as Epstein-Barr virus–directed cytotoxic T lymphocytes and chimeric antigen receptor T cells offer additional options for eligible patients.

Introduction

More than 80% of patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) will be cured with initial treatment1-4 and among patients who relapse, ∼50% can be cured with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).5-7 However, for those patients who progress after ASCT or are ineligible for an autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant due to refractory disease, age, or organ dysfunction, there are limited treatment options, and long-term remissions are uncommon. Importantly, while patients aged ≥60 years represent only 15% to 20% of newly diagnosed HL cases, they have worse reported outcomes and may be more likely to require subsequent lines of therapy.8,9

Fortunately, with the recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals of brentuximab vedotin (BV) and the programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab, promising new options for transplant-ineligible patients are available.10-12 These 2 novel classes of drugs have relatively favorable toxicity profiles, making them appealing for older patients and those with significant comorbidities. The approach to patients with relapsed HL who are not candidates for dose-intense therapy should be individualized based on response to prior lines of therapy, comorbidities, and the likely side effects of salvage therapy. In general, in an effort to minimize toxicity and accurately assess response, single-agent therapy is often the best approach for this subset of patients and may allow optimization of dose and schedule. This article summarizes standard options and promising new therapies for recurrent HL in older or frail patients or those with multiply relapsed disease.

Case presentation

A 20-year-old woman was diagnosed with stage III HL and treated with 6 cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine followed by radiotherapy to the cervical nodes and mediastinum. Four years later, HL recurred in retroperitoneal nodes, and the patient received 3 cycles of etoposide, solumedrol, cytarabine, and cisplatin followed by an ASCT. Her disease progressed in the abdomen ∼4 years following transplant; she received 5 cycles of gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin in a clinical trial and achieved a response of stable disease. Lenalidomide was administered for 20 months during a phase 2 trial until symptomatic progression occurred. Involved field radiotherapy to the spine and retroperitoneal nodes was followed by single-agent everolimus therapy for 5 months with an initial partial remission. Biopsy-proven progression in iliac nodes was treated with 16 cycles of BV. This now 38-year-old woman remains in complete remission more than 5 years after treatment with BV and 14 years after failing ASCT.

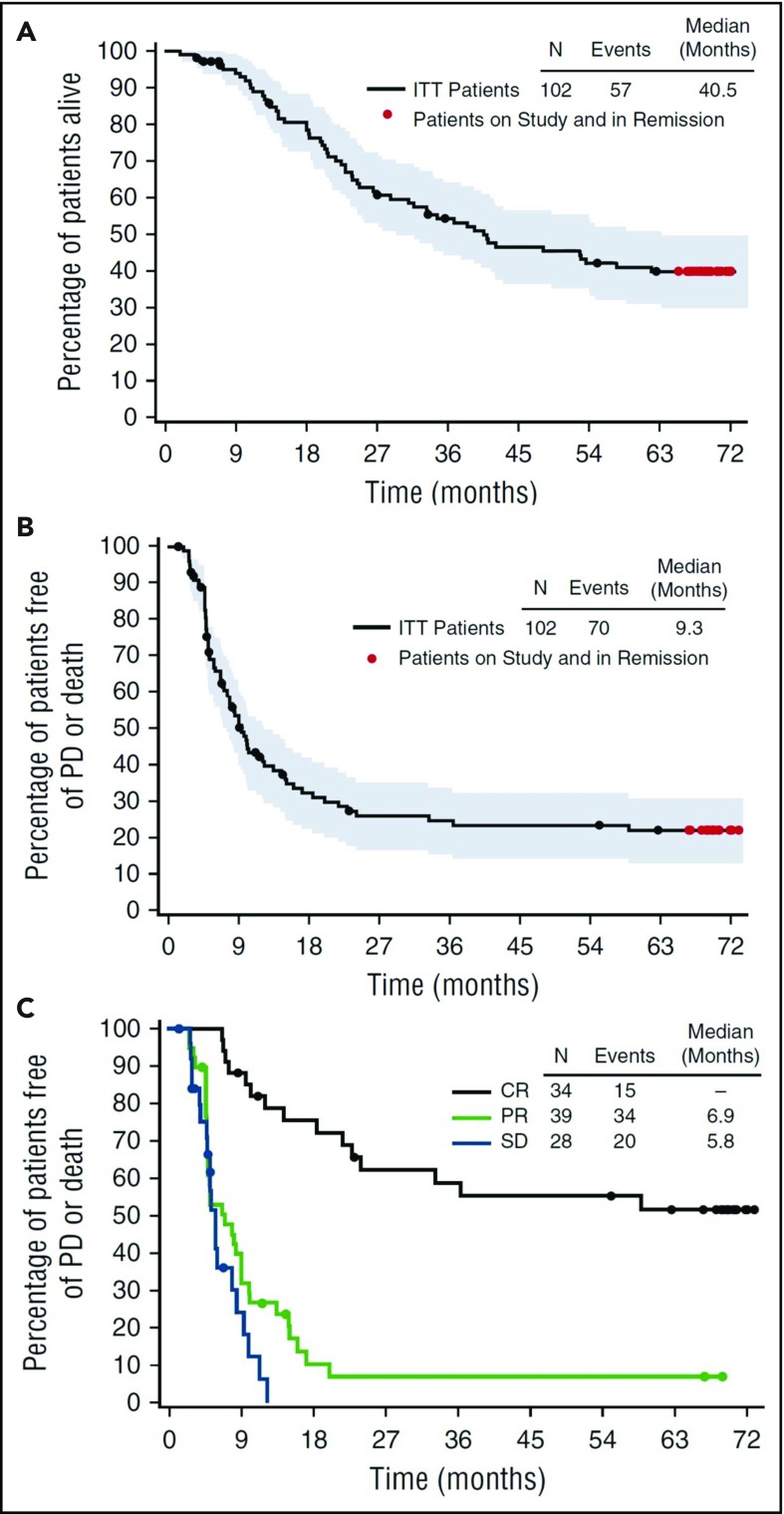

BV

BV, an anti-CD30 antibody conjugated to the microtubule-disrupting agent monomethyl auristatin E, was FDA approved in 2011 for relapsed or refractory HL after an ASCT or following 2 prior lines of therapy. In the pivotal phase 2 trial of BV, 102 patients with relapsed HL received treatment with single-agent BV (1.8 mg/m2 every 3 weeks) after failing an ASCT.10 The overall response rate (ORR) and complete response (CR) rate were 75% and 33%, respectively, with a median response duration of 6.7 months for all responders and 20.5 months for those in CR (Figure 1). At 5 years, the estimated overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates were 41% and 22%.10,13 For the 33% of patients who achieved a CR to BV, the 5-year OS and PFS rates were 64% and 52%.13 At the conclusion of the study, 13 patients remained in CR with a median follow up of 69.5 months. These 13 patients received a median of 14 cycles of BV. While 4 out of 13 patients underwent an allogeneic SCT, 9 out of 13 patients (or 26% of patients achieving CR) remained in remission without any further therapy. Patients who had a sustained CR were more likely to be younger, have more extranodal disease, and have a shorter time from initial diagnosis to treatment with BV.13 These data suggest that a small percentage of patients in the relapsed or refractory setting may be cured with BV. Additionally, for patients who relapse following response to BV, 60% respond to retreatment with BV, including 30% who achieve a CR.14

Figure 1.

Five-year follow-up of patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) Hodgkin lymphoma who failed ASCT, treated with BV. Censored patients are indicated by black dots, patients followed through study closure and in remission without the start of new therapy other than allo-SCT are indicated by red dots. Shown are overall survival (A), overall PFS (B) and PFS by best response (C). Reprinted from Chen et al13 with permission. Copyright 2016 The American Society of Hematology.

Single-agent BV is well tolerated, with the most common reported grade 3 or 4 adverse events being peripheral sensory neuropathy (8%), fatigue (2%), neutropenia (20%), and diarrhea (1%). Neuropathy is the most common reason for discontinuation of therapy for responding patients. As sensory and motor neuropathy can significantly impact quality of life, dose reductions (initially to 1.2 mg/m2 or 0.9 mg/m2) every 3 weeks can help mitigate this toxicity in patients who develop clinically significant neuropathy. Extending the cycle length to 4 to 6 weeks for later cycles may also decrease the severity of neuropathy while maintaining efficacy.15 The administration of 16 cycles (1 year) of therapy in the initial studies was empiric. The median time to response was 5.7 weeks and 12 weeks to CR, which corresponded to the first positron emission tomography restaging.10 For patients in early CR with progressive symptomatic neuropathy or other significant side effects, an abbreviated course of BV (6-8 cycles) with retreatment at relapse may be an alternative approach to prolonged therapy.

There have been attempts to study BV-based combination therapy options both in the upfront and relapsed setting. A study of BV and bendamustine (n = 55) in patients with relapsed HL showed an ORR of 93% with a CR rate of 74% and 1-year PFS of 80%.16 Among those with primary refractory disease, the CR rate was 64%. However, infusion reactions occurred in 56% of patients and included fevers, chills, nausea, flushing, dyspnea, and hypotension, which were significantly higher than seen with either agent alone. Pretreatment with corticosteroids and antihistamines decreased the severity of the reactions. In an older patient population, BV has been studied in combination with bendamustine reduced to 70 mg/m2 (n = 11) or dacarbazine (n = 22) as frontline therapy. Both combinations carried an ORR of 100% with a high rate of CR, but the BV bendamustine arm was stopped after only 11 patients were treated due to the high incidence of grade 3 and 4 events.17 In contrast, the preliminary results of the phase 1/2 HALO study of BV (1.2 mg/m2 day 1) with bendamustine (90 mg/m2 days 1 and 2) every 21 days for 6 cycles in the frontline setting in older patients with HL showed tolerable side effects.18 Despite the high response rates, combinations of BV with cytotoxic chemotherapy are less attractive in transplant-ineligible patients because of common serious side effects and the inability to administer prolonged therapy.

Checkpoint inhibitors

Nivolumab and pembrolizumab, inhibitors of PD-1, were recently FDA approved for relapsed/refractory HL. HL carries a genetic susceptibility to checkpoint inhibitors based on the consistent amplification of chromosome 9p in almost all cases of HL.11,19 Chromosome 9p harbors the genes for PD-1 ligand, PD-L1 and PD-L2, and amplification of the 9p24.1 locus leads to uniform overexpression of PD-L1 ligands in HL. The current approval for nivolumab includes patients who have failed both an ASCT and BV. Pembrolizumab has a slightly broader indication for patients with refractory HL or who have failed at least 3 lines of prior therapy.

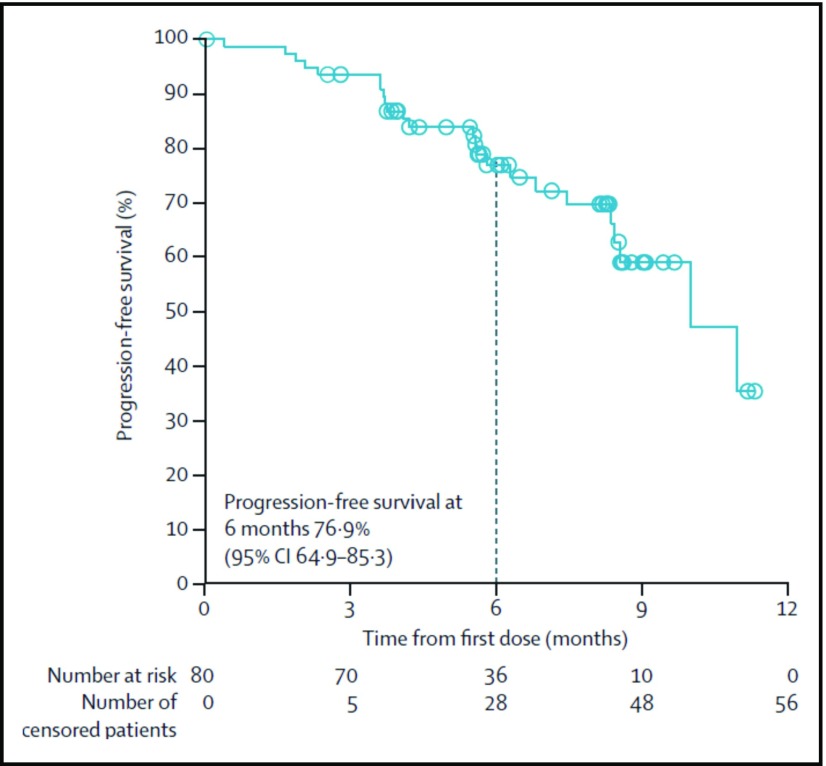

In the pivotal phase 2 study of nivolumab dosed at 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks, 80 patients with relapsed/refractory HL who failed both ASCT and BV had an ORR of 66.3% with 9% CRs.11 The median duration of response was 7.8 months (Figure 2). Responses occurred in two-thirds of patients who had not responded to prior BV. Additionally, in the subset of patients with biopsy specimens available for correlative studies, patients who had the highest density of PD-L1 and PD-L2 (top 2 quartiles) on Reed-Sternberg cells (PD-L1 H score) had higher response rates and more frequent CRs than patients with lower scores.11 All patients with progressive disease were in the lowest quartile of PD-L1 H scores, although responses were even seen in this group.

Figure 2.

Independent radiological review committee (IRRC)-assessed progression-free survival at 6 months of patients treated with nivolumab (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks) who had not responded to ASCT and BV. CI, confidence interval. Reprinted from Younes et al11 with permission.

Pembrolizumab was studied in a multicenter single-arm phase 2 study of 210 patients with relapsed/refractory HL after ASCT or a lack of response to salvage therapy and progression on BV. Pembrolizumab was administered at a flat dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks. The ORR was 66.7% with a median duration of response of 11.1 months. Among patients with primary refractory HL, the ORR and CR rate was 79% and 23%, respectively.12,20

While pembrolizumab and nivolumab are generally well tolerated, patients are at risk for adverse reactions associated with immune activation. In the registration trial of nivolumab, 89% of patients had treatment-related adverse events, including 54% with grade 1 or 2 events. The most common events were fatigue (25%), infusion-related reactions (20%), rash (16%), pyrexia (14%), arthralgias (14%), pruritus (10%), and diarrhea (10%).11 26 patients (33%) had grade 3 events and 6 (4%) had grade 4 events, with the most common being asymptomatic lipase elevation and neutropenia. Only 3 of 80 patients had adverse events leading to discontinuation of treatment (1 patient had autoimmune hepatitis, 1 patient had transaminitis, and 1 patient died of multisystem organ failure deemed to be unrelated to treatment). Pneumonitis was only seen in 2 patients (1 with grade 2 disease and 1 with grade 3 disease) and both resolved with corticosteroid treatment. The most common treatment-related adverse events with pembrolizumab include pyrexia (11.0%), hypothyroidism (10.5%), diarrhea (6.7%), fatigue (6.7%), headache (6.2%), rash (6.2%), and nausea (5.7%).12,20 Grade 3 or 4 toxicities occurred in only 4.4% of patients and included neutropenia, dyspnea, and diarrhea. Nine patients (4.3%) discontinued treatment due to treatment-related adverse events, which included myocarditis, myelitis, myositis, pneumonitis, infusion-related reactions, and cytokine release syndrome. Importantly, there were no deaths attributed to treatment in either study.

Overall, PD-1 inhibitors represent an excellent treatment option for patients including those who have primary refractory HL and are not eligible for an ASCT or have relapsed following transplant. Studies of checkpoint inhibitors in combination with BV are ongoing in first-line therapy of older patients, second-line therapy as pretransplant cytoreduction, and in patients with relapsed/refractory HL. Preliminary results of the E4412 study of BV in combination with nivolumab in 19 patients with relapsed or refractory HL demonstrated an ORR of 89% with 50% of patients achieving a CR.21 Responses were seen in patients previously treated with BV. Two patients developed pneumonitis, 1 of which was fatal. Other arms of this study included treatment with BV in combination with ipilumumab as well as treatment with BV, nivolumab, and ipilumumab (NCT01896999). Similarly, a study of BV with nivolumab as second-line therapy pre-ASCT (n = 62) demonstrated an 85% ORR with 64% CRs.22 Four patients required steroids for immune-related adverse events, including 1 patient with grade 4 pneumonitis and colitis. While combination strategies appear promising, the durability of response and toxicity of these therapies will need to be evaluated in larger studies. It is not currently clear whether combination therapy represents an advantage over sequential single-agent therapy in the transplant-ineligible population.

An ongoing randomized phase 3 trial is comparing pembrolizumab to BV in patients with relapsed or refractory HL who have either failed ASCT, are ineligible for ASCT because of refractory disease after 2 lines of therapy, or are at least 65 years old (NCT02684292). Another ongoing phase 3 study is comparing BV alone to nivolumab plus BV in patients with relapsed/refractory HL or patients not eligible for an ASCT (NCT03138499).

Everolimus

Everolimus, an oral inhibitor of mammalian target of rapamycin, is not FDA approved for the treatment of HL but has significant activity in relapsed/refractory HL and is currently listed as a treatment option for HL in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.23 In a small phase 2 study, 19 patients with relapsed/refractory HL were treated with single-agent everolimus (10 mg daily), with an ORR of 47% and 1 CR.24 This was recapitulated in a larger multicenter study of 57 patients with an ORR of 42%, including 5 CRs and a median PFS of 9 months.25 Seven patients were able to remain on treatment for >3 years. Of note, pneumonitis was seen in 3 patients, and as in other approved indications for everolimus, when treated with immediate initiation of corticosteroids and clinical symptoms and radiographic changes have resolved, patients can be safely rechallenged with 5 mg daily. Single-agent everolimus is well tolerated, can often be continued until disease progression without cumulative toxicity, and represents an excellent treatment option for heavily pretreated HL.

Lenalidomide

Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory agent now believed to exert its action by interacting with ubiquitin E3 ligase cereblon and degrading Ikaros transcription factors in lymphoid malignancies.26 There have been two studies of lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory HL. A small phase 2 study of 15 patients treated with lenalidomide demonstrated 2 PRs.27 In a larger phase 2 study of single-agent lenalidomide (25 mg daily for 21 of 28 days) in 36 patients with relapsed/refractory HL, the ORR was 19.4%, but an additional 13.9% had stable disease for more than 6 months. In a second cohort of 37 patients treated with continuous dosing at 25 mg daily, the ORR was 29%.28 Therapy was well tolerated even in a population that had previously undergone ASCT.29 Continuous dosing was associated with a modest increase in hematological toxicity. Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia were seen in 46%, 26%, and 12% of patients, respectively, and 4 patients required discontinuation of therapy because of cytopenias. Although not FDA approved for HL, single-agent lenalidomide is listed as a treatment option for refractory HL in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.23 Studies of lenalidomide combined with histone deacetylase inhibitors in HL have not yielded improved responses and were associated with significant toxicity.30

Conventional chemotherapy

Although BV, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab have greatly impacted the treatment of HL and represent excellent options for transplant-ineligible HL, most patients will eventually relapse. If there are no clinical trial options available for patients with relapsed/refractory HL, then retreatment with conventional chemotherapy agents should be considered in this setting. While combination chemotherapy regimens used in the salvage setting often have cumulative dose-limiting toxicity and may be difficult to tolerate for older patients, single-agent therapy is an option. Single-agent bendamustine showed a response rate of 53% to 58% with 25% to 33% being CRs in phase 2 studies.31,32 However, the median duration of response was 5 months. Single-agent gemcitabine and vinorelbine have been studied in heavily pretreated HL with ORRs of 39% and 50%, respectively, and median durations of response of ∼6 months.33,34 The combination of gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin has been studied in relapsed/refractory HL through the Cancer and Leukemia Group B with an ORR of 70% with 19% CRs.35 In patients who had previously undergone an ASCT, the median event-free survival was 8.5 months. Lomustine (CCNU), an oral alkylating agent, was studied in relapsed/refractory HL in the 1980s and had a single-agent response rate as high as 60% with a median duration of response of 4.5 months.36 We have observed occasional patients with responses to CCNU lasting >2 years despite progression on other alkylating agents. The recommended CCNU dose is 130 mg/m2 every 6 to 8 weeks as tolerated, with thrombocytopenia being the most common side effect. Similarly, single-agent vinblastine (4-6 mg/m2 every 1-2 weeks until progression or intolerance) had an ORR of 59% with 2 CRs in 17 patients with relapsed HL following an ASCT.37 The median event-free survival was 8.3 months, with the 2 patients in CR remaining in remission for 4.6+ and 9+ years. Importantly, these studies were reported in the pre-BV era, and the benefit of tubulin inhibitors such as vinblastine and vinorelbine in patients who fail BV is unknown, although response rates are likely significantly lower than reported in previous studies.

Cellular therapy in HL

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy has shown encouraging results in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Therefore, CAR T-cell therapy is being explored in HL as well. There have been 2 studies of CAR T-cells published in HL. Eighteen patients with relapsed/refractory HL were treated in a phase 1 trial of CD30-specific CAR T-cells, with 7 patients (39%) achieving partial remission with a median PFS of 6 months.38 Other trials for CD30-directed CAR T-cells are currently underway (NCT01316146, NCT02690545, and NCT02917083). Others have studied autologous Epstein-Barr virus–directed cytotoxic T lymphocytes in Epstein-Barr virus–expressing lymphomas (including HL) and demonstrated that 13 of 21 patients who had measurable disease at the time of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte infusion had responses, including 11 CRs.39 Other possible targets of cellular therapy include CD123, which is expressed in 50% of Reed-Sternberg cells.40 While there may be patients who have relapsed following an ASCT who would be candidates for cellular therapy in HL, patients who are ineligible for transplant because of medical comorbidities may also be ineligible for cellular therapy approaches due to the potential for life-threatening toxicities such as cytokine release syndrome.

Other novel therapies in HL

A number of other potential therapies are being explored for relapsed/refractory HL and remain in phase 1 studies. AFM13 is a tetravalent bispecific chimeric recombinant antibody targeting CD30 and CD16A and is being studied in combination with pembrolizumab. The single-agent response rate to AFM13 was 11.5%, but preclinical data support the use of this combination strategy.41 Preliminary results of an early phase 1 study of a pyrrolobenzodiazepine-based antibody-drug conjugate targeting CD25 included 4 patients with HL with 14 responses (ORR of 63.6%) and 6 (27.3%) CRs at a dose ≥30 μg/kg (NCT02432235).42 Ibrutinib, an inhibitor of Bruton tyrosine kinase, is being studied as a single agent (NCT02824029) and in combination with nivolumab (NCT02940301) and BV (NCT02744612). Nivolumab is also being studied in combination with other forms of immune checkpoint inhibition, such as anti-Lag (NCT02061761).

Conclusions

Historically, the outlook for patients with transplant-ineligible relapsed HL has been poor, with median overall survival of 1 or 2 years for patients relapsing after ASCT. Encouragingly, new agents such as BV and PD-1 inhibitors appear to be improving outcomes for these patients, with a median OS of 40.5 months and a 5-year survival of 41% for patients enrolled on the phase 2 trial of single-agent BV after failing ASCT.13 Patients with relapsed/refractory HL who are not eligible for transplant often continue to have an excellent performance status despite active disease and should be considered for clinical trials. Single-agent BV, PD-1 inhibitors, everolimus, lenalidomide, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and CCNU are all potential standard-of-care options. Patients can often tolerate multiple sequential agents, and if there has been a long interval to relapse after a previous response, then retreatment with the same agent may be effective. The cumulative toxicities and tolerance should drive the length of treatment in responding patients. Additional promising novel approaches are in clinical trial and the outlook for patients with multiple relapses of HL is hopeful.

Authorship

Contribution: N.M.-S. and N.L.B. reviewed the literature and wrote the review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.L.B. has participated in advisory boards for Pfizer, KITE, and Seattle Genetics and has received institutional research funding from Affimed, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dynavax, Forty Seven, Genentech, Gilead, Idera, Immune Design, Incyte, Janssen, KITE, MedImmune, Merck & Co, Takeda, Novartis, Pfizer, Pharmacyclics. and Seattle Genetics. N.M.-S. has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, and Verastem.

Correspondence: Nancy Bartlett, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, Siteman Cancer Center, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 South Euclid Ave, Box 8056, St. Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: nbartlet@wustl.edu.

References

- 1.Press OW, Li H, Schöder H, et al. US Intergroup Trial of response-adapted therapy for stage III to IV Hodgkin lymphoma using early interim fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography imaging: Southwest Oncology Group S0816. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(17):2020-2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, et al. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET-CT scan in advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(25):2419-2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radford J, Illidge T, Counsell N, et al. Results of a trial of PET-directed therapy for early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(17):1598-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engert A, Haverkamp H, Kobe C, et al. ; Arbeitsgemeinschaft Medikamentöse Tumortherapie. Reduced-intensity chemotherapy and PET-guided radiotherapy in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HD15 trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9828):1791-1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morschhauser F, Brice P, Fermé C, et al. ; GELA/SFGM Study Group. Risk-adapted salvage treatment with single or tandem autologous stem-cell transplantation for first relapse/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma: results of the prospective multicenter H96 trial by the GELA/SFGM study group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(36):5980-5987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, et al. ; Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin’s disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9323):2065-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linch DC, Winfield D, Goldstone AH, et al. Dose intensification with autologous bone-marrow transplantation in relapsed and resistant Hodgkin’s disease: results of a BNLI randomised trial. Lancet. 1993;341(8852):1051-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evens AM, Helenowski I, Ramsdale E, et al. A retrospective multicenter analysis of elderly Hodgkin lymphoma: outcomes and prognostic factors in the modern era. Blood. 2012;119(3):692-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Ongoing improvement in long-term survival of patients with Hodgkin disease at all ages and recent catch-up of older patients. Blood. 2008;111(6):2977-2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(18):2183-2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Younes A, Santoro A, Shipp M, et al. Nivolumab for classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma after failure of both autologous stem-cell transplantation and brentuximab vedotin: a multicentre, multicohort, single-arm phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1283-1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen R, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA, et al. ; KEYNOTE-087. Phase II study of the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory classic hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2125-2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen R, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Five-year survival and durability results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2016;128(12):1562-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartlett NL, Chen R, Fanale MA, et al. Retreatment with brentuximab vedotin in patients with CD30-positive hematologic malignancies. J Hematol Oncol. 2014;7(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foyil KV, Kennedy DA, Grove LE, Bartlett NL, Cashen AF. Extended retreatment with brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) maintains complete remission in patient with recurrent systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(3):506-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaCasce AS, Bociek G, Sawas A, et al. Brentuximab vedotin plus bendamustine: a highly active salvage treatment regimen for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma [abstract]. Blood. 2015;126(23). Abstract 3982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasenchak CA, Forero-Torres A, Cline-Burkhardt VJM, et al. Brentuximab vedotin in combination with dacarbazine or bendamustine for frontline treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma in patients aged 60 years and above: interim results of a multi-cohort phase 2 study [abstract]. Blood. 2015;126(23). Abstract 587. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallamini A, Rambaldi A, Bijou F, et al. A phase 1/2 clinical trial of brentuximab-vedotin and bendamustin in elderly patients with previously untreated advanced Hodgkin lymphoma (HALO study. NCT identifier: 02467946): Preliminary Report [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128(22). Abstract 4154. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green MR, Monti S, Rodig SJ, et al. Integrative analysis reveals selective 9p24.1 amplification, increased PD-1 ligand expression, and further induction via JAK2 in nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116(17):3268-3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moskowitz CH, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA, et al. Pembrolizumab in relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma: primary end point analysis of the phase 2 Keynote-087 study [abstract]. Blood. 2016;128(22). Abstract 4085. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diefenbach CS, Hong F, David K, et al. Safety and efficacy of combination of brentuximab vedotin and nivolumab in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: a trial fo the ECOG-ACRIN cancer research group (E4412). Hematol Oncol. 2017;35:84-85.28591425 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herrera AF, Moskowitz AJ, Bartlett NL, et al. Interim results from a phase 1/2 study of brentuximab vedotin in combination with nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2017;35:85-86. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoppe RT, Advani R, Ai W, et al. Hodgkin Lymphoma Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15(5):608-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston PB, Inwards DJ, Colgan JP, et al. A phase II trial of the oral mTOR inhibitor everolimus in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(5):320-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston PB, Pinter-Brown L, Rogerio J, Warsi G, Chau Q, Ramchandren R. Everolimus for relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma: multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study [abstract]. Blood. 2012;120(21). Abstract 2740. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kritharis A, Coyle M, Sharma J, Evens AM. Lenalidomide in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: biological perspectives and therapeutic opportunities. Blood. 2015;125(16):2471-2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuruvilla J, Taylor D, Wang L, et al. Trial of lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2008;112(11):1049-1049. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fehniger TA, Larson S, Trinkaus K, et al. A phase 2 multicenter study of continuous dose lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma [abstract]. Blood. 2012;120(21). Abstract 1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fehniger TA, Larson S, Trinkaus K, et al. A phase 2 multicenter study of lenalidomide in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118(19):5119-5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maly JJ, Christian BA, Zhu X, et al. A phase I/II trial of panobinostat in combination with lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17(6):347-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moskowitz AJ, Hamlin PA Jr, Perales MA, et al. Phase II study of bendamustine in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(4):456-460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El Cheikh J, Massoud R, Haffar B, et al. Bendamustine as a bridge to allogeneic transplant in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma patients who failed salvage brentuximab vedotin postautologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(11):2745-2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devizzi L, Santoro A, Bonfante V, et al. Vinorelbine: an active drug for the management of patients with heavily pretreated Hodgkin’s disease. Ann Oncol. 1994;5(9):817-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Santoro A, Bredenfeld H, Devizzi L, et al. Gemcitabine in the treatment of refractory Hodgkin’s disease: results of a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(13):2615-2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bartlett NL, Niedzwiecki D, Johnson JL, et al. ; Cancer Leukemia Group B. Gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (GVD), a salvage regimen in relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma: CALGB 59804. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(6):1071-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen HH, Selawry OS, Pajak TF, et al. The superiority of CCNU in the treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s disease: Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. Cancer. 1981;47(1):14-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Little R, Wittes RE, Longo DL, Wilson WH. Vinblastine for recurrent Hodgkin’s disease following autologous bone marrow transplant. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):584-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang CM, Wu ZQ, Wang Y, et al. Autologous T cells expressing CD30 chimeric antigen receptors for relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: an open-label phase I trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(5):1156-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bollard CM, Gottschalk S, Torrano V, et al. Sustained complete responses in patients with lymphoma receiving autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(8):798-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruella M, Kenderian SS, Shestova O, et al. Novel chimeric antigen receptor T cells for the treatment of Hodgkin lymphoma [abstract]. Blood. 2014;124(21). Abstract 806. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothe A, Sasse S, Topp MS, et al. A phase 1 study of the bispecific anti-CD30/CD16A antibody construct AFM13 in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2015;125(26):4024-4031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horwitz SM, Hamadani N, Fanale MA, et al. Interim results from a phase 1 study of ADCT-301 (camidanlumab tesirine) show promising activity of a novel pyrrolobenzodiazepine-based antibody drug conjugate in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin/non-Hodgkin lymphoma [abstract]. Blood. 2017;130(suppl 1). Abstract 1510 [Google Scholar]