Abstract

Background

This study investigated the effectiveness of an integrative medicine program (IMP) for dementia prevention on cognitive function, depression and quality of life (QOL) of elderly in a public health center.

Methods

This study employed a before-after study design to assess effectiveness of the IMP for dementia prevention for community dwelling elderly over 60 without diagnosis of dementia. Cognitive function was measured using the Mini Mental State Examination for Dementia screening (MMSE-DS), digit span test (DST) and trail making test (TMT). The Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form- Korean version (GDSSF-K) and EQ-5D were used to evaluate depression and health-related quality of life. The IMP composed of acupuncture, moxibustion, physical activities, meditation, laughter therapy and music therapy was held once a week over 8 weeks. A paired t-test was used to compare the pre and post-test results.

Results

After screening 93 people, a total of 48 were included in the analysis. Evaluation of the cognitive function revealed that TMT-A (p = 0.028) and TMT-B (p = 0.0013) were significantly reduced, but MMSE-DS (p = 0.309) and DST (DSF: p = 0.855, DSB: p = 0.176) were not statistically significant. Depression (p < 0.01) and preventive behavior for dementia (p < 0.0001) of the participants were improved after the IMP.

Conclusion

The IMP for dementia prevention may have beneficial effects on cognitive function and depression of elderly. However, a well-designed follow-up study is needed to confirm this conclusion.

Keywords: Integrative medicine program, Cognitive function, Public health center, Korean medicine, Health promotion program

1. Introduction

Dementia is a significant problem in elderly individuals that also influences public health. There were an estimated 50 million people with dementia worldwide in 2018 and 9.9 million new cases occur every year. In addition, medical expenditures for dementia in 2018 were estimated to be US$ 1 trillion, which is expected to double by 2030.1

Despite many attempts to develop an effective cure for dementia, these have not been successful and the paradigm has changed to focus on prevention of the disease.1, 2 Pathological progress begins before clinical signs appear; therefore, it is important to prevent and intervene in healthy and preclinical stages. Recent studies have used multimodal approaches including exercise, depression, and managing risk factors of dementia that can be modifiable.3 However, dementia programs in Republic of Korea usually focus on dementia patients and caregivers, while there are few preventive programs for healthy and high risk elderly.4

Traditional medicine in East Asian countries such as Korea, China, and Japan emphasizes preventing diseases, which is known as ‘mibyung (未病)’. Mibyung is a concept that refers to sub-health, including healthy state, incubation period of a disease and having symptoms, but below the diagnosis criteria.5 In mibyung, there are many integrative medicine programs (IMPs) for disease prevention and health promotion targeting individuals from children to elderly in community health centers. IMPs for dementia prevention have been conducted at some public health centers, but few of these have been academically reported.6, 7 IMPs for dementia prevention are composed of acupuncture, exercise and various activities to stimulate cognitive function, to improve quality of life (QOL) and relieve depression. In the previous studies, acupuncture may have positive effects on cognition, demonstrating better cognition scores than drugs alone and improved effects of drugs during amnestic mild cognitive impairment.8 Moxibustion has been suggested to improve memory and daily living activities while reducing frequent urination and dyspepsia.9 It has been shown to be beneficial in irritable bowel syndrome and more effective at treating primary insomnia than medication.10, 11 Physical activity is recommended for dementia prevention with moderate strength of evidence.3 Meditation may offset age-related cognitive declines,12 while music, laughter and herbal tea therapy reduce depression and stress.13, 14, 15

In this study, we investigated the effectiveness of the IMP for dementia prevention for community-dwelling elderly in a public center. We primarily focused on the cognitive effects of the program, using measures for global cognition, attention and executive function. Also, effects on depression, QOL and dementia related knowledge/attitude/behavior were also examined.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and participants

This study employed a before-and-after method, a type of a non-experimental design, to investigate the effectiveness of the IMP for dementia prevention on cognitive function, depression and QOL of elderly in a public health center. Pretests of cognitive were conducted prior to starting the program (week 0).Pretests for those who had difficulty in visiting public health center in advance were conducted an hour earlier on the first day of the program. Post cognitive tests were conducted on week 8, the last day of the program. A survey of depression and QOL was conducted on the first day (1st week) of the program as a pretest and on the last day (8th week) as a posttest. Participants checked their own survey (as the researcher read each question one by one. Assistants helped respondents who could not follow the researcher's progress.

The selection criteria of the participants were as follows;

Inclusion criteria

-

-

Adults aged 60 and older living in ‘S’ community

-

-

Had not been diagnosed with dementia

-

-

Were able to communicate, listen and perform the program activities

-

-

Agreed to participate in the research

Exclusion criteria

-

-

Diagnosed with dementia or Parkinson's disease and were taking prescribed medicine

2.2. Recruitment and consent

Participants were recruited through notices and advertisements in public health centers, community service centers and local newspapers of ‘S’ community. Recruitment was started one month before the program started.

If people wanted to participate they visited the ‘H’ branch health center for baseline assessment, at which time the researcher explained the purpose and method of the study and participants were asked to sign a written consent. Screening, consent and pretesting were performed face to face by the researcher.

2.3. Integrative medicine program (IMP)

The IMP for dementia prevention was performed from 3 July to 10 November 2017 at ‘S’ community center. The IMP consisted of acupuncture, moxibustion, meditation, activities (physical activities, laughter therapy, music therapy and herb tea therapy), and health education (Supplementary Figure 1). The IMP was conducted once a week for 8 weeks.

2.3.1. Acupuncture and moxibustion

Participants received acupuncture and moxibustion every week except for the 8th week (7 times) from two Doctors of Korean Medicine (DKM). The acupoints treated were GV 20, Ex-HN1 on the head, LI 4, HT 7, and PC 6 on the forearm, and ST 36 and LR 3 on the lower extremities, giving a total of 10 points for each subject. Stainless acupuncture needles (WooJin; 0.20 mm × 30 mm) were inserted vertically through the skin's surface. The acupuncture retention time was 20 minutes.

Acupoints were selected based on previous studies. A review of acupuncture treatment applied to treat amnestic mild cognitive impairment mentioned that the most frequently used acupoints were GV 20, GV 24, GB 20, Ex-HN1. Additionally, another review of acupuncture treatments for dementia revealed that the acupoints used in the included studies were GV 20, GV 24, Ex-HN1, GB 20 (head), BL 18, BL 23(trunk), PC 6, HT 7, KI 3, GB 39, ST 36, ST 40, SP 06, and LR 3.8, 16

Moxibustion was also conducted to relieve physical symptoms and improve QOL of participants. Specifically, an electronic moxa (Onttum) was used at CV4 at 42°C for 20 minutes.

2.3.2. Meditation

Meditation was led by an expert in its use for enhancing cognitive ability. For meditation, participants sat on a mat and listened to calm music while they were led to relax and breathe deeply for 5 minutes. Meditation was also conducted seven times (every week except week 8).

2.3.3. Activities

Physical activities were practiced for one hour biweekly to improve cognitive function. Exercise sessions were explained and demonstrated by the lecturer and by watching videos. The 60-minute exercise program consisted of 25 minutes of stretching and 35 minutes of dementia prevention aerobic exercise developed by the National Health Insurance Service.

Laughter therapy, music therapy and herbal tea therapy were each provided once to relieve stress and reduce depression. Therapy was administered by a laugher therapist, music therapist and DKM.

2.3.4. Health education

Health education was performed three times; dementia, geriatric depression and good lifestyle for well-living in the concept of ‘Yangsaeng (養生)’ for 30–50 minutes. A DKM conducted education regarding dementia and Yangnseng, while a mental health social worker in ‘S’ community mental health center provided geriatric depression education.

2.4. Primary and secondary outcome measurement

The primary outcome measure was cognitive function. Secondary outcome measurements were depression, QOL and knowledge/attitude/preventive action of dementia. We used the Mini Mental State Examination for Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS),17 Digit Span Test (DST) and Trail Making Test (TMT) for cognitive function. For the specific assessment of cognitive function of healthy older adults without diagnosis of dementia DST and TMT were involved as primary cognitive outcome. Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form (GDSSF-K) was used for depression,18 and EQ-5D for QOL.19 In addition, a questionnaire of knowledge/attitude/behavior of dementia was used to assess knowledge, attitude and preventive behavior related to dementia.20

2.4.1. MMSE-DS

Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a recommended instrument for screening dementia and assessing global cognitive function worldwide. However, it has few questions for memory and executive function.21

2.4.2. DST

Digit span, which measures attention, concentration and working memory, is a simple and useful method for assessing elderly patients, particularly those with dementia. The DST has two subtests, digit span forward (DSF) and digit span backwards (DSB). DSF is considered to measure attention and short term memory and DSB to evaluate working memory.22 After listening to a series of numbers read by the investigator, a participant is required to repeat the numbers in the same order in the forward test and in reverse order in the backward test. The raw score is the total number of correctly recalled trials.

2.4.3. TMT

The trail making test measures executive function and attention. It is divided into two tests, A and B. TMT-A is more related to attention and TMT-B is related to executive function.23 TMT-A is used to connect distributed numbers in ascending orders from 1 to 25 and TMT-B is used to link numbers from 1 to 13 and letters from ‘Ga’ to ‘Ta’ (Korean alphabet) alternately.24 In this trial, the Korean version of the TMT was used, which is a subtest of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease Neuropsychological Battery-Korean version (CERAD-K).25 Unlike the CERAD-K, the time was measured until the end, even if it took more than 5–6 minutes.

2.4.4. GDSSF-K

The method used to measure depression in this study was developed by Kee.18 The cut-off point of the GDSSF-K is 5. A total score of 0–4 indicates normal, 5–9 is mild depression symptom, and 10 and over indicates severe depression.

2.4.5. EQ-5D

EQ-5D is a health-related quality of life (HRQOL) tool developed by the EuroQol group. The measurement used in this trial was EQ-5D-3L, which has been used since 2005 in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to measure the national HRQOL. The formula of preference weight for the EQ-5D index used in this study was from Lee's model.26

2.4.6. Survey of knowledge/attitude/behavior of dementia

The survey included in the guideline from the Korea health promotion institute is composed of 12 items for knowledge, eight items for attitude and 10 questions pertaining preventive behavior of dementia.

2.5. Statistical analysis

To investigate the effects of the integrative program, subjects who had more than two absences were excluded in the analysis. Also, tests of those who could not recall the sequences of Korean alphabet and give up finishing the TMT-B was excluded in analyzing trail making test B. Paired t-tests were used to compare pre and post-test data. All data were analyzed using the R program (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The level of significance was set at p = 0.05.

3. Results

After assessment of 93 elder adults, three who took medicine related to dementia and mild cognitive impairment were excluded from the study and another two people refused to participate in the program. Among 88 participants who were allocated to the IMP, 48 completed the program. Thirty eight people did not complete the program and two did not receive the tests (Supplementary Figure 2)

3.1. General characteristics of participants

This study included 48 people (nine males and 39 females). The average age was 71.2. When grouped by education years, seven people (14.6%) had 0–3 years of education, six (12.5%) 4–6 years, 20 (41.7%) 7–12 years and 15 elderly (31.2%) had more than 13 years. Most participants were taking medicines related to chronic diseases and more than 70% of the participants exercised regularly, with exercise occurring on an average of 4.37 days per week (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants

| N = 48 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 9 | 18.8 |

| Female | 39 | 81.2 |

| Age groupa | ||

| <65 | 6 | 12.5 |

| 65–75 | 31 | 64.6 |

| >75 | 11 | 22.9 |

| Religion | ||

| Have religion | 41 | 85.4 |

| No religion | 7 | 14.6 |

| Marital status and spouse | ||

| Married | 27 | 56.2 |

| Widowed/Divorced | 20 | 41.7 |

| Other | 1 | 2.1 |

| Living arrangement | ||

| Living alone | 18 | 37.5 |

| Living with spouse | 17 | 35.4 |

| Living with children | 13 | 27.1 |

| Education perioda | ||

| 0–3 | 7 | 14.6 |

| 4–6 | 6 | 12.5 |

| 7–12 | 20 | 41.7 |

| ≥13 | 15 | 31.2 |

| Diseaseb | ||

| None | 3 | 6.3 |

| Hypertension | 20 | 41.7 |

| Diabetes | 9 | 18.8 |

| Dyslipidemia | 18 | 37.5 |

| Medication | ||

| Yes | 39 | 81.2 |

| No | 9 | 18.8 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 2 | 4.2 |

| No | 46 | 95.8 |

| Drinking | ||

| Yes | 9 | 18.8 |

| No | 39 | 81.2 |

| Exercise | ||

| Yes | 35 | 72.9 |

| No | 13 | 27.1 |

Years.

Plural choices.

3.2. Effectiveness of the program

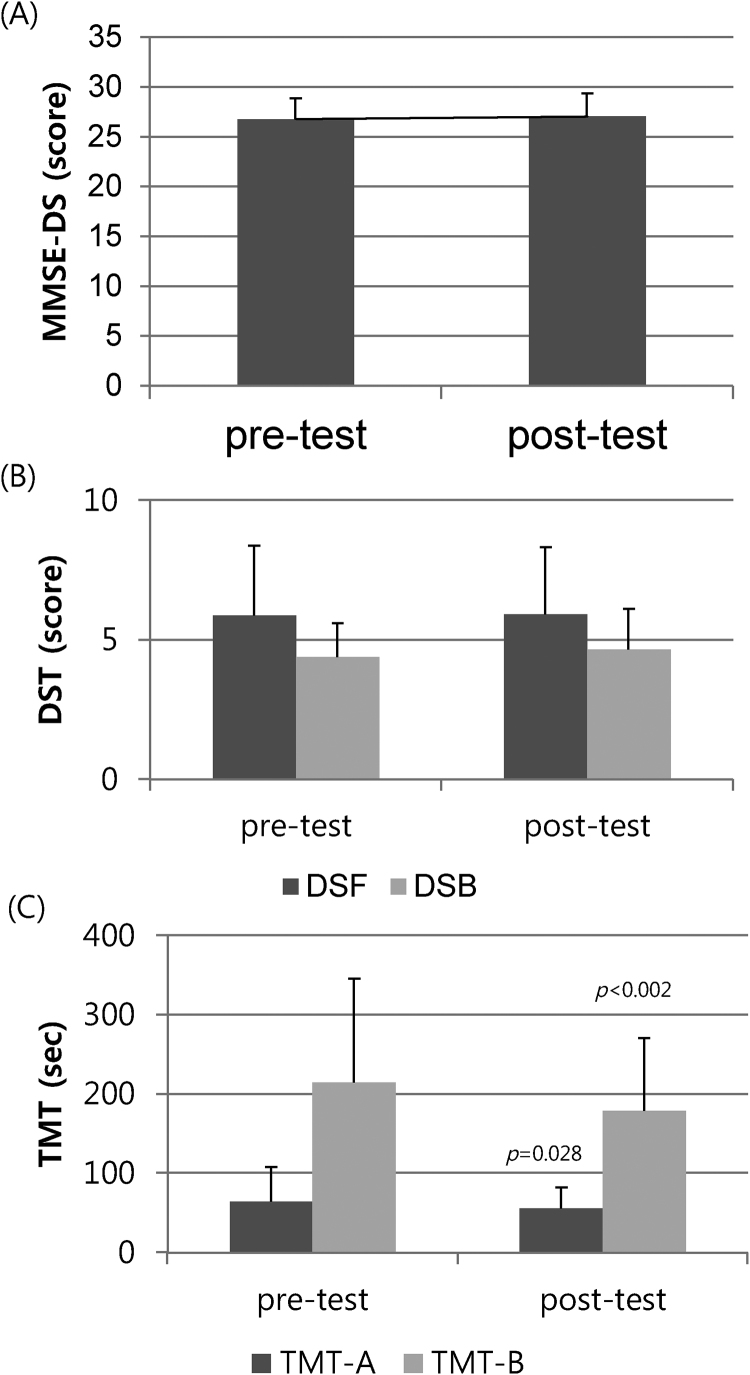

The scores of MMSE-DS (p = 0.31) and DST (DSF: p = 0.85, DSB: p = 0.18) were not significant; MMSE-DS was 26.75 ± 2.09 on pretest and 27.06 ± 2.30 on posttest. DSF was 5.88 ± 2.48 on pretest, 5.92 ± 2.39 on posttest and DSB was 4.38 ± 1.20 on pretest, 4.65 ± 1.45 on posttest. The time of the TMT was significantly reduced by about nine seconds in TMT-A (pretest: 64.73 ± 42.64, posttest: 55.5 ± 26.93, p = 0.03) and 35 seconds in TMT-B (N = 45, pretest: 214.62 ± 130.62, posttest: 179.24 ± 91.07, p = 0.001) on average (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Change in cognitive function. (A) MMSE-DS, (B) DST, (C) TMT. MMSE-DS, Mini Mental State Examination; DSF, digit span forward; DSB, digit span backwards; TMT, trail making test.

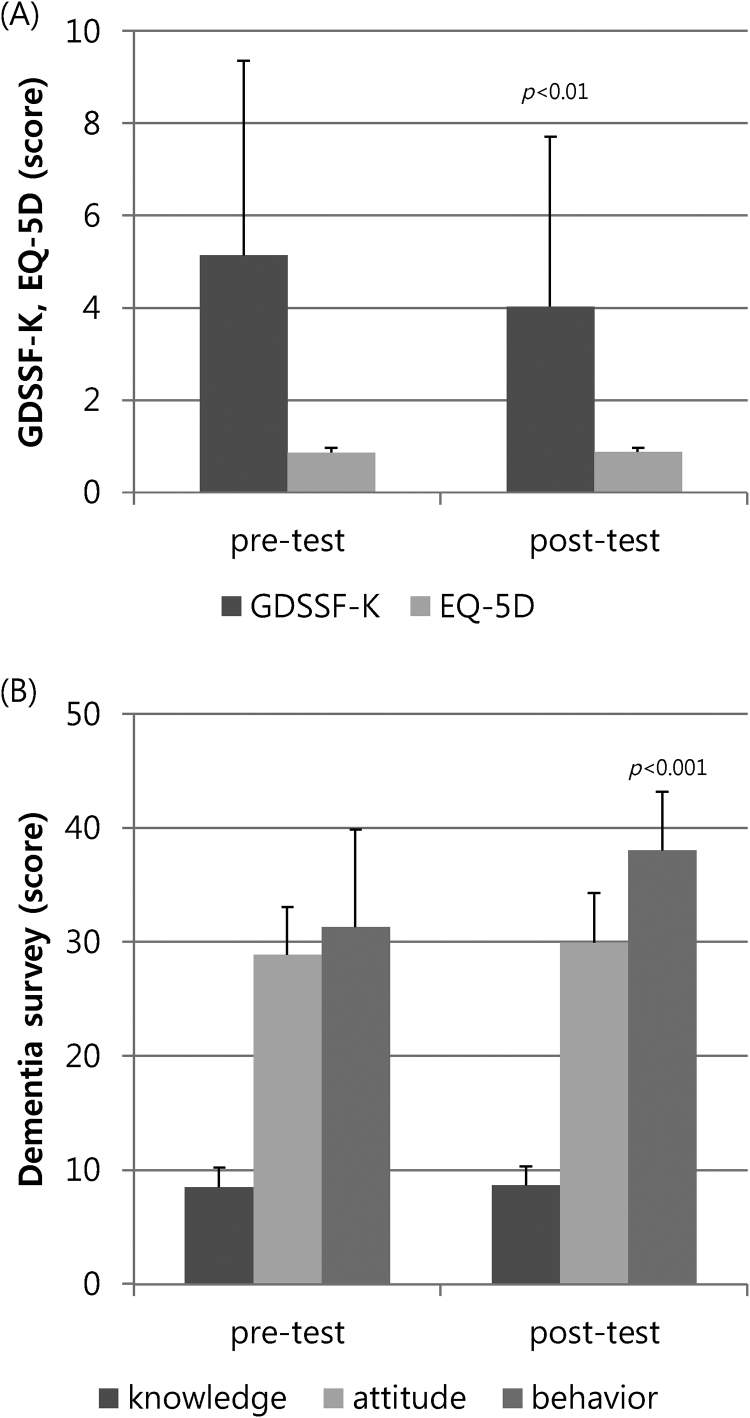

After participation in the program, the score of GDSSF-K decreased significantly (pretest: 5.15 ± 4.21, posttest: 4.04 ± 3.67, p < 0.01) while QOL was slightly changed (pretest: 0.872 ± 0.10, posttest: 0.877 ± 0.09, p = 0.70). Points on the questionnaire about preventive behavior for dementia increased significantly from 31.31 ± 8.55 to 38.04 ± 5.14 (p < 0.0001) even though knowledge (p = 0.35) and attitude (p = 0.15) regarding dementia did not (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Change in depression, quality of life and dementia survey. GDSSF-K; Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form-Korean.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the effectiveness of the IMP for dementia prevention on cognitive function, depression and QOL of community-dwelling adults over 60. Concentrating on the effect on cognitive function, we used three different cognitive measures that evaluate several cognitive functions. Because the subjects of this study were elderly without diagnosis of dementia, the MMSE-DS score was high and it was difficult to increase it further. The average MMSE-DS of the subjects was 26.75 on pre-test, which was higher than those in similar programs that reported improvement of the MMSE score. These findings could be attributed to the average education period of the participants being longer than that of other studies.7, 27 Moreover, because the MMSE is a screening instrument for dementia, it has a limited ability to evaluate enhancement of cognition. Although the scores of the DST did not show remarkable improvement, the time of TMT was shortened significantly. This means the program may have beneficial effects on executive function. For the healthy elderly, four weeks of a combination exercise program had no effect on DST, while the executive function measures were improved.28 Some studies reported that Tai chi improved the time of TMT compared to the control group, indicating the potential to maintain executive function.29, 30 When compared with other studies, shorter intervention periods seem to have influenced our results. Moreover, the Korean version of TMT-B tends to show lower performance than expected because of difficulties recalling the sequences of the Korean alphabet.24

The mean score of the depression decreased from 5.15 in the pre-test to 4.04 in the post-test, which is in the normal range. These findings are similar to those of studies conducted by Song7 and Han31 who also found improvements in depression.

The HRQOL was improved after participating in the program, but not significantly. However, other studies have showed an improved QOL when a different measurement tool and longer intervention duration were used.7, 27, 31

In the survey related to dementia, only the preventive behavior increased significantly. Similarly, IMPs for dementia prevention improved the knowledge, attitude and preventive behavior for dementia.6, 7 We can expect better results if we increase the frequency of education in a follow-up study.

To prevent dementia, it is important to manage the risk factors; namely, physical inactivity, depression, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, smoking and nutrition before onset of the disease.3, 32 Recent studies have applied an integrative approach targeting those factors to delay cognitive decline and the onset of dementia.2, 3 Representative programs include the Seniors Health and Activity Research Program Pilot (SHARP-P), the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER), and a Mutidomain Approach for Preventing Alzheimer's Disease (MAPT). As in this integrated prevention strategy, the IMP in our study was also structured. Acupuncture, exercise and meditation were involved to stimulate cognition, while several therapies and moxibustion were performed to reduce depression and to improve HRQOL. The education provided in the IMP improved the performance of behavior that can delay cognitive decline and prevent dementia. Education is necessary for older adults to perform healthy habits and maintain the effects of the health promotion program.33

It should be noted that this study has several limitations. First, it employed a before-after study design without a control group, which results in a low level of evidence. Therefore, it is difficult to exclude the subject-expectancy effect and placebo effect and to generalize the results of this study. Second, we could not conclude that this IMP was helpful at preventing dementia because the study period was too short and the frequency of interventions is low to observe the probability of conversion to dementia.

In conclusion, the IMP consisted of acupuncture, moxibustion, meditation, activities and health education aimed at preventing dementia for community-dwelling elderly over 60. The IMP for dementia prevention may have beneficial effects on cognition function and depression of elderly. However, a well-designed follow-up study is needed to confirm this conclusion.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Public Institutional Bioethics Committee designated by the MOHW (2017-0933-002).

Funding

The integrative medicine program for dementia prevention in this study was performed as a part of the ‘2017 Seoul Senior Korean Medicine Health Promotion Program,’ which was subsidized by the Health Promotion Division, Citizen Health Department, Seoul.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.imr.2019.04.008.

Supplementary

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Patterson C. Alzheimer's Dis Int; 2018. World Alzheimer Report 2018 – the state of the art of dementia research: New frontiers. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olanrewaju O., Clare L., Barnes L., Brayne C. A multimodal approach to dementia prevention: a report from the Cambridge Institute of Public Health. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2015;1:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakesh G., Szabo S.T., Alexopoulos G.S., Zannas A.S. Strategies for dementia prevention: latest evidence and implications. Therapeut Adv Chron Dis. 2017;8:121–136. doi: 10.1177/2040622317712442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee D.Y., Lee S.J., Kim Y., Kim J., Kim H., Lee H.J. Seoul Metropolitan Center for Dementia: DY Lee; 2014. Review for developing a dementia prevention program 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee J., Kim S., Lee Y., Jang E., Lee S. Overview of relations between concepts of sub-health(Mibyung) and Korean medicine patterns. J Soc of Prev Korean Med. 2012;16:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong H., Park K., Kim Y. The evaluation of the effect to the program for preventing dementia on korean medicine for elderly in community. J Soc Prev Korean Med. 2017;21:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song A.J. Professional Graduate School of Korean Medicine Wonkwang University; Iksan: 2016. Research on the effectiveness of dementia prevention program in korean medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng M., Wang X.F. Acupuncture for amnestic mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Acupunct Med: J Br Med Acupunct Soc. 2016;34:342–348. doi: 10.1136/acupmed-2015-010989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee G.-E., Jeon W.-K., Heo E.-J., Yang H.D., Kang H.-W. The study on the korean traditional medical treatment and system of collaborative practice between korean traditional medicine and western medicine for dementia: based on analysis of questionnaire survey in professional group. J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 2012;23:49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park J.W., Lee B.H., Lee H. Moxibustion in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Alternat Med. 2013;13:247. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun Y.J., Yuan J.M., Yang Z.M. Effectiveness and safety of moxibustion for primary insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Alternat Med. 2016;16:217. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1179-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gard T., Holzel B.K., Lazar S.W. The potential effects of meditation on age-related cognitive decline: a systematic review. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014;1307:89–103. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan M.F., Wong Z.Y., Onishi H., Thayala N.V. Effects of music on depression in older people: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ko H.J., Youn C.H. Effects of laughter therapy on depression, cognition and sleep among the community-dwelling elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11:267–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Youn M.K., Lee J.E., Kim S.K., Lee S.W., Kim J.H., Woo K.O. The effects of oriental herbal tea on the brain function quotient of elders at health facility. J East-West Nurs Res. 2013;19:128–137. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee G., Yang H., Heo E., Jeon W., Lyu Y., Kang H. The current state of clinical studies on scalp acupuncture – treatment for dementia-by search for China literature published from 2001 to 2011 in CAJ (China Academic Journals) J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 2012;23:13–32. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim T.H., Jhoo J.H., Park J.H., Kim J.L., Ryu S.H., Moon S.W. Korean version of mini mental status examination for dementia screening and its’ short form. Psychiatry Investig. 2010;7:102–108. doi: 10.4306/pi.2010.7.2.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 18.Kee B.S. A preliminary study for the standardization of geriatric depression scale short form-Korea version. J Korean Neuropsychiatric Assoc. 1996;35:298–307. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Group T.E. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S., Lee E., Park Y., Chong M., Jang B.-H., Park H. 2015. Development of Korean medicine health promotion program for the elderly: Ministry of Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H.J., Im H. Assessment of dementia. Brain Neurorehabil. 2015;8:11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi H.J., Lee D.Y., Seo E.H., Jo M.K., Sohn B.K., Choe Y.M. A normative study of the digit span in an educationally diverse elderly population. Psychiatry Investig. 2014;11:39–43. doi: 10.4306/pi.2014.11.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seo E.H., Lee D.Y., Kim K.W., Lee J.H., Jhoo J.H., Youn J.C. A normative study of the Trail Making Test in Korean elders. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:844–852. doi: 10.1002/gps.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jang J.-W., Kim K., Baek M.J., Kim S. A comparison of five types of Trail Making Test in Korean elderly. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2016;15:135–141. doi: 10.12779/dnd.2016.15.4.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J.H., Lee K.U., Lee D.Y., Kim K.W., Jhoo J.H., Kim J.H. Development of the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Packet (CERAD-K): clinical and neuropsychological assessment batteries. J Gerontol Ser B: Psycholog Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P47–P53. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.p47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee Y.K., Nam H.S., Chuang L.H., Kim K.Y., Yang H.K., Kwon I.S. South Korean time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states: modeling with observed values for 101 health states. Value Health: J Int Soc Pharmacoeconom Outcomes Res. 2009;12:1187–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park K., Jeong H., So S., Park Y., Yang H., Jung K. The effects of the activity program for preventing dementia against depression, cognitive function, and quality of life for the elderly. J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 2013;24:353–362. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nouchi R., Taki Y., Takeuchi H., Sekiguchi A., Hashizume H., Nozawa T. Four weeks of combination exercise training improved executive functions, episodic memory, and processing speed in healthy elderly people: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Age (Dordr) 2014;36:787–799. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9588-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen M.H., Kruse A. A randomized controlled trial of Tai chi for balance, sleep quality and cognitive performance in elderly Vietnamese. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:185–190. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S32600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mortimer J.A., Ding D., Borenstein A.R., DeCarli C., Guo Q., Wu Y. Changes in brain volume and cognition in a randomized trial of exercise and social interaction in a community-based sample of non-demented Chinese elders. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2012;30:757–766. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-120079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han Y.R., Song M.S., Lim J.Y. The effects of a cognitive enhancement group training program for community-dwelling elders. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2010;40:724–735. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2010.40.5.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Norton S., Matthews F.E., Barnes D.E., Yaffe K., Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer's disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:788–794. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Im M.Y., Mun Y.-H. The effectiveness of health promotion program for the elderly. J Korean Public Health Nurs. 2013;27:384–398. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.