Abstract

Background:

Strong family bonds are part of the Indonesian culture. Family members of patients with cancer are intensively involved in caring, also in hospitals. This is considered “normal”: a societal and religious obligation. The values underpinning this might influence families’ perception of it.

Aim:

To explore and model experiences of family caregivers of patients with cancer in Indonesia in performing caregiving tasks.

Design:

A grounded theory approach was applied. The constant comparative method was used for data analysis and a paradigm scheme was employed for developing a theoretical model.

Setting/participants:

The study was conducted in three hospitals in Indonesia. The participants were family caregivers of patients with cancer.

Results:

A total of 24 family caregivers participated. “Belief in caregiving” appeared to be the core phenomenon. This reflects the caregivers’ conviction that providing care is an important value, which becomes the will power and source of their strength. It is a combination of spiritual and religious, value and motivation to care, and is influenced by contextual factors. It influences actions: coping mechanisms, sharing tasks, and making sacrifices. Social support influences the process of the core phenomenon and the actions of the caregivers. Both positive and negative experiences were identified.

Conclusion:

We developed a model of family caregivers’ experiences from a country where caregiving is deeply rooted in religion and culture. The model might also be useful in other cultural contexts. Our model shows that the spiritual domain, not only for the patient but also for the family caregivers, should be structurally addressed by professional caregivers.

Keywords: Family caregiver, palliative care, Indonesia, grounded theory

What is already known about the topic?

Caring for someone with cancer has a huge impact on family caregivers.

Family caregivers develop strategies to overcome caregiving challenges.

What this paper adds?

This article proposes a conceptual framework of families’ experiences in a country where caring for a family member is obligatory and deeply rooted in religion and culture.

Belief in caregiving is the core factor in the caring process.

We found some new factors in family caregivers’ experiences, including one psychological factor, which is sacrifices, and two social factors, which are sharing care and family cohesiveness.

Implications for practice, theory, or policy

Health care professionals might benefit from assessing and addressing family caregivers’ beliefs in caregiving, sharing care, sacrifices, and positive experiences.

Belief in caregiving is a dynamic concept for family caregiving research, which has the potential to be developed in other cultural settings.

Background

Cancer is the second major cause of death in the world.1 In an advanced stage, people with cancer experience decreased functioning, increased symptom burden, and dependency on others. Consequently, the role of family caregivers increases2 and needs to be recognized as part of the care process.3

Indonesia is one of the Asian countries whose culture is characterized by strong family bonds.4,5 Thus, family caregiving is perceived as obligatory due to cultural norms,6 including moral duty, reciprocal responsibility,6,7 and religious obligation.8,9 On top of this, lack of alternatives, due to inadequate health care services,10 leave the family with no option but to be profoundly involved in providing care.

Studies show that in some Asian countries11–13 culture and norms influence the caregiving process, including caregivers’ motives,7 actions,13 and consequences.14 However, evidence from Asian countries where cultural norms and religion profoundly influence the caregiving process is still under-presented.

Theoretical frameworks about family care provision focus on stress,15–17 the process of caregiving,13,54 or the impact on the caregivers’ health.18 There is still a gap in the knowledge between the basic mechanism of the family caregivers’ actions and the consequences. Therefore, we explored and modeled experiences of family caregivers of patients with cancer in Indonesia. This information might contribute to relieving family burden and enhancing positive experiences.

Methods

Design and setting

Grounded theory, as defined by Strauss and Corbin,19 was used because we aimed to identify categories and to develop a theoretical model to link their relationship. The Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) 32-item checklist was followed for reporting.20 The study was conducted between July 2015 and March 2016 in the outpatient clinics of three hospitals, all assigned by the Ministry of Health of Indonesia to provide palliative care services:21 Dharmais Cancer Hospital (Jakarta), Dr. Soetomo Hospital (Surabaya), and Dr. Sardjito Hospital (Yogyakarta).

Participants and recruitment

General information about potential participants was gathered by the first author (M.S.K.). They were then asked if they were interested to participate in the study. Then, inclusion criteria were applied (Table 1). Various demographic characteristics, including previous experiences of providing care, were considered to give a large variation in the data22 (Table 2). In order to reach theoretical sampling,19 we collected data from three different cities, adapting questions when needed and selecting cases,23 for example, by choosing economically challenged participants as well as wealthy ones. Participants and interviewer had not met before. The participants received comprehensive information about the study procedure and protocol, and signed an informed consent form if they agreed to participate.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Being the spouse, adult-child, or relative who looked after a patient with cancer stages 2–4, or with metastases in any type of cancer Already taking care of the patient for at least 4 months Living with the patient or delivering the care for the patient for at least 3 h a day Being 18 years or older Willing to take part in the study |

| Exclusion criteria | Family caregiver of a patient in an unconscious condition or in a critical physical condition |

Table 2.

Demographic data of the participants and patients.

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Family caregiver gender | |

| Male | 8 (33) |

| Female | 16 (66) |

| Patient gender | |

| Male | 8 (33) |

| Female | 16 (66) |

| Type of relationship with the patient | |

| Husband | 6 (25) |

| Daughter | 11 (46) |

| Wife | 2 (8) |

| Sister | 2 (8) |

| Son | 1 (4) |

| Parent | 1 (4) |

| Brother | 1 (4) |

| Cancer type of the patient | |

| Breast | 4 (16.6) |

| Ovarian | 3 (12.5) |

| Cervix | 3 (12.5) |

| Others | 14 (58.3) |

Data collection

Based on the literature, a topic guide covering the participant’s experiences, tasks, motivations, and challenges and the positive aspects of providing care was developed by all the authors, all experienced in qualitative research. The topic guide, pilot tested with three family caregivers to check the clarity of the questions, was about the participant’s experiences, tasks, motivations, and challenges and the positive aspects of providing care. In-depth interviews in face-to-face sessions were done by M.S.K., which were all audio-recorded. Participants could choose the interview location: a private room in a hospital or their own home. They were offered an opportunity to review their interview transcript. Data were considered saturated when no new codes could be built. We performed two more interviews to check data saturation. After that, data collection was ended.

Data analysis

Interviews were conducted in the Indonesian language and were transcribed verbatim. Data analysis followed the guidelines of the grounded theory of Strauss and Corbin which consists of three steps: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding.19

First, after each interview, open coding was done by line-by-line coding. Codes were immediately built in English to facilitate the involvement of all authors.24 The first eight transcripts were coded independently by three Indonesian authors (M.S.K., A.U., and C.E.) who are fluent in Indonesian and English. Several meetings were conducted with all the authors until consensus on the codebook was reached. The constant comparative method was followed for data collection and analysis.19 The codebook was built alongside the interview sessions and discussed regularly with all the authors. In this step, 221 codes were retrieved. Similar codes were merged resulting in 46 codes, which were then grouped into 12 categories based on their communalities.

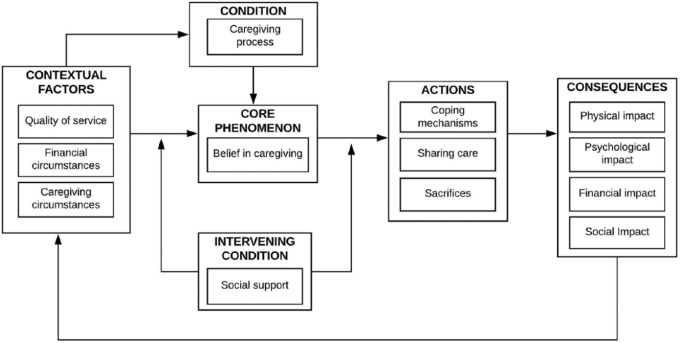

For axial coding, we used the paradigm scheme of Strauss and Corbin19 which provides general building blocks to formulate a specific hypothesis. These blocks are conditions, contextual conditions, intervening conditions, core phenomena, actions, and consequences19 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Terminologies used in the paradigm scheme of grounded theory by Strauss and Corbin.

| Terminology | Definition |

|---|---|

| Context | A set of conditions in which problems/situations arise |

| Condition | A time point under which circumstances an action is happening |

| Core phenomenon | The main theme of the research to which all the other concepts are related |

| Action | The strategy used to deal with issues/conditions |

| Intervening condition | A condition that directly or indirectly influences the core phenomenon |

| Consequences | Outcomes of actions as responses to an event |

Finally, we undertook selective coding, referring to the process of integration and refining the theory (Table 4). A core phenomenon was selected through several team meetings (Figure 1). It must be central and related to all the others, appear frequently in the data, be logical and consistent, have explanatory power, and be able to explain variations.19 During the process of integration, the relation of each category to each other was discussed until the storyline was clearly defined. Finally, the scheme was refined and validated to maintain internal consistency and logic.19 ATLAS.ti 8 was used to organize the data.

Table 4.

Example of the three-phase coding process about belief in caregiving.

| Open codes |

Axial codes | Selective codes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example of quotes | Coding | Category | ||

| “I always believe that it’s better to care for someone than being taking care of, that is why I am doing my best now.” | Value of caregiving | Belief in caregiving | Core phenomena | Belief in caregiving is the center of the phenomenon. It is influenced by contextual factors (quality of service, financial condition, and challenges) and an intervening condition (social support). The core phenomenon influences actions (approach by the family caregivers, coping mechanism) |

| “When she is in pain, I stay with her, comfort her … I believe that the pain will go when she is happy.” | Perception: disease and treatment | |||

| “This is an opportunity for me to secure my place in heaven.” | Religion and spiritualism related to disease and treatment | |||

| “I am glad that I still have the chance to serve him and be a good wife.” | Chance in disguise | |||

| “I am doing it because I love her so much.” “Nobody else is doing it, she has no one but me.” | Reason to care | |||

Figure 1.

A paradigm model of the experiences of family caregivers of patients with cancer in providing care.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Universitas Gadjah Mada and Dr. Soetomo Hospital. All participants received thorough information about their rights to refuse and withdraw at any time with no consequences.

Results

Between July 2015 and March 2016, 28 caregivers were invited, of which 4 refused due to time concerns, leaving 24 who participated (mean duration = 45 min; 30–100 min). Family caregivers were younger (mean = 43) than patients (mean = 55). Four participants had given up their jobs to provide care and only two had previous experiences as a family caregiver.

The core phenomenon

The core phenomenon of this study appeared to be the belief in caregiving. This reflects the caregivers’ conviction that providing care is an important value, which becomes the will power and source of their strength. It is a combination of spiritual and religious values and motivation. The most common reason was the religious belief that a place in heaven is secured when one is willing to take on this role:

It’s my task as a daughter. I also have a chance to do good things and save my place in heaven doing this job. (P19, Daughter)

Participants revealed their deeply held beliefs and practiced prayer rituals more frequently and more intensively than they used to do before they became a caregiver. Some perceived disease as a punishment or a sign of love from God:

It is a lesson for what we have done in the past. We take advantage to “clean ourselves up” now and we will have a place in heaven later. (P9, Husband)

Apart from religion, some normative values strengthened their belief in caregiving such as “it’s better to care for someone than being sick yourself,” “better to give than to get,” and “it’s our duty to fight until the end.” Many perceived the dependency of the patient as a “chance in disguise,” offering them an opportunity to look after the person and to show how much they care.

Most adult children and spouses considered it an “obligatory” task, but this was framed positively. Due to their religion, the participants believed that they would be rewarded in their future life. Some were simply asked by the patient and felt honored to be asked. However, several said that they had no other choice and showed their resentment.

Contextual factors

Quality of service

People with advanced cancer are referred to tertiary hospitals which are usually hectic. Many participants had complaints about the quality of the health care services and the administration process. Some who lived far from the hospital faced challenges related to transport and accommodation:

My wife was in pain at midnight. I needed to borrow my neighbor’s car. The hospital was an hour away, and only a trainee doctor was available. We needed a consultation with our medical specialist, but he was on duty in a private hospital where I couldn’t use my insurance. I went to this private hospital, he gave me a prescription, brought the drug, then my wife received treatment. (P9, Husband)

Participants reported the lack of support from health care professionals, particularly in relation to the amount of time the professionals gave them. Some reported that they lacked information about the patient’s treatment and prognosis.

Financial circumstances

Family caregivers spent much money for patients’ treatment and care. These were extra expenses for treatments which were not covered by the national insurance, such as certain drugs, or some diagnostic procedures, travel costs, and accommodation (if they needed to stay overnight before or after chemotherapy). Their financial circumstances also reflected how they managed the expenses, for example, some asked family and relatives for contributions. In some cases, adult children of the patients handled the financial arrangements.

Caregiving circumstances

With regard to practical arrangements, there were some conflicts between the carer and the patient or other family members. For example, participants often put a lot of effort into preparing meals as a way to show love, which could cause tension when the patient lost his appetite:

I cooked many types of meals, but he didn’t even taste it. He lost lots of weight; I don’t want people thinking that I can’t look after him. (P10, Daughter)

The ignorance of other family members of the details of caring became a typical problem, especially for adult children who sometimes felt that their siblings did not make an equal effort. Meanwhile, family expectations of the caregiver were sometimes regarded as too high.

Intervening condition

Social support

Participants identified social support as a valuable back-up. For example, female caregivers found the blessing of their husbands to be essential. Practical support which decreased burden was received from friends, family, social networks, and workplaces:

When my husband has chemo, my friend will pick my daughters up and look after them. That’s really a big help. (P13, Wife)

Actions

Coping mechanisms

Constructive coping was frequently applied by, for example, finding social and spiritual support, seeking information, balancing and adjusting their lifestyles, and accepting the situation:

I keep doing other things, like an aerobic class, for relaxing. (P8, Wife)

There were also participants who applied less constructive coping mechanisms, like ignoring the problem and apportioning blame. They realized that they used these less productive mechanisms on a temporary basis to release their stress. They also reported efforts to suppress their negative emotions in front of the patient.

Family caregivers of elderly patients in particular concealed the diagnosis and prognosis at the beginning and sought the right moment to inform the patient. Certain issues, such as death and future care planning, were not discussed within the family.

Sharing care

Family caregivers expressed a sense of togetherness when performing care. This not only emerged from the division of tasks between family members but was also reflected in their willingness to offer as well as to receive help from others. The participant was often not the only caregiver in the family. Everyone contributes in whatever way they could, for example, those with money tend to take charge of financial matters, while others would dedicate more time and energy:

My brother pays for transportation and I accompany mom on hospital visits. I look after her for breakfast and lunch, he for dinner. (P24, Daughter)

Sacrifices

Sacrifices are defined as caregivers giving up something in order to focus on or meet the patients’ needs. The patient becoming the center of attention, family caregivers would compromise their own needs and preferences in order to fulfill the patients’ ones.

Some caregivers revealed that they adjusted their career plans or gave up jobs when becoming a caregiver. Others also made sacrifices by working overtime to provide more money to fulfill their financial needs, while some left their own families, living in different cities, to provide care. These sacrifices were mostly made voluntarily, because they considered those as the right things to do as part of their duty:

It was hard to leave my job, but I will find one again, once I am finished with this. It’s the way it is as a family. (P18, Sister)

Consequences

Physical impact

Most elderly participants reported physical impact such as tiredness or a tendency to ignore their own physical condition as a result of their caring activities.

Psychological impact

Psychological impact can be either positive or negative. Looking after someone with cancer leaves the carer with constant fears and worries that the patient will die. They were constantly in a state of alertness even when diagnostic tests showed good progress. This left them with no rest and tiredness. They were also affected emotionally by the suffering of the patient, especially when that person was their partner or someone with whom they had a good relationship:

Seeing her like that is too painful for me. (P15, Daughter)

On the other hand, some experiences left them with new values in their personal lives; most felt that they had done the right thing by taking on the responsibilities of caring, which resulted in positive self-regard. Some said that being a carer had made them a better person:

I am needed. When I can put a smile on her face, that gives me lots of joy. I have never felt as good as this before. (P22, Daughter)

Financial impact

Providing the best care for the patient had impact on the financial situation of the family caregivers. This caused troubles not only for economically challenged families, but also for the wealthier families because they were used to a higher standard of care.

Social impact

Participants identified positive changes in their personal lives, for instance, gaining new values and improving cohesiveness of the family:

I have four siblings, all married. Now, due to mom’s condition, we spend much more time together than we were used to. I feel so close to them now. (P20, Daughter)

The paradigm scheme

As illustrated in Figure 1, the condition in this study was the caregiving process, by a family caregiver to a loved one with cancer. The tasks varied from assisting in daily activities and personal hygiene, hospital arrangements, and meal and drug preparations to providing emotional support. This condition was influenced by contextual factors (Table 5).

Table 5.

Linkage between one category and another in the paradigm scheme through examples of quotes.

| Link between one category and another category | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Contextual factors influence the condition | “Things that make it harder are when I need to deal with a long queue in the hospital and find a parking spot. I need to drop her in a wheel chair at the front door of the hospital and leave her alone, because I have to find a parking spot for 30 minutes or more.” (P21, Husband) |

| Conditions influence the belief in caregiving | “I don’t know how much mom knows about the condition of my father. She only knew that he has a tumor, but I don’t think she knows that it is cancer. She doesn’t really understand and I don’t think that she can handle the reality. She never comes with dad for control and chemo, because she is too scared. I am scared too but we need somebody to be with dad, so I am here.” (P11, Daughter) |

| Belief in caregiving influences actions | “I am still young and I can find another job, but I may only have one chance to look after mom. I resigned to become her full time caregiver. This is my real duty as a son.” (P3, Son) |

| Actions influence consequences | “I used to talk maybe once in a while with my siblings, we were too busy doing our own stuff. But since mom got sick, I am talking to them every day. I feel like we are united.” (P22, Daughter) |

| Actions influence contextual factors | “I used to say ‘no’ to any offer, because I thought the husband should be responsible for everything. One time, I got so tired and tense. Then I received an offer from my nephew to replace me so that I can do my hobby, golf, for 2 hours. I came back in a very happy mood and it makes my wife happier as well. I am glad to have taken that offer; I golf once a week now.” (P14, Husband) |

| Social support influences actions | “I have two sisters, but they do not want to get near mom due to the smell of the wound. I am doing everything including cleaning mom’s wound twice a day and washing her clothes. My husband is a miracle, he helps me a lot. My brother lives in another town but he stays in contact every time; he is also responsible for all the payment. Without them, I would not be able to handle this situation.” (P17, Daughter) |

The core phenomenon appeared to be belief in caregiving. This involves the values and perception of the family caregiver toward the caring process, the strength of will to maintain their determination, and their devotion to being a caregiver. This has consequences in the physical, psychological, financial, and social domains experienced by family caregivers as a result of their actions, as well as on the caring process itself. These consequences might eventually influence the contextual factors of care, like a new cycle.

There appeared to be one intervening condition: social support. This seemed to influence the relationship between contextual factors and the core phenomenon, and between the core phenomenon and actions. In this case, when the caregivers received sufficient support, their capacity to tackle challenges increased. On the other hand, when adequate social support was lacking, carers would handle problems using less constructive strategies.

Discussion

We explored the experiences of family caregivers of people with cancer in Indonesia and developed a model for the family caregivers’ experiences. We found both negative and positive experiences. Belief in caregiving appeared to be the core phenomenon and involves values and faith, both spiritual and religious, and the caregivers’ motivation for providing care. Belief in caregiving appeared to be influenced by conditional and contextual factors, including the quality of service, finances, and the circumstances of care. The core phenomenon influences the actions of caregivers and has physical, psychological, financial, and social impacts.

Previous qualitative studies on family care provision did not report “belief in caregiving” as a major factor. They focused on the stress experienced by family caregivers,15–17 the care process itself,13 or the impact on the caregivers’ health.18

Our model shows some similarities with previous theoretical frameworks on family caregiving research. First, our findings confirmed a previous study that the actions of family caregivers depend on “commitment.”13 It is the driving force behind the performance of care tasks. However, in our study, belief in caregiving has spiritual and religion aspects which have not been previously described. Second, social support has also been recognized before as an influencing factor in care provision.13,15,16,18 Third, strategies in care provision have been described, including the use of cognitive behavioral responses17 and the focus on the needs of patients.13 Finally, the physical15,17,18 and psychological13,15,17 consequences of care provision have also been reported in earlier studies.

While most factors within our model have been identified in previous research on family caregiving experiences which include motives,7,13,25 problems and challenges,13,14,26–35 actions and strategies,13,30,36,37 consequences,13,18,31,32,38,39,54 and social support in caregiving,13,40,41 we found some new factors in strategies and consequences: sharing care, making sacrifices, and family cohesiveness. Our study also confirms that financial circumstances can be described both as a condition and as a consequence. As a condition, this is in line with previous studies which show that treatment and care expenses for cancer are costly.34,35,42 In fact, our previous study in Indonesia showed that financial challenges of caregivers of patients with cancer were greater than those of caregivers of patients with dementia.43 Our study also confirms previous findings that providing care can also have indirect negative financial consequences, such as a reduction of the caregiver’s time spent at work or at other productive tasks.35

Furthermore, our study confirms previously described motives for caring: affection, reciprocity,7 and a lack of alternatives.10 The term “obligation” was frequently used by our participants, but with a positive connotation. It refers to the intrinsic motivation to receive “pahala” (rewards), which is highly valued by themselves and their community.9,43 This aligns with a previous study which found that feeling an obligation is used as a trigger at the beginning, while reciprocity seemed to maintain the motivation.7

The core phenomenon in our study, belief in caregiving, especially its spiritual and religious elements, has also been explored in non-Asian settings,27,44–48 suggesting that this subject is also relevant to other settings and cultures. Spirituality and religion have been widely explored in patients and in health care providers,49–51 and in some previous family caregiving studies.45,49,52 Religion has a central role in everyday life for many Indonesian people.8 Our study revealed that caregivers pray more intensively and more frequently than they did before, which confirms previous findings that religion and spirituality are used as a coping mechanism.8,47,48 In fact, those who use positive religious coping reported higher caregiver satisfaction than those who did not use such coping.48

Strengths and limitations

We complied with the grounded theory rules, including the constant comparative method.19 Using its paradigm scheme, the model of family caregivers’ experiences in Indonesia could be presented in an integrated and structured way. However, although we tried to provide a comprehensive description of family caregivers’ experiences, there are some limitations. We did not include caregivers of patients who had been recently diagnosed or those in the bereavement phase. Therefore, some aspects might have been overlooked. None of the participants indicated any interest in reviewing their interview transcript. Finally, while a lot of effort has been taken, some culture-bound meanings and connotations of words might have been lost in translation.53

Conclusion and recommendation

Belief in caregiving, including values, motives, spirituality, and religion, all being universal elements, appeared to be the core phenomenon in the family caregiving model. The central role of belief in caregiving has not been described in previous theoretical frameworks. Although spiritual/existential care is one of the four domains of palliative care, not only for patients but also their family caregivers,3 it tends to be overlooked in clinical practice and research. Next, sharing care, sacrifices, and family cohesiveness, factors not included in previous theories, need to be further explored in order to provide more understanding of family caregivers’ experiences. Therefore, our model could potentially enrich theories in family caregiving research. Finally, family caregivers might benefit from assessing and addressing their own beliefs in caregiving, sharing care, making sacrifices, and positive experiences.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the family caregivers who were willing to share their stories. The authors also thank Dr Probo Suseno, Sp.PD-KGer(K) (Sardjito Hospital, Yogyakarta), Dr Maria Witjaksono, M. Pall(FU) (Dharmais Cancer Hospital, Jakarta), Dr Agustina Konginan, Sp.KJ(K) (Dr. Soetomo Hospital, Surabaya), and head nurses (Ibu Kaning, Ibu Rugaiyah Suster Ame and Sus) for their assistance during the data collection process.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee (MHREC), Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada—Sardjito Hospital (KE/FK/744/EC/2015) and the Ethical Committee in Health Research of Dr. Soetomo General Hospital, Surabaya (N0: 46/Panke.KKE/I/2016).

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Netherland Fellowship Programme (contract number 09963), as part of their PhD study.

Informed consent: All participants provided informed consent.

ORCID iD: Martina Sinta Kristanti  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6609-6285

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6609-6285

References

- 1. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups,1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3(4): 524–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rolland JS. Cancer and the family: an integrative model. Cancer 2005; 104(11 Suppl.): 2584–2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care, 2002, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 4. Effendy C, Vissers K, Tejawinata S, et al. Dealing with symptoms and issues of hospitalized patients with cancer in Indonesia: the role of families, nurses, and physicians. Pain Pract 2015; 15(5): 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schroder-Butterfill E, Fithry TS. Care dependence in old age: preferences, practices and implications in two Indonesian communities. Ageing Soc 2014; 34(3): 361–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kanbara S, Taniguchi H, Sakaue M, et al. Social support, self-efficacy and psychological stress responses among outpatients with diabetes in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2008; 80(1): 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. del-Pino-Casado R, Frias-Osuna A, Palomino-Moral PA. Subjective burden and cultural motives for caregiving in informal caregivers of older people. J Nurs Scholarsh 2011; 43(3): 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rochmawati E, Wiechula R, Cameron K. Centrality of spirituality/religion in the culture of palliative care service in Indonesia: an ethnographic study. Nurs Health Sci 2018; 20(2): 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ibrahim K, Songwathana P. Cultural care for people living with HIV/AIDS in Muslim communities in Asia: a literature review. Int J Nurs Res 2009; 13: 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rochmawati E, Wiechula R, Cameron K. Current status of palliative care services in Indonesia: a literature review. Int Nurs Rev 2016; 63(2): 180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Funk LM, Allan DE, Stajduhar KI. Palliative family caregivers’ accounts of health care experiences: the importance of “security.” Palliat Support Care 2009; 7(4): 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liu WT, Kendig H. Critical issues of caregiving: East-West dialogue. Who should care for the elderly 2000: 1–23, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265758211_Critical_Issues_of_Caregiving_East-West_Dialogue

- 13. Mok E, Chan F, Chan V, et al. Family experience caring for terminally ill patients with cancer in Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs 2003; 26(4): 267–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nemati S, Rassouli M, Ilkhani M, et al. Perceptions of family caregivers of cancer patients about the challenges of caregiving: a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 2018; 32: 309–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, et al. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990; 30(5): 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sherwood P, Given B, Given C, et al. Caregivers of persons with a brain tumor: a conceptual model. Nurs Inq 2004; 11(1): 43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fletcher BS, Miaskowski C, Given B, et al. The cancer family caregiving experience: an updated and expanded conceptual model. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012; 16(4): 387–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, et al. Cancer and caregiving: the impact on the caregiver’s health. Psychooncology 1998; 7(1): 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19(6): 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. Tentang: Kebijakan Perawatan Paliatif; No 812/Menkes/SK/VII/2007, 2007, http://dinkes.surabaya.go.id/portal/files/kepmenkes/skmenkes812707.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robinson OC. Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: a theoretical and practical guide. Qual Res Psychol 2014; 11: 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Butler AE, Copnell B, Hall H. The development of theoretical sampling in practice. Collegian 2018; 25: 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson JK, Barach P, Vernooij-Dassen M. Conducting a multicentre and multinational qualitative study on patient transitions. BMJ Qual Saf 2012; 21(Suppl. 1): i22–i28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim Y, Carver CS, Cannady RS. Caregiving motivation predicts long-term spirituality and quality of life of the caregivers. Ann Behav Med 2015; 49(4): 500–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carlander I, Sahlberg-Blom E, Hellstrom I, et al. The modified self: family caregivers’ experiences of caring for a dying family member at home. J Clin Nurs 2011; 20(7–8): 1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR, et al. Family caregiving challenges in advanced colorectal cancer: patient and caregiver perspectives. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24(5): 2017–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Persson C, Sundin K. Being in the situation of a significant other to a person with inoperable lung cancer. Cancer Nurs 2008; 31(5): 380–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stamataki Z, Ellis JE, Costello J, et al. Chronicles of informal caregiving in cancer: using “The Cancer Family Caregiving Experience” model as an explanatory framework. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22(2): 435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sutherland N. The meaning of being in transition to end-of-life care for female partners of spouses with cancer. Palliat Support Care 2009; 7(4): 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leow MQ, Chan SW. The challenges, emotions, coping, and gains of family caregivers caring for patients with advanced cancer in Singapore: a qualitative study. Cancer Nurs 2017; 40(1): 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gaugler JE, Eppinger A, King J, et al. Coping and its effects on cancer caregiving. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21(2): 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coolbrandt A, Sterckx W, Clement P, et al. Family caregivers of patients with a high-grade glioma: a qualitative study of their lived experience and needs related to professional care. Cancer Nurs 2015; 38(5): 406–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brazil K, Bainbridge D, Rodriguez C. The stress process in palliative cancer care: a qualitative study on informal caregiving and its implication for the delivery of care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2010; 27(2): 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Balfe M, Butow P, O’Sullivan E, et al. The financial impact of head and neck cancer caregiving: a qualitative study. Psychooncology 2016; 25(12): 1441–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stajduhar KI, Funk L, Outcalt L. Family caregiver learning how family caregivers learn to provide care at the end of life: a qualitative secondary analysis of four datasets. Palliat Med 2013; 27(7): 657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ward-Griffin C, McWilliam CL, Oudshoorn A. Relational experiences of family caregivers providing home-based end-of-life care. J Fam Nurs 2012; 18(4): 491–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hashemi-Ghasemabadi M, Taleghani F, Yousefy A, et al. Transition to the new role of caregiving for families of patients with breast cancer: a qualitative descriptive exploratory study. Support Care Cancer 2016; 24(3): 1269–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beng TS, Guan NC, Seang LK, et al. The experiences of suffering of palliative care informal caregivers in Malaysia: a thematic analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2013; 30(5): 473–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Selman LE, Beynon T, Radcliffe E, et al. “We’re all carrying a burden that we’re not sharing”: a qualitative study of the impact of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma on the family. Brit J Dermatol 2015; 172: 1581–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cavers D, Hacking B, Erridge SE, et al. Social, psychological and existential well-being in patients with glioma and their caregivers: a qualitative study. CMAJ 2012; 184(7): E373–E382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Plotti F, Terranova C, Montera R, et al. Economic impact among family caregivers of advanced ovarian cancer patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2014; 24: 90–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kristanti MS, Engels Y, Effendy C, et al. Comparison of the lived experiences of family caregivers of patients with dementia and of patients with cancer in Indonesia. Int Psychogeriatr 2018; 30(6): 903–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Linderholm M, Friedrichsen M. A desire to be seen: family caregivers’ experiences of their caring role in palliative home care. Cancer Nurs 2010; 33(1): 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ferrell BR, Baird P. Deriving meaning and faith in caregiving. Semin Oncol Nurs 2012; 28(4): 256–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nemati S, Rassouli M, Ilkhani M, et al. The spiritual challenges faced by family caregivers of patients with cancer: a qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract 2017; 31(2): 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Asiedu GB, Eustace RW, Eton DT, et al. Coping with colorectal cancer: a qualitative exploration with patients and their family members. Fam Pract 2014; 31(5): 598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pearce MJ, Singer JL, Prigerson HG. Religious coping among caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients: main effects and psychosocial mediators. J Health Psychol 2006; 11(5): 743–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Edwards A, Pang N, Shiu V, et al. The understanding of spirituality and the potential role of spiritual care in end-of-life and palliative care: a meta-study of qualitative research. Palliat Med 2010; 24(8): 753–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Balboni MJ, Sullivan A, Enzinger AC, et al. Nurse and physician barriers to spiritual care provision at the end of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 48(3): 400–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Sinclair S, Pereira J, Raffin S. A thematic review of the spirituality literature within palliative care. J Palliat Med 2006; 9(2): 464–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med 2004; 18(1): 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Squires A. Language barriers and qualitative nursing research: methodological considerations. Int Nurs Rev 2008; 55(3): 265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brown MA, Stetz K. The labor of caregiving: a theoretical model of caregiving during potentially fatal illness. Qual Health Res 1999; 9(2): 182–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]