Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Intravenous (IV) and intramuscular (IM) antibiotics have comparable efficacy in treating neonates undergoing sepsis evaluations. There are no clinical data favoring the use of either route regarding newborn pain and parental preferences. We hypothesized that pain associated with IM injections would worsen breastfeeding effectiveness and decrease parental satisfaction, making IV catheters the preferred route.

METHODS:

This prospective cohort study took place in an academic institution with nurseries in 2 separate hospitals, 1 providing IV antibiotics, and the other, IM antibiotics. Newborns receiving 48 hours of antibiotics were compared by using objective pain and breastfeeding scores and parental surveys.

RESULTS:

In 185 newborns studied, pain scores on a 7-point scale were up to 3.4 points higher in the IM compared with the IV group (P < .001). Slopes of repeated pain scores were 0.42 ± 0.08 and −0.01 ± 0.11 in the IM and IV groups, respectively (P = .002). Breastfeeding scores were similar between groups. Parents in the IV group were less likely to perceive discomfort with antibiotic administration (odds ratio [OR] 0.22; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.06–0.74) but more likely to perceive interference with breastfeeding (OR 26; 95% CI 6.4–108) and bonding (OR 101; 95% CI 17–590) and more likely to prefer changing to the alternate route (OR 6.9; 95% CI 2.3–20).

CONCLUSIONS:

IM antibiotics in newborns are associated with pain sensitization and greater pain than IV dosing. Despite accurately recognizing newborn pain with the IM route, parents preferred this to the IV route, which was perceived to interfere with breastfeeding and bonding.

Current guidelines suggest initiating antibiotics for neonates at risk for early-onset sepsis.1 The common regimen of ampicillin and gentamicin can be administered via intravenous (IV) infusion or intramuscular (IM) injection, with comparable efficacy2–5; however, no evidence exists to guide this clinical decision regarding patient comfort and parental preferences.

The 2016 American Academy of Pediatrics policy update on neonatal pain links repeated painful stimuli to neurodevelopmental sequelae.6,7 Whereas some determinants of early pain perception can be ascribed to maternal characteristics, others are iatrogenically imposed. For example, maternal hypertension was found to be associated with hypoalgesia in neonates receiving vitamin K injections.8 Conversely, newborns of mothers with diabetes had hyperalgesia during venipunctures for newborn screening after undergoing multiple heel lances for glucose monitoring.9 Intuitively, IM injections for repeated antibiotic dosing cause greater neonatal pain than a single IV insertion, but a comparison of relative pain by route is lacking.

We sought to determine if IM antibiotic injections cause greater pain than IV infusions and whether this affects breastfeeding, bonding, and parental satisfaction. We hypothesized that IM antibiotics for neonatal sepsis management would be associated with increased pain, leading to impaired breastfeeding and bonding and to overall parental preference for the IV route.

Methods

This prospective cohort study took place at an academic institution with 2 separate nurseries located 4 miles apart that operate under the same nursing leadership, pediatrics department, and health system. On the basis of long-standing nursing practices, newborns at risk for sepsis receive IV antibiotics at 1 site (IV site) and IM antibiotics at the other (IM site). Infants receiving IV antibiotics are taken to the nursery for the duration of the infusion for closer monitoring, whereas IM antibiotics are administered in the parents’ rooms.

We studied patients admitted to either newborn nursery from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016. Newborns receiving a 48-hour course of antibiotics for suspected neonatal sepsis were included. Newborns who received longer or shorter courses or were transferred from the nursery for higher levels of care were excluded. Antibiotic route was not randomly assigned because it was determined by admission site. As such, neither the participants nor researchers were blinded. Before data collection, we obtained approval by our institutional review board. Data were secured by using Research Electronic Data Capture software.

We collected baseline characteristics, including gestational age, sex of the neonate, pertinent maternal medical comorbidities, and maternal socioeconomic data. We trained bedside nurses at both sites to assess pain and breastfeeding using validated tools. They measured pain on the Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS), which ranges from 0 to 7, within 30 minutes after each dose of antibiotic or after each IV catheter insertion attempt.10 If infants were transitioned from the IV to IM route because of failure to maintain the IV catheter, the NIPS scores associated with IM injections were excluded from the per-protocol analysis. During the breastfeeding session after each antibiotic dose, nurses measured breastfeeding effectiveness using the latch, audible swallowing, type of nipple, comfort of mother, hold or positioning (LATCH) score, which ranges from 0 to 10.11

We developed a survey to evaluate parental experience related to antibiotic route. Survey questions were used to assess perceptions of whether antibiotic administration caused newborn discomfort, interfered with feeding, or interfered with bonding. Overall parental preference for their infant’s antibiotic route was also assessed. Answer options were “yes,” “no,” and “unsure,” followed by an optional comments section for each question. Parents of all newborns who met inclusion criteria were approached to participate in the survey. Those who provided informed consent completed the survey on a computer within the patient’s room without investigators present.

Descriptive statistics were reported as median (interquartile range) or mean ± SD for numerical variables and as frequency count (percent) for categorical variables. The 2-sample t test, χ2 test, or Wilcoxon rank sum test was used, as appropriate, for comparison between sites. To evaluate for pain sensitization with repeated stimuli, we fitted a mixed-effects model to route and dose number and their interaction on NIPS scores. To determine the survey sample size, we assumed that the proportion of parents in the IV group preferring the IV route would be 0.8. The proportion in the IM group was assumed to be 0.8 under the null hypothesis and 0.5 under the alternative hypothesis. Using the 2-sided Z test with pooled variance, we calculated that 39 surveys from each group would achieve 80% power to detect a difference of 0.3 between the group proportions. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the survey data by using logistic regression with Firth’s penalized maximum likelihood estimation. “Unsure” responses were coded as “no.” We deemed P <.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, 1196 newborns were admitted to the nursery at the IV site, and 1714 were admitted at the IM site. Of these, 64 newborns from the IV site and 121 from the IM site met criteria and were included in the objective portion of the study. The patients at both sites were similar in gestational age, sex, presence of maternal hypertension, presence of maternal diabetes mellitus, maternal age, maternal marital status, and maternal ethnicity. Mothers at the IV site were more likely to prefer English as their primary language and have private insurance (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| IV Site (n = 64) | IM Site (n = 121) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infant | |||

| Gestational age at birth, mean ± SD, wk | 39.8 ± 1.2 | 39.8 ± 1.5 | .77 |

| Sex (male:female), n (%) | 33 (52):31 (48) | 57 (47):64 (53) | .56 |

| Maternal comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 8 (13) | 18 (15) | .66 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4 (6) | 10 (8) | .77 |

| Maternal socioeconomic data | |||

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 32.2 ± 4.2 | 32.7 ± 5.1 | .62 |

| Marital status, married, n (%) | 54 (84) | 91 (75) | .15 |

| Ethnicity, white, n (%) | 25 (39) | 35 (29) | .16 |

| Primary language, English, n (%) | 63 (98) | 104 (86) | .01 |

| Insurance, private, n (%) | 61 (95) | 82 (68) | <.01 |

LATCH scores were collected for 61 patients at the IV site and for 113 patients at the IM site because some infants were bottle-fed. The median number of IV attempts was 1 per newborn, with a maximum of 7 attempts for 1 infant. Fourteen (22%) newborns in the IV group were transitioned to IM antibiotics because of catheter displacement.

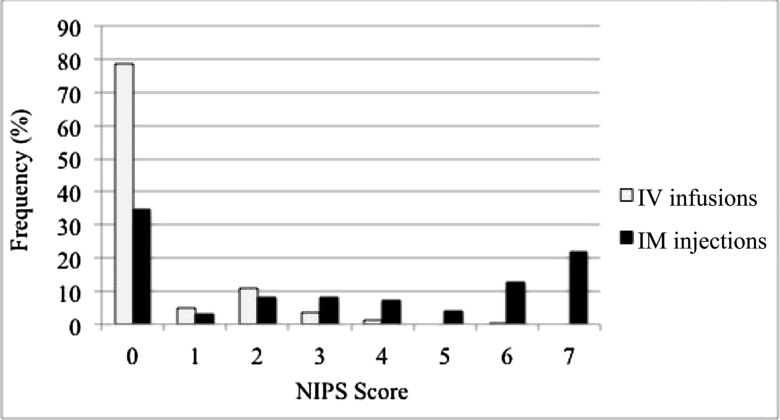

The distribution of NIPS scores by antibiotic route is presented in Fig 1, which reveals higher scores in the IM group. By the fourth pain assessment, we observed a significant difference of NIPS scores between the IM and IV groups (3.8 ± 0.19 and 0.4 ± 0.27; P < .001). The mixed-effects model fitted to route and dose number and their interaction on NIPS scores revealed a significant difference in slope over time between the IM (0.42 ± 0.08; P < .001) and IV groups (−0.01 ± 0.11; P = .93; route interaction effect P = .002).

FIGURE 1.

Frequency distribution of NIPS scores by antibiotic route.

Parents of 40 newborns from the IV site and parents of 67 newborns from the IM site consented to and completed the survey (Table 2). Parents in the IV group were more likely to prefer a change to the other route of administration (OR 6.9; 95% CI 2.3–20) despite perceiving discomfort after antibiotic administration less often than those in the IM group (OR 0.22; 95% CI 0.06–0.74). Parents in the IV group were also more likely to report that antibiotic administration interfered with feeding (OR 26; 95% CI 6.4–108) and bonding (OR 101; 95% CI 17–590). In common remarks, parents stated that taking infants from the room for IV antibiotic administration caused unwanted separation and that the arm-board used to secure the IV catheter interfered with feeding. However, LATCH scores revealed no difference in breastfeeding efficacy between the IM and IV groups (8 [8–9] and 9 [8–9]; P = .06).

TABLE 2.

Parental Survey Results by Antibiotic Route

| IV Site (n = 40) | IM Site (n = 67) | P | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No or Unsure, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No or Unsure, n (%) | |||

| I would have preferred antibiotics given through the alternative route. | 15 (37.5) | 25 (62.5) | 5 (7.5) | 62 (92.5) | <.001 | 6.9 (2.3–20) |

| My infant seemed uncomfortable or fussier after each antibiotic dose or IV insertion. | 3 (7.5) | 37 (92.5) | 20 (29.9) | 47 (70.1) | .01 | 0.22 (0.06–0.74) |

| The setup or process of giving the antibiotic interfered with feeding my infant. | 20 (50) | 20 (50) | 2 (3) | 65 (97) | <.001 | 26 (6.4–108) |

| The setup or process of giving the antibiotic interfered with bonding with my infant. | 28 (70) | 12 (30) | 1 (1.5) | 66 (98.5) | <.001 | 101 (17–590) |

Discussion

This study confirms greater pain associated with IM compared with IV antibiotic administration in newborn sepsis evaluations. Despite this intuitive finding, parents preferred IM injections regardless of the antibiotic route their newborn received, perceiving more discomfort but less interference with breastfeeding and bonding. This finding has long-term implications because multiple painful procedures in neonates can lead to long-lasting pain sensitivity.12 We observed a positive slope of NIPS scores in the IM but not the IV group, suggesting sensitization to repeated needle injections. This is consistent with previous literature revealing that procedures as minor as heel punctures are associated with pain conditioning and elevated stress markers in neonates.8,13

Although in previous research, authors observed undertreatment of neonatal pain by health care providers,13 our data reveal that parents may prefer more painful treatments when other factors are considered. In parental surveys, parents agreed with the objective measures of greater pain, yet they displayed an unexpectedly strong preference for IM administration because of its subjective superiority over IV administration for bonding and breastfeeding, although LATCH scores did not corroborate this. This preference was observed despite socioeconomic factors in the IM site’s population that are generally associated with less satisfaction with health care, including non-English language preference, nonprivate insurance, and overall lower incomes, as estimated by United States census data by using patient zip codes.14–17 Although there is a move toward limiting antibiotic exposure in neonates at risk for early-onset sepsis, we believe that our results are relevant for neonates who do require antibiotics as well as relevant in other areas of care in which decisions on the route of medication delivery are influenced by assumptions about patient and parent preference.

Limitations of our study include the lack of formal assessment of confounders that can affect breastfeeding efficacy, such as previous experience, intent to breastfeed, milk letdown, nipple type, and lactation support. Additionally, we used validated measures, when able, but relied on an unvalidated parental survey because of the lack of such evaluations in previous literature. A larger study could include validation of our survey. In further research, authors could also evaluate differences after implementation of pain management strategies before needle injections and after an intervention to provide IV antibiotics at bedside.

Conclusions

Newborns experience greater pain and show evidence of pain sensitization with repeated IM versus IV antibiotic administration. Parents can recognize greater pain associated with IM antibiotics but may discount it in favor of perceived benefits to breastfeeding and bonding. These discordant views may have implications for long-term pain sensitivity in newborns as well as parental satisfaction relating to hospital care and may be taken into consideration by clinicians when selecting an antibiotic route for neonates undergoing sepsis evaluations.

Footnotes

Dr Patel conceptualized and designed the study, designed the data collection instruments, collected data at the 2 sites, and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Lin helped conceptualize the study, acquired and synthesized data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Guo helped conceptualize the study, analyzed the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Kulkarni helped design the study, acquired and synthesized data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant UL1TR001881. The funding source had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ; Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease–revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-10):1–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark RH, Bloom BT, Spitzer AR, Gerstmann DR. Empiric use of ampicillin and cefotaxime, compared with ampicillin and gentamicin, for neonates at risk for sepsis is associated with an increased risk of neonatal death. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan CS, John JF, Jr, Pai MS, Austin TL. Gentamicin vs cefotaxime for therapy of neonatal sepsis. Relationship to drug resistance. Am J Dis Child. 1985;139(11):1086–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao SC, Srinivasjois R, Hagan R, Ahmed M. One dose per day compared to multiple doses per day of gentamicin for treatment of suspected or proven sepsis in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11):CD005091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayani KC, Hatzopoulos FK, Frank AL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once-daily dosing of gentamicin in neonates. J Pediatr. 1997;131(1, pt 1):76–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Committee on Fetus and Newborn; Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Prevention and management of procedural pain in the neonate: an update. Pediatrics. 2016;137(2):e20154271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunau RE, Whitfield MF, Petrie-Thomas J, et al. Neonatal pain, parenting stress and interaction, in relation to cognitive and motor development at 8 and 18 months in preterm infants. Pain. 2009;143(1–2):138–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.France CR, Taddio A, Shah VS, Pagé MG, Katz J. Maternal family history of hypertension attenuates neonatal pain response. Pain. 2009;142(3):189–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taddio A, Shah V, Gilbert-MacLeod C, Katz J. Conditioning and hyperalgesia in newborns exposed to repeated heel lances. JAMA. 2002;288(7):857–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence J, Alcock D, McGrath P, Kay J, MacMurray SB, Dulberg C. The development of a tool to assess neonatal pain. Neonatal Netw. 1993;12(6):59–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen D, Wallace S, Kelsay P. LATCH: a breastfeeding charting system and documentation tool. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1994;23(1):27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermann C, Hohmeister J, Demirakça S, Zohsel K, Flor H. Long-term alteration of pain sensitivity in school-aged children with early pain experiences. Pain. 2006;125(3):278–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simons SH, van Dijk M, Anand KS, Roofthooft D, van Lingen RA, Tibboel D. Do we still hurt newborn babies? A prospective study of procedural pain and analgesia in neonates. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(11):1058–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quigley DD, Elliott MN, Hambarsoomian K, et al. Inpatient care experiences differ by preferred language within racial/ethnic groups. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(suppl 1):263–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weech-Maldonado R, Morales LS, Spritzer K, Elliott M, Hays RD. Racial and ethnic differences in parents’ assessments of pediatric care in Medicaid managed care. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(3):575–594 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haviland MG, Morales LS, Dial TH, Pincus HA. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and satisfaction with health care. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(4):195–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Census Bureau. Median income in the past 12 months (in 2017 inflation-adjusted dollars). Available at: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/results/tables?q=&tab=ACSST5Y2017.S1903. Accessed February 1, 2019