Abstract

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is characterized by chronic relapsing-remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. The chronic inflammatory process may predispose to atherosclerosis. The aim of the study was to assess the carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT) and its relation to subclinical atherosclerosis and to follow up cardiovascular complications in patients with UC.

Methods

83 patients with proven UC in remission were enrolled in the study. 42 age- and sex-matched healthy controls were taken. Patients with known risk factors for atherosclerosis were excluded from the study. Baseline blood investigations along with C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and fasting lipid profile were done. CIMT was measured using B-mode Doppler imaging study.

Results

The mean age of the UC patients was 37.06 ± 14.87 years. Left-sided colitis (45.8%) was the commonest type of presentation according to the extent of the disease. Mean CIMT (0.55 ± 0.17) was significantly higher in UC patients when compared to mean CIMT (0.46 ± 0.13) in the control group (p = 0.002). In Pearson correlation analysis, age, ESR, and CRP were positive and significantly correlated with CIMT. Multiple linear regression analysis (R<sup>2</sup> = 0.18, p = 0.0026) revealed that age and CRP were significant independent predictors of mean CIMT. On following up for 6 months, 4 patients with UC had complications in the form of venous thrombosis.

Conclusion

CIMT is a simple, noninvasive, reliable and objective auxiliary vascular parameter of structural alteration in UC patients.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Cardiovascular complications, Carotid intima-media thickness, Endothelial dysfunction, Ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is considered to be a disease of unknown etiology which develops due to an abnormal immune response resulting in chronic intestinal inflammation [1]. UC is characterized by chronic relapsing-remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. The chronic inflammatory process may predispose to atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is the main condition predisposing to the onset of cardiovascular (CV) events [2]. Atherothrombotic complications are an important cause of mortality and morbidity in many inflammatory diseases. Chronic inflammatory diseases and immune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) result in early and accelerated atherosclerosis even in the absence of other CV risk factors [3, 4, 5].

Atherosclerosis is characterized by vessel wall remodeling that occurs over the years. Obesity, aging, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia are the major factors responsible for endothelial dysfunction or progression of atherosclerosis. In recent studies, UC is considered as an important risk factor for the development of early atherosclerosis [6, 7]. Endothelial injury results in endothelial dysfunction and it is the initial step in the process of atherogenesis. In chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), there is reduced production of nitric oxide and decreased activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase causing impairment of endothelium-dependent vasodilatation [8, 9]. Intimal smooth muscle proliferation and atheroma formation results in an increment of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT). Ultrasonic measurement of CIMT can be used in the early diagnosis of atherosclerosis, risk classification, and evaluation of response to treatment [10, 11]. IBD-specific medication might have a role in the disease process and CIMT. Mesalamine acts by its anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. It possibly decreases the risk of thromboembolism by a reduction in platelet activation in the systemic circulation of IBD patients [12]. So, CIMT can be used as a tool for the detection of subclinical atherosclerosis in IBD patients [6, 7, 13].

The study is aimed to evaluate the utility of CIMT for the detection of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with UC who are in remission as well as for the prediction of CV complications.

Methods

Study Population

This was a cross-sectional observational study carried out at the Department of Gastroenterology, Government Medical College and Superspeciality Hospital, Nagpur, India, from June 2016 to December 2016. Institutional ethics committee approval was taken prior to starting the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Enrolment was done in a period of 6 months. UC patients were included based on clinical, radiologic, endoscopic and histological features with a minimum of 6 months' duration of the illness. The Mayo scoring system was used for the assessment of UC activity. According to the Montreal classification, the extent of the disease was classified into E1 (proctitis), E2 (left-sided colitis), and E3 (extensive colitis). Consecutive patients with UC who were in remission and on regular follow-up with the Gastroenterology Department were included. Remission was defined according to the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) consensus based on clinical parameters like stool frequency ≤3/day with no bleeding and no urgency.

Study Exclusion Criteria

Patients with known risk factors for atherosclerosis were excluded: (1) diabetes mellitus or on antidiabetic medications, (2) systemic hypertension (BP ≥140/90 mm Hg) or on antihypertensive medications, (3) coronary artery disease, (4) dyslipidemia (triglycerides >200 mg/dL and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >130 mg/dL), (5) chronic kidney disease, (6) age >60 years, (7) current or past smoker, (8) disease duration less than 6 months, and (9) those who are in a flare.

CIMT and Laboratory Tests

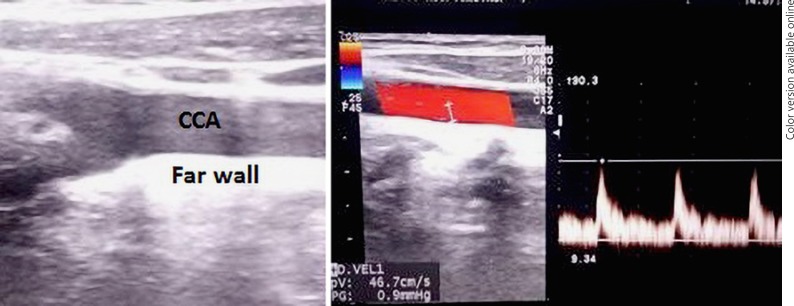

CIMT was measured with high-resolution B-mode ultrasonography using PHILIPS HD 11 XE with a 7.5-MHz linear array transducer. The carotid arteries were evaluated in supine position with the neck rotated 45° in a direction opposite to the site examined. The radiologist was blinded to both patients and controls. The CIMT was measured in end-diastole on the far wall at 5, 10, and 15 mm proximal to the carotid bifurcation over both the right and left common carotid arteries (CCA) (Fig. 1). The mean of three readings of each carotid artery was noted. The CIMT was defined as the distance from the leading edge of the first echogenic line to the leading edge of the second echogenic line [10]. Age- and sex-matched healthy controls were taken among those without risk factors for atherosclerosis. Blood pressure, body weight and height, and body mass index (BMI) were measured in all cases and the control group. Routine blood investigations along with C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and fasting lipid profile were performed after obtaining overnight fasting samples. All subjects were then followed up for 6 months to assess short-term clinical atherosclerotic complications, including myocardial infarction, stroke, acute mesenteric ischemia, and peripheral vascular disease.

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonographic view of the common carotid artery (CCA). CIMT measurements done in the far wall of the CCA.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical software, namely SPSS 18.0, and R environment ver. 3.2.2 were used for the analysis of the data. Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were carried out. Results of continuous measurements were presented as mean ± standard deviation (min–max) and results of categorical measurements were presented as number (%). Significance was assessed at the 5% level of significance. The Student t test (two-tailed, independent) was used to find the significance of study parameters on a continuous scale between two groups (intergroup analysis) on metric parameters. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between study variables was taken to find the degree of relationship. The χ2 or the Fisher exact test were used to find the significance of study parameters on a categorical scale between two or more groups. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed with age, BMI, hemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), platelet, ESR, CRP, and total protein to find out which variable is the most significant independent predictor of CIMT.

Results

Demographic Characteristics and Laboratory Variables of UC Patients and Controls

A total of 83 patients with UC were enrolled. Out of them, 47 (56.6%) were males and 36 (43.4%) were females. The male-to-female ratio was 1.3:1. There were 42 healthy subjects in the control group, including 25 (59.5%) males and 17 (40.5%) females with a male-to-female ratio of 1.47:1. The mean ages of UC patients and the control group were 37.06 ± 14.87 years and 37.17 ± 11.96 years, respectively. The mean duration of the disease was 2.59 ± 1.95 years. The commonest type of presentation in UC patients was left-sided colitis (E2) (n = 38, 45.8%) followed by extensive colitis (E3) (n = 36, 43.4%) and the least common type was proctitis (E1) (n = 9, 10.8%). The mean BMI of the control group (23.61 ± 2.92) was significantly higher than that in the UC group (18.82 ± 3.77; p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| Variables | UC patients (n = 83) | Control (n = 42) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 37.06±14.87 | 37.17±11.96 | 0.968 |

| Gender, M:F | 1.3:1 | 1.47:1 | 0.757 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 18.82±3.77 | 23.61±2.92 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 121.95±10.23 | 123.43±10.95 | 0.458 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 71.95±8.35 | 71.38±8.16 | 0.717 |

All characteristics are given as mean ± standard deviation unless indicated otherwise.

ESR and C-reactive protein CRP were significantly higher in the UC group (p < 0.05). Anemia was more prevalent in UC patients with lower hemoglobin and MCV values, which were statistically significant compared to controls (p < 0.001). The baseline Mayo score of UC patients was 1.84 ± 0.56. Most of the UC patients were on mesalamine alone (n = 66, 79.5%) followed by mesalamine with azathioprine (n = 17, 20.5%). It was not found to be statistically significant.

Comparison between UC patients and controls had not revealed significant differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total bilirubin, albumin, AST, ALT, creatinine, total cholesterol, triglyceride level, low-density lipoprotein, very-low-density lipoprotein, and high-density lipoprotein levels and fasting blood sugar levels (Table 2).

Table 2.

Laboratory characteristics of the study population

| Variables | UC patients (n = 83) | Controls (n = 42) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 9.86±2.38 | 11.92±1.72 | <0.001 |

| Platelet, 103/mm3 | 3.43±1.33 | 2.76±0.78 | 0.003 |

| MCV, fL | 74.75±10.63 | 82.67±5.82 | <0.001 |

| ESR, mm/h | 31.41±15.15 | 9.45±4.19 | <0.001 |

| Total protein, g/dL | 6.42±0.74 | 6.71±0.56 | 0.025 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.29±0.56 | 3.36±0.59 | 0.475 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.91±0.42 | 0.98±0.55 | 0.432 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 4.75±3.35 | 3.58±2.19 | 0.04 |

| Fasting blood sugar, mg/dL | 84.82±17.54 | 85.71±12.44 | 0.768 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 136.63±25.51 | 135.57±22.24 | 0.820 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 99.42±23.76 | 102.64±24.06 | 0.477 |

| Low-density lipoprotein, mg/dL | 91.6±22.67 | 91.08±16.99 | 0.897 |

| High-density lipoprotein, mg/dL | 39.71±3.85 | 41.024±3.83 | 0.09 |

All characteristics are given as mean ± standard deviation.

Carotid Intima-Media Thickness

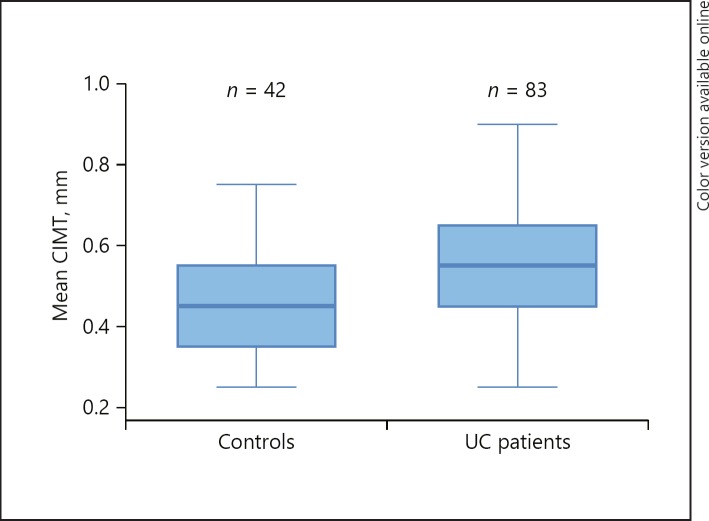

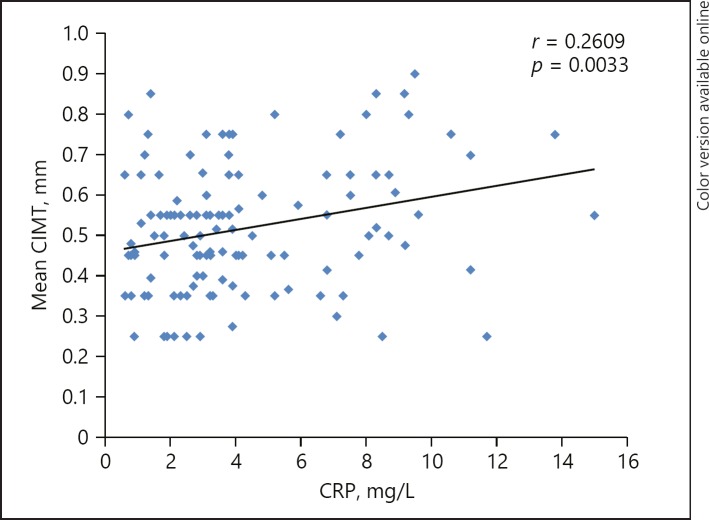

The mean CIMT of the right CCA and left CCA was significantly higher in the UC group. The mean CIMT (0.55 ± 0.17) and maximum CIMT (0.61 ± 0.17) values were statistically significant in the UC patients when compared to the mean (0.46 ± 0.13) and maximum CIMT (0.51 ± 0.14) in the control group (p = 0.002, 0.003, respectively) (Table 3; Fig. 2). On comparing CIMT with the extent of the disease, namely, proctitis, left-sided colitis, and extensive colitis, no statistically significant association was seen. In Pearson correlation analysis, age, ESR, and CRP were positive and significantly correlated with mean CIMT among UC patients (Table 4; Fig. 3). Multiple linear regression analysis (R2 = 0.18, p = 0.0026) revealed that age and CRP were significant independent predictors of mean CIMT (Table 5).

Table 3.

CIMT values in the study population

| UC patients (n = 83) | Control(n = 42) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIMT right, mm | 0.56±0.17 | 0.49±0.14 | 0.025 |

| CIMT left, mm | 0.54±0.18 | 0.42±0.14 | <0.001 |

| CIMT mean, mm | 0.55±0.17 | 0.46±0.13 | 0.002 |

| CIMT maximum, mm | 0.61±0.17 | 0.51±0.14 | 0.003 |

All characteristics are given as mean ± standard deviation.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of mean CIMT in UC patients and controls.

Table 4.

Pearson correlation between mean CIMT and UC patients

| Pair | r value | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Mean CIMT versus age (years) | 0.23 | 0.009 |

| Mean CIMT versus BMI (kg/m2) | −0.095 | 0.28 |

| Mean CIMT versus hemoglobin (g/dL) | −0.058 | 0.51 |

| Mean CIMT versus MCV (fL) | 0.035 | 0.69 |

| Mean CIMT versus CRP (mg/L) | 0.26 | 0.003 |

| Mean CIMT versus ESR (mm/h) | 0.22 | 0.014 |

| Mean CIMT versus platelet (103/mm3) | −0.06 | 0.47 |

| Mean CIMT versus total protein (g/dL) | −0.10 | 0.23 |

Fig. 3.

Positive correlation between mean CIMT and CRP.

Table 5.

Multiple linear regression analysis of variables associated with CIMT

| Predictors of CIMT | Regression coefficient β | Standard error | t value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.002 | 0.001 | 2.43 | 0.017 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −0.007 | 0.004 | −1.64 | 0.104 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.29 | 0.772 |

| MCV (fL) | 0.003 | 0.001 | 1.83 | 0.07 |

| Platelet (103/mm3) | −0.012 | 0.012 | −0.95 | 0.344 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | −0.008 | 0.02 | −0.42 | 0.679 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 0.001 | 0.001 | 1.46 | 0.147 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 0.011 | 0.004 | 2.33 | 0.021 |

During the follow-up period of 6 months, 2 patients had deep venous thrombosis of the lower limb, 1 each from the left-sided colitis (E2) and extensive colitis (E3) group. Two patients from the extensive colitis (E3) group had complications in the form of hepatic vein thrombosis presented as acute Budd-Chiari syndrome and another had inferior vena cava thrombosis. However, no one from the control group developed any CV complications on follow-up. This was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.299).

Discussion

UC is a chronic disease of unknown etiology which may also have extra intestinal manifestations [14]. In etiopathogenesis of UC, inflammation has a significant role. This chronic low-grade inflammation may cause early development of atherosclerosis in UC. Dagli et al. [7] suggested that there is evolving evidence that IBD is an independent factor for the development of atherosclerosis. Several inflammatory and immunological diseases, such as RA and SLE, have an association between arterial stiffness and early atherosclerosis, which results in atherothrombotic complications [3, 15]. Increased coronary and cerebral artery atherosclerosis represent one of the most important causes of mortality and morbidity in RA and SLE patients [16]. IBD is an inflammatory state that causes release of different pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor, etc.), which results in endothelial dysfunction [8]. This immune dysregulation is the predominant factor causing intestinal injury. Other factors like microvascular dysfunction with impairment in vasodilatation and increased adhesion molecule expression at microvascular levels may have a role [17]. Subsequently, it culminates into reduced perfusion, impaired wound healing, and maintenance of chronic inflammation in patients with UC [9].

Both IBD and atherosclerosis share a potential mediator, CD40/CD40 ligand (CD40L) dyad. Danese et al. [18] demonstrated that platelets trigger CD40L-dependent inflammatory response in the intestinal microvasculature of patients with IBD and thus induce microthrombosis. Santilli et al. [19] showed that the CD40/CD40L dyad has an association with vascular diseases due to evidence of increased inflammation, thrombosis, and atherosclerosis. These inflammatory process results in granulomatous or lymphocytic inflammation with vascular injury, focal arteritis, and fibrin deposition in the chronically inflamed gut mucosa [20]. In patients with UC, the therapeutic use of unfractionated heparin as well as low-molecular-weight heparin gives an indirect evidence of the vascular contribution in the pathogenesis of IBD [21].

Atherosclerosis is a complex process which is initiated by endothelial dysfunction. Following this, arterial stiffness sets in due to smooth muscle cell proliferation. Consecutively, structural alterations occur in the vessel wall and plaque formation occurs. For these abnormalities, noninvasive vascular parameters are used. Flow-mediated dilatation is used for endothelial dysfunction and carotid femoral pulse wave velocity as a marker of arterial stiffness [22]. CIMT is a vascular parameter of structural alterations in intima and media in early atherosclerosis [23].

In our study, we have utilized CIMT for the detection of early atherosclerosis in UC patients. Chronic inflammation alone or along with risk factors of atherosclerosis results in an increment in CIMT. This might also result in a hypercoagulable state. In various studies performed on patients with diabetes mellitus, familial hypercholesterolemia, and uremia as well as in RA and SLE, CIMT was found to be best validated by ultrasound Doppler measurement of early vascular disease [24]. Lorenz et al. [25] showed that in elderly, CIMT is useful in the prediction of risk of CV events and for every 0.1-mm increment of CIMT corresponding to 10–15 and 13–18% increased risk for acute myocardial infarction and stroke, respectively.

In our study, CIMT was significantly higher in UC patients compared to healthy control groups. This might be due to chronic low-grade inflammation during remission periods and bouts of increased inflammatory activity during the flare. Our findings were consistent with a study done by Papa et al. [26] who demonstrated increased CIMT in IBD patients, predominantly in patients of UC. Dagli et al. [7] in 2010 suggested that IBD is a risk factor for atherosclerosis and CIMT can accurately predict atherosclerosis. However, Maharshak et al. [27] found no difference in CIMT in the IBD population and the control group and they proposed there is a questionable benefit of performing CIMT. On comparing CIMT with disease extent, there was not any significant association seen between them. It could be possibly due to a differing in grades of inflammation and this variation is not according to the extent of the disease. Similar results were shown in another study, with no significant association seen between disease extent and CIMT [28]. Also, a recent metanalysis by Wu et al. [29] showed that there was a significantly higher CIMT in IBD patients. They also had significantly lower flow-mediated dilatation and increased carotid femoral pulse wave velocity. CIMT and carotid plaques have importance in the reflection of CV risk. It supports the clinical utility of these markers in the evaluation of subclinical atherosclerosis and an elevated CV burden in IBD.

We analyzed clinical and laboratory variables like age, BMI, hemoglobin, MCV, platelet, ESR, CRP, and total protein for the determination of a significant independent predictor of CIMT. On analysis, BMI, ESR, hemoglobin, MCV, and platelet were statistically significant compared to the control group. Pearson correlation showed positive correlation with age, ESR, and CRP. Multiple linear regression analysis revealed that age and CRP were independent variables associated with mean CIMT to assess the subclinical atherosclerotic burden in UC. ESR and CRP are markers of inflammation and even though during periods of remission, due to the underlying chronic active disease process, their levels are raised. Similarly, progression of age is significantly associated with arterial stiffness. Raised levels of CRP are associated with complement activation and it imparts overexpression of adhesion molecules and rupture of the atherosclerotic plaque [30]. On the contrary, Principi et al. [31] found no difference in ESR and CRP between IBD and the control group. Also, CRP and ESR did not correlate with CIMT in IBD patients who were in remission.

Due to the underlying progressive inflammation that occurs in atherosclerosis, it results in fatal vascular complications [32]. Increased incidence of a CV event like ischemic heart disease have been reported in IBD [33]. We followed up UC patients and a control group for 6 months to assess short-term CV complications. In the UC group, 4 patients developed venous thrombosis during follow-up. Most of them were from an extensive colitis group. However, this complication on comparison with controls was not found to be significant (p = 0.299). So, extensive inflammation of the colon might play a role in this. None of the UC patients and the control group developed arterial thromboembolic events such as stroke and myocardial infarction. This could be explained on the basis that atherosclerosis is a slow, progressive mural process which is in its later course often accompanied by failure of vascular remodeling. This results in significant lumen compromise and subsequently fatal vascular thrombotic complications. In contrast to that, venous thrombosis has an acute presentation. Similarly, a retrospective cohort study done by Ha et al. [34] found that there is no increased risk of arterial thrombotic events including myocardial infarction and transient ischemic attack. Venous thromboembolic events are more common in IBD patients compared to an arterial thromboembolic event. In another meta-analysis, it was shown that there is no increased CV mortality observed in patients with IBD [35]. Even though UC is a potential inflammatory state, the risk of atherosclerosis-related morbidity and mortality is less. It could be explained due to reduced visceral obesity in IBD patients, as leptin which has pro-inflammatory action synthesized in adipose tissue [36].

The utility of CIMT for the evaluation of early atherosclerosis and its complications is debatable.

A limitation of our study is that we had included patients in remission, so a single measurement of CIMT might not be able to give information about generalized activity of disease. Short duration of follow-up for CV complications is another limitation. Future studies with long-term follow-up to exactly predict CV complications are needed.

In conclusion, chronic low-grade inflammation in UC causes endothelial dysfunction and early atherosclerosis even in the phase of remission. This increased subclinical atherosclerotic burden can be measured by CIMT. CIMT is a simple, noninvasive, reliable and objective auxiliary vascular parameter of structural alteration in UC.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional ethics committee approval was taken prior to starting of study. Informed consent was obtained from the study population.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

Grants and financial support: nil.

Author Contributions

Harit Goverdhan Kothari: enrolment of study population, collection of data and formulation of manuscript.

Sudhir Jagdishprasad Gupta: reviewing and editing of manuscript, supervision of study.

Nitin Rangrao Gaikwad: reviewing and editing of manuscript.

References

- 1.Hatoum OA, Binion DG, Contribution to Pathogenesis and Clinical Pathology The vasculature and inflammatory bowel disease: contribution to pathogenesis and clinical pathology. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005 Mar;11((3)):304–13. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000160772.78951.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pathan F, Negishi K. Prediction of cardiovascular outcomes by imaging coronary atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016 Aug;6((4)):322–39. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2015.12.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Doornum S, McColl G, Wicks IP. Accelerated atherosclerosis: an extraarticular feature of rheumatoid arthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Apr;46((4)):862–73. doi: 10.1002/art.10089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selzer F, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Fitzgerald SG, Pratt JE, Tracy RP, Kuller LH, et al. Comparison of risk factors for vascular disease in the carotid artery and aorta in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Jan;50((1)):151–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK, Leducq Transatlantic Network on Atherothrombosis Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Dec;54((23)):2129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papa A, Danese S, Urgesi R, Grillo A, Guglielmo S, Roberto I, et al. Early atherosclerosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2006 Jan-Feb;10((1)):7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dagli N, Poyrazoglu OK, Dagli AF, Sahbaz F, Karaca I, Kobat MA, et al. Is inflammatory bowel disease a risk factor for early atherosclerosis? Angiology. 2010 Feb;61((2)):198–204. doi: 10.1177/0003319709333869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Principi M, Mastrolonardo M, Scicchitano P, Gesualdo M, Sassara M, Guida P, et al. Endothelial function and cardiovascular risk in active inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohn's Colitis. 2013 Nov;7((10)):e427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatoum OA, Binion DG, Otterson MF, Gutterman DD. Acquired microvascular dysfunction in inflammatory bowel disease: loss of nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation. Gastroenterology. 2003 Jul;125((1)):58–69. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, et al. American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force; Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008 Feb;21((2)):93–111. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukherjee D, Yadav JS. Carotid artery intimal-medial thickness: indicator of atherosclerotic burden and response to risk factor modification. Am Heart J. 2002 Nov;144((5)):753–9. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.124865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carty E, MacEy M, Rampton DS. Inhibition of platelet activation by 5-aminosalicylic acid in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000 Sep;14((9)):1169–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanoli L, Cannavò M, Rastelli S, Di Pino L, Monte I, Di Gangi M, et al. Arterial stiffness is increased in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Hypertens. 2012 Sep;30((9)):1775–81. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283568abd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothfuss KS, Stange EF, Herrlinger KR. Extraintestinal manifestations and complications in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006 Aug;12((30)):4819–31. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i30.4819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salmon JE, Roman MJ. Subclinical atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 2008 Oct;121((10) Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ward MM. Premature morbidity from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Feb;42((2)):338–46. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199902)42:2<338::AID-ANR17>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laroux FS, Grisham MB. Immunological basis of inflammatory bowel disease: role of the microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2001 Oct;8((5)):283–301. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danese S, de la Motte C, Sturm A, Vogel JD, West GA, Strong SA, et al. Platelets trigger a CD40-dependent inflammatory response in the microvasculature of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterology. 2003 May;124((5)):1249–64. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00289-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santilli F, Basili S, Ferroni P, Davì G. CD40/CD40L system and vascular disease. Intern Emerg Med. 2007 Dec;2((4)):256–68. doi: 10.1007/s11739-007-0076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhillon AP, Anthony A, Sim R, Wakefield AJ, Sankey EA, Hudson M, et al. Mucosal capillary thrombi in rectal biopsies. Histopathology. 1992 Aug;21((2)):127–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1992.tb00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papa A, Danese S, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Review article: potential therapeutic applications and mechanisms of action of heparin in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000 Nov;14((11)):1403–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00860.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozturk K, Guler AK, Cakir M, Ozen A, Demirci H, Turker T, et al. Pulse wave velocity, intima media thickness, and flow-mediated dilatation in patients with normotensive normoglycemic inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015 Jun;21((6)):1314–20. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Touboul PJ. Clinical impact of intima media measurement. Eur J Ultrasound. 2002 Nov;16((1-2)):105–13. doi: 10.1016/s0929-8266(02)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumeda Y, Inaba M, Goto H, Nagata M, Henmi Y, Furumitsu Y, et al. Increased thickness of the arterial intima-media detected by ultrasonography in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Jun;46((6)):1489–97. doi: 10.1002/art.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2007 Jan;115((4)):459–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Papa A, Santoliquido A, Danese S, Covino M, Di Campli C, Urgesi R, et al. Increased carotid intima-media thickness in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005 Nov;22((9)):839–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maharshak N, Arbel Y, Bornstein NM, Gal-Oz A, Gur AY, Shapira I, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is not associated with increased intimal media thickening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 May;102((5)):1050–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theocharidou E, Gossios TD, Griva T, Giouleme O, Douma S, Athyros VG, et al. Is there an association between inflammatory bowel diseases and carotid intima-media thickness? Preliminary data. Angiology. 2014 Jul;65((6)):543–50. doi: 10.1177/0003319713489876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu GC, Leng RX, Lu Q, Fan YG, Wang DG, Ye DQ. Subclinical Atherosclerosis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Angiology. 2017 May;68((5)):447–61. doi: 10.1177/0003319716652031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molenaar ET, Voskuyl AE, Familian A, van Mierlo GJ, Dijkmans BA, Hack CE. Complement activation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis mediated in part by C-reactive protein. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 May;44((5)):997–1002. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<997::AID-ANR178>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Principi M, Montenegro L, Losurdo G, Zito A, Devito F, Bulzis G, et al. Endothelial function and cardiovascular risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission phase. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51((2)):253–5. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1070901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002 Dec;420((6917)):868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yarur AJ, Deshpande AR, Pechman DM, Tamariz L, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011 Apr;106((4)):741–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ha C, Magowan S, Accortt NA, Chen J, Stone CD. Risk of arterial thrombotic events in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jun;104((6)):1445–51. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorn SD, Sandler RS. Inflammatory bowel disease is not a risk factor for cardiovascular disease mortality: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Mar;102((3)):662–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan F, Galvin A, Fang L, White DA, Moore XL, Sparrow M, et al. Comparison of inflammation, arterial stiffness and traditional cardiovascular risk factors between rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 2014 Oct;11((1)):29. doi: 10.1186/s12950-014-0029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]