Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests social media use is associated with mental health in young people but underlying processes are not well understood. This paper i) assesses whether social media use is associated with adolescents' depressive symptoms, and ii) investigates multiple potential explanatory pathways via online harassment, sleep, self-esteem and body image.

Methods

We used population based data from the UK Millennium Cohort Study on 10,904 14 year olds. Multivariate regression and path models were used to examine associations between social media use and depressive symptoms.

Findings

The magnitude of association between social media use and depressive symptoms was larger for girls than for boys. Compared with 1–3 h of daily use: 3 to < 5 h 26% increase in scores vs 21%; ≥ 5 h 50% vs 35% for girls and boys respectively. Greater social media use related to online harassment, poor sleep, low self-esteem and poor body image; in turn these related to higher depressive symptom scores. Multiple potential intervening pathways were apparent, for example: greater hours social media use related to body weight dissatisfaction (≥ 5 h 31% more likely to be dissatisfied), which in turn linked to depressive symptom scores directly (body dissatisfaction 15% higher depressive symptom scores) and indirectly via self-esteem.

Interpretation

Our findings highlight the potential pitfalls of lengthy social media use for young people's mental health. Findings are highly relevant for the development of guidelines for the safe use of social media and calls on industry to more tightly regulate hours of social media use.

Funding

Economic and Social Research Council.

Keywords: Social media, Mental health, Adolescence, Sleep, Body image, Self-esteem, Online harassment

Research in context

Evidence before this study

We systematically reviewed MEDLINE for studies about social media use and mental health in adolescents published in English between database inception and May 30, 2018, using the following search terms: “social media”, “adolescent”, “cyberbullying”, “mental health”, “self-esteem”, “sleep” and “body image”. Studies suggest social media use is associated with mental health in young people; several identified plausible potential explanations for links between social media use and mental health, include experiences of online harassment, effects on sleep, self-esteem and body image. To our knowledge no prior studies have examined all these potential explanations simultaneously.

Added value of this study

Using large scale data generalisable to the wider population on more than 10,000 14 year olds, we examined multiple pathways simultaneously finding: for girls across the range of daily social media use, from none to 5 or more hours, a strong stepwise increase in depressive symptom scores and the proportion with clinically relevant symptoms; for boys, higher depressive symptom scores were seen among those reporting 3 or more hours daily use; for boys and girls, greater social media use related to poor sleep, poor body image, experience of online harassment and low self-esteem, all of which in turn related directly to depressive symptoms. Multiple intervening pathways between social media use and depressive symptoms were apparent. The most important pathways were via poor sleep and online harassment. For example: more social media use linked to poor sleep which in turn was related to depressive symptoms; experiencing online harassment was linked to poor sleep, poor body image and low self-esteem; and that girls and boys with poor body image were more likely to have low self-esteem.

Implications of all the available evidence

Poor sleep, online harassment, poor body image and low self-esteem appear important pathways via which social media use is associated with depressive symptoms in young people. Findings are highly relevant for the development of guidelines for the safe use of social media and calls on industry to more tightly regulate hours of social media use.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Youth mental health is a major public health concern which poses substantial societal and economic burdens globally [1], [2]. Adolescence is a period of vulnerability for the development of depression [3] and young people with mental health problems are at higher risk of poor mental health throughout their lives [4]. Therefore, intervening early could have long-term knock on benefits for population health. Social media use, a relatively recent phenomena, has become the primary form of communication for young people in the UK and elsewhere [5], [6]. Undoubtedly, using social media can be beneficial including as a source of social support and knowledge acquisition, however, a mounting body of evidence suggests associations with poor mental health among young people [7], [8]. Moreover, a recent report using longitudinal data suggests that girls may be more affected than boys [9]. Amid the public debate on the pros and cons of social media use taking place in the UK and elsewhere, the British Secretary of State for Health has joined recent calls for social media organisations to regulate use more tightly [10], [11] and an investigation by the Chief Medical Officer into the links between social media use and young people's mental health is underway.

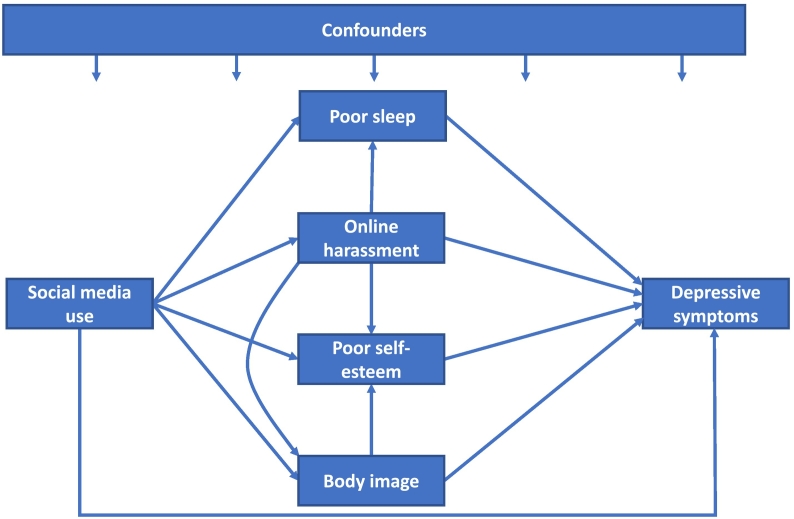

Numerous plausible potential intervening pathways relate young people's mental health to the amount of time they spend on social networking sites, and the ways in which they engage and interact online. Widely researched are pathways via experiences of online harassment, as victim and/or perpetrator, which have the potential to impact on young people's mental health due to the ease of sharing of materials that damage reputations and relationships [12], [13], [14]. It is commonplace for young people to sleep in close proximity to their phones [15] and sleep has been shown to be linked to mental health [16], [17]. Social media use could impact on young people's sleep in multiple ways, for instance spending a long time on social media might lead to reduced sleep duration, whilst incoming alerts in the night and fear of missing out on new content could cause sleep disruptions [18], [19], [20]. Screen exposure before bedtime and the consequent impact of this on melatonin production and the circadian rhythm are also possible mechanisms [21]. Sleep quality and quantity could also be affected by levels of anxiety and worry resulting from experiences of online harassment. Young people are particularly vulnerable to the development of low self-esteem [22] and this could be exacerbated by online experiences including receipt of negative feedback and negative social comparisons [23], [24]. The abundance of manipulated images of idealised ‘beauty’ online are linked to individual perceptions of body image and self-esteem which in turn are associated with poor mental health [25], [26]. It is also important to acknowledge that a cyclical relationship between social media use and mental health could be at play, whereby young people experiencing poor mental health might be more likely to use social media for extended periods of time. However, to our knowledge, prior research has not examined all these potential explanatory pathways between social media use and mental health at the same time, and in an attempt to improve understanding of the mechanisms at play, in this paper we simultaneously examine multiple potential pathways between social media use and a marker of young people's mental health. We hypothesise, net of prior mental health, that: i) the relationship between social media use and depressive symptoms would be partially mediated through poor sleep, online harassment, poor self-esteem and body image; ii) the association of online harassment with depressive symptoms would be partially mediated by poorer sleep, poor body image and poor self-esteem; and iii) the poor body image relationship with depressive symptoms would be partially mediated by poor self-esteem (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Hypothesised pathways between social media use and depressive symptoms in young people.

We use data from a large representative population-based cohort study of adolescents, the Millennium Cohort Study. Given potential gender differences in associations, we explore among girls and boys, the following objectives: 1. To assess whether social media use is associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents, and 2. To investigate potential explanatory pathways for observed associations – via online harassment, sleep, self-esteem and body image.

2. Methods

The Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) is a UK nationally representative prospective cohort study of children born into 19,244 families between September 2000 and January 2002 (http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=1806&itemtype=document). Participating families in receipt of Child Benefit (98% of the population at the time of sampling) were selected from a random sample of electoral wards with a stratified sampling design to ensure adequate representation of all four UK countries, disadvantaged and ethnically diverse areas. The first sweep of data was collected when cohort members were around 9 months and the subsequent five sweeps of data were collected at ages 3, 5, 7, 11 and 14 years. At age 14 cohort members and their carers were interviewed during home visits. Cohort members self-completed computer assisted questionnaires in private including items about social media use, mental health, online harassment, sleep, self-esteem and body image. Carers (the majority of whom were cohort members' parents and for ease throughout are referred to as parents) answered questions about socioeconomic circumstances and cohort member's social and emotional difficulties at age 11. Interview data were available for 61% of families when cohort members were aged 14 [27].

2.1. Depressive Symptoms

Participants completed the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire – short version (SMFQ) from which a summed score was created [28]. The SMFQ comprises 13 items on affective symptoms in the last 2 weeks (see Box 1). In supplementary analysis we derived a binary variable to capture the presence of clinically relevant symptoms using a cut point of ≥ 12 [29].

Box 1. Measures used in analysis.

| Measure | Questionnaire items | Analysis variable |

|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | Participants completed the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire – short version (SMFQ) from which a summed score was created. The SMFQ comprises 13 items on affective symptoms in the last 2 weeks as follows: felt miserable or unhappy; didn't enjoy anything at all; so tired just sat around and did nothing; was very restless; felt I was no good anymore; cried a lot; found it hard to think properly or concentrate; hated myself; was a bad person; felt lonely; thought nobody really loved me; thought I could never be as good as other kids; did everything wrong. | Log transformed continuous variable used in modelling; generated dichotomous variable indicating clinically relevant symptoms (cut point ≥ 12) |

| Social media usea | Respondents were asked “On a normal week day during term time, how many hours do you spend on social networking or messaging sites or Apps on the internet such as Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp?” (response categories: None, less than half an hour, half an hour to less than 1 h, 1 h to less than 2 h, 2 h to less than 3 h, 3 h to less than 5 h, 5 h to less than 7 h, 7 h or more). | Categories were collapsed to generate a variable as follows: none, < 1 h, 1 to < 3 h, 3 to < 5 h, ≥ 5 h. |

| Online harassmentb | “How often have other children sent you unwanted or nasty emails, texts or messages or posted something nasty about you on a website?”; “How often have you sent unwanted or nasty emails, texts or messages or posted something nasty about other children on a website?” response categories for both questions: most days; about once a week; about once a month; every few months; less often; never |

Combined responses capturing any involvement as victim and/or perpetrator to generate a variable with 4 categories: no involvement; victim; perpetrator; perpetrator-victim. (Adapted from Fahy et al[12]) |

| Sleep duration | “About what time do you usually go to sleep on a school night?” “About what time do you usually wake up in the morning on a school day?”. | A 4-category variable was generated: 7 h or less, 8, 9, 10 + h |

| Sleep latency | A sleep latency variable was constructed from answers to the question “During the last four weeks, how long did it usually take for you to fall asleep?” | A 3-category variable was created: 0–30, 30–60, > 60mins. |

| Sleep disruption | Disruptions to sleep were assessed using the question “During the last four weeks, how often did you awaken during your sleep time and have trouble falling back to sleep again?” | A 4-category variable was created: all/most of the time; often; a little of the time; and none of the time. |

| Self-esteem c | Self-esteem was assessed using the items on self-satisfaction from the Rosenberg scale: having good qualities; able to do things similar to others; person of value; and feel good about oneself. | A dichotomised variable (low vs normal/high) derived from the sum of the items, scores ≥ 7 (i.e. the top 20% of the distribution) indicate low self-esteem. |

| Happiness with appearance | Happiness with appearance was measured, as follows: “On a scale of 1 to 7 where ‘1’ means completely happy and ‘7’ means not at all happy, how do you feel about the way you look?” | A log transformed continuous variable was used in modelling. A dichotomised variable (1–6 vs 7) was used for display purposes in Table 1, Table 2. |

| Body weight satisfaction | Body weight satisfaction was assessed from 3 items: “Which of these do you think you are?” (underweight, about the right weight, slightly overweight, very overweight), “Have you ever exercised to lose weight or to avoid gaining weight?”, “Have you ever eaten less food, fewer calories, or foods low in fat to lose weight or to avoid gaining weight?”. | Responses other than ‘about the right weight’ or affirmative to exercising or eating to lose or maintain weight were combined to generate a body satisfaction variable (satisfied vs dissatisfied). |

Alternative specifications that assumed a continuous normal distribution were rejected due to heteroscedasticity.

Treating the online harassment victim and -perpetrator variables as ordinal and testing for an interaction between the two variables resulted in an unwieldy number of parameters. Assuming the variables to be continuous was not tenable due to their distributional patterns.

The Rosenberg Scale had a distinctly non-normal distribution for which no transformation was satisfactory. Regression models using the raw scale show significant heteroscedasticity.

Alt-text: Box 1

2.2. Social media use

Respondents were asked about their average hours of social media use on a weekday (for details of response categories see Box 1). The item used was developed by the Millennium Cohort Study team and is similar to items used in other large surveys including the UK Household Longitudinal Study [9] and Ofcom [5]. The social media measure was not used as a continuous variable due to heteroscedasticity. We generated a variable as follows: none, < 1 h, 1 to < 3 h, 3 to < 5 h, ≥ 5 h. 1–3 h was the most prevalent category and is used as the reference category in multivariate modelling.

Questionnaire items on online harassment, sleep, self-esteem (Rosenberg scale [30]) and body image are detailed in Box 1.

The online harassment measure was treated as a categorical variable due to distributional patterns. A binary variable for self-esteem was used because of non-normal distribution for which no transformation was satisfactory, and the raw data showed significant heteroscedasticity.

2.3. Confounders

In line with prior research [9] we controlled for the following confounders in our analyses: family income – equivalised fifths; family structure (two vs one parent); and age in years. In an attempt to take account of the potentially cyclical association between social media use and depressed mood we controlled for internalising symptoms (continuous scale, derived from the parent completed Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire) [31] from earlier in adolescence when participants were aged 11.

2.4. Study Sample

We analysed data on singleton-born cohort members for whom data on depressive symptoms were available. The analytical sample was 10,904 after multiply imputing missing values on explanatory factors due to item non-response, with the amount of missing covariate data ranging from 0% to 8%. We employed multiple imputation which accounts for uncertainty about missing values by imputing several values for each missing data point [32]. We imputed 20 data sets, and report consolidated results from all imputations using Rubin's combination rules [33]. Results from the imputed analyses did not vary substantively from the analyses using listwise deletion (analysis not shown).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To examine whether and by how much associations between social media use and depressive symptoms were explained by markers of online harassment, sleep, self-esteem and body image we ran multivariable linear regression models, adding and removing variables in separate blocks of adjustment, as follows:

Model 0 – social media use plus confounders (family income, family structure, age, internalising symptoms at age 11)

Model 1 – M0 plus online harassment

Model 2 – M0 plus sleep quantity and quality (sleep hours, latency and disruption)

Model 3 – M0 plus self-esteem

Model 4 – M0 plus body image (happy with appearance and body weight satisfaction)

The potential a priori moderating effect of gender on the social media use and depressive symptoms relationship was tested for (using Wald t-tests) by adding in a gender by social media use interaction term to Model 0 (p < 0.05). The regression model findings are therefore presented for girls and boys separately. Wald tests assessed the a priori role of online harassment, sleep, self-esteem and body image as mediators between social media use and log depressive symptoms, by showing the significance of social media use before (Model 0) and after their introduction (Models 1–4).

In supplementary analysis, to assess consistency of findings, we ran logistic regression models using a binary indicator for clinically relevant symptoms.

Path models were then estimated to quantify the hypothesised explanatory pathways between social media use and mental health (see Fig. 1). A first model allowed all paths to differ by gender. Wald tests then assessed the statistical significance of any differences, after Bonferroni adjustment to account for the 75 tests. In the second model, all non-significantly different paths were constrained to be equal across gender.

The path models were estimated using the generalised structural equation model, GSEM command in Stata, which allows for the continuous, binary, categorical and ordered measures to be modelled using linear, logistic, multinomial and ordinal logistic specifications, respectively.

All analyses were carried out using Stata version 15.1 (Stata Corp). Survey weights were applied throughout to take account of the unequal probability of being sampled.

3. Role of the Funding Source

The study was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/R008930/1). The funder had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all intermediate outputs, with the study statisticians (AZ and AS) having access to the full study datasets. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

4. Results

The average age of participants was 14.3 (SD 0.34) years. Girls reported more hours of social media use than did boys. Over two fifths of girls used social media for 3 or more hours per day compared with one fifth of boys (43.1% vs 21.9% respectively), and only 4% of girls reported not using social media compared to 10% of boys (Table 1). Compared with boys, girls were more likely to be involved in online harassment as a victim or perpetrator (38.7% vs 25.1% respectively). Girls were more likely to have low self-esteem (12.8% vs 8.9%), to have body weight dissatisfaction (78.2% vs 68.3%) and to be unhappy with their appearance (15.4% vs 11.8%). Girls were more likely to report fewer hours of sleep compared with boys (< 7 h 13.4% vs 10.8%) and to report experiencing disrupted sleep often (27.6% vs 20.2%) or most of the time (12.7% vs 7.4%) but were similar in reporting how long it took them to fall asleep (Table 1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of social media use by potential explanatory factors and confounders.

| Girls (n = 5496) |

Boys (n = 5408) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | None | < 1 h | 1 to < 3 h | 3 to < 5 h | ≥ 5 h | Overall | None | < 1 h | 1 to < 3 h | 3 to < 5 h | ≥ 5 h | |

| Overall prevalence | 4.4 | 19.0 | 33.4 | 17.7 | 25.4 | 10.2 | 35.1 | 32.7 | 10.3 | 11.6 | ||

| Online harassment | ||||||||||||

| Not involved | 61.3 | 5.9 | 23.5 | 36.7 | 16.0 | 17.8 | 74.9 | 12.3 | 37.1 | 32.0 | 9.0 | 9.6 |

| Victim | 22.5 | 3.1 | 15.7 | 30.9 | 20.2 | 30.1 | 11.5 | 6.5 | 34.5 | 35.2 | 11.9 | 11.8 |

| Perpetrator | 1.8 | 0.9 | 10.1 | 25.1 | 20.3 | 43.6 | 3.0 | 5.7 | 29.4 | 32.8 | 14.1 | 18.1 |

| Perpetrator-victim | 14.4 | 0.7 | 6.1 | 24.5 | 20.6 | 48.1 | 10.6 | 0.8 | 23.2 | 35.4 | 16.9 | 23.6 |

| Hours of sleep | ||||||||||||

| 10 + h | 16.2 | 10.3 | 30.3 | 33.0 | 13.6 | 12.8 | 20.8 | 14.9 | 41.6 | 29.1 | 7.8 | 6.6 |

| 9 | 38.6 | 4.6 | 20.5 | 37.0 | 17.1 | 20.8 | 40.3 | 10.4 | 38.3 | 31.9 | 9.9 | 9.5 |

| 8 | 31.8 | 2.5 | 15.5 | 32.5 | 20.2 | 29.4 | 28.0 | 7.8 | 30.3 | 35.7 | 11.7 | 14.5 |

| 7 h or less | 13.4 | 1.4 | 9.6 | 25.7 | 18.7 | 44.6 | 10.8 | 7.1 | 22.8 | 35.1 | 12.9 | 22.1 |

| Sleep latency | ||||||||||||

| 0–30 min | 62.6 | 5.1 | 20.4 | 34.5 | 16.6 | 23.4 | 69.3 | 10.1 | 35.9 | 33.2 | 10.2 | 10.5 |

| 31–60 min | 26.8 | 3.5 | 17.5 | 32.8 | 20.2 | 26.0 | 21.4 | 9.8 | 34.1 | 32.4 | 10.9 | 12.8 |

| More than 60 min | 10.7 | 2.9 | 14.5 | 28.9 | 18.1 | 35.7 | 9.2 | 12.6 | 30.9 | 29.5 | 9.8 | 17.2 |

| Sleep disruption | ||||||||||||

| None of the time | 24.6 | 5.7 | 21.1 | 34.0 | 17.4 | 21.8 | 36.1 | 11.7 | 35.3 | 34.0 | 8.4 | 10.6 |

| A little of the time | 35.1 | 4.5 | 20.2 | 35.4 | 17.7 | 22.2 | 36.3 | 9.4 | 37.1 | 33.6 | 10.8 | 9.1 |

| Often | 27.6 | 3.5 | 16.6 | 33.8 | 18.1 | 28.0 | 20.2 | 8.2 | 33.1 | 32.3 | 11.9 | 14.4 |

| Most of the time | 12.7 | 3.7 | 16.9 | 26.2 | 17.4 | 35.8 | 7.4 | 12.6 | 29.4 | 23.6 | 13.0 | 21.4 |

| Self-esteem | ||||||||||||

| Normal/high | 87.2 | 4.5 | 20.0 | 34.5 | 17.8 | 23.1 | 91.1 | 9.9 | 35.1 | 33.5 | 10.4 | 11.1 |

| Low | 12.8 | 3.7 | 12.1 | 25.9 | 16.9 | 41.4 | 8.9 | 13.8 | 35.1 | 24.9 | 9.6 | 16.6 |

| Body weight satisfaction | ||||||||||||

| Satisfied | 21.8 | 7.7 | 24.9 | 34.5 | 15.6 | 17.3 | 31.7 | 13.8 | 38.2 | 31.0 | 7.8 | 9.1 |

| Dissatisfied | 78.2 | 3.5 | 17.4 | 33.1 | 18.3 | 27.7 | 68.3 | 8.6 | 33.6 | 33.5 | 11.5 | 12.8 |

| Happiness with appearance | ||||||||||||

| Happy | 84.6 | 4.7 | 19.8 | 34.7 | 18.2 | 22.5 | 88.2 | 10.4 | 35.3 | 33.1 | 10.1 | 11.0 |

| Unhappy | 15.4 | 2.7 | 14.8 | 26.3 | 14.7 | 41.4 | 11.8 | 9.0 | 33.2 | 29.8 | 11.9 | 16.1 |

| Internalising score (age 11) | ||||||||||||

| Normal | 74.5 | 3.5 | 18.7 | 34.5 | 18.9 | 24.2 | 75.0 | 8.5 | 35.1 | 34.4 | 10.7 | 11.3 |

| Borderline/abnormal | 25.5 | 7.0 | 19.8 | 30.2 | 14.1 | 28.9 | 25.0 | 15.5 | 35.1 | 27.6 | 9.3 | 12.5 |

| Family income (fifths) | ||||||||||||

| Richest | 31.5 | 5.9 | 22.5 | 37.2 | 16.9 | 17.6 | 31.4 | 10.7 | 40.7 | 31.6 | 8.8 | 8.3 |

| Fourth | 24.1 | 2.3 | 18.3 | 37.0 | 18.3 | 24.1 | 25.8 | 10.6 | 32.9 | 35.9 | 10.2 | 10.4 |

| Third | 19.1 | 3.1 | 18.1 | 29.8 | 19.5 | 29.5 | 19.2 | 9.4 | 33.7 | 32.7 | 10.8 | 13.4 |

| Second | 14.5 | 4.6 | 14.3 | 27.4 | 19.1 | 34.7 | 13.2 | 10.1 | 30.7 | 32.2 | 13.5 | 13.5 |

| Poorest | 10.8 | 7.2 | 18.4 | 29.1 | 13.8 | 31.6 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 31.9 | 28.8 | 10.2 | 19.1 |

| Family structure | ||||||||||||

| Two parent | 76.8 | 4.8 | 19.8 | 35.3 | 17.5 | 22.6 | 77.5 | 10.4 | 35.9 | 33.2 | 9.9 | 10.6 |

| One parent | 23.2 | 3.3 | 16.3 | 27.1 | 18.5 | 34.8 | 22.5 | 9.8 | 32.3 | 31.1 | 11.7 | 15.0 |

Notes: Prevalence estimates are weighted with sample weights. Sample sizes are unweighted.

Social media use was associated with experiences of online harassment, short sleep hours, the time it takes to fall asleep, sleep disruption, being happy with appearance and body weight satisfaction among girls and boys. Girls and boys living in lower income and one parent households were more likely to use social media for 5 or more hours daily. Having high internalising symptom scores at age 11 was associated with higher prevalences of not using social media (girls 7.0 vs 3.5%; boys 15.5 vs 8.5%). Girls with high internalising symptom scores also had a higher prevalence of social media use for 5 or more hours per day (Table 1).

On average girls had higher depressive symptom scores compared with boys (geometric mean score 4.6 vs 2.5). Online harassment, sleep hours, latency and disruption, self-esteem happiness with appearance and body weight satisfaction were all strongly associated with depressive symptom scores as were internalising symptoms from earlier in adolescence for girls and boys (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (geometric) depressive symptom scores and clinically relevant symptoms (percent) by social media use, explanatory factors and confounders.

| Girls (n = 5496) |

Boys (n = 5408) |

Girls (n = 5496) |

Boys (n = 5408) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric mean score | Clinically relevant symptoms (%) | |||

| Overall | 4.6 | 2.5 | 23.6 | 8.4 |

| Social media use in hours/weekday | ||||

| None | 2.7 | 2.5 | 11.2 | 7.4 |

| < 1 h | 3.3 | 2.3 | 15.1 | 7.2 |

| 1 to < 3 h | 3.9 | 2.3 | 18.1 | 6.8 |

| 3 to < 5 h | 5.2 | 3.0 | 25.1 | 11.4 |

| > 5 h | 6.6 | 3.5 | 38.1 | 14.5 |

| Gender interaction: P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Online harassment | ||||

| Not involved | 3.1 | 2.1 | 13.9 | 5.3 |

| Victim | 7.5 | 4.3 | 35.6 | 17.4 |

| Perpetrator | 6.8 | 3.6 | 32.8 | 7.9 |

| Perpetrator-victim | 8.5 | 4.9 | 44.9 | 20.1 |

| Gender interaction: P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Hours of sleep | ||||

| 10 + h | 2.9 | 2.2 | 13.8 | 6.0 |

| 9 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 17.8 | 6.0 |

| 8 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 25.1 | 9.1 |

| 7 h or less | 8.9 | 4.0 | 48.4 | 19.8 |

| Gender interaction: P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep latency | ||||

| 0–30 min | 3.6 | 2.1 | 15.4 | 6.3 |

| 31–60 min | 6.2 | 3.2 | 33.0 | 9.7 |

| More than 60 min | 9.0 | 4.5 | 47.8 | 20.5 |

| Gender interaction: P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Sleep disruption | ||||

| None of the time | 2.3 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 4.0 |

| A little of the time | 4.1 | 2.5 | 18.0 | 6.0 |

| Often | 6.4 | 3.9 | 32.5 | 14.1 |

| Most of the time | 8.9 | 4.9 | 49.9 | 25.8 |

| Gender interaction: P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Self-esteem | ||||

| Normal/high | 3.4 | 2.3 | 15.7 | 5.5 |

| Low | 13.1 | 10.0 | 77.2 | 38.3 |

| Gender interaction: P value | 0.50 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Body weight satisfaction | ||||

| Satisfied | 2.3 | 1.9 | 8.5 | 3.7 |

| Dissatisfied | 5.5 | 2.8 | 27.8 | 10.5 |

| Gender interaction: P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Happiness with appearance | ||||

| Happy | 3.7 | 2.4 | 16.0 | 6.1 |

| Unhappy | 12.2 | 6.1 | 65.3 | 25.5 |

| Gender interaction: P value | 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Internalising score (age 11) | ||||

| Normal | 4.2 | 2.2 | 21.2 | 6.8 |

| Borderline/abnormal | 5.6 | 3.3 | 30.4 | 13.1 |

| Gender interaction: P value | 0.39 | 0.17 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Family income (fifths) | ||||

| Richest | 4.5 | 2.5 | 20.4 | 6.8 |

| Fourth | 5.3 | 2.9 | 20.9 | 9.0 |

| Third | 5.0 | 2.6 | 26.3 | 8.0 |

| Second | 4.4 | 2.5 | 30.3 | 11.3 |

| Poorest | 4.0 | 2.3 | 24.8 | 8.5 |

| Gender interaction: P value | < 0.001 | 0.03 | ||

| P value for trend | 0.003 | 0.042 | < 0.001 | < 0.05 |

| Family structure | ||||

| Two parent | 4.3 | 2.4 | 22.0 | 7.9 |

| One parent | 5.3 | 2.8 | 28.6 | 10.1 |

| Gender interaction: P value | 0.14 | 0.03 | ||

| P value for trend | < 0.001 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | < 0.05 |

Notes: Estimates are weighted with sample weights. Sample sizes are unweighted. Moods and feelings score ranges from 0 to 26 and scores ≥ 12 indicate clinically relevant depressive symptoms.

Wald tests for gender interaction are based on differences in means of logged depression symptom scores by gender. Tests for differences in means across categories within gender are based on non-parametric trend tests of logged depression symptom scores.

4.1. Is Social Media Use Associated With Depressive Symptoms in Adolescence?

The association between social media use and means of log depressive symptoms was stronger for girls compared with boys (test for interaction, p < 0.001). Among girls, greater daily hours of social media use corresponded to a stepwise increase in depressive symptom scores and in the proportion with clinically relevant symptoms. For boys, higher depressive symptom scores were seen among those reporting 3 or more hours of daily social media use (Table 2).

In regression models (Table 3) Wald tests confirmed that the magnitude of association between social media use and depressive symptoms scores was larger for girls than for boys. In model 0 with 1 to < 3 h as the reference category: for girls and boys using social media for 3 to < 5 h there were 26% vs 21% higher depressive symptoms scores; and for girls and boys with ≥ 5 h use there were 50% vs 35% higher scores respectively.

Table 3.

Multivariable regressions, depressive symptom scores by social media use.

| Model 0 (M0) |

Model 1: M0 + online harassment |

Model 2: M0 + sleep |

Model 3: M0 + self-esteem |

Model 4: M0 + body image |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social media use in hours/weekday | ||||||||||

| Panel A: girls (n = 5496) | ||||||||||

| None | 0.74⁎⁎⁎ | (0.62 to 0.89) | 0.84⁎ | (0.71 to 0.99) | 0.87 | (0.74 to 1.02) | 0.77⁎⁎ | (0.65 to 0.91) | 0.88 | (0.76 to 1.01) |

| < 1 h | 0.88⁎⁎ | (0.80 to 0.96) | 0.94 | (0.86 to 1.02) | 0.93 | (0.86 to 1.00) | 0.87⁎⁎⁎ | (0.80 to 0.95) | 0.96 | (0.89 to 1.03) |

| 1 to < 3 h (ref) | ||||||||||

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.26⁎⁎⁎ | (1.15 to 1.37) | 1.17⁎⁎⁎ | (1.08 to 1.26) | 1.18⁎⁎⁎ | (1.09 to 1.28) | 1.20⁎⁎⁎ | (1.10 to 1.30) | 1.17⁎⁎⁎ | (1.08 to 1.26) |

| > 5 h | 1.50⁎⁎⁎ | (1.39 to 1.62) | 1.30⁎⁎⁎ | (1.21 to 1.40) | 1.28⁎⁎⁎ | (1.19 to 1.38) | 1.26⁎⁎⁎ | (1.17 to 1.35) | 1.30⁎⁎⁎ | (1.21 to 1.40) |

| Wald test, F(4,387) | 48 | P < 0.00005 | 21 | P < 0.00005 | 22 | P < 0.00005 | 31 | P < 0.00005 | 21 | P < 0.00005 |

| Panel B: boys (n = 5408) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 1.01 | (0.91 to 1.11) | 1.11⁎ | (1.01 to 1.23) | 1.06 | (0.97 to 1.16) | 0.98 | (0.89 to 1.08) | 1.10⁎ | (1.01 to 1.20) |

| < 1 h | 0.99 | (0.92 to 1.07) | 1.03 | (0.95 to 1.11) | 1.01 | (0.94 to 1.09) | 0.99 | (0.92 to 1.07) | 1.01 | (0.94 to 1.09) |

| 1 to < 3 h (ref) | ||||||||||

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.21⁎⁎⁎ | (1.08 to 1.35) | 1.16⁎⁎ | (1.04 to 1.30) | 1.15⁎ | (1.03 to 1.27) | 1.18⁎⁎ | (1.06 to 1.32) | 1.17⁎⁎ | (1.05 to 1.31) |

| > 5 h | 1.35⁎⁎⁎ | (1.23 to 1.50) | 1.27⁎⁎⁎ | (1.15 to 1.39) | 1.21⁎⁎⁎ | (1.10 to 1.34) | 1.31⁎⁎⁎ | (1.18 to 1.44) | 1.30⁎⁎⁎ | (1.19 to 1.42) |

| Wald test, F(4,387) | 13 | P < 0.00005 | 8 | P < 0.00005 | 5 | P = 0007 | 11 | P < 0.00005 | 10 | P < 0.00005 |

Notes: All regressions adjust for covariates: family income and structure at age 14, internalising scores at age 11, and age and are weighted with sample weights. Confidence intervals are in parentheses. Sample sizes are unweighted. Regression coefficients have been exponentiated to aid interpretation.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

4.2. Are Online Harassment, Sleep, Self-esteem and Body Image Potential Mediators of the Association Between Social Media Use and Depressive Symptoms?

In multivariate models, adjusting for markers of online harassment, sleep, self-esteem and body image reduced coefficients for associations between social media use and depressive symptom suggesting some mediation (Table 3). Wald tests assess the null hypothesis that the 4 parameters for social media use are simultaneously equal to zero, indicative of full mediation. They confirmed rejection of the null hypothesis; social media use appeared to be partially mediated in models 1–4. Taking each of these hypothesised pathways in turn with 1 to < 3 h of daily use as the reference category, we see that adjustment for online harassment (Model 1) attenuates the association between social media use and depressive symptoms for girls and boys. For 3 to < 5 h there were 17% and 16% higher scores for girls and boys; and for ≥ 5 h there were 30% and 27% higher scores respectively. Similarly, adjustment for markers of sleep (Model 2) reduced depressive symptom score coefficients for girls and boys. For 3 to < 5 h there was a 18% and 15% change; and for ≥ 5 h 28% and 21% change for girls and boys respectively. Adjustment for the marker of self-esteem (Model 3) attenuated associations more for girls than for boys. For 3 to < 5 h there was a 20% and 18% change; and for ≥ 5 h a 26% and 31% change for girls and boys respectively. Adjusting for markers of body image (Model 4) reduced coefficients for girls and boys. For 3 to < 5 h there was a 17% change; and a 30% for ≥ 5 h for both genders. A similar pattern of findings was observed when we considered clinically relevant depressive symptoms as the outcome variable (data available on request).

4.3. What are the Potential Pathways From Social Media Use to Depressive Symptom Scores?

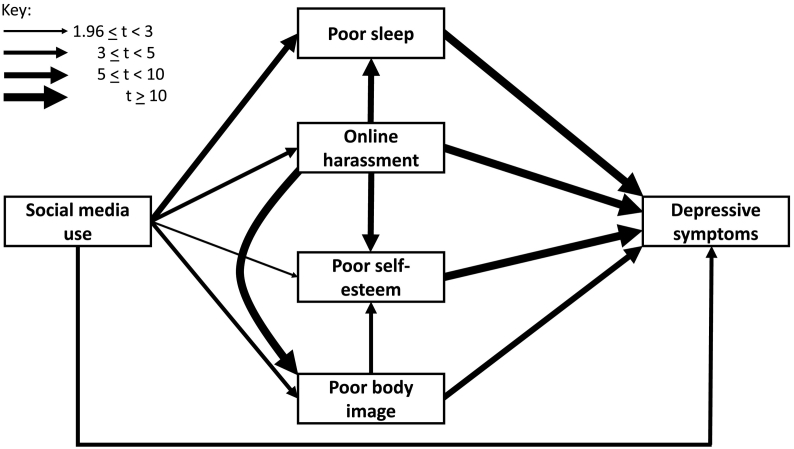

The first path model (not shown) found consistent associations for girls and boys, none of the associations reached the criterion for gender differences. The second model estimated common pathways for girls and boys; Fig. 2 gives a graphical indication of the overall strength of the pathways while Table 4 provides detailed estimates. Support was found for all the hypothesised pathways. In Fig. 2, the width of an arrow indicates the strength of support for that pathway. The most important routes from social media use to depressive symptoms are shown to be via poor sleep and online harassment. There was a simple pathway from social media use to depressive symptoms via poor sleep. The role of online harassment was more complex, with multiple pathways through poor sleep, self-esteem and body image.

Fig. 2.

Social media use and depressive symptoms – summary of path analysis.

Table 4.

Path model from social media use to depressive symptoms score (n = 10,904).

| OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Social media use → hours of sleep1 | ||

| None | 1.86⁎⁎⁎ | (1.56 to 2.22) |

| < 1 h | 1.37⁎⁎⁎ | (1.21 to 1.55) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 0.83⁎⁎ | (0.72 to 0.95) |

| ≥ 5 h | 0.53⁎⁎⁎ | (0.46 to 0.60) |

| Online harassment → hours of sleep1 | ||

| Not involved | Ref | |

| Victim | 0.71⁎⁎⁎ | (0.63 to 0.80) |

| Perpetrator | 0.54⁎⁎⁎ | (0.39 to 0.74) |

| Perpetrator-victim | 0.67⁎⁎⁎ | (0.59 to 0.76) |

| Social media use → sleep latency1 | ||

| None | 1.01 | (0.83 to 1.22) |

| < 1 h | 0.94 | (0.81 to 1.09) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.16 | (0.98 to 1.39) |

| > 5 h | 1.37⁎⁎⁎ | (1.17 to 1.60) |

| Online harassment → sleep latency1 | ||

| Not involved | Ref | |

| Victim | 1.68⁎⁎⁎ | (1.44 to 1.97) |

| Perpetrator | 1.50⁎ | (1.08 to 2.08) |

| Perpetrator-victim | 1.53⁎⁎⁎ | (1.32 to 1.76) |

| Social media use → sleep disruption1 | ||

| None | 0.87 | (0.72 to 1.05) |

| < 1 h | 1.03 | (0.90 to 1.16) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.16⁎ | (1.01 to 1.34) |

| ≥ 5 h | 1.36⁎⁎⁎ | (1.18 to 1.56) |

| Online harassment → sleep disruption1 | ||

| Not involved | Ref | |

| Victim | 1.93⁎⁎⁎ | (1.70 to 2.20) |

| Perpetrator | 1.21 | (0.90 to 1.62) |

| Perpetrator-victim | 1.93⁎⁎⁎ | (1.66 to 2.23) |

| Social media use → body weight dissatisfaction2 | ||

| None | 0.60⁎⁎⁎ | (0.48 to 0.76) |

| < 1 h | 0.83⁎⁎ | (0.72 to 0.96) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.09 | (0.89 to 1.32) |

| > 5 h | 1.31⁎⁎ | (1.10 to 1.56) |

| Online harassment → body weight dissatisfaction2 | ||

| Not involved | Ref | |

| Victim | 1.34⁎⁎⁎ | (1.13 to 1.59) |

| Perpetrator | 1.15 | (0.74 to 1.79) |

| Perpetrator-victim | 1.71⁎⁎⁎ | (1.41 to 2.06) |

| Social media use → low self-esteem2 | ||

| None | 1.75⁎⁎ | (1.19 to 2.58) |

| < 1 h | 1.21 | (0.94 to 1.57) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.05 | (0.82 to 1.34) |

| > 5 h | 1.56⁎⁎⁎ | (1.25 to 1.95) |

| Online harassment → low self-esteem2 | ||

| Not involved | Ref | |

| Victim | 2.03⁎⁎⁎ | (1.66 to 2.47) |

| Perpetrator | 1.81 | (1.00 to 3.27) |

| Perpetrator-victim | 1.99⁎⁎⁎ | (1.56 to 2.53) |

| Happiness with appearance → low self-esteem2 | ||

| 25.89⁎⁎⁎ | (16.45 to 40.76) | |

| Body weight dissatisfaction → low self-esteem2 | ||

| 2.00⁎⁎⁎ | (1.52 to 2.64) | |

| Social media use → online harassment3 | ||

| Victim | ||

| None | 0.51⁎⁎⁎ | (0.38 to 0.68) |

| < 1 h | 0.78⁎⁎ | (0.66 to 0.93) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.35⁎⁎ | (1.11 to 1.63) |

| > 5 h | 1.64⁎⁎⁎ | (1.37 to 1.97) |

| Perpetrator | ||

| None | 0.32⁎⁎ | (0.15 to 0.68) |

| < 1 h | 0.83 | (0.52 to 1.34) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 2.12⁎ | (1.17 to 3.86) |

| > 5 h | 2.71⁎⁎⁎ | (1.71 to 4.28) |

| Perpetrator-victim | ||

| None | 0.09⁎⁎⁎ | (0.05 to 0.17) |

| < 1 h | 0.54⁎⁎⁎ | (0.43 to 0.69) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 1.69⁎⁎⁎ | (1.35 to 2.12) |

| > 5 h | 2.69⁎⁎⁎ | (2.24 to 3.24) |

| b (95% CI) | ||

| Social media use → happiness with appearance4 | ||

| None | − 0.10⁎⁎⁎ | (− 0.16 to − 0.04) |

| < 1 h | − 0.03⁎ | (− 0.06 to 0.00) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 0.05⁎ | (0.01 to 0.09) |

| > 5 h | 0.08⁎⁎⁎ | (0.05 to 0.12) |

| Online harassment → happiness with appearance4 | ||

| Not involved | Ref | |

| Victim | 0.22⁎⁎⁎ | (0.18 to 0.26) |

| Perpetrator | 0.13⁎⁎ | (0.03 to 0.22) |

| Perpetrator-victim | 0.21⁎⁎⁎ | (0.18 to 0.25) |

| Social media use → SMFQ score4 | ||

| None | 0.09⁎⁎⁎ | (0.02 to 0.17) |

| < 1 h | 0.10 | (− 0.04 to 0.06) |

| 1 to < 3 h | Ref | |

| 3 to < 5 h | 0.10⁎⁎⁎ | (0.04 to 0.16) |

| > 5 h | 0.10⁎⁎⁎ | (0.05 to 0.16) |

| Online harassment → SMFQ score4 | ||

| Not involved | Ref | |

| Victim | 0.33⁎⁎⁎ | (0.28 to 0.38) |

| Perpetrator | 0.30⁎⁎⁎ | (0.20 to 0.39) |

| Perpetrator-victim | 0.38⁎⁎⁎ | (0.33 to 0.43) |

| Hours of sleep → SMFQ score4 | ||

| 7 h or less | 0.17⁎⁎⁎ | (0.11 to 0.22) |

| 8 | 0.11⁎⁎⁎ | (0.07 to 0.16) |

| 9 | Ref | |

| 10 + h | − 0.06⁎ | (− 0.11 to − 0.01) |

| Sleep latency → SMFQ score4 | ||

| 0–30 min | Ref | |

| 31–60 min | 0.13⁎⁎⁎ | (0.08 to 0.17) |

| > 60 min | 0.21⁎⁎⁎ | (0.14 to 0.27) |

| Sleep disruption → SMFQ score4 | ||

| None of the time | Ref | |

| A little of the time | 0.23⁎⁎⁎ | (0.19 to 0.28) |

| Often | 0.40⁎⁎⁎ | (0.35 to 0.45) |

| Most of the time | 0.48⁎⁎⁎ | (0.42 to 0.54) |

| Low self-esteem → SMFQ score4 | ||

| 0.56⁎⁎⁎ | (0.51 to 0.61) | |

| Happiness with appearance → SMFQ score4 | ||

| 0.47⁎⁎⁎ | (0.43 to 0.51) | |

| Body weight dissatisfaction → SMFQ score4 | ||

| 0.14⁎⁎⁎ | (0.10 to 0.18) | |

Notes [1]: Ordinal logistic regression [2]; Logistic regression [3]; Multinomial logistic regression [4]; Linear regression. All regressions adjust for confounders: family income and structure at age 14, internalising scores at age 11 and age. Regression estimates are weighted with sample weights. Confidence intervals are in parentheses. Sample sizes are unweighted.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

In more detail (Table 4), greater social media use was related to less sleep, taking more time to fall asleep and more disruptions. For example, ≥ 5 h using social media was associated with ≈ 50% lower odds of 1 h more sleep. In turn, depressive symptom scores were higher for girls and boys experiencing poor sleep (≤ 7 h associated with 19% (exp 0.17) higher scores than 9 h sleep). Both ≥ 5 h on social media and no social media use were related to low self-esteem (56% and 75% respectively, vs. 1 to < 3 h). In turn, self-esteem strongly predicted higher depressive symptom scores (75% higher). More hours using social media was related to body weight dissatisfaction and unhappiness with appearance (≥ 5 h 31% more likely to be dissatisfied and 8% higher unhappiness with appearance scores than 1 to < 3 h). In turn, body image was linked to depressive symptom scores both directly (body dissatisfaction 15% higher depressive symptom scores and 10% greater unhappiness with appearance scores with 5% (1.100.47) higher depressive symptom scores) and indirectly via poor self-esteem. Finally, social media use was related to involvement with online harassment (≥ 5 h victim odds ratio 1.64; perpetrator 2.71; perpetrator-victim 2.69) which had direct and indirect associations (via sleep, poor body image and self-esteem) with depressive symptom scores. There was still an independent association between social media use and depressive symptom scores, “unexplained” by the mediating factors (≥ 5 h 11% higher scores).

5. Discussion

Among 14-year olds living in the UK, we found an association between social media use and depressive symptoms and that this was stronger for girls than for boys. The magnitude of these associations reduced when potential explanatory factors were taken into account, suggesting that experiences of online harassment, poorer sleep quantity and quality, self-esteem and body image largely explain observed associations. There was no evidence of differences for girls and boys in hypothesised pathways between social media use and depressive symptoms. Findings are based largely on cross sectional data and thus causality cannot be inferred.

Consistent with other studies we found an association between social media use and depressive symptoms – a finding that has been replicated using several cross sectional and longitudinal data sources [7], [8]. Our finding of gender differences in the magnitude of association between social media use and depressive symptoms is consistent with our previous research using prospective data from the UK Household Longitudinal Study [9] which showed that girls with greater social media use at the start of adolescence had poorer mental wellbeing several years on. However, our prior work did not look at potential pathways between social media use and wellbeing, and in the current study we did not find evidence to suggest differences for girls and boys in the pathways at play. Our findings are consistent with prior research which has typically investigated one or two potential mechanisms at a time, for instance online harassment [12], [13], [14], sleep [18], [19], [20], self-esteem [22] and body image [24], [25]. We found support for hypothesised mechanisms whereby social media use was associated with poor sleep, involvement with online harassment, low self-esteem and poor body image, which in turn were all related to depressive symptoms. Moreover, we found support for our hypotheses linking pathways – specifically adolescents experiencing online harassment were more likely to have poor sleep, poor body image and low self-esteem; and that girls and boys with poor body image were more likely to have low self-esteem. However, caution is needed when interpreting our findings as the data used in this paper were, for the most part, cross sectional and the direction of association and therefore causality cannot be inferred.

Our study has distinct strengths - firstly, we used data from a large scale representative contemporary UK setting making our findings generalisable to the wider population. Secondly, we were able to simultaneously investigate four hypothesised mechanisms – experiences of online harassment, sleep quantity and quality, self-esteem and body image – which have been proposed as pathways between social media use and mental health in young people. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to have investigated multiple potential pathways in this way. Even though our findings are based largely on cross sectional data, in path modelling we were able to explicitly test hypothesised causal mechanisms adding weight to our findings. On the other hand, in addition to cross sectionality, our study has distinct limitations. Due to data availability we were not able to take account of some factors hypothesised to be on the pathway between social media use and poor mental health. For instance, research from elsewhere has characterised types of social media use – active use being associated with positive outcomes versus passive use which tends to be correlated with negative outcomes [8]. We were not able to investigate the role of level of emotional investment in time spent online and young people's experiences of ‘fear of missing out’. Nor were we able to take account of the time of day young people were online, night time use of screens being linked to disrupted sleep patterns [21]. There is the distinct possibility of a cyclical relationship between social media use and depressive symptoms. In an attempt to deal with this in our modelling we took account of problems related to depressed mood from earlier in adolescence to try and rule out the possibility that 11-year olds with more negative affect would be lighter or heavier users of social media later on in adolescence. We found that girls with higher internalising symptoms earlier in adolescence tended to either be non-users or particularly heavy users of social media whilst boys with negative affect earlier in adolescence were likely to be non-users thus underlining the likely complex patterns at play and the importance of taking these data into account in our analyses. There is a risk that self-reported data of time spent on social media use might lack accuracy, use may be especially difficult for young people to estimate in time categories as social media is not clearly delineated, unlike other forms of screen based media (including TV viewing and playing games). However, the questions used were similar to those from other large-scale population based surveys including the UK Household Longitudinal Study [9] and Ofcom [5]. Furthermore, the estimates of time spent using social media presented in our paper are consistent with those reported from other UK studies [9], [34]. Similarly, self-reported sleep measures may be prone to bias, but these have previously been shown to reliably capture sleep patterns in large scale surveys of adolescents [35].

Our findings add weight to the growing evidence base on the potential pitfalls associated with lengthy time spent engaging on social media. These findings are highly relevant to current policy development on guidelines for the safe use of social media and calls on industry to more tightly regulate hours of social media use for young people [10], [11]. Clinical, educational and family settings are all potential points of contact whereby young people could be encouraged to reflect not only on their social media use but also other aspects of their lives including online experiences and their sleep patterns. For instance, in the home setting all family members could reflect on patterns of use and have in place limits for time online, curfews for use and the overnight removal of mobile devices from bedrooms. School settings present opportunities for children and young people to learn how to navigate online life appropriately and safely and for interventions aimed at promoting self-esteem. Clearly a large proportion of young people experience dissatisfaction with the way they look and how they feel about their bodies and perhaps a broader societal shift away from the perpetuation of what are often highly distorted images of idealised beauty could help shift these types of negative perceptions.

Clearly there are many benefits to be gained for young people by engaging online. Our results and those of others highlight the likely complexity of mechanisms at play. Future research using prospectively collected data from the same population sample with the use of repeated measures and the application of causal analyses will help to provide a more comprehensive picture of the relationship between social media use and young people's mental health. Given the short- and long-term implications of having poor mental health, improving our understanding of underlying processes could help identify opportunities for interventions with benefits across the lifecourse [4].

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Millennium Cohort Study families for their time and cooperation, as well as the Millennium Cohort Study team at the Institute of Education. The Millennium Cohort Study is funded by grants from Economic and Social Research Council. YK, AS and AZ received funding from Economic and Social Research Council (ES/R008930/1) during the conduct of the study.

Ethical approval was not required for this study as the analysis involved secondary analysis of publicly available data.

Data are available on request from the authors.

References

- 1.Patton G., Borschmann R. Responding to the adolescent in distress. Lancet. 2017;390(10094):536–538. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31331-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health . Department of Health; London: 2015. Future in mind: promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people's mental health and wellbeing. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin K.A., King K. Developmental trajectories of anxiety and depression in early adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43(2):311–323. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9898-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler R.C., Amminger G.P., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Alonso J., Lee S., Üstün T. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ofcom . 2017. Children and parents: media use and attitudes report. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenhart A. Pew Research Center; 2015. Teen, social media and technology overview 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu M., Wu L., Yao S. Dose-response association of screen time-based sedentary behaviour in children and adolescents and depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(20):1252–1258. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verduyn P., Ybarra O., Resibois M., Jonides J., Kross E. Do social network sites enhance or undermine subjective well-being? A critical review. Soc Iss Policy Rev. 2017;11(1):274–302. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Booker C.L., Kelly Y.J., Sacker A. Gender differences in the associations between age trends of social media interaction and well-being among 10–15 year olds in the UK. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):321. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5220-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal Society for Public Health . Royal Society for Public Health; London, UK: 2017. #StatusOfMind: social media and young people's mental health and wellbeing. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Children's Commissioner . 2018. Life in 'likes': Report into social media use among 8–12 year olds. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahy A.E., Stansfeld S.A., Smuk M., Smith N.R., Cummins S., Clark C. Longitudinal associations between cyberbullying involvement and adolescent mental health. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(5):502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Livingstone S., Smith P.K. Annual research review: harms experienced by child users of online and mobile technologies: the nature, prevalence and management of sexual and aggressive risks in the digital age. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(6):635–654. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tokunaga R.S. Following you home from school: a critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(3):277–287. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemola S., Perkinson-Gloor N., Brand S., Dewald-Kaufmann J.F., Grob A. Adolescents' electronic media use at night, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms in the smartphone age. J Youth Adolesc. 2015;44(2):405–418. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0176-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly Y., Kelly J., Sacker A. Changes in bedtime schedules and behavioral difficulties in 7 year old children. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):e1184–e1193. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gangwisch J.E., Babiss L.A., Malaspina D., Turner B.J., Zammit G.K., Posner K. Earlier parental set bedtimes as a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideation. Sleep. 2010;33(1):97–106. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods H.C., Scott H. #Sleepyteens: social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2016;51:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shochat T., Flint-Bretler O., Tzischinsky O. Sleep patterns, electronic media exposure and daytime sleep-related behaviours among Israeli adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(9):1396–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garmy P., Nyberg P., Jakobsson U. Sleep and television and computer habits of Swedish school-age children. J Sch Nurs. 2012;28(6):469–476. doi: 10.1177/1059840512444133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cain N., Gradisar M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: a review. Sleep Med. 2010;11(8):735–742. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orth U., Maes J., Schmitt M. Self-esteem development across the life span: a longitudinal study with a large sample from Germany. Dev Psychol. 2015;51(2):248–259. doi: 10.1037/a0038481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valkenburg P.M., Koutamanis M., Vossen H.G.M. The concurrent and longitudinal relationships between adolescents' use of social network sites and their social self-esteem. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;76:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frison E., Eggermont S. “Harder, better, faster, stronger”: negative comparison on Facebook and Adolescents' life satisfaction are reciprocally related. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19(3):158–164. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vries D.A., Peter J., de Graaf H., Nikken P. Adolescents' social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: testing a mediation model. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45(1):211–224. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0266-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fardouly J., Vartanian L.R. Social media and body image concerns: current research and future directions. Curr Opin Psychol. 2016;9:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 27.University of London, Institute of Education, Centre for Longitudinal Studies . UK Data Service; 2017. Fitzsimons E. Millennium Cohort Study: sixth survey, 2015. SN: 8156. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angold A., Costello E.J., Messer S.C., Pickles A. Development of a short questionnaire for use in epidemiological studies of depression in children and adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1995;5(4):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thabrew H., Stasiak K., Bavin L.M., Frampton C., Merry S. Validation of the mood and feelings questionnaire (MFQ) and short mood and feelings questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018 doi: 10.1002/mpr.1610. e1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenberg M. Rev. ed. Wesleyan University Press; Middletown, Conn: 1989. Society and the adolescent self-image. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Information for researchers and professionals about the strengths & difficulties questionnaires. http://www.sdqinfo.org [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.White I.R., Royston P., Wood A.M. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin D.B. Hoboken; 2009. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booker C.L., Skew A.J., Kelly Y.J., Sacker A. Media use, sports participation, and well-being in adolescence: cross-sectional findings from the UK household longitudinal study. Am J Public Health. 2014;(0):e1–e7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolfson A.R., Carskadon M.A., Acebo C. Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep. 2003;26(2):213–216. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]