Abstract

Background

Patients with palpitations and pre-syncope commonly present to Emergency Departments (EDs) but underlying rhythm diagnosis is often not possible during the initial presentation. This trial compares the symptomatic rhythm detection rate of a smartphone-based event recorder (AliveCor) alongside standard care versus standard care alone, for participants presenting to the ED with palpitations and pre-syncope with no obvious cause evident at initial consultation.

Methods

Multi-centre open label, randomised controlled trial. Participants ≥ 16 years old presenting to 10 UK hospital EDs were included. Participants were randomised to either (a) intervention group; standard care plus the use of a smartphone-based event recorder or (b) control group; standard care alone. Primary endpoint was symptomatic rhythm detection rate at 90 days. Trial registration number NCT02783898 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Findings

Two hundred forty-three participants were recruited over an 18-month period. A symptomatic rhythm was detected at 90 days in 69 (n = 124; 55.6%; 95% CI 46.9–64.4%) participants in the intervention group versus 11 (n = 116; 9.5%; 95% CI 4.2–14.8) in the control group (RR 5.9, 95% CI 3.3–10.5; p < 0.0001). Mean time to symptomatic rhythm detection in the intervention group was 9.5 days (SD 16.1, range 0–83) versus 42.9 days (SD 16.0, range 12–66; p < 0.0001) in the control group. The commonest symptomatic rhythms detected were sinus rhythm, sinus tachycardia and ectopic beats. A symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia was detected at 90 days in 11 (n = 124; 8.9%; 95% CI 3.9–13.9%) participants in the intervention group versus 1 (n = 116; 0.9%; 95% CI 0.0–2.5%) in the control group (RR 10.3, 95% CI 1.3–78.5; p = 0.006).

Interpretation

Use of a smartphone-based event recorder increased the number of patients in whom an ECG was captured during symptoms over five-fold to more than 55% at 90 days. This safe, non-invasive and easy to use device should be considered part of on-going care to all patients presenting acutely with unexplained palpitations or pre-syncope.

Funding

This study was funded by research awards from Chest, Heart and Stroke Scotland (CHSS) and British Heart Foundation (BHF) which included funding for purchasing the devices. MR was supported by an NHS Research Scotland Career Researcher Clinician award.

Keywords: Ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring, Cardiac arrhythmias, Palpitations, Pre-syncope

Research in Context

Evidence Before This Study

Palpitations and pre-syncope are together responsible for 300,000 annual Emergency Department (ED) attendances in the United Kingdom (UK) alone. Diagnosis of the underlying rhythm is difficult as many patients are fully recovered by the time of attendance, and examination and presenting ECG are commonly normal. Palpitations are typically intermittent, and a diagnosis can only be made through establishing a symptom–rhythm correlation. There have been few studies investigating the use of smartphone-based event recorders; none have been randomised trials and none have studied acute or ED populations. Most previous research in this area has focused on primary and secondary prevention of stroke through the detection of atrial fibrillation.

Added Value of Study

This trial sought to clarify whether there is any benefit to adding a smartphone-based electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring event recorder to standard care. The trial recruited patients presenting to the ED with palpitations and pre-syncope and no obvious cause in the ED. The principal outcome measure was the rate of detection of the underlying symptomatic rhythm at 90 days. This study shows that use of a smartphone-based event recorder increased the number of patients in whom an ECG was captured during symptoms over five-fold to more than 55% at 90 days. These are clinically significant rhythms as they diagnose the underlying cause of the patient's symptoms. The smartphone-based event recorder also increased the number of patients diagnosed with cardiac arrhythmia.

Implications of All the Available Evidence

A smartphone-based event recorder should be considered as part of on-going care for all patients presenting acutely to EDs with unexplained palpitations or pre-syncope. It is safe, non-invasive, easy to use and far more efficient at diagnosing the underlying cause of the patient's symptoms than current standard care, which in the healthcare system studied does not serve this patient group well.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Background

Palpitations (the noticeable pounding, fluttering or irregular beating of the heart) and pre-syncope (the sense of impending loss of consciousness) are together responsible for 1% of Emergency Department (ED) visits (300,000 annual ED attendances in the UK) [1], [2]. Diagnosis of the underlying rhythm is difficult as many patients are fully recovered by the time that they are seen in the ED. Examination and presenting electrocardiogram (ECG) are commonly normal. Once captured, the symptomatic rhythm underlying about 9 in 10 episodes is benign, e.g., normal sinus rhythm, sinus tachycardia or frequent ectopics (extra or skipped heart beats) [3]. However around 1 in 10 patients do have a cardiac arrhythmia as their symptomatic rhythm [3].

The only way to establish the underlying heart rhythm is to capture an ECG whilst the patient has symptoms. Many patients go for years without diagnosis due to the difficulty in capturing the underlying heart rhythm. Recommended first line investigation of 12-lead ECG [4] and conventional ambulatory monitoring (Holter or event monitoring) [5], [6] are of limited efficacy due to the infrequency of symptoms in many patients [5], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Most patients are discharged from the ED and asked to represent or call an ambulance should they get further symptoms in the hope of increasing the chances of capturing the episode on a standard 12-lead ECG.

If patients are referred to cardiology services for assessment, investigation usually starts with a Holter monitor but non-compliance and lack of extended monitoring reduces diagnostic yield to less than 20% [11]. Traditional event recorders, external continuous loop recorders and implantable loop recorders are expensive and not recommended for a patient group who rarely have malignant arrhythmias and may have prolonged periods between episodes.

Recent technological advances have led to several novel ECG monitoring devices appearing on the market [12], [13]. The pocket sized AliveCor (now Kardia) mobile (AliveCor, San Francisco, USA) is a monitoring device that requires the patient to trigger the ECG recording [14]. With minimal training, two fingers from each hand are placed on the monitor (which can be connected to the back of a smartphone) for 30 s to take an ECG recording, which is transmitted wirelessly to the app, analysed and synchronised to an encrypted server. The patient can then alert their healthcare professional to allow their ECG to be viewed securely [14]. The device is supported for clinical use by a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) technology appraisal [14] and was initially developed for detecting AF, for which the automatic diagnostic algorithm has excellent sensitivity (96.6%) and specificity (94%) for correctly interpreting AF versus normal sinus rhythm [15]. There have been several studies investigating the use of smartphone-based event recorders including AliveCor for population screening for AF in various settings [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21] and feasibility for other rhythm disorders [3], [22], [23], [24]. Whilst AliveCor has now undergone assessment against conventional care for AF detection [25], it has yet to be assessed against standard care for the broader investigation of palpitations and arrhythmia assessment. There have been no studies in an acute or ED population, where large numbers of patients present [2].

The primary aim of this study is to compare the symptomatic rhythm detection rate at 90 days of a smartphone-based event recorder (AliveCor) alongside standard care, compared to standard care alone, for participants presenting to the ED with palpitations and pre-syncope with no obvious cause evident at initial consultation.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

Multi-centre open label randomised controlled trial in EDs and Acute Medical Units (AMU) of 10 tertiary and district general hospitals in the UK. A favourable ethical opinion was obtained from the South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee 02 (REC reference: 16/SS/0074) and from the HRA.

2.2. Participants

Participants aged 16 years or over presenting with an episode of palpitations or pre-syncope and whose underlying ECG rhythm during these episodes remains undiagnosed after ED assessment. Written consent was obtained from all participants.

Table 1 shows inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria were: |

|

|

|

| Exclusion criteria were: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Randomisation

Participants were equally distributed between the two study groups. To balance site-level characteristics and ensure investigators could not predict the group allocation of the next-to-be enrolled patient, randomisation was by permuted block randomisation by site. Sealed opaque envelopes containing either ‘Standard Care plus Device’ or ‘Standard Care’ cards were prepared by a central administrator not involved in the study. Blocks were randomly labelled using random number generation with site-specific study participation numbers and sent to each local study team. Participants eligible for inclusion were randomised by the local study team by taking the next lowest consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelope.

4. Procedures

The local direct care team screened and identified potential participants using ED or the AMU triage information and clinical or electronic records. Potentially eligible participants were assessed for study inclusion by the attending clinician. If the potential participant fulfilled the study eligibility criteria, they were given a Participant Information Sheet. Afterwards, if agreeable, written consent was taken. Participants were allocated either (a) INTERVENTION group; standard care plus the use of a smartphone-based event recorder or (b) CONTROL group; standard care, depending on study envelope allocation. All intervention group participants were given an AliveCor Heart Monitor and trained in the use of the device and app in the ED or AMU by the research team. Control group participants received no other intervention. Participants in both groups were admitted, referred or discharged by the treating clinician according to current local hospital protocols. Participants in both groups were followed up at 90 days through hospital record systems (paper or electronic depending on local policy), GP records and by telephone by the local study team. Participants were also asked to complete a standardised written questionnaire. They also received a follow-up telephone call from the local study team enquiring about symptoms and contact with medical services. Participants were also asked about satisfaction and compliance.

If a participant allocated to the intervention group had an episode of palpitations or pre-syncope and was able to record an AliveCor Heart Monitor ECG during the episode, the participant emailed the ECG at a convenient time to the secure (nhs.net) email address of the coordinating Edinburgh research team. This email included a Portable Document Format (pdf) file attachment of the ECG tracing along with the participant's AliveCor app login (which was their study number; no identifiable participant data left the local site).

The AliveCor app rhythm analysis algorithm automatically reported any ECG recorded as Normal, Atrial Fibrillation or Unclassified. The duty Consultant Emergency Physician at the coordinating Edinburgh centre along with a trial team Emergency Physician reviewed the ECG. The central study team contacted the local study team to arrange follow-up if required. In cases of disagreement, the central cardiology team were contacted for further opinion.

If specialist follow-up of the ECG tracing was not required, the local study team wrote to the participant informing them and asked them to arrange follow-up with their general practitioner (GP) who was also contacted with the report. Participants continued to record ECGs for the duration of the study period, but the participant and GP were not contacted again if participants recorded further ECGs that similarly did not require specialist follow-up.

If the participant's ECG recorded a serious cardiac arrhythmia, i.e.,

-

•

ventricular tachyarrhythmia

-

•

complete or 3rd degree heart block

-

•

second degree heart block type II (assumed to be symptomatic given the participant had chosen to record an ECG during the episode)

-

•

pause > 6 s

-

•

symptomatic bradycardia < 40 beats/min

during the study period, the central study team contacted the local study team who alerted the participant immediately by telephone, and referred them urgently to their local ED or cardiac electrophysiology service (as per local protocol).

Participants were asked to use a participant symptom diary to record any symptoms and include time and date, type of symptom and whether they were able to record an ECG during the symptoms. They returned this diary to the local study team along with the participant satisfaction and compliance questionnaire, and smartphone-based event recorder at the end of the 90 days in a pre-paid stamped, addressed envelope. Participants failing to do this were reminded by phone. Participant study information identified by study number alone, was collected on a paper Case Report Form and then entered into a specially designed password protected online accessed secure database (REDCAP; http://www.project-redcap.org), the server of which was held within the University of Edinburgh. The primary outcome was assessed by each local study team.

5. Outcomes

5.1. Primary Outcome

-

1.

Symptomatic rhythm detection rate of a smartphone-based event recorder for symptomatic rhythm detection at 90 days versus standard care.

A ‘symptomatic rhythm’ will be any ECG rhythm recorded during an episode of palpitations or pre-syncope allowing symptom–rhythm correlation. This can be either via the AliveCor Heart Monitor ECG or through standard care.

5.2. Secondary Outcomes

-

1.

Symptomatic rhythm detection rate of a smartphone-based event recorder for cardiac arrhythmia detection at 90 days versus standard care.

-

2.

Time to detection of symptomatic rhythm using a smartphone-based event recorder versus standard care.

-

3.

Time to detection of symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia (rhythm that is not sinus rhythm/sinus tachycardia/ectopic beats) using a smartphone-based event recorder versus standard care.

-

4.

Number of participants treated or (planned for treatment) for cardiac arrhythmia in participants using a smartphone-based event recorder versus standard care.

-

5.

Participant satisfaction and monitor compliance.

-

6.

Cost-effectiveness analysis.

-

7.

Serious outcomes at 90 days: all cause death and major adverse cardiac events [MACE] (myocardial infarction, life-threatening arrhythmia, insertion of a pacemaker or internal cardiac defibrillator, insertion of pacing wire).

5.3. Assessment of Safety and Adverse Events

Serious outcomes were routinely collected as part of the study. The only adverse events recorded were those directly related to the use of the smartphone-based event recorder and application.

5.4. Statistical Methods

5.4.1. Sample Size

Using a symptomatic rhythm detection rate at 90 days of 25% [4] versus standard care (10%), we estimated that 110 participants in each group would have 80% power to determine an absolute 15 percentage point improvement in symptomatic rhythm detection. We aimed to recruit an extra 10% in each group to allow for drop out (i.e., 121 participants in each group).

5.4.2. Analysis

Descriptive analysis of participants are presented split by allocated study group. Baseline to 90-day change in diagnostic yield between the two study groups was analysed using comparison of proportions tests. Additional comparison of proportions tests were used to compare further categorical binary variables between study groups (where expected counts were small the p-value from the Fisher's test was used instead). Categorical variables were compared using a χ2 test (and χ2 test for trend if appropriate). Log-rank tests and Kaplan–Meier curves were used to examine if the smartphone recorder had an effect on the time to detection of symptomatic rhythm and symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia separately up to 90 days versus standard care. All participants were analysed on an intention to treat basis. Statistical significance was determined as p < 0.05 for all outcomes with an acknowledgment of increased type I error risk in the secondary outcomes not considered in the power calculation.

5.4.2.1. Economic Analysis

Overall and median healthcare utilisation costs (primary/community/secondary care and intervention costs) were calculated for both groups. The costing scope included primary care, secondary care and community NHS costs obtained from 2016/17 NHS reference cost data. A Mann–Whitney test was used to examine the overall cost-effectiveness between the smartphone-based event recorder and standard care. Healthcare utilisation costs per symptomatic rhythm diagnosis were calculated for both groups using overall healthcare utilisation cost and number of patients with a symptomatic rhythm in each group.

Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). The sponsor deemed that a data monitoring committee was not required. This trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (trial registration number NCT02783898), and the protocol published in Trials [26].

6. Results

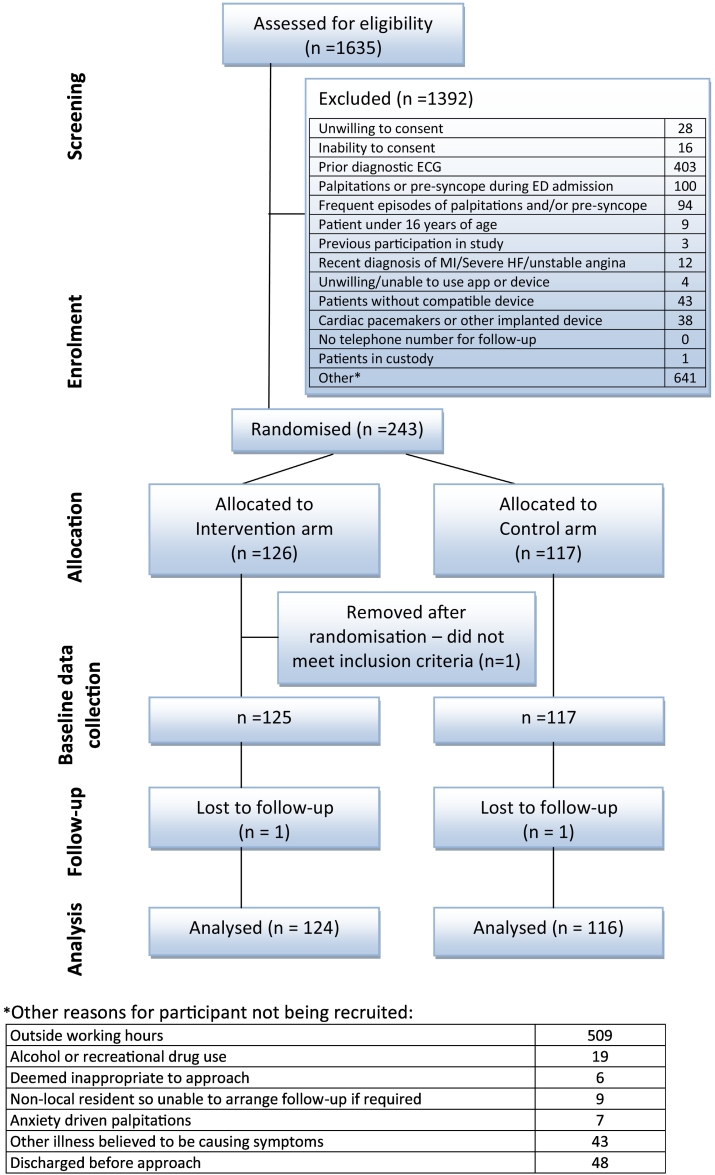

Between 4 July 2016 and 9 January 2018, 243 participants were recruited to the study at 10 centres (Edinburgh 66 participants, 27.2%, Reading 57, 23.5%, Royal London 43, 17.7%, Exeter 24, 9.9%, Plymouth 15, 6.2%, Chesterfield 12, 4.9%, Leicester 12, 4.9%, Musgrove Park 5, 2.1%, Nottingham 5, 2.1%, Whipps Cross 4, 1.6%). Fig. 1 details the study recruitment diagram, and Table 2 details the baseline characteristics of enrolled participants. One hundred twenty-six participants were allocated to the intervention group and 117 to the control group. Two hundred nineteen (90.5%) participants presented with palpitations and 23 (9.5%) with pre-syncope. One participant was removed from the study by the local study team after being randomised, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Baseline data were therefore collected on 125 participants in the intervention group and 117 in the control group. Participants ranged from 17 to 74 years of age with a mean age of 39.5 (SD 13.7). Table 3 details examination findings, initial ECG and management. One participant in each group was lost to follow-up leaving 124 participants available for analysis in the study group and 116 in the control group.

Fig. 1.

Study recruitment diagram.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study population.

| Data are n (%) unless stated. N = 242 (125/117) unless stated. Different denominators due to missing data | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention n = 125 |

Control n = 117 |

Total n = 242 |

|||||

| Gender: Male | 51 | 40.8 | 54 | 46.2 | 105 | 43.4 | |

| Age in years/mean (SD) | 40.0 (14.0) | 39.1 (13.5) | 39.6 (13.8) | ||||

| Number of episodes palpitations or pre-syncope in last 24 h/median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | 1.0 (1.0–3.0) | ||||

| History of presenting episode | Palpitations | 110 | 88.0 | 109 | 93.2 | 219 | 90.5 |

| Pre-syncope | 15 | 12.0 | 8 | 6.8 | 23 | 9.5 | |

| Estimated length of presenting (last) episode | 1 min or less | 19 | 15.2 | 19 | 16.2 | 38 | 15.7 |

| 10 min or less | 31 | 24.8 | 37 | 31.6 | 68 | 28.1 | |

| 1 h or less | 27 | 21.6 | 27 | 23.1 | 54 | 22.3 | |

| More than 1 h | 48 | 38.4 | 34 | 29.1 | 82 | 33.9 | |

| Participants description of symptoms | Anxious | 52 | 41.6 | 50 | 42.7 | 102 | 42.1 |

| Arm or neck pain or tingling | 34 | 27.2 | 33 | 28.2 | 67 | 27.7 | |

| Chest pain or pressure | 51 | 40.8 | 52 | 44.4 | 103 | 42.6 | |

| Dizziness | 62 | 49.6 | 56 | 47.9 | 118 | 48.8 | |

| Faint/Light headed | 73 | 58.4 | 61 | 52.1 | 134 | 55.4 | |

| Pounding | 55 | 44.0 | 56 | 47.9 | 111 | 45.9 | |

| Fluttering | 42 | 33.6 | 38 | 32.5 | 80 | 33.1 | |

| Short of breath | 51 | 40.8 | 49 | 41.9 | 100 | 41.3 | |

| Fast/Racing heart | 77 | 61.6 | 68 | 58.1 | 145 | 59.9 | |

| Skipped/missed heartbeat(s) | 33 | 26.4 | 27 | 23.1 | 60 | 24.8 | |

| Irregular heart beating | 36 | 28.8 | 40 | 34.2 | 76 | 31.4 | |

| How often do they occur? | Never had before | 29 (n = 124) |

23.4 | 29 | 24.8 | 58 (n = 241) |

24.1 |

| Yearly (or even less frequent) | 21 (n = 124) |

16.9 | 27 | 23.1 | 48 (n = 241) |

19.9 | |

| Monthly | 27 (n = 124) |

21.8 | 25 | 21.4 | 52 (n = 241) |

21.6 | |

| Weekly | 18 (n = 124) |

14.5 | 15 | 12.8 | 33 (n = 241) |

13.7 | |

| More than once a week | 29 (n = 124) |

23.4 | 21 | 17.9 | 50 (n = 241) |

20.7 | |

| How do the palpitations start? | Suddenly | 104 (n = 123) |

84.6 | 94/116 | 81.0 | 198 (n = 239) |

82.8 |

| Gradually | 19 (n = 123) |

15.4 | 22/116 | 19.0 | 41 (n = 239) |

17.2 | |

| Can palpitations be provoked? | Yes | 16 (n = 123) |

13.0 | 18 (n = 116) |

15.5 | 34 (n = 239) |

14.2 |

| How do the palpitations end? | Suddenly | 48 (n = 121) |

39.7 | 47 (n = 115) |

40.9 | 95 (n = 236) |

40.3 |

| Gradually | 73 (n = 121) |

60.3 | 68 (n = 115) |

59.1 | 141 (n = 236) |

59.7 | |

| Participant able to end the attacks? | Yes | 19 (n = 123) |

15.4 | 14 | 12.0 | 33 (n = 240) |

13.8 |

| Recent alcohol use? | Yes | 11 | 8.8 | 16 | 13.7 | 27 | 11.2 |

| Recent cocaine or amphetamine use? | Yes | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Recent (last 7 days) febrile illness? | Yes | 9 | 7.2 | 8 | 6.8 | 17 | 7.0 |

| Past medical history | |||||||

| Previous or known hypertension/ischaemic/coronary/valvular heart disease/failure | Yes | 14 (n = 124) |

11.3 | 20 | 17.1 | 34 (n = 241) |

14.1 |

| Previous or known anaemia or thyrotoxicosis | Yes | 4 (n = 124) |

3.2 | 3 | 2.6 | 7 (n = 241) |

2.9 |

| Drug history – is the patient taking | |||||||

| β agonists | Yes | 7 | 5.6 | 8 | 6.8 | 15 | 6.2 |

| Antimuscarinics/Anticholinergic | Yes | 5 | 4.0 | 2 | 1.7 | 7 | 2.9 |

| Theophylline | Yes | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers | Yes | 3 | 2.4 | 6 | 5.1 | 9 | 3.7 |

| Class 1 anti-arrhythmics | Yes | 1 | 0.8 | 2 | 1.7 | 3 | 1.2 |

| Drugs that may prolong the QT interval | Yes | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.4 |

Table 3.

Examination findings, initial ECG and management.

| Data are n (%) unless stated. N = 242 (125/117) unless stated. Different denominators due to missing data | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention n = 125 |

Control n = 117 |

Total n = 242 |

|||||

| Examination | |||||||

| Initial pulse at triage /bpm - mean (SD) | 85.3 (19.4) (n = 124) |

83.0 (15.2) (n = 116) |

84.2 (17.5) (n = 240) |

||||

| Initial systolic BP at triage /mmHg - mean (SD) | 139.0 (22.5) (n = 124) |

139.0 (20.5) (n = 116) |

139.0 (21.5) (n = 240) |

||||

| Initial diastolic BP at triage /mmHg - mean (SD) | 83.8 (12.7) (n = 124) |

84.1 (13.6) (n = 116) |

83.9 (13.1) (n = 240) |

||||

| First postural difference if present /mmHg - mean (SD) | 6.7 (7.6) (n = 7) |

0.3 (0.8) (n = 6) |

3.8 (6.3) (n = 13) |

||||

| Admission ECG | |||||||

| Rate /bpm - mean (SD) | 78.8 (18.8) | 77.5 (16.1) | 78.2 (17.5) | ||||

| QRS axis - median (IQR) | 79.0 (39.0–88.0) (n = 117) |

80.0 (42.0–90.0) (n = 107) |

79.5 (40.5–89.0) (n = 224) |

||||

| QTc int /ms - mean (SD) | 395.1 (86.7) (n = 125) |

401.5 (47.3) (n = 114) |

398.2 (70.6) (n = 239) |

||||

| Sinus rhythm | 123 | 98.4 | 117 | 100.0 | 240 | 99.2 | |

| PR > 200 ms | 7 | 5.6 | 4 | 3.4 | 11 | 4.5 | |

| Slow risk in the initial portion of the QRS | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Heart block? | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| QRS duration ≥ 120 ms | 2 (n = 124) | 1.6 | 3 (n = 116) | 2.6 | 5 (n = 240) | 2.1 | |

| Number of ventricular ectopics | 0 | 118 (n = 124) | 95.2 | 115 (n = 116) | 99.1 | 233 (n = 240) | 97.1 |

| 1 | 4 (n = 124) | 3.2 | 1 (n = 116) | 0.9 | 5 (n = 240) | 2.1 | |

| 2 | 2 (n = 124) | 1.6 | 0 (n = 116) | 0.0 | 2 (n = 240) | 0.8 | |

| ED clinician rating of likelihood of any underlying cardiac arrhythmia | 1 | 14 (n = 121) | 11.6 | 23 (n = 116) | 19.8 | 37 (n = 237) | 15.6 |

| 2 | 18 (n = 121) | 14.9 | 12 (n = 116) | 10.3 | 30 (n = 237) | 12.7 | |

| 3 | 15 (n = 121) | 12.4 | 18 (n = 116) | 15.5 | 33 (n = 237) | 13.9 | |

| 4 | 15 (n = 121) | 12.4 | 17 (n = 116) | 14.7 | 32 (n = 237) | 13.9 | |

| 5 | 19 (n = 121) | 15.7 | 13 (n = 116) | 11.2 | 32 (n = 237) | 13.9 | |

| 6 | 13 (n = 121) | 10.7 | 14 (n = 116) | 12.1 | 27 (n = 237) | 11.4 | |

| 7 | 14 (n = 121) | 11.6 | 6 (n = 116) | 5.2 | 20 (n = 237) | 8.4 | |

| 8 | 10 (n = 121) | 8.3 | 8 (n = 116) | 6.9 | 18 (n = 237) | 7.6 | |

| 9 | 3 (n = 121) | 2.5 | 4 (n = 116) | 3.4 | 7 (n = 237) | 3.0 | |

| 10 | 0 (n = 121) | 0.0 | 1 (n = 116) | 0.9 | 1 (n = 237) | 0.4 | |

| Management | |||||||

| Participant discharged from the ED/AMU | 117 | 93.6 | 114 | 97.4 | 231 | 95.5 | |

| Participant referred to outpatients | 15 (n = 116) | 12.9 | 15 (n = 114) | 13.2 | 30 (n = 230) | 13.0 | |

| If admitted then where? | |||||||

| Ward - Non monitored | 3 (n = 8) | 37.5 | 2 (n = 3) | 66.7 | 5 (n = 11) | 45.5 | |

| Ward - Monitored | 0 (n = 8) | 0.0 | 0 (n = 3) | 0.0 | 0 (n = 3) | 0.0 | |

| Coronary Care Unit | 2 (n = 8) | 25.0 | 1 (n = 3) | 33.3 | 3 (n = 11) | 27.3 | |

| Direct to cardiology ward | 3 (n = 8) | 37.5 | 0 (n = 3) | 0.0 | 3 (n = 11) | 27.3 | |

| Reason(s) for admission? | |||||||

| Palpitation/pre-syncope investigation | 8 (n = 8) | 100.0 | 2 (n = 3) | 66.7 | 10 (n = 11) | 90.9 | |

| Other | 0 (n = 8) | 0.0 | 1 (n = 3) | 33.3 | 1 (n = 11) | 9.1 | |

A symptomatic rhythm was detected at 90 days in 69 (n = 124; 55.6%; 95% CI 46.9–64.4%) participants in the intervention group versus 11 (n = 116; 9.5%; 95% CI 4.2–14.8) in the control group (RR 5.9, 95% CI 3.3–10.5; p < 0.0001). A symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia was detected at 90 days in 11 (n = 124; 8.9%; 95% CI 3.9–13.9%) participants in the intervention group versus 1 (n = 116; 0.9%; 95% CI 0.0–2.5%) in the control group (RR 10.3, 95% CI 1.3–78.5; p = 0.006).

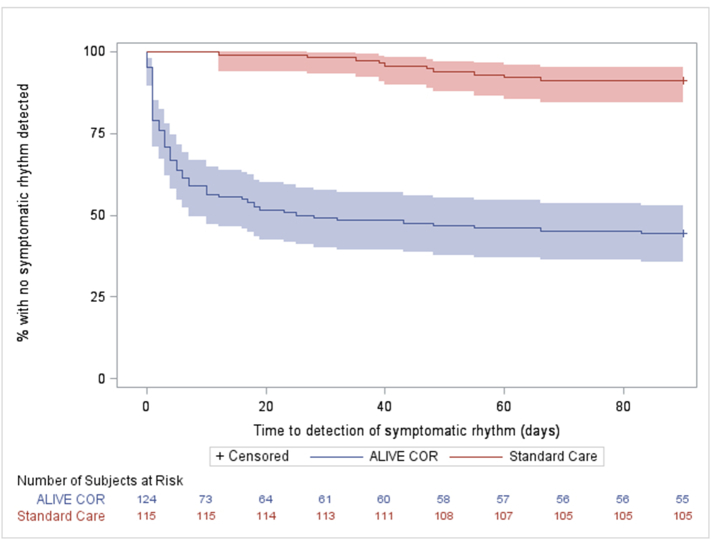

The mean time to symptomatic rhythm detection in the intervention group was 9.5 days (SD 16.1, range 0–83) versus 42.9 days (SD 16.0, range 12–66) in the standard care group (p < 0.0001). Fig. 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier curve of proportion of participants undiagnosed versus time up to 90 days for the intervention and control groups. Commonest symptomatic rhythms detected were sinus rhythm (in 53 participants; 66.3%), sinus tachycardia (19; 23.8%) and ectopic beats (13; 16.3%). Some participants had more than one symptomatic rhythm recorded. Eighty participants had a symptomatic rhythm detected with 12 of these having a symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation or flutter, SVT and sinus bradycardia) and 68 having sinus rhythm, sinus tachycardia or ectopics [Table 4]. There were four cases where the central cardiology team were required for further ECG opinion after review by both the central on call and trial team Emergency Physicians. Table 4 also details how the diagnosis was made in both groups.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve showing number of participants undiagnosed (y axis) versus time up to 90 days (x axis) in both study groups.

Table 4.

Summary of symptomatic rhythms, symptomatic cardiac arrhythmias and serious outcomes.

| N = 240 (124/116) unless stated. Different denominators due to missing data *some participants had more than one symptomatic rhythm recorded | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention n = 124 |

Control n = 116 |

Total n = 240 |

|

| Symptomatic rhythm* | 69 (55.6%) |

11 (9.5%) |

80 (33.3%) |

| Sinus rhythm (40–100) | 48 | 5 | 53 |

| Sinus tachycardia (> 100) | 12 | 7 | 19 |

| Ectopics | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| SVT | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Atrial flutter | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sinus bradycardia (< 40) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Atrial tachycardia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other rhythm | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Method of diagnosis of symptomatic rhythm* | |||

| AliveCor | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| 24-hour Holter | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| 48-hour Holter | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 7 + day Holter | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Subsequent ED visit ECG | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| GP visit ECG | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia* |

11 (8.9%) |

1 (0.9%) |

12 (5.0%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| SVT | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Sinus bradycardia (< 40) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Atrial flutter | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Serious outcome* |

11 (8.9%) |

2 (1.7%) |

13 (5.4%) |

| All cause death | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Major adverse cardiac events [MACE = myocardial infarction, life-threatening arrhythmia, insertion of a pacemaker or internal cardiac defibrillator, insertion of pacing wire] |

0 | 1 | 1 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| Significant structural heart disease | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Initiation of anti-arrhythmia medical therapy | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Life-threatening arrhythmia [ventricular tachyarrhythmia, complete or 3rd degree heart block, second degree heart block type II, pause > 6 s, symptomatic bradycardia < 40 beats per minute] |

0 | 0 | 1 |

The mean time to symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia detection in the intervention group was 9.9 days (SD 15.6, range 1–55) versus 48.0 days (1 participant) in the control group (p = 0.0004). Symptomatic cardiac arrhythmias were AF (8 intervention, 0 standard care), SVT (3 intervention, 0 standard care), sinus bradycardia (0 intervention, 1 standard care) and atrial flutter (1 intervention, 0 standard care).

Serious outcome at 90 days in the intervention group was 11 (8.9%) versus 2 (1.7%) in the control group (p = 0.02). At 90 days, 12 participants in the intervention group were subsequently undergoing (or planning to undergo) treatment for symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia versus 6 in the control group (p = 0.192). Table 5 details the results of the participant satisfaction and monitor compliance questionnaire. Eighty of 92 (87.0%) participants found the AliveCor monitor easy to use. There were more ED presentations (after index visit) due to palpitations/pre-syncope in the intervention group (12/124; 9.7%; 95% CI 4.5–14.9% with 1 or more non index ED presentations) compared to the control group (3/116; 2.6%; 95% CI 0.0–5.5%; p = 0.031). The only death in the study was in the intervention group in a participant known to have treated congenital structural heart disease whose death was thought unrelated to his initial presentation to the ED.

Table 5.

Results of the participant satisfaction and monitor compliance questionnaire.

| Intervention arm |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| Total | 125 | 100.0 | |

| The AliveCor heart monitor was easy to use | Missing | 33 | 26.4 |

| Strongly Disagree | 4 | 3.2 | |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | |

| Neutral | 8 | 6.4 | |

| Agree | 32 | 25.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 48 | 38.4 | |

| The AliveCor heart monitor was always available when I had symptoms and needed to record my heart tracing | Missing | 34 | 27.2 |

| Strongly Disagree | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Disagree | 9 | 7.2 | |

| Neutral | 14 | 11.2 | |

| Agree | 27 | 21.6 | |

| Strongly Agree | 39 | 31.2 | |

| I had no problems recording a heart tracing using the AliveCor app | Missing | 34 | 27.2 |

| Strongly Disagree | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Disagree | 5 | 4.0 | |

| Neutral | 16 | 12.8 | |

| Agree | 26 | 20.8 | |

| Strongly Agree | 41 | 32.8 | |

| I had no problems sending a heart tracing to the study team using the AliveCor app | Missing | 34 | 27.2 |

| Strongly Disagree | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Disagree | 5 | 4.0 | |

| Neutral | 25 | 20.0 | |

| Agree | 24 | 19.2 | |

| Strongly Agree | 35 | 28.0 | |

| During the study period (3 months) I was able to record a heart tracing when I had similar symptoms to the time I initially visited the Emergency Department | Missing | 34 | 27.2 |

| Strongly Disagree | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Disagree | 8 | 6.4 | |

| Neutral | 27 | 21.6 | |

| Agree | 28 | 22.4 | |

| Strongly Agree | 26 | 20.8 | |

| The AliveCor heart monitor will be useful in diagnosing the cause of my symptoms | Missing | 34 | 27.2 |

| Strongly Disagree | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Disagree | 6 | 4.8 | |

| Neutral | 33 | 26.4 | |

| Agree | 24 | 19.2 | |

| Strongly Agree | 27 | 21.6 | |

| Had you ever used a mobile heart tracing device before | Missing | 32 | 25.6 |

| Yes | 5 | 4.0 | |

| No | 88 | 70.4 | |

There was no difference in the number of participants with one or more inpatient hospital days (over all admissions) due to palpitations or pre-syncope in the intervention group (2; n = 122; 2 patients with no data; 1.6%; 95% CI 0.0–3.8%) compared to the control group (1; n = 116; 0.9%; 95% CI 0.0–2.5%; p > 0.999), number of outpatient presentations due to palpitations or pre-syncope (p = 0.058), number of GP presentations due to palpitations or pre-syncope (p = 0.312) or number of ECGs performed due to palpitations or pre-syncope (p = 0.143). Median overall healthcare utilisation cost (primary/community/secondary care and intervention costs) in the intervention group was £108 (IQR 99.0–246.50, range 99–2697) versus £0 in the standard care group (IQR 0–120.0, range 0–4161; p = 0.0001). Cost per symptomatic rhythm diagnosis was £921 less per patient per symptomatic rhythm in the intervention group (£474) compared to the control group (£1395).

7. Discussion

Use of a smartphone-based event recorder increases the symptom–rhythm correlation rate over five-fold at 90 days with a reduced cost per diagnosis. These are clinically significant rhythms as they diagnose the underlying cause of the patient's symptoms. In patients presenting with palpitations or near syncope the incorporation of a patient-activated detection device into routine practice may overcome some of the current difficulties in diagnosis caused by the normalisation of cardiac rhythm by the time the patient undergoes a clinical assessment. Given the frequency of patients presenting to the ED with palpitations and pre-syncope, our study findings suggest that a smartphone-based event recorder should be considered as part of on-going care of all patients presenting acutely with these symptoms.

There are different potential ways of incorporating the technology into patient care, which may depend on the configuration of local healthcare systems. In this study the devices and instructions were given to patients in the ED by a researcher, but this could also be undertaken at a follow-up appointment with a specialist nurse or family practitioner, where there is less time pressure than in emergency care. In this study, the ECGs were transmitted for central analysis; however, an alternative approach may be for the patient to show, on their phone, any recorded ECGs at a follow-up appointment. This would remove the need for the transfer of sensitive patient data and mean that a clinical system to respond to emailed ECGs would not be required. The AliveCor app rhythm analysis algorithm automatically reports any ECG recorded as normal, atrial fibrillation or unclassified with excellent sensitivity and specificity. Features such as this that are also found in other devices such as the newly launched Apple Watch Series 4 should allow ECG interpretation and patient education to be delivered at the time of ECG recording thereby reducing demand on physicians.

More patients had a subsequent ED attendance in the intervention group compared the control group. Whilst this number is small, it may be that the remote transmission of an ECG did not give the patient the immediate reassurance that they required. The psychology of patient interaction with ‘smart’ personal medical devices is an emerging field, and better understanding of patient/device interaction is likely to be important in realising the potential benefits of new technologies.

The patients found the monitor easy to use. This reinforces data from previous work in ED patients which showed that 74% found it acceptable to use a smartphone to monitor their health, 79% to use a medical device connecting to a smartphone to monitor their health, and 77% reported that they would feel confident to use such technology [27]. There is a concern that self-monitoring may lead to increased anxiety; however when the Arrhythmia Alliance [14] distributed AliveCor Heart Monitors to 1500 people of all ages, only one returned their monitor because it caused them to worry and check their heart rate too often.

We found that the commonest reason for a patient not to be able to participate was that they did not possess a smartphone. We did not record the age of non-participants, but it is likely that these were older patients. However, whilst smartphone ownership decreases with age our previous research shows 64% of those aged 50–75 and 30% over 75 years of age own a smartphone [27], and in the Arrhythmia Alliance study, older people were noted to be regular users of mobile technology and gave positive feedback about the system [14].

This study confirms previous evidence that most symptomatic rhythms in patients with palpitations or pre-syncope are benign [28]. Only 12 of 240 participants in the study experienced a symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia; the remaining 68 with symptomatic palpitations or pre-syncope were found to have sinus rhythm, sinus tachycardia or ectopic beats. Even in the absence of underlying arrhythmia, previously unexplained symptoms can cause anxiety and can have a significant impact on quality of life [29]. With such a low incidence of cardiac diagnoses in this population, it is perhaps appropriate that follow-up of these patients is in community care rather than in cardiology clinics (where currently these conditions account for up to one-fifth of all referrals) [30], [31], [32], [33], with only patients diagnosed with a symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia being referred to specialist care.

This study suggests that the AliveCor technology performs effectively and safely. The randomised, prospective design with systematic data collection is a key strength of the study. Whilst there was a potential variation in standard care between sites, this element of pragmatic design ensures our findings are generalisable across all types of standard care in the UK National Health Service without compromising validity. Potential limitations of our study include a large proportion of recruitment occurring in office hours largely by research staff in research active hospitals and the use of a central ECG reading service not available in routine practice.

Only one type of device was studied and many similar devices are entering the market. We think that the results of this study will be generalisable across many forms of patient-activated, symptom-based home ECG recording devices. Subtle differences in design or incorporation into clinical workflow may have an influence on effectiveness, so novel devices should undergo clinical evaluation. It is also possible that patients choosing to take part in a study of new technology may be more motivated to use the device, and it may not perform as well in a non-study setting.

In summary, this study demonstrates the ability of a smartphone-based event recorder to improve clinical care and patient experience for those suffering undiagnosed palpitations and pre-syncope. These findings are likely to be generalisable from Emergency Medicine to General/Internal/Acute Medicine and General (Family) Practice in a broad range of developed healthcare systems. A safe, non-invasive and easy to use smartphone-based event recorder should be considered part of on-going care of all patients presenting acutely with unexplained palpitations or pre-syncope.

Role of the Funding Source

The study was funded by Chest, Heart and Stroke Scotland (Action Research Grant R15/A164; £23,056) and British Heart Foundation (BHF Project Grant no. PG/17/63/33198; £21,347) which included funding for purchasing the devices. MR was supported by an NHS Research Scotland Career Researcher Clinician award. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests and no financial interest in the device used in this study. AliveCor had no involvement in the study.

Authors' Contributions

MR was responsible for the conception of the study. MR, NG, CL, ROB, KS and ST were responsible for the design of the study, ROB, MP, AG, MR, LK, FC, LJ, TH, GL, JG, JS and TC were responsible for acquisition of data, MR, ROB, NG, CL and ST were involved in data analysis and all authors were involved in interpretation of data, drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final submitted version and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

None.

Contributor Information

Matthew J. Reed, Email: matthew.reed@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Neil R. Grubb, Email: Neil.Grubb@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Christopher C. Lang, Email: Chris.Lang@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Rachel O'Brien, Email: Rachel.O'Brien@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Kirsty Simpson, Email: Kirsty.Simpson@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Mia Padarenga, Email: Mia.Padarenga@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Alison Grant, Email: Alison.Grant@nhslothian.scot.nhs.uk.

Sharon Tuck, Email: sharon.tuck@ed.ac.uk.

Liza Keating, Email: Liza.Keating@royalberkshire.nhs.uk.

Frank Coffey, Email: Frank.coffey@nottingham.ac.uk.

Lucy Jones, Email: ljones24@nhs.net.

Tim Harris, Email: Tim.Harris@bartshealth.nhs.uk.

Gavin Lloyd, Email: gavin.lloyd@nhs.net.

James Gagg, Email: James.Gagg@tst.nhs.uk.

Jason E. Smith, Email: jasonesmith@nhs.net.

Tim Coats, Email: tc61@leicester.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Thiruganasambandamoorthy V., Stiell I.G., Wells G.A., Vaidyanathan A., Mukarram M., Taljaard M. Outcomes in presyncope patients: a prospective cohort study. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(3):268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.452. [e6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Probst M.A., Mower W.R., Kanzaria H.K., Hoffman J.R., Buch E.F., Sun B.C. Analysis of emergency department visits for palpitations (from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey) Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(10):1685–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dimarco A.D., Onwordi E.N., Murphy C.F. Diagnostic utility of real-time smartphone ECG in the initial investigation of palpitations. Brit J Cardio. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blomstrom-Lundqvist C., Sheinman M.M., Aliot E.M. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias – executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raviele A., Giada F., Bergfeldt L. Management of patients with palpitations: a position paper from the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace. 2011;13:920–934. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE clinical knowledge summaries. Palpitations. London: NICE, May 2015. https://cks.nice.org.uk/palpitations#!topicsummary (accessed 16th August 2018).

- 7.Zimetbaum P.J., Josephson M.E. The evolving role of ambulatory arrhythmia monitoring in general practice. Ann Intern Med. 1999;150:848–856. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-10-199905180-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scherr D., Dalal D., Henrikson C.A. Prospective comparison of the diagnostic utility of a standard event monitor versus a ‘leadless’ portable ECG monitor in the evaluation of patients with palpitations. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2008;22:39–44. doi: 10.1007/s10840-008-9251-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zimetbaum P.J., Kim K.Y., Josephson M.E. Diagnostic yield and optimal duration of continuous-loop event monitoring for the diagnosis of palpitations. Ann Intern Med. 1998;28:890–895. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-11-199806010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett PM, Komatireddy R, Haaser S et al. Comparison of 24-hour Holter monitoring with 14-day novel adhesive patch electrocardiographic monitoring. Am J Med 2014; 127: 95.e11–95.e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Cheung CC1, Kerr CR, Krahn AD. Comparing 14-day adhesive patch with 24-h Holter monitoring. Future Cardiol. 2014; 10(3): 319–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Schreiber D., Sattar A., Drigalla D., Higgins S. Ambulatory cardiac monitoring for discharged emergency department patients with possible cardiac arrhythmias. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(2):194–198. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2013.11.18973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turakhia MP, Hoang DD, Zimetbaum P et al. Diagnostic utility of a novel leadless arrhythmia monitoring device. Am J Cardiol. 2013; 15; 112(4): 520–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. AliveCor heart monitor and AliveECG app (Kardia Mobile) for detecting atrial fibrillation. NICE advice MIB35. London: NICE, 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/mib35/chapter/technology-overview (accessed 16th August 2018).

- 15.William A.D., Kanbour M., Callahan T. Assessing the accuracy of an automated atrial fibrillation detection algorithm using smartphone technology: the iREAD study. Heart Rhythm. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lau J., Lowres N., Neubeck L. iPhone ECG application for community screening to detect silent atrial fibrillation: a novel technology to prevent stroke. Int J Cardiol. 2013;165:193–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.01.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowres N., Neubeck L., Salkeld G. Feasibility and cost-effectiveness of stroke prevention through community screening for atrial fibrillation using iPhone ECG in pharmacies. The SEARCHAF study. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:1167–1176. doi: 10.1160/TH14-03-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haberman Z.C., Jahn R.T., Bose R. Wireless smartphone ECG enables large-scale screening in diverse populations. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:520–526. doi: 10.1111/jce.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarakji K.G., Wazni O.M., Callahan T. Using a novel wireless system for monitoring patients after the atrial fibrillation ablation procedure: the iTransmit study. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desteghe L., Raymaekers Z., Lutin M. Performance of handheld electrocardiogram devices to detect atrial fibrillation in a cardiology and geriatric ward setting. Europace. 2017;19:29–39. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newham WG, Tayebjee MH. Excellent symptom rhythm correlation in patients with palpitations using a novel Smartphone based event recorder. J Atr Fibrillation 2017; 10(1): 1514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Macinnes M., Martin N., Fulton H., McLeod K.A. Comparison of a smartphone-based ECG recording system with a standard cardiac event monitor in the investigation of palpitations in children. Arch Dis Child. 2018 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-314901. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narasimha D., Hanna N., Beck H. Validation of a smartphone-based event recorder for arrhythmia detection. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;41(5):487–494. doi: 10.1111/pace.13317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell A.R.J., Le Page P. Living with the handheld ECG. BMJ Innov. 2015;1:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halcox J.P.J., Wareham K., Cardew A. Assessment of remote heart rhythm sampling using the AliveCor heart monitor to screen for atrial fibrillation: the REHEARSE-AF study. Circulation. 2017;136:1784–1794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed MJ, Grubb NR, Lang CC, et al. Multi-centre randomised controlled trial of a smart phone based event recorder alongside standard care versus standard care for patients presenting to the Emergency Department with palpitations and pre-syncope - the IPED (Investigation of Palpitations in the ED) study: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2018; 19: 711. nndoi: 10.1186/s13063-018-3098-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Summers A., Reed M.J. An evaluation of patient ownership and use and acceptability of smartphone technology within the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018;25(3):224–225. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber B.E., Kapoor W.H. Evaluations and outcomes of patients with palpitations. Am J Med. 1996;100:138–148. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)89451-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barsky A.J., Cleary P.D., Coeytaux R.R. The clinical course of palpitations in medical outpatients. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1782–1788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbott A.V. Diagnostic approach to palpitations. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:743–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messineo F.C. Ventricular ectopic activity: prevalence and risk. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:53J–56J. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)91200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K., Arrington M.E., Mangelsdorff A.D. The prevalence of symptoms in medical outpatients and the adequacy of therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1685–1689. doi: 10.1001/archinte.150.8.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knudson M.P. The natural history of palpitations in a family practice. J Fam Pract. 1987;24:357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.