Abstract

BACKGROUND

Understanding sexual risk among youth can inform the design of effective HIV prevention interventions.

METHODS

The 2012 Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey was a nationally representative population-based survey. We administered a questionnaire and collected blood samples for HIV testing. We examined factors associated with unsafe sex among unmarried youth aged 15–19 and 20–24 years.

RESULTS

Of 2,090 unmarried youth aged 15–19 years, 33.3% (95% confidence interval [CI] 30.6–36.1) had ever had sex. Among those, 66.0% (95% CI 61.3–70.7) had sex in the past year (sexually active), and of these, 38.7% (95% 33.4 –44.0) reported unsafe sex. No differences were observed in unsafe sex by sex. Factors associated with increased adjusted odds of unsafe sex among youth aged 15–19 years were residence in Central province; having primary or lower education; sexual debut before age 15 years; ever receiving money, gifts or favours for sex (transactional sex); multiple sexual partners in the past year; and low self-perceived risk of HIV. Of the 1,079 unmarried youth aged 20–24 years, 77.2% (95% CI 74.2–80.2) had ever had sex. Of these, 73.1% (95% CI69.8–76.3) were sexually active, and 24.1% (95% CI 18.1–30.1) of women and 31.9% (95% CI 26.4–37.5) of men reported unsafe sex in the past year. Factors associated with increased adjusted odds of unsafe sex among youth aged 20–24 years were primary or lower education, transactional sex and multiple partners in the past year.

CONCLUSION

Unsafe sex is common among Kenyan youth, especially those aged 15–19 years. HIV prevention efforts need to target youth, support educational progression and economic empowerment.

Keywords: Unsafe sex, youth, HIV, population-based survey, Kenya

BACKGROUND

A key objective of the global response to HIV is to prevent new HIV infections. It is estimated that young people aged 15–24 years account for 40% of new HIV infections among individuals aged 15 years and above (World Health Organization-WPRO, 2015). In 2013, there were 250,000 new HIV infections among adolescents with two-thirds occurring among adolescent girls (Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS, 2015).

Most of the sexual behaviours that put individuals at risk for HIV are initiated during adolescence or young adulthood, highlighting the important role of young persons in the HIV epidemic. Interventions that target risky sexual behaviours among youth form a critical component of national strategies to prevent HIV among young people in sub-Saharan Africa (Stockl, Karla, Jacobi, & Watts, 2013; Doyle, Mavedzenge, Plummer, & Ross, 2012; Rositich, Cherutich, Brentlinger, Kiarie, Nduati, & Farquhar, 2012; Pettifor, O’Brien, Macphail, Miller, & Rees, 2009). In addition, global initiatives, such as the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief DREAMS Initiative, have recently focused on addressing the factors that influence HIV behavioural risk among girls and young women as an essential component in controlling the HIV epidemic (United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, n.d.). With 70% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa under the age of 30 years as of 2010 (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa & United Nations Programme on Youth, n.d.), targeting the HIV prevention response to youth will be key to curbing the epidemic in the region.

While there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of behavioural interventions among youth (Michielsen, 2012; Michielsen, Chersich, Luchters, Ronan Van Rossem, & Temmerman, 2010), carefully designed school– and community-based behavioural interventions can promote safer sexual behaviours (Chin, Sipe, Elder, Mercer, Chat–topadhyay, Jacob, et al., 2009; Crepaz, Marshall, Aupont, Jacobs, Mizuno, Kay, et al., 2009; Darbes, Crepaz, Lyles, Kennedy, & Rutherford, 2008; Kirby, Obasi, & Laris, 2006; Gallant, & Maticka-Tyndale, 2004). Participation in school-based sex education and HIV prevention programmes has been associated with delayed sexual debut especially among girls, reduced pregnancy rates and lowered the frequency of risky sexual behaviours (Coates, Richter, & Caceres, 2008; Kirby, 2002). Additionally, there is evidence that keeping girls in school reduces risky sexual behaviours and the risk of getting HIV infection (Pettifor, Levandowski, MacPhail, Padian, Cohen, & Rees, 2008).

In Kenya, behaviour change interventions for unmarried and non-cohabiting youth primarily focus on sexual abstinence, delaying sexual debut, correct and consistent condom use, reduction of multiple sexual partners, and promoting effective parent–child communication on sexuality and high–risk sexual behaviours (Kenya Ministry of Health, n.d.). However, the impact of such programmes in behaviour change modification among young people has not been measured systematically. Nationally representative data on the frequency and trend in sexual behaviours of young people can provide insight on the effectiveness of youth behaviour change interventions and considerations for future targeted programmes for this population.

In 2012–2013, Kenya conducted a second AIDS Indicator Survey (KAIS 2012) to provide nationally representative population-based data to inform strategies for the national response on HIV prevention, care and treatment for the Kenyan population (National AIDS/STIControl Program, 2013). This paper describes the sexual behaviours of unmarried and non-cohabiting young people aged 15–24 years participating in the KAIS 2012, describes differences in sexual behaviours as measured in the first and second Kenya AIDS Indicator Surveys (National AIDS/STI Control Program, 2009; 2013) and examines factors associated with unsafe sex in this sub-population.

METHODS

Study design

KAIS 2012 was a nationally representative cross-sectional population-based survey of persons aged 18 months to 64 years. A two-stage cluster sampling design provided representative estimates of HIV-related indicators. In the first stage, clusters were randomly sampled from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics national household sampling frame; in the second stage, 25 households were selected using systematic probability sampling. Eligible households and persons within these households who met the inclusion criteria were selected to participate in the survey. The detailed methods of this study are described elsewhere (Waruiru, Kim, Kimanga, Ng’ang’a, Schwarcz, Kimondo, et al., 2012). In this paper, we restrict our analysis to unmarried non-cohabiting young people aged 15–24 years.

Data collection procedures

A standardized questionnaire was administered to young people aged 15–24 years. The questionnaire collected information on socio-demographic characteristics; age at sexual debut; knowledge about where to get condoms; sexual activity in the past year; sexual partners including number of lifetime sexual partners; condom use with sexual partners; knowledge of HIV status of sexual partners; sex in exchange for favours, gifts or money; HIV testing behaviour; and male circumcision. Participants provided a blood sample for HIV testing at a central laboratory and were offered home-based testing and counselling to learn their HIV status using a rapid HIV testing algorithm based on national guidelines (NASCOP, 2010).

Measurements

A wealth index variable served as a measure of household wealth based on household characteristics (Rutstein & Johnson, 2004). Early sexual debut was defined as first sexual intercourse before the age of 15 years. Respondents who reported having had sex in the last 12 months were defined as being sexually active. Respondents who had ever had sex were asked if they knew the HIV status of their sexual partners in the past 12 months. If they knew the HIV status of their partners, they were asked to disclose their partner’s HIV status. Those who self-reported unprotected sexual intercourse with a partner of unknown or known sero–discordant HIV status (based on respondent’s laboratory confirmed HIV test result and self-reported partner HIV status) were considered to have engaged in unsafe sex.

Statistical analysis

We stratified our analysis by two age groups, 15–19 years and 20–24 years. We conducted univariate analysis to describe socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify socio-demographic, behavioural, and biologic factors associated with unsafe sex. The multivariate models included variables associated with unsafe sex in the bivariate analyses at a p–value < 0.25 and other variables that were potential confounders or were known to be associated with unsafe sex. We present proportions, odds ratios (OR), adjusted odds ratios (AOR), and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Variables that remained in the models at a p–value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. We also assessed temporal changes in select sexual behaviours based on data from the KAIS 2007 and KAIS 2012. Z–tests were conducted to test for statistical significance (defined as p–value < 0.05) in differences observed between young people in the two age groups in the two surveys. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) and took into account stratification and clustering in the survey design. Estimates were weighted to account for sampling probability and adjusted for survey non-response.

Ethical considerations

The KAIS 2012 protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Kenya Medical Research Institute and the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and by the Committee on Human Research of the University of California, San Francisco. For those aged 15–17 years, parental/guardian consent and minor assent were obtained before administering the questionnaire. Young people aged less than 18 years who were pregnant, married, or had children were regarded as mature minors and provided their own informed consent, as did those aged 18–24 years. Survey staff were trained on how to refer young people for counselling services and the importance of maintaining confidentiality.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics

There were 4,541 youth aged 15–24 years who completed interviews and of these, 2,292 were aged 15–19 years, and 2,249 were aged 20–24 years. Among those 15–24 years old, 3,169 (72.0%, 95% CI 69.9–74.2) had never been married or cohabited with a partner. Of the 2,292 young people aged 15–19 years who completed interviews, 2,090 (92.3%, 95% CI 90.8–93.8) had never been married or cohabited with a partner, and of these 1,032 (43.0%, 95% CI 40.3–45.7) were females and 1,466 (71.1%, 95% CI 67.1–75.1) resided in rural areas (Table 1). Over forty percent had either completed primary or secondary education.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and sexual characteristics of never married, non-cohabiting youth aged 15–19 years by sex, KAIS 2012 (N=2,090)

| Variable | N | Total† weighted % (95% CI) | n | Male weighted % (95% CI) | n | Female weighted % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 1466 | 71.1 (67.1 – 75.1) | 753 | 72.4 (68.0 – 76.8) | 713 | 69.4 (64.2 – 74.5) |

| Urban | 624 | 28.9 (24.9 – 32.9) | 305 | 27.6 (23.2 – 32.0) | 319 | 30.6 (25.5 – 35.8) |

| Region | ||||||

| Nairobi | 204 | 8.3 (6.6 – 10.1) | 95 | 7.7 (5.8 – 9.6) | 109 | 9.2 (6.7 –11.7) |

| Central | 194 | 10.3 (8.1 – 12.5) | 95 | 10.0 (7.3 – 12.6) | 99 | 10.8 (8.0 – 13.5) |

| Coast | 229 | 8.2 (5.8 – 10.5) | 107 | 7.5 (5.3 – 9.6) | 122 | 9.1 (5.9 – 12.3) |

| Eastern | 406 | 14.0 (11.1 – 16.9) | 216 | 14.5 (10.9 – 18.0) | 190 | 13.4 (10.5 – 16.3) |

| Nyanza | 312 | 15.8 (12.9 – 18.6) | 171 | 16.6 (12.8 – 20.4) | 141 | 14.7 (11.8 – 17.6) |

| Rift Valley | 416 | 29.7 (24.8 – 34.6) | 213 | 30.5 (24.8 – 36.2) | 203 | 28.6 (23.0 – 34.2) |

| Western | 329 | 13.7 (11.0 – 16.4) | 161 | 13.3 (9.7 – 16.8) | 168 | 14.3 (11.6 – 17.0) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| No primary | 55 | 1.3 (0.6–1.9) | 29 | 1.0 (0.4 – 1.7) | 26 | 1.6 (0.6–2.7) |

| Incomplete primary | 369 | 15.0 (12.7 – 17.3) | 185 | 14.7 (11.4 – 18.0) | 184 | 15.4 (12.3 – 18.5) |

| Complete primary | 875 | 41.7(38.9–44.5) | 456 | 43.3 (39.4 – 47.2) | 419 | 39.5 (35.3 – 43.7) |

| Secondary+ | 791 | 42.0 (38.4 – 45.7) | 388 | 41.0 (36.2 – 45.8) | 403 | 43.4 (38.3 – 48.5) |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Lowest | 506 | 23.4 (19.6 – 27.1) | 274 | 24.8 (20.1 – 29.5) | 232 | 21.4 (17.7–25.1) |

| Second | 531 | 25.8(22.5 – 29.1) | 288 | 27.6(23.7 – 31.6) | 243 | 23.3 (19.6 – 27.1) |

| Middle | 395 | 18.6 (16.0 – 21.2) | 184 | 17.0 (14.0 – 19.9) | 211 | 20.7 (17.4 – 24.1) |

| Fourth | 318 | 15.5 (12.6 – 18.3) | 163 | 15.9 (12.3 – 19.4) | 155 | 15.0 (11.9 – 18.0) |

| Highest | 340 | 16.8 (13.0 – 20.5) | 149 | 14.7 (11.0 – 18.3) | 191 | 19.5 (14.5 – 24.5) |

| Circumcised | ||||||

| Yes | 900 | 85.0 (82.3 – 87.8) | 900 | 85.0 (82.3 – 87.8) | - | - |

| No | 154 | 15.0 (12.2 – 17.7) | 154 | 15.0 (12.2 – 17.7) | - | - |

| Religion | ||||||

| Catholic | 430 | 21.4 (18.5–24.4) | 216 | 21.5 (18.0 – 24.9) | 214 | 21.3 (17.6–25.1) |

| Protestant | 1347 | 68.5 (64.9 – 72.1) | 659 | 67.5 (63.3 – 71.7) | 688 | 69.8 (64.9 – 74.7) |

| Muslim | 234 | 6.6 (4.2 – 8.9) | 126 | 6.1 (3.9 – 8.3) | 108 | 7.2 (2.9 – 11.4) |

| None | 47 | 2.5 (1.3 – 3.7) | 35 | 3.6 (1.7–5.6) | 12 | 1.0 (0.3 – 1.7) |

| Other | 32 | 1.0 (0.4 – 1.7) | 22 | 1.3 (0.3 – 2.2) | 10 | 0.7 (0.2 – 1.3) |

| Ever had sex | ||||||

| No | 1451 | 66.7 (63.9 – 69.4) | 679 | 62.1 (58.4 – 65.8) | 772 | 72.7 (69.3 – 76.2) |

| Yes | 635 | 33.3 (30.6 – 36.1) | 377 | 37.9 (34.2 – 41.6) | 258 | 27.3 (23.8 – 30.7) |

| Early sexual debut | ||||||

| No | 417 | 65.5 (60.8 – 70.2) | 228 | 60.3 (54.2 – 66.5) | 189 | 75.1 (69.1 – 81.0) |

| Yes | 209 | 34.5 (29.8 – 39.2) | 144 | 39.7 (33.5 – 45.8) | 65 | 24.9 (19.0 – 30.9) |

| Ever tested for HIV* | ||||||

| No | 226 | 38.0 (33.3 – 42.8) | 161 | 44.8 (38.4 – 51.2) | 65 | 25.6(19.5 – 31.6) |

| Yes | 409 | 62.0 (57.2 – 66.7) | 216 | 55.2 (48.8 – 61.6) | 193 | 74.4 (68.4 – 80.5) |

| Knows where to get a condom* | ||||||

| No | 99 | 13.9 (11.2 – 16.7) | 34 | 8.9 (5.8 – 12.1) | 65 | 23.2 (18.0 – 28.4) |

| Yes | 536 | 86.1 (83.3 – 88.8) | 343 | 91.1 (87.9 – 94.2) | 193 | 76.8 (71.6 – 82.0) |

| Used a condom at first sex* | ||||||

| No | 333 | 54.5(49.9–59.1) | 205 | 57.5 (51.4 – 63.7) | 128 | 48.8(41.7–56.0) |

| Yes | 302 | 45.5(40.9–50.1) | 172 | 42.5 (36.4 – 48.5) | 130 | 51.2 (44.0 – 58.3) |

| Ever received money, gifts or favours for sex* | ||||||

| No | 390 | 92.1 (89.5 – 94.8) | 234 | 94.3 (91.4 – 97.3) | 156 | 88.2 (82.7 – 93.6) |

| Yes | 33 | 7.9 (5.2 – 10.5) | 15 | 5.7 (2.7 – 8.6) | 18 | 11.8 (6.4 – 17.3) |

| Sexually active in the past year* | ||||||

| No | 212 | 34.0 (29.3 – 38.7) | 128 | 34.7 (28.9 – 40.5) | 84 | 32.7 (26.1 – 39.3) |

| Yes | 423 | 66.0 (61.3 – 70.7) | 249 | 65.3 (59.5 – 71.1) | 174 | 67.3 (60.7 – 73.9) |

| Tested for HIV in the last year** | ||||||

| No | 231 | 56.8 (51.1 – 62.5) | 156 | 63.7 (55.8 – 71.7) | 75 | 44.4 (37.0 – 51.9) |

| Yes | 192 | 43.2 (37.5 – 48.9) | 93 | 36.3 (28.3 – 44.2) | 99 | 55.6 (48.1 – 63.0) |

| Had multiple (2+) sex partners in past year** | ||||||

| No | 358 | 83.6 (79.7 – 87.4) | 194 | 77.7 (72.2 – 83.1) | 164 | 94.0 (90.2 – 97.8) |

| Yes | 62 | 16.4 (12.6 – 20.3) | 52 | 22.3 (16.9 – 27.8) | 10 | 6.0 (2.2 – 9.9) |

| Knew HIV status of sexual partners in the past year** | ||||||

| No | 274 | 66.7 (61.9 – 71.6) | 187 | 75.9 (69.9 – 81.8) | 87 | 50.5 (42.5 – 58.6) |

| Yes | 146 | 33.3 (28.4 – 38.1) | 59 | 24.1 (18.2 – 30.1) | 87 | 49.5(41.4–57.5) |

| Consistent condom use in past year** | ||||||

| No | 237 | 56.7 (51.2 – 62.3) | 125 | 52.1 (44.5 – 59.7) | 112 | 65.0 (57.3 – 72.7) |

| Yes | 183 | 43.3 (37.7–48.8) | 121 | 47.9 (40.3 – 55.5) | 62 | 35.0 (27.3 – 42.7) |

| Had unsafe sex in the past year** | ||||||

| No | 264 | 61.3(56.0–66.6) | 156 | 61.5 (54.0 – 69.0) | 108 | 61.0 (53.0 – 69.0) |

| Yes | 159 | 38.7 (33.4 – 44.0) | 93 | 38.5 (30.9 – 47.1) | 66 | 39.0(31.1–47.0) |

| Use condom with last sexual partner in past year** | ||||||

| No | 228 | 54.7 (49.0 – 60.5) | 119 | 49.7 (42.1 – 57.3) | 109 | 63.8 (56.0 – 71.5) |

| Yes | 191 | 45.3 (39.5 – 51.0) | 127 | 50.3 (42.7 – 57.9) | 64 | 36.2 (28.5 – 44.0) |

| Illicit drug use in past year | ||||||

| No | 1922 | 91.2 (89.2 – 93.2) | 916 | 86.4 (83.0 – 89.7) | 1006 | 97.6 (96.5 – 98.7) |

| Yes | 168 | 8.8 (6.8 – 10.8) | 142 | 13.6 (10.3 – 17.0) | 26 | 2.4 (1.3 – 3.5) |

| Self–perception of HIV risk*** | ||||||

| No risk | 41 | 34.8 (25.0 – 44.6) | 26 | 38.8 (26.2 – 51.3) | 15 | 26.9 (13.8 – 40.1) |

| Low risk | 49 | 36.9 (26.1 – 47.7) | 30 | 34.4 (21.8 – 47.1) | 19 | 41.9 (27.2 – 56.6) |

| Moderate risk | 22 | 15.6 (9.1 – 22.2) | 10 | 12.7(5.1 – 20.3) | 12 | 21.5 (9.8 – 33.2) |

| High risk | 18 | 12.6 (6.5 – 18.7) | 13 | 14.1 (6.5 – 21.7) | 5 | 9.7 (1.3 – 18.0) |

Among youth who had ever had sex.

Among youth who were sexually active in the past year.

Among sexually active youth who reported unsafe sex in the past year.

Due to missing responses, totals vary between variables.

Of the 2,249 respondents aged 20–24 years who completed interviews, 1,079 (51.2%, 95% CI 48.2–54.2) had never been married or cohabited with a partner. Of these, 431 (33.7%, 95% CI 30.2–37.1) were females and 53.3% (95% CI 48.5–58.0) resided in rural areas while 70.5% (95% CI 66.8–74.1) had completed secondary education (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic and sexual characteristics of never married, non-cohabiting youth aged 20–24 years by sex, KAIS 2012 (N=1079)

| Variable | N | Total† weighted % (95% CI) | n | Male weighted % (95% CI) | n | Female weighted % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 564 | 53.3 (48.5 – 58.1) | 360 | 55.3 (49.7–61.0) | 204 | 49.2 (42.6 – 55.8) |

| Urban | 515 | 46.7 (41.9 – 51.5) | 288 | 44.7 (39.0 – 50.3) | 227 | 50.8 (44.2 – 57.4) |

| Region | ||||||

| Nairobi | 219 | 16.7 (13.6 – 19.8) | 110 | 14.7 (11.4 – 18.0) | 109 | 20.6 (15.7 – 25.5) |

| Central | 98 | 10.2 (7.7 – 12.7) | 60 | 10.3 (7.4 – 13.2) | 38 | 10.0 (6.0 – 13.9) |

| Coast | 125 | 9.5 (7.0 – 11.9) | 84 | 10.3 (7.4 – 13.1) | 41 | 8.0(4.7 –11.3) |

| Eastern | 206 | 16.1 (13.0 – 19.3) | 143 | 17.1 (13.2 –21.0) | 63 | 14.2 (10.4 – 18.0) |

| Nyanza | 116 | 10.9 (8.2 – 13.5) | 64 | 10.3 (7.0 – 13.6) | 52 | 12.0 (8.5 – 15.6) |

| Rift Valley | 209 | 28.1 (23.0 – 33.1) | 129 | 29.6 (23.6 – 35.7) | 80 | 24.9 (18.0 –31.8) |

| Western | 106 | 8.6 (6.4 – 10.8) | 58 | 7.8 (5.2 – 10.4) | 48 | 10.3 (6.8 – 13.9) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| No primary | 33 | 1.4 (0.5 –2.3) | 23 | 1.0 (0.2 – 1.9) | 10 | 2.1 (0.6 – 3.6) |

| Incomplete primary | 52 | 3.8 (2.5 – 5.1) | 30 | 3.1 (1.6 – 4.6) | 22 | 5.3 (2.9 – 7.7) |

| Complete primary | 267 | 24.3 (21.0 – 27.6) | 176 | 25.6(21.6 – 29.7) | 91 | 21.6 (16.8–26.4) |

| Secondary+ | 727 | 70.5 (66.8 – 74.1) | 419 | 70.2 (65.8 – 74.7) | 308 | 71.0 (65.8 – 76.1) |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Lowest | 182 | 15.8 (12.1 – 19.5) | 133 | 18.3 (13.4 – 23.2) | 49 | 10.8 (7.4 – 14.3) |

| Second | 154 | 15.1 (11.9 – 18.3) | 91 | 15.3 (11.3 – 19.3) | 63 | 14.7 (10.7 – 18.7) |

| Middle | 182 | 16.5 (13.4 – 19.6) | 114 | 17.3 (13.3 – 21.3) | 68 | 14.9 (10.9 – 19.0) |

| Fourth | 251 | 23.3 (19.2 – 27.4) | 155 | 23.1 (18.6 – 27.7) | 96 | 23.6 (17.3 – 29.9) |

| Highest | 310 | 29.3 (24.6 – 34.1) | 155 | 26.0(20.6 – 31.3) | 155 | 36.0 (29.6 – 42.4) |

| Circumcised | ||||||

| Yes | 602 | 93.2 (90.7 – 95.6) | 602 | 93.2 (90.7 – 95.6) | - | - |

| No | 43 | 6.8 (4.4 – 9.3) | 43 | 6.8 (4.4 – 9.3) | - | - |

| Religion | ||||||

| Catholic | 281 | 26.7 (23.0 – 30.4) | 155 | 24.5 (20.3 – 28.6) | 126 | 31.1 (24.7 – 37.5) |

| Protestant | 655 | 63.8 (59.9 – 67.7) | 379 | 64.1 (59.7 – 68.6) | 276 | 63.2 (56.8 – 69.6) |

| Muslim | 98 | 5.5 (3.5 – 7.6) | 77 | 6.3 (4.0 – 8.5) | 21 | 4.1 (1.6 – 6.6) |

| None | 33 | 3.4 (1.9 – 4.8) | 28 | 4.6 (2.6 – 6.7) | 5 | 0.9 (0.0 – 1.7) |

| Other | 12 | 0.6 (0.1 – 1.1) | 9 | 0.5 (0.0 – 1.1) | 3 | 0.7 (0.0 – 1.5) |

| Ever had sex | ||||||

| No | 269 | 22.8 (19.8 – 25.8) | 141 | 19.5 (15.7 – 23.4) | 128 | 29.3 (24.2 – 34.5) |

| Yes | 805 | 77.2 (74.2 – 80.2) | 505 | 80.5 (76.6 – 84.3) | 300 | 70.7 (65.5 – 75.8) |

| Early sexual debut | ||||||

| No | 675 | 84.9 (81.8 – 88.1) | 409 | 82.0 (77.9 – 86.1) | 266 | 91.5 (87.9 – 95.1) |

| Yes | 108 | 15.1 (11.9 – 18.2) | 84 | 18.0(13.9 – 22.1) | 24 | 8.5 (4.9 – 12.1) |

| Ever tested for HIV* | ||||||

| No | 193 | 24.8 (21.0 – 28.6) | 154 | 30.4 (25.6 – 35.3) | 39 | 12.2 (8.2 – 16.2) |

| Yes | 610 | 75.2 (71.4 – 79.0) | 349 | 69.6 (64.7 – 74.4) | 261 | 87.8 (83.8 – 91.8) |

| Knows where to get a condom* | ||||||

| No | 51 | 4.7 (3.3 – 6.2) | 21 | 3.0 (1.5 – 4.4) | 30 | 8.7 (5.2 – 12.2) |

| Yes | 754 | 95.3 (93.8 – 96.7) | 484 | 97.0 (95.6 – 98.5) | 270 | 91.3 (87.8 – 94.8) |

| Used a condom at first sex* | ||||||

| No | 395 | 50.5 (46.5 – 54.6) | 255 | 52.3 (46.9 – 57.7) | 140 | 46.6 (40.5 – 52.6) |

| Yes | 410 | 49.5 (45.4 – 53.5) | 250 | 47.7 (42.3 – 53.1) | 160 | 53.4 (47.4 – 59.5) |

| Ever received money, gifts or favours for sex* | ||||||

| No | 549 | 94.8 (92.9 – 96.7) | 352 | 97.0 (95.2 – 98.7) | 197 | 90.1 (85.4 – 94.7) |

| Yes | 33 | 5.2 (3.3 – 7.1) | 14 | 3.0 (1.3 – 4.8) | 19 | 9.9 (5.3 – 14.6) |

| Sexually active in the past year* | ||||||

| No | 223 | 26.9 (23.7 – 30.2) | 139 | 27.2 (22.8 – 31.6) | 84 | 26.3 (21.1 – 31.5) |

| Yes | 582 | 73.1 (69.8 – 76.3) | 366 | 72.8 (68.4 – 77.2) | 216 | 73.7 (68.6 – 78.8) |

| Tested for HIV in the last year** | ||||||

| No | 278 | 48.8 (44.6 – 53.1) | 194 | 53.0 (47.6 – 58.3) | 84 | 39.7 (32.5 – 46.8) |

| Yes | 304 | 51.2 (46.9 – 55.4) | 172 | 47.0(41.7 – 52.4) | 132 | 60.3 (53.2 – 67.5) |

| Had multiple (2+) sex partners in past year** | ||||||

| No | 474 | 82.7 (79.2 – 86.2) | 274 | 77.8 (72.9 – 82.6) | 200 | 93.6 (90.0 – 97.3) |

| Yes | 98 | 17.3 (13.8 – 20.8) | 85 | 22.2 (17.4 – 27.1) | 13 | 6.4 (2.7 – 10.0) |

| Knew HIV status of sexual partners in the past year** | ||||||

| No | 317 | 56.6 (52.2 – 61.1) | 233 | 64.6 (59.1 – 70.1) | 84 | 38.9(31.9 – 45.9) |

| Yes | 255 | 43.4 (38.9 – 47.8) | 126 | 35.4 (29.9 – 40.9) | 129 | 61.1 (54.1 – 68.1) |

| Consistent condom use in past year** | ||||||

| No | 338 | 57.6 (53.4 – 61.9) | 159 | 44.9 (39.2 – 50.5) | 75 | 36.8 (30.1 – 43.4) |

| Yes | 234 | 42.4 (38.1 – 46.6) | 159 | 44.9 (39.2 – 50.5) | 75 | 36.8 (30.1 – 43.4) |

| Had unsafe sex in the past year** | ||||||

| No | 412 | 70.5 (66.4 – 74.7) | 246 | 68.1 (62.5 – 73.6) | 166 | 75.9 (69.9 – 81.9) |

| Yes | 170 | 29.5 (25.3 – 33.6) | 120 | 31.9 (26.4 – 37.5) | 50 | 24.1 (18.1 – 30.1) |

| Use condom with last sexual partner in past year** | ||||||

| No | 299 | 50.9 (46.6 – 55.2) | 167 | 46.0 (40.3 – 51.6) | 132 | 61.9 (55.1 – 68.8) |

| Yes | 264 | 49.1 (44.8 – 53.4) | 188 | 54.0 (48.4 – 59.7) | 76 | 38.1 (31.2 – 44.9) |

| Illicit drug use in past year | ||||||

| No | 835 | 76.2 (73.0 – 79.4) | 427 | 66.9 (62.5 – 71.2) | 408 | 94.6 (92.2 – 97.0) |

| Yes | 244 | 23.8 (20.6 – 27.0) | 221 | 33.1 (28.8 – 37.5) | 23 | 5.4 (3.0 – 7.8) |

| Self–perception of HIV risk*** | ||||||

| No risk | 40 | 24.9 (16.3 – 33.5) | 28 | 23.1 (12.7 – 33.5) | 12 | 30.4 (16.0 – 44.8) |

| Low risk | 75 | 48.8(39.7 – 57.9) | 51 | 47.9 (36.9 – 58.9) | 24 | 51.5 (35.5 – 67.5) |

| Moderate risk | 26 | 16.0 (9.6 – 22.3) | 20 | 16.9 (9.4 – 24.4) | 6 | 13.1 (3.0 – 23.2) |

| High risk | 15 | 10.4 (5.1 – 15.6) | 13 | 12.1 (5.5 – 18.7) | 2 | 5.1 (0.0 – 11.9) |

Among youth who had ever had sex.

Among youth who were sexually active in the past year.

Among sexually active youth who reported unsafe sex in the past year.

Due to missing responses, totals vary between variables.

Sexual behaviours of young people aged 15–19 years

Among those aged 15–19 years, males (37.9%, 95% CI34.2–41.6) were more likely than females (27.3%, 95% CI23.8–30.7) to have ever had sex (Table 1). Males (39.7%, 95% CI 33.5–45.8) were also more likely than their female counterparts (24.9%, 95% CI 19.0–30.9) to report early sexual debut.

Among those who had ever had sex, 66.0% (95% CI61.3–70.7) were sexually active in the past year. Of these,22.3% (95% CI 16.9–27.8) of males and 6.0% (95% CI 2.2–9.9) of females reported two or more sexual partners in the past year. A majority of sexually active males (75.9%, 95% CI 69.9–81.8) and 50.5% (95% CI 42.5–58.6) of females did not know the HIV status of their sexual partners.

Fewer females (76.8%, 95% CI 71.6–82.0) knew where to get a condom than males (91.1%, 95% CI 87.9–94.2). Among those who were sexually active, only 35.0% (95% CI 27.3–42.7) of females and 47.9% (95% CI 40.3–55.5) of males used condoms consistently with their sexual partners in the past year, and 39.0% (95% CI 31.1–47.0) of females and 38.5% (95% CI 30.9–47.1) of males engaged in unsafe sex in the past year. Overall, 5.7% (95% CI 2.7–8.6) of males and 11.8% of females (95% CI 6.4–17.3) who ever had sex had received money, gifts, or favors in exchange for sex in the past.

More females (74.4%, 95% CI 68.4–80.5) had ever been tested for HIV than males (55.2%, 95% CI 48.8–61.6), and among those who were sexually active, females (55.6%, 95% CI 48.1–63.0) were also more likely than males (36.3%, 95% CI 28.3–44.2) to have had an HIV test in the past year.

After controlling for select demographic, behavioural, and biological variables, residing in Central province (AOR 3.58; 95% CI 1.01–12.75); reporting primary education or lower compared to higher level of education (AOR 4.11, 95% CI 2.12–7.96); early sexual debut (AOR1.95, 95% CI 1.03–3.69); having ever received money, gifts or favours in exchange for sex (AOR 3.04, 95% CI 1.11–8.33); having multiple sexual partners in the past year (AOR 2.15, 95% CI 1.05–4.42); and having low self-perceived risk (AOR 1.97, 95% CI 1.05–3.68) were significantly associated with increased odds of unsafe sex (Table 3). Having tested for HIV in the past year (AOR 0.41, 95% CI 0.20–0.85) and knowing where to obtain condoms (AOR 0.26, 95% CI 0.11–0.62) were significantly associated with decreased odds of unsafe sex.

Table 3.

Factors associated with unsafe sex among never married, non-cohabiting youth aged 15–19 years, KAIS 2012 (N=423)

| Variable | Unweighted N (total†) | Unweighted unsafe sex n | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 249 | 93 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Female | 174 | 66 | 1.02 (0.63 – 1.66) | 0.934 | 1.19 (0.61 – 2.32) | 0.619 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 122 | 43 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Urban | 301 | 116 | 0.97 (0.62 – 1.52) | 0.889 | 0.67 (0.35 – 1.28) | 0.225 |

| Region | ||||||

| Nairobi* | 44 | 14 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Central | 23 | 11 | 3.10 (1.08 – 8.86) | 0.281 | 3.58 (1.01 – 12.75) | 0.049 |

| Coast* | 47 | 18 | 1.30 (0.59 – 2.84) | - | 0.68 (0.20 – 2.28) | 0.529 |

| Eastern | 54 | 17 | 1.00 (0.43 – 2.31) | - | 0.34 (0.07 – 1.55) | 0.163 |

| Nyanza | 103 | 36 | 1.30 (0.64 – 2.62) | - | 1.25 (0.39 – 3.98) | 0.705 |

| Rift Valley | 85 | 35 | 1.76 (0.84 – 3.68) | - | 1.18(0.37 – 3.78) | 0.777 |

| Western | 67 | 28 | 1.85 (0.78 – 4.40) | - | 1.65(0.49 – 5.58) | 0.422 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Primary or lower | 249 | 110 | 2.30 (1.52 – 3.49) | <.001 | 4.11 (2.12 – 7.96) | <.001 |

| Secondary or higher | 174 | 49 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 81 | 37 | ref | - | - | - |

| Second | 129 | 50 | 0.94 (0.45 – 1.97) | 0.535 | - | - |

| Third | 85 | 30 | 0.72 (0.34 – 1.53) | - | - | - |

| Fourth | 67 | 22 | 0.65 (0.31 – 1.38) | - | - | - |

| Richest | 61 | 20 | 0.62 (0.28 – 1.39) | - | - | - |

| Early sexual debut | ||||||

| No | 313 | 101 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 106 | 55 | 2.27 (1.36 – 3.78) | 0.002 | 1.95 (1.03 – 3.69) | 0.04 |

| Ever tested for HIV* | ||||||

| No | 148 | 73 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 275 | 86 | 0.43 (0.28 – 0.65) | <.001 | 0.71 (0.35 – 1.42) | 0.329 |

| Tested for HIV in the last year | ||||||

| No | 231 | 108 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 192 | 51 | 0.36 (0.24 – 0.54) | <.001 | 0.41 (0.20 – 0.85) | 0.016 |

| Knows where to get a condom | ||||||

| No | 54 | 31 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 369 | 128 | 0.40 (0.20 – 0.78) | 0.007 | 0.26 (0.11 – 0.62) | 0.002 |

| Ever received money, gifts or favours for sex* | ||||||

| No | 390 | 142 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes* | 33 | 17 | 1.63 (0.76 – 3.53) | 0.213 | 3.04 (1.11 – 8.33) | 0.03 |

| Had multiple (2+) sex partners in past year** | ||||||

| No | 358 | 129 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 62 | 30 | 1.75 (0.96 – 3.19) | 0.066 | 2.15 (1.05 – 4.42) | 0.037 |

| Illicit drug use in past year | ||||||

| No | 350 | 129 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 73 | 30 | 1.50 (0.78 – 2.90) | 0.226 | 1.99 (0.89 – 4.44) | 0.093 |

| Self–perception of HIV risk | ||||||

| No risk | 140 | 41 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Low risk | 144 | 49 | 1.29 (0.72 – 2.30) | 0.057 | 1.97 (1.05 – 3.68) | 0.034 |

| Moderate/high risk | 88 | 40 | 1.93 (1.13 – 3.32) | - | 1.90 (0.98 – 3.67) | 0.056 |

OR: Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval

Sample size less than 50 observations; therefore estimate may be unreliable.

Due to missing responses, totals vary between variables. Bolded estimates reflect statistically significant associations.

Sexual behaviours of young people aged 20–24 years

Among young people aged 20–24 years who had never been married or cohabited, males (80.5%, 95% CI 76.6–84.3) were more likely to have ever had sex than females (70.7%, 95% CI 65.5–75.8) (Table 2). Males (18.0%, 95% CI 13.9–22.1) were also more likely than females (8.5%, 95% CI4.9–12.1) to report early sexual debut. Among those who had ever had sex, 73.1% (95% CI 69.8–76.3) were sexually active in the past year. Of these, 22.2% (95% CI 17.4–27.1) of males and 6.4% (95% CI 2.7–10.0) of females had two or more sexual partners in the past year. Less than half knew the HIV status of sexual partners in the past year(43.4%, 95% CI 38.9–47.8); males were less likely to know the HIV status of sexual partners (35.4%, 95% CI 29.9–40.9) than females (61.1%, 95% CI 54.1–68.1). Among those who were sexually active in the past year, only 44.9% (95% CI39.2–50.5) of males and 36.8% (95% CI 30.1–43.4) of females used condoms consistently in the past year. More males(31.9%, 95% CI 26.4–37.5) than females (24.1%, 95% CI18.1–30.1) engaged in unsafe sex in the past year. Overall,9.9% (95% CI 5.3–14.6) of females and 3.0% of males (95% CI 1.3–4.8) had ever received money, gifts, or favours for sex in their lifetime.

Overall, more females (87.8%, 95% CI 83.8–91.8) than males (69.6%, 95% CI 64.7–74.4) had ever been tested for HIV. Similarly, among those who were sexually active in the past year, more females had tested for HIV in the past year (60.3%, 95% CI 53.2–67.5) compared to males (47.0%, 95% CI 41.7–52.4).

In multivariate analysis, having completed primary or lower level of education compared to higher level of education (AOR 1.87, 95% CI 1.12–3.14); having ever received money, gifts or favours in exchange for sex (AOR 2.55, 95% CI 1.03–6.32); and having multiple sexual partners in the past year (AOR 3.10, 95% CI 1.79–5.38) were associated with higher adjusted odds of unsafe sex (Table 4). Residence in Central, Eastern and Nyanza provinces compared to Nairobi (Central AOR 0.25, 95% CI 0.09–0.70; Eastern AOR 0.33, 95% CI 0.13–0.80; Nyanza AOR 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.67); being in the highest wealth quintile compared to the poorest (AOR 0.29, 95% CI 0.10–0.84); and having ever been tested for HIV (AOR 0.50, 95% CI 0.28–0.90) or having been tested for HIV in the past year (AOR 0.51, 95% CI 0.30–0.87) were associated with lower adjusted odds of engaging in unsafe sex.

Table 4.

Factors associated with unsafe sex among never married, non-cohabiting youth aged 20–24 years, KAIS 2012 (N=582)

| Variable | Unweighted N | Unweighted unsafe sex n | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 216 | 120 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Female | 366 | 50 | 0.68 (0.44 – 1.04) | 0.076 | 0.95 (0.54 – 1.67) | 0.851 |

| Residence | ||||||

| Rural | 311 | 86 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Urban | 271 | 84 | 1.21 (0.81 – 1.81) | 0.344 | 0.96 (0.50 – 1.87) | 0.915 |

| Region | ||||||

| Nairobi | 135 | 46 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Central* | 41 | 8 | 0.38 (0.16 – 0.90) | 0.013 | 0.25 (0.09 – 0.70) | 0.008 |

| Coast | 77 | 18 | 0.56 (0.27 – 1.17) | - | 0.39 (0.13 – 1.17) | 0.093 |

| Eastern | 87 | 24 | 0.69 (0.35 – 1.33) | - | 0.33 (0.13 – 0.80) | 0.014 |

| Nyanza | 69 | 11 | 0.34 (0.14 – 0.83) | - | 0.23 (0.08 – 0.67) | 0.007 |

| Rift Valley | 112 | 36 | 0.75 (0.41 – 1.36) | - | 0.52 (0.24 – 1.13) | 0.098 |

| Western | 61 | 27 | 1.31 (0.73 – 2.37) | - | 0.48 (0.18 – 1.28) | 0.142 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Primary or lower | 173 | 74 | 2.23 (1.45 – 3.44) | <.001 | 1.87 (1.12 – 3.14) | 0.017 |

| Secondary or higher | 409 | 96 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Wealth index | ||||||

| Poorest | 70 | 30 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Second | 78 | 22 | 0.52 (0.23 – 1.17) | 0.036 | 0.46 (0.17 – 1.22) | 0.117 |

| Third | 99 | 30 | 0.58 (0.28 – 1.20) | - | 0.51 (0.20 – 1.31) | 0.161 |

| Fourth | 150 | 44 | 0.57 (0.31 – 1.06) | - | 0.53 (0.21 – 1.36) | 0.187 |

| Richest | 185 | 44 | 0.34 (0.17 – 0.66) | - | 0.29 (0.10 – 0.84) | 0.023 |

| Early sexual debut | ||||||

| No | 495 | 141 | ref | - | - | - |

| Yes | 74 | 26 | 1.22 (0.66 – 2.26) | 0.518 | - | - |

| Ever tested for HIV* | ||||||

| No | 128 | 68 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 452 | 102 | 0.28 (0.18 – 0.43) | <.001 | 0.50 (0.28 – 0.90) | 0.021 |

| Tested for HIV in the last year | ||||||

| No | 278 | 112 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 304 | 58 | 0.34 (0.22 – 0.51) | <.001 | 0.51 (0.30 – 0.87) | 0.014 |

| Knows where to get a condom | ||||||

| No | 28 | 15 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 554 | 155 | 0.40 (0.17 – 0.94) | 0.035 | 0.41 (0.13 – 1.31) | 0.132 |

| Ever received money, gifts or favours for sex* | ||||||

| No | 549 | 157 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 33 | 13 | 1.56 (0.76 – 3.22) | 0.228 | 2.55 (1.03 – 6.32) | 0.043 |

| Had multiple (2+) sex partners in past year** | ||||||

| No | 474 | 123 | ref | - | ref | - |

| Yes | 98 | 47 | 2.43 (1.49 – 3.95) | <.001 | 3.10 (1.79 – 5.38) | <.001 |

| HIllicit drug use in past year | ||||||

| No | 428 | 126 | ref | - | - | - |

| Yes | 154 | 44 | 0.86 (0.54 – 1.38) | 0.537 | - | - |

| Self-perception of HIV risk | ||||||

| No risk | 154 | 40 | ref | - | - | - |

| Low risk | 273 | 75 | 1.11 (0.64 – 1.93) | 0.398 | - | - |

| Moderate/high risk | 117 | 41 | 1.52 (0.78 – 2.97) | - | - | - |

OR: Odds Ratio; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval

Sample size less than 50 observations; therefore estimate may be unreliable.

Due to missing responses, totals vary between variables. Bolded estimates reflect statistically significant associations.

Sexual behaviours in 2007 and 2012

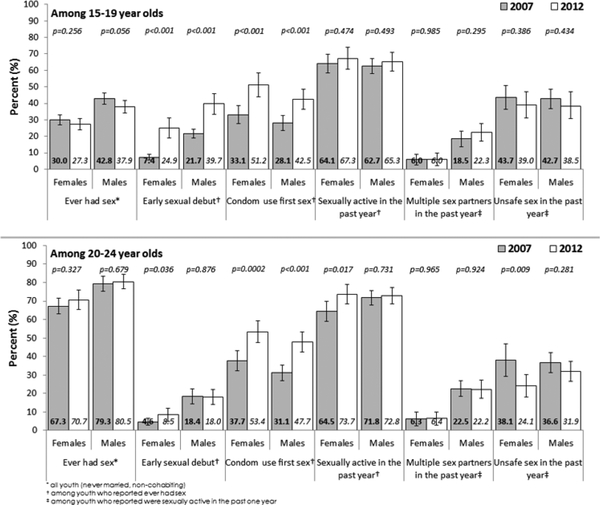

Among males aged 15–19 years, there were significant increases in early sexual debut from 21.7% (95% CI 19.1–24.3) in 2007 to 39.7% (95% CI 33.5–45.8) in 2012 and condom use at first sex from 28.1% (95% CI 23.4–32.7) in 2007 to 42.5% (95% CI 36.4–48.5) in 2012 (Figure 1). Among females aged 15–19, there were significant increases in early sexual debut from 7.4% (95% CI 5.7–9.0) in 2007 to 24.9% (95% CI 19.0–30.9) in 2012. There were no significant differences among males and females aged 15–19 in unsafe sex between 2007 and 2012.

Figure 1.

Sexual behaviour of Kenyan youth by age, sex and year.

Among males aged 20–24 years, there was a significant increase in condom use at first sex from 31.1% (95% CI26.9–35.2) in 2007 to 47.7% (95% CI 42.3–53.1) in 2012 coupled with a decline in unsafe sex from 36.6% (95% CI 31.3–42.0) in 2007 to 24.1% (95% CI 18.1–30.1) in 2012. Among women aged 20–24 years, there was a significant increase in condom use at first sex from 37.7% (95% CI32.2–43.2) in 2007 to 53.4% (95% CI 47.4–56.9) in 2012 and a significant decline in unsafe sex (from 38.1%, 95% CI29.3–46.8 in 2007 to 24.1%, 95% CI 18.1–30.1, p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This population-based analysis confirms that young persons in Kenya are engaging in high-risk behaviours that contribute to ongoing HIV transmission in this population. High-risk behaviours include early sexual debut, multiple sexual partnerships, transactional sex, unsafe sex with partners of unknown or sero-discordant HIV status, low HIV testing rates and lack of awareness about sexual partner HIV status. Adolescent girls aged 15–19 years were especially vulnerable, with a notably higher risk of engaging in unsafe sex compared to young men in the same age group and young women aged 20–24 years. In spite of this, young women who were engaging in unsafe sex perceived themselves to be at low risk for HIV. We found that secondary education was associated with safer sexual behaviours, a finding that underscores the importance of supporting young people to remain in school as part of HIV prevention efforts (Kirby, 2002). School attendance has been shown to play an important role in protecting youth from engaging in HIV-related risk behaviours such as early sexual debut and multiple sexual partners (Jukes, Simmons & Bundy, 2008; Hargreaves, Morison & Kim, 2008). Moreover, behavioural interventions delivered to youth in school allow for direct exposure to HIV prevention messages, providing school-based youth with the knowledge and tools to avoid or delay sexual risk behaviour (Coates, Richter & Caceres, 2008; Kirby, 2002).

Although transactional sex was not common, having engaged in transactional sex and being poor were significantly associated with unsafe sex among young persons aged 20–24 years. These findings highlight the economic and social factors that affect behaviour, including decisions on who to have sex with and the ability to negotiate protective behaviour within these partnerships. Innovative approaches to address the structural drivers that are linked with HIV risk among young persons in economically disadvantaged settings should be considered together with behavioural interventions. For example, cash transfers (regular monetary payments to individuals who are eligible) that have been associated with a reduction in high-risk sexual behaviours and improved educational outcomes among young people offer promising options, especially for adolescent girls and young women (Pettifor, McCoy & Padian, 2012; Baird, Garfein & McIntosh, 2012;Handa, Halperin, Pettifor et al, 2014).

Interestingly our results support regional differences in unsafe sex among youth in Kenya. Central province, a region bordering the capital city of Nairobi and with a relatively low burden of HIV infection (NASCOP, 2009), was associated with lower odds of unsafe sex among youth aged 20–24. Nyanza province, the region with the highest HIV prevalence in the country (NASCOP, 2009), and Eastern province also observed a similar protective association with unsafe sex among older youth. Encouragingly, our findings could suggest that HIV prevention interventions in Central, Eastern and Nyanza regions may be achieving some success in reducing unsafe sex among young people aged 20–24. However, starting earlier with age-appropriate messages about safer sex may be needed for children entering adolescence to ensure that they are receiving the right messages to inform their future sexual decision-making.

Between 2007 and 2012, we observed increases in early sexual debut among the younger age group coupled with increases in condom use at first sex in the two age groups and a decline in unsafe sex among women in the older age group. The increase in condom use at first sex among young men and women in the two age groups is consistent with global trends reported for young people in other sub-Saharan African countries (World Health Organization-WPRO, 2015). We found that knowing where to obtain a condom was associated with lower odds of engaging in unsafe sex in the two age groups. Ensuring that condoms are accessible and used consistently remains a key priority of HIV prevention efforts. The low knowledge of sexual partner HIV status in our findings underscores the importance of integrating HIV testing and counselling in interventions targeting sexually active young people. The low HIV testing among young men in 2012 emphasizes the continued need to scale-up HIV testing services that promote self and partner HIV testing among young men.

Our analysis has some limitations. Our definition of unsafe sex relied on self-reported information on partner HIV status which may not have been reported accurately. However, our definition of unsafe sex was more rigorous than previous analyses that defined unsafe sex as sex with a non-marital or non-cohabiting partner (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics & ICF Macro, 2010). Additionally, since risk factors and outcomes were measured simultaneously, we were unable to discern directionality of associations. Temporal trends in sexual behaviours were descriptive and did not adjust for demographic changes in the sample that may have been associated with our outcomes of interest. We note, however, that the KAIS 2007 and KAIS 2012 samples did not differ by age, sex, or regional distribution. Lastly, we excluded married and cohabiting youth aged 15–24 years from this analysis, a sub-group that comprised 28% of youth aged 15–24 years and where substantial transmission is expected to occur.

CONCLUSION

In spite of these limitations, our comprehensive analysis of sexual behaviours of young people provides important information to inform HIV prevention priorities for young people in Kenya and supports the new global focus to prioritize young people as a key population that can reverse the HIV epidemic. Our findings underscore the importance of staying in school, the need to scale-up gender- and age-appropriate HIV prevention interventions that integrate structural interventions with educational messages around safer sex, fewer sexual partnerships, condom access and use and universal awareness of not only one’s own status but also the HIV status of partners. Our findings also show progress in the national HIV response in reducing HIV risk behaviours among young people and particularly among young men. Continued surveillance of behavioural trends among young people in nationally representative surveys is needed to monitor impact as new HIV prevention strategies among youth are rapidly scaled–up over the next five years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Kevin De Cock, George Rutherford, Joy Mirjahangir, Mike Grasso, and Nadine Sunderland for reviewing the manuscript. We acknowledge the KAIS Study Group for their contributions to the design of the survey and collection of the data set. Willis Akhwale, Sehin Birhanu, John Bore, Angela Broad, Robert Buluma, Thomas Gachuki, Jennifer Galbraith, Anthony Gichangi, Beth Gikonyo, Margaret Gitau, Joshua Gitonga, Mike Grasso, Malayah Harper, Andrew Imbwaga, Muthoni Junghae, Mutua Kakinyi, Samuel Mwangi Kamiru, Nicholas Owenje Kandege, Lucy Kanyara, Yasuyo Kawamura, Timothy Kellogg, George Kichamu, Andrea Kim, Lucy Kimondo, Davies Kimanga, Elija Kinyanjui, Stephen Kipkerich, Dan Koros, Danson Kimutai Koske, Boniface O. K’Oyugi, Veronica Lee, Serenita Lewis, William Maina, Ernest Makokha, Agneta Mbithi, Joy Mirjahangir, Ibrahim Mohamed, Rex Mpazanje, Nicolas Muraguri, Patrick Mureithi, Lilly Muthoni, James Mutunga, Jane Mwangi, Mary Mwangi, Sophie Mwanyumba, Silas Mulwa, Francis Ndichu, Anne Ng’ang’a, James Ng’ang’a, John Gitahi Ng’ang’a, Lucy Ng’ang’a, Carol Ngare, Bernadette Ng’eno, Inviolata Njeri, David Njogu, Bernard Obasi, Macdonald Obudho, Edwin Ochieng, Linus Odawo, James Odek, Jacob Odhiambo, Caleb Ogada, Samuel Ogola, David Ojakaa, James Kwach Ojwang, George Okumu, Patricia Oluoch, Tom Oluoch, Kenneth Ochieng Omondi, Osborn Otieno, Yakubu Owolabi, Bharat Parekh, George Rutherford, Sandra Schwarcz, Shahnaaz Sharrif, Victor Ssempiijja, Lydia Tabuke, Yuko Takenaka, Mamo Umuro, Brian Eugene Wakhutu, Cecilia Wandera, John Wanyungu, Wanjiru Waruiru, Anthony Waruru, Paul Waweru, Larry Westerman, and Kelly Winter.

This publication was made possible by support from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through cooperative agreements [#PS001805, GH000069, and PS001814] through the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Global HIV/AIDS (DGHA).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention and the Government of Kenya.

REFERENCES

- Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, & Ozler B (2011). Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomized trial. Lancet, 379(9823), 1320–1329. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin HB, Sipe TA, Elder R, Mercer SL, Chattopadhyay SK, Jacob V,… & Community Preventive ServicesTask Force. (2009). Community Preventive Services Task Force. The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: two systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med, 42(3), 272–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Richter L, & Caceres C (2008). Behavioral strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet, 372(9639), 669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Marshall KJ, Aupont LW, Jacobs ED, Mizuno Y, Kay LS …& O’Leary A (2009).The Efficacy of HIV/STI BehaviouralInterventions for African American Females in the United States: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Public Health, 99(11), 2069–2078. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbes L, Crepaz N, Lyles C, Kennedy G, & Rutherford G (2008). The efficacy of behavioural interventions in reducing HIV risk s and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African Americans. AIDS, 22(10), 1177–1194. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282ff624er [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AM, Mavedzenge SN, Plummer ML, & Ross DA (2012). The sexual behaviour of adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: patterns and trends from national surveys. Trop Med Int Health, 17(7), 796–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant M, & Maticka–Tyndale E (2004). School-based HIV prevention programmes for African Youth. Soc Sci. Med, 58(7), 1337–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00331-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa S, Halpern CT, Pettifor A, & Thirumurthy H (2014). The Government of Kenya’s Cash Transfer Program Reduces the Risk of Sexual Debut among Young People Age 15–25. PLoS One, 9(1), e85473.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves JR, Morison LA, & Kim JC (2008). The association between school attendance, HIV infection, and sexual behaviour among young people in rural South Africa. J Epidemiol Community Health, 62(2), 113–119. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS.(2015). All In, 2015. Retrieved from http://allintoendadolescentaids.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/ALL-IN-Launch-Document.pdf

- Jukes M, Simmons S, & Bundy D (2008). Education and vulnerability: the role of schools in protecting young women and girls from HIV in southern Africa. AIDS, 22(Suppl 4), S41–S56. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000341776.71253.04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Ministry of Health. (n.d.). Kenya AIDS Strategic Framework 2014/2015–2018/2019. National AIDS Control Council. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) & ICF Macro. (2010). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. Calverton, Maryland: KNBS & ICF Macro. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D (2002). The impact of schools and school programs upon adolescent sexual behaviour. J Sex Res, 39(1), 27–33. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D, Obasi A, & Laris BA (2006). The effectiveness of sex education and HIV education interventions in schools in developing countries. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, 938, 103–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michielsen K (2012). HIV prevention for young people in Sub-Saharan Africa: effectiveness of interventions and areas for improvement. Evidence from Rwanda. Afr. Focus, 25(2), 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Michielsen K, Chersich MF, Luchters S, Ronan Van Rossem P, & Temmerman M (2010). Effectiveness of HIV prevention for youth in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials. AIDS, 24(8), 1193–1202. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283384791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS/STI Control Programme. (2009). Kenya2007 Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey: Final Report. Nairobi: NASCOP. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS and STI Control Programme. (2010).National Guidelines for HIV Testing and Counselling in Kenya, 2nd Edition Nairobi, Kenya: NASCOP. [Google Scholar]

- National AIDS/STI Control Programme. (2013). Kenya 2012 Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey: Final Report. Nairobi: NASCOP. [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor AE, Levandowski BA, MacPhail C, Padian NS, Cohen M, & Rees H (2008). Keep them in school: the importance of education as a protective factor against HIV infection among young South African women. Int J Epidemiol, 37(6), 1266–1273. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, McCoy SI, & Padian N (2012). Paying to prevent HIV infection in young women? Lancet, 379(9823), 1280–1282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60036-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, O’Brien K, Macphail C, Miller WC & Rees H (2009). Early coital debut and associated HIV risk factors among young women and men in South Africa. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health, 35(2), 82–90. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.35.082.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rositch AF, Cherutich P, Brentlinger P, Kiarie JN,Nduati R, & Farquhar C (2012). HIV infection and sexual partnerships and behaviour among adolescent girls in Nairobi, Kenya. Int J STD AIDS, 23(7), 468–474. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2012.011361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein SO, & Johnson K (2004). The DHS WealthIndex DHS Comparative Reports No. 6. Calverton, Maryland: ORC Macro. [Google Scholar]

- Stockl H, Karla N, Jacobi J, & Watts C (2013). Is early sexual debut a risk factor for HIV infection among women in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review. Am J Reprod Immunol, 69(Suppl 1), 27–40. doi: 10.1111/aji.12043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and United Nations Programme on Youth. (n.d.). Regional Overview: Youth in Africa, undated. Retrieved from http://social.un.org/youthyear/docs/Regonal$20Overview%20Youth%20in%20Africa.pdf

- United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). (n.d.) Working together for an AIDS-free future for girls and women. Retrieved from http://www.pepfar.gov/partnerships/ppp/dreams/index.htm

- Waruiru W, Kim AA, Kimanga D, Ng’ang’a J, Schwarcz S, Kimondo L, Ng’ang’a A, Umuro M, Mwangi M, Ojwang’ JK, Maina WK, & KAIS Study Group. (2014). The Kenya Aids Indicator Survey 2012: Rationale, methods, description of participants, and response rates. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 66(Suppl 1), S3–S12. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization-WPRO. (2015). Fact sheet on adolescent health. Retrieved from http://www.wpro.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/docs/fs_201202_adolescent_health/en/