Abstract

Enveloped viruses gain entry into host cells by fusing with cellular membranes, a step that is required for virus replication. Coronaviruses, including the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), fuse at the plasma membrane or use receptor-mediated endocytosis and fuse with endosomes, depending on the cell or tissue type. The virus spike (S) protein mediates fusion with the host cell membrane. We have shown previously that an Abelson (Abl) kinase inhibitor, imatinib, significantly reduces SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV viral titres and prevents endosomal entry by HIV SARS S and MERS S pseudotyped virions. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are classified as BSL-3 viruses, which makes experimentation into the cellular mechanisms involved in infection more challenging. Here, we use IBV, a BSL-2 virus, as a model for studying the role of Abl kinase activity during coronavirus infection. We found that imatinib and two specific Abl kinase inhibitors, GNF2 and GNF5, reduce IBV titres by blocking the first round of virus infection. Additionally, all three drugs prevented IBV S-induced syncytia formation prior to the hemifusion step. Our results indicate that membrane fusion (both virus–cell and cell–cell) is blocked in the presence of Abl kinase inhibitors. Studying the effects of Abl kinase inhibitors on IBV will be useful in identifying the host cell pathways required for coronavirus infection. This will provide an insight into possible therapeutic targets to treat infections by current as well as newly emerging coronaviruses.

Keywords: coronavirus, SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, IBV, cell-cell fusion, virus-cell fusion, Abl kinase, Abl1, Abl2, imatinib, GNF2, GNF5

Introduction

Coronaviruses are enveloped RNA viruses and include those that cause the common cold as well as the highly pathogenic severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). In order to gain entry into host cells, all enveloped viruses, including coronaviruses, fuse with cellular membranes. Coronaviruses bind to cell surface receptors and fuse with the plasma membrane or are endocytosed and fuse with endosomes. This fusion step is required in order for the viral genome to be delivered to the host cell cytoplasm for replication. SARS and MERS coronaviruses fuse with late and early endosomes, respectively, and also at the plasma membrane [1–4]. The virus S protein mediates fusion between viral and host cell membranes.

Since the outbreaks caused by SARS-CoV in 2003 and MERS-CoV in 2012, these viruses have been studied extensively in order to understand infection and pathogenicity, with the goal of identifying therapeutic targets. A high-throughput screen identified an Abl kinase inhibitor, imatinib, as an inhibitor of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [5]. Abl kinases are non-receptor tyrosine kinases. Abl1 and Abl2 are localized to the cytoplasm, and Abl1 is also found in the nucleus and mitochondria [6–8]. Two Abl kinases, Abl1 and Abl2, are expressed in human cells, and are involved in several cellular processes, ranging from embryonic morphogenesis to the mediation of viral infections [9, 10]. Imatinib is a small-molecule inhibitor specifically designed to target the Abl kinase portion of the BCR-Abl protein [11], which results from a chromosomal translocation and causes chronic myeloid leukaemia [12–14]. Previously, we have shown that imatinib blocks the entry of pseudotyped virions containing SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV S protein [15]. Inhibition of SARS and MERS coronavirus entry by imatinib implicates Abl kinase activity in coronavirus infection, and reports from other groups demonstrate Abl kinase involvement in infections by several other viruses [16–23]. This strongly suggests that the Abl kinase signalling pathway is a promising topic to investigate for the development of antiviral therapies.

Based on results from our previous report [15], we hypothesize that Abl kinase activity is required for the entry of other coronaviruses, presumably for virus–cell fusion. The classification of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV as BSL-3 pathogens and SARS-CoV as a select agent limits the experimental methods that can be performed with the live viruses. Additionally, the membrane composition of pseudotyped virions differs from that of true virions, since pseudotyped virions bud from the plasma membrane, while true virions bud from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)–Golgi intermediate compartment [24, 25]. This could lead to differences in virus–cell fusion and entry mechanisms. It is important to evaluate the anti-CoV effects in a live virus system and it is advantageous to find a BSL-2 coronavirus that can be used as a model of infection. Here, we report the effects of imatinib and two other Abl kinase inhibitors, GNF2 and GNF5, on IBV infection. We show that the Abl kinase inhibitors interfere with the first round of IBV infection, indicating an inhibition of virus–cell fusion. In addition, we directly demonstrate that cell–cell fusion and syncytia formation mediated by IBV S is inhibited by imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 prior to hemifusion, suggesting a role for Abl kinases in both virus–cell and cell–cell fusion events. IBV will be an excellent model to determine the mechanism of Abl kinase action during coronavirus entry in order to find new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Results

IBV titres are reduced in infected Vero cells after treatment with Abl kinase inhibitors

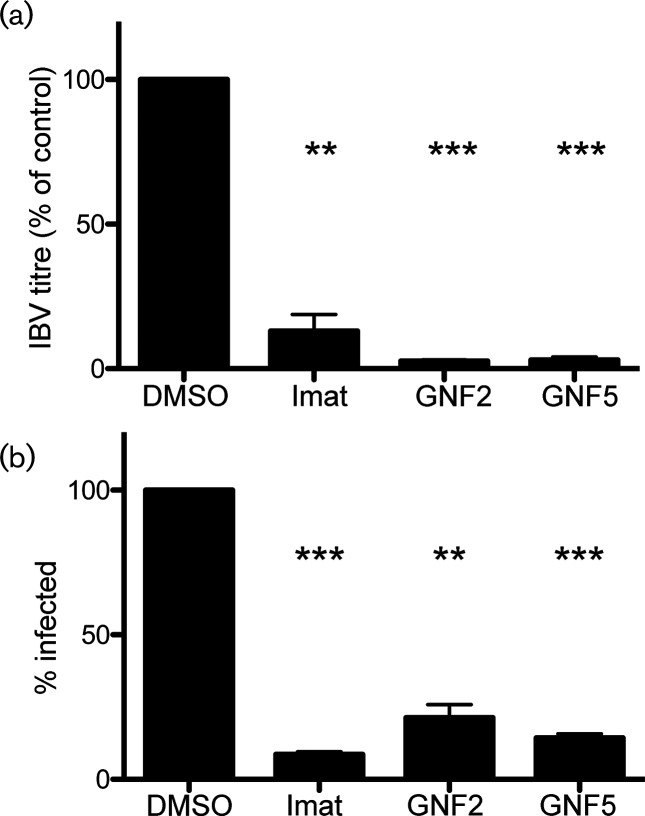

We have shown previously that imatinib lowers SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV titres [15]. We tested the effects of imatinib, as well as two other Abl kinase inhibitors, GNF2 and GNF5, on IBV infection in order to determine whether IBV could be used as a model to investigate Abl kinase involvement in coronavirus infection. We used two different types of inhibitors in order to determine target specificity as well the mechanism of inhibition. Imatinib is a competitive inhibitor that binds near the ATP-binding pocket, preventing the binding of ATP [26, 27]. Imatinib only binds when the Abl kinase is in the closed, inactive conformation [27]. GNF2 and GNF5 bind to the auto-inhibitory myristate-binding site of the Abl kinase, leading to inactivation of the active kinase by promoting the closed conformation [28]. Imatinib has several cellular targets, while GNF2 and GNF5 specifically inhibit the Abl kinases [28, 29]. Treating infected cells with these specific inhibitors allowed us to evaluate the likelihood of Abl kinase involvement in coronavirus infection as opposed to any of the other cellular targets of imatinib. Vero cells were infected with IBV at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 0.1 in the absence and presence of the three inhibitors. Supernatants were harvested 18 h post-infection, and a plaque assay was used to measure the viral titres of all samples. The results from this experiment showed that all three drugs significantly decreased the virus titre. Imatinib lowered the viral titre by ~90 % when compared to control, and GNF2 and GNF5 lowered the titre by ~95 % (Fig. 1a and Table S1a, b, available in the online version of this article).

Fig. 1.

IBV infection is suppressed by Abl kinase inhibitors. Vero cells were pre-treated for 1 h with dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) or 10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 at 37 °C. Cells were adsorbed at 37 °C for 1 h with IBV at an m.o.i. of 0.1 in the presence of DMSO or drug. Cells were washed and fresh medium containing DMSO or drug was added and infection was allowed to proceed for 18 h at 37 °C. (a) Supernatants were harvested and used for plaque assays to determine the viral titre. (b) Immunofluorescence staining of the IBV S protein was used to count the number of infected cells in the presence of DMSO or drug. In excess of 1000 cells were analysed per experimental condition in 3 independent experiments, and the % of cells infected was calculated by comparing the number of infected cells to the total number of cells analysed. The error bars represent the standard error and P values were calculated using a paired t-test. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Next, we determined whether the decrease in titre was due to reduced virus production in infected cells or the result of fewer cells being infected. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy using an antibody to the IBV S protein was used to count the number of infected cells in the absence and presence of the Abl kinase inhibitors. Our observations showed that imatinib and GNF5 reduced the number of cells infected by ~90 %, while GNF2 decreased the number of infected cells by ~80 % when compared to control (Fig. 1b). These results suggest that the decrease in IBV titre was due to a decrease in the number of cells infected. The inhibition by GNF2 and GNF5 suggests that Abl1 and/or Abl2 specifically play a role in IBV infection.

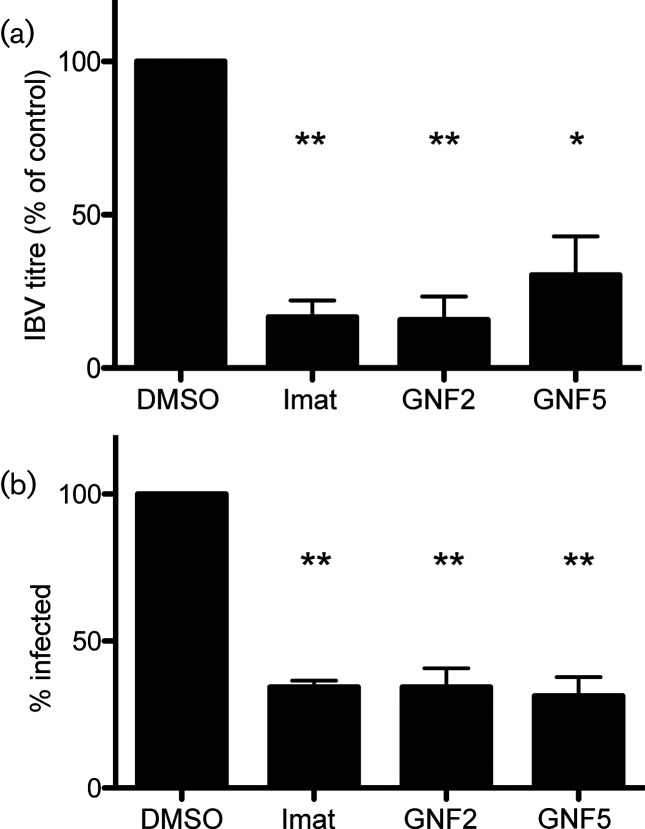

Abl kinase inhibitors prevent the first round of IBV infection

Previously, we showed that imatinib prevents the entry of pseudotyped viruses expressing SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV S protein [15]. In order to determine whether IBV is blocked at the entry step by Abl kinase inhibitors, we infected Vero cells at a high m.o.i and for a duration that would only allow one round of infection. Supernatants were harvested at 8 h post-infection, and IBV titres were measured using a plaque assay. The results from this experiment showed a significant decrease in virus titre when IBV-infected cells were treated with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 as compared to control. Imatinib and GNF2 reduced the titre by ~80 %, and GNF5 reduced it by 70 % (Fig. 2a and Table S1c, d). We also observed a 70 % decrease in the total number of cells infected after treatment with all three drugs (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Abl kinase inhibitors block the first round of IBV infection. Vero cells were pre-treated for 1 h with DMSO, 10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5. Cells were adsorbed with IBV at an m.o.i of 2 in the presence of DMSO or drug. Adsorption was performed at 4 °C to allow the synchronization of virus-receptor binding. The cells were washed, fresh medium containing DMSO or drug was added and infection was allowed to proceed for 8 h at 37 °C. (a) Supernatants were harvested and used for plaque assays to determine the viral titre. (b) Indirect immunofluorescence staining of the IBV S protein was used to count the number of infected cells in the presence of DMSO or drug. In excess of 500 cells were analysed per experimental condition in 3 independent experiments, and the % of cells infected was calculated by comparing the number of infected cells to the total number of cells analysed. The error bars represent the standard error and P values were calculated using a paired t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

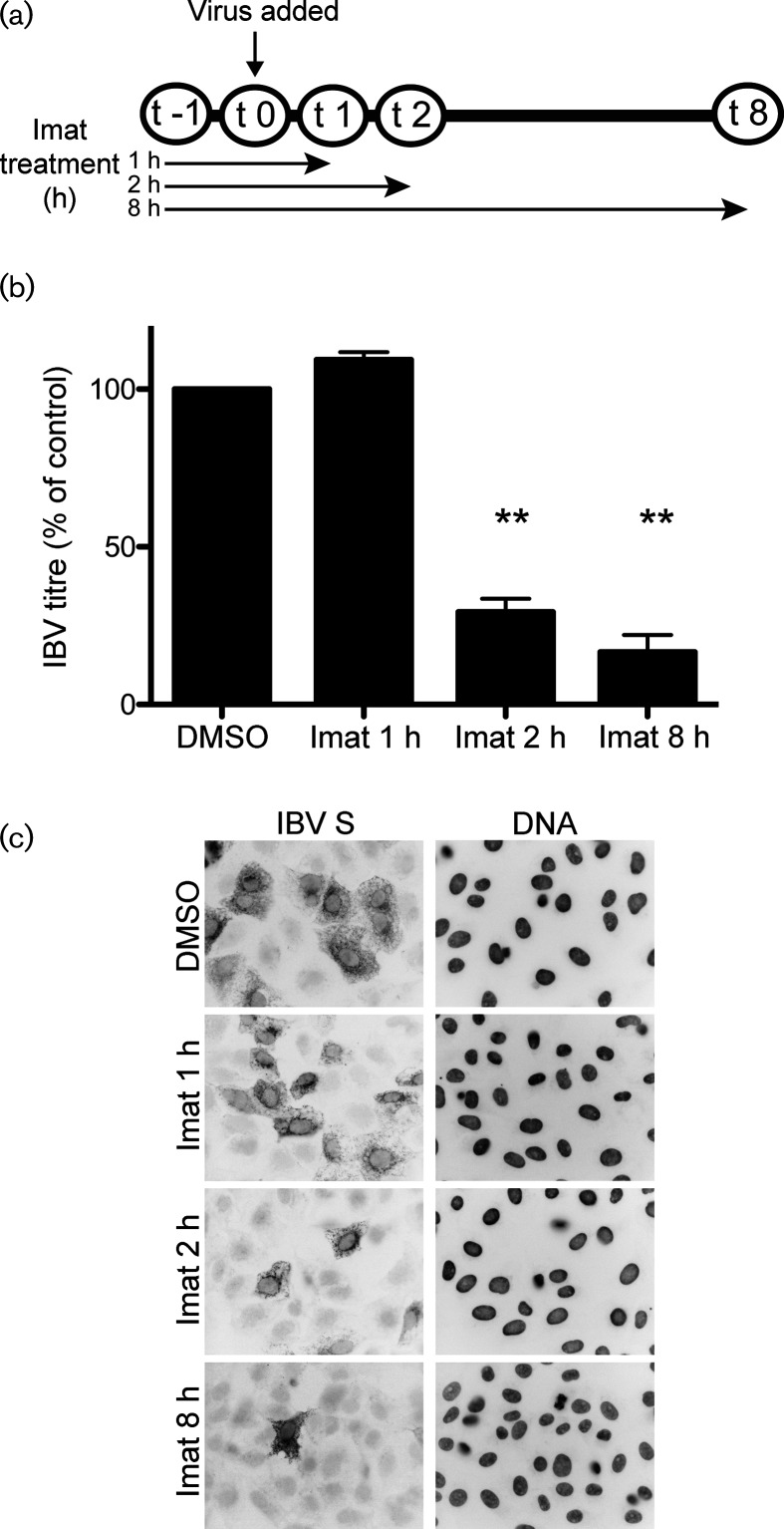

We considered that the decrease in number of cells infected could be due to decreased virus binding to host cell receptors. To address this, we infected Vero cells at a high m.o.i for 8 h and removed imatinib at indicated time points post-infection (Fig. 3a). All cells were pre-treated with DMSO or imatinib, and either DMSO or imatinib was present in the infection medium during adsorption. Pre-treatment occurred from t−1 through t0, and adsorption occurred from t0 through t1. Imatinib is a reversible inhibitor of Abl kinases [30] and we observed a rapid reversal of its effects on IBV infection after its removal from the cell culture medium. The results from this experiment showed that when imatinib was removed from the cell culture medium immediately after adsorption, infection proceeded normally and the viral titres matched those in untreated cells (Fig. 3b, imat 1 h; Fig. 3c, imat 1 h, Table S1e). However, when imatinib was present for at least 1 h post-adsorption during virus fusion and entry, the viral titres decreased significantly (Fig. 3b, imat 2 h; Fig. 3c, imat 2 h, Table S1e). Similar to the results in Fig. 2, imatinib treatment for the duration of infection decreased the IBV titres by ~80 % (Fig. 3b, imat 8 h; Fig. 3c, imat 8 h; Table S1e). We also observed a decrease in the number of cells infected when imatinib was present in the cell culture medium for at least 1 h prior to, and 1 h after, adsorption (Fig. 3b, imat 2 h; Fig. 3c, imat 2 h). This result suggests that imatinib does not affect virus binding to host cell receptors, but does interfere with virus entry. The results from these experiments demonstrate that Abl kinase inhibitors prevent the first round of infection by IBV, potentially through interference with virus–cell fusion.

Fig. 3.

Imatinib interferes with the entry step of IBV infection. Vero cells were pre-treated for 1 h at 37 °C with DMSO or 10 uM imatinib. Cells were adsorbed with IBV for 1 h at m.o.i. 2 in the presence of DMSO or imatinib. Adsorption was performed at 4 °C to allow synchronization of virus receptor-binding. The cells were washed, fresh medium containing DMSO or imatinib was added and infection was allowed to proceed for 8 h at 37 °C. (a) Schematic showing duration of imatinib treatment. (b) Supernatants were harvested and used for plaque assays to determine the viral titre. The results shown were calculated from three independent experiments. The error bars represent the standard error and P values were calculated using a paired t-test. **P<0.01. (c) Indirect immunofluorescence staining of the IBV S protein was used to visualize infected cells in the presence of DMSO or imatinib.

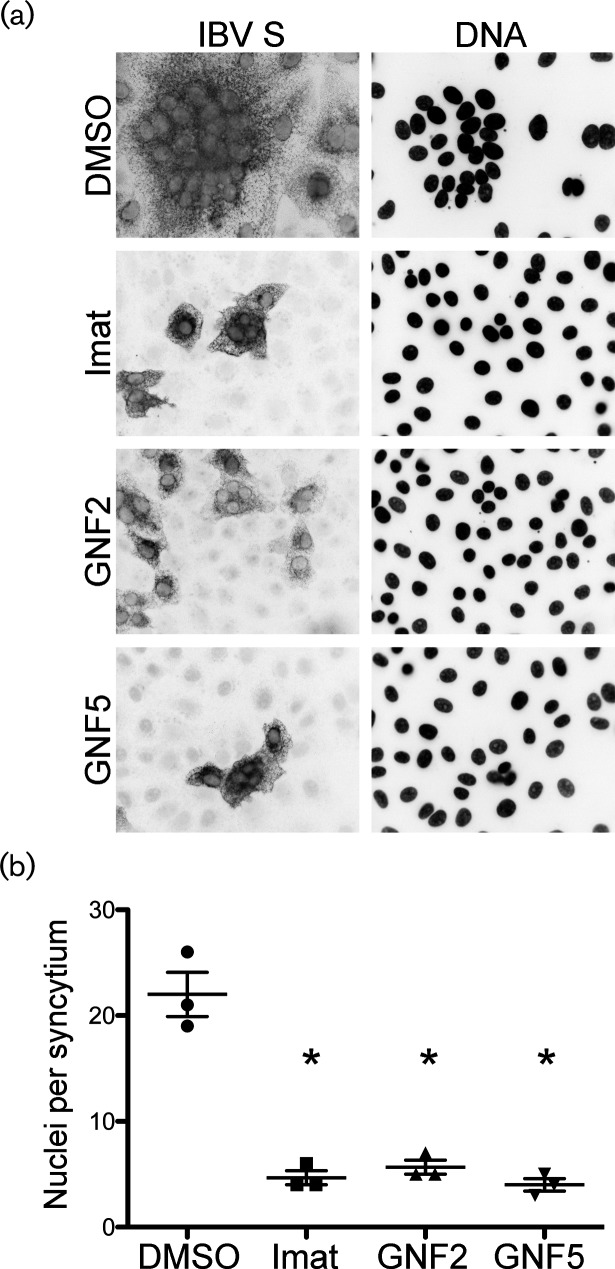

Abl kinase inhibitors prevent virus-induced syncytia formation

The infection of Vero cells by IBV leads to cell–cell fusion and the formation of multinucleated syncytia. Newly synthesized IBV S protein is incorporated into new virions that bud into the ER–Golgi intermediate compartment [25, 31], but the S protein is also transported to the cell surface and accumulates at the plasma membrane late in infection, as well as when introduced via expression vectors [32]. Just as S protein on the surface of the virion mediates virus–cell fusion, the S on the surface of infected cells mediates cell–cell fusion, resulting in syncytia formation. Because the viral S protein mediates both of these events, it seems likely that virus–cell and cell–cell fusion may use the same cellular mechanism. Due to the difficulty of capturing individual virus–cell fusion events, we analysed cell–cell fusion by measuring syncytium size in the absence and presence of imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5. In Vero cells that were infected with IBV, we observed syncytia formation with an average of 22 nuclei per syncytium (Fig. 4a, b). Treatment with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 resulted in a statistically significant reduction of nuclei per syncytium. Average syncytium size was reduced to 5, 6 and 4 nuclei for imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5, respectively, an ~95 % reduction in the presence of each drug (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4.

Abl kinase inhibitors prevent virus-induced syncytia formation in IBV-infected cells. Vero cells were pre-treated for 1 h at 37 °C with DMSO, 10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5. Cells were adsorbed for 1 h with IBV at an m.o.i of 0.1 in the presence of DMSO or drug. The cells were washed, fresh medium containing DMSO or drug was added and infection was allowed to proceed for 18 h at 37 °C. (a) Indirect immunofluorescence assay detecting the S protein in infected cells. (b) Quantification of nuclei per syncytium in the presence or absence of Abl kinase inhibitors. In excess of 50 syncytia were analysed in 3 independent experiments. The error bars represent the standard deviation and P values were calculated using a paired t-test. *P<0.05.

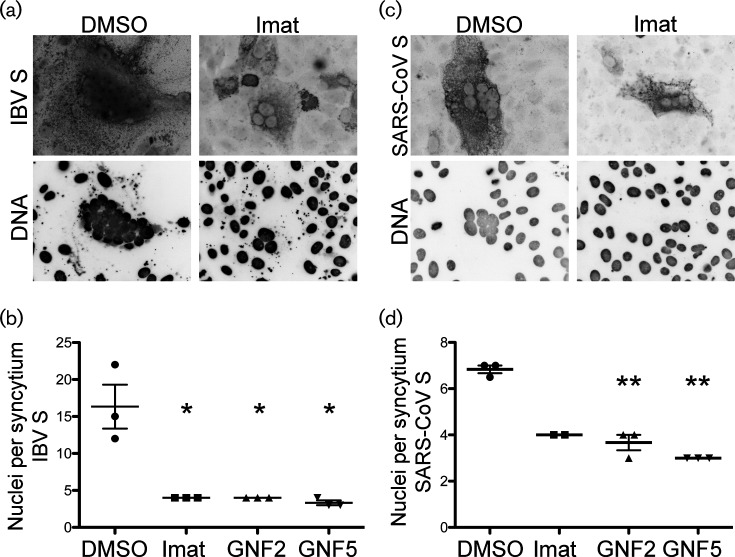

Next, we determined whether imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 inhibited syncytia formation induced by the S protein alone when expressed exogenously. Similar to infection, we observed the formation of syncytia containing an average of 16 nuclei when Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding IBV S (Fig. 5a, b). Treating IBV S-transfected cells with Abl kinase inhibitors significantly reduced the number of nuclei per syncytium to ~4 nuclei for imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5, an ~80 % reduction (Fig. 5a, b). Because SARS-CoV is also inhibited by imatinib [15], we wanted to determine whether Abl kinase inhibitors interfere with fusion induced by SARS-CoV S. To this end, we also tested the effects of all three drugs on syncytia formation produced by the SARS-CoV S protein. Vero cells were transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding SARS-CoV S. The number of nuclei per syncytium was reduced by 40 % by imatinib, by 50 % by GNF2 and by 60 % by GNF5, as compared to the number of nuclei per syncytium in untreated cells (Fig. 5c, d). The average syncytium size induced by SARS-CoV S was much smaller than that induced by IBV S (7 nuclei and 16 nuclei per syncytium, respectively), but treatment with all 3 drugs did reduce the average to 3 nuclei per syncytium for both IBV S and SARS-CoV S. Note that treatment with Abl kinase inhibitors not only reduced the number of nuclei per syncytium, but also the total number of syncytia. We did not quantify this observation, but while more than 50 syncytia containing greater than or equal to 3 nuclei were found in the control cells, we routinely found fewer than 10 syncytia in drug-treated samples. Additionally, there are only two data points for the SARS-CoV S, imatinib-treated cells due to the fact that no syncytia were found in one of the replicate experiments. Treatment with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 had no effect on the total number of cells expressing VSV-G after the transfection of a control plasmid (pCAGGS/VSV-G), demonstrating that the effects of these inhibitors were not due to differences in transfection efficiency (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrate that imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 interfere with syncytia formation mediated by the S protein both during IBV infection and when S protein is expressed exogenously in the absence of infection. The fact that we see the same phenotype with SARS-CoV S and IBV S reinforces the idea that IBV can be used as a model coronavirus to study Abl kinase involvement in coronavirus infection.

Fig. 5.

Abl kinase inhibitors prevent syncytia formation in cells expressing coronavirus S proteins exogenously. Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding IBV S (a, b) or SARS-CoV S (c, d) and DMSO or 10 µM imatinib and GNF2 or GNF5 were added to the medium 3 h post-transfection. The cells were examined 48 h post-transfection. The top images show an indirect immunofluorescence assay detecting IBV S (a) or SARS-CoV S (c). The graphs show the quantification of nuclei per syncytium for IBV S (b) or SARS-CoV S (d) in the presence of DMSO or drug. (b, d) In excess of 50 syncytia were analysed in three independent experiments. The error bars represent standard deviation and P values were calculated using a paired t-test. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

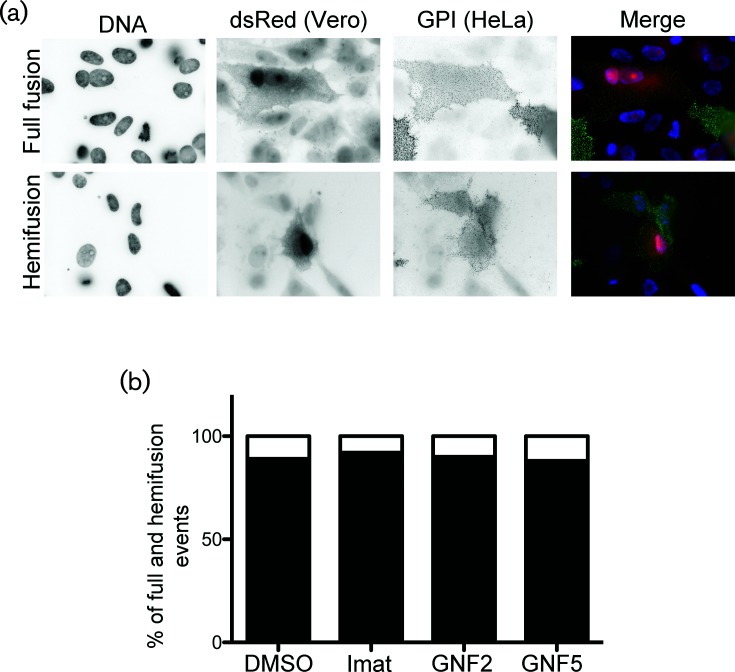

Imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 block IBV S-induced fusion prior to hemifusion

Virus fusion with host cells and virus-induced cell–cell fusion occur in two steps. Mixing of the outer membrane leaflets (hemifusion) is followed by inner leaflet mixing and complete fusion. A previous report demonstrated that imatinib inhibits HIV env-induced cell–cell fusion at a post-hemifusion step, as indicated by the accumulation of hemifusion events observed in imatinib-treated cells [18]. To determine whether imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 inhibit IBV S-induced cell–cell fusion pre-or post-hemifusion, we used a similar assay to that used for HIV to distinguish hemifusion from full fusion events. HeLa cells were transfected with one plasmid encoding IBV S and a second encoding YFP targeted to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor (YFP-GPI). After transfection, these cells were co-cultured with Vero cells transfected with a plasmid expressing soluble dsRed. Hemifusion between a HeLa and a Vero cell results in both cells containing the GPI anchor at the plasma membrane, with cytoplasmic dsRed signal only being observed in one of the two cells. Full cell–cell fusion results in both cells having cytoplasmic dsRed signal and containing the labelled GPI anchor at the plasma membrane. Fusion events were observed and categorized as full fusion or hemifusion (Fig. 6a). IBV S staining is not shown, but was used to ensure the coexpression of IBV S and YFP-GPI in HeLa cells. We observed 54 total fusion events in the control sample and 25, 20 and 24 total fusion events in samples treated with imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 samples, respectively. Hemifusion events accounted for 14 % of all fusion events from control cells, and 8 %, 11 and 12 % of those in cells treated with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5, respectively (Fig. 6b). Although the total number of fusion events in drug-treated cells was reduced as expected, treatment with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 showed no significant change in the percentage of hemifusion events as compared to control cells (Fig. 6b), suggesting that Abl kinase inhibitors block the initial hemifusion step. This result demonstrates that Abl kinase inhibitors interfere with the cell–cell fusion necessary for syncytia formation, and provides evidence that these drugs may inhibit virus–cell fusion by preventing hemifusion, the first step in membrane mixing.

Fig. 6.

Abl kinase inhibitors block cell–cell hemifusion. HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids encoding IBV S and YFP-GPI. Vero cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding dsRed. Cells were co-cultured 24 h post-transfection, −/+10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5. IBV S, YFP-GPI and dsRed were detected 24 h later. Surface IBV S (not shown) was labelled with mouse anti-IBV S and Cy5 anti-mouse IgG. Surface YFP-GPI was labelled with rabbit anti-GFP and Alexa 488 anti-rabbit IgG. (a) Fusion events were analysed and categorized as fusion (top panels) or hemifusion (bottom panels). (b) Quantification of hemifusion and full fusion events from two independent experiments. Total fusion events in control and drug-treated cells were normalized to 100 % and the percentage of hemifusion events was calculated based on comparison to total events for each treatment condition. Black and white indicates % of full fusion and hemifusion events, respectively.

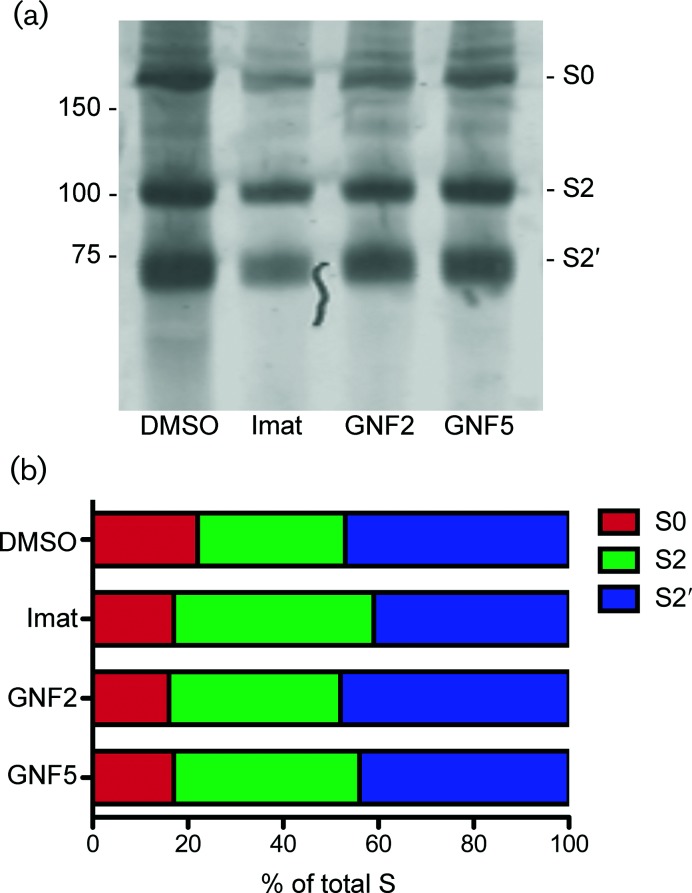

Abl kinase inhibitors do not affect IBV S processing

We considered that treatment with Abl kinase inhibitors could affect IBV S processing and that this could be the cause of the block in cell–cell fusion. The full length S protein (S0) undergoes two cleavage events necessary for cell–cell fusion to take place. The first occurs at the S1/S2 site and produces two fragments, S1 and S2 [2]. The second cleavage occurs at the S2′ site, resulting in exposure of the fusion peptide [3, 4]. In the strain of Vero cells used here, we observed that IBV S is primed for the cleavage that occurs during virion particle preparation, providing a fusion-competent virus prior to host cell receptor binding. Because exposure of the fusion peptide has been shown to be necessary for cell–cell fusion and syncytia formation, we measured the amounts of each cleavage product after treatment with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5. None of the drug treatments affected the relative amounts of S0, S2 or S2′ (Fig. 7a, b), indicating that IBV S protein processing and cleavage are not affected by Abl kinase inhibitors.

Fig. 7.

Abl kinase inhibitors do not affect IBV S processing. Vero cells were pre-treated for 1 h with DMSO or 10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 at 37 °C. Cells were adsorbed at 37 °C for 1 h with IBV at an m.o.i. of 0.1 in the presence of DMSO or drug. The cells were washed, fresh medium containing DMSO or drug was added and infection was allowed to proceed for 18 h at 37 °C. (a) A sucrose cushion was used to concentrate virus from supernatants of control and drug-treated IBV-infected cells. Concentrated virus was analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot using rabbit anti-IBV S and Licor anti-rabbit IgG 680. (b) The amount of S0, S2 and S2′ was calculated by normalizing the signal to the total amount of S within each sample. The results were confirmed in two independent experiments.

Discussion

We have demonstrated here that the Abl kinase inhibitors, imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5, reduce the viral titre of IBV by decreasing the number of cells infected, and that the first round of virus infection is inhibited. Our data showed that each of the three inhibitors prevents syncytia formation induced by IBV, as indicated by fewer nuclei per syncytium compared to infected, untreated cells. A decrease in nuclei per syncytium in IBV S- and SARS-CoV S-expressing cells treated with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 demonstrated that Abl kinase inhibitors prevent syncytia formation induced by the S protein in the absence of other viral proteins. Our results demonstrated that fusion was inhibited before the hemifusion step, prior to any lipid mixing of membranes. Additionally, we showed that cleavage of S into S2 and S2′ is not affected by imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5, suggesting that IBV S processing and cleavage is independent of Abl kinase activity. The results with specific inhibitors, GNF2 and GNF5, strongly suggest that IBV infection requires the activity of Abl1 and/or Abl2. Our previous report showed that Abl2, but not Abl1, is required for the entry of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV pseudovirions [15], and we hypothesized that the inhibition of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infection was due to a block in virus fusion with the endosome membrane. Here we show definitively that Abl kinase inhibitors block coronavirus S-mediated fusion.

Abl1 and Abl2 are part of a kinase superfamily that includes Src kinase. These proteins contain conserved N-terminal domains, Src homology domain 2 (SH2), Src homology domain 3 (SH3) and tyrosine kinase domains. Additionally, they contain an F-actin-binding domain (FABD) connected by a linker region. Abl1 contains one FABD, while Abl2 contains two. Abl kinases are involved in numerous cellular functions providing communication between cell signalling and actin cytoskeleton organization [33]. They are involved in T cell signalling [34, 35], embryonic development [9, 36] and cell migration and invasion in cancer [37, 38]. The distinct domains provide Abl kinases with the ability to act as scaffolds to facilitate the building of signalling complexes [9, 39, 40], and to regulate protein function through the phosphorylation of downstream protein targets [39]. Binding actin through the FABD directly regulates cytoskeleton dynamics [40–43] to activate the essential cellular pathways described above.

It is likely that virus–cell and cell–cell fusion induced by the coronavirus S protein use the same or a very similar mechanism. Because Abl kinase activity plays a role in cytoskeletal rearrangement [43, 44], we hypothesized that Abl kinase inhibitors act by interfering with the actin dynamics required for virus–cell and cell–cell fusion. Our hypothesis is supported on two fronts. First, cytoskeletal dynamics have been implicated in infection by several viruses [16–23]. Actin cytoskeleton rearrangement was shown to be required for infection by Coxsackievirus [16], vaccinia virus [17], human immunodeficiency virus [18, 19], variola and monkeypox [20]. These studies demonstrated that cytoskeletal rearrangement is a common mechanism that is required by many cellular processes and can be hijacked by viruses during infection, as reviewed by others [10, 45–47]. Second, Abl kinase’s role in actin cytoskeletal rearrangement is required for essential cell–cell fusion events, including but not limited to, osteoclast [48] and myoblast fusion [49, 50], during development. Actin-induced podosome-like structures are required for the fusion of osteoclasts and myoblasts, presumably to alter membrane tension [51, 52]. Interestingly, Harmon et al. [18] reported that cell–cell fusion mediated by the HIV envelope protein was inhibited by imatinib at a post-hemifusion step. We did not observe an increase in hemifusion events after the treatment of IBV-infected cells with imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5. Since we used a different virus, cell line and fusion assay, it is difficult to compare the two results. We favour the idea that virus interaction with host cell receptors induces actin rearrangements through Abl kinase activity, and that this brings cell membranes into close proximity to allow hemifusion followed by full fusion [51].

Our results demonstrate that the coronavirus membrane fusion step is blocked by Abl kinase inhibitors, as suggested by our previous report [15]. Because IBV is phylogenetically distant from SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, our results strongly suggest that Abl kinase activity and associated pathways may be involved in the membrane fusion events required for infection by all coronaviruses. Imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 have the potential to be general coronavirus inhibitors, preventing infection by most, if not all, coronaviruses. It is likely that multiple actions of Abl kinases are involved in coronavirus infection. It has already been shown that the scaffolding function of Abl1 and/or Abl2 brings the cellular proteins involved in actin dynamics together. The targets of Abl kinases are phosphorylated and activated, triggering cytoskeleton rearrangements that we hypothesize are necessary for virus fusion with the plasma membrane and subsequent entry, as well as cell–cell fusion that occurs later in infection. By keeping Abl kinases in a closed, inactive conformation, imatinib, GNF2 and GNF5 interfere with the scaffolding and kinase functions of these proteins, inhibiting the vital roles they play in coronavirus infection.

This work indicates that the proteins involved in the Abl kinase pathway are excellent targets for the development of treatments for coronavirus infections. Current studies are underway to determine the Abl kinase functions involved in coronavirus infection, as well as determining whether the activity of Abl1 or Abl2, or both kinases, is required for coronavirus infection. Further, mouse models, including that of the mouse hepatitis virus, can be used to test the in vivo antiviral effects of these drugs on coronavirus infection. The role that Abl kinases play in infection by many distinct viruses makes this pathway a prime target for use in the development of broadly acting antiviral therapeutics.

Methods

Cells and virus

Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Invitrogen/Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10 % foetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA, USA) and 0.1 mg ml−1 Normocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. The wild-type recombinant US Beaudette strain of IBV was used in all experiments [53].

Plasmids

pCAGGS/SARS-CoV S and pCAGGS/VSV G were described previously [54, 55]. Two codon-optimized plasmids encoding portions of IBV Beaudette S1 and S2 were generously provided by Helene Verhije (Department of Pathobiology, Utrecht University). A full-length, partially codon-optimized IBV S cDNA sequence was constructed in the mammalian expression vector pCAGGS as follows. Nucleotides 1–110 (numbering based on open reading frame) containing the signal sequence were PCR-amplified with EcoRI and BstxI sites from a non-codon-optimized cDNA sequence previously cloned by reverse transcription PCR using RNA from Vero cells infected with a Vero-adapted strain of IBV [32]. This same plasmid was the template for the PCR amplification of nucleotides 2956–3489 encoding the C-terminus flanked by the XmaI and XhoI sites. Nucleotides 111–1613 flanked by the BstxI and HindIII sites (and containing the RRFRR furin cleavage site between S1 and S2) were PCR-amplified from a cDNA vector containing a codon-optimized sequence of IBV S1, and nucleotides 1614–2955 flanked by the HindIII and XmaI sites were PCR-amplified from cDNA containing the codon-optimized sequence of IBV S2 [56, 57]. QuikChange mutagenesis (Agilent Genomics) was used to remove the HindIII restriction site between S1 and S2 once the amplicons had been ligated together, and the full coding sequence was confirmed by dideoxy sequencing.

Antibodies and Abl kinase inhibitors

The mouse monoclonal anti-IBV S antibody (9B1B6) recognizes the lumenal domain and was a kind gift from Ellen Collisson (Western University of Health Sciences) [58]. The rabbit polyclonal anti-IBV S antibody to the C-terminus was described previously [32], as was the rabbit polyclonal antibody to SARS S (anti-SCT) [54]. Rabbit anti-GFP (A-6455) was obtained from ThermoFisher. Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse IgG and Alexa Fluor 568 anti-rabbit IgG were obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA). Cy5 anti-mouse IgG was obtained from Jackson Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA). Imatinib (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA, USA), GNF2 and GNF5 (Selleckchem, Houston, TX, USA) were diluted in DMSO and used at 10 µM in all experiments. Imatinib causes little to no cytotoxicity in Vero cells treated with concentrations up to 100 µM [5], and we found here that GNF2 and GNF5 treatments of 50 µM for 24 h did not result in cytotoxicity in Vero cells.

IBV infection

Vero cells were seeded 5×105 per dish in 35 mm dishes on coverslips 24 h prior to infection. Cells were pre-treated for 1 h prior to infection with 10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5, or an equal volume of DMSO, in serum- and antibiotic-free medium (SF). SF medium was removed and virus was added to cells in 200 µl total volume of SF medium −/+drugs. Infections were carried out in medium containing 5 % FBS −/+drugs. After 8 or 18 h infections performed as described below, supernatants were harvested. Cellular debris was removed by a 3 min centrifugation at 2000 g, 4 °C, and used directly for plaque assays, or stored at −80 °C. For infection at an m.o.i. of 0.1 for 18 h, virus was adsorbed for 1 h at 37 °C with gentle rocking every 10 min. Virus was removed and the cells were washed with 1 ml DMEM +5 % FBS. Fresh DMEM +5 % FBS was added to cells −/+10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 and cells were incubated for 18 h at 37 °C. For infection at an m.o.i. of 2 for 8 h, cells were placed at 4 °C for 10 min, and virus was adsorbed for 1 h at 4 °C with gentle rocking every 10 min. Virus was removed and the cells were washed with 1 ml DMEM +5 % FBS. Fresh DMEM +5 % FBS was added to cells −/+10 µM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 and cells were incubated for 8 h at 37 °C.

Transient transfection

The X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was used to transiently transfect cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For all experiments, 35 mm dishes of Vero cells were transfected with 2 µg of pCAGGS/IBV S or pCAGGS/SARS-CoV S diluted into Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen/Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). Experiments were performed 24 h post-transfection unless otherwise indicated. For SARS CoV S, cells were treated for 15 min with 15 µg ml−1 trypsin at 37 °C prior to examination for syncytia formation as previously described [59].

Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were plated on coverslips in 35 mm dishes 24 h prior to infection or transfection, and infected or transfected as described above. To label total IBV S and SARS S proteins, at the indicated times post-infection or post-transfection cells were fixed with 3 % paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, permeabilized with block/perm buffer [PBS+10 % FBS, 0.05 % Saponin, 10 mM glycine, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4)] and incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (rabbit anti-IBV S diluted 1 : 500, rabbit anti-SARS S diluted 1 : 500 in block/perm buffer) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with PBS+10 mM glycine and stained with secondary Alexa Fluor antibodies (diluted 1 : 1000 in block/perm buffer) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were washed with PBS+glycine and DNA stained with Hoescht 33 258. To label cell surface IBV S, intact cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, incubated for 30 min on ice in block/perm buffer (without saponin) and incubated with mouse anti-IBV S (1 : 10) for 1 h on ice. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS, then fixed and permeabilized. Total IBV S and DNA were stained with rabbit anti-IBV S, and Hoescht 33258 as described above. Images were acquired with a Zeiss Axioscop microscope (Thornwood, NY, USA) equipped for epifluorescence with a Sensys charge-coupled device camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA), using IPLab software (Scanalytics, Vienna, VA, USA). Images are shown inverted for better visualization of the IBV S, dsRed and YFP-GPI signals.

Plaque assay

Vero cells were seeded at 5×105 per dish in 35 mm dishes 24 h prior to infection. Supernatants from infected cells were serially diluted 10−1 through 10−6 in serum-free medium. Cells were washed with serum-free medium, 200 µl of diluted virus was added to each well and adsorption was allowed to proceed for 1 h at 37 °C with gentle rocking every 10 min. Then 2× DMEM and 1.6 % agarose were mixed 1 : 1 and allowed to cool to 37 °C. Cells were washed with SF medium, and 2 ml DMEM/agarose was added to each well, and cells were incubated for 72 h at 37 °C. DMEM/agarose was removed from each well, crystal violet staining was used to visualize plaques and p.f.u. ml−1 was calculated for each sample.

Fusion assay

HeLa and Vero cells were plated 3.5×105 in 35 mm dishes 24 h prior to transfection. HeLa cells were transfected as described above with 2 µg pCAGGS-IBV S and 0.5 µg of a plasmid encoding YFP-GPI anchor (Clontech) and Vero cells were transfected with 0.5 µg of a plasmid encoding dsRed (Clontech). Twenty-four hours post-transfection, Vero cells were trypsinized and replated at 3.5×105 in 35 mm dishes on coverslips and grown for 1 h in 10 uM imatinib, GNF2 or GNF5 and an equal volume of DMSO. An equal volume of HeLa cells was then added to each well of Vero and DMSO or drug was added to maintain treatment conditions. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were placed on ice. On ice, the cells were incubated for 20 min in block/perm buffer as described previously (without saponin). A rabbit anti-GFP antibody and mouse anti-IBV S (1 : 500, 1 h on ice) were used to label surface YFP-GPI and IBV S, respectively. Cells were then fixed for 10 min in 3 % PFA at RT, and all the following steps were carried out at RT. Cells were washed with PBS and then permeabilized with block/perm buffer (0.05 % saponin). Cells were washed and Alexa Fluor 488 anti-rabbit and Cy5 anti-mouse were used for secondary labelling of YPF-GPI and IBV S, respectively. Hoechst 33 258 was used to stain DNA. All images were taken within 24 h with the same exposure as described above. Physical contact between Vero and HeLa cells was defined as an event. Each event was classified as either hemifusion or full fusion. For each treatment condition, the total events were normalized to 100 % and the hemifusion events were normalized to the total number of events.

IBV S processing analysis

Vero cells were plated 5×104 per well in 35 mm dishes and 24 h later infected with IBV at an m.o.i of 0.1. Eighteen hours post-infection, supernatants were collected and virus was concentrated by layering 1 ml of supernatant onto 2 ml of a 20 % sucrose cushion, and centrifuged for 1 h at 90 000 g and 4 °C in a TLA110 rotor. The supernatant was removed and samples were resuspended and analysed by SDS-PAGE on 4 to 12 % acrylamide gradient gels (NUPAGE, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Proteins were transferred to low-fluorescence PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore, CO, USA) and blocked for 1 h in 5 % non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) [150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.05 % Tween-20]. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti-IBVS antibody 1 : 500 in 5 % non-fat dry milk in TBST. Membranes were washed 3×5 min in TBST and then incubated at room temperature for 1 h with goat anti-rabbit IgG 680 1 : 20 000 (Licor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). Membranes were washed 3×5 min in TBST and rinsed in 1× TBS. Bands were visualized using the Licor Odyssey CLx and quantified using Image Studio software. The density of three IBV S bands, corresponding to S0, S2 and S2′, was measured and the percentage for each band was calculated from the total S for each treatment condition.

Supplementary Data

Funding information

This was supported by HHS | NIH | National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) AI118303 (J. M. S) and R01AI095569 (M. B. F).

Acknowledgements

We thank Helene Verhije (Department of Pathobiology, Utrecht University) for the kind gift of plasmids used to construct the codon-optimized IBV S, Jason Westerbeck for assembling the full-length IBV S clone and Ellen Collisson (Western University of the Health Sciences) for monoclonal anti-IBV S antibodies. We also thank Catherine Gilbert, Jason Westerbeck and Thiagarajan Venkataraman for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: Abl1, Abelson kinase 1; Abl2, Abelson kinase 2; Abl kinase, Abelson kinase; IBV, infectious bronchitis virus; MERS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; S, spike; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus.

One supplementary table is available with the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Mingo RM, Simmons JA, Shoemaker CJ, Nelson EA, Schornberg KL, et al. Ebola virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus display late cell entry kinetics: evidence that transport to NPC1+ endolysosomes is a rate-defining step. J Virol. 2015;89:2931–2943. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03398-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Millet JK, Whittaker GR. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:15214–15219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407087111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burkard C, Verheije MH, Wicht O, van Kasteren SI, van Kuppeveld FJ, et al. Coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endo-/lysosomal pathway in a proteolysis-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004502. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millet JK, Whittaker GR. Host cell proteases: critical determinants of coronavirus tropism and pathogenesis. Virus Res. 2015;202:120–134. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyall J, Coleman CM, Hart BJ, Venkataraman T, Holbrook MR, et al. Repurposing of clinically developed drugs for treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4885–4893. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03036-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaki GS, Papavassiliou AG. Oxidative stress-induced signaling pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;16:217–230. doi: 10.1007/s12017-014-8294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colicelli J. ABL tyrosine kinases: evolution of function, regulation, and specificity. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3139re6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng WH, von Kobbe C, Opresko PL, Fields KM, Ren J, et al. Werner syndrome protein phosphorylation by abl tyrosine kinase regulates its activity and distribution. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6385–6395. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6385-6395.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers EM, Spracklen AJ, Bilancia CG, Sumigray KD, Allred SC, et al. Abelson kinase acts as a robust, multifunctional scaffold in regulating embryonic morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:2613–2631. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-05-0292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khatri A, Wang J, Pendergast AM. Multifunctional Abl kinases in health and disease. J Cell Sci. 2016;129:9–16. doi: 10.1242/jcs.175521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchdunger E, Zimmermann J, Mett H, Meyer T, Müller M, et al. Inhibition of the Abl protein-tyrosine kinase in vitro and in vivo by a 2-phenylaminopyrimidine derivative. Cancer Res. 1996;56:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowley JD. Letter: a new consistent chromosomal abnormality in chronic myelogenous leukaemia identified by quinacrine fluorescence and Giemsa staining. Nature. 1973;243:290–293. doi: 10.1038/243290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heisterkamp N, Stephenson JR, Groffen J, Hansen PF, de Klein A, et al. Localization of the c-ab1 oncogene adjacent to a translocation break point in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1983;306:239–242. doi: 10.1038/306239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartram CR, de Klein A, Hagemeijer A, van Agthoven T, Geurts van Kessel A, et al. Translocation of c-ab1 oncogene correlates with the presence of a Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1983;306:277–280. doi: 10.1038/306277a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman CM, Sisk JM, Mingo RM, Nelson EA, White JM, et al. Abelson kinase inhibitors are potent inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion. J Virol. 2016;90:8924–8933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01429-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coyne CB, Bergelson JM. Virus-induced Abl and Fyn kinase signals permit coxsackievirus entry through epithelial tight junctions. Cell. 2006;124:119–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newsome TP, Weisswange I, Frischknecht F, Way M. Abl collaborates with Src family kinases to stimulate actin-based motility of vaccinia virus. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:233–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harmon B, Campbell N, Ratner L. Role of Abl kinase and the Wave2 signaling complex in HIV-1 entry at a post-hemifusion step. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000956. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas A, Mariani-Floderer C, López-Huertas MR, Gros N, Hamard-Péron E, et al. Involvement of the Rac1-IRSp53-Wave2-Arp2/3 signaling pathway in HIV-1 gag particle release in CD4 T cells. J Virol. 2015;89:8162–8181. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00469-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves PM, Smith SK, Olson VA, Thorne SH, Bornmann W, et al. Variola and monkeypox viruses utilize conserved mechanisms of virion motility and release that depend on abl and SRC family tyrosine kinases. J Virol. 2011;85:21–31. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01814-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.García M, Cooper A, Shi W, Bornmann W, Carrion R, et al. Productive replication of Ebola virus is regulated by the c-Abl1 tyrosine kinase. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:123ra24. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouznetsova J, Sun W, Martínez-Romero C, Tawa G, Shinn P, et al. Identification of 53 compounds that block Ebola virus-like particle entry via a repurposing screen of approved drugs. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2014;3:e84. doi: 10.1038/emi.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamauchi S, Takeuchi K, Chihara K, Sun X, Honjoh C, et al. Hepatitis C virus particle assembly involves phosphorylation of NS5A by the c-Abl tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:21857–21864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.666859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cluett EB, Kuismanen E, Machamer CE. Heterogeneous distribution of the unusual phospholipid semilysobisphosphatidic acid through the Golgi complex. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:2233–2240. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.11.2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hogue BMC. Coronavirus Structural Proteins and Virus Assembly. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schindler T, Bornmann W, Pellicena P, Miller WT, Clarkson B, et al. Structural mechanism for STI-571 inhibition of abelson tyrosine kinase. Science. 2000;289:1938–1942. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagar B, Bornmann WG, Pellicena P, Schindler T, Veach DR, et al. Crystal structures of the kinase domain of c-Abl in complex with the small molecule inhibitors PD173955 and imatinib (STI-571) Cancer Res. 2002;62:4236–4243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J, Adrián FJ, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Li AG, Ag L, et al. Targeting Bcr-Abl by combining allosteric with ATP-binding-site inhibitors. Nature. 2010;463:501–506. doi: 10.1038/nature08675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greuber EK, Smith-Pearson P, Wang J, Pendergast AM. Role of ABL family kinases in cancer: from leukaemia to solid tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:559–571. doi: 10.1038/nrc3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy EP, Aggarwal AK. The ins and outs of bcr-abl inhibition. Genes Cancer. 2012;3:447–454. doi: 10.1177/1947601912462126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stertz S, Reichelt M, Spiegel M, Kuri T, Martínez-Sobrido L, et al. The intracellular sites of early replication and budding of SARS-coronavirus. Virology. 2007;361:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lontok E, Corse E, Machamer CE. Intracellular targeting signals contribute to localization of coronavirus spike proteins near the virus assembly site. J Virol. 2004;78:5913–5922. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5913-5922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley WD, Koleske AJ. Regulation of cell migration and morphogenesis by Abl-family kinases: emerging mechanisms and physiological contexts. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3441–3454. doi: 10.1242/jcs.039859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Y, Comiskey EO, Dupree RS, Li S, Koleske AJ, et al. The c-Abl tyrosine kinase regulates actin remodeling at the immune synapse. Blood. 2008;112:111–119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu JJ, Lavau CP, Pugacheva E, Soderblom EJ, Moseley MA, et al. Abl family kinases modulate T cell-mediated inflammation and chemokine-induced migration through the adaptor HEF1 and the GTPase Rap1. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koleske AJ, Gifford AM, Scott ML, Nee M, Bronson RT, et al. Essential roles for the Abl and Arg tyrosine kinases in neurulation. Neuron. 1998;21:1259–1272. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80646-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith-Pearson PS, Greuber EK, Yogalingam G, Pendergast AM. Abl kinases are required for invadopodia formation and chemokine-induced invasion. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40201–40211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.147330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mader CC, Oser M, Magalhaes MA, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Condeelis J, et al. An EGFR-Src-Arg-cortactin pathway mediates functional maturation of invadopodia and breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1730–1741. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lapetina S, Mader CC, Machida K, Mayer BJ, Koleske AJ. Arg interacts with cortactin to promote adhesion-dependent cell edge protrusion. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:503–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.MacGrath SM, Koleske AJ. Arg/Abl2 modulates the affinity and stoichiometry of binding of cortactin to F-actin. Biochemistry. 2012;51:6644–6653. doi: 10.1021/bi300722t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin YC, Yeckel MF, Koleske AJ. Abl2/Arg controls dendritic spine and dendrite arbor stability via distinct cytoskeletal control pathways. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1846–1857. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4284-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Courtemanche N, Gifford SM, Simpson MA, Pollard TD, Koleske AJ. Abl2/Abl-related gene stabilizes actin filaments, stimulates actin branching by actin-related protein 2/3 complex, and promotes actin filament severing by cofilin. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4038–4046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.608117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodring PJ, Hunter T, Wang JY. Inhibition of c-Abl tyrosine kinase activity by filamentous actin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27104–27110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100559200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernández SE, Krishnaswami M, Miller AL, Koleske AJ. How do Abl family kinases regulate cell shape and movement? Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Selbach M, Backert S. Cortactin: an Achilles' heel of the actin cytoskeleton targeted by pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor MP, Koyuncu OO, Enquist LW. Subversion of the actin cytoskeleton during viral infection. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:427–439. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wessler S, Backert S. Abl family of tyrosine kinases and microbial pathogenesis. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2011;286:271–300. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385859-7.00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levaot N, Simoncic PD, Dimitriou ID, Scotter A, La Rose J, et al. 3BP2-deficient mice are osteoporotic with impaired osteoblast and osteoclast functions. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3244–3257. doi: 10.1172/JCI45843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hindi SM, Tajrishi MM, Kumar A. Signaling mechanisms in mammalian myoblast fusion. Sci Signal. 2013;6:re2. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim JH, Jin P, Duan R, Chen EH. Mechanisms of myoblast fusion during muscle development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2015;32:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shilagardi K, Li S, Luo F, Marikar F, Duan R, et al. Actin-propelled invasive membrane protrusions promote fusogenic protein engagement during cell-cell fusion. Science. 2013;340:359–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1234781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Georgess D, Machuca-Gayet I, Blangy A, Jurdic P. Podosome organization drives osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Cell Adh Migr. 2014;8:192–204. doi: 10.4161/cam.27840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Youn S, Collisson EW, Machamer CE. Contribution of trafficking signals in the cytoplasmic tail of the infectious bronchitis virus spike protein to virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:13209–13217. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13209-13217.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McBride CE, Li J, Machamer CE. The cytoplasmic tail of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein contains a novel endoplasmic reticulum retrieval signal that binds COPI and promotes interaction with membrane protein. J Virol. 2007;81:2418–2428. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02146-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McBride CE, Machamer CE. A single tyrosine in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus membrane protein cytoplasmic tail is important for efficient interaction with spike protein. J Virol. 2010;84:1891–1901. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02458-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wickramasinghe IN, de Vries RP, Gröne A, de Haan CA, Verheije MH. Binding of avian coronavirus spike proteins to host factors reflects virus tropism and pathogenicity. J Virol. 2011;85:8903–8912. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05112-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Promkuntod N, Wickramasinghe IN, de Vrieze G, Gröne A, Verheije MH. Contributions of the S2 spike ectodomain to attachment and host range of infectious bronchitis virus. Virus Res. 2013;177:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang L, Parr RL, King DJ, Collisson EW. A highly conserved epitope on the spike protein of infectious bronchitis virus. Arch Virol. 1995;140:2201–2213. doi: 10.1007/BF01323240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simmons G, Reeves JD, Rennekamp AJ, Amberg SM, Piefer AJ, et al. Characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) spike glycoprotein-mediated viral entry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.