Abstract

Background:

Acitretin is a widely used systemic retinoid in the treatment of psoriasis. Dosage of acitretin in not weight adjusted due to certain interindividual variations.

Objective:

To evaluate the clinical efficacy and effects on biochemical parameters of fixed tapering dosage of acitretin in patients with psoriasis administered over a period of 4 weeks.

Materials and Methods:

This was an observational study. The study included patients of psoriasis vulgaris in the age group of 18 and 65 years with a psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score of >10 which was not responsive to topical therapy and phototherapy. Patients were given oral acitretin daily at a dose of 25 mg BD for 2 weeks, which was later tapered to 25 mg OD for another 2 weeks. The clinical efficacy and biochemical parameters were assessed.

Results:

Out of the 18 patients, PASI 75 was achieved in 66% of the patients by the end of the third week. Significant elevations were noted in serum lipids during 4 weeks, which returned to normal limits or near baseline levels at the end of 4 weeks.

Conclusion:

Fixed tapering dose of acitretin is effective in psoriasis with minimal clinical and biochemical adverse events

KEY WORDS: Acitretin, fixed tapering dose, psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder with a population prevalence ranging from 2% to 3%.[1,2] Around 150,000 new cases of psoriasis are reported annually.[2] Psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular abnormalities, hypertension, dyslipidemia, atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and depression.[2] Treatment approaches for psoriasis range from topical therapies for milder forms of disease to phototherapy, systemic agents used in combination or in a sequential manner for severe involvement.[1]

Acitretin is a widely used systemic retinoid in the treatment of psoriasis.[3] It exerts an anti-inflammatory effect and normalizes the differentiation and decreases proliferation.[1] Though there is no consensus on the optimum effective dose of acitretin, higher doses of acitretin (50–75 mg) were found to be more effective than lower doses of 10 and 25 mg.[4,5] Improvement begins about 2 weeks after starting treatment and is maximum after about 12 weeks.[5] Moreover, a sudden interruption of acitretin therapy is not known to produce a rebound effect resulting in a flare.[4,6] Mucocutaneous adverse effects were one of the most common reasons for discontinuation of treatment, which were seen in higher incidence at doses of 50-75 mg daily.[5,7,8]

Considering the above data, the response of acitretin in patients with psoriasis and the changes in biochemical parameters were analyzed over a short period of 4 weeks in a fixed tapering dose.

Patients and Methods

This was an observational study conducted in the department of dermatology of our tertiary care center over 6 months after obtaining approval from the institute's ethics committee. Among the psoriasis patients attending our clinic or inpatient admissions, those fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Inclusion criteria were patients with chronic plaque psoriasis or psoriasis in exacerbation, of either sex in the age group between 18 and 65 years with a psoriasis area severity index (PASI) score of >10 which was not responsive to topical therapy and phototherapy. Pregnant and lactating patients, patients with chronic alcohol intake, and patients unwilling for treatment were excluded. Female patients who were post-menopausal or tubectomized or had completed their family and were willing to maintain contraception for 1 month before, during, and at least 3 years after completion of treatment were enrolled in the study.

After a detailed history, informed consent, and physical examination, a baseline PASI scoring was done. Complete blood cell counts, liver and renal function tests, and lipid profile were performed prior to the initiation of therapy. Patients were given oral acitretin daily at a dose of 25 mg BD for 2 weeks, which was later tapered to 25 mg OD for another 2 weeks. During treatment, the above tests and clinical assessment with PASI scoring were repeated every week for 4 weeks. The data were evaluated using Student's t-test. Simultaneously active topical therapy and systemic antihistamines were given to these patients.

Results

A total of 18 patients (12 males, 6 females) fulfilled the criteria and were included in the study. The age group ranged 20–50 years. Out of the total number of patients, 10 had chronic plaque psoriasis and 8 were psoriasis in exacerbation.

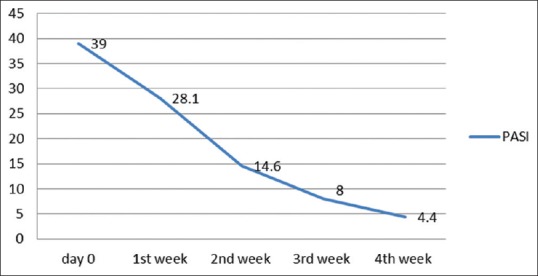

The mean baseline PASI before starting therapy was 39.00 ± 9.73. Weekly PASI score is shown in Figure 1. PASI 50 was achieved in 17 out of 18 (94%) patients by the end of the 2nd week. PASI 75 was achieved in 66% and 100% of patients by the end of the 3rd and 4th week, respectively. The types of psoriasis and PASI changes are given in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Mean PASI score over 4 weeks

Table 1.

Type of psoriasis and changes in PASI

| Type of psoriasis | Number | Average reduction in PASI after 4 weeks (%) | PASI 75 achieved (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis in exacerbation | 8 | 86.9 | 100 |

| Chronic plaque psoriasis | 10 | 85 | 100 |

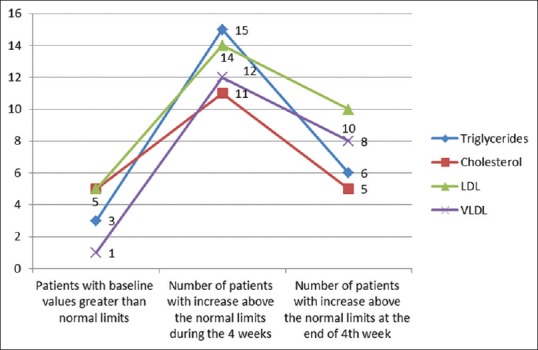

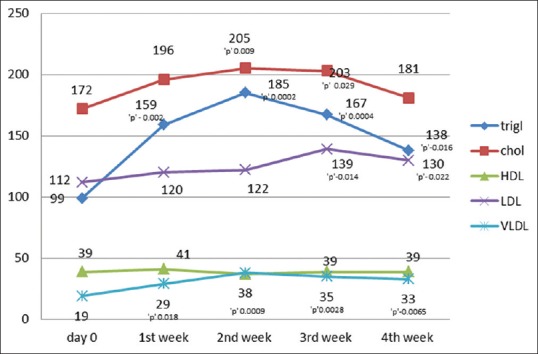

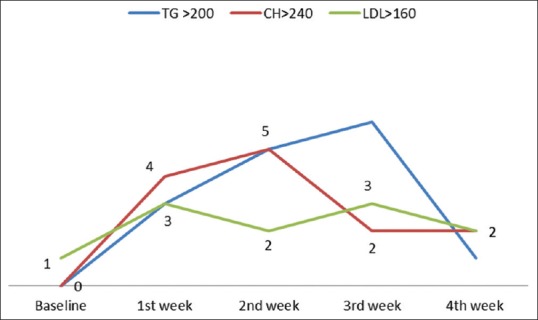

Triglyceride, cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) were increased in 100%, 83%, 61%, 83%, 100% of the cases, respectively, above the baseline levels. The changes in the above parameters with respect to the normal levels are given in Figure 2. Significant elevations were noted in triglyceride and VLDL with respect to their baseline levels in all 4 weeks with maximum changes in the 1st and 2nd week. Serum cholesterol showed a significant change with respect to the baseline value in the 2nd and 3rd week, whereas LDL changes were significant in the 3rd and 4th week [Figure 3]. Changes in blood urea on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th week were found to be significant [Figure 4]. Thirty-three percent (6 out of 18) had triglyceride levels above 200 during the course of therapy [Figure 5]. Two patients complained of cheilitis, dry mouth, and dryness of palms at the end of the 3rd week.

Figure 2.

Serum lipids with respect to normal limits

Figure 3.

Serum lipids with significance

Figure 4.

Changes in hepatic and renal parameters

Figure 5.

Weekly variation in patients with high lipid levels

Discussion

Acitretin is a synthetic retinoid and a pharmacologically active metabolite of etretinate.[5] It offers a unique role in the treatment of psoriasis because its mechanism of action is different from that of other systemic drugs.[4] Cytosolic retinoic acid binding proteins, which transports retinoic acid to the cell nucleus, is markedly elevated in psoriatic lesions as compared to nonlesional skin, indicating a greater sensitivity of skin to retinoids.[9] Compared to etretinate, dosage of acitretin in not weight adjusted because the pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and adverse reaction profile of acitretin are subject to interindividual variations.[4] Dosage ranges from a low dose of 10 and 25 mg/day to higher dose of 50 or 75 mg/day. Higher dosages are more effective but also have an increased risk of adverse reactions.[4,5] A study conducted by Murray et al. noted that 50 mg was the most effective dose and the mean effective dose was 41 mg.[10]

Acitretin is effective in all form of psoriasis, particularly in pustular and erythrodermic variety. It can be combined with other systemic agents or therapeutic modalities.[1]

There are few studies that have evaluated the short-term efficacy of acitretin in plaque psoriasis. A study that examined efficacy at 8 weeks in patients who received an initial dose of 10, 25, or 50 mg of acitretin reported a mean reduction in PASI of 61%, 79%, and 86%, respectively, in the three treatment groups as compared to 30% in the placebo group.[5,7] An 8-week trial by Gollnick et al. in 175 patients administering acitretin at 10, 25, and 50 mg daily produced a PASI 50 in 50%, 40%, and 54% of the patients, respectively.[5,11] A multicenter Nordic trial on a median dose of acitretin 40 mg per day showed 52% achieving PASI 75 and 85% achieving PASI 50 after 12 weeks[5,12] A study by Gupta et al. on low-dose acitretin on 24 patients, treated with acitretin 10 or 25 mg per day, did not lead to any improvement in skin lesions, whereas daily doses of 50 and 75 mg resulted in an improvement of at least 75% in 25% of the patients with psoriasis.[13] In our study PASI 50 was achieved in most patients by the end of the 2nd week and PASI 75 by the end of the 3rd week. This effect could be due to higher dose which was given in the first 2 weeks. Early improvement has been reported in patients with pustular psoriasis, where acitretin induces a rapid clinical response (clearance of lesions in 10 days) in up to 84% of the patients. Acitretin induced five-fold reduction in pustules after 4 weeks in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis.[14]

Diabetes mellitus, obesity, and increased alcohol intake increase the risk for hepatotoxicity and chances of developing hypertriglyceridemia. Frequent monitoring of biochemical parameters during therapy is mandated for such patients.[15] Changes in lipid levels are dose related. Studies have shown an increase in triglycerides and cholesterol in 66% and 33% of patients, respectively, and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein in up to 40% of the patients.[13,15] In our study the maximum increase was noted in the 1st and 2nd week when patients were on 50 mg of acitretin, which steadily decreased with decreasing dosage. Similar findings were noted in a study by Pearce et al.[16] Dogra et al. noticed an increase in serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels above the upper limit of normal in 7 (11%) and 12 (20%) patients, respectively.[1] Though an increase in triglycerides, cholesterol and LDL was noted above the normal limits in many patients in our study [Figures 2 and 5], more than half returned to normal limits or near baseline levels with the reduction in dosage [Figure 3]. These patients were advised on low fat diet and lipid lowering agents in case of persistent elevated levels.

Use of acitretin may cause transitory elevations in serum liver enzymes and rarely idiosyncratic hepatotoxic reaction.[13] Changes in hepatic parameters were not significant, though the patients receiving 50 mg acitretin demonstrated higher mean increases in both SGOT and SGPT than when the dose was reduced to 25 mg. Severe psoriasis with involvement of more than 10% of BSA and hyperlipidemia are independent risk factors for moderate to advanced chronic kidney disease. The mechanisms mediating renal injury in psoriasis remain unclear, however, there are data that oxidative stress and insulin resistance may mediate the lipid-induced renal damage.[17,18]

Though significant variation in blood urea was noted. It could be attributed to the physiological variations of biochemical parameters in psoriasis.

The common cutaneous side-effects include cheilitis, dry mouth, pruritus, alopecia, xerosis, peeling of skin, rash, and paronychia, which are dose related with a higher incidence at doses of 50-75 mg daily.[1,5,15] In our study, side-effects were seen in only 11% of the patients, which is probably due to faster tapering of the drug after 2 weeks.

The difference in the duration of response between various psoriasis therapies is not well established because the definitions of relapse used in various clinical studies differ. Sudden interruption of acitretin therapy is not known to produce a rebound.[4,8] In a double-blind study comparing acitretin with etretinate, patients were followed for 6 months after a 12-week treatment course. At the end of the 6-month follow-up period, 59% of acitretin and 53% of etretinate-treated patients did not relapse.[11]

The course of treatment lasted only for 4 weeks without long-term follow-up including long-term effect, relapse, and side effects. Subsequent clinical studies are needed for long-term follow-up.

Conclusion

Despite the above mentioned drawbacks, the overall data from this study suggested that an initiation of high-dose acitretin (50 mg) treatment strategy in stable psoriasis or in exacerbation (with >10% BSA) produced quick desirable results, which could be later maintained with low dose (25 mg) without much cutaneous adverse effects while maintaining the biochemical changes, majorly within the normal range. This approach may be an advantage in settings such as arresting sudden flare in psoriasis or sequential therapy. This can boost patients’ confidence, thereby increasing compliance when it is given for longer duration of time.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dogra S, Jain A, Kanwar AJ. Efficacy and safety of acitretin in three fixed doses of 25, 35 and 50 mg in adult patients with severe plaque type psoriasis: A randomized, double blind, parallel group, dose ranging study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e305–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pietrzak A, Michalak-Stoma A, Chodorowska G, Szepietowski JC. Lipid Disturbances in Psoriasis: An Update. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/535612. pii: 535612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Lernia V, Bonamonte D, Lasagni C, Belloni Fortina A, Cambiaghi S, Corazza M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of acitretin in children with plaque psoriasis: A multicenter retrospective analysis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:530–5. doi: 10.1111/pde.12940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carretero G, Ribera M, Belinchón I, Carrascosa JM, Puig L, Ferrandiz C, et al. Guidelines for the use of acitretin in psoriasis. Psoriasis group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:598–616. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ormerod AD, Campalani E, Goodfield MJ. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines on the efficacy and use of acitretin in dermatology. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:952–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menter MA, See JA, Amend WJ, Ellis CN, Krueger GG, Lebwohl M, et al. Prooceedings of the psoriasis combination and rotation therapy conference. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:315–21. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(96)80148-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lassus A, Geiger JM, Nyblom M, Virrankoski T, Kaartamaa M, Ingervo L. Treatment of severe psoriasis with etretin (RO 10- 1670) Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:333–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katugampola RP, Finlay AY. Oral retinoid therapy for disorders of keratinization: Single-centre retrospective 25 years’ experience on 23 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:267–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegenthaler G, Tomatis I, Didierjean L, Jaconi S, Saurat JH. Overexpression of cellular retinoic acid-binding protein type II (CRABP-II) and down-regulation of CRABP-I in psoriatic skin. Dermatology. 1992;185:251–6. doi: 10.1159/000247462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray HE, Anhalt AW, Lessard R, Schacter RK, Ross JB, Stewart WD, et al. A 12-month treatment of severe psoriasis with acitretin: Results of a Canadian open multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:598–602. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70091-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gollnick H, Bauer R, Brindley C, Orfanos CE, Plewig G, Wokalek H, et al. Acitretin versus etretinate in psoriasis-clinical and pharmacokinetic results of a German multicentre study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:458–68. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70198-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kragballe K, Jansen CT, Geiger JM, Bjerke JR, Falk ES, Gip L, et al. A double-blind comparison of acitretin and etretinate in the treatment of severe psoriasis - results of a Nordic multicenter study. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1989;69:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta AK, Goldfarb MT, Ellis CN, Voorhees JJ. Side-effect profile of acitretin therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:1088–93. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(89)70138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroder K, Zaun H, Holzmann H, Altmeyer P, el-Gammal S. Pustulosis palmo-plantaris. Clinical and histological changes during acitretin therapy. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1989;146(Suppl):S111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katz HI, Waalen J, Leach EE. Acitretin in psoriasis: An overview of adverse effects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:S7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearce DJ, Klinger S, Ziel KK, Murad EJ, Rowell R, Feldman SR. Low-dose acitretin is associated with fewer adverse events than high-dose acitretin in the treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1000–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.8.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joy W, Shuwei W, Kevin H, Denburg MR, Shin DB, Gelfand JM, et al. Risk of moderate to advanced kidney disease in patients with psoriasis: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trevisan R, Dodesini AR, Lepore G. Lipids and renal disease. J Am Soc Nephro. 2006;17(Suppl 2):S145–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]