Abstract

Background:

Herpes zoster (HZ) is identified to induce postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) which is difficult to cure. PHN-related pain brings patients not only physical discomfort but also mental depression and anxiety. Currently, the main purpose of PHN treatment is to reduce patients’ pain. Now treatment combining some international pain management and drug therapy has come up.

Aims and Objective:

This study aims to evaluate the effect of interventional management through meta-analysis.

Materials and Methods:

Interventional pain management was defined as a direct strategy on nerve through physical or chemical method. Drug therapy was always regarded as control. Potentially relevant articles were searched in PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library through key words by consensus. Pain severity was evaluated by a validated visual analog scale (VAS). Moreover, the weighted mean difference was used to calculate pain intensity. Some trails recorded the efficiency rate and odds ratio was used to calculate the effectiveness. Statistical heterogeneity was measured by the value of I2, and when statistical I2 > 50%, subgroup analysis was used to seek for the source of heterogeneity.

Results:

Pulsed radiofrequency (PRF) combined with medication reduced the VAS scores at 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after treatment. The nerve block combined with medication reduced VAS scores at 8 weeks after treatment, but there is no difference between the results of medication alone at 1, 2, and 4 weeks after treatment.

Conclusion:

The interventional mean of PRF combined with medication has a good effect on PHN. The effect of nerve block combined with medication on PHN seems to be the same as that of medication alone. Besides, a long period with high-quality randomized controlled trial should be done to verify the results.

KEY WORDS: Interventional pain management, meta-analysis, postherpetic neuralgia

Introduction

Herpes zoster (HZ) is an acute inflammatory skin disease caused by the reactivation of the varicella zoster virus (VZV). VZV is usually dormant and remains concealed in the sensory ganglia of cranial and spinal nerves following the resolution of chicken pox.[1] The prominent clinical phenotype of HZ invasion is a cluster of blisters accompanied with pain. The pain normally gets relieved in 1 month after the rash is completely healed. Yet, in some patients, the pain will not disappear and will last for months or years, which is called postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).[2] In spite of no unified duration, PHN is conventionally defined as dermatomal pain which lasts for 90 days and longer from the onset of the acute herpes rash.[3]

PHN is usually described as a persistent feeling of burning or stabbing. In addition, some patients develop hyperesthesia and experiance pain with light touch.[4] PHN is a common complication of HZ, and the estimation of its incidence is always associated with the study design, age distribution, and enrolled patients. Several factors can influence HZ to cause PHN. For example, age is an undoubting factor that is found in many researches. Besides, recent trials show that the prodromes and pain intensity in HZ are major potential factors for the development of PHN.[5] PHN not only impairs the quality of life (QoL) of patients but also brings a burden to the health-care system all over the world.[1,6] The allodynia is lasting and it can trigger long-term mental disorders such as depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance. This indicates that preventing PHN will play an important role in treating HZ. However, patients with HZ bear a high-risk of developing PHN, with susceptibility frequency reaching 3.9–42.0/100,000 person-years.[7] Thus, it is more necessary to find effective measures to treat PHN.

The pathogenesis of PHN is complicated. It is generally accepted as central sensitization caused by nerve inflammation, increased nerve excitability, and the change of neural plasticity.[8] Up to now, the first aim of therapy is to relieve the pain and the second aim is to relieve the symptom secondary to PHN. Apart from the primary approach of pain-relief drugs, antiepileptic drugs and antidepressant are also used as ancillary methods.[3] The antiepileptic drugs such as pregabalin can bind to L-type calcium channels to stabilize the cell membranes and inhibit the release of excitatory glutamate after central sensitization.[9] Antidepressant can block the sodium channel and inhibits reabsorption of norepinephrine, thus raising the pain threshold.[10] However, the antiepileptic drugs or antidepressant that are taken orally may result in a poor effect or cause unbearable side effects such as drug addiction, nausea, and dizziness. With it, doctors try to find interventional managements to relief PHN. Interventional pain managements mean using physical or chemical treatments to selectively affect the spinal nerves or spinal nerve roots invaded by viruses to alleviate pain.

The objective of this study was to systematically summarize the efficiency of interventional pain management in treating PHN and the mean difference of interventional pain management.

Materials and Methods

We conducted comprehensive, serial searches in order to find published studies regarding application of interventional management. We designed this systematic review according to the Cochrane review method.[11] This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses guidelines.[12]

Data sources and search strategy

With undefined study published or unpublished in all languages, we performed literature searches in databases including PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. The following mesh terms, words and combinations of words were used in constructing the systematic search: “postherpetic neuralgia/PHN”, “paravertebral,” “epidural”, “dorsal root ganglion”, “spinal nerve”, “sympathetic”, “injection”, “block”, “nerve block.” The search was unlimited by time up to May 31, 2017 and limited to trail study. Each search has no limits on language but limited with human subjects. The details of the search with PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library are shown in Box 1, 2, and 3, respectively (Supplemental material).

Study selection

Selection was performed by consensus from potentially relevant articles. Eligible studies were included in our meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with following conditions: (1) patients with no other neuropathic pain except PHN, (2) patients’ VAS >3 before treatment, (3) the treatment group received interventional pain management including nerve block with/without medical therapy or electrical nerve stimulation with/without medical therapy, and (4) a control group received either nerve block injected procedure with placebo (e.g., normal saline) or a noninterventional pain management.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction was independently performed by two authors using a prespecified data extraction form. First, reviewers extracted relevant studies from the primary pool by the title or abstract as well as full text when necessary. Second, references of relevant articles selected from the primary pool were read to find out potentially relevant studies. Finally, studies meeting the conditions were performed and recorded. When any discrepancy arose, a third author was required to review. Extracted data included study design, patient characteristics, control and characteristics of interventional pain management, follow-up time, analgesia efficiency, and the incidence of adverse reactions. The risk of bias of this study was assessed through a Cochrane risk of bias tool. The bias rating was independently performed by two authors and a third author would work to determine the results in case of any difference in the ratings.

Statistical analysis

RevMan 5.3 for Windows was used to analyze the data. Pain severity was evaluated by a validated visual analog scale (VAS). Moreover, the weighted mean difference was used to calculate pain intensity. Some trails record the efficiency rate and odds ratio (OR) was used to calculate the effectiveness. Statistical heterogeneity was measured by I2 statistic. Heterogeneity also graded by I2 set as low (<25%), medium (25%–75%), and high (≥75%) levels. When statistical I2 > 50%, it suggested that at least moderate substantial heterogeneity existed. Random effects meta-analysis method was used for analysis of the data and subgroup analysis was used to find out the source of heterogeneity. If statistical I2 < 50%, a fixed-effect model would use to analyze the data.

Results

Study identification

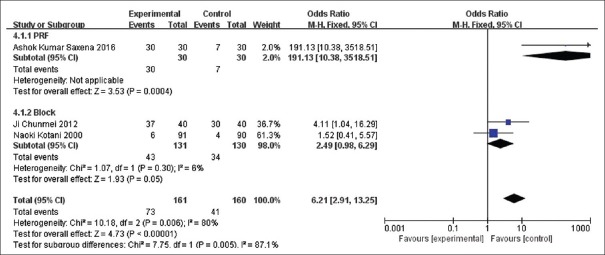

A total of 1566 articles were searched in the database through multikeyword information retrieval and 1213 studies were remained even after 352 duplicates were removed. After reading the titles and abstracts, 1205 articles were excluded because they were reviews or not meeting the previously mentioned selection criteria. Finally, 6 articles were left and read through intensively and 6 potentially relevant studies were brought into analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of retrieved, screened, and included studies

Study characteristics and patient population

Table 1 summarized the characteristics, interventions, follow-up durations, and outcome measures of included patients. The total number of the participants was 631, and sample capacity ranged from 33 to 270. There was no difference of gender ratio in four studies[13,14,15,16] and the other two studies did not make gender comparison between the intervention group and the control group.[17,18] The average age of all the participants age was above 59.

Table 1.

Basic characters of the included studies

| Author, year | Category | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| Kotani et al. 2000[13] | Interventions | A: Intrathecal methylprednisolone and lidocaine. (3 ml of 3 percent lidocaine with 60 mg of methylprednisolone acetate) B: Intrathecal lidocaine alone (3 ml of 3 percent lidocaine) C: No treatment Patients in all three groups were permitted to take the nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug diclofenac (50-mg tablets, up to four times daily) |

| Participants, n | Randomized: 277. Analyzed: 270 A/B/C: 89/91/90 |

|

| Patients characters (A/B/C) | Mean age: 63±8/65±8/65±7 Men: 53%/48%/52% Baseline pain (VAS): Each group was about 6~8. There was no statistical significance Duration of PHN (month) :6±19/41±20/38±19 |

|

| Duration of follow-up | 4 weeks, 1 year, 2 years | |

| Outcome | Burning pain (VAS), allodynia (VAS), the area of maximal pain and allodynia, global pain relief, dose of diclofenac, IL-8 | |

| Wang et al. 2012[18] | Interventions | A: Pregabalin alone (d1 75 mg, po, qn, d2~d3 75 mg, po, bid, d4 to the end 75 mg, po, tid) B: Pregabalin combined with ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral nerve block (the dose of pregabalin was same as A, 0.3% lidocaine with 10 mg triamcinolone was used to nerve block) |

| Participants, n | Randomized: 52 Analyzed: 52 A/B: 25/27 | |

| Patients characters (A/B/C) | Mean age: All patients average age were 67.2 Men: 56% in all patients Baseline pain: 7.99±1.42/7.96±1.28 Duration of PHN (month): Not mentioned |

|

| Duration of follow-up | 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12 weeks | |

| Outcome | VAS, side effect | |

| Ji et al. 2012[17] | Interventions | A: Receiving stellate ganglion block therapy (5% lidocaine 10 ml, 28 day) B: Receiving pregabalin treatment (150 mg, bid, 56 day) C: Receiving stellate ganglion block and pregabalin treatment (5% lidocaine 10 ml, 28 d+150 mg pregabalin, bid, 56 day) When VAS >7 after treatment, patients were allowed to take celebrex 200 mg, bid |

| Participants, n | Randomized: 120 Analyzed: 120 A/B/C: 40/40/40 |

|

| Patients characters (A/B/C) | Mean age: All patients average age were 63.5±13.3 Men: 60% in all patients Baseline pain: 7.59±1.24/7.64±1.11/7.61±1.25 Duration of PHN (month): Not mentioned |

|

| Duration of follow-up | 1, 2, 3, 4, 8 weeks | |

| Outcome | VAS | |

| Ke et al. 2013[14] | Interventions | A: Electrode needle punctured with PRF (the electrode needle punctured through the angulus costae of each patient guided by X-ray; PRF at 42°C for 120 s was applied after inducing paresthesia involving the affected dermatome area) B: Electrode needle punctured alone (the same procedure was also applied in this group twice without radiofrequency energy output) |

| All patients were allowed to take tramadol after their PRF treatment for pain control according to the severity of the pain | ||

| Participants, n | Randomized: 96 Analyzed: 96 A/B: 46/46 | |

| Patients characters (A/B/C) | Mean age: 73.04±6.52/71.14±7.2 Men: 54%/48% Baseline pain: 6.10±1.15/6.35±1.26 Duration of PHN (month): 23.02±15.14/25.19±15.26 |

|

| Duration of follow-up | 3, 7, 14 days, 2, 3, 6 months | |

| Outcome | VAS, SF-36 health survey questionnaire, side effects, the average of tramadol | |

| Saxena et al. 2016[15] | Interventions | A: Received pregabalin with pulsed radiofrequency (pregabalin 75 mg/150 mg, bid, 8 weeks + PRF below 42°C for 180 s) B: Controls received pregabalin with sham treatment (pregabalin 75 mg/150 mg, bid, 8 weeks + PRF sham treatment) For patients with inadequate pain relief (VAS >3/10), tablet tramadol 50 mg was dispensed |

| Participants, n | Randomized: 60 Analyzed: 60 A/B: 30/30 | |

| Patients characters (A/B/C) | Mean age: 61.33±7.96/59±7.6 Men: 56.7%/57.7% Baseline pain: 6.87±0.73/7.1±0.8 Duration of PHN (month): 4.02±1.44/3.8±1.52 |

|

| Duration of follow-up | 1, 2, 4, 8 weeks | |

| Outcome | VAS, GPE, NRS-sleep, quality of life, levels of serum BDNF, rescue analgesia | |

| Wang et al. 2017[16] | Interventions | A: PRF combined with pharmacological therapy (PRF 42°C, 120 s, and the twice treatment for a group+pharmacological therapy the same as B) B: Pharmacological therapy (only accepted diclofenac 75 milligrams (mg)/day, pregabalin 300mg/day, cobamamide 1mg/day 10 days) |

| Participants, n | Randomized: 36 Analyzed: 33 A/B: 18/15 | |

| Patients characters (A/B/C) | Mean age: 67.73±13.94/72.22±10.41 Men: 28%/33.3% Baseline pain: 6±0.82/6.08±0.79 Duration of PHN (month): Not mentioned |

|

| Duration of follow-up | 48 h | |

| Outcome | VAS, SF-Mcgill, NRS-sllep, Pain Vison PS-2100 |

VAS: Visual analog scale, PHN: Postherpetic neuralgia, PRF: Pulsed radiofrequency, BDNF: Brain Derived Neurotrophic Factor, GPE: Global Perceived Effect, NRS: Numeric rating scale

Three studies mainly discussed the efficiency of nerve block[14,15,16] and the other three studies mainly recorded the effects of pulsed radiofrequency (PRF).[13,17,18] The nerve block and PRF positions were determined by corresponding nerve locations of the painful area. Nerve block involved intrathecal block,[13] thoracic paravertebral nerve block,[18] and stellate ganglion block.[17] The PRF parameters and block injected drugs are listed in Table 1.

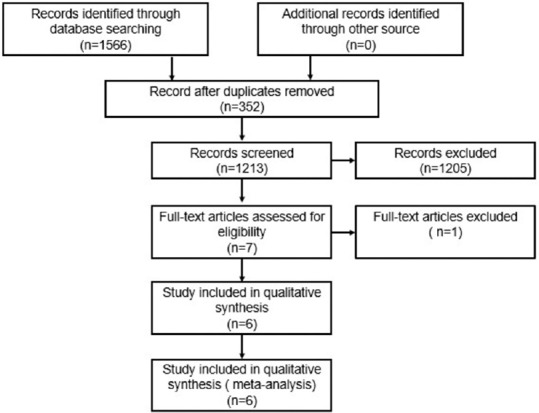

Quality of the included studies

The included studies were assessed according to the Cochrane Handbook 7 criteria. Figure 2 shows the corresponding risk of bias. All the studies meet the requirement of randomization. A half of the studies reported an allocation concealment scheme. The study of Ma Ke et al. did not specially emphasize the allocation concealment scheme, but this scheme was found to exist after reading the experiment of their article.[1]

Figure 2.

Quality evaluation of included studies

Results of Meta-analysis

Visual analog scale score analysis

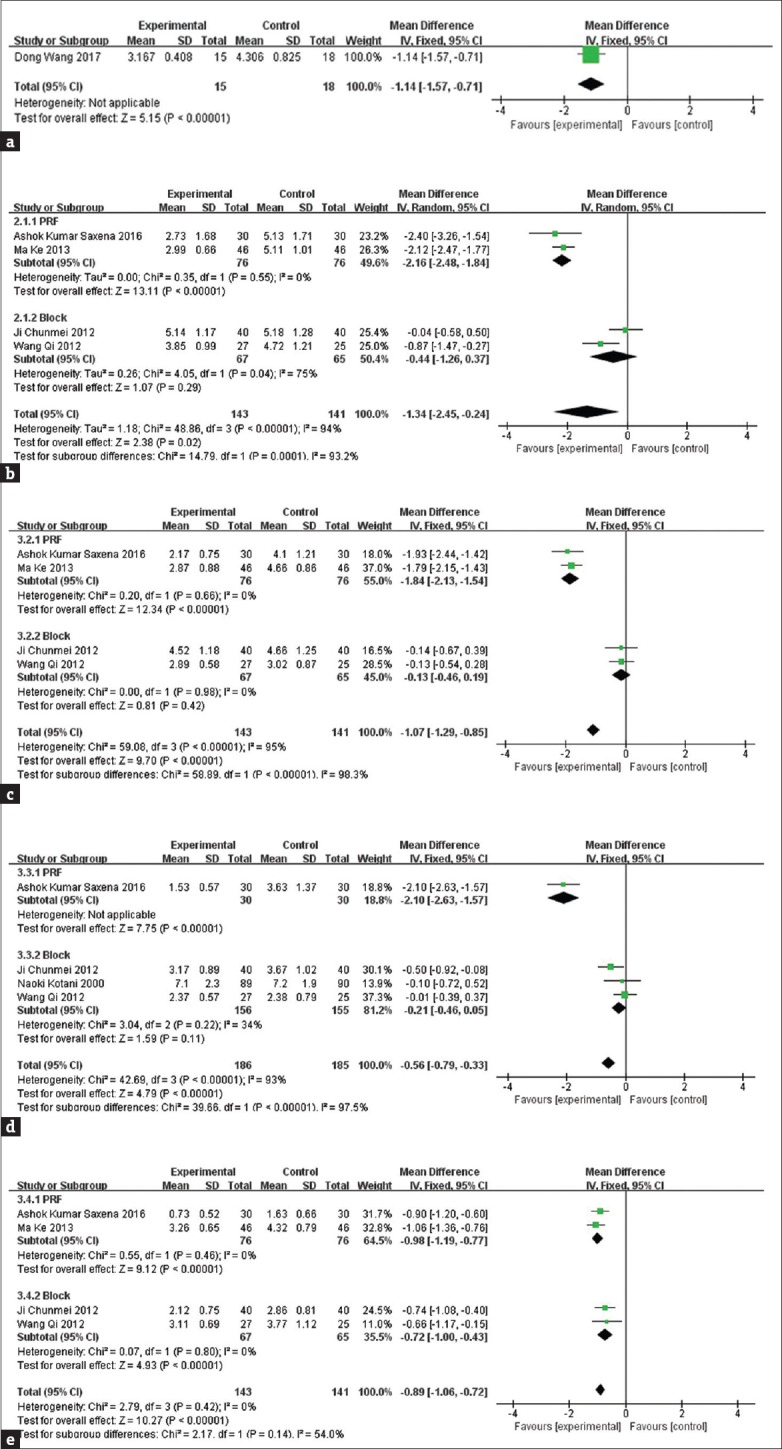

The effects of pain relief of interventional management and pharmacotherapy at 48 h, 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks (2 months are viewed as 8 week[14]) after treatment were compared according to the VAS observing time points of these studies.

Figure 3a shows the changes of VAS at the 48 h. The arrival of this result is based on one trial that uses PRF as the interventional mean. According to the result, PRF can mitigate the pain caused by PHN 48 h after the operation (MD = −1.14, 95% CI [−1.57, −0.71], P < 0.00001).

Figure 3.

The comparison of visual analog scale at 48 h (a), 1 week (b), 2 weeks (c), 4 weeks (d), 8 weeks (e)

Figure 3b shows that VAS following nerve intervention is significantly reduced in comparison with pharmaceutical therapy at 1 week after the onset of treatment. However, there is a big heterogeneity among these trials (I2 = 94%). To detect the source of heterogeneity, a subgroup analysis was conducted according to the intervention mean. The result showed that there was a small heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) between PRF intervention trials, but at the same time, a big heterogeneity (I2 = 75%) still remained in block trials. According to the outcome of subgroup analysis, PHN patients show a good therapeutic effect after PRF treatment (MD = −2.16, 95% CI [−2.84, −1.84], P < 0.00001). However, the block at 1 week seemed in vain (MD = −0.44, 95% CI [−1.26, 0.37], P = 0.29).

Figure 3c shows that VAS following nerve intervention is significantly reduced compared with pharmaceutical therapy at 2 weeks after the onset of treatment. A high heterogeneity can be found among these 4 trails (I2 = 95%), but the heterogeneity was reduced after subgrouping (PRF subgroup I2 = 0%, block subgroup I2 = 0%). The subgroup analysis found that PRF intervention alleviated PHN pain at 2 weeks after the onset of treatment (MD = −1.84, 95% CI [−2.13, −1.54], P < 0.00001), while it seemed that there was no difference between the intervention of block and the pharmaceutical treatment (MD = −0.13, 95% CI [−0.46, 0.19], P = 0.42).

Figure 3d shows that VAS following nerve intervention is significantly reduced compared with pharmaceutical therapy at 4 weeks after the onset of treatment. High heterogeneity remains among these four trails (I2 = 93%). Same as the above, subgroup analysis was carried out and the result showed that heterogeneity decreased after subgrouping (heterogeneity of the PRF subgroup was not applicable; block subgroup I2 = 34%). Moreover, it also showed that PRF intervention alleviated PHN pain at 2 weeks after the onset of treatment (MD = −2.10, 95% CI [−2.63, −1.57], P < 0.00001), but it still seemed that there was no difference between the nerve block and the pharmaceutical treatment (MD = −0.21, 95% CI [−0.47, 0.04], P = 0.1).

Figure 3e shows that VAS following nerve intervention is significantly reduced compared with pharmaceutical therapy at 8 weeks after the onset of treatment (MD = −0.89, 95% CI [−1.06, 0.72], P = 0.14). Low heterogeneity was found among these four trials (I2 = 0%). In consideration of different means of intervention, subgroup analysis was conducted as before. The same result came out, with both the PRF subgroup (MD = −0.98, 95% CI [−1.19, −0.77], P < 0.00001) and the block subgroup (MD = −0.72, 95% CI [−1.00, −0.43], P < 0.00001) showing a better pain relief effect compared with only drug treatment.

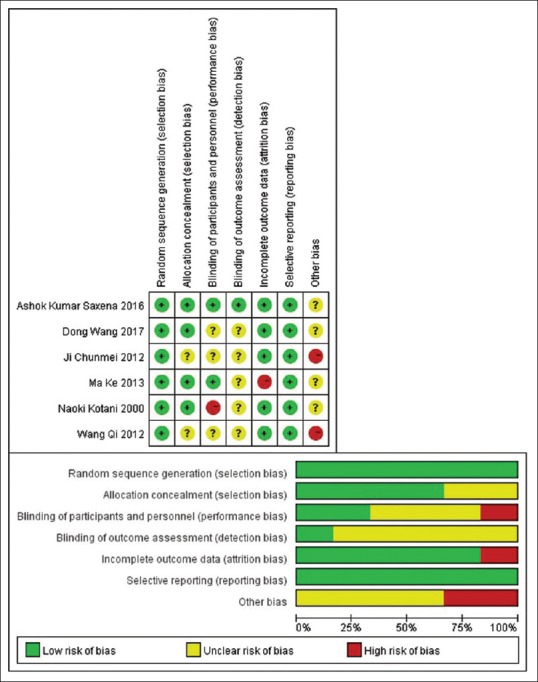

Analysis of efficiency rate

The efficiency rate was calculated in three trials.[13,15,17] High heterogeneity can be found among these three trials so that subgroup analysis was conducted. Consequently, the result was that there was no difference between the block subgroup and the control group (OR = 2.49, 95% CI [0.98, 6.29], P = 0.05), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The comparison of efficiency rate

Side effects or complications

The side effects or complications of nerve intervention and drug treatment were recorded in four trials.[14,15,17,18] Table 2 exhibits the side effects or complications of the included studies.

Table 2.

The side effects of the therapy

| Author | Description |

|---|---|

| Ji Chunmei 2012 | Dizziness and somnolence were noticed in 5 patients in control group and in 3 patients in block group. Edema was noticed in 1 patient in control group. Local hematoma was observed in 1 patients in blocked group |

| Wang Qi 2012 | Dizziness and somnolence was found in 3 patients in blocked group and 2 patients in control group. 1 patients was noticed in edema in control group |

| Ma Ke 2013 | No pneumothorax, infection, nerve injury, or postoperative paresthesia was found. Only one patient in control group was observed bradycardia. But after adjustment, the treatment was still successfully completed |

| Ashok Kumar Saxena 2016 | Somnolence was noticed in 12 patients in the control group compared with 4 in the PRF group. Dizziness was noticed in 13 patients in the control group and 14 patients in the PRF group. Local site reaction was observed in both group. Nausea and vomiting was observed in 4 patients in each group |

PRF: Pulsed radiofrequency

Discussion

Although the mechanism of PHN is not completely understood, the potential reason is the invasion of VZV which happens in the peripheral nervous system and the central nervous system. The activity of sensory afferent fibers and nociceptor were elevated due to the virus.[19] It is difficult to treat PHN, especially for the patients suffering from PHN for a long time,[3] because they bear torment mentally and burden financially.[6] To prevent HZ from leading to PHN, plenty of treatments have been conducted. HZ vaccine is used to prevent the incidence of HZ, and it can also reduce the prevalence of PHN.[20] Moreover, the application of antiviral drugs and epidural block in acute phase HZ shows the preventive effect as well.[1,21] However, once HZ develops into PHN, it will be a stubborn disease that is difficult to cure.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and central analgesics have always been used to alleviate the pain caused by PHN. However, the long-term application of analgesic could bring some side effects such as nausea dizziness and drug tolerance. To reduce the side effects of oral drugs used to treat PHN, interventional therapy was explored. After searching on these trials, it is found that the interventional management mainly includes nerve block, nerve destruction, pulsed frequency technology, and spinal cord stimulation (SCS).

Nerve block includes dorsal root ganglia block, epidural block, and spinal block. Some trials also added steroids into injected drugs, and it seemed that steroids could bring more benefits.[13] However, subsequent trials failed to replicate the results. Moreover, to prevent potentially severe complications such as arachnoiditis and fungal meningitis, safety should be considered when spinal block was used. Nerve destruction refers to destruction of the sympathetic nerve involved in the painful areas through physical methods (radiofrequency thermocoagulation) and chemical processes (ethyl alcohol and adriamycin). Seldom trials take this measure to treat PHN and only one is found.[22] Besides, the effectiveness and safety of nerve destruction have not been confirmed. PRF is the improvement of radiofrequency thermocoagulation. It came up in 1995 for the first time and then has been used as a new method to treat pain, thus rapidly spreading all over the world.[23] With the appearance of the gate-control theory, SCS has been widely used clinically to treat chronic pain.[24] Twelve trials show that SCS has an effect on PHN, but there is no strict RTC to confirm the result.[25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]

In this study, 6 eligible RCTs were found, 3 about PRF and the other 3 about nerve block. The trial conducted by Naoki Kotani[13] recorded three kinds of pain, including burning pain, lancinating pain, and allodynia. In this study, the burning pain was chosen to compare with other trials in terms of VAS. The trial conducted by Ji Chunmei[17] used nerve block in two groups. Similarly, this study made a comparative analysis on the nerve block combined with medicine group and the drug therapy group. Through the meta-analysis of the subgroup, it seemed that PRF was a good choice because the VAS at 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks after operation showed lower pain levels than the drug therapy group. Moreover, the efficiency rate of the nerve block combined with medicine group after PRF was also higher than the drug therapy group. It is usually believed that the block has a temporary pain relief effect. According to the subgroup analysis, it indeed has no effect on PHN relief at the 1, 2, and 4 weeks after nerve block, but at the 8 weeks after block, the VAS in the block group is lower than that in the drug therapy group. The potential reason is that the drug combined with the nerve block worked. No serious side effects appeared in the interventional group and the drug therapy group. The side effects or complications mentioned in the trials can be alleviated after drug withdrawal or reasonable nursing. Both PRF and nerve block are interventional methods on nerve, but their functions are different. PRF is a physical method which can induce long-term depression in the spinal cord and reversibly disrupt the transmission of impulses across small unmyelinated fibers.[37] The nerve block belongs to the chemical process, and the main medicine that acts on the nerve to inhibit pain is lidocaine. The half-life of lidocaine is around 2 h, so it is difficult for analgesia to last for a long time. Steroid mixed in lidocaine possibly contains preservatives that may lead to nerve inflammation.[38] As a result, the nerve block may not be as effective as perceived. On the other hand, since PRF is an invasive procedure, it may cause hematoma, infection and more serious conditions such as nerve damage and sensory disturbance, although this did not appear in the enrolled studies. When safety was taken into consideration, PRF is not recommended as the first choice. The first consideration for PHN is still drug therapy. The interventional managements are only considered when the drug therapy does not work well. In this situation, PRF rather than nerve block among these interventional management is recommended.

Before jumping to the conclusions, it is admitted that this study has some limitations. First, after retrieving repeatedly in the database using the key words and different search manners, many trials which used the interventional way to treat PHN could be found. However, some of these trials were not about RCT and some others did not have relevant data for analysis. Second, the number of participants included in this study was limited. Finally, the effects of intervention management and drug therapy on the QoL were not compared because although some trails recorded the QoL, the evaluated time was different. Therefore, large-scale, multiple-term, and high-quality RCTs would be necessary to prove or disprove the significant advantages or disadvantages.

Conclusion

The interventional mean of PRF combined with medication has a good effect on PHN. The effect of nerve block combined with medication on PHN seems the same as that of medication alone. Besides, long-period high-quality RCTs should be done to verify the results.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kim HJ, Ahn HS, Lee JY, Choi SS, Cheong YS, Kwon K, et al. Effects of applying nerve blocks to prevent postherpetic neuralgia in patients with acute herpes zoster: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J Pain. 2017;30:3–17. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2017.30.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2271–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson RW, Rice AS. Clinical practice. Postherpetic neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1526–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1403062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weaver BA. The burden of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in the United States. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2007;107:S2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forbes HJ, Thomas SL, Smeeth L, Clayton T, Farmer R, Bhaskaran K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia. Pain. 2016;157:30–54. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friesen KJ, Falk J, Alessi-Severini S, Chateau D, Bugden S. Price of pain: Population-based cohort burden of disease analysis of medication cost of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Pain Res. 2016;9:543–50. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S107944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain. 2014;155:654–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilden D, Nagel M, Cohrs R, Mahalingam R, Baird N. Varicella zoster virus in the nervous system. F1000Res. 2015:4. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.7153.1. pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dworkin RH, Corbin AE, Young JP, Jr, Sharma U, LaMoreaux L, Bockbrader H. Pregabalin for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60:1274–83. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055433.55136.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson CP, Vernich L, Chipman M, Reed K. Nortriptyline versus amitriptyline in postherpetic neuralgia: A randomized trial. Neurology. 1998;51:1166–71. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Green S Cochrane Collaboration. Chichester, England, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotani N, Kushikata T, Hashimoto H, Kimura F, Muraoka M, Yodono M, et al. Intrathecal methylprednisolone for intractable postherpetic neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1514–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ke M, Yinghui F, Yi J, Xeuhua H, Xiaoming L, Zhijun C, et al. Efficacy of pulsed radiofrequency in the treatment of thoracic postherpetic neuralgia from the angulus costae: A randomized, double-blinded, controlled trial. Pain Physician. 2013;16:15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saxena AK, Lakshman K, Sharma T, Gupta N, Banerjee BD, Singal A, et al. Modulation of serum BDNF levels in postherpetic neuralgia following pulsed radiofrequency of intercostal nerve and pregabalin. Pain Manag. 2016;6:217–27. doi: 10.2217/pmt.16.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D, Zhang K, Han S, Yu L. PainVision® apparatus for assessment of efficacy of pulsed radiofrequency combined with pharmacological therapy in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia and correlations with measurements. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5670219. doi: 10.1155/2017/5670219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji CM, Li XM, Sun DH, Jiang CL, Li SL. Clinical study on stellate ganglion block combined with pregabalin for treating postherpetic neuralgia at chest and back. Chin J New Drugs. 2012;21:1503–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Q, He MW, Ni JX. Effect of pregabalin combined with ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral nerve block on postherpetic neuralgia. Chin J New Drugs. 2012;21:2932–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen F, Chen F, Shang Z, Shui Y, Wu G, Liu C, et al. White matter microstructure degenerates in patients with postherpetic neuralgia. Neurosci Lett. 2017;656:152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng HF, Lewin B, Hales CM, Sy LS, Harpaz R, Bialek S, et al. Zoster vaccine and the risk of postherpetic neuralgia in patients who developed herpes zoster despite having received the zoster vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1222–31. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lapolla W, Digiorgio C, Haitz K, Magel G, Mendoza N, Grady J, et al. Incidence of postherpetic neuralgia after combination treatment with gabapentin and valacyclovir in patients with acute herpes zoster: Open-label study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:901–7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chun-Jing H, Yi-Ran L, Hao-Xiong N. Effects of dorsal root ganglion destruction by adriamycin in patients with postherpetic neuralgia. Acta Cir Bras. 2012;27:404–9. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502012000600008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richebé P, Rathmell JP, Brennan TJ. Immediate early genes after pulsed radiofrequency treatment: Neurobiology in need of clinical trials. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1–3. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar K, Abbas M, Rizvi S. The use of spinal cord stimulation in pain management. Pain Manag. 2012;2:125–34. doi: 10.2217/pmt.11.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meglio M, Cioni B, Prezioso A, Talamonti G. Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) in the treatment of postherpetic pain. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 1989;46:65–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9029-6_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abe H, Sugino N, Ohta A, Emori T, Kadota W, Mori H. Experience with the treatment of severe postherpetic neuralgia by epidural spinal cord stimulation. Hokuriku J Anesthesiol. 1995;29:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harke H, Gretenkort P, Ladleif HU, Koester P, Rahman S. Spinal cord stimulation in postherpetic neuralgia and in acute herpes zoster pain. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:694–700. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iseki M, Morita Y, Nakamura Y, Ifuku M, Komatsu S. Efficacy of limited-duration spinal cord stimulation for subacute postherpetic neuralgia. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2009;38:1004–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moriyama K. Effect of temporary spinal cord stimulation on postherpetic neuralgia in the thoracic nerve area. Neuromodulation. 2009;12:39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2009.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baek IY, Park JY, Kim HJ, Yoon JU, Byoen GJ, Kim KH, et al. Spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in patients with chronic kidney disease: A case series and review of the literature. Korean J Pain. 2011;24:154–7. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2011.24.3.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villanueva-Pérez VL, Palmisani S, Asensio-Samper JM, Fabregat-Cid G, de Andrés-Ibáñez JA. Spinal cord stimulation as a treatment for postherpetic neuralgia resistant to conventional therapy. Rev Neurol. 2011;53:190–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kapoor S. Pain management in postherpetic neuralgia: Emerging new therapeutic options besides spinal cord stimulation. Neuromodulation. 2012;15:267. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang N, Williams K. Cartographic pain data after spinal cord stimulation (SCS) neuromodulation in the setting of postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) Pain Pract. 2012;12:120. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanamoto F, Murakawa K. The effects of temporary spinal cord stimulation (or spinal nerve root stimulation) on the management of early postherpetic neuralgia from one to six months of its onset. Neuromodulation. 2012;15:151–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu MX, Zhong J, Zhu J, Xia L, Dou NN. Treatment of postherpetic neuralgia using DREZotomy guided by spinal cord stimulation. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93:178–81. doi: 10.1159/000375174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelleher L, Jassal NS, Torres B, Frye J. Efficacy of temporary spinal cord stimulation on the management of chronic postherpetic neuralgia (10276) Neuromodulation. 2016;19:e120. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi Y, Wu W. Treatment of neuropathic pain using pulsed radiofrequency: A meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2016;19:429–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rijsdijk M, van Wijck AJ, Meulenhoff PC, Kavelaars A, van der Tweel I, Kalkman CJ, et al. No beneficial effect of intrathecal methylprednisolone acetate in postherpetic neuralgia patients. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:714–23. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]