Abstract

Introduction:

Skin is one of the major target organ for adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The incidence of dermatological ADRs among indoor patients in developed countries ranges from 1–3%, whereas in developing countries such as India, it is 2–5%.

Aims:

To analyze the clinical spectrum, seriousness, outcome, causality, severity, and preventability of the cutaneous ADRs.

Material and Methods:

All cutaneous ADRs reported at the Regional Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Center between January 2013 to May 2016 were identified and evaluated. A retrospective analysis was carried out for clinical presentation, causality (as per the WHO–UMC scale and the Naranjo’a reactions (ADRs) Severity (Hartwig and Seigel scale), and preventability (Schumock and Thornton criteria) of a said drug.

Results:

Out of 2171 ADRs reported during study period, 538 were cutaneous ADRs (24.78%). The most common clinical presentation was maculopapular rash (58.92%) followed by itching (10.59%), and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (4.83%). The time relationship of cutaneous ADRs to drug therapy revealed that they can develop within 1 week to 1 year of treatment. Most common causal drug groups were antimicrobials (46%), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (18%), and antiepileptics (10%). Polypharmacy was observed in 7% of the cases. Most of the cutaneous ADRs were non-serious (91%), however, 10 were life-threatening and 1 was resulted in death due to the Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Causality category for majority of cutaneous ADRs was possible. Although majority of cutaneous ADRs were moderately severe (81%), however, not preventable (89%).

Conclusion:

The occurrence of cutaneous ADRs is common and they developed within 1 week of therapy. Antimicrobial agents and NSAIDs are the most common implicated drug class. Hence, physicians should closely monitor the patient in the first week while using such therapy for early detection and prevention of cutaneous ADRs.

KEY WORDS: Causality, cutaneous adverse drug reactions (ADRs), preventability, severity

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an adverse drug reaction (ADR) is defined as “a response to a drug that is noxious and unintended and occurs at doses, used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of a disease or for modification of physiological function.”[1] Skin is one of the major target organs for ADRs. An adverse cutaneous drug reaction is an undesirable change in the structure or function of the skin, its appendages, or mucous membranes and it encompass all adverse events related to drug eruption, regardless of the etiology.[2] The incidence of dermatological ADRs among indoor patients in developed countries ranges from 1–3%,[3,4] whereas in developing countries such as India, it is 2–5%.[5] In many countries, ADRs rank among the top 10 leading causes of mortality and India is one of them.[6] Drug eruptions are among the most common cutaneous disorders encountered by the dermatologist.[2] There is a wide spectrum of cutaneous ADRs varying from transient maculopapular rash to toxic epidermal necrolysis.[7]

Early detection, evaluation, and monitoring of ADRs are essential to reduce harm to the patients and thus improve public health. So the present study was undertaken to analyze the clinical spectrum of cutaneous ADRs and assess their seriousness, outcome, causality, severity, and preventability of the cutaneous ADRs.

Material and Methods

A retrospective analysis was carried out at the Department of Pharmacology, BJ Medical College, a recognized Adverse Reaction Monitoring Center (AMC) and regional training center under the Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PVPI). The suspected ADRs were diagnosed by treating consultants and relevant details of each ADR were collected in spontaneous ADR reporting form. Each ADR report was sent to the National Coordinating Center (NCC) via “Vigiflow.” Details of each report were also simultaneously entered in the Microsoft Excel sheet. All cutaneous ADRs reported between January 2013 to May 2016 were identified from this database.

Data were analyzed to see the total number of ADR, clinical presentation of cutaneous ADRs, time relationship between the events, and the initiation of drug treatment. An analysis was also done to see the causal drug groups, suspected drugs and their routes of administration, other concomitant conditions, and the number of drugs prescribed i.e., polypharmacy. Causality assessment was done using the WHO–UMC scale and Naranjo's algorithm.[8,9] Severity was assessed using modified Hartwig and Seigel[10] while preventability was assessed using modified Schumock and Thornton scale.[11]

Results

A total 2171 ADRs were reported between January 2013 to May 2016 at the Regional Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Center. Out of which total 538 (24.78%) were cutaneous ADRs.

The mean age of patients suffering from cutaneous ADRs was 33 ± 3 years and maximum no of cutaneous ADRs was reported in the age group of 18–35 years (46.28%) followed by 36–65 years (32.15%) and 1–12 years (10.59%). Men (55.2%) were more affected than women (44.8%).

Clinical presentation of cutaneous ADRs

Different clinical presentations of cutaneous ADRs were observed. The most common was maculopapular rash (58.92%) followed by itching, burning of the skin (10.59%), and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (04.83%). Others cutaneous ADRs were alopecia, hyperpigmentation, injection site reaction, dryness of the skin and mucous membrane, photosensitivity reaction, hypersensitivity reaction, toxic epidermal necrolysis, fixed drug eruptions, and urticaria [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical presentation of cutaneous ADRs with their frequency

| Clinical presentation of cutaneous ADRs | Total no. | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maculopapular rash | 317 | 58.92 |

| Itching, burning, or redness | 57 | 10.59 |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | 26 | 4.83 |

| Fixed drug eruption | 19 | 3.53 |

| Urticaria | 19 | 3.53 |

| Alopecia | 15 | 2.79 |

| Hyperpigmentation | 11 | 2.04 |

| Injection site reaction | 10 | 1.86 |

| Dryness of skin, mucous membrane | 8 | 1.49 |

| Dermatitis | 6 | 1.12 |

| Vesiculobullous rash | 6 | 1.12 |

| Acneiform eruptions | 5 | 0.93 |

| Erythema multiforme | 4 | 0.74 |

| Photosensitivity reaction | 4 | 0.74 |

| Red discoloration of the skin | 4 | 0.74 |

| Angioedema | 3 | 0.56 |

| Hirsutism | 3 | 0.56 |

| Papular eruption | 3 | 0.56 |

| Thrombophlebitis | 3 | 0.56 |

| Vitiligo | 3 | 0.56 |

| Hypersensitivity reaction | 2 | 0.37 |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | 2 | 0.37 |

| Worsening of existing skin lesion | 2 | 0.37 |

| Erythema nodosum | 1 | 3.13 |

| Hypopigmentation of skin | 1 | 0.19 |

| Ichthyosis on upper limb and lower limb | 1 | 0.19 |

| Pallor and weakness | 1 | 0.19 |

| Redman syndrome | 1 | 0.19 |

| Swelling of the hand | 1 | 0.19 |

| Total | 538 | 100 |

Time relationship of cutaneous ADRs with drug treatment

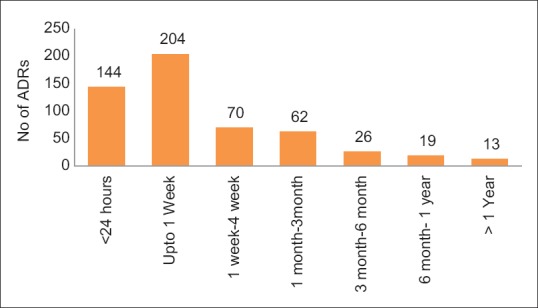

Majority of the cutaneous ADRs were reported within 1 week of starting drug treatment. Amongst them, majority of the cutaneous ADRs were observed within 24 h of treatment (26.7%). However, cutaneous ADRs were also observed within 1 month to 1 year of treatment [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Time relationship of cutaneous ADRs with drug treatment (n = 538)

The most common cutaneous ADRs reported within first 24 h were injection site reaction, angioedema, and rash, while thrombophlebitis, urticaria, and fixed drug eruption were seen within 1 week and Stevens–Johnson syndrome was observed within 1 month to 3 months of starting therapy. Interestingly, cutaneous ADRs like skin pigmentation, hair fall, and hirsutism were reported from 3–6 months of starting drug treatment [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

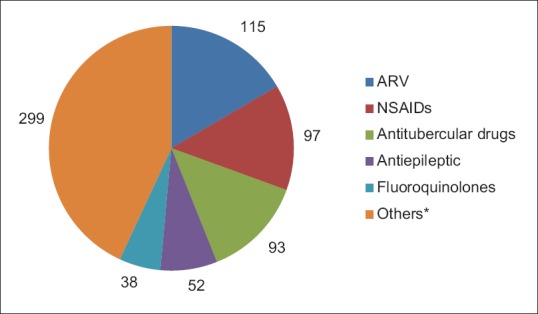

Suspected drug groups causing cutaneous adverse drug reactions (n = 694). ARV: Antiretroviral, NSAIDs: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. (*Others: B lactams, cephalosporin, corticosteroid, B lactams + b lactamase inhibitor, blood products, antidepressant, sulfonamide + DHFR inhibitor, antiamoebic, antiacne, hematinics, antimalarial, anticholinergic, aminoglycosides, glycopeptide antibiotic, vaccine, antifungal, DMARDs, immunosuppressant, macrolides, NSAIDs + NSAIDs, unknown drug, vitamins/minerals, antiviral, fluoroquinolones + antiamoebic, antileprosy, anticancer, antidiabetic, lincosamides, sulfonamides, tetracycline, B blocker, antacid)

Causal drug groups

A total 694 drugs were responsible for 538 cutaneous ADRs. The most common causal drug groups were antimicrobials (45.72%) followed by NSAIDs (18.02%) and antiepileptics (9.66%). Among antimicrobial group, antiretroviral, antitubercular, and fluroquinolones were the most common causal drug groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Details of clinical presentation of cutaneous ADRs (n=538)

| Duration | Adverse drug reactions |

|---|---|

| <24 h | Maculopapular rash, injection site reaction, angioedema |

| Upto 1 week | Fixed drug eruption, thrombophlebitis, dryness of skin, urticaria |

| 1 week to 4 weeks | Erythema multiforme, SJ syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, photosensitivity reaction |

| 1 month to 3 months | SJ syndrome, hair fall, skin discoloration, fixed drug eruption |

| 3 months to 6 months | Skin pigmentation, hair fall, hirsutism |

| 6 months to 1 year | Rash, dryness of skin |

| >1 year | Rash |

Surprisingly, the most common drugs causing cutaneous ADRs in NSAIDs group was paracetamol followed by diclofenac. In antimicrobial group, the most common suspected drugs were rifampicin followed by isoniazid, nevirapine, norfloxacin, ofloxacin, metronidazole, and fixed dose combinations like zidovudine + lamivudine + tenofovir and tenofovir + lamivudine + efavirenz.

Outcome of cutaneous ADRs

Out of 538 cutaneous ADRs, 352 cutaneous ADRs were continuing at the time of reporting. While 62 were recovering and 93 had recovered. Unfortunately, six cutaneous ADRs recovered with sequels and one was fatal.

Causality assessment, severity, and preventability

Majority of cutaneous ADRs were categorized as possible (54.61%) followed by probable (45.38%) as per the Naranjo's algorithm. While WHO–UMC causality assessment showed maximum possible relationship (65.56%) with drugs followed by probable (32.99%).

Majority of the cutaneous ADRs were moderately severe (378, 81.2%) while 90 were mild and 11 were severe in nature. Although majority of the cutaneous ADRs were not preventable (88.90%), 106 (11.10%) were preventable.

Miscellaneous

Majority of the drugs were administered orally (79.10%) followed by injectable (13.54%) and topical (5.90%). Polypharmacy i.e., more than five drugs per patient was observed in 38 (7.06%) cases. However, majority of the cutaneous ADRs were non-serious (90.89%) in nature. While 34 patients required prolonged hospitalization, 4 patients required intervention to prevent permanent damage, 10 cutaneous ADRs were life-threatening, and 1 resulted in death due to Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

Discussion

This study focused on the pattern of cutaneous ADRs reported at the regional ADR Monitoring Center. The reporting rate of cutaneous ADRs in our study was 24.78% with male preponderance. Maculopapular rash was most common clinical presentation and majority of cutaneous ADRs were reported within 1 week of starting therapy. The common causal drug group was antimicrobials followed by NSAIDs administered by oral route. Most of the cutaneous ADRs were non-serious and continuing at the time of reporting. A substantial number of cutaneous ADRs were mild in severity and not preventable.

The reporting rate of cutaneous ADRs was 24.78% in this study which is similar to study done by Ghosh et al. (25.8%).[12] In our study male were more affected than female which was similar to the study of Sharma et al.[13] However, in other studies females were commonly affected[14] or both are equally affected.[15] These differences may be due to different health care seeking patterns in various regions. In this study, cutaneous ADRs were most commonly found in the age group of 18–35 years followed by 36–65 years. Almost similar results were found in a study from a South Indian hospital, the majority of patients experiencing cutaneous ADRs were in the age group of 21–39 years followed by 40–60 years.[16]

In the present study, commonest encountered cutaneous ADR was maculopapular rash followed by itching which is similar to a study done by Gohel et al.[6] [Table 3] and Sushma et al.[17] In other studies, fixed drug eruption, acneiform eruption, and urticaria were commonly encountered cutaneous ADRs.[7] In our study, 26 cases of Stevens–Johnson syndrome were reported which was much higher than other studies.[6,18] As the study center is the Regional ADR Monitoring Center (AMC) recognized by the PVPI, training sessions were conducted for reporting of ADRs so there might be more awareness for reporting of ADRs among health care workers, and patients with serious ADRs were referred to our center from periphery which could be a reason for more cases of Stevens–Johnson syndrome. It developed mostly within 1 to 3 months of taking suspected medication, similar results were found by Patel et al.[19] Other cutaneous ADRs developed within a week of taking suspected medication in the present study, similar results found by Hotchandani et al.[20] This is because most of the skin reactions are immunological in nature and it emphasizes on close vigilance in the first week of starting therapy although few cutaneous ADRs developed after 6 months too.

Table 3.

Comparison of our study with similar other studies

| Our study (2016) | Krishna et al.[7] (2015) | Gohel et al.[6] (2014) | Padmavathi et al.[22] (2013) | Anjaneyan et al.[18] (2013) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of CADRS | 1. Rash | 1. Fixed drug eruptions | 1. Rash | 1. Fixed drug eruption | 1. Itching |

| 2. Itching or burning | 2. Acne | 2. Pruritus | 2. Maculopapular rash | 2. Rash | |

| 3. SJ syndrome | 3. Urticaria | 3. Urticaria | 3. Urticaria | 3. Swelling | |

| Causal drug groups | 1. Antimicrobials | Not done | 1. Antimicrobials | 1. Antimicrobials | 1.Antimicrobials |

| 2. NSAIDs | 2. NSAIDs | 2. NSAIDs | 2. NSAIDs | ||

| 3. Antiepileptic | 3. Not mentioned | 3. Unknown | 3. Antiepileptic | ||

| Causality | |||||

| 1. WHO-UMC | Not done | 21% | |||

| ‑Possible | 65.56% | 17.4% | 54.64% | 70% | |

| ‑ Probable | 32.99% | 52.4% | 36.08% | ||

| 2. Naranjo’s score | |||||

| ‑Possible | 54.61% | Not done | 21.65% | 22% | Not done |

| ‑Probable | 45.38% | 74.23% | 78% | ||

| Severity | |||||

| ‑Mild | 18.58% | 30.4% | 2% | 41.5% | Not done |

| ‑Moderate | 81.2% | 65.3% | 98% | 58.5% | |

| ‑Severe | 0.18% | 4.3% | 0 | 0 | |

| Preventability | |||||

| Definitely | – | 43.5% | 72.15% | 12.2% | Not done |

| Probably | 11.10% | 30.4% | 27.84% | – | |

| Not preventable | 88.90% | 26.1% | – | 87.8% |

In our study, antimicrobials were the common causal drug group followed by NSAIDs and antiepileptics. Anjaneyan et al.[18] study showed that antimicrobials, NSAIDs, and antiepileptic drugs were most prominent group of drugs responsible for cutaneous ADRs [Table 3]. Antimicrobial and NSAIDs are commonly prescribed by the physicians and general practitioners and sometimes irrationally used. Antimicrobials like antiretroviral and antitubercular drugs were more involved in developing cutaneous ADRs in the present study which was different finding from other studies.[12] The integration of National Pharmacovigilance Program in Public Health Programs (Revised National Tuberculosis and Control Program and National AIDS Control Organization) has increased reporting of ADRs due to antitubercular and antiretroviral drugs. Paracetamol is commonest suspected drug causing cutaneous ADRs as in a study done by Gohel et al.

[6] The reason behind this might be that paracetamol is most commonly prescribed concomitant medication. This is alarming as it is consumed as over-the-counter drug and generally considered as safe. We also observed polypharmacy in our study. It was one of the risk factor for developing cutaneous ADRs. Most of the cutaneous ADRs were non-serious in the present study. Similar results were found by Shah et al.[21] and Gohel et al.[6] As most of the cutaneous ADRs were rash and itching which can be managed without hospitalization.

In this study most common causality assessment was possible followed by probable in nature according to the Naranjo's and WHO–UMC criteria. But in other studies probable relationship is more than possible[6,7,21,22] [Table 3]. This may be due to use of combination drugs like antiretrovirals, antitubercular and to use of polypharmacy where assessment is difficult. Most of the cutaneous ADRs were moderately severe according to modified Hartwig and Seigel scale in the present study. Similar results were also reported by Padmavathi et al.[22] This is because in most of the reactions we have to stop the suspected drug to prevent permanent damage. According to modified Schumock and Thorton scale most of the cutaneous ADRs were not preventable. This is also observed by other studies.[12,13] Possible reason for these is cutaneous ADRs are type B reactions and are immunological in nature.

Limitations

The limitation of the study was that exact incidence of cutaneous ADRs could not be ascertained because it was spontaneous method of ADR reporting. Underreporting, lack of information about substituted drugs or treatment of ADRs, lack of information on recently introduced drugs, and single center were also other limitations of this study.

Conclusion

The occurrence of cutaneous ADRs is common and they developed within 1 week of therapy. Antimicrobial agents and NSAIDs are the most common implicated drug class. Hence, physicians should closely monitor the patient in the first week while using such therapy for early detection and prevention of cutaneous ADRs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Geneva. World Health Organization; 2002. World Health Organization. Safety of medicines - A guide to detecting and reporting adverse drug reactions-Why health professionals need to take actions. [last accessed on 2018 Oct 23]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Jh2992e/6.html .

- 2.Nayak S, Acharjya B. Adverse cutaneous drug reaction. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:2–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.39732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bigby M. Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:765–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig KS, Edward WC, Anthony AG. Cutaneous drug reactions. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:357–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noel MV, Sushma M, Guido S. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients in a tertiary care centre. Indian J Pharmacol. 2004;36:292–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gohel D, Bhatt SK, Malhotra S. Evaluation of dermatological adverse drug reaction in the outpatient department of dermatology at a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pharm Pract. 2014;7:42–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishna J, Babu GC, Goel S, Singh A, Gupta A, Panesar S. A prospective study of incidence and assessment of adverse cutaneous drug reactions as a part of pharmacovigilance a rural northern Indian medical school. IAIM. 2015;2:108–15. [Google Scholar]

- 8.The use of the WHO–UMC system for standardised case causality assessment. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 15]; Accessed from: http://www.WHO-UMC.org/graphics/4409.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schenelder PJ. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:2229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schumock GT, Thornton JP. Focusing on the preventability of adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm. 1992;27:538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghosh S, Acharya LD, Rao PGM. Study and evaluation of various cutaneous adverse drug reaction in Kasturba Hoapital, Manipal. Indian J Pharma Sci. 2006;68:212–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shama VK, Shethuram G, Kumar B. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions: Clinical pattern and causative agents, a 6 year series from Chandigarh. India. J Postgrad Med. 2001;47:95–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee S, Ghosh AP, Barbhuiya J, Dey SK. Adverse cutaneous drug reactions: A one-year. survey at a dermatology outpatient clinic of a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38:429–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saha A, Das NK, Hazra A, Gharami RC, Chowdhury SN, Datta PK. Cutaneous adverse drug recation profile at tertiary care teaching hospital of outpatients setting in Eastern India. Indian J Pharmacol. 2012;44:792–97. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.103304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pudukadan D, Thappa DM. Adverse cutaneous drug reactions: Clinical pattern and causative agents in tertiary care center in South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:20–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sushma M, Noel MV, Ritika MC, James J, Guido S. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions: A 9- year study from a South Indian hospital. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:567–70. doi: 10.1002/pds.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anjaneyan G, Gupta R, Vora RV. Clinical study of adverse cutaneous drug reactions at a rural based tertiary care centre in Gujarat. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2013;3:129–36. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel TK, Bharvaliya MZ, Sharma D, Tripathi C. A systemic review of the drug induces Stevens-Johnson syndrome and tocic epidermal necrolysis in Indian populations. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol. 2013;79:389–98. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.110749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotchandani SC, Bhatt JD, Shah MK. A prospective analysis of drug-induced acute cutaneous reactions reported in patients at a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42:118–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.64487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah SP, Deasi MK, Dikshit RK. Analysis of cutaneous adverse drug reactions at tertiary care hospital – A preospective study. Trop J Pharm Res. 2011;10:517–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padmavathi S, Manimekalai K, Ambujam S. Causality, severity and preventability assessment of adverse cutaneous drug reaction: A prospective observational study in a tertiary care hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2765–67. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/7430.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]