Abstract

Background

Hallucinations are transmodal and transdiagnostic phenomena, occurring across sensory modalities and presenting in psychiatric, neurodegenerative, neurological, and non-clinical populations. Despite their cross-category occurrence, little empirical work has directly compared between-group neural correlates of hallucinations.

Methods

We performed whole-brain voxelwise meta-analyses of hallucination status across diagnoses using anisotropic effect-size seed-based d mapping (AES-SDM), and conducted a comprehensive systematic review in PubMed and Web of Science until May 2018 on other structural correlates of hallucinations, including cortical thickness and gyrification.

Findings

3214 abstracts were identified. Patients with psychiatric disorders and hallucinations (eight studies) exhibited reduced gray matter (GM) in the left insula, right inferior frontal gyrus, left anterior cingulate/paracingulate gyrus, left middle temporal gyrus, and increased in the bilateral fusiform gyrus, while patients with neurodegenerative disorders with hallucinations (eight studies) showed GM decreases in the left lingual gyrus, right supramarginal gyrus/parietal operculum, left parahippocampal gyrus, left fusiform gyrus, right thalamus, and right lateral occipital gyrus. Group differences between psychiatric and neurodegenerative hallucination meta-analyses were formally confirmed using Monte Carlo randomizations to determine statistical significance, and a jackknife sensitivity analysis established the reproducibility of results across nearly all study combinations. For other structural measures (28 studies), the most consistent findings associated with hallucination status were reduced cortical thickness in temporal gyri in schizophrenia and altered hippocampal volume in Parkinson's disease and dementia. Additionally, increased severity of hallucinations in schizophrenia correlated with GM reductions within the left superior temporal gyrus, right middle temporal gyrus, bilateral supramarginal and angular gyri.

Interpretation

Distinct patterns of neuroanatomical alteration characterize hallucination status in patients with psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases, suggesting a plurality of anatomical signatures. This approach has implications for treatment, theoretical frameworks, and generates refutable predictions for hallucinations in other diseases and their occurrence within the general population.

Funding

None.

Keywords: Hallucination, Structural MRI, Transdiagnostic, Meta-analysis, Systematic review, Psychiatric, Neurodegenerative

Research in context

Evidence before This Study

There is increasing recognition that hallucinations occur beyond the archetype of schizophrenia, presenting in other psychiatric disorders, neurological and neurodegenerative conditions, and among the general population. Not only are hallucinations a transdiagnostic phenomenon, but also the subjective experience of hallucinating is diverse, varying in modality, content, frequency, and affect. It has been suggested that no one type of hallucination is pathognomic to any one disorder, but rather that hallucinations may exist on a spectrum from health to illness, epidemiologically or experientially continuous between individuals who do and do not meet criteria for a mental illness. However, limited research has been done to directly compare the underlying neuroanatomy of hallucinations between different disorders. With this aim, we conducted a meta-analysis and systematic review of structural MRI studies comparing individuals who experience hallucinations with those who do not, to investigate the brain morphology related to the transdiagnostic presentation of hallucinations. We searched PubMed and Web of Science with no start date limit, up to May 2018, using the keyword combination (hallucinat*) AND (MRI OR magnetic resonance imaging OR morphology OR voxel?based OR morphometr* OR neural correlate OR structur*). We included only studies with a within-diagnosis no-hallucination control to tease out structural changes specific to hallucinations from effects of the broader pathology. Neuroimaging meta-analyses were conducted on studies performing whole-brain voxelwise gray matter differences, while studies assessing other structural correlates were qualitatively synthesized.

Added Value of this Study

This is the first meta-analysis to illustrate the brain structural correlates of hallucination occurrence derived from T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a comparative manner across clinical groups. We identified two distinct gray matter substrates for hallucination presence in psychiatric compared to neurodegenerative diseases, which we hypothesize constitute at least two distinct mechanisms. In addition, we qualitatively assessed other structural neuroimaging studies over a variety of morphometric indices. We therefore provide a complete characterization of current knowledge of the brain morphology associated with hallucinations across clinical status and modality.

Implications of all the Available Evidence

Our findings show at least two structural substrates that link to the hallucinatory experience. This informs theoretical work on hallucinations which have to date been limited in generating unifying direction-specific predictions of brain structure and function. Understanding the plurality of anatomical signatures of hallucinations may also inform treatment strategies. We predict that other disorders in which patients experience hallucinations can be categorized by our approach based on the broader phenotype; for example, hallucinations in personality disorder may be of the psychiatric type, and similarly for early onset hallucinations in the general population, whilst later onset will be neurodegenerative. Moreover, by differentiating the mechanisms of hallucinations we recommend the contextualizing of research by the appropriate phenotype.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Hallucinations are transdiagnostic and transmodal perceptions of stimuli that do not exist in the physical world [1]. They are prevalent in both psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia (60–80%) [2] and bipolar disorder (BD 10–23%) [3], and neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson's disease (PD; 22–38%) [4], dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB; 80%) [5], and Alzheimer's disease (AD; 13–18%) [6], as well as in other psychiatric and neurological disorders, and among the general population (4.5–12.7%) [7]. Irrespective of diagnosis, the presence of hallucinations marks an increased risk of adverse outcomes, such as reduced likelihood of recovery in schizophrenia [8], more severe cognitive deficits in PD [9], increased mortality in AD [10], increased suicidal behaviour in adults with psychosis [11], and transition to later mental illness in children and young adults [12], [13]. Although hallucinations are often distressing, they may also be benign or contribute to meaningful personal experiences [14], [15].

Historically, hallucinations were considered a cardinal symptom of schizophrenia, but they are not pathognomic: one-third of patients do not hallucinate [2], and the experience is often heterogeneous among those who do [1]. This has been confirmed across clinical and non-clinical populations, revealing diverse phenomenology involving modality, content, affect, onset, and frequency [1], [15], [16]. Inter-individual differences among hallucinations prompt a number of conceptual, mechanistic, and clinical questions: Does phenomenological heterogeneity translate into neurobiological plurality? How would this influence theoretical models of hallucinations and inform treatments? Does the epidemiological and experiential diversity of hallucinations reflect a continuum model, in which symptoms like hallucinations are distributed over a spectrum of individuals who do and do not meet criteria for mental illness, and thus arise from a common mechanism instantiated to different degrees of severity [17]? Establishing the validity of this conceptual framework against alternatives is important for how we understand and treat hallucinations.

Despite the plurality of hallucinations, there is little empirical work comparing between-group neural correlates of hallucinations. Prior reviews and meta-analyses on the brain structural and functional correlates of hallucinations have generally limited their scope to a single diagnosis or modality [18], [19], [20], or both [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. Only two reviews have investigated hallucinations transdiagnostically or in more than one modality: one without quantitative meta-analytic comparison [26], the other focussed on acute functional correlates of hallucinations [27]. Two meta-analyses have explored the structural correlates of hallucinations, but assessed correlates of hallucination severity rather than presence/absence, and limited their scope to auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) in schizophrenia [23], [24]. We therefore planned meta-analyses to evaluate MRI-derived volumetric structural gray matter (GM) correlates of hallucination status across populations, complemented with a comprehensive review of other structural measures, including cortical thickness, gyrification, and structure-specific morphometrics.

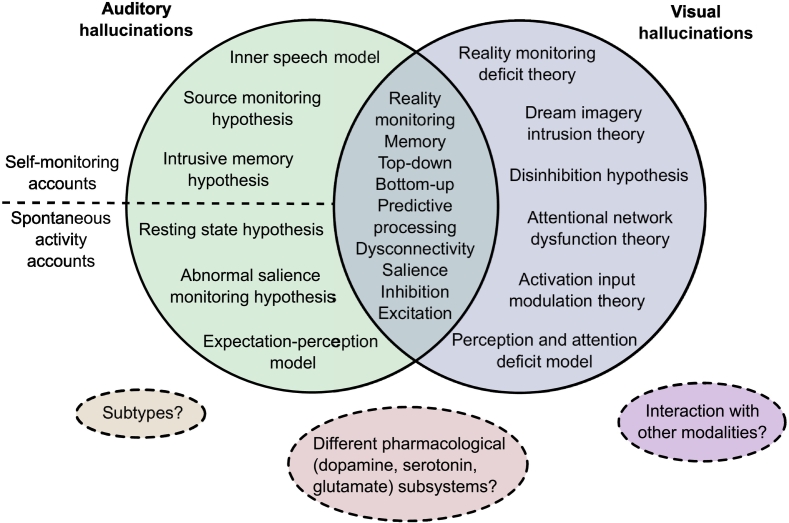

A significant issue in neuroimaging studies of hallucinations has been the lack of a clinical control group, thus confounding abnormalities specific to hallucination status with those of the broader phenotype. Equally challenging has been a tangled conceptual landscape, with numerous models proposed as cognitive or neurobiological accounts of auditory or visual hallucinations [5], [26], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41] (Fig. 1). Though an influential model of auditory hallucinations is the inner speech model [45], which proposes that AVHs arise from misattributing inner speech to a non-self source, alternative models posit the causal agent to be memory-related processes [28], spontaneous activation in auditory and related memory areas [29], inappropriate proximal salience [30], skewed balance of top-down/bottom-up control dynamics between secondary sensory cortices and frontal regions [26], [33] or of inhibition/excitation at the physiological level [34], or the mismatch between processes comparing predictive representations of the external world to sensory evidence [31], [35], [37]. While these models attempt to explain auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia and non-clinical populations, a separate array of models have been proposed for visual hallucinations in neurodegenerative disorders like PD and AD [5], [32], [36], [46]. Auditory and visual hallucination models overlap in alluding to deficits in reality monitoring, memory, salience, inhibition, and excitation. Additionally, hallucinations have been subcategorized by different neurocognitive mechanisms [40], or by differential contribution of a range of pharmacological systems [41]. Obtaining differentiating evidence is difficult as these models are not mutually exclusive, each drawing upon a similar repertoire of constituents, making it non-trivial to derive corresponding predictions [42]. However, specific morphological variation can differentiate patients who do and do not hallucinate [43], indicating that structural MRI can provide insights into why individuals hallucinate.

Fig. 1.

Landscape of theoretical models of hallucinations. The major cognitive, psychological, and neurobiological theories for auditory and visual hallucinations are depicted. Separate theories have been proposed to underlie auditory versus visual hallucinations, although they share many common themes. Different theories within each modality category are not mutually exclusive and may overlap in their predictions. Dotted lines delineate proposals of divisions between, extensions to, or limitations of current theories.

Key references: Inner speech model [45]; Intrusive memory hypothesis [28]; Resting state hypothesis [29]; Abnormal salience monitoring hypothesis [30]; Expectation-perception model [31]; Reality monitoring deficit theory, Dream imagery intrusion theory, Activation input modulation theory [36], [46]; Disinhibition hypothesis [5]; Perception and attention deficit model [32]; Top-down bottom-up models [26], [33]; Excitatory-inhibitory imbalance [34]; Predictive processing accounts [35], [37]; proposal of divide between self-monitoring accounts and spontaneous activity accounts for auditory verbal hallucinations (AVH) [38]; proposal of subtypes for AVH [40]; proposal for differential contribution of pharmacological subsystems to different types of AVH [41]; commentary on need to address interaction between and hierarchy of different modalities of hallucinations [40].

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) is a common method for unbiased, automated quantification of GM differences between groups. Conducting a meta-analysis of VBM studies is an objective approach to synthesize the extant literature and identify replicable findings [44]. Knowledge of neuroanatomical signatures of hallucinations present in certain populations and absent in others would clarify the continuum model by identifying whether there exist common neural correlates and contribute towards a clearer neurobiological picture of the origins and mechanisms of hallucinations. Considering the cultural and historical influences on hallucination interpretation [14], an organic model of hallucinations could moreover substantiate accurate diagnostic criteria. This meta-analysis and systematic review quantitatively compared people with and without hallucinations in terms of brain structure to identify the neuroanatomy related to the transdiagnostic presence of hallucinations.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A systematic review of the literature for the structural correlates of hallucinations was conducted in October 2017, with update notifications received until May 2018. Following PRISMA guidelines [47], articles were identified by searching PubMed and Web of Science using the keyword combination (hallucinat*) AND (MRI OR magnetic resonance imaging OR morphology OR voxel?based OR morphometr* OR neural correlate OR structur*) with no date limit. Reviews and meta-analyses on neuroimaging of hallucinations were cross-referenced to ensure no relevant studies were missed [20], [23], [24], [25], [26].

Studies were included in the meta-analyses if they: (a) employed structural MRI in a whole-brain investigation of voxelwise differences in GM reported in standard stereotaxic space; (b) included a direct comparison between groups with and without hallucinations within the same diagnostic category. Corresponding authors were contacted to request coordinate information if not reported in the original article, or to clarify methodological issues. CPER evaluated all studies and JS, GKM, or JRG confirmed the selection criteria, with uncertainties discussed to consensus. Region of interest (ROI) VBM studies and studies using non-voxelwise structural MRI methods that otherwise matched inclusion criterion (b) were included in the systematic review.

2.2. Data Analysis

Voxel-wise meta-analyses were undertaken using anisotropic effect-size seed-based d Mapping (AES-SDM; https://www.sdmproject.com/) [48], [49] following recommended guidelines [44] (Supplementary S1). AES-SDM uses peak coordinates and effect sizes from primary studies to create maps of meta-analytic effect size and variance of the signed GM differences. Similar to other voxel-based meta-analytic methods [50], loci from primary studies are estimated as smoothed spheres and meta-analytic maxima calculated by weighting the encompassed voxels [48]. Additionally, AES-SDM incorporates the effect sign (increases or decreases) and the t-statistic associated with each peak, increasing both sensitivity and accuracy [48]. AES-SDM also allows inclusion of non-significant studies, reducing bias towards positive results. AES-SDM is detailed elsewhere (https://www.sdmproject.com/software/tutorial.pdf), and summarized in Supplementary Methods.

Anticipating differences in mechanisms of hallucinations between psychiatric illnesses and neurodegenerative diseases based on distinctions in phenomenology, modality, prevalence [51], and the significant participant age separation among primary studies (t(25) = 17.324, p < 0.001), we performed a meta-analysis including schizophrenia, first episode schizophrenia (FES), first episode psychosis (FEP), and young adults at clinical risk for psychosis (at-risk mental state long-term, ARMS-LT), and BD, and a second of neurodegenerative disorders, including PD and AD. Of the 16 studies included in these two cross-sectional meta-analyses, three (see Table 1) did not make an explicit comparison between a hallucination (H) and no-hallucinations (NH) group, though the majority of patients in each group respectively either did or did not have hallucinations, and were therefore included [52], [53], [54]. A jackknife sensitivity analysis was performed on the meta-analyses to test reproducibility of significant brain regions by iteratively repeating the statistical analysis systematically excluding one study [55]. Finally, we formally assessed group differences between psychiatric and neurodegenerative hallucination meta-analyses using Monte Carlo randomizations to determine statistical significance [56] and performed a conjunction analysis of the simple overlap between meta-analyses to detect whether there were GM differences common to both psychiatric and neurodegenerative hallucinations [57], [58].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of included studies.

| Group | Study | Sample | N | Age (SD) | M/F | Hallucination Assessment Scale (Timescale) | Modality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric | Garrison et al., 2015 [43] | SCZ-H SCZ-NH |

79 34 |

38.5 (9.8) 40.7 (9.8) |

65/14 27/7 |

Clinical interview (lifetime history) | Mixed |

| Gaser et al., 2004 [59] | SCZ-H SCZ-NH |

29 56 |

36.2 (10.9)e | 52/33e | SAPS (variable up to weeks before/after scanning) | Auditory | |

| Shapleske et al., 2002 [60] | SCZ-H SCZ-NH |

41 31 |

35.5 (8.8) 32.0 (7.5) |

41 31 |

SAPS (course of illness) | Auditory | |

| van Swam et al., 2012c,d[52] | SCZ-H SCZ-NH |

10 10 |

40.9 (8.8) 36.3 (5.6) |

5/5 7/3 |

PANSS, semi-structured interview (course of illness) | Auditory | |

| van Tol et al., 2014 [61] | SCZ-H SCZ-NH |

31 20 |

33.4 (12.5) 35.0 (9.7) |

27/4 17/3 |

PANSS (previous week) | Auditory | |

| Huang et al., 2015 [62] | FES-H FES-NH |

18 18 |

22.6 (6.7) 22.7 (3.9) |

10/8 9/9 |

PANSS, HAHRS (previous month) | Auditory | |

| Smieskova et al., 2012b,d[53] | FEP-H ARMS-LT-NH |

16 13 |

25.1 (4.6) 24.6 (2.2) |

12/4 8/5 |

BRPS (variable) | Auditory | |

| Neves et al., 2016 [63] | BD-H BD-NH |

9 12 |

37.7 (12.1) 39.9 (15.0) |

3/6 6/6 |

MINI-Plus (lifetime history) | Auditory or visual | |

| Neurodegenerative | Goldman et al., 2014 [64] | PD-H PD-NH |

25 25 |

74.8 (6.0) 75.4 (6.1) |

17/8 18/7 |

MDS-UPDRS (at least previous month) | Mixed |

| Meppelink et al., 2011 [65] | PD-H PD-NH |

11 13 |

Not reported | Not reported | NPI (previous month) | Visual | |

| Pagonbarraga et al., 2014 [66] | PD-H PD-NH |

15 27 |

64.1 (9) 66.3 (8) |

Not reported | MDS-UPDRS (previous month) | Passage and/or presence | |

| Ramirez-Ruiz et al., 2007 [67] | PD-H PD-NH |

18 20 |

Not reported | 8/12 7/11 |

NPI Spanish version, semi-structured interview (previous year) | Visual | |

| Watanabe et al., 2013 [68] | PD-H PD-NH |

13 13 |

66.6 (5.5) 63.6 (10.7) |

7/6 5/8 |

UPDRS (not specified) | Visual | |

| Shin et al., 2012 [69] | nPD-H nPD-NH |

46 64 |

71.3 (5.9) 70.7 (5.7) |

26/38 18/9 |

NPI (not specified) | Visual | |

| Lee et al., 2016a,d[54] | AD-H AD-NH |

17 25 |

74.3 (7.3) 72.4 (9.4) |

4/13 6/19 |

NPI Korean version (at least previous month) | Auditory or visual | |

| Blanc et al., 2014 [70] | AD-H AD-NH |

39 39 |

76.0 (7.4) 76.4 (7.2) |

20/19 20/19 |

NPI (previous month) | Auditory or visual |

Abbreviations: AD: Alzheimer's disease; PD: Parkinson's disease; SCZ: schizophrenia; FES: first episode schizophrenia; BD: bipolar disorder; nPD: Parkinson's disease without dementia; FEP: first episode psychosis; ARMS-LT: at risk mental state long-term; X-H: population X with hallucinations; X-NH: population X without hallucinations; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; MDS-UPDRS: Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson's disease Rating Scale (UPDRS); PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; HAHRS: Hoffman Auditory Hallucination Rating Scale; MINI-Plus; Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Plus; SAPS: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; BRPS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale.

Lee et al. (2016) compared AD patients with misidentification subtype to AD patients without psychosis, though they classified AD patients with hallucination into the misidentification subtype.

Smieskova et al. (2012) compared FEP to ARMS-LT participants, though the groups differed significantly (p < 0.0001) in their hallucination score, with the FEP group having a mean (S.D.) score of 3.5 (2.0) on the BRPS hallucination item 10 (moderate – moderately severe) and the ARMS-LT group having a mean score of 1.4 (1.0) — a score of 1 being the lowest possible score.

Van Swam et al. (2012) used voxel-wise cortical thickness, as opposed to VBM. Though a different analysis, VWCT and VBM are considered complementary methods [97].

Studies considered proxy comparisons between hallucinating and non-hallucinating groups.

For total sample of patients with schizophrenia, including both H and NH.

2.3. Role of The Funding Source

There was no funding source for this study. CPER had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3. Results

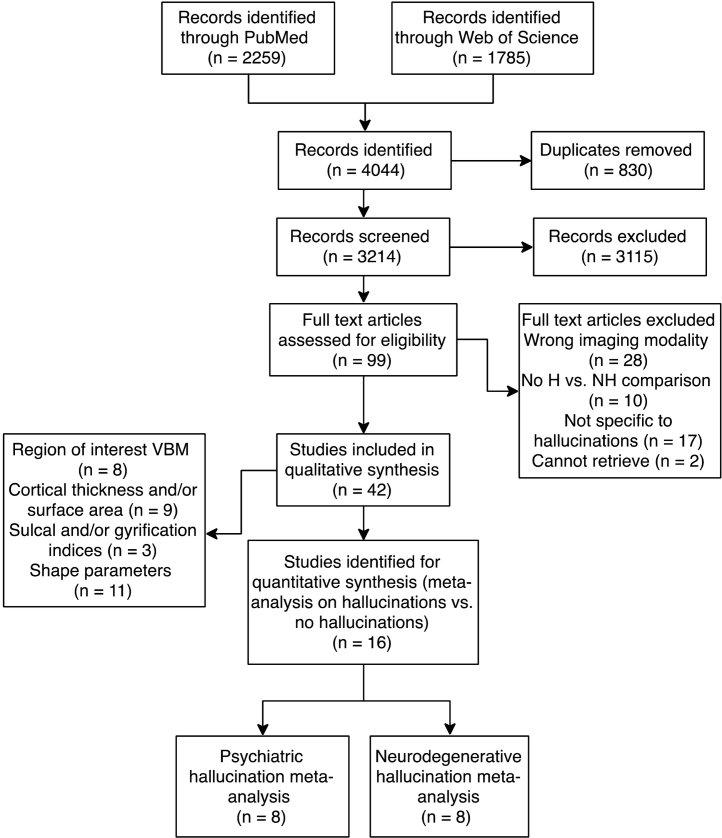

The literature search identified 2259 articles from PubMed and 1785 from Web of Science, for a merged total of 3214 after duplicates were excluded (Fig. 2). 99 articles were selected for whole text retrieval after title/abstract screening. 16 studies met criteria for the meta-analyses [43], [52], [53], [54], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71] (see Table 1 for sample characteristics; Table 2 for analysis details and results summary) and 28 papers (18 psychiatric; 10 neurodegenerative) for the systematic review of other structural metrics comparing groups with and without hallucinations.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flowchart for identification and selection of studies. Some studies performed analyses of multiple structural features and are therefore represented more than once. Abbreviations: H: population with hallucinations; NH: population without hallucination; VBM: voxel-based morphometry.

Table 2.

Imaging characteristics and key results of included studies.

| Group | Study | T | Software | Covariates | FWHM (mm) | Statistical Threshold | Original stereotaxic space | n Foci | Main result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric | Garrison et al., 2015 [43] | 1.5 | SPM8 | TIV | 8 | p < 0.001, uncorrected; minimum cluster size = 100 voxels | MNI | 2 | H > NH: bilateral occipital lobe |

| Gaser et al., 2004 [59] | 1.5 | SPM99 | SANS total score, SAPS total score without auditory hallucination sub-items, gender | 8 | p < 0.001, uncorrected, k = 100 voxels | Talairach | 4 | H < NH: L transverse temporal (Heschl's) gyrus R middle/inferior frontal gyrus, L midde temporal gyrus, L paracingulate gyrus, | |

| Shapleske et al., 2002 [60] | 1.5 | AFNI | Age, handedness | − 4.2 | Absolute value of standard error < 1.96 | Talairach | 1 | H < NH: L insular cortex | |

| van Swam et al., 2012 [52] | 3 | Brain Voyager QX 1.9 | None | Not reported | p < 0.05, cluster size > 15 voxels, corrected for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni p < 0.0063) | MNI | 7 | H > NH: L middle frontal gyrus, L posterior cingulate gyrus, L frontal insula, L parahippocampal gyrus, L postcentral sulcus, R visual cortexH < NH: posterior inferior temporal sulcus, postcentral gyrus | |

| van Tol et al., 2014 [61] | 3 | SPM8 | Age, sex | 8 | p < 0.05, FWE-corrected (cluster level), voxel-wise threshold of p < 0.005 uncorrected | MNI | 3 | H < NH: L putamen | |

| Huang et al., 2015 [62] | 3 | SPM8 | Age, gender, years of education | 8 | p < 0.001, uncorrected | Talairach | 0 | n.s. | |

| Smieskova et al., 2012 [53] | 3 | SPM8 | Age, gender, total GMV | 8 | p < 0.001, uncorrected (cluster-forming threshold); p < 0.05 FWE-corrected | MNI | 3 | H < NH: L parahippocampal gyrus H > NH: L superior frontal gyrus, L caudate |

|

| Neves et al., 2016 [63] | 1.5 | SPM8 | Total GMV | 8 | p < 0.05, whole-brain FWE-corrected | Not reported | 0 | n.s. | |

| Neurodegenerative | Goldman et al., 2014 [64] | 1.5 | SPM8 | TIV | 8 | p < 0.01, uncorrected; cluster extent threshold k = 10 | Talairach | 18 | H < NH: bilateral cuneus, bilateral fusiform gyrus, bilateral inferior parietal lobule, bilateral precentral gyrus, bilateral middle occipital gyrus, R lingual gyrus, bilateral cingulate gyrus, L paracentral lobule |

| Meppelink et al., 2011 [65] | 3 | SPM5 | Total GM | 10 | p < 0.05, brain-volume corrected cluster-level | MNI | 0 | n.s. | |

| Pagonbarraga et al., 2014 [66] | 1.5 | SPM5 | Age, gender, global GMV | 12 | p < 0.001, uncorrected; cluster size = 207 voxels (determined by 1000 Monte Carlo simulations) | MNI | 4 | H < NH: R vermis, R precuneus H > NH: posterior lobe of cerebellum, L inf. frontal cortex |

|

| Ramirez-Ruiz et al., 2007 [67] | 1.5 | SPM2 | TIV, MMSE, Hamilton score, Hoehn and Yahr score | 12 | p < 0.05, corrected cluster p-level | Talairach | 3 | H < NH: bilateral sup. parietal lobe, L lingual gyrus | |

| Watanabe et al., 2013 [68] | 3 | SPM8 | TIV, age, sex | 8 | p < 0.01, FWE corrected; cluster size > 50 voxels and z-scores ≥ 3.00 | MNI | 15 | H < NH: bilateral middle frontal gyrus, L cingulate gyrus, R inferior parietal lobule, bilateral cuneus, L fusiform gyrus, L posterior lobe, L inferior occipital gyrus, L inferior frontal gyrus, L declive, R lingual gyrus | |

| Shin et al., 2012 [69] | 3 | SPM8 | Age, sex, PD duration, intracerebral volume, K-MMSE score | 6 | p < 0.05, FWE corrected; uncorrected p < 0.001 at the voxel level, minimum cluster size = 100 voxels | Talairach | 5 | H < NH: R inferior frontal gyrus, L thalamus, L uncus, L parahippocampal gyrus | |

| Lee et al., 2016 [54] | 3 | SPM8 | Age, gender, education, TIV, CDR score, NPI non-psychotic scores | 8 | p < 0.001, uncorrected; extent threshold of contiguous 100 voxels (k > 100) | MNI | 6 | H < NH: R inferior parietal lobule, R lingual gyrus, L cuneus, R middle frontal gyrus, R superior occipital gyrus, R middle temporal gyrus | |

| Blanc et al., 2014 [70] | 1.5 | SPM12b | Age, total GMV | 8 | p < 0.001, uncorrected; minimum cluster size = 25 voxels | MNI | 3 | H < NH: R insula/inferior frontal gyrus, L superior frontal gyrus, bilateral lingual gyrus |

Abbreviations: AD: Alzheimer's disease; PD: Parkinson's disease; SCZ: schizophrenia; FES: first episode schizophrenia; BD: bipolar disorder; nPD: Parkinson's disease without dementia; FEP: first episode psychosis; ARMS-LT: at risk mental state long-term; X-H: population X with hallucinations; X-NH: population X without hallucinations; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; MDS-UPDRS: Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson's disease Rating Scale (UPDRS); PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; HAHRS: Hoffman Auditory Hallucination Rating Scale; MINI-Plus; Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Plus; SAPS: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; BRPS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; SANS: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; FWE: family-wise error; TIV: total intracranial volume; GM: gray matter; GMV: gray matter volume; CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating scale; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; K-MMSE: Korean version of MMSE; L: left; R: right.

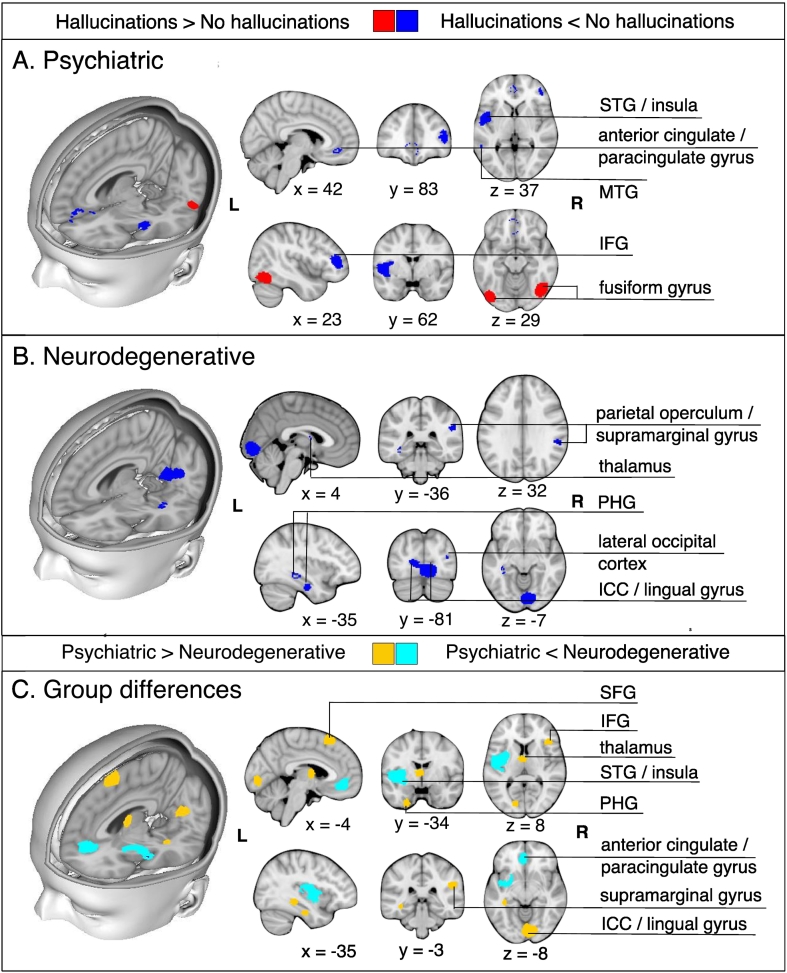

In psychiatric patients with hallucinations, relative to those without, GM reductions were identified in the left insula, right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), left anterior cingulate/paracingulate gyrus, and left middle temporal gyrus (MTG), while GM increases were observed in bilateral fusiform gyrus (Table 3, Fig. 3). Significant decreases in GM were apparent in six brain regions in patients with neurodegenerative disorders with hallucinations compared to those without: (1) left lingual gyrus; (2) right supramarginal gyrus/parietal operculum; (3) left fusiform gyrus; (4) left parahippocampal gyrus; (5) right thalamus; (6) right lateral occipital gyrus (Table 3, Fig. 3). Individuals with psychiatric relative to neurodegenerative hallucinations showed decreased GM in the left insula and anterior cingulate/paracingulate gyrus, and greater GM in the right lingual gyrus, IFG, and supramarginal gyrus, left thalamus, fusiform gyrus, inferior occipital gyrus, parahippocampal and hippocampal gyri, and bilateral SFG (Table 4, Fig. 3). There were no regions of GM alterations that were common to hallucination status between the psychiatric and neurodegenerative meta-analyses.

Table 3.

Regions of significant differences in gray matter between patients with hallucinations compared to those without for psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders.

| Group | Contrast | Region | Peak local maximum |

Jackknife sensitivity analysisa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNI coordinate | Cluster size (no. of voxels) | SDM Z-score | Uncorrected p-value | ||||

| Psychiatric | H < NH | L insula | − 46,2,− 2 | 820 | − 1.885 | 0.0000464 | 7/8 |

| R inferior frontal gyrus, pars triangularis/frontal pole | 48,36,8 | 281 | − 1.464 | 0.0008257 | 7/8 | ||

| L anterior cingulate gyrus/paracingulate gyrus | 0,36,− 2 | 132 | − 1.259 | 0.0028023 | 7/8 | ||

| L middle temporal gyrus | − 58,− 42,− 2 | 30 | − 1259 | 0.0028023 | 7/8 | ||

| H > NH | R fusiform gyrus | 44,− 64,− 18 | 574 | 1.455 | 0.0000877 | 7/8 | |

| L lateral occipital cortex/fusiform gyrus | − 40,− 82,− 16 | 345 | 1.454 | 0.0000981 | 7/8 | ||

| Neurodegenerative | H < NH | L lingual gyrus/intracalcarine cortex | 0,− 86,− 4 | 1275 | − 2.621 | 0.0000103 | 8/8 |

| L fusiform gyrus/inferior temporal gyrus | − 36,− 18,− 26 | 50 | − 1.860 | 0.0009702 | 7/8 | ||

| R supramarginal gyrus/parietal operculum | 54,− 36,30 | 75 | − 1.609 | 0.0034835 | 6/8 | ||

| L parahippocampal gyrus | − 38,− 32,− 10 | 42 | − 1.740 | 0.0018579 | 7/8 | ||

| R thalamus | 2,− 2, 12 | 14 | − 1.637 | 0.0030603 | 7/8 | ||

| R lateral occipital cortex | 36,− 80,14 | 10 | − 1.511 | 0.0043970 | 6/8 | ||

Abbreviations: H: Hallucinations; NH: No hallucinations; L: left; R: right.

The jackknife sensitivity analysis tests the reproducibility of significant brain regions by iteratively repeating the statistical analysis, but systematically excluding one study from each replication [55]. Fractions show the number of study combinations in which the region was preserved out of the total number of dataset combinations.

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis results for individuals with hallucinations compared to those without hallucinations in psychiatric (A) and in neurodegenerative disorders (B). A. For psychiatric disorders, the meta-analysis revealed gray matter decreases in the left insula, right inferior frontal gyrus (pars triangularis)/frontal pole, left anterior cingulate gyrus/paracingulate gyrus, left middle temporal gyrus, and gray matter increases in the bilateral fusiform gyrus in patients with hallucinations relative to those without. B. For neurodegenerative disorders, the meta-analysis revealed decreases in the left lingual gyrus/intracalcarine cortex, left fusiform gyrus, right supramarginal gyrus, left parahippocampal gyrus, right thalamus, and right lateral occipital cortex. C. Formal comparison between meta-analyses revealed reduced GM in the left insula and left anterior cingulate/paracingulate gyrus for individuals with psychiatric relative to neurodegenerative hallucinations, and greater GM in the right lingual gyrus, IFG, and supramarginal gyrus, left thalamus, fusiform gyrus, inferior occipital gyrus, parahippocamapal and hippocampal gyri, and bilateral SFG.

Abbreviations: STG: superior temporal gyrus; MTG: middle temporal gyrus; IFG: inferior frontal gyrus; PHG: parahippocampal gyrus; ICC: intracalcarine cortex; SFG: superior frontal gyrus.

Table 4.

Regions of significant differences in gray matter between psychiatric and neurodegenerative hallucinations.

| Contrast | Region | Peak local maximum |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNI coordinate | cluster size (no. of voxels) | SDM Z-score | uncorrected p-value | ||

| Psychiatric < neurodegenerative | L insula | − 42,− 2,2 | 1784 | 1.794 | < 0.0001 |

| L anterior cingulate gyrus/paracingulate gyrus | 0,44,− 10 | 372 | 1.235 | 0.0011147 | |

| Neurogenerative < psychiatric | R lingual gyrus | 4,− 84,− 6 | 1080 | − 2.331 | 0.0000206 |

| L superior frontal gyrus | − 10,26,64 | 167 | − 1.403 | 0.0016670 | |

| R supramarginal gyrus | 52,− 34,28 | 131 | − 1.365 | 0.0020230 | |

| L thalamus | − 4,− 4,10 | 115 | − 1.516 | 0.0008154 | |

| L fusiform gyrus | − 24,− 2,− 42 | 90 | − 1.494 | 0.0010064 | |

| R inferior frontal gyrus, pars triangularis | 42,24,8 | 82 | − 1.444 | 0.0013469 | |

| L inferior occipital gyrus | − 44,− 78,− 16 | 71 | − 1.482 | 0.0010786 | |

| L parahippocampal gyrus | − 32,− 18,− 26 | 51 | − 1.450 | 0.0013160 | |

| R superior frontal gyrus | 14,36,− 30 | 34 | − 1.515 | 0.0008464 | |

| L hippocampus | − 36,− 34,− 8 | 33 | − 1.524 | 0.0007690 | |

28 studies employed a regional and/or non-voxelwise approach to evaluate structural MRI data with respect to hallucination status: seven studies performed VBM restricted to predefined ROIs [43], [63], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], one performed source-based morphometry [76], nine explored cortical thickness (CT) and/or surface area [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], three investigated gyral/sulcal properties [43], [86], [87], and 11 assessed structure-specific shape parameters [43], [83], [85], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95]. Results are summarized in Table 5, Table 6. Overall, findings were heterogeneous, with few direct replications. In schizophrenia, the most consistent findings were reductions in CT in the vicinity of the left or right temporal gyrus for patients with hallucinations compared to those without [77], [78], [96], coincident with the reductions in GM in left MTG observed in the meta-analysis (Fig. 3). However, two studies reported increases in GM in temporal regions with hallucinations [90], [92]. Hallucinations in PD and DLB were characterized by distributed patterns of cortical thinning [83], [84] and related to hippocampal volume, though the direction of this association was mixed [83], [85].

Table 5.

Summary of systematic review from GMV ROI studies of regional brain volume comparing individuals with and without hallucinations.

| Group | Study | Sample (M/F) | Age (SD) | Hallucination modality (assessment scale) | ROI(s) | Analysis (imaging software) | Main result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric | Garrison et al., 2015 [43] | 79 (65/14) SCZ-H 34 (27/7) SCZ-NH |

38.5 (9.8) 40.7 (9.8) |

Mixed (clinical interview) | Medial profrontal cortex (mPFC) | VBM (SPM12) | Gray matter volume SCZ-H > SCZ-NH: mPFC region surrounding the anterior PCS |

| Cierpka et al., 2017 [71] | 10 (6/4) SCZ-H 10 (8/2) SCZ-NH |

36.5 (9.0) 32.1 (6.2) |

Auditory (BRPS, PANSS, PsyRatS) | Cerebellum | VBM (SPM8) | Gray matter volume SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: right lobule VIIIa |

|

| Kubera et al., 2014 [76] | 10 (6/4) SCZ-H 10 (8/2) SCZ-NH |

36.5 (9.0) 32.1 (6.2) |

Auditory (BRPS, PANSS, PsyRatS) | n/a | SBM (GIFT) | Gray matter volume SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: component consisting MFG; IFG; STG; insula; IPL; rectal gyrus; transverse temporal gyrus; supramarginal gyrus; lingual gyrus; postcentral gyrus; fusiform gyrus; subcallosal gyrus; MTG; ITG; orbital gyrus |

|

| Neves et al., 2016 [63] | 9 (3/6) BD-H 12 (6/6) BD-NH |

37.7 (12.1) 39.9 (15.0) |

Auditory or visual (MINI-Plus) | Orbitofrontal cortex and ventral prefrontal areas, cingulate gyrus, fusiform gyrus, superior temporal sulcus, amygdala, insula, thalamus | VBM (SPM8) | Gray matter volume BD-H < BD-NH: right posterior insular cortex |

|

| Stanfield et al., 2009 [72] | 17 (n/a) BD-H 49 (n/a) BD-NH |

36.4 (11.1)a | Auditory (OPCRIT symptom checklist) | Temporal lobe | VBM (SPM99) | Gray matter density BD-H < BD-NH: left middle temporal gyrus |

|

| Neurodegenerative | Janzen et al., 2012 [73] | 13 (6/7) PD-H 13 (7/6) PDD-H 16 (9/7) PD-NH |

66.0 (6.9) 67.7 (7.1) 64.3 (8.0) |

Visual (UPDRS) | Pedunculopontine nucleus (PPN), thalamus | VBM (SPM8) | Gray matter volume PD-H + PDD-H < PD-NH: PPN, thalamus PD-H < PD-NH: PPN |

| Sanchez-Castenada et al., 2010 [74] | 6 (4/2) DLB-H 6 (4/2) DLB-NH 8 (6/2) PDD-H 7 (4/3) PDD-NH |

70.2 (12.4) 71 (10.7) 75.3 (4.9) 70.6 (7.1) |

Visual (NPI) | Frontal (BA 6, 8, 9, 10, 44, 45, and 47), occipital (BA 18,19), parietal (BA 7, 39, 40), and temporal (20) regions | VBM (SPM5) | Gray matter volume DLB-H < DLB-NH: right inferior frontal gyrus (BA 45) PDD-H < PDD-NH: left orbitofrontal lobe (BA 10) |

|

| Colloby et al., 2017 [75] | 41 (26/15) DLB-H 47 (33/14) AD-NH |

78.6 (6.2) 79.0 (8.8) |

Visual (NPI) | Substantia innomiata (SI) | VBM (SPM8) | Gray matter volume n.s. |

Abbreviations: AD: Alzheimer's disease; PD: Parkinson's disease; PDD: Parkinson's disease with dementia; SCZ: schizophrenia; FES: first episode schizophrenia; BD: bipolar disorder; nPD: Parkinson's disease without dementia; FEP: first episode psychosis; ARMS-LT: at risk mental state long-term; DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies; X-H: population X with hallucinations; X-NH: population X without hallucinations; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; MDS-UPDRS: Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson's disease Rating Scale (UPDRS); PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; HAHRS: Hoffman Auditory Hallucination Rating Scale; MINI-Plus; Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Plus; SAPS: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; BRPS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; OPCRIT: Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness and Affective Illness; MFG: medial frontal gyrus; IFG: inferior frontal gyrus; STG: superior temporal gyrus: IPL: inferior parietal lobule; MTG: middle temporal gyrus; ITG: inferior temporal gyrus; SBM: source-based morphometry.

Hallucination and no-hallucinations groups combined.

Table 6.

Summary of systematic review from non-voxelwise structural studies comparing individuals with and without hallucinations.

| Measure | Group | Study | Sample (M/F) | Age (SD) | Hallucination modality (Assessment Scale) | Analysis (Imaging software) | Main result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical thickness and/or cortical surface area | Psychiatric | Chen et al., 2015 [77] | 18 (12/6) FES-H 31 (17/14) FES-NH |

24.1 (6.3) 24.3 (5.9) |

Auditory (AHRS, SAPS/SANS) | Whole-brain vertex-wise cortical thickness (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness FES-H < FES-NH: right Heschl's gyrus (HG) Negative correlation with hallucination severity by AHRS, but not SAPS/SANS scoring: Right HG |

| Cui et al., 2017 [78] | 115 (52/63) SCZ-H 93 (47/36) SCZ-NH |

26.4 (5.7) 27.3 (5.1) |

Auditory (PANSS, AHRS) | Whole brain vertex-wise cortical thickness (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: left middle temporal gyrus (MTG) Negative correlation with hallucination severity by PANSS P3, but not AHRS scoring across all SCZ patients: left MTG |

||

| Morch-Johnsen et al., 2017 [79] | 145 (82/63) SCZ-H 49 (33/16) SCZ-NH |

31.1 (9.3) 30.9 (8.4) |

Auditory (PANSS) | ROI cortical thickness and surface area analysis of bilateral Heschl's gyrus (HG), planum temproale (PT) and superior temporal gyrus (STG) (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: left HG Cortical surface area n.s. |

||

| Morch-Johnsen et al., 2018 [80] | 49 (18/31) BD-H 108 (48/60) BD-NH |

33.4 (12.0) 35.0 (11.4) |

Auditory (SCID) | Whole-brain vertex-wise and ROI cortical thickness (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness BD-H > BD-NH: left HG (ROI) and superior parietal lobule (whole-brain) Cortical surface area n.s. |

||

| Yun et al., 2016 [81] | 27 (9/18) FEP-H 24 (12/12) FEP-NH |

22.5 (5.0) 22.7 (5.1) |

Auditory (PANSS) | Support vector machine using cortical surface area and cortical thickness measures | Optimal feature sets of individualized cortical structural covariance (ISC) FEP-H vs. FEP-NH (83.6% accuracy): 3 CSA-ISCs incl. The intraparietal sulcus, Broca's complex, and the anterior insula FEP-H vs. FEP-NH (82.3% accuracy): 6 CT-ISCs incl. Executive control network and Wernicke's module |

||

| van Lutterveld et al., 2014 [82] | 50 (19/31) NC-H 50 (19/31) NC-NH |

40.8 (11.6) 40.5 (15.0) |

Auditory (modified LSHS) | Whole-brain vertex-wise cortical thickness (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness NC-H < NC-NH: left paracentral cortex, left pars orbitalis, right fusiform gyrus, right ITG, right insula |

||

| Neurodegenerative | Ffytche et al., 2017 [83] | 21 (15/6) PD-H 286 (192/94) PD-NH |

64.43 (7.5) 61.97 (9.9) |

Visual (UPDRS) | Whole-brain vertex-wise cortical thickness (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness PD-H < PD-NH: right supramarginal gyrus, superior frontal cortex, lateral occipital cortex |

|

| Delli Pizzi et al., 2014 [84] | 18 (9/9) DLB-H 15 (7/8) AD-NH |

75.5 (4.0) 75.6 (7.6) |

Visual (NPI) | Whole brain vertex-wise cortical thickness (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness DLB-H < AD-NH: right posterior regions (superior parietal gyrus, precuneus, cuneus, pericalcarine and lingual gyri) Negative correlation with hallucination severity by NPI hallucination item scoring in DLB patients: right precuneus and superior parietal gyrus |

||

| Delli Pizzi et al., 2016 [85] | 19 (9/10) DLB-H 15 (6/9) AD-NH |

76.4 (4.4) 76.5 (7.2) |

Visual (NPI) | Between group differences in cortical thickness of entorhinal, parahippocampal, and perirhinal structures (Freesurfer) | Cortical thickness n.s. |

||

| Sulci and gyrification measures | Psychiatric | Garrison et al., 2015 [43] | 79 (65/14) SCZ-H 34 (27/7) SCZ-NH |

38.5 (9.8) 40.7 (9.8) |

Mixed (clinical interview) | ROI LGI of mPFC regions of interest (frontopolar, medial orbitofrontal, superior frontal and paracentral cortices) (Freesurfer) | Local gyrification index SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: mPFC regions surrounding PCS (bilateral frontopolar, medial orbitofrontal, superior frontal and paracentral cortices) |

| Kubera et al., 2018 [86] | 10 (6/4) SCZ-H 10 (8/2) SCZ-NH |

36.5 (9.0) 32.1 (6.2) |

Auditory (BRPS, PANSS, PsyRatS) | Whole-brain vertex-wise local gyrification index (Freesurfer) | Local gyrification index SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: left Broca's area, right Broca's homolog, right superior middle frontal cortex SCZ-H > SCZ-NH: precuneus and superior parietal cortex Negative correlation between LGI and hallucination severity by BPRS total score: left Broca's area and its right homolog, precuneus, superior parietal cortex |

||

| Cachia et al., 2015 [87] | 16 (9/7) SCZ-VH 17 (11/6) SCZ-NVH |

30.4 (12.6) 30.5 (8.7) |

Visual (PANSS, SAPS) | Between group differences in global sulcal indices (BrainVisa) | Global sulcation index SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: right parietal cortex and left sylvian fissure |

||

| Shape parameters (volume, length, surface area, intensity) | Psychiatric | Rossell et al., 2001 [88] | 42 (all M) SCZ-H 29 (all M) SCZ-NH |

35.5 (9.0) 32.3 (7.4) |

Auditory (SAPS) | Between group differences in corpus callosum (divided into 4 sections: anterior, mid-anterior, mid-posterior, posterior) surface area and length | Corpus calllosum surface area and length n.s. |

| Shapleske et al., 2001 [89] | 44 (all M) SCZ-H 30 (all M) SCZ-NH |

35.5 (8.8) 32.0 (7.5) |

Auditory (SAPS) | Between group differences in Sylvian fissure length, planum temporale surface area and volume | Sylvian fissure length, planum temporale volume and surface area n.s. |

||

| Hubl et al., 2010 [90] | 13 (8/5) SCZ-H 13 (8/5) SCZ-NH |

33 (8) 31 (9) |

Auditory (PANSS) | Between group differences in GMV of Heschl's gyrus (HG) | Gray matter volume SCZ-H > SCZ-NH: right HG |

||

| Garrison et al., 2015 [43] | 79 (65/14) SCZ-H 34 (27/7) SCZ-NH |

38.5 (9.8) 40.7 (9.8) |

Mixed (clinical interview) | Between group differences in length of paracingulate sulcus (PCS) | Length of paracingulate sulcus SCZ-H < SCZ-NH: left PCS |

||

| Amad et al., 2014 [91] | 16 (9/7) SCZ-A + VH 17 (11/6) SCZ-AH |

30.4 (12.6) 30.5 (8.7) |

visual (SAPS) | Between group differences in hippocampal volume | Mean hippocampal volume SCZ-A + VH > SCZ-AH Local hippocampal shape differences SCZ-A + VH > SCZ-AH: anterior and posterior end of CA1, subiculum |

||

| Shin et al., 2005 [92] | 17 (7/10) FEP-H 8 (2/6) FEP-NH |

31.0 (5.0) 28.4 (4.8) |

Auditory (PANSS) | Between group differences in GM and WM volumes of frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, cerebellum | Gray matter volume FEP-H > FEP-NH: frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes, ventricles White matter volume FEP-H > FEP-NH: temporal lobe |

||

| Neurodegenerative | Ffytche et al., 2017 [83] | 21 (15/6) PD-H 286 (192/94) PD-NH |

64.43 (7.5) 61.97 (9.9) |

Visual (UPDRS) | Between group differences in subcortical GMV (Freesurfer) | Subcortical gray matter volume PD-H < PD-NH: bilateral hippocampus, caudate, putamen |

|

| Pereira et al., 2013 [93] | 18 (6/12) PD-H 18 (6/12) PD-NH |

73.7 (5.4) 73.8 (6.8) |

Visual (NPI) | Between group differences in hippocampal subfield volumes (fimbria, presubiculum, subiculum, CA1, CA2–3, CA4-DG fields, hippocampal fissure) | Hippocampal subfield volumes n.s. |

||

| Yao et al., 2016 [94] | 12 (10/2) PD-H 15 (10/5) PD-NH |

70a 66a |

Visual (UPDRS) | Between group differences in hippocampal volume and vertex-wise analysis of hippocampal shape | Hippocampal volume and shape n.s. |

||

| Delli Pizzi et al., 2016 [85] | 19 (9/10) DLB-H 15 (6/9) AD-NH |

76.4 (4.4) 76.5 (7.2) |

Visual (NPI) | Between group differences in volumes of total hippocampi and hippocampal subfields (Freesurfer) | Gray matter volume AD-NH < DLB-H: left total hippocampal volume, bilateral CA1, left CA2–3, CA4-DG and subiculum |

||

| Lin et al., 2006 [95] | 5 (3/2) AD-H 5 (3/2) AD-NH |

73 (6) 73 (4) |

Visual (report from patient or caregiver) | Between group differences in white matter signal hyperintensities | Periventricular hyperintesity AD-H > AD-NH: occipital caps |

Abbreviations: AD: Alzheimer's disease; PD: Parkinson's disease; PDD: Parkinson's disease with dementia; SCZ: schizophrenia; FES: first episode schizophrenia; BD: bipolar disorder; nPD: Parkinson's disease without dementia; FEP: first episode psychosis; ARMS-LT: at risk mental state long-term; DLB: dementia with Lewy bodies; X-H: population X with hallucinations; X-NH: population X without hallucinations; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire; MDS-UPDRS: Movement Disorder Society (MDS)-sponsored version of the Unified Parkinson's disease Rating Scale (UPDRS); PANSS: Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; HAHRS: Hoffman Auditory Hallucination Rating Scale; MINI-Plus; Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Plus; SAPS: Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; BRPS: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; OPCRIT: Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness and Affective Illness; MFG: medial frontal gyrus; IFG: inferior frontal gyrus; STG: superior temporal gyrus: IPL: inferior parietal lobule; MTG: middle temporal gyrus; ITG: inferior temporal gyrus; SBM: source-based morphometry. LSHS: Launay and Slade Hallucination Scale (LSHS).

Median age.

4. Discussion

Distinctive patterns of neuroanatomical alteration characterize hallucination status in patients with psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases, with the former associated with fronto-temporal deficits and the latter with medial temporal, thalamic and occipital deficits. These results broadly align with prior meta-analyses investigating GM correlates of hallucination severity of AVH in schizophrenia, which found negative correlations between hallucination severity in schizophrenia and GMV within the bilateral STG, bilateral HG, and bilateral insula [23], [24], [26] (Supplementary S3–4) and qualitative reviews on structural imaging studies of visual hallucinations (VH) in neurodegenerative illnesses, which found GM atrophy associated with VH in patients with PD in parietal, hippocampal, and occipito-temporal regions, primarily the lingual and fusiform gyri [25], [98]. The distributed pattern of structural changes seen in both hallucination signatures is suggestive of impairment in the coordination of information flow. Indeed, AVH in schizophrenia has been associated with increased functional activation in the STG, insula, anterior cingulate, and pre/post central gyrus [21], [22], reduced resting connectivity between default mode regions [99], disruptions to the salience network [30], and altered interactions between resting-state networks [99]. Compared to AVH, VH in schizophrenia have been associated with increased seed-based functional connectivity between the amygdala and visual cortex [100], among the hippocampus, mPFC, and caudate nuclei and white matter connectivity between the hippocampus and visual areas [91], as well as decreased global sulcation in the right hemisphere [87]. VH in PD have been associated with increased functional activity in the lingual gyrus, cuneus, and fusiform gyrus [27], and hyperconnectivity in the default mode network [101]. Cortical thickness studies lend further support for divergent structural patterns, showing localized decreases in CT in temporal regions in schizophrenia spectrum disorders and more widespread decreases in dementia and PD (Table 6).

We reviewed the brain structural abnormalities associated with hallucinations, yet how changes to the brain's topological substrate translate to changes in an individual's experiential landscape remain unknown. Our findings are consistent with multiple models of hallucinations (Fig. 1). For instance, volume loss in temporal regions could reflect the misattribution of inner speech to a non-self source (inner speech model) [45], or relate to abnormalities in cortical feedback for predictive signal processing (predictive processing account) [102], or could be the result (or cause) of heightened resting state activity in the auditory cortex (resting state hypothesis) [29], or a combination of some or all of these mechanisms. That substantial heterogeneity was observed in ROI VBM hypothesis-driven studies further emphasizes the limits of current theories.

Our meta-analyses suggest that there are at least two broad biological categories of hallucination mechanism: a psychiatric mechanism and a neurodegenerative mechanism. In support, structural signatures of hallucinations in the psychiatric meta-analysis overlap with comparisons of patients to non-disordered controls. For instance, a meta-analysis of GM changes in patients with psychosis compared to healthy controls shows reductions in bilateral insula and anterior cingulate cortex [103], coinciding with regions identified in the meta-analysis of hallucinations in neurodevelopmental disorders, while thalamic, hippocampal, and occipital GM reductions in PD [104] partly coincide with the changes seen in neurodegenerative hallucinations. The relation between disorder-specific GM changes and hallucination category suggests that hallucinations share networks of brain regions with the pathologies of the disorder in which they are embedded.

Knowledge of the structural correlates of hallucination types may help understand their cognitive phenotypes. For instance, hallucinations are linked to reality monitoring, the cognitive capacity to distinguish between self-generated and external sources of information [105]. Impaired in schizophrenia, reality monitoring is associated with the structure and function of the anterior cingulate cortex [43], [105]. The cingulate gyrus is part of a network involving the IFG, ventral striatum, auditory cortex, right posterior temporal lobe whose functional connectivity is related to the subjective extent to which a hallucination feels real [106]. Indeed, we propose that connectivity is key: together with the insula, the anterior cingulate constitutes nodes of the salience network, dysfunctions in which have been proposed as central to experiencing hallucinations [30]. Structural deficits in the insula in psychosis might also underpin atypical interactions between the DMN and salience network observed in hallucinations [39]. The left STG/MTG have been robustly implicated in the manifestation of AVH [23], [102], emphasizing the importance of speech perception and processing in hallucinations in schizophrenia spectrum psychosis.

If hallucinations experienced by those with schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar psychosis are an example of a broader mechanism, then we predict that other neurodevelopmental disorders will have similar patterns of associated GM loss. For example, hallucinations have a prevalence of 43% in personality disorder [107], suggested to be a neurodevelopmental disorder [108], and are predicted to have a mechanism similar to other psychiatric disorders.

Abnormalities in the occipital cortex in neurodegenerative diseases suggest that deficits in sensory regions contribute to hallucinations of the associated sensory modality since VH are more common in PD than in schizophrenia [19]. Hallucinations in PD and AD were characterized by GM reduction in the thalamus and PHG. The thalamus mediates information in the cortical hierarchies via corticothalamo-cortico circuits and contributes to working memory maintenance [109], while the PHG is implicated in processing contextual associations in the service of memory formation and generating expectations about spatial relations [110]. Their involvement supports memory-related processes in hallucinations, though may equally relate to neurodegenerative pathologies. The anterior cingulate was implicated in hallucinations occurring in psychiatric disorders, but not neurodegenerative etiology. As the anterior cingulate is involved in self-referential processing, this is consistent with the observation that psychotic hallucinations address the individual and vary across continental location and historical time period [14], [111]. Conversely, hallucinations in PD have a more passive quality and form historically stable categories of visual percepts [4].

Anatomic heterogeneity related to hallucination presence/absence has important consequences for the plurality of treatment options. A specific example is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) used to reduce hallucination frequency and severity in schizophrenia, albeit with some reservations [112], [113]. A number of parameters including frequency of stimulation and anatomical site contribute to the outcome of rTMS, and so anatomical heterogeneity is a possible source for the ambiguity of efficacy in therapeutic trials [114]. Antipsychotic (dopamine receptor anatagonist) medication is the mainstay of treatment for hallucinations in schizophrenia, and is sometimes required in PD, with evidence of therapeutic effect in each [115], [116]. Psychological treatments include cognitive behavioral therapy and avatar therapy. However, little is known to help guide a choice of which treatment will be tolerable and effective for a given individual; efforts to develop personalized treatment for hallucinations requires an understanding of the underlying mechanism that we suggest varies across diagnosis.

The multimodality of hallucinations is under-documented and under-researched, with < 2% of studies included in this review probing hallucinations beyond audition or vision [66]. However, 30–50% of schizophrenia or PD patients report hallucinations in more than one modality [2], [117]: olfactory hallucinations are present in 10–13.7% [51], [118] and tactile sensations frequently co-occur with auditory hallucinations [1]. Despite the dimensionality of hallucinations, many questionnaires and theoretical models target unimodal accounts. Non-clinical individuals who hallucinate or hear voices are receiving increasing interest in scientific research [7], yet only one study in this review assessed a structural correlate (cortical thickness) of hallucinations in this population [82]. Similarly, no studies investigated brain structure or function of hallucinations in borderline personality disorder, in spite of a high point prevalence of 43% [107]. Although hallucinations are recognized to occur across diagnostic boundaries, the current scope of transdiagnostic research on hallucinations remains narrow.

The prevalence of auditory hallucinations in the general population varies across the lifespan with peaks in early life (< 30 years) and between 50 and 59 years [119]. Results from these meta-analyses predict that early onset of hallucinations will have a pattern of frontotemporal structural deficits similar to psychiatric disorders with neurodevelopmental origins, whilst later onset will show a neurodegenerative pattern of GM change in the occipital cortex, medial temporal lobe and thalamus. In any case, empirical neuroimaging and cognitive research in non-clinical groups and non-dominant modalities is necessary to extend the limits of current knowledge.

As with all meta-analyses, statistical power is restricted by the size of the extant literature, both in terms of the number of studies meeting inclusion criteria and sample sizes of original studies, which in neuroimaging the experience of hallucinations remains immature. Despite this, the overall sample size was comparable to other SDM meta-analyses (n = 233 H, n = 194 NH for psychiatric; n = 128 H, n = 162 NH for neurodegenerative) [120], [121]. Neuroimaging meta-analyses are often subject to heterogeneity in methodology. We noted broadly uniform software parameters and spatial smoothing, but variation in covariates and statistical thresholds (Table 2). However, all meta-analyses employed the same threshold throughout the brain, limiting bias towards any a-priori regions of interest and improving reliability of results. The questionnaires used to assess hallucination status varied in the time frame bounding the hallucination, from within the current week to lifetime history, and none conducted follow-up assessments for whether patients later developed hallucinations. Critically, few instruments evaluating hallucination presence distinguish between auditory and visual hallucinations or whether hallucinations occur at all in other modalities, such as tactile or olfactory. Even fewer assess specific phenomenological characteristics of hallucinations, which is potentially confounding as experiential differences may map to different neural substrates [122]. Understanding the neurobiology supporting the content of hallucinations may help in personalizing treatment strategies since hallucination content is related to cognitive profile in PD [116]. We recommend a more granular evaluation of hallucination modality, phenomenological properties, and lifetime and current history, including possible remission of hallucinations from antipsychotic medication or rTMS. The psychiatric and neurodegenerative meta-analyses illustrate cross-sectional neuroanatomical differences between patients with and without hallucinations. However, the prevalence of hallucinations increases with the duration of illness for PD [116], but generally decrease over time for schizoaffective disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression [8], whilst the content may equally change over the trajectory of the disorder [116]. Future analyses of longitudinal neuroimaging data may clarify illness category separation in the temporal evolution of hallucinations. The divergence in our meta-analytic findings for psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders may be partly attributable to differences in modality, since hallucinations experienced in schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar psychosis were predominantly auditory, while those in PD and AD were mostly visual. However, there was no overlap in brain regions identified in the two meta-analyses. Moreover, the reported modalities are partly construed by the questionnaire used, which often assume a unimodal account or neglect to ask about multimodal experiences or differentiate between hallucination modalities. A quantitative and qualitative comparison of the phenomenological properties of hallucinations in schizophrenia and PD found that 55% of patients with schizophrenia had VH and 45% of patients with PD had AH, emphasizing that sensory modality is not a mutually exclusive class [51]. Moreover, hallucinations involving more than one modality were reported in approximately 80% of patients for schizophrenia and PD alike. Differences in hallucinations between disorders emerge in the frequency, duration, capacity of control, negative valence, and impact of hallucinations on patients, such that people with schizophrenia were more heavily affected by their hallucinations [51]. It is therefore unlikely that differences between the psychiatric and neurodegenerative hallucination meta-analyses are due to modality alone, but capture a more complex picture of illness pathology, hallucination properties like content and affect, and mechanisms of onset or occurrence. Nonetheless, important outstanding questions are (1) whether hallucinations of the same modality have a common neural basis regardless of diagnosis, (2) why hallucination sensory modality prevalence rates differ between disorders, with AH being the most prevalent sensory modality in schizophrenia and VH for PD, and (3) how sensory modalities interact during hallucination experiences, both in terms of their serial or simultaneous presentation in time and the underlying neural systems [123]. Finally, there was also a significant difference in the ages of the participants in the two meta-analyses, although each meta-analysis had its own age-matched control group and thus the comparison between disorders did not capture differences due to aging.

Hallucinations in clinical and non-clinical populations are diverse in content, modality, frequency, and affect, among other dimensions. Though hallucinations have been explored transdiagnostically at the level of phenomenology, little empirical work has made group comparisons of brain structure related to hallucinations. We show that hallucinations in psychiatric disorders have distinct neuroanatomical organization from the pattern observed in neurodegenerative diseases, and in doing so hypothesize at least two structural substrates associated with the hallucinatory experience. This categorical differentiation in the neurobiology of hallucinations is important for optimizing or developing treatment strategies, and makes specific predictions about other disorders, such as personality disorder, and the onset of hallucinations in the general population. The structural networks involved in hallucinations partly coincide with the respective case–control comparisons, and are thus embedded within the broader neuroanatomical phenotype, emphasizing the importance of non-hallucinating patient control groups and age-matched healthy controls. Hallucinations are experienced in a variety of mental health contexts and are important phenomena in probing our perception of the external world, but theoretical work has not yet captured the diversity of hallucinations across modalities or diagnoses. By hypothesizing at least two mechanisms for hallucinations, we suggest incorporating this plurality in future research. These meta-analyses offer a critical starting point.

Contributors

JS conceived and directed the project. CPER planned the search criteria, completed the literature search, data extraction, quality assessment, data analyses and summary, created the figures, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with input from JRG, JS, and GKM. JRG, JS, and GKM confirmed the results of data extraction. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed to its writing and revision.

Declaration of Interests

Ms. Rollins reports a scholarship from Gates Cambridge during the conduct of the study. Professor Rowe reports grants from Wellcome Trust during the conduct of the study, grants from NIHR, McDonnell Foundation, PSP Association, Parkinsons UK, Medical Research Council, Evelyn Trust, and AZ-Medimmune, personal fees from Asceneuron, and other from Guarantors of Brain outside the submitted work. Professor Suckling, Dr. Murray, Dr. Garrison, Dr. Simons, and Dr. O'Callaghan have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by the following funding sources: Gates Cambridge (CPER); Wellcome Trust (JBR, 103838; CO, 200181/Z/15/Z); National Health and Medical Research Council Neil Hamilton Fairley Fellowship (CO, 1091310); Wellcome Trust Collaborative award (JRG), and a joint award from the Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (JSS).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.01.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Woods A., Jones N., Alderson-Day B., Callard F., Fernyhough C. Experiences of hearing voices: analysis of a novel phenomenological survey. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(4):323–331. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim A., Hoek H.W., Deen M.L., Blom J.D., Investigators G. Prevalence and classification of hallucinations in multiple sensory modalities in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):493–499. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baethge C., Baldessarini R.J., Freudenthal K., Streeruwitz A., Bauer M., Bschor T. Hallucinations in bipolar disorder: characteristics and comparison to unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(2):136–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diederich N.J., Fenelon G., Stebbins G., Goetz C.G. Hallucinations in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(6):331–342. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onofrj M., Taylor J.P., Monaco D. Visual hallucinations in PD and Lewy body dementias: old and new hypotheses. Behav Neurol. 2013;27(4):479–493. doi: 10.3233/BEN-129022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Q.F., Tan L., Wang H.F. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maijer K., Begemann M.J.H., Palmen S., Leucht S., Sommer I.E.C. Auditory hallucinations across the lifespan: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2018;48(6):879–888. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717002367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goghari V.M., Harrow M. Twenty year multi-follow-up of different types of hallucinations in schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, and depression. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2–3):371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakamori T., Agari T., Yasuhara T. Cognitive functions in Parkinson's disease: relation to disease severity and hallucination. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20(4):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson R.S., Krueger K.R., Kamenetsky J.M. Hallucinations and mortality in Alzheimer disease. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(11):984–990. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.11.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kjelby E., Sinkeviciute I., Gjestad R. Suicidality in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: the relationship to hallucinations and persecutory delusions. European psychiatry. 2015;30(7):830–836. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jardri R., Bartels-Velthuis A.A., Debbane M. From phenomenology to neurophysiological understanding of hallucinations in children and adolescents. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl. 4):S221–S232. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baumeister D., Sedgwick O., Howes O., Peters E. Auditory verbal hallucinations and continuum models of psychosis: a systematic review of the healthy voice-hearer literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:125–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laroi F., Luhrmann T.M., Bell V. Culture and hallucinations: overview and future directions. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl. 4):S213–S220. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waters F., Fernyhough C. Hallucinations: a systematic review of points of similarity and difference across diagnostic classes. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(1):32–43. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daalman K., van Zandvoort M., Bootsman F., Boks M., Kahn R., Sommer I. Auditory verbal hallucinations and cognitive functioning in healthy individuals. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(2–3):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Os J., Reininghaus U. Psychosis as a transdiagnostic and extended phenotype in the general population. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):118–124. doi: 10.1002/wps.20310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohlken M.M., Hugdahl K., Sommer I.E. Auditory verbal hallucinations: neuroimaging and treatment. Psychol Med. 2017;47(2):199–208. doi: 10.1017/S003329171600115X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waters F., Collerton D., Ffytche D.H. Visual hallucinations in the psychosis spectrum and comparative information from neurodegenerative disorders and eye disease. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl. 4):S233–S245. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carter R., Ffytche D.H. On visual hallucinations and cortical networks: a trans-diagnostic review. J Neurol. 2015;262(7):1780–1790. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7687-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jardri R., Pouchet A., Pins D., Thomas P. Cortical activations during auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: a coordinate-based meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(1):73–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhn S., Gallinat J. Quantitative meta-analysis on state and trait aspects of auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):779–786. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modinos G., Costafreda S.G., van Tol M.J., McGuire P.K., Aleman A., Allen P. Neuroanatomy of auditory verbal hallucinations in schizophrenia: a quantitative meta-analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Cortex. 2013;49(4):1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palaniyappan L., Balain V., Radua J., Liddle P.F. Structural correlates of auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1–3):169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pezzoli S., Cagnin A., Bandmann O., Structural Venneri A. Functional neuroimaging of visual hallucinations in Lewy body disease: a systematic literature review. Brain Sci. 2017;7(7) doi: 10.3390/brainsci7070084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen P., Laroi F., McGuire P.K., Aleman A. The hallucinating brain: a review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies of hallucinations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(1):175–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zmigrod L., Garrison J.R., Carr J., Simons J.S. The neural mechanisms of hallucinations: a quantitative meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;69:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waters F.A., Badcock J.C., Michie P.T., Maybery M.T. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: intrusive thoughts and forgotten memories. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2006;11(1):65–83. doi: 10.1080/13546800444000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Northoff G., Qin P. How can the brain's resting state activity generate hallucinations? A 'resting state hypothesis' of auditory verbal hallucinations. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):202–214. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palaniyappan L., Liddle P.F. Does the salience network play a cardinal role in psychosis? An emerging hypothesis of insular dysfunction. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2012;37(1):17–27. doi: 10.1503/jpn.100176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nazimek J.M., Hunter M.D., Woodruff P.W. Auditory hallucinations: expectation-perception model. Med Hypotheses. 2012;78(6):802–810. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collerton D., Perry E., McKeith I. Why people see things that are not there: a novel perception and attention deficit model for recurrent complex visual hallucinations. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28(6):737–757. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000130. [discussion 57-94] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hugdahl K. "Hearing voices": auditory hallucinations as failure of top-down control of bottom-up perceptual processes. Scand J Psychol. 2009;50(6):553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jardri R., Hugdahl K., Hughes M. Are hallucinations due to an imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory influences on the brain? Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(5):1124–1134. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fletcher P.C., Frith C.D. Perceiving is believing: a Bayesian approach to explaining the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(1):48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrn2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller A.J., Shine J.M., Halliday G.M., Lewis S.J. Visual hallucinations in Parkinson's disease: theoretical models. Mov Disord. 2014;29(13):1591–1598. doi: 10.1002/mds.26004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powers A.R., III, Kelley M., Corlett P.R. Hallucinations as top-down effects on perception. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2016;1(5):393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho R., Wu W. Mechanisms of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia. Front Psych. 2013;4:155. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alderson-Day B., Diederen K., Fernyhough C. Auditory hallucinations and the Brain's resting-state networks: findings and methodological observations. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(5):1110–1123. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones S.R. Do we need multiple models of auditory verbal hallucinations? Examining the phenomenological fit of cognitive and neurological models. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(3):566–575. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rolland B., Jardri R., Amad A., Thomas P., Cottencin O., Bordet R. Pharmacology of hallucinations: several mechanisms for one single symptom? Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/307106. {Rolland, 2014 #81}. (307106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curcic-Blake B., Ford J.M., Hubl D. Interaction of language, auditory and memory brain networks in auditory verbal hallucinations. Prog Neurobiol. 2017;148:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garrison J.R., Fernyhough C., McCarthy-Jones S., Haggard M., Australian Schizophrenia Research B, Simons J.S. Paracingulate sulcus morphology is associated with hallucinations in the human brain. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8956. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muller V.I., Cieslik E.C., Laird A.R. Ten simple rules for neuroimaging meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;84:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen P., Aleman A., McGuire P.K. Inner speech models of auditory verbal hallucinations: evidence from behavioural and neuroimaging studies. International Review of Psychiatry. 2007;19(4):407–415. doi: 10.1080/09540260701486498. Abingdon, England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diederich N.J., Goetz C.G., Stebbins G.T. Repeated visual hallucinations in Parkinson's disease as disturbed external/internal perceptions: focused review and a new integrative model. Movement Disorders. 2005;20(2):130–140. doi: 10.1002/mds.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group P Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Radua J., Mataix-Cols D., Phillips M.L. A new meta-analytic method for neuroimaging studies that combines reported peak coordinates and statistical parametric maps. European Psychiatry. 2012;27(8):605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]