Abstract

Patient: Female, 22

Final Diagnosis: Acute respiratory distress syndrome

Symptoms: Flank pain • urinary frequency

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: ECMO

Specialty: Critical Care Medicine

Objective:

Unusual or unexpected effect of treatment

Background:

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), also known as extracorporeal life support (ECLS), is a technique used to provide prolonged cardiac and respiratory support to persons whose heart and lungs are unable to deliver adequate perfusion or gas exchange to sustain life.

It is indicated in patients with severe ARDS, severe hypothermia, and cardiac and respiratory failure when other conventional methods fail.

Case Report:

We report the case of a 22-year-old gravid 2 Para 1 woman who presented to the Emergency Department with pyelonephritis, who subsequently developed sepsis that progressed to ARDS. She was managed successfully with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO] for 5 days, with heparin used as an anticoagulant. After significant improvement, she was successfully de-cannulated and extubated.

Conclusions:

The use of ECMO in pregnancy and post-partum can be associated with several complications to both mother and fetus. With appropriate patient selection, good knowledge of the procedure, and early initiation, successful outcomes can be attained.

MeSH Keywords: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation; Pregnancy Complications; Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] can be diagnosed after cardiogenic pulmonary edema and alternative causes of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and bilateral infiltrates have been excluded. A moderate to severe impairment of oxygenation must be present, as defined by the ratio of arterial oxygen tension to fraction of inspired oxygen [PaO2/FiO2]. ARDS can be cause by many conditions, including but not limited to, sepsis.

V-V (venovenous) extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is indicated in patients who have hypoxemic respiratory failure, hypercarbic respiratory failure, respiratory failure in lung transplant, bronchopleural fistulas, pulmonary air leaks, or complex airway management.

ECMO is indicated for use in patient with severe ARDS, severe hypothermia, and cardiac and respiratory failure when other convention methods have failed. The use of ECMO in cardiac and respiratory failure is gaining popularity in the USA, but, due to lack of personnel or equipment, only a few centers are able to perform it.

It is imperative to differentiate venovenous ECMO [VV ECMO] from venoarterial ECMO [VA ECMO]. VV ECMO works by extracting the carbon dioxide and oxygenating red blood cells [1]; blood is drained from the vena cava oxygenated outside of the body through the ECMO oxygenator and returned to the right atrium [2]. In VV ECMO, no cardiac support is provided, as opposed to venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [VA ECMO], which provides both cardiac and respiratory support. Major complications of ECMO include bleeding and infections.

Case Report

A 22-year-old old gravid woman presented to the Emergency Department at 33 weeks of gestation with 1-week history of dysuria. On examination, she was found to be febrile (body temperature 102.7°F [39.3°C]), tachycardia of 112 beats per minutes, and suprapubic and left-sided costovertebral angle tenderness. Blood pressure was 105/65mmHg. An obstetric examination was normal. She was admitted to the hospital for sepsis due to acute pyelonephritis. Lab tests revealed a leukocytosis of 15.0×103/mcl, urinalysis was positive for nitrites and leucocytes esterase, urine squamous cell was 4.8/UL, urine WBC was 566.8/UL, and urine bacteria was >10000/UL, which was consistent with urinary tract infection [UTI], and urine culture eventually was positive for Escherichia coli [E. coli]. Renal ultrasound revealed hyperechoic kidneys likely representing parenchymal disease renal disease. She was started on intravenous [IV] antibiotics (ceftriaxone 1 g/daily) and intravenous fluid. A blood culture was eventually positive for bacteremia with E. coli.

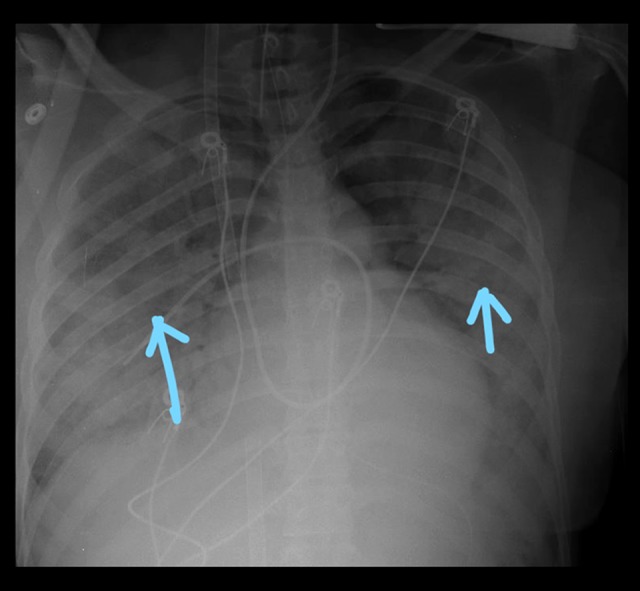

On the 2nd day of admission, the patient was noted to be in septic shock, as evidenced by persistent hypotension [blood pressures=70 s/40 mmHg], which was unresponsive to 4 liters of crystalloids fluids. She was also hypoxic, saturating at 70% on 6 L nasal cannula. A physical exam revealed diffused crackles and extremities warm to touch. Laboratory testing was pertinent for creatinine 1.43 mg/dL, Hb 10 g/dl, WBC 20×103/mcl, and lactic acid 9 mmol/L. She was subsequently intubated due to acute hypoxic respiratory failure and started on norepinephrine infusion at a rate of 2 mcg/min and titrated up to maintain a goal mean arterial pressure [MAP] of 65 and above. ABG showed PH 7.41/PCO2 33mmHg/PO2 60 mmHg on pressure-controlled ventilation [PRVC] of TV 350/RR18/FiO2 100/PEEP 10. Peak pressure was at 36 cmH2O. Fetal heart tracings at this time were reassuring. A chest x-ray revealed bilateral lung consolidation (Figure 1). While on mechanical ventilation with FiO2 of 100, she remained hypoxic, saturating at 70%, and ABG revealed a PO2 of 50 with a PaO2/FiO2 of 50, consistent with severe ARDS. Given her increasing oxygen requirement, a decision was made to initiate V-V ECMO. Pre-ECMO vital signs were blood pressure of 103/72mmHg on norepinephrine of 6 mcg/mins, oxygen saturation of 75% respiratory rate [RR] of 18, body temp of 99.3°F, and pulse rate of 102 bpm. A right femoral and a right internal jugular vein were placed at bedside via a 23F and a 19F cannula, respectively, and the cannulas were passed over an Amplatz wire with no difficulty. About 3 h after ECMO cannulation and initiation, fetal distress was noted, as evidenced by fetal heart deceleration requiring emergency cesarean section at bedside by the obstetric team, with delivery of a viable neonate. The newborn was admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit for close monitoring. A total of 5000 Units of heparin was given. Total blood loss from the cesarean section was about 100 ml. Anesthesia was achieved with fentanyl and versed drip. The ECMO circuit consisted of a Maquet Rotaflow centrifugal pump and a Maquet oxygenator.

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray revealed bilateral lung consolidation concerning for ARDS.

The patient was given broad-spectrum antibiotics using vancomycin 1250 mg every 12 h and cefepime 1 g every 12 h. During ECMO, the mechanical ventilation was reduced to FiO2 of 0.4 to prevent oxygen toxicity.

Initial ECMO settings were: pump speed initially was at 1500 revolution per minute [RPM] and then increased to 3000 RPM. The flow rate was 4 L per min [LPM], with a sweep of 5.5 LPM. The patient’s saturation was 96%. She was monitored for ECMO “chatter”, or instability of ECMO waveforms. The cannula site was examined daily for migration.

Anticoagulation for ECMO circuit was performed according to our institutional ECMO protocol with an initial bolus of heparin 100 IU/kg at the time of ECMO initiation followed by a continuous infusion of intravenous heparin, targeting an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 40–60 s.

The hemoglobin level was maintained above 10 g/dl, and she received a total of 4 units of PRBC while on ECMO. An initial ECHO showed an ejection fraction [EF] of 38% with mild left ventricular [LV] dilatation. She had moderate global and diffuse LV hypokinesis, mild RV dilatation, and mild RV dysfunction, but no pericardial effusion.

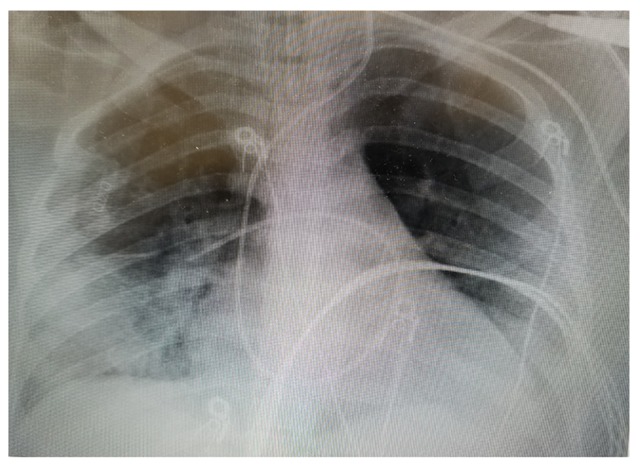

Given daily assessment and weaning, patient was successfully weaned off ECMO support and safely de-cannulated on day 5 of ECMO and subsequently extubated at 2 days after de-cannulation. Prior to extubation, a chest x-ray showed marked improvement in lung fields (Figure 2). Repeat ECHO showed an ejection fraction of 53% and no evidence of hemodynamically significant valve disease. No wall motion abnormality was detected. The patient was safely discharged after 13 days of admission, with no oxygen requirement. At the time of discharge, both mother and child where in good health.

Figure 2.

Interval improvement in previously seen bilateral consolidation.

Discussion

The severe ARDS and shock in our patient might have been due to an inflammation cascade triggered by the urosepsis. This inflammatory state damages the small vessels and causes fluid leakage, resulting in impaired gaseous exchange in the alveoli. Mortality is usually high in patients with ARDS and sepsis. VV ECMO has become a modality of choice for effectively oxygenating and ventilating patients with ARDS, with relatively low risk to the patient when conventional methods of mechanical ventilation fail to provide adequate oxygenation.

ECMO can provide prolonged cardiac and respiratory support to patients with severe refractory cardio-pulmonary failure. In VV ECMO after cannulation, titration is set based on the patient’s hemodynamics, with the aim of maintaining oxygenation to the tissues while preventing stasis of blood. Frequent assessment is warranted and, when needed, is adjusted to provide adequate oxygenation. A recent multi-center trial reported improved survival in adults with reversible acute respiratory failure treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) compared with conventional ventilation [1,3].

It is indicated for use in hypoxic and hypercapnic respiratory failure, septic shock, and as a bridge to heart and lung transplant. In adults, studies indicate increased survival and rapidly growing use of ECMO [4,5].

Extracorporeal life-support therapy in nonpregnant patients has been shown to be safe when used in carefully selected individuals [6]; however, during pregnancy and in the postpartum period, it is thought to be associated with an increased risk for maternal or fetal bleeding complications and amniotic fluid embolism [6].

A case series of 4 patients [7] reported survival of all 4 mothers and 3 of the 4 fetuses [8].

The largest literature review to date showed a mortality rate of 11.1%, with only 2 patients not surviving hospital discharge, and fetal survival was 100%; one-third of the patients in the cohort had bleeding as a complication of their ECMO, and other complications noted were DIC and occlusive and non-occlusive deep vein thromboses.

In our case, the following factors may have been attributed to her success in V-V ECMO: (1) young age; (2) previous pregnancy with no complication; (3) good identification and source control of her infection, and her acute pyelonephritis was identified early and antibiotic was started immediately, with fluid to maintain perfusion; (4) she was also managed at an advanced lung and heart transplant center with good knowledge of ECMO use and a good maternal-fetal care center; and (5) early initiation of VV ECMO. Identifying the cause of ARDS and appropriate treatment is also paramount in patient care and leads to successful outcomes.

Patient selection is vital prior to initiating this expensive procedure. Younger patients and patients with treatable conditions have a better outcome [9]. It should also be done in a center with ECMO capabilities and physician and nurses with good knowledge of the procedure, as this will improve the outcome.

The risk vs. benefit ratio must be assessed before ECMO is initiated in this group of patients.

Early application of ECMO may help to avoid substantial lung and sequential organ dysfunction through the inhibition of systemic release of inflammatory mediators induced by high concentrations of oxygen and high-volume ventilation [10–12].

Although widely used, the efficacy of venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in patients with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) remains controversial, as evident by the EOLIA trail [13]. Indications that a patient can be safely de-cannulated are improvement in radiographic appearance, pulmonary compliance, and adequate oxygenation.

Conclusions

ECMO use in pregnancy is relatively safe; however, we recommend careful selection of gravid and postpartum women prior to initiation of ECMO. It should also be performed in a center and by physician with adequate knowledge of ECMO use. This will help improve outcome. Early application of ECMO may help improve outcome. More data is needed to ascertain the plethora effect with V-V ECMO in this patient population.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Peek GJ, Clemens F, Elbourne D, et al. CESAR: Conventional ventilatory support vs. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:163. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang D, Zhou X, Liu X, et al. Wang-Zwische double lumen cannula – toward a percutaneous and ambulatory paracorporeal artificial lung. ASAIO J. 2008;54(6):606–11. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31818c69ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peek GJ, Elbourne D, Mugford M, et al. Randomized controlled trial and parallel economic evaluation of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR) Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(35):1–46. doi: 10.3310/hta14350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang CH, Chen HC, Caffrey JL, et al. Survival analysis after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in critically ill adults: A nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2016;133:2423–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Power CA, Van Heerden PV, Moxon D, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for critically ill patients with influenza A (H1N1) 2009: A case series. Crit Care Resusc. 2011;13:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimme I, Winter R, Kluge S Petzoldt M. Hypoxic cardiac arrest in pregnancy due to pulmonary haemorrhage. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006741. pii: bcr2012006741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agerstrand C, Abrams D, Biscotti M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiopulmonary failure during pregnancy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:774–79. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma NS, Wille KM, Bellot SC, Diaz-Guzman E. Modern use of extracorporeal life support in pregnancy and post-partum. ASAIO J. 2015;61:110–14. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser JF, Shekar K, Diab S, et al. ECMO – the clinician’s view. ISBT Sci Ser. 2012;7:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Combes A, Bacchetta M, Brodie D, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure in adults. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:99–104. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834ef412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacLaren G, Combes A, Bartlett RH. Contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult respiratory failure: Life support in the new era. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:210–20. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marasco S, Lukas G, McDonald M, et al. Review of ECMO (extra corporeal membrane oxygenation) support in critically ill adult patients. Heart Lung Circ. 2008;17S:S41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]