This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the association between parent training and language and communication outcomes for young children.

Key Points

Question

What is the association of parent training with language and communication outcomes for young children?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 76 studies found that parent-implemented language interventions were associated with language development in children with or at risk of language impairment. Moderate positive associations were found for child outcomes, and strong associations were found for parent outcomes.

Meaning

The findings suggest that language interventions that include parent training are associated with communication-related outcomes in young children, which may have implications for prevention and intervention in various populations of parent-child dyads.

Abstract

Importance

Training parents to implement strategies to support child language development is crucial to support long-term outcomes, given that as many as 2 of 5 children younger than 5 years have difficulty learning language.

Objective

To examine the association between parent training and language and communication outcomes in young children.

Data Sources

Searches of ERIC, Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, and PsycARTICLES were conducted on August 11, 2014; August 18, 2016; January 23, 2018; and October 30, 2018.

Study Selection

Studies included in this review and meta-analysis were randomized or nonrandomized clinical trials that evaluated a language intervention that included parent training with children with a mean age of less than 6 years. Studies were excluded if the parent was not the primary implementer of the intervention, the study included fewer than 10 participants, or the study did not report outcomes related to language or communication.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

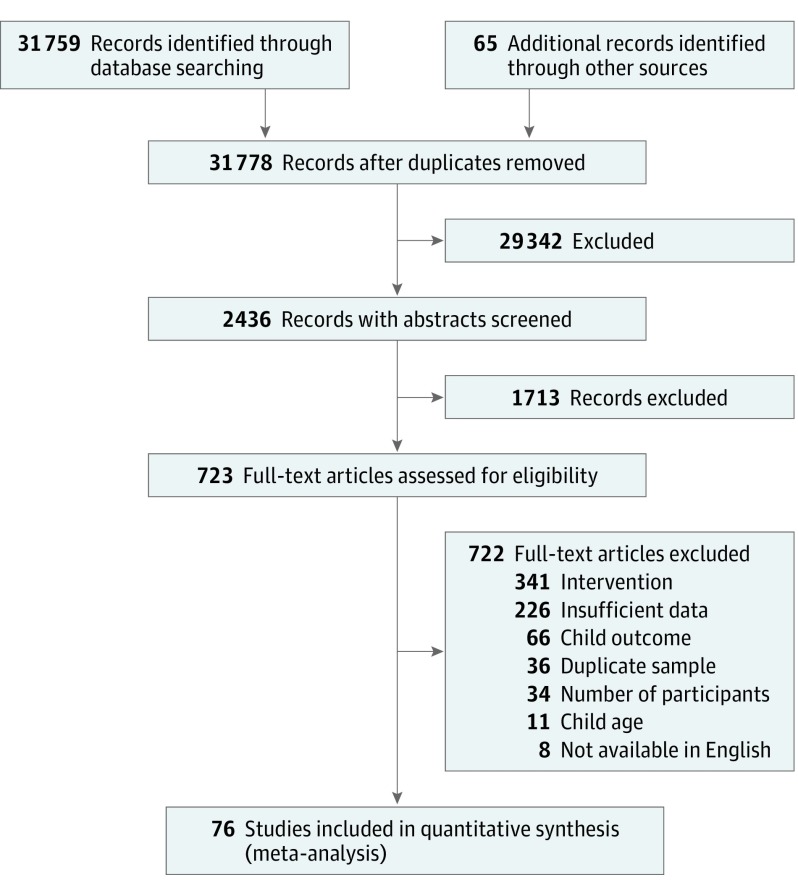

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were applied to a total of 31 778 articles identified for screening, with the full text of 723 articles reviewed and 76 total studies ultimately included.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Main outcomes included language and communication skills in children with primary or secondary language impairment and children at risk for language impairment.

Results

This meta-analysis included 59 randomized clinical trials and 17 nonrandomized clinical trials including 5848 total participants (36.4 female [20.8%]; mean [SD] age, 3.5 [3.9] years). The intervention approach in 63 studies was a naturalistic teaching approach, and 16 studies used a primarily dialogic reading approach. There was a significant moderate association between parent training and child communication, engagement, and language outcomes (mean [SE] Hedges g, −0.33 [0.06]; P < .001). The association between parent training and parent use of language support strategies was large (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.55 [0.11], P < .001). Children with developmental language disorder had the largest social communication outcomes (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.37 [0.17]); large and significant associations were observed for receptive (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.92 [0.30]) and expressive language (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.83 [0.20]). Children at risk for language impairments had moderate effect sizes across receptive language (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.28 [0.15]) and engagement outcomes (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.36 [0.17]).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that training parents to implement language and communication intervention techniques is associated with improved outcomes for children and increased parent use of support strategies. These findings may have direct implications on intervention and prevention.

Introduction

The World Health Organization has identified language as 1 of the domains of development that is associated with not only early learning and academic success but also economic participation and health across the lifespan.1 The work of James J. Heckman, Nobel laureate in economics, suggests that deficits in early development are associated with reduced long-term productivity and increased social costs.2 Early childhood is a critical period of rapid brain growth and heightened neuroplasticity.3 It is during this period that young children are the most efficient and effective language learners. Thus, it is not surprising that interventions delivered during this critical period have the highest financial return on investment.2

Most children learn communication skills (eg, pointing, gesturing) and language skills (eg, saying words, following directions) from high-quality interactions with their parents and caregivers. However, some children may experience difficulties learning language for any number of different reasons, including genetic, neurologic, and environmental. Language impairment is defined as persistent difficulty in the acquisition or use of written or spoken language that is substantially below age expectations.4 As many as 12% of children between 2 and 5 years of age may exhibit a developmental language delay as a primary condition (ie, not attributable to any other identifiable cause),5 and an additional 13% may exhibit a language impairment as a secondary condition that is the result of an identifiable disorder (eg, cognitive delay, hearing loss, and autism spectrum disorder).6 Furthermore, as many as 65% of children from low socioeconomic backgrounds exhibit clinically significant language impairment.7 With 21% of US children living in poverty,8 this is equivalent to an additional 14% of children with language delays associated with environmental factors. Taken together, these findings suggest that as many as 2 of 5 children younger than 5 years experience difficulty learning language; this is nearly twice the rate of childhood obesity,9 which is widely recognized as a public health crisis.10

It has been suggested that language impairment should be considered a public health problem11 given (1) the long-term burden of language impairment (ie, children with language impairment are more likely to have mental health problems,12 have fewer vocational opportunities,13 and become incarcerated14); (2) the uneven distribution of language impairment (ie, children living in poverty are more likely to have difficulty learning language)7; and (3) the positive association of intervention with improving language outcomes.15 Given that children learn language through social interactions with their parents and caregivers, most early intervention efforts have focused on teaching parents to use specific strategies to support their child’s language development. Furthermore, including parents in early language intervention is a cost-effective way to increase the amount of intervention the child receives compared with practitioner-delivered intervention.16

Previous syntheses of the literature on the association of parent training with child language outcomes have been restricted to specific populations, such as late talkers,15,17 children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD),17,18,19,20 children who are deaf or hard of hearing,21 and children with disruptive behavior.22 To date, no review has examined the effectiveness of teaching parents to use strategies to support their child’s language development across all populations of children with or at risk of language impairment. Therefore, the purpose of this current systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the association of parent training with language development in children with or at risk for language impairment. The specific research questions include the following: (1) What is the association between parent training and language and communication outcomes in young children? (2) What is the association between parent training and parent use of language support strategies? (3) What child and intervention characteristics moderate intervention outcomes? (4) Do study variables (eg, measure type or diagnosis) moderate intervention outcomes?

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

We included randomized and nonrandomized studies in which parents were taught to use specific strategies to support their child’s language or communication and in which the control group did not receive an experimental intervention. Given our focus on early childhood, we only included studies in which the mean age of study participants was younger than 6 years. More information about inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in Table 1. A complete review protocol is available from the first author (M.Y.R.) on request.

Table 1. Participants, Intervention, Outcomes, Comparison, and Study Design Search Terms and Criteria.

| Variable | Search Terms | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | (child or infant or toddler) AND (parent or mother or caregiver) | Participants younger than 6 y | Mean age of participants older than 6 y (or mean age reported plus 1 SD was >6 y) |

| Intervention | AND (interactio* OR synchron* OR sensitiv* OR responsiv* OR facilitation OR input OR strategy OR communicative behavior OR parent behavior OR caregiver behavior OR mother behavior OR interaction) | Parent training in language or related behaviors; parent was primary implementer | Pharmaceutical interventions; therapist-implemented treatments in which parent training occurs in <50% of total intervention time |

| Comparison | AND (language OR communicat* OR vocabulary OR joint attention or joint engagement OR verbal behavior). | No treatment; business-as-usual control group; minimal treatment (<1 h of training per month) | Parent training in language strategies; language intervention delivered by research staff |

| Outcome | AND (language OR communicat* OR vocabulary OR joint attention OR joint engagement OR verbal behavior) | Any measure of language, communication, speech, engagement, play, or verbal skills | Social behavior with peers, complex or social play skills, brain-based measures, biological measures |

| Study design | Search criteria were not restricted for design | Treatment-control design | Single case; group design with <10 participants per group at baseline; treatment-treatment comparison |

Information Sources

An a priori systematic search for articles published in the following 4 databases were selected for this review: ERIC, Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, and PsycARTICLES. Inclusion of unpublished work (ie, gray literature) or missed references was attempted by reviewing references of included studies and forward searching relevant references (65 unique records identified) and by searching Academic Search Complete to identify dissertations and theses.

Search and Study Selection

The search was conducted on August 11, 2014; August 18, 2016; January 23, 2018; and October 30, 2018 (Table 1). The Participants, Intervention, Outcomes, Comparison, and Study Design23 framework was used to outline the search criteria and search terms. A doctoral student (B.J.S.) and a postdoctoral fellow (L.H.H.) rated all relevant titles for inclusion. Data were managed using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools.24 Six coders coded all abstract and full-text inclusion material with 20% overlap to measure interobserver agreement. Agreement on abstract and full-text inclusion exceeded 98%, and disagreements were reviewed by 1 of the authors (L.H.H.) for a final inclusion decision.

Data Collection Process

All studies that met the inclusion criteria were coded by 2 raters (B.J.S., L.H.H., and others) trained to 90% agreement across all variables. Across all rated items for all studies (n = 2690), mean agreement on categorical variables during initial coding exceeded 90%, and agreement on all calculations was 97%. All disagreements were resolved through consensus coding and verified by a primary author (L.H.H.). Disagreements were attributable to (1) miscalculations, (2) unidentified outcome, or (3) different interpretations of a definition.

Variables

Descriptive Measures

All study variables are defined and summarized in eTable 1 in the Supplement. We coded study features (eg, year published, type of publication), intervention characteristics (eg, frequency, length, and strategies taught to parents), and participant characteristics (eg, age, biological sex, race/ethnicity, and reason for language impairment).

Outcome Measures

Outcome data were extracted using means (SDs). When unavailable, 1-way F tests, 2-tailed unpaired t tests, χ2 tests, or means (SEs) were used. The postintervention outcome was estimated using the conservative, standardized Hedges g effect size correction for the small sample sizes included.25,26 A standardized metric allows comparison across different measure types and scales. When data were not available to calculate an effect size in the article, authors were emailed for additional information. Of the 3 authors emailed, only 1 replied, and he stated that the data were no longer available.

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias was rated using the Cochrane Collaboration indicators plus an indicator specifically for fidelity of intervention implementation (eTable 2 in the Supplement).18,27 Studies were rated as low risk (0 points), high risk (2 points), or unclear risk (1 point) for a total risk of bias score of 0 to 16 (eTable 2 in the Supplement). We examined total risk of bias score as a potential moderator of intervention outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Publication bias was examined using a funnel plot analysis and Eggers regression test to test the null hypothesis of small-study bias and to examine the potential publication bias across studies (eFigure in the Supplement).28 Effect size heterogeneity was also examined using τ2 as a measure of between study variance and I2 as a measure of the proportion of true heterogeneity to total effect size variance.

A robust variance estimate model was used to create a random-weights mean difference effect size of parent training on child language outcomes and parent use of language support strategies.29 All analyses were conducted in R-Studio, version 1.0.136 running R, version 3.3.3 using the robumeta package (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).30,31,32 A sensitivity analysis was used to evaluate the stability of the association across ρ values. Meta-regression estimation was used to examine the extent to which study variables influenced the mean standardized effect size (eg, bias score, length of intervention, and amount of parent training). Subgroup main effect and meta-regression analyses were conducted to analyze the separate effects based on language impairment type and measure type.

Results

Study Selection

A total of 31 778 unique records were identified and screened for eligibility (Figure). Of the articles that were screened, the full texts of 723 articles were screened for inclusion, and 76 total studies were included (A.P. Kaiser, T.B. Hancock, unpublished data, 1998).15,16,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105 Articles were excluded because of the reported age of participants (mean age plus 1 SD, >6 years; n = 11 studies), the inclusion of too few participants (n = 34 studies), the inclusion of nonparents as the primary interventionists (n = 343 studies), no reported measure of communication or language (n = 66 studies), no availability in English (n = 8 studies), or no reported statistics appropriate for calculating an effect size and no additional details or no author response to a request for information (n = 226 studies).

Figure. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Flow Diagram.

Study Characteristics

A summary of descriptive characteristics of included studies is provided in Table 2. Most studies were published in North America (n = 44 studies) and in peer-reviewed journals (n = 73 studies) between 1988 and 2018 and used a randomized trial design (n = 59 studies). Participants (n = 5848) were a mean (SD) of 3.5 (3.9) years old (range, 2 months to 5 years), and a mean (SD) of 36.4 (20.8%) were female. A total of 35 studies (48%) that reported race/ethnicity data included participants from the nonmajority race/ethnicity. Most studies included participants who were at risk for language impairment (eg, premature birth, low socioeconomic status) or participants who had ASD. The interventions lasted a mean of 23 weeks (median, 12 weeks; range, 4-120 weeks), and dosage ranged from monthly hour-long sessions up to 14 hours of parent training per week. Study-level descriptive information is available in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Descriptive Data of Included Articles.

| Variable | Articles, No. (%)a | All (N = 76)b | ASD (n = 27) | DLD (n = 10) | At Risk (n = 34) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Range | Articles, No. (%) | Mean (SD) | Patients, No. (%) | Mean (SD) | Articles, No. (%) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Peer-reviewed journal | 73 (96) | NA | NA | 24 (92) | NA | 10 (100) | NA | 34 (100) | NA |

| Country | |||||||||

| United States and Canada | 44 (57) | NA | NA | 17 (63) | NA | 6 (60) | NA | 19 (56) | NA |

| Europe | 20 (26) | NA | NA | 8 (30) | NA | 3 (30) | NA | 6 (18) | NA |

| Australia | 3 (4) | NA | NA | 1 (4) | NA | 1 (10) | NA | 1 (3) | NA |

| Malaysia | 1 (1) | NA | NA | 1 (4) | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA |

| Middle East | 2 (3) | NA | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 2 (6) | NA |

| South America | 2 (3) | NA | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 2 (6) | NA |

| Africa | 4 (5) | NA | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 4 (12) | NA |

| Publication year | 2010 | 1988-2018 | 2011 | 2004 | 2011 | ||||

| Before 2000 | 12 (16) | NA | NA | 1 (4) | NA | 4 (40) | NA | 4 (12) | NA |

| 2000-2009 | 12 (16) | NA | NA | 4 (15) | NA | 3 (30) | NA | 6 (18) | NA |

| 2010-2018 | 52 (68) | NA | NA | 22 (81) | NA | 3 (30) | NA | 24 (71) | NA |

| Randomized | 59 (78) | NA | NA | 19 (70) | NA | 7 (70) | NA | 25 (86) | NA |

| Risk of bias | NA | 3.8 (2.0) | 0-11 | NA | 3.1 (2.2) | NA | 4.7 (2.4) | NA | 3.9 (2.6) |

| Sample size | NA | 77 (78) | 20-501 | NA | 60 (31) | NA | 40 (24) | NA | 108 (105) |

| Participant age, y | NA | 3.53 (0.8) | 0.2-5.0 | 27 (100) | 4.36 (1.4) | 10 (100) | 2.97 (0.3) | 34 (100) | 2.75 (1.5) |

| Nonmajority race/ethnicity | 36 (47) | 48 (34) | 10-100 | 13 (50) | 37.6 (20) | 4 (40) | 51 (40) | 15 (44) | 58.3 (34) |

| Male | 70 (90) | 64 (21) | 46-97 | 23 (85) | 84 (6) | 10 (90) | 66 (12) | 26 (90) | 50 (16) |

| Mean IQ<85c | 15 (65) | 63.6 (5.1) | 53-74 | 11 (41) | 62.5 (5.2) | 0 (0) | NA | 0 (0) | NA |

| Primarily low-income socioeconomic status | 25 (33) | NA | NA | 3 (17) | NA | 1 (10) | NA | 19 (56) | NA |

| Parent educational level of high school or less | 24 (31) | NA | NA | 4 (20) | NA | 3 (30) | NA | 15 (44) | NA |

| Intervention length, wk | NA | 23 (24) | 4-120 | NA | 26 (18) | NA | 15 (6) | NA | 24 (33) |

| Intervention dose, mean h/wk | NA | 1.3 (1.6) | 0.1-14 | NA | 1.7 (2.5) | NA | 1.4 (0.8) | NA | 0.9 (0.5) |

| Intervention type | |||||||||

| Dialogic reading | 16 (21) | NA | NA | 1 (4) | NA | 2 (20) | NA | 12 (44) | NA |

| Naturalistic language | 63 (83) | NA | NA | 23 (85) | NA | 9 (90) | NA | 27 (78) | NA |

| Parent instruction | |||||||||

| Workshop | 17 (22) | NA | NA | 2 (7) | NA | 6 (60) | NA | 8 (24) | NA |

| Coaching | 49 (64) | NA | NA | 18 (67) | NA | 5 (50) | NA | 23 (68) | NA |

| Modeling | 21 (28) | NA | NA | 8 (30) | NA | 4 (40) | NA | 7 (21) | NA |

| No. of effect sizes | |||||||||

| Total effect sizes | 377 | NA | NA | 145 | NA | 72 | NA | 131 | NA |

| Expressive language | 149 | NA | NA | 31 | NA | 41 | NA | 65 | NA |

| Receptive language | 58 | NA | NA | 19 | NA | 9 | NA | 21 | NA |

| Social communication | 116 | NA | NA | 72 | NA | 13 | NA | 21 | NA |

| Engagement | 31 | NA | NA | 18 | NA | 0 | NA | 13 | NA |

| Parent implementation | 146 | NA | NA | 35 | NA | 4 | NA | 61 | NA |

| Fidelity reported | 36 (47) | NA | NA | 14 (54) | NA | 4 (36) | NA | 11 (32) | NA |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; DLD, developmental language disorder; NA, not applicable.

The percentage of articles includes those that have reported data.

All populations include ASD, DLD, at risk, and other (ie, children with hearing loss, children with cleft palate, children with an intellectual disability, and a mixed population of children).

Reported on a mean (SD) scale of 100 (15).

Intervention Characteristics

In 63 studies, parents were taught to use responsive and naturalistic strategies (ie, responding to child communication), and 16 studies used a dialogic reading approach (ie, asking questions and engaging in discussions during book reading). Forty-nine studies used a coaching approach, whereas 17 used workshops and 21 used therapist modeling. Only 36 studies measured parent use of the strategies taught during the intervention.

Risk of Bias

Across all studies, risk of bias was moderate (mean [SD], 3.8 [2.0]), and the overall risk of bias ranged from 0 to 11, on a scale of 0 to 16 points. Only 36 studies reported treatment fidelity, and the primary indicators of bias included not reporting masking of assessors or coders and not reporting allocation concealment (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Publication Bias

The funnel plot of mean effect sizes across studies revealed a symmetrical plot with 4 outliers (eFigure in the Supplement). The Eggers test for asymmetry showed meaningful but nonsignificant asymmetry (z, 1.81; P = .07). However, individual tests of mean effect sizes across studies within each population and measure type revealed small and nonsignificant results for asymmetry (range of z, −1.40 to 1.11; P = .16 to P = .73).

Synthesis of Main Effects

Child Outcomes

Across all studies, controlling for within-study effect size correlations, the mean effect size for the association of parent training with communication, engagement, and language outcomes was moderate (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.33 [0.06], P < .001) (Table 3). The sensitivity analysis demonstrated stable outcomes across ρ values (range, 0.3425-0.3427). The between-study heterogeneity was small (τ2 = 0.05), and 18% of the unexplained variability was attributable to true and explainable heterogeneity between studies. Children with ASD had consistent and moderate outcomes across all measures (range of mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.09-0.55 [0.06-0.24]). Children with developmental language disorder (DLD) had the largest social communication outcomes (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.37 [0.17]); large and significant associations were observed for receptive (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.92 [0.30]) and expressive language (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.83 [0.20]), whereas all other measure types were not reported for this population. Children at risk for language impairments had moderate effect sizes across receptive language (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.28 [0.15]) and engagement outcomes (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.36 [0.17]). All the outcomes reported for each study are available in eTable 5 in the Supplement.

Table 3. Mean Effect Size Across Measure Types and Populations.

| Variable | At Risk | DLD | ASD | Alla | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect Size (SE) [95% CI] | τ2b | I2b | No. of Outcomes/No. of Studies | Effect Size (SE) [95% CI] | τ2 | I2 | No. of Outcomes/No. of Studies | Effect Size (SE) [95% CI] | τ2 | I2 | No. of Outcomes/No. of Studies | Effect Size (SE) [95% CI] | τ2 | I2 | No. of Outcomes/No. of Studies | |||||

| Parent outcomes | 0.58 (0.10) [0.37 to 0.78]c | 0.22 | 42.68 | 61/18 | NAd | NAd | NA | NA | 0.44 (0.24) [−0.08 to 0.96]e | 0.80 | 74.57 | 35/15 | 0.55 (0.11) [0.33 to 0.78]c | 0.51 | 63.90 | 146/41 | ||||

| Expressive language | 0.22 (0.08) [0.04 to 0.41]e | 0 | 3.55 | 65/28 | 0.83 (0.20) [0.38 to 1.29]c | 0.10 | 21.15 | 41/9 | 0.19 (0.08) [0.02 to 0.36]e | 0.11 | 29.50 | 31/17 | 0.28 (0.06) [0.15 to 0.40]c | 0 | 0 | 149/58 | ||||

| Receptive language | 0.28 (0.15) [0.00 to 0.60]e | 0.26 | 55.45 | 21/27 | 0.92 (0.30) [0.07 to 1.76]f | 0.14 | 27.53 | 9/5 | 0.09 (0.08) [−0.08 to 0.27] | 0 | 0 | 19/15 | 0.29 (0.10) [0.09 to 0.48]c | 0.13 | 34.65 | 58/43 | ||||

| Social communication | 0.18 (0.11) [0.00 to 0.43] | 0 | 0 | 21/11 | 0.37 (0.17) [−0.1 to 0.93]e | 0.17 | 33.67 | 13/4 | 0.21 (0.08) [0.05 to 0.40]f | 0.07 | 2.82 | 72/25 | 0.24 (0.06) [0.13 to 0.35]c | 0 | 0 | 116/44 | ||||

| Engagement, attention | 0.36 (0.17) [−0.10 to 0.83]e | 0 | 0 | 13/6 | NAd | NAd | NA | NA | 0.55 (0.14) [0.26 to 0.85]c | 0.07 | 22.24 | 18/14 | 0.49 (0.11) [0.27 to 0.72]c | 0.04 | 15.23 | 31/20 | ||||

| All outcomes | 0.27 (0.09) [0.09 to 0.46]c | 0.07 | 24.48 | 131/34 | 0.82 (0.18) [0.40 to 1.23]c | 0.09 | 19.53 | 72/10 | 0.26 (0.06) [0.13 to 0.39]c | 0 | 1.14 | 145/27 | 0.33 (0.06) [0.22 to 0.45]c | 0.05 | 16.99 | 377/76 | ||||

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; DLD, developmental language disorder; NA, not analyzed.

All populations include ASD, DLD, at risk, and other (ie, children with hearing loss, children with cleft palate, children with an intellectual disability, and a mixed population of children).

τ2 And I2 are not directly comparable across nonnested models. No comparisons in this table are nested.

P < .001.

Too few effect sizes to calculate a stable effect size estimate.

P < .10.

P < .01.

Parent Outcomes

Across all studies that reported parent outcomes, the effect size for the association of parent training with parent use of language support strategies was large (mean [SE] Hedges g, 0.55 [0.11]; P < .001). This pattern of results was observed across each subgroup such that parents across all groups used more language support strategies than parents in the control group.

Moderator Analysis

None of the descriptive variables (ie, risk of bias, publication type, intervention type, and age of participants) was significantly associated with the mean effects across studies, and controlling for each of these descriptive variables did not increase the explained heterogeneity in the overall estimate. In addition, intervention characteristics (eg, dialogic reading, workshop instruction, naturalistic language, and directive) was not significantly associated with effects across studies and did not increase explained heterogeneity in the overall estimate. When examining type of language impairment as a binary factor associated with all outcomes (ie, DLD vs all other children), DLD was the only factor associated with child outcomes; children with DLD had significantly better outcomes than other children after parent training (mean [SE] β, 0.51 [0.19]).

Discussion

Findings from this systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate overall positive associations of parent training with child language outcomes and parent use of language support strategies. With instruction, parents can successfully learn to implement language support strategies, which has a subsequent positive association with child language skills. Intervention characteristics (eg, length, frequency, and type) were not associated with intervention outcomes; however, this finding may be attributable to the collinearity among variables (ie, children with ASD are the most impaired and receive the most intervention).

Given the importance of early language development in long-term academic and societal outcomes coupled with the empirical support for teaching parents to use language support strategies, it is critical to understand the best ways to involve parents early in their child’s language development. Law and colleagues11 proposed a prevention model for language impairment that is mapped to a public health intervention approach (ie, a tiered approach that includes primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention methods). Primary or universal prevention methods include the entire population of young children and focus on preventing the development of future language impairment. Primary prevention methods include raising awareness about the long-term sequelae of language impairments, highlighting the importance of supporting early language development, and delivering low-intensity, low-cost interventions in primary care settings, such as the Reach Out and Read program that occurs during well-child visits. However, results of a recent systematic review106 of primary care interventions for early development found that only 2 primary care interventions (ie, The Video Interaction Project107,108 and Healthy Steps for Young Children109) examined child language outcomes. Neither of these interventions had significant associations with child language outcomes. These results may occur because these low-dose interventions focus on many areas of development (eg, cognitive, social emotional, and language), such that each domain receives minimal attention.

Secondary or targeted prevention methods provide intervention for children who are at risk for language impairment, with the goal of preventing a clinically significant language impairment. Targeted primary care prevention methods related to early child development have focused primarily on disruptive behaviors (eg, Triple P, Incredible Years).110 Studies in this review that included a targeted prevention approach were primarily conducted at home, at school, or in groups at a research site.

Tertiary prevention or specialist intervention approaches include children who are likely to have persistent language impairments or children who have not responded to a secondary prevention approach. The focus of tertiary or specialist intervention approaches is to reduce the adverse effects of language impairments and increase participation rather than eliminate the language impairment. Most studies in this review (74%) included a specialist intervention approach in which parents were taught by a specialist (eg, speech-language pathologist, PhD student, or social worker). Future research should test the association of an integrated public health approach with language impairment that systematically examines the effects of 3 prevention methods (ie, primary, secondary, and tertiary) at a population level (eg, all infants and toddlers).

This tiered approach to intervention should include careful consideration of what and how parents are taught. For example, many studies in this systematic review included teaching parents to use many different language support strategies, with responsiveness as the most commonly taught intervention strategy. A primary prevention intervention approach for language might include teaching parents only 1 strategy, such as responsiveness, and using a low-cost method, such as video models and a printed handout. A secondary prevention intervention approach might include teaching parents to use a single strategy but with more support (eg, video feedback) or more strategies with less support. A tertiary intervention approach would likely include more instructional support and teaching more strategies to have a maximal influence on those children most likely to have persistent language learning difficulties. Tertiary approaches should also be tailored to account for individual differences in child factors, such as type of language impairment. For example, ASD is often distinguished from primary language impairments by differences in social communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviors or interests.4 These differences should be considered when deciding which specific strategies to teach to parents. For example, the focus for parents of children with ASD might be pointing and eye contact, whereas the focus for parents of children with primary language impairment might be complex syntax. Understanding the ideal combinations of instructional approaches and language support strategies is critical for maximizing the association of parent training with child outcomes.

In addition to evaluating a tiered intervention approach, future research should also examine barriers to implementation. For example, early intervention specialists spend less than 30% of their session time teaching parents to use specific strategies.111 Understanding reasons for infrequent inclusion of parents in early language intervention is critical to maximizing the uptake of evidence-based interventions that involve teaching parents to use language support strategies.

Strengths and Limitations

The results of a meta-analysis should be considered in light of the strengths and limitations of the meta-analysis and the body of work that comprises the meta-analysis. First, the use of robust variance estimation in the current study is an ideal method of analysis for these data. Traditional meta-analytic techniques require that each study provide a single, independent effect size. Because many of the studies included in this meta-analysis provided several outcome measures for each measured construct, traditional methods would be unable to accurately model all available data. Although synthetic effect sizes can be derived by combining multiple measures from the same study, to accurately model the effect size estimation errors, the exact covariance structure between each dependent measure in each study must be known.26 Because these data are rarely available, the error structure of synthetic effect sizes is most likely to be inaccurate, biasing the results of any subsequent meta-analysis. In contrast to these approaches, robust variance estimation allows for the inclusion of multiple dependent effect sizes from the same study with unknown covariance structures. An assumed correlation between dependent measures is used, and a sensitivity analysis checks for the effects of varying these assumed correlations. This method is ideal for the current study because it allows for the simultaneous inclusion of all collected data. Furthermore, this method allows for the inclusion of covariates in a meta-regression to determine whether these variables are significantly associated with the included effect sizes.

Second, the inclusion of children with varying degrees of language abilities and the moderator analyses allow for the examination of the association of parent training with language development for all young children and by specific subtypes. Across all parent training studies, there was a high representation of children with various types of language impairment and risk factors for language impairment (eg, siblings of children with ASD, children from low-income homes, and toddlers with challenging behaviors).

Third, although studies were conducted in a variety of locations (n = 14) and languages (n = 21), there were no studies in Asia, only a few in Central and South America, and only a few African studies outside South Africa. More research is needed across various cultural and linguistic groups. Furthermore, most studies failed to provide information on how parents were trained. Future research should examine the association of specific components of parent training with parent use of language support strategies. In addition, only half of the studies reported parent outcomes, and even fewer examined parent use of language support strategies as a mediator of child intervention outcomes. Future studies should report the specific parent training methods used to teach parents, the association of parent training with parent use of each language support strategy taught, and the association between parent use of each language support strategy and child language outcomes.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis revealed a positive association between parent training and child language and communication skills. These findings suggest that parent training should play a primary role in intervention and prevention programs to maximize language and communication outcomes for children with or at risk for language impairment.

eFigure. Funnel Plot

eTable 1. Definitions for Coded Items

eTable 2. Risk of Bias Definitions and Scoring Overview

eTable 3. Characteristics of Included Studies

eTable 4. Risk of Bias Scores for Included Studies

eTable 5. Child and Parent Outcomes for Included Studies

eReferences. Reference List for Included Studies

References

- 1.Siddiqi IL, Hertzman C. Early Child Development: A Powerful Equalizer. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heckman JJ. Schools, skills, and synapses. Econ Inq. 2008;46(3):289-324. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2008.00163.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown TT, Jernigan TL. Brain development during the preschool years. Neuropsychol Rev. 2012;22(4):313-333. doi: 10.1007/s11065-012-9214-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law J, Boyle J, Harris F, Harkness A, Nye C. Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: findings from a systematic review of the literature. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2000;35(2):165-188. doi: 10.1080/136828200247133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg SA, Smith EG. Rates of Part C eligibility for young children investigated by child welfare. Top Early Child Spec Educ. 2008;28(2):68-74. doi: 10.1177/0271121408320348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson KE, Welsh JA, Trup EMV, Greenberg MT. Language delays of impoverished preschool children in relation to early academic and emotion recognition skills. First Lang. 2011;31(2):164-194. doi: 10.1177/0142723710391887 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Children in Poverty Basic facts about low-income children. http://www.nccp.org/topics/childpoverty.html. Updated January 2018. Accessed November 5, 2018.

- 9.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806-814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karnik S, Kanekar A. Childhood obesity: a global public health crisis. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(1):1-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Law J, Reilly S, Snow PC. Child speech, language and communication need re-examined in a public health context: a new direction for the speech and language therapy profession. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2013;48(5):486-496. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snowling MJ, Bishop DVM, Stothard SE, Chipchase B, Kaplan C. Psychosocial outcomes at 15 years of children with a preschool history of speech-language impairment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(8):759-765. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01631.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law J, Rush R, Schoon I, Parsons S. Modeling developmental language difficulties from school entry into adulthood: literacy, mental health, and employment outcomes. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2009;52(6):1401-1416. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0142) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snow P, Powell M. Developmental language disorders and adolescent risk: a public-health advocacy role for speech pathologists? Adv Speech Lang Pathol. 2004;6(4):221-229. doi: 10.1080/14417040400010132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts MY, Kaiser AP. Early intervention for toddlers with language delays: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):686-693. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbard D, Coglan L, MacDonald J. Cost-effectiveness analysis of current practice and parent intervention for children under 3 years presenting with expressive language delay. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2004;39(2):229-244. doi: 10.1080/13682820310001618839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wake M, Tobin S, Girolametto L, et al. Outcomes of population based language promotion for slow to talk toddlers at ages 2 and 3 years: Let’s Learn Language cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2011;343:d4741. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hampton LH, Kaiser AP. Intervention effects on spoken-language outcomes for children with autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2016;60(5):444-463. doi: 10.1111/jir.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McConachie H, Diggle T. Parent implemented early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(1):120-129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00674.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meadan H, Ostrosky MM, Zaghlawan HY, Yu S. Promoting the social and communicative behavior of young children with autism spectrum disorders: a review of parent-implemented intervention studies. Top Early Child Spec Educ. 2009;29(2):90-104. doi: 10.1177/0271121409337950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson N, Martin P, Smith A, Thomas S, Aud AM, Ahmad A. Home visiting programs for families of children who are deaf or hard of hearing: a systematic review. J Early Hear Detect Interv. 2016;1(2):23-38. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundahl B, Risser HJ, Lovejoy MC. A meta-analysis of parent training: moderators and follow-up effects. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(1):86-104. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Impellizzeri FM, Bizzini M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: a primer. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7(5):493-503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. New York: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shadish WR, Rindskopf DM, Hedges LV. The state of the science in the meta-analysis of single-case experimental designs. Evid Based Commun Assess Interv. 2008;2(3):188-196. doi: 10.1080/17489530802581603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedges LV, Tipton E, Johnson MC. Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(1):39-65. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.RStudio RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Boston, MA: RStudio Inc; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher Z, Tipton E. robumeta: Robust Variance Meta-Regression. R Package, version 1.6. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aldred C, Green J, Adams C. A new social communication intervention for children with autism: pilot randomised controlled treatment study suggesting effectiveness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(8):1420-1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aram D, Fine Y, Ziv M. Enhancing parent–child shared book reading interactions: Promoting references to the book’s plot and socio-cognitive themes. Early Child Res Q. 2013;28(1):111-122. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnold DH, Lonigan CJ, Whitehurst GJ, Epstein JN. Accelerating language development through picture book reading: replication and extension to a videotape training format. J Educ Psychol. 1994;86(2):235. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.86.2.235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagner DM, Garcia D, Hill R. Direct and indirect effects of behavioral parent training on infant language production. Behav Ther. 2016;47(2):184-197. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Björn PM, Kakkuri I, Karvonen P, Leppänen PH. Accelerating early language development with multi-sensory training. Early Child Dev Care. 2012;182(3-4):435-451. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2011.646716 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boivin MJ, Nakasujja N, Familiar-Lopez I, et al. Effect of caregiver training on the neurodevelopment of HIV-exposed uninfected children and caregiver mental health: a Ugandan cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2017;38(9):753-764. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyce LK, Innocenti MS, Roggman LA, Norman VKJ, Ortiz E. Telling stories and making books: evidence for an intervention to help parents in migrant Head Start families support their children’s language and literacy. Early Educ Dev. 2010;21(3):343-371. doi: 10.1080/10409281003631142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brassart E, Schelstraete M-A. Simplifying parental language or increasing verbal responsiveness, what is the most efficient way to enhance pre-schoolers’ verbal interactions? J Educ Train Stud. 2015;3(3):133-145. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burgoyne K, Gardner R, Whiteley H, Snowling MJ, Hulme C. Evaluation of a parent-delivered early language enrichment programme: evidence from a randomised controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(5):545-555. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buschmann A, Jooss B, Rupp A, Feldhusen F, Pietz J, Philippi H. Parent based language intervention for 2-year-old children with specific expressive language delay: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(2):110-116. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.141572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter AS, Messinger DS, Stone WL, Celimli S, Nahmias AS, Yoder P. A randomized controlled trial of Hanen’s ‘More Than Words’ in toddlers with early autism symptoms. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(7):741-752. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02395.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casenhiser DM, Shanker SG, Stieben J. Learning through interaction in children with autism: preliminary data from asocial-communication-based intervention. Autism. 2013;17(2):220-241. doi: 10.1177/1362361311422052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang SM, Grantham-McGregor SM, Powell CA, et al. Integrating a parenting intervention with routine primary health care: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):272-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chao P-C, Bryan T, Burstein K, Ergul C. Family-centered intervention for young children at-risk for language and behavior problems. Early Child Educ J. 2006;34(2):147-153. doi: 10.1007/s10643-005-0032-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Colmar SH. A parent-based book-reading intervention for disadvantaged children with language difficulties. Child Lang Teach Ther. 2014;30(1):79-90. doi: 10.1177/0265659013507296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooper PJ, Vally Z, Cooper H, et al. Promoting mother–infant book sharing and infant attention and language development in an impoverished South African population: a pilot study. Early Child Educ J. 2014;42(2):143-152. doi: 10.1007/s10643-013-0591-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crain-Thoreson C, Dale PS. Enhancing linguistic performance: parents and teachers as book reading partners for children with language delays. Top Early Child Spec Educ. 1999;19(1):28-39. doi: 10.1177/027112149901900103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cronan TA, Cruz SG, Arriaga RI, Sarkin AJ. The effects of a community-based literacy program on young children’s language and conceptual development. Am J Community Psychol. 1996;24(2):251-272. doi: 10.1007/BF02510401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drew A, Baird G, Baron-Cohen S, et al. A pilot randomised control trial of a parent training intervention for pre-school children with autism: preliminary findings and methodological challenges. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;11(6):266-272. doi: 10.1007/s00787-002-0299-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fanning JL. Parent Training for Caregivers of Typically Developing, Economically Disadvantaged Preschoolers: An Initial Study in Enhancing Language Development, Avoiding Behavior Problems, and Regulating Family Stress. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fey ME, Warren SF, Brady N, et al. Early effects of responsivity education/prelinguistic milieu teaching for children with developmental delays and their parents. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006;49(3):526-547. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia D, Bagner DM, Pruden SM, Nichols-Lopez K. Language production in children with and at risk for delay: mediating role of parenting skills. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(5):814-825. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.900718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gibbard D. Parental-based intervention with pre-school language-delayed children. Eur J Disord Commun. 1994;29(2):131-150. doi: 10.3109/13682829409041488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ginn NC, Clionsky LN, Eyberg SM, Warner-Metzger C, Abner J-P. Child-directed interaction training for young children with autism spectrum disorders: parent and child outcomes. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(1):101-109. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1015135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Girolametto L, Pearce PS, Weitzman E. Interactive focused stimulation for toddlers with expressive vocabulary delays. J Speech Hear Res. 1996;39(6):1274-1283. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3906.1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glanemann R, Reichmuth K, Matulat P, Zehnhoff-Dinnesen AA. Muenster Parental Programme empowers parents in communicating with their infant with hearing loss. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77(12):2023-2029. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Green J, Charman T, McConachie H, et al. ; PACT Consortium . Parent-Mediated Communication-Focused Treatment in Children With Autism (PACT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9732):2152-2160. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60587-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Green J, Charman T, Pickles A, et al. ; BASIS team . Parent-mediated intervention versus no intervention for infants at high risk of autism: a parallel, single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(2):133-140. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00091-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guttentag CL, Landry SH, Williams JM, et al. “My Baby & Me”: effects of an early, comprehensive parenting intervention on at-risk mothers and their children. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(5):1482-1496. doi: 10.1037/a0035682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hadley PA, Rispoli M, Holt JK, et al. Input subject diversity enhances early grammatical growth: evidence from a parent-implemented intervention. Lang Learn Dev. 2017;13(1):54-79. doi: 10.1080/15475441.2016.1193020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hammer CS, Sawyer B. Effects of a culturally responsive interactive book-reading intervention on the language abilities of preschool dual language learners: a pilot study. NHSA Dialog. 2016;19(2). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hardan AY, Gengoux GW, Berquist KL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Pivotal Response Treatment Group for parents of children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(8):884-892. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huebner CE. Promoting toddlers’ language development through community-based intervention. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2000;21(5):513-535. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(00)00052-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ibanez LV, Kobak K, Swanson A, Wallace L, Warren Z, Stone WL. Enhancing interactions during daily routines: a randomized controlled trial of a web-based tutorial for parents of young children with ASD. Autism Res. 2018;11(4):667-678. doi: 10.1002/aur.1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jaegermann N, Klein PS. Enhancing mothers’ interactions with toddlers who have sensory-processing disorders. Infant Ment Health J. 2010;31(3):291-311. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jocelyn LJ, Casiro OG, Beattie D, Bow J, Kneisz J. Treatment of children with autism: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate a caregiver-based intervention program in community day-care centers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19(5):326-334. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199810000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jørgensen LD. Parent-implemented focused stimulation in toddlers with cleft palate [PhD thesis]. Copenhagen, Denmark: University of Copenhagen; 2017.

- 70.Kasari C, Gulsrud A, Paparella T, Hellemann G, Berry K. Randomized comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(3):554-563. doi: 10.1037/a0039080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kasari C, Gulsrud AC, Wong C, Kwon S, Locke J. Randomized controlled caregiver mediated joint engagement intervention for toddlers with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(9):1045-1056. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0955-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kasari C, Lawton K, Shih W, et al. Caregiver-mediated intervention for low-resourced preschoolers with autism: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2014;134(1):e72-e79. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kasari C, Siller M, Huynh LN, et al. Randomized controlled trial of parental responsiveness intervention for toddlers at high risk for autism. Infant Behav Dev. 2014;37(4):711-721. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2014.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keen D, Couzens D, Muspratt S, Rodger S. The effects of a parent-focused intervention for children with a recent diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder on parenting stress and competence. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2010;4(2):229-241. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Klassen KPO. Parent and child factors in an individualized language intervention: an evaluation study [thesis]. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: University of Toronto; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kotaman H. Impacts of dialogical storybook reading on young children’s reading attitudes and vocabulary development. Read Improv. 2013;50(4):199-204. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Landry SH, Smith KE, Swank PR, Zucker T, Crawford AD, Solari EF. The effects of a responsive parenting intervention on parent-child interactions during shared book reading. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(4):969-986. doi: 10.1037/a0026400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Landry SH, Zucker TA, Williams JM, Merz EC, Guttentag CL, Taylor HB. Improving school readiness of high-risk preschoolers: combining high quality instructional strategies with responsive training for teachers and parents. Early Child Res Q. 2017;40:38-51. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.12.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Law J, Kot A, Barnett G. A comparison of two methods for providing intervention to three year old children with expressive/receptive language impairment. London, England: City University London; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lingwood J, Rowland C, Billington J Evaluating the effectiveness of a shared reading intervention: a randomised controlled trial. 2017.

- 81.Lonigan CJ, Whitehurst GJ. Relative efficacy of parent and teacher involvement in a shared-reading intervention for preschool children from low-income backgrounds. Early Child Res Q. 1998;13(2):263-290. doi: 10.1016/S0885-2006(99)80038-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McConachie H, Randle V, Hammal D, Le Couteur A. A controlled trial of a training course for parents of children with suspected autism spectrum disorder. J Pediatr. 2005;147(3):335-340. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.McConkey R, Truesdale-Kennedy M, Crawford H, McGreevy E, Reavey M, Cassidy A. Preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders: evaluating the impact of a home-based intervention to promote their communication. Early Child Dev Care. 2010;180(3):299-315. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Newnham CA, Milgrom J, Skouteris H. Effectiveness of a modified Mother-Infant Transaction Program on outcomes for preterm infants from 3 to 24 months of age. Infant Behav Dev. 2009;32(1):17-26. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oosterling I, Visser J, Swinkels S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the focus parent training for toddlers with autism: 1-year outcome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2010;40(12):1447-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pile EJ, Girolametto L, Johnson CJ, Chen X, Cleave PL. Shared book reading intervention for children with language impairment: using parents-as-aides in language intervention. Can J Speech-Lang Pathol Audiol. 2010;34(2). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Poslawsky IE, Naber FB, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Daalen E, van Engeland H, van IJzendoorn MH. Video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting adapted to autism (VIPP-AUTI): a randomized controlled trial. Autism. 2015;19(5):588-603. doi: 10.1177/1362361314537124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roberts J, Williams K, Carter M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of two early intervention programs for young children with autism: centre-based with parent program and home-based. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2011;5(4):1553-1566. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rogers SJ, Estes A, Lord C, et al. Effects of a brief Early Start Denver model (ESDM)-based parent intervention on toddlers at risk for autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(10):1052-1065. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schertz HH, Odom SL, Baggett KM, Sideris JH. Mediating parent learning to promote social communication for toddlers with autism: effects from a randomized controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(3):853-867. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3386-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schertz HH, Odom SL, Baggett KM, Sideris JH. Effects of joint attention mediated learning for toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: an initial randomized controlled study. Early Child Res Q. 2013;28(2):249-258. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sheridan SM, Knoche LL, Kupzyk KA, Edwards CP, Marvin CA. A randomized trial examining the effects of parent engagement on early language and literacy: the Getting Ready intervention. J Sch Psychol. 2011;49(3):361-383. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Siller M, Hutman T, Sigman M. A parent-mediated intervention to increase responsive parental behaviors and child communication in children with ASD: a randomized clinical trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(3):540-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sokmum S, Singh SJ, Vandort S. The impact of Hanen More Than Words programme on parents of children with ASD in Malaysia. Keberkesanan Program Hanen More Words Dalam Kalangan Ibu Bapa Yang Mempuny Anak ASDdi Malays. 2017;15(2):43-51. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Solomon R, Van Egeren LA, Mahoney G, Quon Huber MS, Zimmerman P. PLAY Project Home Consultation intervention program for young children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2014;35(8):475-485. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Strauss K, Vicari S, Valeri G, D’Elia L, Arima S, Fava L. Parent inclusion in Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention: the influence of parental stress, parent treatment fidelity and parent-mediated generalization of behavior targets on child outcomes. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(2):688-703. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Suskind DL, Leffel KR, Graf E, et al. A parent-directed language intervention for children of low socioeconomic status: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Child Lang. 2016;43(2):366-406. doi: 10.1017/S0305000915000033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tannock R, Girolametto L, Siegel LS. Language intervention with children who have developmental delays: effects of an interactive approach. Am J Ment Retard. 1992;97(2):145-160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Turner-Brown L, Hume K, Boyd BA, Kainz K. Preliminary efficacy of family implemented TEACCH for toddlers: effects on parents and their toddlers with autism spectrum disorder [published online May 30, 2016]. J Autism Dev Disord. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2812-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vally Z, Murray L, Tomlinson M, Cooper PJ. The impact of dialogic book-sharing training on infant language and attention: a randomized controlled trial in a deprived South African community. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56(8):865-873. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Van Tuijl C, Leseman PP, Rispens J. Efficacy of an intensive home-based educational intervention programme for 4-to 6-year-old ethnic minority children in the Netherlands. Int J Behav Dev. 2001;25(2):148-159. doi: 10.1080/01650250042000159 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Watson LR, Crais ER, Baranek GT, et al. Parent-mediated intervention for one-year-olds screened as at-risk for autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(11):3520-3540. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3268-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Weisleder A, Mazzuchelli DSR, Lopez AS, et al. Reading aloud and child development: a cluster-randomized trial in Brazil. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20170723. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wetherby AM, Woods JJ. Early Social Interaction Project for children with autism spectrum disorders beginning in the second year of life: a preliminary study. Top Early Child Spec Educ. 2006;26(2):67-82. doi: 10.1177/02711214060260020201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Whitehurst GJ, Falco FL, Lonigan CJ, et al. Accelerating language development through picture book reading. Dev Psychol. 1988;24(4):552. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.24.4.552 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Peacock-Chambers E, Ivy K, Bair-Merritt M. Primary care interventions for early childhood development: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20171661. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mendelsohn AL, Dreyer BP, Flynn V, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care to promote child development: a randomized, controlled trial. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2005;26(1):34-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mendelsohn AL, Valdez PT, Flynn V, et al. Use of videotaped interactions during pediatric well-child care: impact at 33 months on parenting and on child development. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):206-212. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3180324d87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Johnston BD, Huebner CE, Anderson ML, Tyll LT, Thompson RS. Healthy steps in an integrated delivery system: child and parent outcomes at 30 months. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(8):793-800. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.8.793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Piquero AR, Jennings WG, Diamond B, et al. A meta-analysis update on the effects of early family/parent training programs on antisocial behavior and delinquency. J Exp Criminol. 2016;12(2):229. doi: 10.1007/s11292-016-9256-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Campbell PH, Sawyer LB. Supporting learning opportunities in natural settings through participation-based services. J Early Interv. 2007;29(4):287-305. doi: 10.1177/105381510702900402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Funnel Plot

eTable 1. Definitions for Coded Items

eTable 2. Risk of Bias Definitions and Scoring Overview

eTable 3. Characteristics of Included Studies

eTable 4. Risk of Bias Scores for Included Studies

eTable 5. Child and Parent Outcomes for Included Studies

eReferences. Reference List for Included Studies