This survey study analyzes NHIS data from nearly 18 000 patients with a cancer diagnosis before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to evaluate patterns and patient-reported reasons for not having health insurance before and after the ACA.

Key Points

Question

What are self-reported reasons for not having insurance among cancer survivors before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)?

Findings

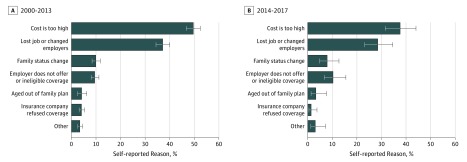

Among 17 806 nonelderly cancer survivors (2000-2017), 1842 (10.3%) self-reported not having health insurance (10.6% pre-ACA vs 6.2% post-ACA implementation in 2014), most commonly because of cost and unemployment, which both decreased after ACA implementation. Other reported reasons were employment related, family status change, aging out of a family plan, or refusal of coverage by an insurance company.

Meaning

Although cost remains the primary reason for not having insurance, more than half of cancer survivors self-reported other barriers to coverage.

Abstract

Importance

Cancer survivors experience difficulties in maintaining health care coverage, but the reasons and risk factors for lack of insurance are poorly defined.

Objective

To assess self-reported reasons for not having insurance and demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with uninsured status among cancer survivors, before and after implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2014.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This survey study analyzes National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data from January 1, 2000, through December 31, 2017. Included were adult participants (age, 18-64 years) reporting a cancer diagnosis; however, those with a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer were excluded.

Exposures

Insurance status.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Multivariable logistic regression was used to define the association between demographic and socioeconomic variables and odds of being uninsured. The prevalence of the most common self-reported reasons for not having insurance (cost, unemployment, employment-related reason, family-related reason) were estimated, with adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for each of the reasons defined by multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Among 17 806 survey participants, the mean (SD) age was 50.9 (10.8) years, and 6121 (34.4%) were men. A total of 1842 participants (10.3%) reported not having health insurance. Individuals surveyed in 2000 to 2013 had higher odds of not having insurance than those surveyed in 2014 to 2017 (10.6% vs 6.2%; aOR 1.75; 95% CI 1.49-2.08). Variables associated with higher odds of uninsured status included younger age (14.2% for age younger than mean vs 6.5% for age older than mean; aOR, 1.84; 95%, CI, 1.62-2.10), annual family income below the poverty threshold (21.4% vs 8.0%; aOR, 1.97; 95%, CI, 1.69-2.30), Hispanic ethnicity (18.8% vs 9.0%; aOR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.51-2.33), noncitizen status (24.3% vs 9.2%; aOR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.69-3.34), and current smoking (18.6% vs. 6.7%; aOR, 2.65; 95% CI, 2.32-3.02). Before the ACA, increasing interval from cancer diagnosis was associated with not having insurance (12.3% for ≥6 years vs 8.9% for 0-5 years; aOR, 1.47; 95% CI 1.26-1.70) as was black race (13.9% for black patients vs 10.4% for nonblack patients; AOR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.04-1.61), but after the ACA, they no longer were (6.8% for ≥6 years vs 5.6% for 0-5 years; aOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.82-1.54; and 6.9% for black patients vs 6.2% for nonblack patients; aOR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.46-1.43). The most commonly cited reason for not having insurance was cost, followed by unemployment, both of which decreased after ACA implementation (cost, 49.6% vs 37.6%, aOR [pre-ACA vs post-ACA], 0.62; 95% CI, 0.46-0.85; unemployment, 37.1% vs 28.5%; aOR 0.62; 95% CI, 0.45-0.87).

Conclusions and Relevance

The proportion of uninsured cancer survivors decreased after implementation of the ACA, but certain subgroups remained at greater risk of being uninsured. Cost was identified as the primary barrier to obtaining insurance, although more than half of cancer survivors reported other barriers to coverage.

Introduction

In 2016, there were an estimated 15.5 million cancer survivors in the United States, a number that is expected to increase to 20.3 million by 2026.1 Although access to health care services is essential for cancer patients as a part of long-term survivorship care,2,3,4 multiple studies have shown that this population experiences substantial barriers in obtaining timely and affordable health care, in part owing to lack of insurance.5,6,7 Noninsurance or underinsurance has been shown to be associated with worse cancer-specific and overall survival.8,9,10,11,12,13

In an effort to decrease the number of uninsured individuals in the United States, the Affordable Care Act was enacted in March 2010, with the majority of provisions becoming effective in January of 2014.14 These provisions included requiring individuals to have a minimum level of health insurance, prevention of coverage denial for preexisting conditions, increasing the age for coverage of children by their parents’ health insurance, and establishment of new insurance marketplaces, among others.15 By 2016, the number of uninsured individuals in the United States decreased to 28 million compared with 44 million in 2013, representing the largest change in health care coverage since the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.16 Although studies have shown that insurance among cancer patients and survivors has increased after implementation of the ACA,17,18,19 these individuals remain at greater risk for noninsurance than those without a diagnosis of cancer,18 and the reasons and risk factors for not having insurance among this population are poorly defined.

As such, we used a comprehensive nationwide database to identify in cancer survivors self-reported reasons for noninsured status, trends in not having insurance over time, and the patient characteristics associated with being uninsured.

Methods

Data Source

The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) is a cross-sectional household survey of noninstitutionalized civilian adults living in the United States assessing a wide range of health status and utilization measures.20 First administered in 1957, the NHIS uses a multistage probability design to ensure broad geographic representation. Sample weights are provided for each individual permitting inference on national prevalence. Harmonized data were obtained through the Integrated Health Interview Series.21

Study Cohort

Our study population included nonelderly adults (aged 18-64 years) sampled from January 1, 2000, through December 31, 2017, reporting a diagnosis of cancer. Specifically, participants were queried regarding their cancer history via the following question: “Have you ever been told you had cancer?” Among participants who answered yes, the type of cancer was recorded. Those who reported a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer were excluded, consistent with other studies of cancer survivors.18,22,23 Participants 65 years and older were excluded because Medicare eligibility did not significantly change with implementation of the ACA. Additional sociodemographic variables collected in the database and used in our analyses included age, sex, race, ethnicity, annual family income, marital status, highest education level, current smoking status, citizenship status, era of survey, region of residence, and number of years since cancer diagnosis.

Study Design

The primary end point of this study was insurance coverage status. The National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) created the recorded variable “health insurance coverage status” based on survey respondents to 6 component variables that queried participants regarding whether they had private insurance, military health insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, another state-sponsored health plan, or other government program.20 Those responding no to all 6 questions were classified as not having insurance.

The secondary end point of this study was reason for no insurance. Survey participants who reported not having insurance were further queried regarding their reason for no insurance and were allowed to choose up to 5 of 6 responses or “other.” These reasons included (1) unemployment (lost job or changed employers), (2) employment-related reason (the person’s employer did not offer coverage or the person was not eligible for coverage through their employer), (3) family-related (got divorced or separated, experienced the death of spouse or parent, got married), (4) aged out of the family plan (became ineligible because of age or left school), (5) too expensive (cost is too high), (6) was refused coverage (insurance company refused coverage), and (7) other.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics including demographic and socioeconomic variables were reported stratified by health insurance coverage status. Self-reported reasons for not having insurance were estimated before and after implementation of the ACA, and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for reporting the following 4 most common reasons were assessed by multivariable logistic regression using sociodemographic variables: (1) cost (n = 859), (2) unemployment (n = 662), (3) employment-related reason (n = 201) and (4) family-related reason (n = 188). Aging out of the family plan (n = 63) and insurance company refusing coverage (n = 68) were not assessed as end points owing to the smaller number of patients reporting these reasons precluding robust multivariable analysis.

The prevalence of noninsured status was estimated. Multivariable logistic regression defined aORs and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for not having insurance among the entire cohort and in the 2000-2013 (before implementation of the ACA) and 2014-2017 (after ACA implementation) subgroups. Variables included in the model were age, sex, race, ethnicity, annual family income, marital status, highest education level, current smoking status, citizenship status, era of survey, and years since cancer diagnosis.

The absolute percentage-point changes in rates of noninsured status by baseline participant characteristics between the 2000-2013 and 2014-2017 periods were estimated. The proportion of cancer survivors with each type of insurance coverage (private insurance, military health insurance, Medicaid, Medicare, other state-sponsored health plan, or other government program) in the 2000-2013 and 2014-2017 periods was also estimated.

Because the dependent coverage provision permitting individuals aged 18 to 26 years to remain on their parents’ insurance plans was implemented in September 2010, additional analyses estimating the prevalence of noninsured status among this cohort were conducted for before and after 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014. In addition, separate analyses were conducted stratifying the cohort into those diagnosed with cancer 2 years or less prior to survey administration (thus most likely to be undergoing active treatment) vs those diagnosed more than 2 years prior to survey administration to assess whether rates of noninsured status changed for these subgroups with implementation of the ACA.

Sample weighting stratified by year was used for all analyses to produce nationally representative estimates. Statistical testing was 2 sided, with α = .05. Analyses were performed with Stata/SE, version 15.1 (StataCorp). The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center deemed the study to be exempt from review and approval and from participant written informed consent given the use of public deidentified data.

Results

Self-reported Reasons for Not Having Insurance

Among 17 806 study participants, 1842 (10.3%) reported not having health insurance throughout the study period (Table 1). The most commonly cited reason for not having insurance was cost, but the proportion of noninsured cancer survivors reporting cost as a reason for noninsurance decreased after implementation of the ACA (49.6% vs 37.6%; aOR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.46-0.85; P = .003) (Figure 1, Table 2). Blacks were less likely than whites to report cost as a reason for not having insurance (38.9% vs 48.3%; aOR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.42-0.88; P = .01). After cost, the second most common reason was unemployment (lost job or changed employers), and similarly, the proportion reporting this reason decreased in the 2014-2017 period compared with the 2000-2013 period (37.1% vs 28.5%; aOR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.45-0.87; P = .005). Older patients were more likely to report unemployment, while individuals below the poverty threshold were less likely to report this reason (Table 2). The next most common reasons for not having insurance were employment related (employer did not offer insurance, or the participant was ineligible for coverage), reported by 9.5% and 10.3% of participants in the 2000-2013 vs 2014-2017 period (P = .44), followed by family status change, reported by 10.0% and 7.9% of participants in the 2000-2013 and 2014-2017 periods (P = .27), respectively. Family-related reasons were less commonly reported among older cancer survivors (Table 2). The least common reasons for not having insurance included aging out of the family plan, insurance company refusing coverage, and other, which were each chosen by less than 5% of study participants in either time interval (Figure 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Raw No. (Raw %/Weighted %)a (N = 17 806) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Insured (n = 15 964) | Not Insured (n = 1842) | |

| Age, y | ||

| 18-34 | 1451 (79.3/80.0) | 380 (20.7/20.0) |

| 35-44 | 2152 (84.1/86.0) | 407 (15.9/14.0) |

| 45-54 | 4548 (90.2/91.5) | 495 (9.8/8.5) |

| 55-64 | 7813 (93.3/93.9) | 560 (6.7/6.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5625 (91.9/92.6) | 496 (8.1/7.4) |

| Female | 10 339 (88.5/89.5) | 1346 (11.5/10.5) |

| Raceb | ||

| White | 14 105 (89.9/90.9) | 1579 (10.1/9.1) |

| Black | 1391 (87.0/87.5) | 208 (13.0/12.5) |

| Alaskan Native or American Indian | 164 (84.5/85.4) | 30 (15.5/14.6) |

| Asian | 304 (92.4/91.2) | 25 (7.6/8.8) |

| Ethnicityb | ||

| Non–Spanish-Hispanic-Latino | 14 857 (90.5/91.1) | 1568 (9.5/8.9) |

| Spanish-Hispanic-Latino | 1107 (80.2/82.4) | 274 (19.8/17.6) |

| Citizenship status | ||

| US citizen | 15 639 (90.1/90.9) | 1723 (9.9/9.1) |

| Non-US citizen | 325 (73.2/77.9) | 119 (26.8/22.1) |

| Region of residence | ||

| Northeast | 2701 (94.5/95.4) | 158 (5.5/4.6) |

| North Central/Midwest | 3768 (90.6/90.7) | 390 (9.4/9.3) |

| South | 5637 (86.5/87.9) | 879 (13.5/12.1) |

| West | 3858 (90.3/91.4) | 415 (9.7/8.6) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Noncurrent smoker | 12 208 (92.5/93.6) | 994 (7.5/6.4) |

| Current smoker | 3756 (81.6/81.3) | 848 (18.4/18.7) |

| Income | ||

| At or above poverty threshold | 13 819 (91.5/92.1) | 1287 (8.5/7.9) |

| Below poverty threshold | 2145 (79.4/78.7) | 555 (20.6/21.3) |

| Interval since diagnosis, y | ||

| 0-5 | 7246 (91.2/92.1) | 700 (8.8/7.9) |

| 6-10 | 3247 (89.5/90.8) | 383 (10.5/9.2) |

| ≥11 | 5471 (87.8/88.7) | 759 (12.2/11.3) |

| Year of survey | ||

| 2000-2013 | 11 362 (88.4/89.4) | 1496 (11.6/10.6) |

| 2014-2017 | 4602 (93.0/93.8) | 346 (7.0/6.2) |

| Type of insurancec | ||

| Private | 11 958 (74.9/72.2) | NA |

| Military | 695 (4.4/4.2) | |

| Medicaid | 2246 (14.1/11.1) | |

| Medicare | 1862 (11.7/9.7) | |

| Other government | 65 (0.4/0.4) | |

| Other state | 194 (1.2/1.1) | |

Sample weighting stratified by year was used for all analyses to produce nationally representative estimates.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported as captured by the National Health Interview Survey. Participants were asked whether they identified with 1 or more of the following racial groups: white, black/African American, Alaskan Native or American Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, or other Asian. Those reporting Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, or other Asian race were grouped as Asian. Participants were also asked whether they identified with 1 or more of the following ethnicities: not Hispanic/Spanish origin, Mexican, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban/Cuban American, Dominican (republic), Central or South American, other Latin American (type not specific), other Spanish, or multiple Hispanic. Those reporting any of the ethnicities, with exception of not Hispanic/Spanish origin, were categorized as Spanish-Hispanic-Latino.

Total column number exceeds the number with insurance because participants could list having multiple types of insurance. Column percentages provided.

Figure 1. Self-reported Reasons for Being Uninsured Among Uninsured Cancer Survivors in the United States, 2000-2013 vs 2014-2017.

Percentages for each era do not add to 100 because participants could select from 0 to 5 reasons or “other.”

Table 2. Multivariable Adjusted Odds for Reasons for Not Having Insurance Among 1842 Participants Without Insurance.

| Characteristic | Reason for Not Having Insurance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (n = 859) | Unemployment (n = 662) | Employment Related (n = 201) | Family Related (n = 188) | |||||

| aOR (95% CI) | P Value | aOR (95% CI) | P Value | aOR (95% CI) | P Value | aOR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| 18-34 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| 35-44 | 1.37 (0.95-1.97) | .10 | 1.63 (1.11-2.40) | .01 | 1.76 (1.00-3.12) | .05 | 0.35 (0.20-0.62) | <.001 |

| 45-54 | 1.39 (0.99-1.97) | .06 | 2.25 (1.56-3.24) | <.001 | 1.72 (0.98-3.03) | .06 | 0.32 (0.19-0.54) | <.001 |

| 55-64 | 1.37 (0.98-1.93) | .07 | 2.21 (1.54-3.15) | <.001 | 1.25 (0.71-2.22) | .44 | 0.26 (0.14-0.48) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Female | 0.98 (0.76-1.27) | .88 | 0.97 (0.74-1.27) | .84 | 1.06 (0.70-1.60) | .78 | 1.14 (0.70-1.89) | .59 |

| Racea | ||||||||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Black | 0.61 (0.42-0.88) | .009 | 1.00 (0.69-1.44) | .98 | 1.24 (0.67-2.30) | .49 | 1.21 (0.68-2.20) | .53 |

| Alaskan Native or American Indian | 0.85 (0.34-2.11) | .72 | 1.14 (0.41-3.11) | .80 | 0.17 (0.04-0.76) | .02 | 0.67 (0.13-3.40) | .63 |

| Asian | 1.70 (0.68-4.25) | .26 | 0.82 (0.24-2.78) | .76 | 0.16 (0.02-1.32) | .09 | 0.96 (0.11-8.65) | .97 |

| Ethnicitya | ||||||||

| Non–Spanish-Hispanic- Latino |

1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Spanish-Hispanic-Latino | 0.99 (0.67-1.48) | .98 | 0.82 (0.52-1.29) | .39 | 1.17 (0.62-2.19) | .63 | 0.57 (0.21-1.57) | .28 |

| Citizenship status | ||||||||

| US citizen | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Non-US citizen | 1.27 (0.70-2.32) | .43 | 0.47 (0.23-0.97) | .04 | 0.74 (0.33-1.62) | .45 | 1.39 (0.26-7.57) | .70 |

| Region of residence | ||||||||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| North Central/Midwest | 0.97 (0.61-1.55) | .90 | 0.68 (0.42-1.10) | .12 | 1.04 (0.49-2.20) | .09 | 1.35 (0.68-2.70) | .39 |

| South | 1.40 (0.92-2.13) | .12 | 0.75 (0.49-1.16) | .20 | 0.46 (0.22-0.96) | .04 | 0.54 (0.27-1.08) | .08 |

| West | 1.34 (0.85-2.12) | .20 | 0.49 (0.30-0.80) | .004 | 1.23 (0.58-2.63) | .59 | 1.05 (0.52-2.12) | .88 |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Noncurrent smoker | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Current smoker | 0.90 (0.71-1.16) | .43 | 0.88 (0.68-1.14) | .33 | 1.34 (0.92-1.93) | .13 | 1.03 (0.68-1.56) | .91 |

| Income | ||||||||

| At or above poverty threshold | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Below poverty threshold | 0.83 (0.64-1.08) | .16 | 0.59 (0.45-0.78) | <.001 | 0.71 (0.46-1.10) | .12 | 1.36 (0.89-2.08) | .16 |

| Interval since diagnosis, y | ||||||||

| 0-5 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| 6-10 | 0.80 (0.59-1.10) | .17 | 1.13 (0.81-1.57) | .47 | 1.00 (0.62-1.61) | .99 | 1.25 (0.74-2.10) | .41 |

| ≥11 | 1.09 (0.83-1.43) | .53 | 0.99 (0.75-1.30) | .93 | 1.05 (0.70-1.59) | .81 | 0.89 (0.57-1.39) | .62 |

| Year of survey | ||||||||

| 2010-2013 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| 2014-2017 | 0.62 (0.46-0.85) | .003 | 0.62 (0.45-0.87) | .005 | 1.23 (0.73-2.09) | .44 | 0.73 (0.41-1.28) | .27 |

Abbreviation: aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported as captured by the National Health Interview Survey. Participants were asked whether they identified with 1 or more of the following racial groups: white, black/African American, Alaskan Native or American Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, or other Asian. Those reporting Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, or other Asian race were grouped as Asian. Participants were also asked whether they identified with 1 or more of the following ethnicities: not Hispanic/Spanish origin, Mexican, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban/Cuban American, Dominican (republic), Central or South American, other Latin American (type not specific), other Spanish, or multiple Hispanic. Those reporting any of the ethnicities, with exception of not Hispanic/Spanish origin, were categorized as Spanish-Hispanic-Latino.

Trends and Predictors of Noninsurance

Participants surveyed in the 2000-2013 period (pre-ACA) had higher odds of not having insurance than those surveyed in the 2014-2017 period (post-ACA) (10.6% vs 6.2%; aOR; 1.75; 95% CI, 1.49-2.08; P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariable Adjusted Odds of Not Having Insurance Among All Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Entire Cohort (2000-2017) | Pre-ACA Implementation (2000-2013) | Post-ACA Implementation (2014-2017) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | P Value | aOR (95% CI) | P Value | aOR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18-34 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 35-44 | 0.68 (0.55-0.84) | <.001 | 0.67 (0.53-0.84) | <.001 | 0.73 (0.44-1.21) | .22 |

| 45-54 | 0.44 (0.36-0.54) | <.001 | 0.42 (0.34-0.53) | <.001 | 0.50 (0.31-0.81) | .01 |

| 55-64 | 0.35 (0.29-0.42) | <.001 | 0.33 (0.27-0.41) | <.001 | 0.39 (0.25-0.60) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Female | 1.13 (0.98-1.30) | .09 | 1.13 (0.97-1.32) | .13 | 1.15 (0.83-1.61) | .40 |

| Racea | ||||||

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.0 (Reference) | |||

| Black | 1.18 (0.96-1.45) | .11 | 1.29 (1.04-1.61) | .02 | 0.81 (0.46-1.43) | .47 |

| Alaskan Native or American Indian | 1.13 (0.63-2.02) | .68 | 1.27 (0.67-2.41) | .46 | 0.58 (0.15-2.31) | .44 |

| Asian | 1.11 (0.64-1.93) | .70 | 1.06 (0.55-2.05) | .86 | 1.40 (0.52-3.80) | .51 |

| Ethnicitya | 1 [Reference] | |||||

| Non–Spanish-Hispanic-Latino | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||||

| Spanish-Hispanic-Latino | 1.87 (1.51-2.33) | <.001 | 1.89 (1.48-2.41) | <.001 | 1.99 (1.22-3.24) | .01 |

| Citizenship status | ||||||

| US citizen | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Non-US citizen | 2.38 (1.69-3.34) | <.001 | 2.14 (1.44-3.18) | <.001 | 3.44 (1.76-6.73) | <.001 |

| Region of residence | ||||||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| North Central/Midwest | 1.94 (1.51-2.48) | <.001 | 1.91 (1.47-2.49) | <.001 | 2.05 (1.07-3.96) | .03 |

| South | 2.64 (2.11-3.30) | <.001 | 2.65 (2.09-3.36) | <.001 | 2.54 (1.37-4.68) | .003 |

| West | 1.89 (1.48-2.42) | <.001 | 2.07 (1.60-2.69) | <.001 | 1.16 (0.58-2.34) | .68 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Noncurrent smoker | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Current smoker | 2.65 (2.32-3.02) | <.001 | 2.51 (2.16-2.90) | <.001 | 3.35 (2.45-4.59) | <.001 |

| Income | ||||||

| At or above poverty threshold | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| Below poverty threshold | 1.97 (1.69-2.30) | <.001 | 1.86 (1.57-2.21) | <.001 | 2.36 (1.66-3.35) | <.001 |

| Interval since diagnosis, y | ||||||

| 0-5 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | |||

| 6-10 | 1.16 (0.98-1.38) | .08 | 1.19 (0.99-1.44) | .07 | 1.00 (0.67-1.50) | .98 |

| ≥11 | 1.58 (1.36-1.82) | <.001 | 1.68 (1.42-1.97) | <.001 | 1.19 (0.84-1.67) | .33 |

| Year of survey | ||||||

| 2014-2017 | 1 [Reference] | NA | ||||

| 2000-2013 | 1.75 (1.49-2.08) | <.001 | ||||

Abbreviations: ACA, Affordable Care Act; aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Race and ethnicity were self-reported as captured by the National Health Interview Survey. Participants were asked whether they identified with 1 or more of the following racial groups: white, black/African American, Alaskan Native or American Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, or other Asian. Those reporting Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, or other Asian race were grouped as Asian. Participants were also asked whether they identified with 1 or more of the following ethnicities: not Hispanic/Spanish origin, Mexican, Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban/Cuban American, Dominican (republic), Central or South American, other Latin American (type not specific), other Spanish, or multiple Hispanic. Those reporting any of the ethnicities, with exception of not Hispanic/Spanish origin, were categorized as Spanish-Hispanic-Latino.

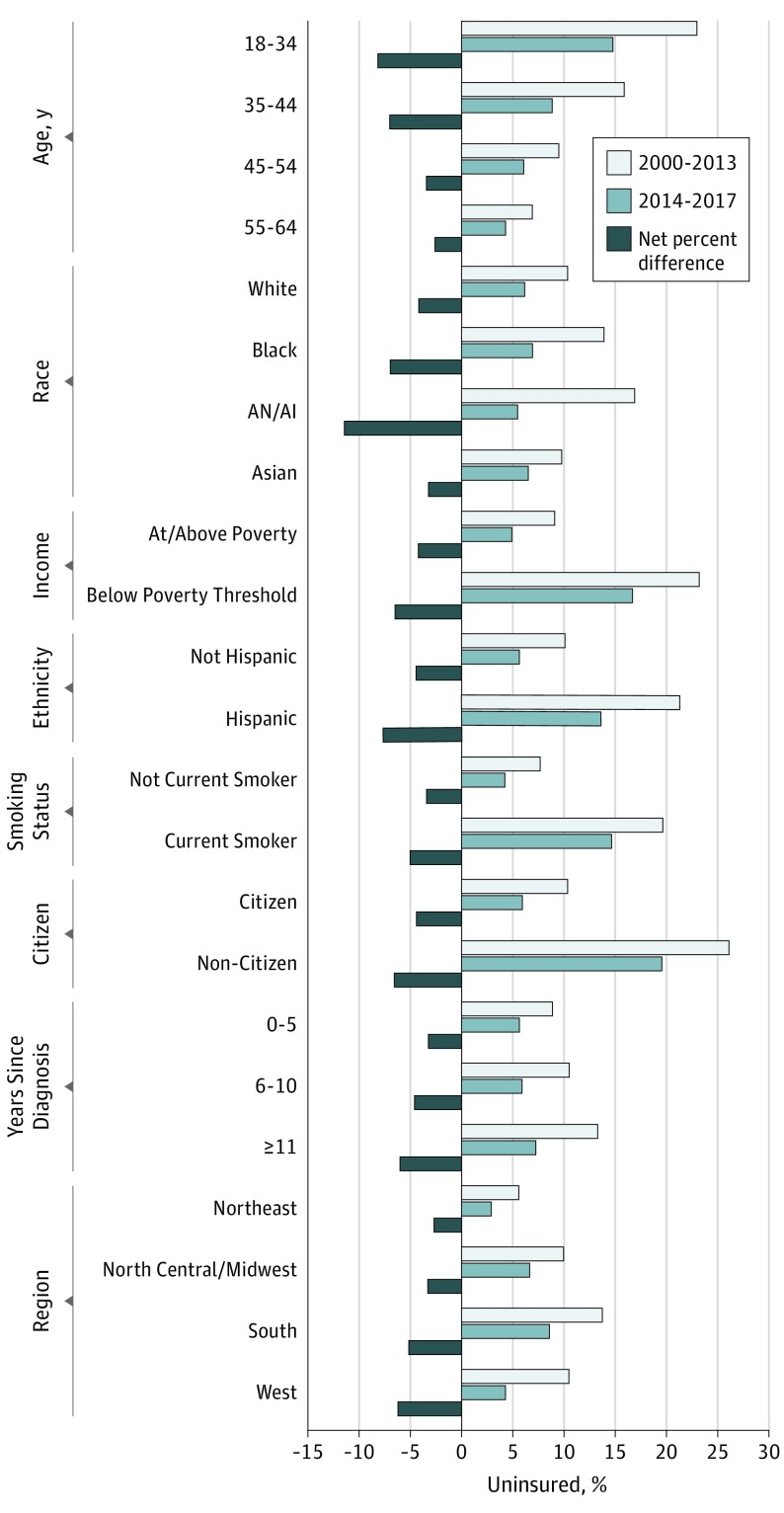

Compared with the 2000-2013 period, rates of noninsured status among cancer survivors in the 2014-2017 period decreased across all patient characteristics examined (Figure 2). Absolute coverage gains were particularly large among subpopulations targeted by the ACA, including young adults aged 18 to 34 years (+8.2%), blacks (+7.0%), Alaskan Natives and American Indians (+11.4%), individuals below the poverty threshold (+6.5%), Hispanics (+7.7%), and noncitizens (+6.6%). Specifically, the uninsured rate among young adults decreased from 23.0% to 14.8%, representing a 36% decline (P < .001), and the percentage of patients below the poverty threshold without insurance decreased from 23.2% to 16.7%, representing a 28% decline (P < .001). Notably, when stratified by interval since cancer diagnosis, survivors diagnosed 11 or more years prior to survey administration also experienced the greatest coverage gains (+6.0%) with uninsured rates decreasing from 13.3% to 7.3%, representing a 45% decline (P < .001).

Figure 2. Absolute and Percentage Point Change in Uninsured Rate by Sociodemographic Characteristics Among Cancer Survivors, 2000-2013 vs 2014-2017.

Compared with the 2000-2013 period, a greater proportion of cancer survivors in the 2014-2017 period reported having Medicaid coverage (14.0% vs 8.9%, P < .001), while the rates of other insurance types did not significantly change (eFigure in the Supplement).

As detailed in Table 3, in the 2000-2013 period, younger age, black race, annual family income below the poverty threshold, Hispanic ethnicity, current smoking, noncitizen status, increasing interval from cancer diagnosis and non-Northeast region of residence were all associated with higher odds of not having insurance (P < .001 for all, with the exception of black race, P = .02). In contrast, in the 2014-2017 period, increasing interval from cancer diagnosis and Western US regions were no longer associated with higher odds of being uninsured. Notably, there were no longer racial disparities in odds of not having insurance in the 2014-2017 period (Table 3). Throughout the entire study period being a current smoker was associated with higher odds of not having insurance (P < .001) (Table 3).

Among individuals aged 18 to 26 years (n = 626), those surveyed between 2011 and 2017 had lower absolute rates of noninsured status than those in the 2000-2010 period, but the aOR was not statistically significant (19.8% vs 24.4%; aOR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.55-1.47; P = .67). The absolute percentage of participants with noninsured status among this subgroup progressively decreased over subsequent years (eTable in the Supplement) such that for those surveyed during the 2013-2017 period, rates of noninsured status were significantly lower than those surveyed in years prior (13.9% vs 25.1%; aOR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.26-0.95; P = .04). For patients diagnosed 2 years or less prior to survey administration, rates of noninsured status before and after implementation of the ACA were 8.5% vs 5.0% (aOR before vs after the ACA, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.43-0.87; P = .01). For those diagnosed more than 2 years prior to survey administration, the corresponding rates were 11.4% vs 6.6% (aOR before vs after the ACA, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.69; P < .001).

Discussion

In this comprehensive population-based study, the percentage of nonelderly cancer survivors without insurance decreased from 10.6% to 6.2% after implementation of the ACA. Coverage gains were particularly large among subpopulations targeted by the ACA, including young adults aged 18 to 34 years and individuals below the poverty threshold. The most commonly cited reason for not having insurance was cost, followed by unemployment.

In characterizing the uninsured cancer survivor population including reasons for not having insurance in the United States, our study has several important implications. First, to our knowledge, this study is the first to examine self-reported reasons for not having insurance in the oncology population. Although cost was the most commonly cited explanation, consistent with what has been shown in other studies,24,25,26 nearly the same proportion of survey participants reported employment (either unemployment or employment-related issues) as their reason for not having insurance. Future efforts to improve insurance coverage among this population will require diverse policy initiatives. Second, our findings provide further updated evidence that after implementation of the ACA, the proportion of cancer survivors lacking health insurance has decreased significantly and that this benefit was seen across all patient subgroups, including those specifically targeted by the ACA, including racial and ethnic minorities.27 Given the uncertainty of the future of the ACA, particularly regarding coverage of preexisting medical conditions including cancer diagnoses,28,29,30 assessments of the effect of this historic legislation are timely and necessary. Third, despite these improvements, our study identified several demographic subgroups who appear to continue to be at risk for not having insurance even after the ACA, which may contribute to worse cancer-specific outcomes, decreased quality of life, and greater mortality. Policymakers should be aware of these disparities when proposing legislation to either augment or limit health care coverage.

The independent association between being a current smoker and not having insurance among cancer survivors is concerning. In an attempt to account for potential excess health care costs incurred by the smoking population and to encourage tobacco cessation, the ACA allowed insurance plans to impose a surcharge on premiums for tobacco users.31 Recent studies have shown that this initiative has not decreased rates of smoking in the general population,32,33 and the present study suggests that these policies may lead to high rates of not having insurance among cancer survivors who continue to smoke. Continued smoking after a cancer diagnosis is associated with a wide range of adverse outcomes.34,35 Therefore, these individuals may stand to benefit the most from ongoing health management, so individual states should carefully consider the potential consequences of increasing insurance premiums for current smokers when deciding whether to pass tobacco surcharges.

Survivors greater than 10 years out from cancer diagnosis had greater odds of not having insurance prior to implementation of the ACA, but not after. Although these long-term survivors may be considered “cured” of their primary cancer, they remain at risk for late effects from treatment and have at least a similar risk of common comorbid conditions compared with the general population, if not higher.36,37,38,39 Our findings suggest that the provisions of the ACA targeted toward individuals with preexisting conditions were successful in increasing coverage of long-term cancer survivors. These results should be taken into consideration as current policymakers seek to actively limit health care coverage in patients with preexisting conditions.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the database did not include participants’ state of residence. We were able to capture geographic region of residence but could not formally assess the effect of state-specific Medicaid expansion programs on insurance coverage. Second, participants not having insurance were asked to choose 0 to 5 specified reasons or other as reasons for being uninsured and were not asked to elaborate on reasons if they did not fit into one of the categories provided. Therefore, reasons for not having insurance were not completely captured among all study participants. Third, given that ACA implementation was associated with an increase in overall cancer diagnoses,40 our baseline study populations before and after the ACA may be different. Fourth, another potential source of bias is cancer survivorship because individuals with insurance may have been more likely to receive treatment and survive their cancer and thus could be overrepresented in the study cohort. However, our sensitivity analyses including only patients diagnosed 2 years or less prior to survey administration showed similar increases in coverage after ACA implementation, suggesting the presence of increased coverage among individuals most likely to be undergoing active treatment.

Conclusions

In summary, cancer survivors appeared to have experienced significant improvements in insurance coverage after implementation of the ACA, although certain subgroups remained at greater risk for not having insurance. The most commonly reported reason for not having insurance was cost, although a similar proportion of cancer survivors cited employment-related issues. Our findings are important as the debate over health care reform continues, including initiatives to potentially roll back ACA coverage. Specifically, our study suggests that any future policy changes that could limit protection of individuals with preexisting conditions or decrease funding to Medicaid could be particularly detrimental to cancer survivors. Clinicians caring for patients at greatest risk for not having insurance should refer these individuals to additional services that may be able to assist them in obtaining affordable coverage. Given the growing number of cancer survivors in conjunction with rising health costs, future efforts should aim to assess the long-term consequences of not having insurance such that appropriate interventions can be delivered to increase health care access and ultimately improve cancer survivorship care.

eFigure. Self-reported insurance type among cancer survivors in the United States in 2000-2013 vs 2014-2017

eTable. Multivariable adjusted odds for not having insurance among 626 participants aged 18-26 reporting a cancer diagnosis from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in 2000-2017

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute Cancer Statistics. Updated April 27, 2018. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics. Accessed August 3, 2018.

- 2.Friedman DL, Whitton J, Leisenring W, et al. . Subsequent neoplasms in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(14):-. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(1):82-91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.M82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(1):61-70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirchhoff AC, Kuhlthau K, Pajolek H, et al. . Employer-sponsored health insurance coverage limitations: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(2):377-383. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1523-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, Alley LG, Pollack LA. Health insurance coverage and cost barriers to needed medical care among U.S. adult cancer survivors age<65 years. Cancer. 2006;106(11):2466-2475. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Aziz NM. Forgoing medical care because of cost: assessing disparities in healthcare access among cancer survivors living in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3493-3504. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis L, Canchola AJ, Spiegel D, Ladabaum U, Haile R, Gomez SL. Trends in cancer survival by health insurance status in California from 1997 to 2014. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):317-323. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu CD, Wang X, Habif DV Jr, Ma CX, Johnson KJ. Breast cancer stage variation and survival in association with insurance status and sociodemographic factors in US women 18 to 64 years old. Cancer. 2017;123(16):3125-3131. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwok J, Langevin SM, Argiris A, Grandis JR, Gooding WE, Taioli E. The impact of health insurance status on the survival of patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2010;116(2):476-485. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, Zafar SY, Ayanian JZ, Schrag D. Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1732-1740. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. . Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):980-986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker GV, Grant SR, Guadagnolo BA, et al. . Disparities in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival in nonelderly adult patients with cancer according to insurance status. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(28):3118-3125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.6258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obama B. United States health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA. 2016;316(5):525-532. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.9797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw FE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, Rein AS. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: opportunities for prevention and public health. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):75-82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60259-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaiser Family Foundation Key facts about the uninsured population: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Fact-Sheet-Key-Facts-about-the-Uninsured-Population. Accessed December 1, 2018.

- 17.Cannon RB, Shepherd HM, McCrary H, et al. . Association of the patient protection and affordable care act with insurance coverage for head and neck cancer in the SEER database. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(11):1052-1057. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nipp RD, Shui AM, Perez GK, et al. . Patterns in health care access and affordability among cancer survivors during implementation of the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(6):791-797. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soni A, Sabik LM, Simon K, Sommers BD. Changes in insurance coverage among cancer patients under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(1):122-124. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Health Interview Survey: Methods. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/methods.htm. Accessed July 1, 2018.

- 21.Blewett LA, Rivera Drew JA, Griffin R. IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 6.3 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS; 2018. doi: 10.18128/D070.V6.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzales F, Zheng Z, Yabroff KR. Trends in financial access to prescription drugs among cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(2). doi: 10.1093/jnci/djx164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, Davis WW, Brown ML. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(17):1322-1330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narang AK, Nicholas LH. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(6):757-765. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al. . Financial burden in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3474-3481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.7066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al. . Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119(20):3710-3717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchmueller TC, Levinson ZM, Levy HG, Wolfe BL. Effect of the Affordable Care Act on racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(8):1416-1421. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rovner J; National Public Radio 5 ways nixing the Affordable Care Act could upend U.S. health system. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/12/20/678395984/5-ways-nixing-the-affordable-care-act-could-upend-the-entire-u-s-health-system. Accessed December 20, 2018.

- 29.Glied S, Jackson A. Access to coverage and care for people with preexisting conditions: how has it changed under the ACA? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2017;18:1-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glied SA, Jackson A. How would Americans’ out-of-pocket costs change if insurance plans were allowed to exclude coverage for preexisting conditions? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2018;2018:1-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Overview: Final Rule for Health Insurance Market Reforms; 2013. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Files/Downloads/market-rules-technical-summary-2-27-2013.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 32.Friedman AS, Schpero WL, Busch SH. Evidence suggests that the ACA’s tobacco surcharges reduced insurance take-up and did not increase smoking cessation. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1176-1183. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan CM, Graetz I, Waters TM. Most exchange plans charge lower tobacco surcharges than allowed, but many tobacco users lack affordable coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1466-1473. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Campagna EJ, Henderson WG, Singh JA, Houston T. Adverse effects of smoking on postoperative outcomes in cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(5):1430-1438. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2128-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leach CR, Weaver KE, Aziz NM, et al. . The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):239-251. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0403-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jørgensen TL, Hallas J, Friis S, Herrstedt J. Comorbidity in elderly cancer patients in relation to overall and cancer-specific mortality. Br J Cancer. 2012;106(7):1353-1360. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mitchell AJ, Ferguson DW, Gill J, Paul J, Symonds P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(8):721-732. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70244-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prasad PK, Hardy KK, Zhang N, et al. . Psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes in adult survivors of adolescent and early young adult cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2545-2552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.7528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soni A, Simon K, Cawley J, Sabik L. Effect of Medicaid expansions of 2014 on overall and early-stage cancer diagnoses. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):216-218. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Self-reported insurance type among cancer survivors in the United States in 2000-2013 vs 2014-2017

eTable. Multivariable adjusted odds for not having insurance among 626 participants aged 18-26 reporting a cancer diagnosis from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in 2000-2017