This cohort study evaluates the association between singing in a children’s choir and the development of pediatric voice disorders.

Key Points

Question

Is there an association between singing in a children's choir and the development of pediatric voice disorders?

Findings

In this cohort study of 752 singing and 743 nonsinging children from Spain, participating in a choir was associated with lower odds of developing a voice disorder, a statistically significant finding. Voice disorders were significantly more common in the nonsinging group of children (32.4%) than in the singing group (15.6%).

Meaning

Singing in a children’s choir may be beneficial to voice health, possibly because of voice training; therefore, it may be important to introduce the same solicitude for voice in nonsinging children.

Abstract

Importance

Pediatric vocal fold pathology is important because having a healthy voice free from disorders is crucial in a child's emotional and educational development.

Objective

To determine whether there is an association between singing in a children's choir and the development of voice disorders.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Prospective cohort study of children (aged 8 to 14 years) singers selected from local children’s choirs and nonsingers selected from local schools evaluated at Clarós Otorhinolaryngology Clinic in Barcelona, Spain, from October 2016 through April 2018.

Exposures

Singing for a mean time of 7.5 hours per week for 2.5 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome of the study was the prevalence of voice disorders measured using videostroboscopy. The obtained values were analyzed statistically and used to compare the characteristics of the children and the frequency of voice disorders between the groups.

Results

Of 1495 enrolled children (745 male [49.8%]; median age, 9.3 years [range, 8-14 years]), 752 were singers and 743 were nonsingers. No differences in baseline characteristics were observed between the groups. Voice disorders were more frequent in the nonsinging group than in the singing group (32.4% vs 15.6%; difference, 16.8%; 95% CI, 12.3%-21.4%). Of 12 voice disorders considered in this study, all 12 were more frequent in the nonsinging group. Functional voice disorders were more frequent in the nonsinging group than in the singing group (20.2% vs 9.4%; difference, 10.8%; 95% CI, 7.2%-14.3%), as were organic voice disorders (12.2% vs 6.1%; difference, 6.1%; 95% CI, 2.6%-9.6%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Voice disorders were less common among children in the cohort who sing in choirs, possibly because of voice training and the commonly observed habit of attending regular ear, nose, and throat examination. Voice disorders may be prevented in nonsinging children if the same solicitude for voice is observed.

Introduction

The importance of a voice free from disorders in the educational, emotional, and behavioral development of a child is difficult to overestimate.1,2 The positive association of singing with well-being is also widely supported by research.3,4,5 Although the topic of the voice of choir singers has received a reasonable amount of attention in the literature, children singing in choirs, especially from the prepubescent group, have not been evaluated fully. In particular, vocal fold pathologic findings in this group and the possible association with choir singing has, to our knowledge, yet to be explored fully. This cohort addressed this gap by evaluating the odds of the diagnosis of voice disorders in singing and nonsinging children. Our primary hypothesis was that singing in choir is protective against developing voice disorders.

Methods

Study Population

Children aged 8 to 14 years were included in the research. The age of 8 years was chosen as the lower limit because children younger than 8 years have difficulty cooperating with the examination, which could lead to inaccurate results; 14 years was chosen as the upper age limit because of possible pubertal changes in older children. Parents were asked to strictly confirm prepubertal age for boys and premenarchal age with no sign of breast growth for girls. Exclusion criteria included (1) history of neck trauma, (2) previous intubations or laryngeal, head and neck, or torso surgical procedures that have caused voice disorders, (3) use of medications that might affect voice (eg, antihistamines, steroids, or diuretics), and (4) current sickness or seasonal allergies. Participants included in the initial study were selected from 7 choirs and 4 schools in Spain. Using a simple randomization method, children meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria were randomly selected to participate in the study. The study started on October 5, 2016, and finished on April 10, 2018. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Clarós Otorhinolaryngology Clinic institutional review board, Barcelona, Spain. All parents of participants were informed about the examination technique and provided written informed consent before the child was added to the study.

Survey Administration

We developed a specially constructed survey (eAppendix in the Supplement) that was adapted from widely recognized questionnaires such as the Pediatric Voice Handicap Index (pVHI), the Pediatric Voice Outcomes Survey (PVOS), and the Pediatric Voice-Related Quality of Life Survey (PV-RQOL).6,7,8 All 3 questionnaires were used because each contributes important variables: the pVHI includes a question about a child talkativeness and voice complaints, such as voice sounding raspy, dry and hoarse; the PV-RQOL, a question about poor strength of the voice; and the PVOS, a question about voice strain while speaking. When asking about voice disorder symptoms, we also clarified that it may mean problems in speaking and being understood in a noisy area, running out of air and being forced to take frequent breaths while talking, having trouble using the telephone or speaking with friends in person, and being forced to repeat oneself (based on the PV-RQOL) or problems in hearing the child’s voice when he or she is calling through the house, voice changes throughout the day, and a worse voice in the evening (based on the pVHI).

First, the survey was given to the participants’ parents, choir conductors (for singing children), and school teachers (for nonsinging children) to give them a chance to get familiar with the questions and focus on symptoms of which they might have been previously unaware. Three weeks later, the choir conductors and school teachers scheduled meetings (after school classes or singing lessons) with the parents of each child separately to complete the survey together. The survey included questions about the child's characteristics (age and sex), biometric data (body mass index to determine whether a child was underweight, at a healthy weight, or overweight), levels of different attributes (nervousness, talkativeness, and tearfulness), hobbies (eg, involvement in sport), and pertinent medical history (eg, reflux symptoms). Parents were also surveyed regarding whether their child had any voice disorder symptoms (eg, singing effort, poor strength of the voice, hoarseness, or vocal strain).

Perceptual Analysis

The GRBAS scale9 was completed, which gives scores from 0 to 3 for hoarseness (dysphonia grade), roughness, breathiness, asthenia, and vocal strain.10 Because parents, choir conductors, and school teachers would likely not be familiar with the GRBAS scale, we ensured that they understood the scale adequately through training and precise instructions. During the training, 2 speech pathologists (A.C.-P. and C.P.) explained the terms used in the GRBAS scale and provided special recordings presenting the examples of rough voice, hoarse voice, breathiness, asthenia, and vocal strain. Then the speech pathologists, together with parents and the choir conductors or school teachers, completed the GRBAS scale.

Instrumental Voice Analysis

The ear, nose, and throat consultant (P.C. or A.C.) performed a videolaryngoscopy followed by a videostroboscopy (Hopkins II telescope 70 degrees; Karl Storz) for all patients. The investigations were performed while the children were awake. During the examinations, the consultants evaluated the motion and phase symmetry of the vocal folds, the presence of any vocal fold irregularities, mucosal structure and any mucosal abnormalities, the presence of edema or secretion, glottal closure, supraglottic compression or compensation, mucosal wave abnormalities, mucous build-up, and the position and movement of the arytenoids. We used a rigid endoscope because it produces better image quality than a flexible one. However, we used a flexible endoscope in several cases in which we were having difficulty cooperating with a child during examination, because a flexible endoscope does not pull a child's tongue in the same way as a rigid endoscope. All children tolerated the examination well.

Functional voice disorders were defined as a disproportion between the laryngeal and perilaryngeal muscular activity11,12 and were diagnosed based on the symptoms (harsh strained voice of increased effort, decreased volume and unsettled pitch interspersed with periods of normal voice, poor voice control, odynophonia, tenderness in the thyrohyoid space, and tension in neck and shoulders)12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 and examination findings ruling out structural or neurological vocal fold pathologic features.20 Among disorders without organic lesions, we distinguished12 psychological dysphonia (if the potential cause was psychological, based on parent, teacher, and choir conductor reports)21 and muscle tension dysphonia (MTD) (all other situations, excluding puberphonia, which was discounted from the study).

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of our study was the number of voice disorders diagnosed using videolaryngoscopy and videostroboscopy, and the secondary outcomes were the voice symptoms reported in the survey and those measured with the GRBAS scale. We calculated the sample size necessary for finding a significant difference in the prevalence of voice disorders between singing and nonsinging children. For this calculation, we assessed the power of the test equal to 80% as a standard for adequacy because this convention implies a 4 to 1 trade-off between β risk (probability of a type II error) and α risk (probability of a type I error); with .2 and .05 as conventional values for β and α. The smallest sample size of the study and control group was calculated to be a minimum of 131 participants.

Data were implemented into Statistica software, version 13.1 (StatSoft). To examine whether singing in a children’s choir is protective against developing voice disorders, χ2 tests were performed to compare differences between the children's characteristics and the prevalence of voice disorders in both groups and determine whether the differences were statistically relevant. Statistical significance was reported as 1-sided α = .05. To counteract the problem of multiple comparisons, we adjusted our calculations using the Bonferroni correction, obtaining a new confidence level. The effect size was reported using a φ coefficient, and a CI was established for each obtained value. Confidence intervals were interpreted to determine whether the results were consistent with a clinically meaningful difference.

Results

Of 1495 children aged 8 to 14 years examined in this study, 745 [49.8%] were male, with mean (SD) age of 12 (1.3) years. In all, we examined 752 choristers and 743 nonsinging children. There was no difference in distribution of sex, age, and body mass index percentile between groups (Table 1). The presence of reflux symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, and dyspepsia not confirmed by any examination) was higher among nonsinging than singing children (10.8% vs 6.4%; difference, 4.4%; 95% CI, 1.6%-7.3%), and the prevalence of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (presumed based on laryngeal examination and pH test) was higher among singing children than nonsinging children (5.2% vs 3.8%; difference, 1.4%; 95% CI, 0%-3.6%). Participation in team sport classes was higher among singing children (82.4% vs 74.3%; difference, 8.2%; 95% CI, 4.0%-12.3%). No other characteristics measured differed between groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Singing and Nonsinging Children.

| Characteristic | Children Group, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Singing (n = 752) | Nonsinging (n = 743) | |

| Female | 394 (52.4) | 356 (47.9) |

| Age, y | ||

| 8-10 | 194 (25.8) | 189 (25.4) |

| 11-12 | 414 (55.1) | 402 (54.1) |

| 13-14 | 144 (19.1) | 152 (20.5) |

| Body mass indexa | ||

| Underweight, <5th percentile | 113 (15.0) | 128 (17.2) |

| Healthy weight, 5th to 85th percentile | 566 (75.3) | 533 (71.7) |

| Overweight, ≥85th percentile | 73 (9.7) | 82 (11.0) |

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Voice Disorders

In all, 358 of 1495 children (23.9%; 95% CI, 21.6%-26.2%) involved in our study had a voice disorder. The most common voice disorders were MTD (191 [12.8%; 95% CI, 11.1%-14.5%]) and vocal fold nodules (89 [6.0%; 95% CI, 4.7%-7.1%]). The prevalence of dysphonia in our study was 11.2% (95% CI, 9.6%-12.8%, n = 168). The prevalence of all functional disorders was 14.8% (95% CI, 13.0%-16.6%; n = 221), and the prevalence of all organic pathologies in our study was 9.2% (95% CI, 7.5%-11.0%; n = 137).

Voice disorders were more common in the group of nonsinging children than in singing children (32.4% vs 15.6%; difference, 16.8%; 95% CI, 12.3%-21.4%). In the group of all children with voice disorders examined in our study, 241 (67.3%; 95% CI, 62.5%-72.2%) were nonsinging.

Twelve different voice disorders were identified across study groups (Table 2). All pathologies were more common in the nonsinging group. The biggest differences between the nonsinging and singing groups were as follows: MTD (17.2% vs 8.4%; difference, 8.8%; 95% CI, 6.0%-11.7%), psychogenic dysphonia (3.0% vs 1.1%; difference, 1.9%; 95% CI, 0.5%-3.5%), and vocal fold nodules (7.9% vs 4.0%; 95% CI, 1.6%-6.4%).

Table 2. Prevalence of Voice Disorders Among the Singing and Nonsinging Children.

| Voice Disorder | Children Group, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Singing (n = 752) | Nonsinging (n = 743) | |

| All voice disorders | 117 (15.6) | 241 (32.4) |

| All functional pathologic findings | 71 (9.4) | 150 (20.2) |

| All organic pathologic findings | 46 (6.1) | 91 (12.2) |

| Muscle tension dysphonia | 63 (8.4) | 128 (17.2) |

| Psychogenic dysphonia | 8 (1.1) | 22 (3.0) |

| Vocal nodules | 30 (4.0) | 59 (7.9) |

| Cysts | 5 (0.7) | 12 (1.6) |

| Congenital cysts | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.7) |

| Polyps | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) |

| Sulcus vocalis | 4 (0.5) | 6 (0.8) |

| Sulcus vergeture | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) |

| Laryngeal web | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) |

Functional voice disorders were more common in the nonsinging group (20.2% vs 9.4%; difference, 10.8%; 95% CI, 7.2%-14.3%). Similarly, organic voice disorders were more frequent in the nonsinging group (12.2% vs 6.1%; difference, 6.1%; 95% CI, 2.6%-9.6%).

Secondary Outcomes

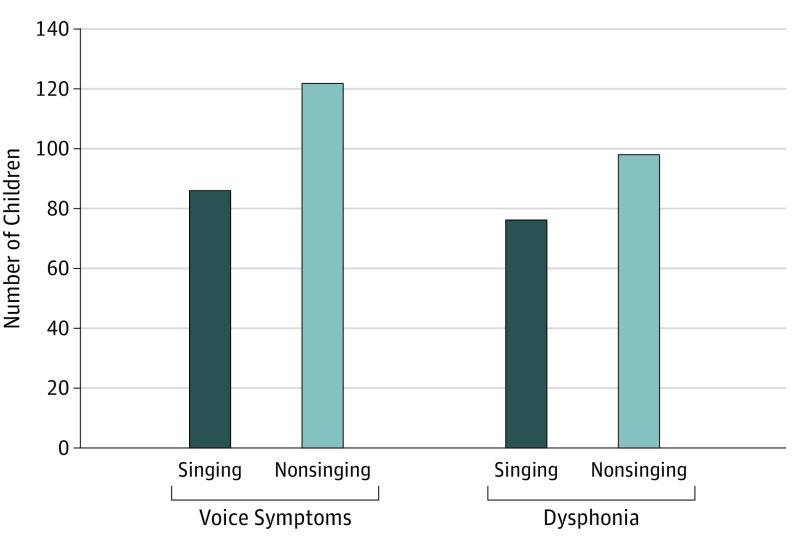

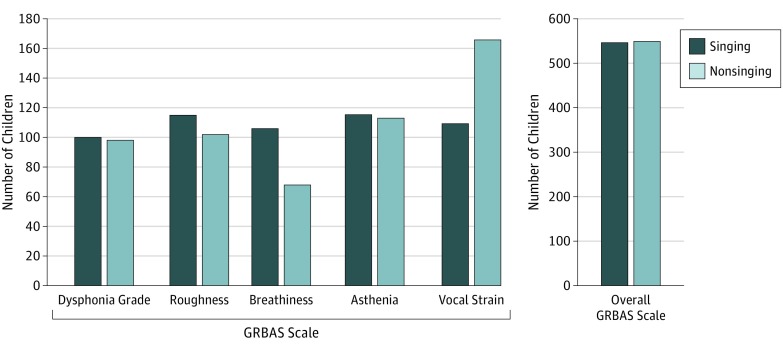

In all, 373 participants (24.9% [95% CI, 22.8%-27.1%]) involved in our study had dysphonia or other voice complaints. The prevalence of dysphonia-related symptoms reported by children, parents, teachers, and choir directors was higher in the nonsinging group than in the singing group (28.9% vs 21.0%; difference, 7.9%; 95% CI, 3.5%-12.3%) (Figure 1). Total GRBAS scores were similar between groups (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Presence of Dysphonia and Other Voice Symptoms in the Singing and Nonsinging Children.

Figure 2. Comparison of the GRBAS Scale Evaluation Between the Singing and Nonsinging Groups.

GRBAS scale indicates dysphonia grade, roughness, breathiness, asthenia, and vocal strain.

Discussion

The results of our research suggest that voice disorders are more common in nonsinging children than in choristers. According to our review of the literature, other research had not reported this finding.22,23 In fact, the opposite result was suspected because of the perceived negative association of singing and vocal abuse with the health of vocal fold tissue24,25,26; this was supported in the previous literature.27 The positive association of singing with voice health and development has been described by some authors but only through the beneficial psychological influence on the treated patient.28,29 In agreement with our findings, in one study, singing was associated with less likelihood of having severe dysphonia; however, that study did not diagnose specific voice disorders.30 One study reported the low representation of choristers among children with voice disorders (0.2%); however, singing was associated with higher likelihood of having vocal fold nodules,31 a finding that contradicts our results.

Our results were not surprising to our research team. The Clarós Otorhinolaryngology Clinic has been a widely known consultancy for professional opera singers of the Gran Teatro del Liceo in Barcelona since 1970. The clinic has also provided medical support for a large number of children from choirs for many years. During this period, we noticed a conscious approach to the importance of regular laryngologic control from both singers’ parents and choir conductors, who tend to be vigilant about sending a child to a specialist as soon as they notice a disorder in the singing voice. Furthermore, Spanish choirs are characterized by a high level of attention toward teaching choristers to use the voice properly, including collaborating with speech therapists. Children singing in choir are aware from their youngest years of how to use their voices without causing voice trauma, and they are taught voice exercises that they should perform regularly. Nonsinging children are not subject to the same level of monitoring or given this type of training and are exposed to voice trauma during everyday situations (eg, shouting during team sports or playing with their siblings and friends). Many published articles agree that proper voice training can result in better voice use.23,26,32 We believe that the lack of access of the nonsinging group to screening or voice training may be the reason that vocal fold nodules were as much as 2 times more frequent in this group despite vocal fold nodules being known to be caused by voice misuse and vocal trauma.8,11,33,34 Thus, vocal fold nodules should be more frequent in the group of children who are potentially overusing their voice through frequent singing (ie, presumably in the group of singers).

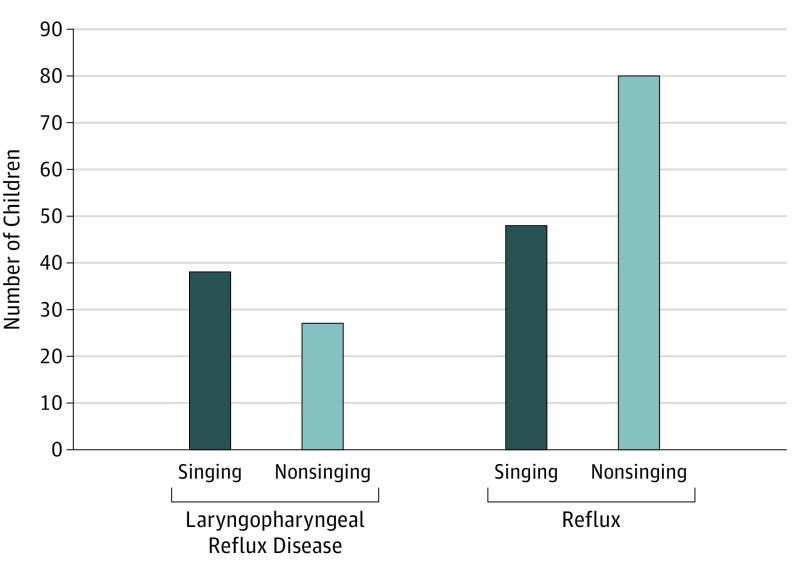

To further support this explanation, in our research, reflux as a symptom (subjective reports of reflux-related symptoms such as heartburn, regurgitation, and dyspepsia, documented in the survey and not supported by an examination) was more frequent in the nonsinging group, whereas laryngopharyngeal reflux disease (diagnosed by a physician after laryngeal examination and pH test) was more frequent in the group of children singing in the choir (Figure 3). This result showed that choristers were more frequently examined and attended regular checkups with the otorhinolaryngologist. Results of the GRBAS scale evaluation also reflected the greater awareness among the singing group of the importance of voice care (Figure 2).

Figure 3. Presence of Reflux and Diagnosed Laryngopharyngeal Reflux Disease in the Singing and Nonsinging Children.

Despite the higher frequency of voice disorders and subjective symptoms noted among the nonsinging group, the total score of the GRBAS scale was almost the same in both groups. This result suggests that despite the singing children presenting with less frequent vocal fold pathologic findings and voice symptoms than the nonsinging group, the children (and their parents and teachers) cared more about their voices and paid more attention to the presence of hoarseness, roughness, breathiness, and asthenia. They were also likely to be more familiar with the implications of those symptoms and therefore more capable of evaluating the scale meaningfully. A different explanation may be that children who become choir members necessarily require a beautiful singing voice. This initial selection may have been the first screening for vocal fold disorders. Thus, the prevalence of vocal fold disorders in beginner singers in choir was likely to be low. The lack of difference between the groups in the total GRBAS scale might be because the children were evaluated by persons who had a personal relationship with the child and by speech pathologists, and not by an independent speech language pathologist alone, which could lead to bias.

Our finding that 23.9% of the children presented with voice disorders was high in comparison with the other studies, which gave a range of 1.2 to 23.9%.31,35,36,37,38 The lack of consistency across different studies in diagnoses, study group characteristics, or definitions of voice disorders might explain the wide ranges (6% to 38%) reported in some studies.11,39,40 The prevalence of dysphonia in our study was 11.2%, which varied significantly with the results of Carding et al (6%)39 and Bonet and Casan (20.2%)41 but corresponded well with the results of Tavares et al (11.4%).25 In our research, the most frequent pathologic finding of the vocal folds was MTD (prevalence of 12.8%). The second most frequent pathologic finding was vocal fold nodules, which manifested in a relatively low frequency of 6.0%. This result is different from most findings by other researchers, who found nodules to be the most frequent finding and reported the prevalence of nodules to be between 16.9% and 30.2%32 and from 52% to 86% among children with voice problems.2,8,42,43 Furthermore, Smillie et al2 found the prevalence of MTD to be as low as 9% among the laryngologic school-aged patients—a significant contrast with our calculations, which showed high prevalence of MTD. The same large difference between our results and the results of other authors may be seen in the frequency of the functional pathologic findings. A total prevalence of 14.8% for all functional voice disorders was reported in our study compared with the low prevalence of 4% to 7% among children with dysphonia reported by Smith.11 The organic pathologic findings in our study were less frequent (prevalence of 9.2%), which was in opposition to a higher prevalence reported by the literature.2,12,44,45

Among functional voice disorders, we distinguished psychological dysphonia (if the potential cause was psychological)21 and we discounted psychological dysphonia from MTD. This distinction was based on reports by parents, teachers, and choir conductors and not on psychiatric or psychological examination; therefore, psychogenic dysphonia should not be treated as a definite diagnosis. Our research showed analyses of prevalence of MTD and psychological dysphonia both separately and together in the group of functional voice disorders.

Limitations

It is important to point out the limitations of this study. First, with all research involving children, there was uncertainty whether the patient understood our instructions adequately, which could have influenced the results.40 Second, it has become well accepted that in studies involving parents' or teachers' responses, the clarity of results is not fully ensured. One reason being that the parents and teachers, who are familiar with a child's voice, may evaluate dysphonia differently than the physician or may even not notice it.11,14 Another reason is that the replies and understanding of respondents with regard to the questions may vary.12 Finally, parents and teachers may have responded differently compared with young patients themselves8 despite the fact that a good association between the children's and parents' responses was reported.46 Although we checked several risk factors associated with the vocal cords, there were still many that may potentially cause voice trauma. One risk factor would be playing a wind instrument, which is typically very popular in the group of singing children23; other potential factors are the specific socioeconomic environment,2,47,48 emotional problems and conflicts at home,35 or being raised in a big family with many siblings.11,39,49

Conclusions

The findings suggest that there is a negative association between singing in a children's choir and the presence of voice disorders. The importance of voice care is particularly salient in children because they do not control their behavior or voice as well as adults and therefore are more vulnerable to possible voice trauma. In turn, voice care can influence the long-term personal and professional lives of individuals. Thus, introduction to professional voice care to children's choirs, including strict collaboration with speech therapists, specific education of parents and children, evaluating children's voices regularly, and frequent otorhinolaryngologic examination, may be an important intervention. We believe that it is crucial to introduce the same solicitude for voice in nonsinging children.

eAppendix. Survey NR.

References:

- 1.Connor NP, Cohen SB, Theis SM, Thibeault SL, Heatley DG, Bless DM. Attitudes of children with dysphonia. J Voice. 2008;22(2):197-209. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smillie I, McManus K, Cohen W, Lawson E, Wynne DM. The paediatric voice clinic. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(10):912-915. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins FS, Fleming R. Sound Health: an NIH-Kennedy Center initiative to explore music and the mind. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2470-2471. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marwick C. Leaving concert hall for clinic, therapists now test music’s “charms”. JAMA. 1996;275(4):267-268. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530280017006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bieleninik L, Geretsegger M, Mössler K, et al. ; TIME-A Study Team . Effects of improvisational music therapy vs enhanced standard care on symptom severity among children with autism spectrum disorder: the TIME-A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(6):525-535. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.9478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerschner JE, Merati AL. Science of voice production from infancy through adolescence In: Hartnick CJ, Boseley ME, eds. Pediatric Voice Disorders. Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Plural Publishing Inc. 2008:23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zur KB, Cotton S, Kelchner L, Baker S, Weinrich B, Lee L. Pediatric Voice Handicap Index (pVHI): a new tool for evaluating pediatric dysphonia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71(1):77-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanz L, Bau P, Arribas I, Rivera T. Adaptation and validation of Spanish version of the pediatric Voice Handicap Index (P-VHI). Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79(9):1439-1443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GRBAS scale. https://www.gpnotebook.co.uk/simplepage.cfm?ID=x20161228165732191130. Accessed February 12, 2019.

- 10.Omori K. Diagnosis of voice disorders. JMAJ. 2011;54(4):248-253. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith ME. Care of the child’s voice: a pediatric otolaryngologist’s perspective. Semin Speech Lang. 2013;34(2):63-70. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1342977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rickert MS, Zur KB. Disorders of the pediatric voice In: Wetmore RF, Muntz HR, McGill TJ, eds. Pediatric Otolaryngology: Principles and Practice Pathways. 2nd ed Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2012:687-696. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roy N, Bless DM, Heisey D. Personality and voice disorders: a multitrait-multidisorder analysis. J Voice. 2000;14(4):521-548. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(00)80009-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paolillo NP, Pantaleo G. Development and validation of the voice fatigue handicap questionnaire (VFHQ): clinical, psychometric, and psychosocial facets. J Voice. 2015;29(1):91-100. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy N, Bless DM, Heisey D, Ford CN. Manual circumlaryngeal therapy for functional dysphonia: an evaluation of short- and long-term treatment outcomes. J Voice. 1997;11(3):321-331. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(97)80011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welham NV, Maclagan MA. Vocal fatigue: current knowledge and future directions. J Voice. 2003;17(1):21-30. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(03)00033-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacheco PC, Karatayli-Ozgursoy S, Best S, Hillel A, Akst L. False vocal cord botulinum toxin injection for refractory muscle tension dysphonia: our experience with seven patients. Clin Otolaryngol. 2015;40(1):60-64. doi: 10.1111/coa.12333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watts CR, Hamilton A, Toles L, Childs L, Mau T. A randomized controlled trial of stretch-and-flow voice therapy for muscle tension dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(6):1420-1425. doi: 10.1002/lary.25155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitch JA, Oates J. The perceptual features of vocal fatigue as self-reported by a group of actors and singers. J Voice. 1994;8(3):207-214. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(05)80291-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy N. Functional dysphonia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11(3):144-148. doi: 10.1097/00020840-200306000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison MD, Rammage LA. Muscle misuse voice disorders: description and classification. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113(3):428-434. doi: 10.3109/00016489309135839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tepe ES, Deutsch ES, Sampson Q, Lawless S, Reilly JS, Sataloff RT. A pilot survey of vocal health in young singers. J Voice. 2002;16(2):244-250. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(02)00093-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fuchs M, Meuret S, Geister D, et al. Empirical criteria for establishing a classification of singing activity in children and adolescents. J Voice. 2008;22(6):649-657. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kay NJ. Vocal nodules in children—aetiology and management. J Laryngol Otol. 1982;96(8):731-736. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100093051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavares EL, Brasolotto A, Santana MF, Padovan CA, Martins RH. Epidemiological study of dysphonia in 4-12 year-old children. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;77(6):736-746. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942011000600010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Titze IR. Mechanical stress in phonation. J Voice. 1994;8(2):99-105. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(05)80302-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dejonckere PH. Voice problems in children: pathogenesis and diagnosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1999;49(suppl 1):S311-S314. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(99)00230-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamplin J, Baker FA, Jones B, Way A, Lee S. “Stroke a chord”: the effect of singing in a community choir on mood and social engagement for people living with aphasia following a stroke. NeuroRehabilitation. 2013;32(4):929-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rinta T, Welch GF. Should singing activities be included in speech and voice therapy for prepubertal children? J Voice. 2008;22(1):100-112. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams J, Welch G, Howard DM. An exploratory baseline study of boy chorister vocal behaviour and development in an intensive professional context. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2005;30(3-4):158-162. doi: 10.1080/14015430500262095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reilly JS. The “singing-acting” child: the laryngologist’s perspective—1995. J Voice. 1997;11(2):126-129. doi: 10.1016/S0892-1997(97)80066-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akif Kiliç M, Okur E, Yildirim I, Güzelsoy S. The prevalence of vocal fold nodules in school age children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68(4):409-412. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nardone HC, Recko T, Huang L, Nuss RC. A retrospective review of the progression of pediatric vocal fold nodules. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(3):233-236. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.6378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karkos PD, McCormick M. The etiology of vocal fold nodules in adults. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17(6):420-423. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328331a7f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirschberg J, Dejonckere PH, Hirano M, Mori K, Schultz-Coulon HJ, Vrticka K. Voice disorders in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;32(suppl):S109-S125. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(94)01149-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senturia BH, Wilson FB. Otorhinolaryngic findings in children with voice deviations: preliminary report. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1968;77(6):1027-1041. doi: 10.1177/000348946807700603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Powell M, Filter MD, Williams B. A longitudinal study of the prevalence of voice disorders in children from a rural school division. J Commun Disord. 1989;22(5):375-382. doi: 10.1016/0021-9924(89)90012-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duff MC, Proctor A, Yairi E. Prevalence of voice disorders in African American and European American preschoolers. J Voice. 2004;18(3):348-353. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2003.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carding PN, Roulstone S, Northstone K; ALSPAC Study Team . The prevalence of childhood dysphonia: a cross-sectional study. J Voice. 2006;20(4):623-630. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brockmann-Bauser M, Beyer D, Bohlender JE. Clinical relevance of speaking voice intensity effects on acoustic jitter and shimmer in children between 5;0 and 9;11 years. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;78(12):2121-2126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bonet M, Casan P. Evaluation of dysphonia in a children’s choir. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 1994;46(1):27-34. doi: 10.1159/000266288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shearer WM. Diagnosis and treatment of voice disorders in school children. J Speech Hear Disord. 1972;37(2):215-221. doi: 10.1044/jshd.3702.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverman EM, Zimmer CH. Incidence of chronic hoarseness among school-age children. J Speech Hear Disord. 1975;40(2):211-215. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4002.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martins RH, do Amaral HA, Tavares EL, Martins MG, Gonçalves TM, Dias NH. Voice disorders: etiology and diagnosis. J Voice. 2016;30(6):761.e1-761.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell TF, Dollaghan CA, Yaruss JS. Disorders of language, phonology, fluency, and voice in children: indicators for referral In: Bluestone CD, Stool SE, Alper CM, et al. , eds. Pediatric Otolaryngology. 4th ed Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003:1773-1787. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dejonckere PH, Wieneke GH, Bloemenkamp D, Lebacq J. Fo-perturbation and Fo/loudness dynamics in voices of normal children, with and without education in singing. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;35(2):107-115. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01291-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen W, Wynne DM. Parent and child responses to the Pediatric Voice-Related Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. J Voice. 2015;29(3):299-303. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basch CE. Aggression and violence and the achievement gap among urban minority youth. J Sch Health. 2011;81(10):619-625. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00636.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathieson L. Greene and Mathieson’s the Voice and its Disorders. 6th ed Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Survey NR.