Key Points

Question

Is operative intervention for adhesive small-bowel obstruction associated with long-term risk of recurrence?

Findings

In this propensity-matched study using population-level data of 27 904 patients, operative intervention for a patient’s first episode of adhesive small-bowel obstruction significantly reduced the probability of recurrence (13.0% vs 21.3%). The risk of additional recurrences increased with each episode until surgical intervention, at which point the risk of subsequent recurrence decreased by approximately 50%.

Meaning

The current standard for the management of adhesive small-bowel obstruction, which advocates a trial of nonoperative management, may not consider the long-term consequences of nonoperative management.

This population-based cohort study assesses the incidence of recurrence after an index episode of adhesive small-bowel obstruction to determine whether operative vs nonoperative management is associated with the risk of recurrence among patients in hospital administrative databases.

Abstract

Importance

Adhesive small-bowel obstruction (aSBO) is a potentially chronic, recurring surgical illness. Although guidelines suggest trials of nonoperative management, the long-term association of this approach with recurrence is poorly understood.

Objective

To compare the incidence of recurrence of aSBO in patients undergoing operative management at their first admission compared with nonoperative management.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This longitudinal, propensity-matched, retrospective cohort study used health administrative data for the province of Ontario, Canada, for patients treated from April 1, 2005, through March 31, 2014. The study population included adults aged 18 to 80 years who were admitted for their first episode of aSBO. Patients with nonadhesive causes of SBO were excluded. A total of 27 904 patients were included and matched 1:1 by their propensity to undergo surgery. Factors used to calculate propensity included patient age, sex, comorbidity burden, socioeconomic status, and rurality of home residence. Data were analyzed from September 10, 2017, through October 4, 2018.

Exposures

Operative vs nonoperative management for aSBO.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was the rate of recurrence of aSBO among those with operative vs nonoperative management. Time-to-event analyses were used to estimate hazard ratios of recurrence while accounting for the competing risk of death.

Results

Of 27 904 patients admitted with their first episode of aSBO, 6186 (22.2%) underwent operative management. Mean (SD) patient age was 61.2 (13.6) years, and 51.1% (14 228 of 27 904) were female. Patients undergoing operative management were younger (mean [SD] age, 60.2 [14.3] vs 61.5 [13.4] years) with fewer comorbidities (low burden, 382 [6.2%] vs 912 [4.2%]). After matching, those with operative management had a lower risk of recurrence (13.0% vs 21.3%; hazard ratio, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.56-0.68; P < .001). The 5-year probability of experiencing another recurrence increased with each episode until surgical intervention, at which point the risk of subsequent recurrence decreased by approximately 50%.

Conclusions and Relevance

According to this study, operative management of the first episode of aSBO is associated with significantly reduced risk of recurrence. Guidelines advocating trials of nonoperative management for aSBO may assume that surgery increases the risk of recurrence putatively through the formation of additional adhesions. The long-term risk of recurrence of aSBO should be considered in the management of this patient population.

Introduction

Small-bowel obstruction (SBO) is one of the most common reasons for admission to a surgical service in developed countries. Approximately 1 in 6 emergency admissions to a general surgical service can be attributed to SBO.1,2,3 In the United States, more than 350 000 operations for SBO are performed annually, resulting in more than 960 000 inpatient days and $2.3 billion in health care expenditures.4,5

Approximately 75% of SBOs are due to intra-abdominal adhesions, usually as a consequence of previous surgery.6 Adhesion formation is thought to occur after almost all abdominal operations.7,8,9 Nonoperative management of adhesive SBO (aSBO) is often successful, with 70% to 80% of patients experiencing resolution of their symptoms without operative intervention.10,11,12 Therefore, management of aSBO presents surgeons with a dilemma: Nonoperative management leaves the offending adhesion in place, whereas surgical intervention may cause new adhesions. Both management strategies leave intra-abdominal adhesions, which could result in recurrence of aSBO. Recurrence is common, occurring in approximately 20% of patients.2

Previous studies have suggested that nonoperative management of SBO may be associated with a greater risk of recurrence than operative management. However, these studies have been limited by heterogeneity of the patient cohort with respect to the causes of SBO (eg, hernia, malignant neoplasm) or by an inability to identify a patient’s first episode of aSBO.2,13,14 These limitations would affect the relevance of previously reported recurrence rates in guiding care for individual patients. To better define optimal treatment strategies among patients with aSBO, we sought to evaluate the association between operative intervention at the first admission and the risk of recurrence.

Methods

Design

This retrospective, population-based cohort study included patients who were admitted to the hospital in Ontario, Canada, for their first aSBO. This study relied on population-level administrative data collected by the Ministry of Health and Long-term Care of Ontario. The universally accessible, single-payer health care system in Ontario facilitates the capture of every health care encounter for residents of Ontario and subsequent longitudinal follow-up, permitting evaluation of long-term outcomes with minimal loss to follow-up. We compared the rate of recurrence of aSBO between patients who were treated operatively vs nonoperatively. Among those patients with recurrences, we also compared the rate of additional recurrences between patients undergoing operative vs nonoperative management during their subsequent admission. Ethical review was performed by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which waived the need for informed consent for use of these databases with coded identifiers.

Data Sources

Data were obtained from the following sources: (1) the Discharge Abstract Database, which captures reasons for admission for all acute care hospitals in Ontario; (2) the Registered Persons Database, with demographic data for persons in Ontario who are eligible for care under the Ontario Health Insurance Plan; (3) the Ontario Health Insurance Plan Claims Database of all physician-submitted procedural billing codes; and (4) the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System, which captures emergency department visits in Ontario. Data from these sources have previously been validated for a number of surgical and nonsurgical diseases.15,16,17,18,19,20 Data sets were linked using unique, encoded identifiers and analyzed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences.

Cohort

Adults aged 18 to 80 years who were admitted to the hospital from April 1, 2005, through March 31, 2014, with a primary diagnosis of adhesive intestinal obstruction (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] code K56.5) or unspecified intestinal obstruction (ICD-10 code K56.6) were included. From this initial cohort, we excluded all patients with any diagnosis codes consistent with potentially nonadhesive causes of SBO (eTable 1 in the Supplement). We used a 5-year look-back window before each patient’s entry into the cohort to exclude patients with a prior diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease as well as those who had undergone abdominal or pelvic radiotherapy. To exclude patients with a history of SBO, any patients with a diagnosis of adhesive intestinal obstruction or unspecified intestinal obstruction within 5 years of entry into the cohort were also excluded. The Discharge Abstract Database, which was used for the look-back window, began well before the necessary date to ensure adequate look-back for all patients (1988).

We elected to exclude patients older than 80 years to reduce the competing risk between recurrence and mortality. The resulting cohort consisted of adult patients 80 years or younger in Ontario admitted for their first episode of aSBO during the study period.

Exposure

The exposure in this study was operative management for aSBO. We identified operatively managed cases of aSBO using operative billing codes identified through claims data (eTable 2 in the Supplement). For the primary analysis, the study cohort was divided between those who underwent operative management for their first (index) episode of aSBO and those treated nonoperatively. For the secondary analyses, the exposure was operative management at each subsequent admission for recurrence of aSBO.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the cumulative incidence of recurrence of aSBO after the index admission. As a secondary outcome, we evaluated the incidence of additional recurrences after a patients’ second episode of aSBO. For the purposes of our analyses, we defined recurrence as an emergency admission to the hospital that met the same criteria needed to enter the cohort. To eliminate misclassification of readmissions related to a persistent episode as recurrences, we restricted our definition of recurrences to admissions for aSBO that began at least 30 days after discharge from the previous admission for aSBO.

Covariates

Patient and hospital characteristics that might confound the association between operative management and the risk of recurrence were used in propensity-score matching. Patient characteristics included age, sex, income quintile, comorbidity burden, and rurality. Income quintiles were based on census data of median income of a patient’s postal code. Comorbidity burden was calculated using the Adjusted Clinical Groups system developed by The Johns Hopkins University,21 with a 2-year look-back period that included inpatient and outpatient records. The Adjusted Clinical Groups were clustered by resource utilization bands, which categorize patients into 5 groups based on their use of health care resources. Resource utilization bands have been validated as an effective measure of comorbidity burden.22,23,24 We measured rurality using the Rurality Index of Ontario, which is calculated using population density as well as the distance to the nearest basic and advanced referral centers. We dichotomized the Rurality Index of Ontario into rural or urban as validated previously.25 Hospital characteristics included the number of beds and teaching status. We also evaluated whether patients were admitted on a weekday or a weekend.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from September 10, 2017, through October 4, 2018. We performed descriptive statistics to compare baseline characteristics of patients who underwent operative management at the index admission and those who underwent nonoperative management. We estimated the overall and 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrence for our cohort.

Propensity-Score Matching

Each patient’s propensity to undergo operative management at the index episode was estimated using a hierarchical logistic regression model that included all patient- and hospital-level covariates.26 Patients who underwent operative management were then matched 1-to-1 with those who were treated nonoperatively by propensity score using a greedy algorithm and a caliper width of 0.2 of the SD of the logit of the propensity score.27,28 Balance diagnostics were performed by calculating the standardized difference between the matched groups. A standardized difference greater than 10% was considered significant.29,30 All subsequent analyses were performed on this matched cohort.

Primary Outcome: Recurrence After the Index Episode

Using the matched cohort, we compared the cumulative incidence of recurrent aSBO between patients undergoing operative and nonoperative management. To account for the matched nature of the data, we used the McNemar tests for unadjusted analysis and reported the 2-sided P value. We estimated the relative risk reduction (RRR) associated with operative compared with nonoperative management. We performed a time-to-event analysis in the form of a Fine and Gray competing risk regression,31 which was used to model the subdistribution hazard of recurrence while accounting for the competing risk of death. In this context, a competing risk is an event that precludes a recurrent aSBO. We also evaluated whether operative factors, such as laparoscopic approach or a bowel resection, modified the association of surgery with the risk of recurrence by including the following 2 interaction terms to test for effect modification: a laparoscopic approach and bowel resection.

Secondary Outcomes: Additional Recurrences

We sought to assess the association between the operative and nonoperative management during an admission for the first and second recurrent episodes of aSBO and the incidence of subsequent episodes. For the nth recurrence, we compared the 5-year cumulative incidence of subsequent recurrence between patients undergoing operative and nonoperative management during their nth episode. We performed this analysis first on patients undergoing operative management at all previous episodes to measure the association of surgical intervention without the potential confounding that previous admissions and/or operations for aSBO might cause. We then performed the same analysis for all patients admitted for recurrent episodes, regardless of how previous episodes were managed. This analysis was performed using the McNemar test for unadjusted comparison and Fine and Grey competing risk regression to estimate the adjusted hazard ratios of additional recurrences.

Sensitivity Analysis

We performed a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded patients who underwent operative intervention for aSBO on the day of or the day after admission (postadmission days 0 and 1). These patients undergoing an early operation likely represented those with complicated aSBO, among whom a trial of nonoperative management may not have been possible.

All analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide (version 7.1; SAS Institute Inc). Results were considered statistically significant if P < .05.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Overall Incidence of Recurrence

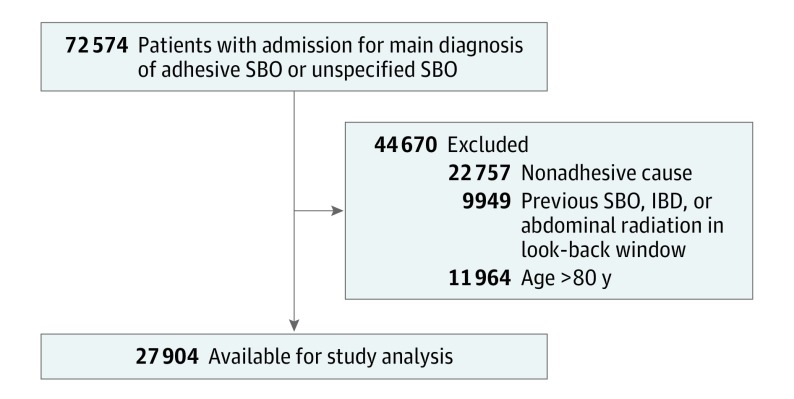

From 2005 through 2014, 27 904 patients were admitted to the hospital with their first episode of aSBO (Figure 1). The mean (SD) age of the cohort was 61.2 (13.6) years; 51.0% were women and 49.0% were men (Table). Maximum follow-up after index aSBO was 10 years. The median follow-up interval was 3.6 years (interquartile range, 1.4-6.5 years).

Figure 1. Patient Eligibility Flowchart.

IBD indicates inflammatory bowel disease; RT, radiotherapy (abdominal or pelvic); SBO, small-bowel obstruction.

Table. Baseline Characteristics of Unmatched and Matched Cohortsa.

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 27 904) | Unmatched Cohort | Matched Cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Management at Index aSBO | Standardized Difference | Management at Index aSBO | Standardized Difference | ||||

| Nonoperative (n = 21 718) | Operative (n = 6186) | Nonoperative (n = 6160) | Operative (n = 6160) | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 61.2 (13.6) | 61.5 (13.4) | 60.2 (14.3) | 0.10 | 61.1 (13.6) | 60.2 (14.3) | 0.06 |

| Female, No. (%) | 14 228 (51.0) | 10 653 (49.2) | 3575 (57.8) | 0.17 | 3656 (59.4) | 2599 (57.8) | 0.03 |

| Comorbidity burden, No. (%) | |||||||

| Healthy | 499 (1.8) | 350 (1.6) | 149 (2.4) | 0.06 | 122 (2.0) | 488 (2.4) | 0.03 |

| Low | 1294 (4.6) | 912 (4.2) | 382 (6.2) | 0.09 | 329 (5.3) | 380 (6.2) | 0.03 |

| Moderate | 9800 (35.2) | 7261 (33.5) | 2539 (41.0) | 0.16 | 2584 (42.0) | 2527 (41.0) | 0.02 |

| High | 6884 (24.7) | 5323 (24.6) | 1561 (25.2) | 0.02 | 1549 (25.2) | 1560 (25.3) | 0.02 |

| Very high | 9381 (33.7) | 7827 (36.1) | 1554 (25.1) | 0.24 | 1576 (25.6) | 1545 (25.1) | <0.01 |

| Income quintile, No. (%) | |||||||

| 1 (Lowest) | 5869 (21.1) | 4579 (21.1) | 1290 (20.9) | <0.01 | 1274 (20.7) | 1289 (20.9) | 0.01 |

| 2 | 5745 (20.6) | 4505 (20.8) | 1240 (20.1) | 0.02 | 1255 (20.4) | 1240 (20.1) | 0.01 |

| 3 | 5554 (19.9) | 4373 (20.2) | 1181 (19.1) | 0.03 | 1191 (19.3) | 1181 (19.2) | <0.01 |

| 4 | 5464 (19.6) | 4186 (19.3) | 1278 (20.7) | 0.03 | 1263 (20.5) | 1278 (20.7) | 0.01 |

| 5 (Highest) | 5092 (18.3) | 3920 (18.1) | 1172 (19.0) | 0.02 | 1177 (19.1) | 1172 (19.0) | <0.01 |

| Rural residence, No. (%) | 2211 (7.9) | 1872 (8.6) | 339 (5.5) | 0.12 | 275 (4.5) | 334 (5.4) | 0.04 |

| Hospital beds >250, No. (%) | 11 795 (42.3) | 8840 (40.8) | 2955 (47.8) | 0.14 | 2916 (47.3) | 2944 (47.8) | 0.01 |

| Teaching hospital, No. (%) | 6704 (24.1) | 5086 (23.5) | 1618 (26.2) | 0.06 | 1523 (24.7) | 1608 (26.1) | 0.03 |

| Weekend admission, No. (%) | 7556 (27.1) | 5848 (27.0) | 1708 (27.6) | 0.01 | 4575 (25.7) | 4464 (27.5) | 0.04 |

Abbreviation: aSBO, adhesive small-bowel obstruction.

Standardized differences are not effected by sample size, allowing for comparisons of baseline characteristics that are not affected by the smaller sample size after matching. A standardized difference of greater than 0.10 suggests negligible correlation between study groups (equivalent to P > .05).29

Overall, 6186 patients (22.2%) underwent operative management at their index admission. Patients treated operatively were younger (mean [SD] age, 60.2 [14.3] vs 61.5 [13.4] years), were more likely to be women (3575 [57.8%] vs 10 653 [49.2%]), and had a lower preadmission comorbidity burden (Table). The probability of being treated surgically decreased with each episode from 22.2% of patients admitted for their index episode of aSBO to 16.6% of patients admitted for their second episode of aSBO to 11.8% of patients admitted for their third episode.

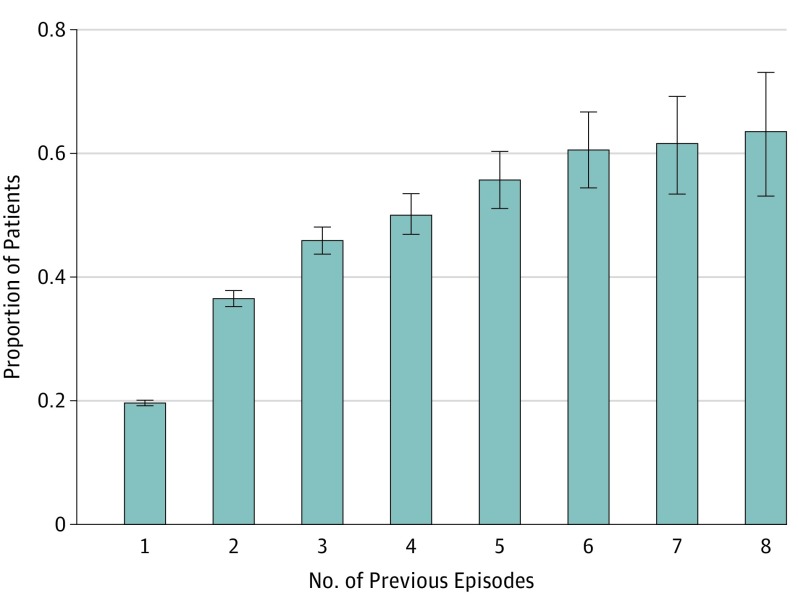

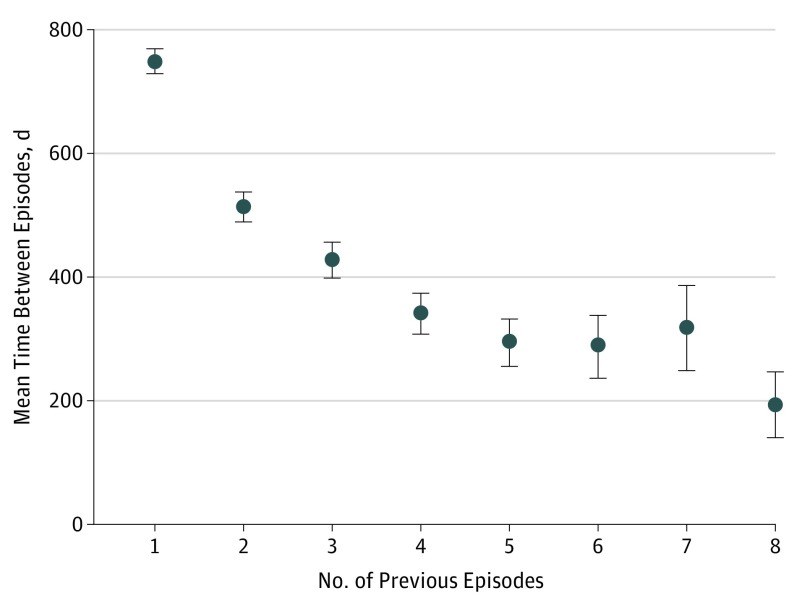

Overall, 19.6% (95% CI,19.2%-20.1%) of patients experienced at least 1 admission for recurrence of aSBO during the study period. With each recurrence, the probability of a subsequent recurrence increased (from 36.5% after the first recurrence to 63.5% after the seventh recurrence [Figure 2]) and the mean time between episodes decreased (from 512 days between the first and second recurrences to 193 days between the sixth and seventh recurrences [Figure 3]). After 3 recurrences of aSBO, the probability of an additional episode was 50% and the mean (SD) time to the next episode was 11 (12) months.

Figure 2. Probability of Additional Recurrences as a Function of the Number of Previous Episodes.

Error bars indicate 95% CI.

Figure 3. Mean Time Between Episodes of Adhesive Small-Bowel Obstruction as a Function of the Number of Previous Episodes.

Error bars indicate 95% CI.

Propensity Matching

After matching patients in the operative and nonoperative cohorts on propensity score, the resulting cohort consisted of 12 320 patients, with 6160 in each group. Balance diagnostics suggested that our cohort was well matched on all patient- and hospital-level characteristics (Table). A comparison of matched patients to unmatched patients may be found in eTable 3 in the Supplement; the results of the propensity score model may be found in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Primary Outcome: Recurrence After the Index Episode

Patients undergoing operative management during their index admission for aSBO had a lower overall risk of recurrence compared with those undergoing nonoperative management (13.0% vs 21.3%; P < .001). The 5-year cumulative incidence of recurrence was also significantly lower among patients undergoing operative management (11.2% vs 19.2%; P < .001). This difference represents an RRR of 41% (95% CI, 36%-46%). When accounting for the competing risk of death, operative management was associated with a significantly lower hazard of recurrence (0.62; 95% CI, 0.56-0.68) (eTables 5 and 7 in the Supplement). When laparoscopy and bowel resection were tested as interaction terms for their effect modification of surgery, neither had a significant effect on the hazard reduction associated with operative intervention (eTable 6 in the Supplement).

Secondary Outcome: Additional Recurrences

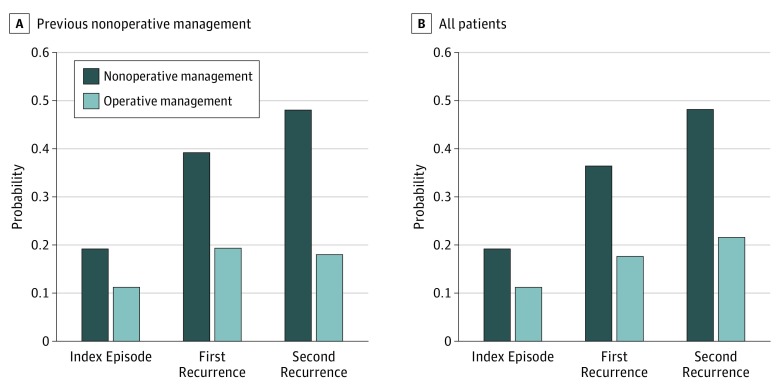

With each episode of aSBO managed nonoperatively, an increase in the 5-year probability of recurrence ranged from 19.2% (95% CI, 18.1%-20.1%) after the first episode to 48.0% (95% CI, 43.0%-53.0%) after the third episode. Further, surgical intervention at any episode was associated with a significantly lower 5-year probability of a subsequent episode. Surgical intervention during the second episode was associated with a significantly lower risk of subsequent recurrence than nonoperative management (19.3% vs 39.2%; RRR, 51%; 95% CI, 34%-63%). The RRR associated with operative management increased with each subsequent episode owing to the increasing additional recurrence risk. Surgical intervention during the third episode was associated with an RRR greater than 50% compared with nonoperative management (18.0% vs 48.0%; RRR, 62%; 95% CI, 32%-79%) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Probability of Recurrence by Management Strategy.

Data are stratified by nonoperative management at all previous episodes (A) or include all patients regardless of previous management (B).

Using a competing risk regression to model the hazard of a subsequent additional recurrence at each episode, surgery was associated with a greater hazard reduction with each episode. For patients who had undergone nonoperative management at all previous episodes, the hazard ratio for an additional recurrence associated with operative management was 0.39 (95% CI, 0.29-0.51) at the second episode and 0.40 (95% CI, 0.24-0.65) at the third episode.

Regardless of how previous episodes were managed, those patients who underwent operative management during their second and third episodes of aSBO had a significantly lower risk of subsequent recurrence than those who underwent nonoperative management. When including all patients with recurrences, the RRR associated with operative management during the second and third episodes of aSBO was 51% (95% CI, 30%-61%) and 55% (95% CI, 35%-70%), respectively (Figure 4B).

Sensitivity Analysis

After excluding patients who underwent operative intervention on postadmission days 0 to 1 (3566 patients [28.9% of matched cohort]), the results were similar to those of the primary analysis. The overall and 5-year risks of recurrence associated with operative and nonoperative management were 14.0% vs 21.3% (P < .001) and 11.7% vs 19.2% (P < .001), respectively. The hazard ratio of recurrence associated with operative management was 0.63 (95% CI, 0.55-0.72; P < .001) compared with nonoperative management.

Discussion

In this longitudinal, retrospective cohort study of patients with their first admission for aSBO, surgical intervention was associated with a significantly lower risk of recurrence. Although the risk of a subsequent recurrence increased with each episode, the disease trajectory could be significantly altered with operative intervention during any episode.

Contrary to surgical dogma, these data suggest that surgical intervention mitigates rather than increases the probability of recurrent aSBO. Further, common belief suggests that patients who have undergone successful nonoperative management during previous admissions are likely to experience resolution without operation on future admissions. Although this might be true, this strategy neglects the potential long-term benefits of surgical intervention.

Our finding that surgical intervention is associated with lower incidence of recurrence is supported by previous studies.14,32,33,34 In another study using population-level data,2 the overall incidence of recurrence was 19% and the 5-year recurrence was 15%. The consistency of these findings suggests validity and generalizability. No previous studies, to our knowledge, have examined the effect of surgical intervention in patients admitted for recurrences of aSBO, which our data suggest represent approximately 25% of all aSBO visits.

Current guidelines for the management of aSBO recommend a trial of nonoperative management in patients without signs of bowel ischemia, with surgical intervention only in the absence of clinical resolution.3,35,36 These guidelines prioritize nonoperative management with the aim of avoiding the risks associated with surgical intervention where possible. The findings of our study suggest that current practice is consistent with these guidelines because only approximately 1 in 5 patients admitted for their index episode underwent surgical intervention.

However, aSBO may be better understood as a long-term, potentially chronic surgical disease. As we have shown, recurrence of aSBO is common and, with each additional episode of aSBO, the risk of subsequent recurrence increases and the time between recurrences decreases. Each admission for aSBO is associated with substantial risks, and the decision to prioritize avoiding surgery in a single admission while neglecting the cost of future recurrences may not consider the potentially recurrent nature of this disease and the risks associated with additional admissions.2

Balancing the immediate risks of operative intervention with the long-term risks associated with recurrence may be challenging. The data presented in this study should guide discussions between patients and their surgeons. We have quantified the risks of recurrence of aSBO and the risk reduction associated with operative intervention. Informed consent for operative or nonoperative management of aSBO requires a discussion of the long-term risks of recurrence associated with both management strategies.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of our study is the longitudinal data that allowed us to track the natural history of aSBO and assess how different management strategies at different times affect the long-term course of the disease. Our data also facilitated identification of deaths during follow-up and the explicit accounting for this competing risk, without which we may have overestimated the hazard of recurrence. Loss to follow-up in this cohort was minimal and would only occur in the event of patients moving out of the province. Given the administrative nature of the data, missing values were negligible.

Although we accounted for measured confounders in our propensity-score matching, important unmeasured confounders also certainly exist. An important unmeasured factor was patients’ surgical history. Patients with complex abdominal surgical histories may have been less likely to receive operative management while also being more likely to experience recurrences of aSBO. However, these patients likely represent a small proportion of the overall population of patients with aSBO. In addition, granularity was limited with respect to clinical and intraoperative data available in the administrative data.

We identified index cases of aSBO using administrative discharge data, and the risk of misclassification bias, particularly with respect to exclusion criteria used to distinguish adhesive and nonadhesive causes of SBO, is another limitation to this study. Finally, estimation of the incidence of recurrence may have been distorted by patients who entered the cohort later in the study period, although the competing risk regressions accounted for this censoring.

This work contributes to the understanding of the natural history of aSBO and the association of different management strategies with the long-term trajectory of this illness. The disease trajectory, characterized by an increasing likelihood of recurrence with each episode, can be significantly altered during any admission.

Conclusions

Surgical intervention for aSBO was associated with a lower risk of recurrent aSBO. Surgery at the index episode is associated with hazard reduction, and surgery during recurrent episodes is also associated with hazard reduction. The long-term risk of recurrence of aSBO should be considered in management in this patient population.

eTable 1. Exclusion Criteria: Nonadhesive Causes of Small-Bowel Obstruction

eTable 2. OHIP Billing Codes for Operative Events

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of Matched and Unmatched Nonoperative Patients

eTable 4. Logistic Model for Propensity Score Estimation (Outcome of Operative Management)

eTable 5. Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression Model (Primary Model)

eTable 6. Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression Model (With Interaction Terms)

eTable 7. Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression Model (Including Covariates From Propensity Model to Test for Residual Confounding Associated With Imbalance)

References

- 1.Millet I, Ruyer A, Alili C, et al. Adhesive small-bowel obstruction: value of CT in identifying findings associated with the effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment. Radiology. 2014;273(2):425-432. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster NM, McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Ko CY. Small bowel obstruction: a population-based appraisal. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(2):170-176. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maung AA, Johnson DC, Piper GL, et al. ; Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma . Evaluation and management of small-bowel obstruction: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73(5)(suppl 4):S362-S369. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827019de [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sikirica V, Bapat B, Candrilli SD, Davis KL, Wilson M, Johns A. The inpatient burden of abdominal and gynecological adhesiolysis in the US. BMC Surg. 2011;11(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-11-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ray NF, Denton WG, Thamer M, Henderson SC, Perry S. Abdominal adhesiolysis: inpatient care and expenditures in the United States in 1994. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(1):1-9. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(97)00127-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullan CP, Siewert B, Eisenberg RL. Small bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(2):W105-W117. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouaïssi M, Gaujoux S, Veyrie N, et al. Post-operative adhesions after digestive surgery: their incidence and prevention: review of the literature. J Visc Surg. 2012;149(2):e104-e114. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arung W, Meurisse M, Detry O. Pathophysiology and prevention of postoperative peritoneal adhesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(41):4545-4553. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i41.4545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dijkstra FR, Nieuwenhuijzen M, Reijnen MM, van Goor H. Recent clinical developments in pathophysiology, epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal adhesions. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2000;(232):52-59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seror D, Feigin E, Szold A, et al. How conservatively can postoperative small bowel obstruction be treated? Am J Surg. 1993;165(1):121-125. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)80414-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka S, Yamamoto T, Kubota D, et al. Predictive factors for surgical indication in adhesive small bowel obstruction. Am J Surg. 2008;196(1):23-27. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong WK, Lim S-B, Choi HS, Jeong S-Y. Conservative management of adhesive small bowel obstructions in patients previously operated on for primary colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(5):926-932. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0423-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams SB, Greenspon J, Young HA, Orkin BA. Small bowel obstruction: conservative vs. surgical management. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(6):1140-1146. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0882-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller G, Boman J, Shrier I, Gordon PH. Natural history of patients with adhesive small bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2000;87(9):1240-1247. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hux JE, Ivis F, Flintoft V, Bica A. Diabetes in Ontario: determination of prevalence and incidence using a validated administrative data algorithm. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):512-516. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying individuals with physician diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6(5):388-394. doi: 10.1080/15412550903140865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jolley RJ, Quan H, Jetté N, et al. Validation and optimisation of an ICD-10–coded case definition for sepsis using administrative health data. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009487. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altoijry A, Al-Omran M, Lindsay TF, Johnston KW, Melo M, Mamdani M. Validity of vascular trauma codes at major trauma centres. Can J Surg. 2013;56(6):405-408. doi: 10.1503/cjs.013412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin PC, Daly PA, Tu JV. A multicenter study of the coding accuracy of hospital discharge administrative data for patients admitted to cardiac care units in Ontario. Am Heart J. 2002;144(2):290-296. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cochran WG. Some methods for strengthening the common χ2 tests. Biometrics. 1954;10(4):417. doi: 10.2307/3001616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiner JP, ed. The Johns Hopkins ACG Case-Mix System Documentation and Application Manual, Version 5.0. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid RJ, Roos NP, MacWilliam L, Frohlich N, Black C. Assessing population health care need using a claims-based ACG morbidity measure: a validation analysis in the Province of Manitoba. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1345-1364. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid RJ, MacWilliam L, Verhulst L, Roos N, Atkinson M. Performance of the ACG case-mix system in two Canadian provinces. Med Care. 2001;39(1):86-99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, Mumford LM. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):452-472. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199105000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kralj B. Measuring “rurality” for purposes of health-care planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Ont Med Rev. 2000;67(9):33-52. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong GY, Mason WM. The hierarchical logistic regression model for multilevel analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1985;80(391):513-524. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1985.10478148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Austin PC. The performance of different propensity-score methods for estimating differences in proportions (risk differences or absolute risk reductions) in observational studies. Stat Med. 2010;29(20):2137-2148. doi: 10.1002/sim.3854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10(2):150-161. doi: 10.1002/pst.433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228-1234. doi: 10.1080/03610910902859574 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies, 2: assessing potential for confounding. BMJ. 2005;330(7497):960-962. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams GL, Gonsalves S, Bandyopadhyay D, Sagar PM. Laparoscopic abdominosacral composite resection for locally advanced primary rectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12(4):299-302. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0439-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duron JJ, Silva NJ, du Montcel ST, et al. Adhesive postoperative small bowel obstruction: incidence and risk factors of recurrence after surgical treatment: a multicenter prospective study. Ann Surg. 2006;244(5):750-757. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000225097.60142.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fevang B-TS, Fevang J, Lie SA, Søreide O, Svanes K, Viste A. Long-term prognosis after operation for adhesive small bowel obstruction. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):193-201. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000132988.50122.de [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catena F, Di Saverio S, Kelly MD, et al. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2010 evidence-based guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Azagury D, Liu RC, Morgan A, Spain DA. Small bowel obstruction: a practical step-by-step evidence-based approach to evaluation, decision making, and management. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(4):661-668. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Exclusion Criteria: Nonadhesive Causes of Small-Bowel Obstruction

eTable 2. OHIP Billing Codes for Operative Events

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of Matched and Unmatched Nonoperative Patients

eTable 4. Logistic Model for Propensity Score Estimation (Outcome of Operative Management)

eTable 5. Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression Model (Primary Model)

eTable 6. Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression Model (With Interaction Terms)

eTable 7. Fine and Gray Competing Risk Regression Model (Including Covariates From Propensity Model to Test for Residual Confounding Associated With Imbalance)