Key Points

Question

What are the lifetime risks for developing hypertension in African American and white individuals using the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2017 threshold for hypertension?

Findings

Blood pressure above the defined hypertension threshold was prevalent in 23.1% of African American men and 30.7% of white men aged 20 to 30 years. The cumulative lifetime risks for hypertension were 84%, 85%, 69%, and 86% for white men, African American men, white women, and African American women, respectively.

Meaning

Lifetime risks for hypertension are high, and efforts to prevent incident hypertension should begin early in life to curb associated morbidity and mortality.

This observational study combines data from 3 large cohorts to quantify lifetime risks for hypertension in white and African American men and women using thresholds derived from 2 separate US national guidelines.

Abstract

Importance

Patterns of hypertension risk development over the adult lifespan and lifetime risks for hypertension under the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) 2017 thresholds for hypertension (≥130/80 mm Hg) are unknown.

Objective

To quantify and compare lifetime risks for hypertension in white and African American men and women under the AHA/ACC 2017 and the Seventh Joint National Commission (JNC7) hypertension thresholds.

Design, Setting, and Participants

We used individual-level pooled data from 3 contemporary cohorts in the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project: the Framingham Offspring Study, the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, and Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. These community-based cohorts included white and African American men and women with blood pressure assessment at multiple cohort examinations.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cumulative lifetime risk for hypertension from ages 20 through 85 years, adjusted for competing risk of death and baseline hypertension prevalence. Incident hypertension under the AHA/ACC threshold was defined by a single-occasion blood pressure measurement of 130/80 mm Hg or more or self-reported use of antihypertensive medications. Incident hypertension under the JNC7 threshold was defined by a single-occasion blood pressure measurement of 140/90 mm Hg or more or the use of antihypertensive medications.

Results

A total of 13 160 participants contributed 227 600 person-years of follow-up; the data set included individual-level data on 6313 participants at baseline (median age, 25 years), plus person-year data from participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities and Framingham Offspring studies who enrolled at older ages. Baseline prevalence of hypertension under the AHA/ACC 2017 threshold in participants entering the data set between 20 and 30 years of age was 30.7% in white men (n = 549 of 1790), 23.1% in African American men (n = 245 of 1063), 10.2% in white women (n = 210 of 2070), and 12.3% in African American women (n = 171 of 1390). White men had lifetime risk of hypertension of 83.8% (95% CI, 82.5%-85.0%); African American men, 86.1% (95% CI, 84.1%-88.1%); white women, 69.3% (95% CI, 67.8%-70.7%); and African American women, 85.7% (95% CI, 84.0%-87.5%). These were greater than corresponding lifetime risks under the JNC7 threshold for hypertension (white men, 60.5% [95% CI, 58.9%-62.1%]; African American men, 74.7% [95% CI, 71.9%-77.5%]; white women, 53.9% [95% CI, 52.5%-55.4%]; and African American women, 77.3% [95% CI, 75.0%-79.5%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Under the AHA/ACC 2017 blood pressure threshold for hypertension, lifetime risks for hypertension exceeded 75% for African American men and women and white men. Furthermore, prevalence of blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg or more is very high in young adulthood, suggesting that efforts to prevent development of hypertension should be focused early in the life course.

Introduction

In an effort to increase awareness of hypertension and prevent the cumulative end-organ damage from nonoptimal blood pressure and subsequent cardiovascular events, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) reduced the diagnostic threshold for hypertension in 2017 from the Seventh Joint National Commission (JNC7) definition of 140/90 mm Hg or more to 130/80 mm Hg or more.1 Quantitation of the cumulative lifetime risks for hypertension may help public health officials identify groups at high risk for hypertension who may benefit from more aggressive lifestyle modification, screening, and medical therapy to prevent associated illnesses later in life. Existing estimates of lifetime risks for hypertension are based on JNC7 thresholds, are limited in racial diversity, or do not provide risk estimates over the entire adult life course.2,3,4 Therefore, we used data from the Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project to generate cumulative lifetime risks estimates for hypertension under JNC7 and AHA/ACC 2017 thresholds from ages 20 to 85 years in African American and white men and women.

Methods

Study Population

We used 3 contemporaneous Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project cohorts that enrolled and followed up large numbers of African American and white participants from the 1970s to the present, provided in-office blood pressure follow-up examinations, and had nearly 100% vital status ascertainment: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, and Framingham Offspring Study (FOS). Enrollment times, ages, sample sizes, and follow-up frequencies are summarized elsewhere.5 Briefly, the Framingham Offspring Study enrolled white participants in 1971 and followed up 5124 participants aged 5 to 70 years for up to 48 years. CARDIA enrolled white and African American participants in 1985 and 1986 and has followed up 5115 participants aged 18 to 30 years for 34 years. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study enrolled white and African American participants in 1987 through 1989 and followed up 15 792 participants aged 45 to 64 years for 20 years.

Individuals were included in the present analysis if they had demographic data and assessment of blood pressure levels and antihypertensive medication use at multiple examinations. The Cardiovascular Lifetime Risk Pooling Project, a deidentified data set, was approved by the institutional review board at Northwestern University. Informed consent was obtained by cohort staff at the time of participant enrollment.

Measurements

Blood pressure in CARDIA and ARIC was taken as the mean of the last 2 of 3 seated measurements, while in FOS, blood pressure was recorded as a mean of 2 measurements.6,7,8 Sex, race, and medication use were self-reported. In the present analysis, incident hypertension under AHA/ACC 2017 guidelines was defined by the first visit with a blood pressure level of 130/80 or more (ie, a systolic blood pressure reading of ≥130 mm Hg and/or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥80 mm Hg) or participant-reported use of blood pressure–lowering medication. As in existing studies, incident hypertension under JNC7 guidelines was defined by the first visit with a blood pressure level of 140/80 or more or participant-reported use of blood pressure–lowering medication.

Statistical Analysis

Individual-level data from FOS, CARDIA, and ARIC were pooled after the magnitude and patterns in cumulative incidence for hypertension were found to be similar across cohorts. The lifetime risk analysis was based on a modified Kaplan-Meier analysis that used age as the time scale.9,10 In this analysis, individuals of different ages contributed person-years to the estimates even if they were not enrolled during the baseline age. Lifetime risks were adjusted for the competing risk of death, and 95% CIs were generated by the practical incidence estimator.10 Adjustment for baseline prevalence of hypertension allowed for estimation of cumulative risk from birth until a given age.11 Baseline prevalence of hypertension was estimated using data from participants enrolled in CARDIA or FOS between the ages of 20 to 30 years. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Data analysis took place from January 2018 to July 2018.

Results

A total of 13 160 participants from CARDIA, FOS, and ARIC were free of hypertension at their baseline examinations and were followed up for a total of 227 600 person-years. The data set included individual-level data on 6313 participants at baseline (median age, 25 years), plus person-year data from participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities and Framingham Offspring studies who enrolled at older ages. The baseline characteristics of participants entering the analysis at 20 to 30 years are presented in the Table. This baseline group was 54.8% female (2070 white women and 1390 African American women) and 38.9% African American (1390 African American women and 1063 African American men). Mean (SD) body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was lowest for white women (23.1 [4.3]) and highest for African American women (26.1 [6.6]). Cohort-specific characteristics are presented in eTables 1, 2, and 3 in the Supplement.

Table. Baseline Characteristics for Lifetime Risks of Hypertension by American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology 2017 Blood Pressure Threshold by Race and Sex.

| Characteristic | White Men (n = 1790) | African American Men (n = 1063) | White Women (n = 2070) | African American Women (n = 1390) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 25.7 (3.0) | 24.5 (3.2) | 25.7 (3.0) | 24.7 (3.4) |

| Comorbid conditions, No. (%) | ||||

| Hypertensiona | 549 (30.7) | 245 (23.1) | 210 (10.1) | 171 (12.3) |

| Diabetes | 8 (0.5) | 6 (0.6) | 10 (0.5) | 14 (1.0) |

| Current smoking | 611 (34.4) | 389 (36.9) | 705 (34.2) | 434 (31.4) |

| Laboratory values, mean (SD) | ||||

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | ||||

| Systolic | 117.0 (11.2) | 115.8 (10.5) | 107.0 (10.2) | 107.9 (10.1) |

| Diastolic | 73.3 (9.6) | 70.7 (10.2) | 68.1 (8.5) | 67.2 (9.7) |

| BMI | 24.8 (3.7) | 24.7 (4.3) | 23.1 (4.3) | 26.1 (6.6) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 179 (34) | 177 (35) | 177 (32) | 177 (33) |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 46 (11) | 54 (14) | 56 (13) | 55 (13) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

SI conversion factor: To convert total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply values by 0.0259.

As defined by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology 2017 guidelines.

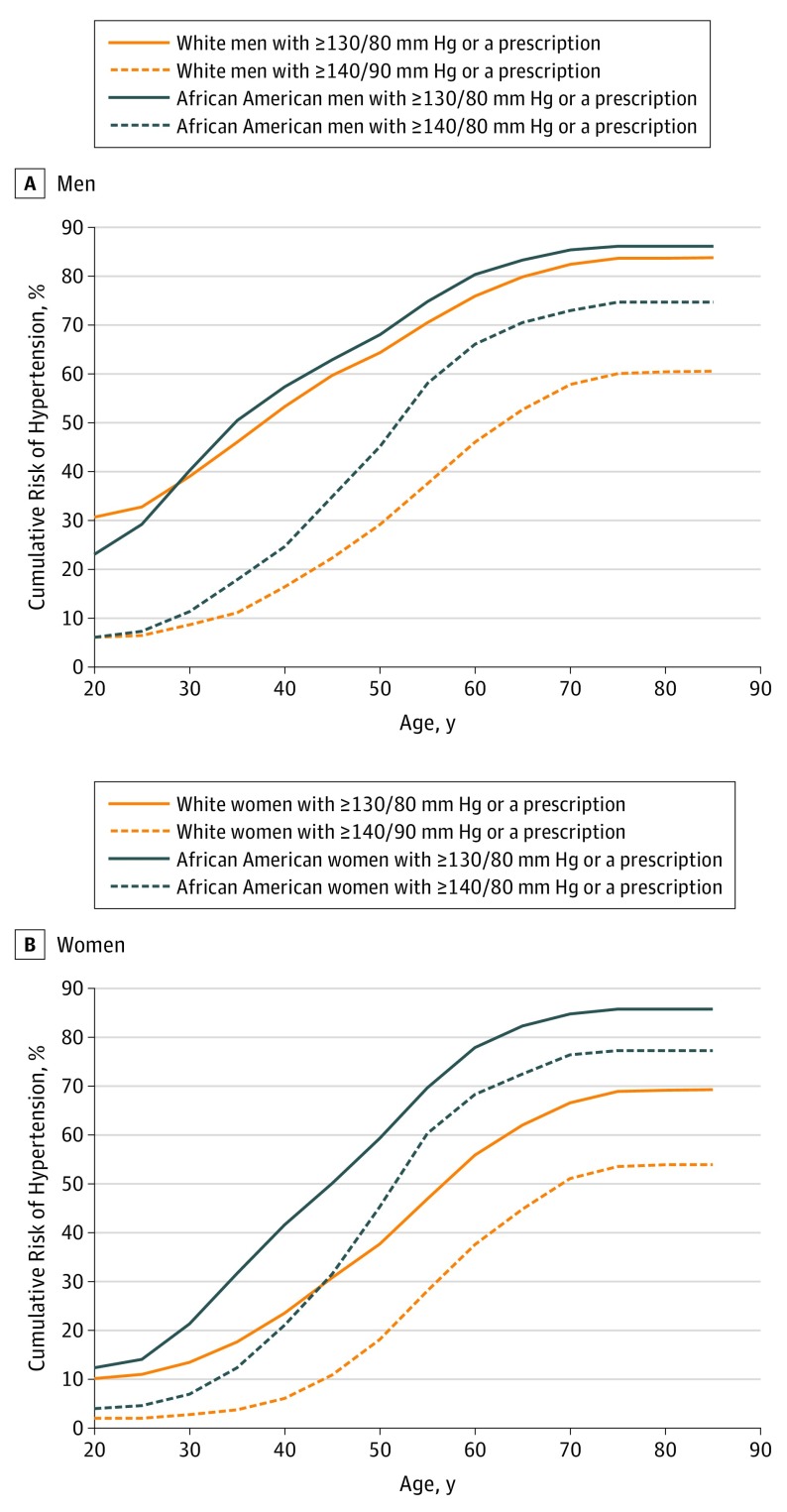

The cumulative lifetime risk estimates for hypertension stratified by race and sex are presented in the Figure. Under the JNC7 threshold, baseline hypertension prevalence for African American men and white men was 6.0% in both groups (64 of 1063 African American men and 107 of 1790 white men); cumulative lifetime risks for hypertension were 74.7% (95% CI, 71.9%-77.5%) and 60.5% (95% CI, 58.9%-62.1%), respectively. Both African American men and white men had higher lifetime risks for hypertension under the AHA/ACC 2017 threshold: baseline hypertension prevalence for these 2 groups was 23.1% (n = 245 of 1063) and 30.7% (n = 549 of 1790), and cumulative lifetime risks for hypertension were 86.1% (95% CI, 84.1%-88.1%) and 83.8% (95% CI, 82.5%-85.0%), respectively.

Figure. Race-Stratified Cumulative Risks for Hypertension in Men and Women by the Seventh Joint National Commission and American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology 2017 Blood Pressure Thresholds.

Solid black lines and solid orange lines represent cumulative risk for hypertension under the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology 2017 guidelines in African American individuals and white individuals, respectively. Dashed black lines and dashed orange lines represent cumulative risk for hypertension under the Seventh Joint National Commission threshold in African American individuals and white individuals, respectively. These risk curves represent the sum of age-specific cumulative incidence for hypertension by sex and race groups. Numbers of individuals in the risk set will increase or decrease with increasing age, because older individuals contributed person-years of data to age-specific risk estimates for their age at cohort enrollment until they were censored. Thus, number at risk tables are not included.

Under JNC7 guidelines, baseline prevalence of hypertension was 4.0% (n = 56 of 1390) in African American women and 2.0% in white women (n = 41 of 2070); lifetime risks of hypertension to 85 years of age were 77.3% (95% CI, 75.0%-79.5%) for African American women and 53.9% (95% CI, 52.5%-55.4%) for white women. Under AHA/ACC 2017 guidelines, baseline prevalence rates were 12.3% (n = 171 of 1390) and 10.1% (n = 210 of 2070) in African American and white women, and cumulative lifetime risks were 85.7% (95% CI, 84.0%-87.5%) and 69.3% (95% CI, 67.8%-70.7%), respectively.

Discussion

This pooled cohort analysis demonstrates that cumulative lifetime risks for incident hypertension under the AHA/ACC thresholds are greater than 75% for African American men and women and white men. The increase in lifetime risk under the new, lower blood pressure threshold is more notable for white individuals than for African American individuals and was greatest in young white men. The high prevalence of hypertension at ages 20 to 30 years underscores the importance of hypertension awareness and primordial prevention targeting children, adolescents, and young adults.

Although differences in the age and cumulative risk for hypertension exist across some race and sex groups, the estimates reported here are very high for all groups. Once hypertension is present, substantial reductions in cardiovascular risk have been demonstrated with blood pressure–lowering pharmacotherapy. However, individuals with hypertension who are treated do not achieve the same level of risk that they would have if they had never had hypertension.12 Thus, aggressive efforts must be made to promote heart-healthy lifestyle habits earlier in the life course to reduce incident hypertension.

Interestingly, under the AHA/ACC 2017 blood pressure threshold, the lifetime risk for incident hypertension is not substantially different between white and African American men. This finding suggests that a larger proportion of white men have systolic blood pressure values between 130 and 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure values between 80 and 90 mm Hg than do African American men. Thus, the population of African American men has a greater number of individuals with more severe elevations (≥140/90 mm Hg) in blood pressure. This is consistent with previously reported population estimates of blood pressure levels in African American and white men.13 However, the attenuation of difference in lifetime risk between African American and white men should not be misinterpreted to indicate an attenuation of disparities in hypertension-associated illness, because African American men may have higher mean blood pressure levels, poorer blood pressure control when receiving pharmacotherapy, and other unmeasured factors that may drive documented differences in incident stroke, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure across racial/ethnic groups.14,15

African American women have similar lifetime risks for hypertension as white men and African American men. This again demonstrates the substantial risks for hypertension-associated illnesses that have been observed in African American women.

Limitations

There is a risk of confounding by birth cohort in the lifetime risks in this study, because CARDIA exclusively enrolled younger participants (18-30 years old), while ARIC exclusively enrolled middle-aged participants (45-64 years old). However, similar patterns in cohort-specific risk curves prior to pooling assured that pooling was qualitatively appropriate (eFigure in the Supplement). The alternative to pooling prospective cohorts together to assess lifetime risks is to follow up 1 cohort over a lifespan. By the time such a study completes follow-up, the risk curves would likely no longer reflect population patterns of underlying determinants, and the lifetime risks would no longer be informative of the public health burden.

Finally, we report lifetime risk estimates for hypertension defined by a single cohort examination with blood pressure level above the AHA/ACC and JNC7 thresholds or self-reported medication use. This approach could overestimate hypertension rates by the ACC/AHA 2017 clinical definition of elevated blood pressure levels on 2 or more clinical encounters.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate high lifetime risks of hypertension for African American and white men and women in the United States. Risks of hypertension are substantially higher and occur earlier under the AHA/ACC 2017 hypertension threshold than the JNC7 threshold. Blood pressure awareness and primordial prevention early in the life course is needed to curb the epidemic of hypertension-associated diseases.

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of ARIC Study Sample by Race and Sex Group

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of CARDIA Study Sample by Race and Sex Group

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of FOS Study Sample by Race and Sex Group

eFigure. Cohort-Specific Cumulative Risks for HTN under AHA/ACC Threshold, Adjusted for Cohort Baseline Prevalence

eReferences.

References

- 1.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. . 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary, a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1269-1324. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, et al. . Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 2002;287(8):1003-1010. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.8.1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson AP, Howard G, Burke GL, Shea S, Levitan EB, Muntner P. Ethnic differences in hypertension incidence among middle-aged and older adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2011;57(6):1101-1107. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas SJ, Booth JN III, Dai C, et al. . Cumulative incidence of hypertension by 55 years of age in blacks and whites: the CARDIA study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(14):e007988. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkins JT, Karmali KN, Huffman MD, et al. . Data resource profile: the Cardiovascular Disease Lifetime Risk Pooling Project. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(5):1557-1564. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. The Framingham Offspring Study: design and preliminary data. Prev Med. 1975;4(4):518-525. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(75)90037-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. . CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105-1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The ARIC Investigators The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687-702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Beiser A, Levy D. Lifetime risk of developing coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1999;353(9147):89-92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10279-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beiser A, D’Agostino RB Sr, Seshadri S, Sullivan LM, Wolf PA. Computing estimates of incidence, including lifetime risk: Alzheimer’s disease in the Framingham study, the practical incidence estimators (PIE) macro. Stat Med. 2000;19(11-12):1495-1522. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Beiser AS, Cobain MR, Vasan RS. Estimating lifetime risk of developing high serum total cholesterol: adjustment for baseline prevalence and single-occasion measurements. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(4):464-472. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu K, Colangelo LA, Daviglus ML, et al. . Can antihypertensive treatment restore the risk of cardiovascular disease to ideal levels?: the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study and the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(9):e002275. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; and Stroke Council . Cardiovascular health in African Americans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136(21):e393-e423. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon S, Burt V, Carroll LT Hypertension among adults in the United States, 2009-2010. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db107.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed February 21, 2019. [PubMed]

- 15.Howard G, Banach M, Cushman M, et al. . Is blood pressure control for stroke prevention the correct goal? the lost opportunity of preventing hypertension. Stroke. 2015;46(6):1595-1600. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics of ARIC Study Sample by Race and Sex Group

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of CARDIA Study Sample by Race and Sex Group

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics of FOS Study Sample by Race and Sex Group

eFigure. Cohort-Specific Cumulative Risks for HTN under AHA/ACC Threshold, Adjusted for Cohort Baseline Prevalence

eReferences.