Key Points

Question

What is the association of tranexamic acid use with decreased intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis in patients undergoing primary rhinoplasty?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis (5 studies comprising 332 patients) indicated that tranexamic acid has the ability to significantly reduce intraoperative blood loss by −41.6 mL compared with controls. Tranexamic acid was also able to reduce postoperative edema and ecchymosis compared with controls.

Meaning

Plastic surgeons should consider using tranexamic acid when performing rhinoplasties.

This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the role of tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis among patients undergoing primary elective rhinoplasty.

Abstract

Importance

Blood loss from surgical procedures is a major issue worldwide as the demand for blood products is increasing. Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent commonly used to reduce intraoperative blood loss.

Objective

To systematically examine the role of tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis among patients undergoing primary elective rhinoplasty.

Data Sources

A systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken in an academic medical setting using Medline, Embase, and Google Scholar from inception to June 30, 2018. All references of included articles were screened for potential inclusion. The search was mapped to Medical Subject Headings, and the following terms were used to identify potential articles: reconstruction or rhinoplasty and tranexamic acid or anti-fibrinolysis or antifibrinolysis and bleeding or ecchymosis or bruising or edema or complications.

Study Selection

The population of interest consisted of adult patients undergoing primary elective rhinoplasty. The intervention was the use of tranexamic acid. The control group was composed of patients receiving a placebo. Primary outcomes were intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis. In vitro or animal studies were excluded, and only English-language articles were included.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

The PRISMA guidelines were followed, and articles were assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines. Random-effects meta-analysis was performed to determine the overall effect size.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcomes were intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis.

Results

Five studies (comprising 332 patients) were included in the qualitative analysis, all of which were randomized clinical trials published within the past 5 years. The mean (SD) patient age was 27 (7) years (age range, 16-42 years), while the mean (SD) sample size was 66 (19) (range, 50-96). Meta-analysis of 4 studies (271 patients) indicated that tranexamic acid treatment resulted in a mean reduction in intraoperative blood loss of −41.6 mL (95% CI, −69.8 to −13.4 mL) compared with controls (P = .004). Three studies indicated that postoperative edema and ecchymosis were reduced with tranexamic acid treatment compared with controls; however, there was no significant difference compared with corticosteroid use. Four studies were considered of high methodological quality, with a low risk of bias. The overall quality of evidence was high.

Conclusions and Relevance

Tranexamic acid has the ability to significantly reduce intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis among patients undergoing primary elective rhinoplasty.

Level of Evidence

4.

Introduction

Rhinoplasty is one of the most common aesthetic procedures performed by plastic surgeons, with an estimated 218 000 such operations performed annually in the United States alone.1 Blood loss, edema, and ecchymosis are common complications of rhinoplasty that can place physical and psychological stress on patients.2,3 Blood loss can lead to transfusion and associated complications of infection, allergic reaction, and overall increased risk of mortality.4 Furthermore, generalized swelling negatively alters the ability of both the surgeon and the patient to assess outcomes shortly after the procedure, while periorbital swelling may restrict the patient’s vision. Taken together, the prospect of these symptoms may deter many patients from considering rhinoplasty as a treatment option.3

Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent that has been used for decades in multiple surgical disciplines for its ability to reduce intraoperative blood loss and the need for blood transfusions.5,6 Evidence suggests that tranexamic acid may also reduce postoperative edema and ecchymosis.7 Tranexamic acid has been shown to be a safe medication,5,8 with reported rates of serious complications, such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, similar to those of common medications like aspirin and warfarin sodium.9 The use of tranexamic acid is well established in reconstructive craniofacial surgery10,11; however, it is not commonly used in aesthetic plastic surgery. In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we examined the role of tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis among patients undergoing primary elective rhinoplasty.

Methods

Protocol and Eligibility Criteria

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines were followed in the performance and reporting of this systematic review and meta-analysis.12 The population of interest in this study consisted of adult patients undergoing primary elective rhinoplasty. The intervention considered was the use of tranexamic acid. A control group was composed of patients receiving a placebo solution, such as normal saline. The primary outcomes of interest were intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis. This article conforms to the guidelines set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki.13

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken in an academic medical setting. The following electronic databases were searched from inception to June 30, 2018, to identify relevant studies: MEDLINE, Embase, and Google Scholar. The search was mapped to Medical Subject Headings, and the following terms were used to identify potential articles: reconstruction or rhinoplasty and tranexamic acid or anti-fibrinolysis or antifibrinolysis and bleeding or ecchymosis or bruising or edema or complications. In addition, all references of included articles were screened for potential inclusion. Comparative and single-arm studies were included. Only English-language articles were included. In vitro or animal studies were excluded. Two of us (C.M. and S.N.) independently screened titles and abstracts to assess eligibility for inclusion. When inclusion was uncertain, a third author was contacted (O.A.S.), and the full text was retrieved if needed. Two of us (C.M. and O.A.S.) then independently reviewed the studies based on the full-text article, and eligibility was decided by consensus. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion and consensus between the reviewers.

Data Extraction

The following variables were extracted from each article and used for comparisons: author, year of publication, journal, country, study design, age of patients, sample size, funding, tranexamic acid dosing, indication for surgery, number of prior nasal surgical procedures, control treatment, other comparison treatment (eg, corticosteroids), follow-up time, outcome measurement, and study results. The level of evidence of primary studies was also assessed using the following established hierarchy: (1) high-quality multicenter or single-center randomized clinical trials with adequate power or systematic review of these studies; (2) lesser-quality randomized clinical trials, prospective cohort, or comparative study or systematic review of these studies; (3) retrospective cohort or comparative study, case-control study, or systematic review of these studies; (4) case series with pretest/posttest or only posttest results; (5) expert opinion developed via consensus process, case report or clinical example, or evidence-based physiology).14 Data were extracted by 2 independent reviewers (C.M. and S.N.) using a data collection spreadsheet (Excel; Microsoft Corp) designed a priori.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

Articles were assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias, which is a means of determining the internal validity of randomized clinical trials by focusing on 5 distinct methodologically important domains (eTable in the Supplement).15 The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias does not provide a summed total score for each study but instead assesses each domain for high, low, or unclear risk of bias.15 The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines were used to rate the overall quality of the body of evidence surrounding each of the 3 outcomes.16 Random-effects meta-analysis was performed to determine the overall effect size.

Analysis of Heterogeneity

Studies were examined to determine if significant clinical heterogeneity existed. Clinical heterogeneity can be defined as differences in the study population associated with, but not limited to, participant characteristics, study setting, timing of outcomes, and intervention characteristics. If articles contained significant heterogeneity, this was taken into account when formulating final conclusions and when determining the appropriateness of conducting a meta-analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were generated for all variables. Categorical factors were assessed using frequencies and percentages. All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24; IBM SPSS Statistics). Meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model with Review Manager (version 5.3; Nordic Cochrane Center, Cochrane Collaboration). Statistical significance was set at 2-sided P < .05.

Results

Study Identification and Selection

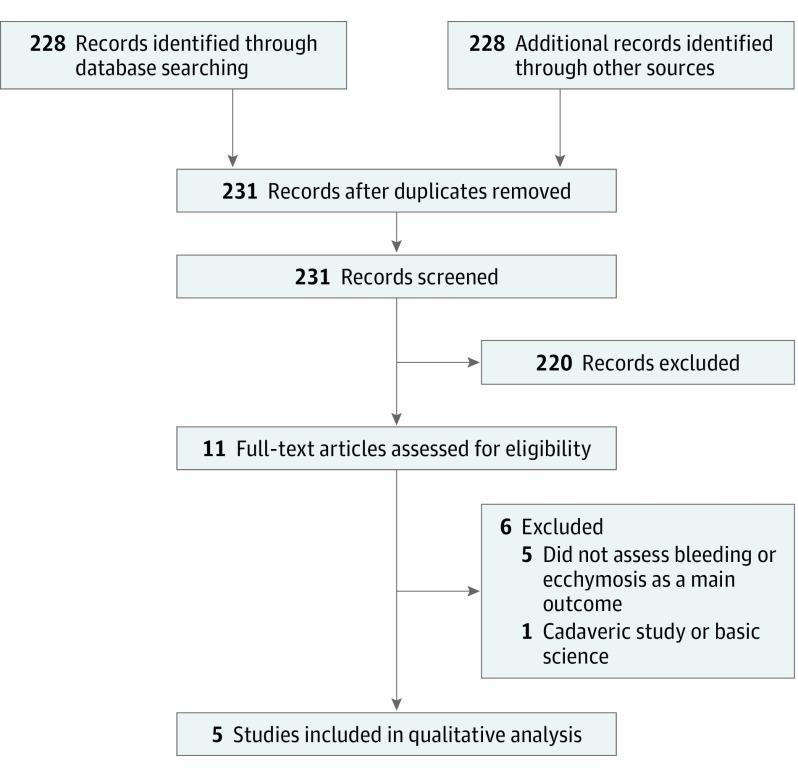

Figure 1 shows the search strategy to identify articles. The initial search yielded a total of 231 articles, of which 11 were potentially relevant after title review. Of the 5 included studies, 4 were identified from the computerized database search and 1 from a bibliography search.

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram Showing the Search Strategy.

Five studies17,18,19,20,21 were included in the qualitative analysis. PRISMA indicates Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis.

Characteristics of Included Studies

Table 1 lists the characteristics of 5 studies included in the qualitative analysis. All 5 were randomized clinical trials, 4 conducted in Iran and 1 in Turkey, and their level of evidence was 1 or 2. All studies were published within the past 5 years across a variety of different journals. The age of patients ranged from 16 to 42 years, with a mean (SD) age of 27 (7) years. The mean(SD) sample size was 66 (19), with a range of 50 to 96. Two studies17,18 received funding from local university medical schools.

Table 1. Characteristics of 5 Included Studies Assessing the Role of Tranexamic Acid in Reducing Intraoperative Bleeding and Postoperative Edema and Ecchymosis in Primary Elective Rhinoplasty.

| Characteristic | No. of Studies |

|---|---|

| Year of publication | |

| 2015 | 2 |

| 2016 | 1 |

| 2017 | 1 |

| 2018 | 1 |

| Journal | |

| Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal | 1 |

| The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery | 1 |

| Journal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery | 1 |

| Aesthetic Plastic Surgery | 1 |

| Annals of Plastic Surgery | 1 |

| Country | |

| Iran | 4 |

| Turkey | 1 |

| Study design | |

| Randomized clinical trial | 5 |

| Level of evidence | |

| 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 1 |

| Age of patients, mean (SD) [range] | 27 (7) [16-42] |

| Sample size, mean (SD) [range] | 66 (19) [50-96] |

| Funding | |

| None | 3 |

| University medical school | 2 |

| Tranexamic acid dosing | |

| 10 mg/kg Before surgery | 2 |

| 10 mg/kg Before surgery, 3 doses every 8 h after surgery | 1 |

| 1 g 2 h Before surgery | 1 |

| 1 g 2 h Before surgery, 1 g 3 times a day for 5 d after surgery | 1 |

| Placebo dosing | |

| Placebo pill | 3 |

| 10 mL Normal saline | 1 |

| 20 mL Normal saline | 1 |

| Other intervention dosing | |

| None | 3 |

| 8 mg IV dexamethasone, 8 mg IV dexamethasone plus 10 mg/kg tranexamic acid | 1 |

| 1 mg/kg IV methylprednisolone | 1 |

| Clinical heterogeneity | |

| Homogeneous | 5 |

Abbreviation: IV, intravenous.

Tranexamic acid dosing varied between studies. Two studies17,19 gave 1 dose based on weight immediately before surgery, 1 study20 gave 1 dose based on weight before surgery and 1 dose after surgery every 8 hours for 24 hours, 1 study18 gave 1 g 2 hours before surgery, and 1 study21 gave 1 g 2 hours before surgery and 1 g 3 times daily for 5 days after surgery. Placebo dosing was in pill form for 3 studies18,20,21 and as intravenous (IV) normal saline for 2 studies.17,19 Two studies20,21 examined the use of corticosteroids in addition to tranexamic acid for the treatment of bleeding and ecchymosis. One study20 used IV dexamethasone separately and together with tranexamic acid, while another study21 compared the use of tranexamic acid with a weight-based dose of IV methylprednisolone.

Outcome Measures and Findings

The methods to measure intraoperative blood loss were consistent between studies (Table 2). The 4 studies17,18,19,21 measuring blood loss measured the volume of suction and the amount and weight of bloody gauzes to determine the total milliliters of blood lost. Ghavimi et al19 also used measurements of hemoglobin and hematocrit on postoperative day 3 to quantify blood loss. Methods to measure edema and ecchymosis varied between studies. Ghavimi et al19 used an a priori standardized scale with pictures to grade edema and ecchymosis on postoperative day 1. Mehdizadeh et al20 took photographs of participants on postoperative days 1, 3, and 7, which were then examined by a masked plastic surgeon using a standardized scale. Sakallioğlu et al21 used the same method as Mehdizadeh et al,20 with the difference being that each image was graded by 2 masked plastic surgeons instead of 1.

Table 2. Summary of 5 Included Studies Assessing the Role of Tranexamic Acid in Reducing Intraoperative Bleeding and Postoperative Edema and Ecchymosis in Primary Elective Rhinoplasty.

| Source | Sample Size | Follow-up Time | Tranexamic Acid Dosing | Outcome Measurement | Study Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beikaei et al,17 2015 | 96 (48 Tranexamic acid, 48 control) in 2011 | 1 d | 10 mg/kg Tranexamic acid before surgery | Calculated blood loss (suction, sponges, etc) | Mean (SD) blood loss of 43.3 (11.0) mL with tranexamic acid vs 60.3 (9.5) mL in control (P < .001), patient weight and duration of surgery associated with the amount of bleeding |

| Eftekharian and Rajabzadeh,18 2016 | 50 (25 Tranexamic acid, 25 control) | 1 d | 1 g Tranexamic acid 2 h before surgery | Calculated blood loss (suction, sponges, etc) | Mean (SD) blood loss of 144.6 (60.3) mL in tranexamic acid group and 199.6 (73.1) mL in control (P < .05), shorter operating room time and better aesthetic outcome in tranexamic acid group |

| Ghavimi et al,19 2017 | 50 (24 Tranexamic acid, 26 control) | 3 d For hemoglobin and hematocrit, 24 h for edema and ecchymosis | 10 mg/kg Tranexamic acid before surgery | Calculated blood loss (suction, sponges, etc), hemoglobin and hematocrit at 3 d after surgery, edema and ecchymosis measured using a standardized scale after 24 h | Mean (SD) blood loss of 216 (65) mL in tranexamic acid vs 254 (55) mL in control (P = .013); hemoglobin 266.7 in tranexamic acid vs 241.3 in control (P = .1); hematocrit 247.1 in tranexamic acid vs 279.2 in control (P = .03); tranexamic acid better than control for eyelid edema, periorbital ecchymosis, and surgeon satisfaction |

| Mehdizadeh et al,20 2018 | 61 (15 Tranexamic acid, 16 dexamethasone, 15 tranexamic acid plus dexamethasone, 15 control) | 7 d | 10 mg/kg Tranexamic acid 1 h before surgery and 1 dose every 8 h after surgery for 24 h | Photographs 1, 3, and 7 d after surgery examined by an independent plastic surgeon for edema and ecchymosis | In tranexamic acid, dexamethasone, and tranexamic acid plus dexamethasone groups, edema and ecchymosis were lower; no difference comparing tranexamic acid, dexamethasone, and dexamethasone plus tranexamic acid on any postoperative day; no difference in duration of surgery between any group |

| Sakallioğlu et al,21 2015 | 75 (25 Tranexamic acid, 25 methylprednisolone, 25 control) | 7 d | 1 g Tranexamic acid 2 h before surgery and 1 g 3 times a day for 5 d after surgery | Calculated blood loss (suction, sponges, etc); photographs 1, 3, and 7 d after surgery examined by 2 independent plastic surgeons for edema and ecchymosis | Amount of bleeding lower in tranexamic acid group compared with methylprednisolone and control groups, edema and ecchymosis better in tranexamic acid and methylprednisolone groups compared with control but no difference between tranexamic acid and methylprednisolone groups for edema and ecchymosis |

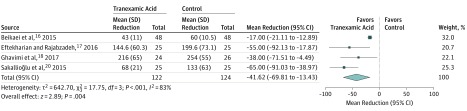

Figure 2 shows the results of the meta-analysis completed on 4 studies that reported on intraoperative blood loss.17,18,19,21 The meta-analysis indicated that tranexamic acid treatment resulted in a mean reduction in intraoperative blood loss of −41.6 mL (95% CI, −69.8 to −13.4 mL) compared with controls (P = .004). The results of the 5 included studies are summarized in Table 2. All 5 studies were comparative in nature. Among the 4 studies that examined the role of tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative blood loss, all 4 studies showed significantly less blood loss compared with controls17,18,19,21 or methylprednisolone.21 In a multivariable analysis, Beikaei et al17 found that patient weight and duration of surgery were associated with the amount of blood loss. Eftekharian et al18 reported that patients treated with tranexamic acid also had shorter duration of surgery compared with controls and in general had better aesthetic outcomes. Ghavimi et al19 observed that levels of hemoglobin were not significantly different among groups treated with tranexamic acid vs placebo, while hematocrits were statistically different. Treatment with tranexamic acid was also associated with less edema, decreased periorbital ecchymosis, and greater surgeon satisfaction with the procedure.19

Figure 2. Meta-analysis Results of Assessing the Role of Tranexamic Acid in Reducing Intraoperative Blood Loss During Primary Elective Rhinoplasty.

Four studies17,18,19,21 that reported on intraoperative blood loss were included in the meta-analysis.

When examining edema and ecchymosis, Mehdizadeh et al20 found that patients treated with tranexamic acid alone, tranexamic acid combined with dexamethasone (IV 8 mg 1 hour before surgery and 1 dose every 8 hours for 24 hours after surgery), or dexamethasone alone (IV 8 mg 1 hour before surgery and 1 dose every 8 hours for 24 hours after surgery) had significantly less edema and ecchymosis compared with controls. Despite this, there were no differences in edema and ecchymosis between the 3 treatment groups and no difference in duration of surgery between the treatment groups and the control group.20 Sakallioğlu et al21 observed that patients treated with tranexamic acid and methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg IV methylprednisolone before surgery) had less edema and ecchymosis compared with controls. There was no statistical difference when comparing treatment with tranexamic acid vs methylprednisolone.

Analysis of Heterogeneity

All included studies were considered to be clinically homogeneous because authors were diligent in ensuring that demographic characteristics, interventions, outcome measurements, and follow-up time were consistent between treatment and control groups (Table 1 and Table 2). Due to the low degree of clinical heterogeneity between studies, a meta-analysis was performed to compare treatment with tranexamic acid vs controls for the outcome of intraoperative blood loss.

Risk of Bias in Included Studies and Level of Evidence

Assessment of included studies using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias indicated that 4 studies17,18,19,20 among the 5 were of high quality and unlikely to have considerable biases (Table 3). Eftekharian et al18 did not provide sufficient evidence to indicate that allocation concealment was properly undertaken between intervention and control groups and were given an “unclear risk of bias” judgment for that domain. Sakallioğlu et al21 completed a randomized trial, but the study was thought to be at a high risk of bias due to the lack of masking of participants, personnel, and outcome assessment. The authors did not mention any sort of masking in their study, which indicates that the internal validity of their study may be flawed and prone to considerable bias. In addition, it was unclear whether allocation concealment was properly completed, and it was not sufficiently reported.

Table 3. Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias for Each of 5 Studies Included in the Qualitative Analysis.

| Source | Selection Bias: Random Sequence Generation | Selection Bias: Allocation Concealment | Reporting Bias: Selective Reporting | Other Bias: Other Sources of Bias | Performance Bias: Masking (Participants and Personnel) | Detection Bias: Masking (Outcome Assessment) | Attrition Bias: Incomplete Outcome Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beikaei et al,17 2015 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Eftekharian and Rajabzadeh,18 2016 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ghavimi et al,19 2017 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Mehdizadeh et al,20 2018 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Sakallioğlu et al,21 2015 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | High | High | Low |

Overall Grade of Recommendation

Based on the results of the meta-analysis, the low degree of heterogeneity, and the consistency of outcomes, the overall quality of evidence was high using the GRADE guidelines for the use of tranexamic acid to reduce intraoperative blood loss in elective primary rhinoplasty. The quality of evidence for the use of tranexamic acid in the treatment of postoperative edema and ecchymosis was low.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to systematically examine the role of tranexamic acid in reducing intraoperative blood loss and postoperative edema and ecchymosis among patients undergoing primary rhinoplasty. Five studies were included, most of which were of high methodological quality, with a low degree of bias. The meta-analysis indicated that tranexamic acid has the ability to significantly reduce intraoperative blood loss compared with controls. With a high overall quality of evidence and significant effect size, the use of tranexamic acid should be considered by plastic surgeons when performing rhinoplasties.

Blood loss from surgical procedures is a major issue as the worldwide demand for blood and blood-related products is projected to increase in the coming decades to meet the surgical demands of aging populations.22,23 Both cardiac and noncardiac surgical procedures have been estimated to consume upwards of 15 million U of blood per year in the United States alone, at great financial expense.24,25 The role of tranexamic acid in decreasing surgical blood loss is well known, with its beneficial use being shown in cardiac surgery,26 obstetrics,27 and orthopedic surgery.28,29

A recent review article on the role of tranexamic acid in plastic surgery has highlighted the benefits, doses, and technical considerations for its use in practice.30 In terms of dosing specifics, that article recommends IV doses of 10 mg/kg 3 to 4 times daily based on the drug’s pharmacokinetics, duration of therapeutic influence, and current US Food and Drug Administration guidelines.31,32 When comparing that suggested dosing with the present systematic review and meta-analysis, we found that tranexamic acid dosing varied considerably. Some studies reported single IV dosing and oral regimens during the perioperative period, while others involved a regimen of both perioperative and postoperative doses. A review of the literature indicates that there are no formal guidelines for tranexamic acid dosing in rhinoplasty specifically. Because a proven therapeutic influence is achieved at an IV dose of 10 mg/kg administered 3 to 4 times daily,32 this dosing regimen would be appropriate for use in rhinoplasty.

The results of studies assessing the benefits of tranexamic acid for blood loss among other plastic surgery procedures are comparable to our own. Butz and Geldner33 assessed the role of tranexamic acid among patients undergoing rhytidectomy and observed that rates of hematoma were low (1.4%), and there were no significant hemodynamic complications. The administration of tranexamic acid in their study differed from that in the studies examined in our systematic review and meta-analysis because tranexamic acid–soaked pledgets were applied during surgery and intraoperative blood loss was not specifically measured. Ausen et al34 found that topical application of tranexamic acid, as opposed to the more common IV route, reduced blood loss in women undergoing bilateral reduction mammoplasty. Drain output decreased by 39% at 24 hours after surgery, although there were no significant differences in postoperative pain scores or other surgical complications compared with controls.34 While Ausen et al34 investigated a different elective procedure and method of drug delivery, their results mirror our own and revealed that blood loss may also be reduced after surgery in a more invasive elective cosmetic procedure. In the pediatric literature, a number of high-quality studies35,36,37,38,39,40 investigating the role of tranexamic acid in craniosynostosis procedures have consistently shown that tranexamic acid reduces both intraoperative blood loss and rates of transfusion. The benefits of tranexamic acid in burn surgery are similarly promising41,42; however, more studies are needed before determining causality, dosing regimens, and contraindications in this acutely ill population.43 With the breadth of research among other plastic surgery procedures outside of rhinoplasty also showing positive results, the use of tranexamic acid should be considered by plastic surgeons in a variety of procedures.

The literature investigating the use of tranexamic acid for reduction of postoperative edema and ecchymosis among patients undergoing rhinoplasty is sparse. A recent systematic review of the literature by Ong et al7 reported that other interventions, such as corticosteroids, fibrin sealants, and intraoperative cooling, were able to reduce edema and ecchymosis substantially. Only 1 study that they reviewed specifically investigated the benefits of tranexamic acid, a trial that was also included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis.21 Jalali et al44 completed a randomized study of 70 patients undergoing rhinoplasty and found no difference between patients treated separately with tranexamic acid and dexamethasone on postoperative day 3 in terms of edema and ecchymosis. Among the studies included in the present study, tranexamic acid was superior to controls18 but was not superior to corticosteroids alone or when used in conjunction with corticosteroids.19,20 While not conclusive, our systematic review and meta-analysis reveal a substantial gap in the literature that could be improved by adding postoperative edema and ecchymosis as secondary outcome measures in studies investigating rhinoplasty outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this systematic review and meta-analysis include the use of a wide search strategy to identify relevant articles, the inclusion of high-quality studies, a consistency of the reported results, a low degree of heterogeneity, the ability to conduct a meta-analysis, and a statistically significant effect size. However, there are limitations to this study. First, although our results are similar to those of studies undertaken for other procedures in plastic surgery, they are not generalizable to other surgical specialties or procedures. Second, while our search was broad and comprehensive, we only included articles that were published in English. Third, although the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias is validated by numerous studies, it does not provide a measure of study relevance and does not give a sense of the quality of scientific writing.

Despite the few studies assessing the role of tranexamic acid in decreasing intraoperative bleeding during rhinoplasty, the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that the studies are of high quality and show consistently positive results. These findings are important for several reasons. Tranexamic acid is an inexpensive, safe, effective, and underused agent in plastic surgery. Plastic surgeons should consider using tranexamic acid in their practices in light of the body of clinical evidence demonstrating its utility and benefits.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that tranexamic acid can significantly reduce intraoperative blood loss among patients undergoing primary rhinoplasty. While not conclusive, it also points to a potential benefit of the drug in reducing postoperative edema and ecchymosis. With increasing efforts to conserve blood products, plastic surgeons should consider the use of tranexamic acid in patients undergoing primary elective rhinoplasty.

eTable. Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool

References

- 1.American Society of Plastic Surgeons Plastic surgery statistics report. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2017/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2017.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed Month X, Year.

- 2.Totonchi A, Guyuron B. A randomized, controlled comparison between arnica and steroids in the management of postrhinoplasty ecchymosis and edema. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(1):271-274. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000264397.80585.bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkowitz RL. Commentary on: “Comparison of the Effect of Dexamethasone and Transexamic Acid, Separately or in Combination on Post-rhinoplasty and Edema and Ecchymosis.” Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(1):253-255. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0997-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrotta PL, Snyder EL. Non-infectious complications of transfusion therapy. Blood Rev. 2001;15(2):69-83. doi: 10.1054/blre.2001.0151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ker K, Edwards P, Perel P, Shakur H, Roberts I. Effect of tranexamic acid on surgical bleeding: systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e3054. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, et al. Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:CD001886. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001886.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ong AA, Farhood Z, Kyle AR, Patel KG. Interventions to decrease postoperative edema and ecchymosis after rhinoplasty: a systematic review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(5):1448-1462. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evaniew N, Bhandari M. Cochrane in CORR: topical application of tranexamic acid for the reduction of bleeding (review). Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475(1):21-26. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5112-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillette BP, DeSimone LJ, Trousdale RT, Pagnano MW, Sierra RJ. Low risk of thromboembolic complications with tranexamic acid after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(1):150-154. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2488-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goobie SM, Cladis FP, Glover CD, et al. ; Pediatric Craniofacial Collaborative Group . Safety of antifibrinolytics in cranial vault reconstructive surgery: a report from the Pediatric Craniofacial Collaborative Group. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017;27(3):271-281. doi: 10.1111/pan.13076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishijima DK, Monuteaux MC, Faraoni D, et al. Tranexamic acid use in United States children’s hospitals. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(6):868-874.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):W65-W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Medical Association World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen A, Mahabir RC. An update on the level of evidence for plastic surgery research published in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(7):e798. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. ; Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines, 3: rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401-406. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beikaei M, Ghazipour A, Derakhshande V, Saki N, Nikakhlagh S. Evaluating the effect of intravenous tranexamic acid on intraoperative bleeding during elective rhinoplasty. Biomed Pharm J. 2015;8(special edition):753-759. doi: 10.13005/bpj/779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eftekharian HR, Rajabzadeh Z. The efficacy of preoperative oral tranexamic acid on intraoperative bleeding during rhinoplasty. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(1):97-100. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghavimi MA, Taheri Talesh K, Ghoreishizadeh A, Chavoshzadeh MA, Zarandi A. Efficacy of tranexamic acid on side effects of rhinoplasty: a randomized double-blind study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45(6):897-902. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehdizadeh M, Ghassemi A, Khakzad M, et al. Comparison of the effect of dexamethasone and tranexamic acid, separately or in combination on post-rhinoplasty edema and ecchymosis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018;42(1):246-252. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0969-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakallioğlu Ö, Polat C, Soylu E, Düzer S, Orhan İ, Akyiğit A. The efficacy of tranexamic acid and corticosteroid on edema and ecchymosis in septorhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74(4):392-396. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182a1e527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson LM, Devine DV. Challenges in the management of the blood supply. Lancet. 2013;381(9880):1866-1875. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60631-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seifried E, Klueter H, Weidmann C, et al. How much blood is needed? Vox Sang. 2011;100(1):10-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitaker B, Rajbhandary S, Kleinman S, Harris A, Kamani N. Trends in United States blood collection and transfusion: results from the 2013 AABB Blood Collection, Utilization, and Patient Blood Management Survey. Transfusion. 2016;56(9):2173-2183. doi: 10.1111/trf.13676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shander A, Hofmann A, Ozawa S, Theusinger OM, Gombotz H, Spahn DR. Activity-based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion. 2010;50(4):753-765. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myles PS, Smith JA, Forbes A, et al. ; ATACAS Investigators of the ANZCA Clinical Trials Network . Tranexamic acid in patients undergoing coronary-artery surgery. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(2):136-148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shakur H, Roberts I, Fawole B, et al. ; WOMAN Trial Collaborators . Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017;389(10084):2104]. Lancet. 2017;389(10084):2105-2116. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30638-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarda P, Alshryda S. Topical usage of tranexamic acid: comparative analysis in patients with bilateral total knee replacement. EC Orthop. 2017;7.4:182-187. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zufferey PJ, Lanoiselée J, Chapelle C, et al. ; investigators of the PeriOpeRative Tranexamic acid in hip arthrOplasty (PORTO) Study . Intravenous tranexamic acid bolus plus infusion is not more effective than a single bolus in primary hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(3):413-422. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohrich RJ, Cho MJ. The role of tranexamic acid in plastic surgery: review and technical considerations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(2):507-515. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200108000-00035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersson L, Nilsoon IM, Colleen S, Granstrand B, Melander B. Role of urokinase and tissue activator in sustaining bleeding and the management thereof with EACA and AMCA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;146(2):642-658. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb20322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cyklokapron Tranexamic Acid Injection New York, NY: Pfizer Injectables; 2017. http://labeling.pfizer.com/showlabeling.aspx?id=556. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- 33.Butz DR, Geldner PD. The use of tranexamic acid in rhytidectomy patients. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(5):e716. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ausen K, Fossmark R, Spigset O, Pleym H. Randomized clinical trial of topical tranexamic acid after reduction mammoplasty. Br J Surg. 2015;102(11):1348-1353. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goobie SM, Meier PM, Pereira LM, et al. Efficacy of tranexamic acid in pediatric craniosynostosis surgery: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(4):862-871. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210fd8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy GR, Glass GE, Jain A. The efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in cranio-maxillofacial and plastic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(2):374-379. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000002250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martin JP, Wang JS, Hanna KR, Stovall MM, Lin KY. Use of tranexamic acid in craniosynostosis surgery. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2015;23(4):247-251. doi: 10.1177/229255031502300413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crantford JC, Wood BC, Claiborne JR, et al. Evaluating the safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid administration in pediatric cranial vault reconstruction. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(1):104-107. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White N, Bayliss S, Moore D. Systematic review of interventions for minimizing perioperative blood transfusion for surgery for craniosynostosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26(1):26-36. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dadure C, Sauter M, Bringuier S, et al. Intraoperative tranexamic acid reduces blood transfusion in children undergoing craniosynostosis surgery: a randomized double-blind study. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(4):856-861. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318210f9e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tang YM, Chapman TW, Brooks P. Use of tranexamic acid to reduce bleeding in burns surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(5):684-686. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Domínguez A, Alsina E, Landín L, García-Miguel JF, Casado C, Gilsanz F. Transfusion requirements in burn patients undergoing primary wound excision: effect of tranexamic acid. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83(4):353-360. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.16.10992-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walsh K, Nikkhah D, Dheansa B. What is the evidence for tranexamic acid in burns? Burns. 2014;40(5):1055-1057. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2014.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jalali MM, Moosavi S, Fatemi S, Banan R. Comparison between dexamethasone and tranexamic acid on postoperative edema and ecchymosis after rhinoplasty operation [in Arabic]. Guilan University Med Sci. 2012;21(81):72-77. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool