Abstract

The transplant community is divided regarding whether substitution with generic immunosuppressants is appropriate for organ transplant recipients. We estimated the rate of uptake over time of generic immunosuppressants using US Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event (PDE) and Colorado pharmacy claims (including both Part D and non-Part D) data from 2008 to 2013. Data from 26 070 kidney, 15 548 liver, and 6685 heart recipients from Part D, and 1138 kidney and 389 liver recipients from Colorado were analyzed. The proportions of patients with PDEs or claims for generic and brand-name tacrolimus or mycophenolate mofetil were calculated over time by transplanted organ and drug. Among Part D kidney, liver, and heart beneficiaries, the proportion dispensed generic tacrolimus reached 50%−56% at 1 year after first generic approval and 78%−81% by December 2013. The proportion dispensed generic mycophenolate mofetil reached 70%−73% at 1 year after generic market entry and 88%−90% by December 2013. There was wide interstate variability in generic uptake, with faster uptake in Colorado compared with most other states. Overall, generic substitution for tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil for organ transplant recipients increased rapidly following first availability, and utilization of generic immunosuppressants exceeded that of brand-name products within a year of market entry.

Keywords: brand-name, generic, immunosuppressant, generic drug substitution, kidney transplantation, liver transplantation/hepatology, heart transplantation, organ transplantation in general, health services and outcomes research

1 |. INTRODUCTION

To reduce the risk of graft rejection and loss after organ transplantation, transplant recipients must have access to immunosuppressive medications (ISMs). ISM costs can be a substantial burden for transplant patients, potentially limiting access and increasing nonadherence.1,2 The use of therapeutically equivalent generic products can reduce recipients’ and payers’ financial burdens. However, the transplant community has expressed concerns about generic substitution for brand-name ISMs and the substitution of one generic product for another.2–7 In addition, patients may not believe generic ISMs are equivalent to their brand-name counterparts and may not be receptive to payer-driven generic substitution.2,8 Previous generic vs brand-name ISM comparison studies are limited by small sample sizes, retrospective designs, inclusion of only healthy volunteers, or inconsistent results across studies.6,9–13

Results from bioequivalence studies and expected cost savings associated with generic ISMs have led several US and international professional transplant societies to issue guidelines advocating for generic ISM substitution.3,14,15 If all prescription requirements are met, generic substitution can even be carried out without prescriber or patient input in some states.6,16–18 Generic-for-brand or generic-for-generic substitutions can also confuse patients. Different versions of a drug can have different appearances, which may lead to increased risk of medication errors and non-adherence.6 Partly due to these concerns, the aforementioned guidelines all recommend that generic substitution of ISMs only be implemented with frequent patient monitoring, patient education on differences between products, and caution under certain clinical conditions.

The most widely used ISMs by US organ transplant recipients are tacrolimus (TAC) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF).19 The first generic versions of MMF and TAC were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in July 2008 and August 2009, respectively. A 2013 Drug Trend Report from a prescription benefit plan provider estimated generic mycophenolate (did not specify MMF or mycophenolate sodium [MPS]) and TAC to capture 33.5% and 30.7% of the total market share of all transplant medications, compared to 7.4% for brand-name mycophenolic acid and 7.2% for brand-name TAC.20 However, there is little additional information on the penetration of generic TAC and MMF or on trends in use over time.

In this study, we used the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), national Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Events (PDEs), and the Colorado All-Payer Claims Database (CO-APCD) to describe dispensing patterns for generic and brand-name ISMs from 2008 to 2013 for kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients. Our primary objective was to describe the trajectory of uptake of generic TAC and MMF over time in a national sample of transplant recipients. Our secondary objective was to investigate state-by-state variation in uptake of generic ISMs.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design and data sources

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, a national registry of organ transplantation data, was used to identify all pediatric and adult kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients in the United States between 1987 and 2013. These data were linked to national Medicare Part D PDE data to identify TAC and MMF prescriptions filled between January 2008 and December 2013 for transplant recipients whose ISMs were covered by Part D. The prescription period from 2008 to 2013 was chosen to correspond to the years after FDA approvals for the first generic MMF and TAC products. Part D data were used because they include the National Drug Code (NDC) for ISMs, which differentiates between generic and brandname products. Part B (another source of coverage for ISMs) data were not examined because they do not include the NDCs necessary to distinguish generic from brand-name PDEs. Eligibility for ISM coverage by Medicare Part B vs Medicare Part D is detailed in Supplement I.

SRTR data were also linked to the CO-APCD to obtain claims for prescription ISMs filled in Colorado from January 2009 through September 2014. The CO-APCD was used because it contains NDCs for claims from both Part D and non-Part D patients, including most claims paid by commercial insurance carriers, Medicare, Medicare Advantage plans, and Medicaid for Colorado residents since 2009.

Analyses were carried out separately for Part D and CO-APCD data by organ and drug type. In Part D, TAC and MMF PDEs for kidney, liver, and heart were analyzed. In the CO-APCD, only liver TAC and kidney TAC and MMF claims were analyzed due to small sample sizes of the other organ-drug combinations.

2.2 |. Study sample

Patients were eligible for primary analyses if they (1) received a single-organ kidney, liver, or heart transplant (ie, simultaneous multiple organ transplants were excluded) between 1987 and 2013 and maintained graft function for 30 days following transplantation; (2) had graft function on January 1, 2008 for those who received their transplant before 2008; and (3) had at least 1 posttransplant TAC or MMF PDE or pharmacy claim during the study period. Graft function was defined as the absence of all-cause graft failure, including repeat transplantation or death for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, and additionally return to dialysis for kidney recipients.

2.3 |. Outcome variables

Our primary outcome was brand-name or generic PDEs or pharmacy claims for TAC and MMF. As our focus was uptake of generic ISMs among transplant recipients, we did not assess conversions from generic to brand or between different types of generic ISM products.

Mycophenolate sodium is used as an alternative to MMF in some transplant recipients; however, MPS was not included in the main analysis because the first MPS generic application was approved by the FDA late in our study period (2012).

2.4 |. Independent variables

Due to our interest in adoption rates of generic ISMs over time, our primary independent variable was calendar month. In additional analyses, we stratified national Medicare Part D PDE data by the state where transplants occurred and assessed associations between generic uptake and state pharmacy laws. For the latter, we used the Survey of Pharmacy Laws to categorize states as having mandatory vs permissive generic substitution laws and as requiring patient consent or notification of generic substitution or not.18 Colorado in particular required patient consent and did not mandate generic substitution. Additional independent variables were explored in sensitivity analyses (Supplement III).

2.5 |. Statistical analysis

For each analysis, we calculated the percentage of patients dispensed brand-name or generic ISMs by calendar month for the entire study period. Patients dispensed both brand-name and generic products in the same month were counted as one half for each. For each percentage, a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using the Wilson score method.21 Reference lines in the graphs indicate approval dates of generic products to facilitate interpretation. FDA approvals for different generic ISM dosage forms or strengths under the same application number or application holder were grouped and the earliest generic approval date was used.

Using Part D PDEs, we also calculated percentages of ISM prescriptions filled with generic products over time for kidney and liver recipients in each US state and Washington, DC. States with less than 20 transplant patients prescribed the ISM during a given month were excluded from analysis for that month due to imprecision of percentage estimates. We did not perform this analysis for heart recipients because half or more states had less than 20 patients during most calendar months.

To evaluate whether yearly state-level uptake of generic ISM was associated with differences in state laws governing generic substitution, we used linear generalized estimating equation models with sandwich-type standard error estimators to account for correlations among years within states, adjusting for calendar year. States with less than 20 patients in a year were excluded from that year’s analyses.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

3 |. RESULTS

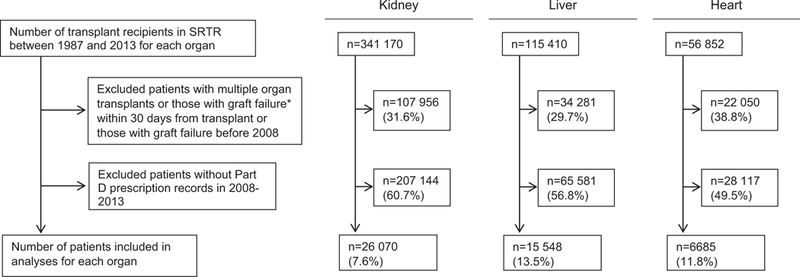

There were 26 070 kidney, 15 548 liver, and 6685 heart transplant recipients enrolled in Part D who met study eligibility criteria (Figure 1), accounting for 7.6%, 13.5%, and 11.8% of all kidney, liver, and heart transplant recipients since 1987, respectively. These recipients were mostly male, white, aged 50–64 years (Table 1), and generally older and received their transplant less recently than the transplant population not enrolled in Part D (Supplement II). In the CO-APCD, 1138 kidney and 389 liver recipients were included in the analysis and were similar to the Part D cohort (see Supplement II for additional demographic and clinical data on both cohorts).

FIGURE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion of transplant recipients in Medicare Part D data. These charts show the total number of transplant recipients and the numbers excluded from analyses because of graft failure within 30 days from transplant, multiorgan transplantation, graft failure before 2008 (the start of our data period), or absence of Part D PDEs, and the number of subjects included in the final analyses by each organ type. The denominator for each percentage is the number of transplant recipients recorded in the SRTR during the study period (top box). *Graft failure was defined as the earliest of graft failure indicator from SRTR, re-transplantation, or death. PDEs, Prescription Drug Events; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

TABLE 1.

Descriptive statistics of transplant recipients by data source and organ type

| Data source Organ type |

Medicare part D |

Colorado APCD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kidney | Liver | Heart | Kidney | Liver | |

| Number of transplant recipientsa | 26 070 | 15 548 | 6685 | 1138 | 389 |

| Number of transplants | 26 170 | 15 622 | 6705 | 1147 | 389 |

| Year of transplantd | |||||

| 1987–1990 | 0.8% (208) | 1.4% (210) | 1.8% (121) | 3.3% (37) | 5.9% (23) |

| 1991–1995 | 3.6% (944) | 6.3% (979) | 7.7% (517) | ||

| 1996–2000 | 15.3% (3978) | 16.7% (2602) | 19.6% (1307) | 9.7% (110) | 12.3% (48) |

| 2001–2005 | 31.4% (8195) | 29.4% (4576) | 28.4% (1899) | 23.6% (268) | 21.3% (83) |

| 2006–2010 | 39.3% (10 242) | 36.0% (5605) | 33.2% (2221) | 37.6% (428) | 33.2% (129) |

| 2011–2013 | 9.6% (2503) | 10.1% (1576) | 9.3% (620) | 25.9% (295) | 27.2% (106) |

| Male | 57.2% (14 925) | 60.6% (9429) | 72.7% (4863) | 56.2% (639) | 62.0% (241) |

| Racee | |||||

| White | 51.9% (13 524) | 71.7% (11 151) | 72.2% (4827) | 61.9% (704) | 71.0% (276) |

| Black | 24.9% (6493) | 8.5% (1318) | 16.9% (1128) | 10.6% (121) | 3.6% (14) |

| Hispanic | 16.0% (4179) | 14.6% (2272) | 8.0% (536) | 23.5% (267) | 21.3% (83) |

| Asian/Other | 7.2% (1873) | 5.2% (802) | 2.9% (194) | 4.0% (46) | 4.1% (16) |

| Age, years | |||||

| Median (IQR) | 52 (39–61) | 54 (48–60) | 54 (45–60) | 47 (33–58) | 50 (39–57) |

| <18 | 3.8% (993) | 0.9% (143) | 1.6% (106) | 6.8% (77) | 6.7% (26) |

| 18–34 | 14.4% (3760) | 5.2% (809) | 10.4% (697) | 19.7% (224) | 13.6% (53) |

| 35–49 | 25.3% (6587) | 24.4% (3789) | 23.1% (1546) | 28.6% (326) | 28.8% (112) |

| 50–64 | 42.7% (11 129) | 61.5% (9566) | 57.1% (3818) | 32.5% (370) | 46.5% (181) |

| ≥65 | 13.8% (3601) | 8.0% (1241) | 7.7% (518) | 12.4% (141) | 4.4% (17) |

| BMI, kg/m2e | |||||

| <18.5 | 4.5% (1026) | 2.5% (361) | 4.1% (257) | 8.1% (87) | 7.5% (29) |

| ≥18.5 to <25.0 | 35.3% (8056) | 29.7% (4276) | 37.3% (2365) | 37.7% (407) | 37.9% (146) |

| ≥25.0 to <30.0 | 32.1% (7317) | 35.2% (5071) | 36.9% (2340) | 31.7% (342) | 32.2% (124) |

| ≥30.0 | 28.1% (6416) | 32.7% (4713) | 21.7% (1376) | 22.6% (244) | 22.3% (86) |

| Transplant typec,e | |||||

| Donation after circulatory death | 5.1% (1297) | 3.1% (454) | 6.6% (74) | 3.7% (14) | |

| Donation after brain death | 57.0% (14 588) | 93.5% (13 902) | 49.5% (555) | 89.8% (336) | |

| Living related donation | 25.7% (6583) | 2.5% (379) | 25.9% (290) | 6.4% (24) | |

| Living unrelated donation | 12.2% (3124) | 0.9% (137) | 18.0% (202) | ||

| Previous transplant of the same organ type | 10.9% (2850) | 5.6% (867) | 2.1% (143) | 9.2% (105) | 2.6% (10) |

| Number of HLA mismatches: 1-6 vs 0e | 87.8% (22 515) | 88.9% (1005) | |||

| Recipient diagnosis (kidney)e | |||||

| Diabetes | 22.5% (5813) | 21.5% (243) | |||

| Hypertension | 22.2% (5743) | 13.1% (148) | |||

| Glomerulonephritis | 25.4% (6559) | 32.3% (365) | |||

| Cystic kidney disease | 8.8% (2280) | 11.2% (127) | |||

| Other | 21.1% (5446) | 21.9% (248) | |||

| Recipient diagnosis (liver)b,e | |||||

| Acute hepatic necrosis | 5.9% (919) | 4.4% (17) | |||

| Cholestatic liver disease/cirrhosis | 12.7% (1969) | 17.5% (68) | |||

| Noncholestatic cirrhosis | 50.0% (7776) | 46.3% (180) | |||

| Hepatitis C | 40.3% (6271) | 38.3% (149) | |||

| Malignant neoplasm | 17.6% (2744) | 23.4% (91) | |||

| Metabolic disease | 3.7% (572) | 3.6% (14) | |||

| Other liver disease | 14.6% (2267) | 9.0% (35) | |||

| Recipient diagnosis (heart)e | |||||

| Coronary artery disease | 42.6% (2845) | ||||

| Cardiomyopathy | 50.0% (3335) | ||||

| Congenital/valvular/other | 7.4% (496) | ||||

| Ventricular assist device (heart)e | 38.1% (1710) | ||||

APCD, All-Payer Claims Database; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IQR, interquartile range.

For Colorado liver patients, only those with tacrolimus claims were included.

Diagnoses for liver transplant recipients are based on both primary and secondary diagnoses and are not mutually exclusive. Each liver recipient can have 1 or 2 diagnoses; therefore, percentages will not sum to 100%.

For Colorado APCD liver patients, living related and unrelated donations were combined to suppress cells with n < 10.

For Colorado APCD patients, transplant years 1987 to 1990 and 1991 to 1995 were combined into 1 group to suppress cells with n < 10.

Missing for at most 5% of patients, except BMI missing for 7% and 12% of Medicare part D liver and kidney patients, respectively, and ventricular assist device missing for 33% of Medicare part D heart patients.

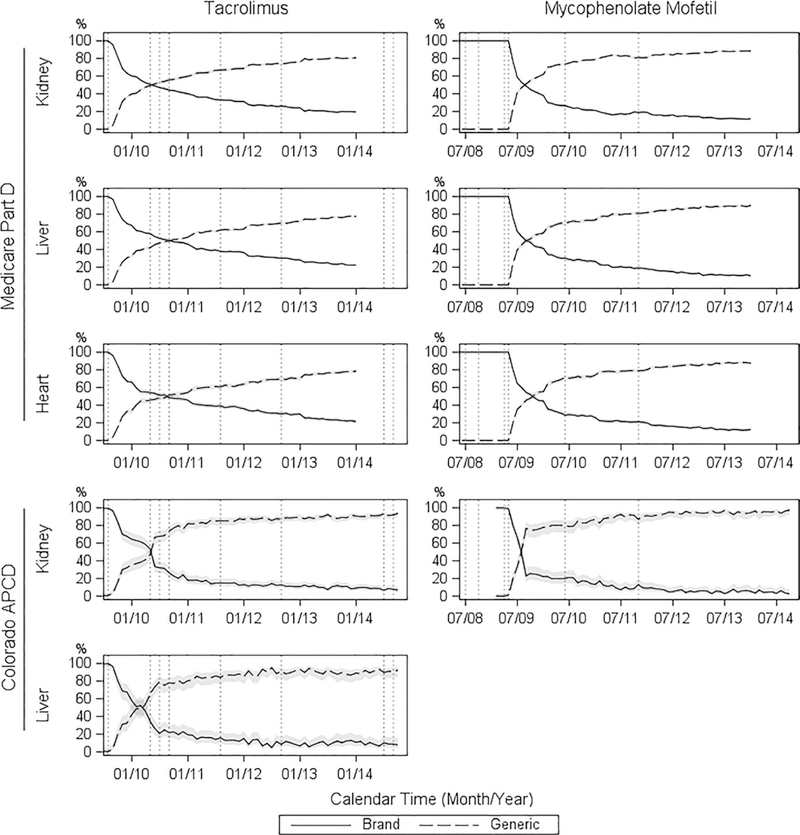

Among Part D beneficiaries with PDEs for TAC (generic or brand name), the proportion of kidney, liver, and heart recipients with PDEs for generic TAC reached 56%, 50%, and 51%, respectively, at 1 year after approval of the first generic TAC product (Figure 2). In contrast, generic MMF was unavailable until 9 months after the approval date of the first generic product. However, after 1 year of entering the market, the proportion dispensed generic MMFs (out of all MMF PDEs) increased to 73%, 70%, and 71% for kidney, liver, and heart recipients, respectively. By December 2013, across organs, 78–81% and 88–90% of recipients with PDEs for TAC and MMF were dispensed the generic products, respectively. For both ISM types, adoption patterns for generic products were similar across organ type.

FIGURE 2.

Percent of patients dispensed generic vs brand-name immunosuppressants over time. Each vertical line marks the date of FDA US Food and Drug Administration approval of a generic tacrolimus or mycophenolate mofetil product. The 95% confidence intervals for the percentages are displayed as gray bands. APCD, All-Payer Claims Database

In the CO-APCD, 74% and 78% of kidney and liver recipients were dispensed generic TAC at 1 year after first generic approval, respectively; and 80% of kidney recipients were dispensed generic MMF at 1 year after first generic market entry. By December 2013, 90% and 89% of kidney and liver recipients were dispensed generic TAC, respectively; and 95% of kidney recipients were dispensed generic MMF.

Results from sensitivity analyses showed that brand-name ISM prescriptions were more likely to have dispense as written (DAW) codes that precluded generic substitution, including prescriber and patient preferences, while other factors did not appear to affect generic uptake (Supplement III).

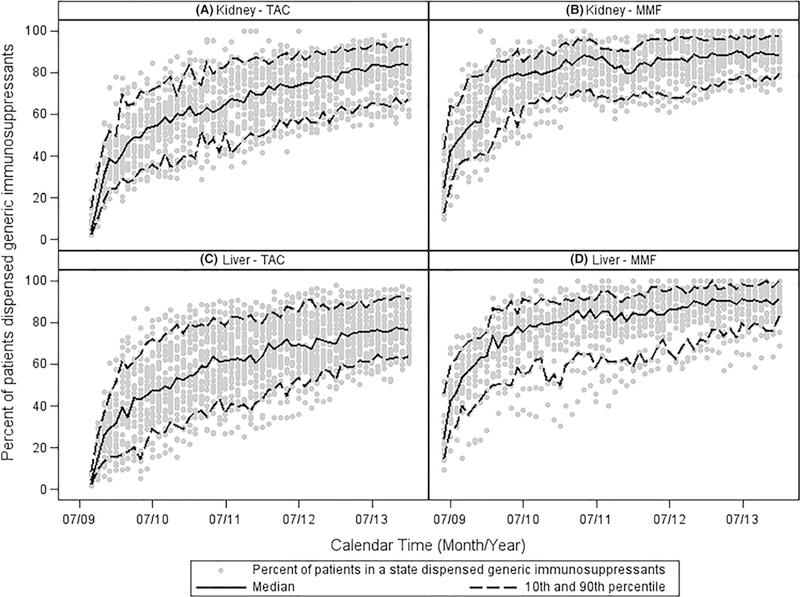

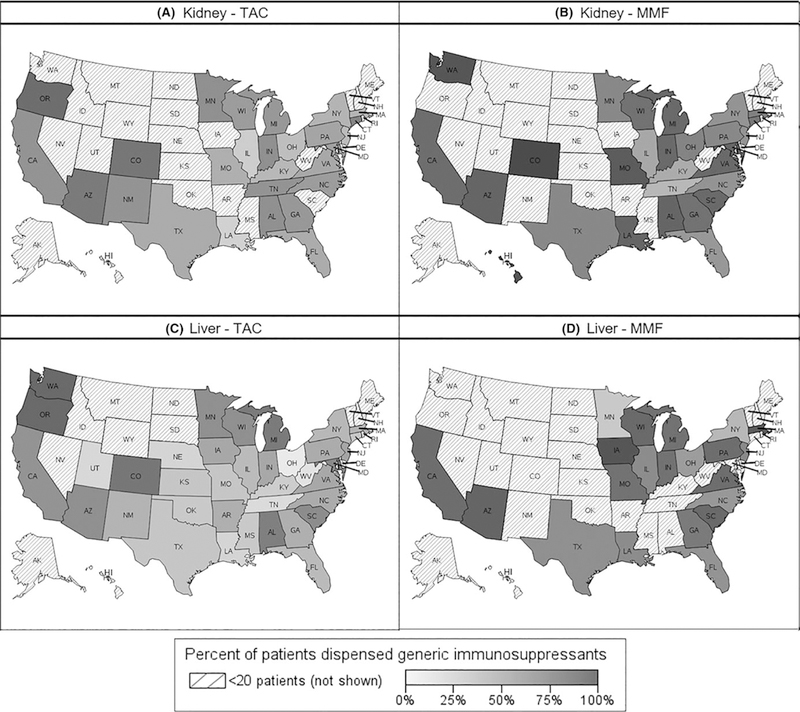

Part D PDE analyses by state showed large interstate variability in uptake of generic ISMs (Figure 3). At 1 year after first generic TAC approval, the range between the 10th and 90th percentiles in uptake across states was 34 and 47 percentage points among kidney and liver recipients, respectively. Similarly, the range at 1 year after first generic MMF entry was 37 and 26 percentage points among kidney and liver recipients, respectively. Additionally, the percentage of generic ISMs dispensed in December 2013 also varied by state. The range between the 10th and 90th percentiles across states was 27 and 28 percentage points for TAC and 18 and 17 percentage points for MMF, among kidney and liver recipients, respectively. States with the highest percentages of generic TAC ISMs dispensed at 1 year after generic approval included Colorado, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington (Figure 4). States with the highest percentages of generic MMF ISMs dispensed at 1 year after generic market entry included Colorado, Washington, Hawaii, and Missouri. No clear association between patient consent regulations and generic uptake was detected (Figure S4); and mandatory generic substitution, although not reaching statistical significance, was weakly associated with lower generic uptake.

FIGURE 3.

State-level variability in uptake of generic tacrolimus (TAC) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Panels A and B show the percent uptake of generic TAC or MMF among kidney transplant recipients. Panels C and D show the percent uptake of generic TAC or MMF among liver transplant recipients. Data from states with fewer than 20 kidney or liver transplant recipients with TAC or MMF prescription drug events in the Medicare Part D database are not shown

FIGURE 4.

Percent of patients dispensed generic immunosuppressants at 1 year after national generic approval and market entry. Panels A and B show percent uptake of generic tacrolimus (TAC) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) among kidney transplant recipients. Panels C and D show percent uptake of generic TAC and MMF among liver transplant recipients. Data from states with fewer than 20 kidney or liver transplant recipients with TAC or MMF prescription drug events in the Medicare Part D database are not shown

4. |. DISCUSSION

Post-FDA approval, the proportion of patients with PDEs for generic ISMs increased rapidly and exceeded those with PDEs for brand-name ISMs within 1 year. For TAC, generic uptake began soon after the first FDA approval of a generic product while generic MMF uptake did not begin until after the approval of several generic versions. This difference can be explained by the timing of brand-name patent expiration relative to FDA approval dates of these generic products. Expiration of the US patent for brandname TAC (Prograf, Patent No. 4894366) preceded the first FDA approval date for generic TAC by 1 year, allowing generic TAC uptake to begin immediately following FDA approval. In contrast, the first FDA approval dates for generic MMF were in 2008 but the patent for brand-name MMF (CellCept, Patent No. 4753935) did not expire until May 3, 2009. Therefore, the first generic MMF drugs were not dispensed until 2009.

Faster uptake of generic ISMs was observed in the CO-APCD compared with national averages from Part D. This result was consistent with our Part D state-level analyses, which showed different rates of generic ISM uptake by state. Our results did not support our hypothesis that differences in state regulations on dispensing of generic medications might explain this interstate variability. In Colorado specifically, state pharmacy law requires patient consent for generic substitution and does not mandate generic substitution (ie, generic substitution is permissive), yet Colorado was one of the states with the highest generic ISM uptake rates. Differences across states in socioeconomic status of organ transplant recipients, access to health care, and payer behavior could also have influenced the generic uptake rates in Colorado.

Market penetration of generic MMFs at 1 year was comparable to averages observed among other medications with first generic entry in 2008 or 2009, while generic TAC uptake was more gradual.22 This difference may reflect some practitioners’ initial hesitancy to allow patients to switch to generic TAC given that TAC is a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) medication,2,23 whereas MMF is not. NTI status implies greater risk of adverse clinical consequences from too high or too low drug concentrations.2,7,17,24 Thus, until therapeutic equivalency is confirmed in clinical practice, there may be more apprehension about the efficacy of generic versions of NTI medications such as TAC.2,25

Our study found that uptake of generic ISMs was largely influenced by generic market entry and calendar time. Adoption of generic ISMs did not appear to depend on time elapsed since transplant. The uptake patterns for each generic ISM was consistent across types of transplanted organs.

Additionally, market forces may have influenced the uptake of generic ISMs. For example, by adding the generic product to its formulary with lower patient copayments, payers may incentivize generic ISM use.22 Pharmaceutical industry practices such as patient copay assistance programs (data unavailable) may also influence generic uptake.26,27 Furthermore, prescriber practices and patient preferences appear to have affected brand-name vs generic prescriptions substantially, as observed from our sensitivity analysis of DAW status of PDEs for brand-name ISMs. Generic substitution at the pharmacy is not mandatory in all states;18 thus it is possible that pharmacy practices (unavailable in our data) may also affect selection of generic products.

Introduction of generic drug products is expected to reduce costs for payers and patients, potentially increasing access and adherence. Assessment of these benefits in transplantation necessitates exploration of the longitudinal use of generic ISMs, which has not previously been reported. As more transplant recipients use generic ISMs, the potential cost savings to both payers and patients may increase. Since ISM costs paid by patients may exceed $500/month7 and overall ISM costs may exceed $4000/month,2 the magnitude of the potential cost savings could be substantial.

Our study has several strengths, including use of multiple data sources with monthly data spanning multiple years after the introduction of generic ISMs. The CO-APCD includes transplant recipients covered by a large variety of payers. The Part D data represent a large national sample of Medicare beneficiaries. Using both data sources and sensitivity analyses, we were able to confirm robustness of results.

Our study also has limitations. Since we only analyzed data from CO-APCD and Part D, generalizability of results to the larger US transplant population or the overall Medicare transplant population is uncertain. Our analysis of the Medicare population was limited to Part D PDEs, since the NDCs necessary to differentiate between brand-name and generic products are unavailable in Part B. Thus, although Medicare Part B is a common payer for ISMs among transplant recipients, particularly kidney recipients during the first 3 years posttransplant, Part B data cannot be used to analyze uptake of generic ISMs. Given that Medicare Part D plans often encourage use of generic products28,29 while Medicare Part B may not,30 it is possible that our results are only applicable to Part D beneficiaries rather than the entire Medicare population.

In addition, we did not have data on adherence, limiting interpretation of our results to dispensing of generics rather than actual use. Finally, only a portion of each patient’s follow-up period, particularly within the Part D database, was accounted for in our data. Missing data could have several explanations, including (1) patients’ ISM prescriptions were paid by sources not included in the available databases; (2) patients switched to different types of ISMs or stopped using the classes of ISMs analyzed; (3) patients had decreases in dosage or accumulated a surplus of ISMs that allowed them to use existing prescriptions for longer than the original days’ supply; or (4) incompleteness in data acquisition. However, it is unlikely that these scenarios would introduce bias in our results, because none of them would be expected to occur at a different rate over time for brand-name compared with generic ISMs.

Our study demonstrates rapid uptake and high proportions of dispensed generic TAC and MMF, as well as wide interstate variability in generic ISM penetration. The impetus of generic adoption is presumably cost savings to both patients and payers. Research is currently in progress to assess changes in ISM costs for transplant recipients following the introduction of generic ISMs. Further study into the potential relationship between generic uptake and graft outcomes is also warranted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this research was made possible by the US Food and Drug Administration through grant 1U01FD005274-01. Views expressed in written materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the US Food and Drug Administration or the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the United States Government. The Colorado All Payer Claims Database (CO-APCD) is administered by the nonprofit Center for Improving Value in Health Care (CIVHC) in Denver, Colorado. This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), US Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. This study was deemed exempt from the need for IRB review.

Funding information

Food and Drug Administration, Grant/Award Number: 1U01FD005274-01

AL reports grants from US Food and Drug Administration, during the conduct of the study; and serves on a Data and Safety Monitoring Board for a study of a biological agent being developed by a company that also manufactures one of the pharmaceutical agents reported on in this manuscript, outside the submitted work. CAB, MF, MH, JP, AS, QL, PS, RB, SG, AS, JZ, and MT report grants from the US Food and Drug Administration during the conduct of the study.

Abbreviations:

- APCD

All-Payer Claims Database

- FDA

US Food and Drug Administration

- ISMs

immunosuppressive medications

- MMF

mycophenolate mofetil

- MPS

mycophenolate sodium

- NDC

National Drug Code

- NTI

narrow therapeutic index

- PDE

Prescription Drug Event

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

- TAC

tacrolimus

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gordon EL, Prohaska TR, Sehgal AR. The financial impact of immunosuppressant expenses on new kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:738–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EI Hajj S, Kim M, Phillips K, Gabardi S. Generic immunosuppression in transplantation: current evidence and controversial issues. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2015;11:659–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alloway RR, Isaacs R, Lake K, et al. Report of the American Society of Transplantation conference on immunosuppressive drugs and the use of generic immunosuppressants. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1211–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensor CR, Trofe-Clark J, Gabardi S, McDevitt-Potter LM, Shullo MA. Generic maintenance immunosuppression in solid organ transplant recipients. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:1111–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molnar AA, Fergusson D, Tsampalieros AK, et al. Generic immune-suppression in solid organ transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Gelder T What is the future of generics in transplantation? Transplantation. 2015;99:2269–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taube D, Jones G, O’Beirne J, et al. Generic tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2014;28:623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulbert AL, Pilch NA, Taber DJ, Chavin KD, Baliga PK. Generic immunosuppression: deciphering the message our patients are receiving. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klintmalm GB. Immunosuppression, generic drugs and the FDA. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1765–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutkowski B, Bzoma B, Debska-Slizien A, Chamienia A. Generic formulation of mycophenolate mofetil (Myfenax) in de novo renal transplant recipients: results of 12-month observation. Transplant Proc. 2014;46:2683–2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Connor A, Prowse A, Newell P, Rowe PA. A single-centre comparison of the clinical outcomes at 6 months of renal transplant recipients administered Adoport® or Prograf® preparations of tacrolimus. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6:21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sunder-Plassmann G, Reinke P, Rath T, et al. Comparative pharma-cokinetic study of two mycophenolate mofetil formulations in stable kidney transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2012;25:680–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Momper JD, Ridenour TD, Schonder KS, Shapiro R, Humar A, Venkataramanan R. The impact of conversion from Prograf to generic tacrolimus in liver and kidney transplant recipients with stable graft function. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1861–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uber PA, Ross HJ, Zuckermann AO, et al. Generic drug immunosuppression in thoracic transplantation: an ISHLT educational advisory. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:655–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasiske BL, Zeier MG, Chapman JR, et al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients: a summary. Kidney Int. 2010;77:299–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lionberger R, Jiang W, Huang SM, Geba G. Confidence in generic drug substitution. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:438–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popat R Generic immunosuppression: to embrace or dismiss? J Renal Nursing. 2011;3:194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Survey of pharmacy law. 2009–2013. https://nabp.pharmacy/publications-reports/publications/survey-of-pharmacy-law/. Accessed July 17, 2017.

- 19.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). OPTN/SRTR 2015 annual data report. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The express scripts 2013 drug trend report. Published April 2014. http://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/drug-trend-report/previous-reports. Accessed February 28, 2017.

- 21.Wilson EB. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am Stat Assoc. 1927;22:209–212. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grabowski H, Long G, Mortimer R, Boyo A. Updated trends in US brand-name and generic drug competition. J Med Econ. 2016;19:836–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarpatwari A, Lee MP, Gagne JJ, et al. Generic versions of narrow therapeutic index drugs: a national survey of pharmacists’ substitution beliefs and practices [published online ahead of print November 22, 2017]. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 10.1002/cpt.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee RA, Gabardi S. Current trends in immunosuppressive therapies for renal transplant recipients. Am J Health-System Pharm. 2012;69:1961–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips K, Reddy P, Gabardi S. Is there evidence to support brand to generic interchange of the mycophenolic acid products? J Pharm Pract. 2017;30:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Coalition on Health Care (NCHC), “Seniors’ awareness and use of prescription co-pay coupons in medicare,” survey. March 26–30, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ross JS, Kesselheim AS. Prescription-drug coupons-no such thing as a free lunch. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1188–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang Y, Gellad WF, Men A, Donohue JM. Impact of medicare part D plan features on use of generic drugs. Med Care. 2014;52(6): 541–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levinson DR. Inspector general department of health and human services Office of Inspector General. Generic Drug Utilization in the Medicare Part D Program; November 2007; OEI-05–07-00130. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-07-00130.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Certner DM. Legislative Counsel & Legislative Policy Director, Government Affairs, American Association of Retired Persons (Letter) Medicare Program: Part B Drug Payment Model CMS- 1670-P. AARP; https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/politics/advocacy/2016/05/aarp-part-b-drug-payment-payment-model-may-09-2016.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2017. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.