Abstract

Objective

Direct-acting antivirals have opened an opportunity for controlling hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in Pakistan, where 10% of the global infection burden is found. We aimed to evaluate the implications of five treatment programme scenarios for HCV treatment as prevention (HCV-TasP) in Pakistan.

Design

An age-structured mathematical model was used to evaluate programme impact using epidemiological and programme indicators.

Setting

Total Pakistan population.

Participants

Total Pakistan HCV-infected population.

Interventions

HCV treatment programme scenarios from 2018 up to 2030.

Results

By 2030 across the five HCV-TasP scenarios, 0.6–7.3 million treatments were administered, treatment coverage reached between 3.7% and 98.7%, prevalence of chronic infection reached 2.4%–0.03%, incidence reduction ranged between 41% and 99%, program-attributed reduction in incidence rate ranged between 7.2% and 98.5% and number of averted infections ranged between 126 221 and 750 547. Annual incidence rate reduction in the first decade of the programme was around 6%–18%. Number of treatments needed to prevent one new infection ranged between 4.7–9.8, at a drug cost of about US$900. Cost of the programme by 2030, in the most ambitious elimination scenario, reached US$708 million. Stipulated WHO target for 2030 cannot be accomplished without scaling up treatment to 490 000 per year, and maintaining it for a decade.

Conclusion

HCV-TasP is a highly impactful and potent approach to control Pakistan’s HCV epidemic and achieve elimination by 2030.

Keywords: incidence, prevalence, mathematical model, treatment as prevention, Middle East and North Africa

Strengths and limitations of this Study.

We used a nationally representative survey and a comprehensive database of systematically gathered hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibody prevalence data to fit the scale and the trend of the HCV epidemic in Pakistan.

We assessed the implications of HCV treatment as prevention in Pakistan using different plausible treatment scenarios from a conservative baseline scale-up scenario up to an ambitious elimination scenario.

Future projections were generated by fitting the model to past and current data, but could be influenced by factors difficult to predict at present.

Introduction

Viral hepatitis is the seventh leading cause of death globally.1 Half of viral hepatitis deaths are attributed to hepatitis C virus (HCV).1–3 Pakistan is one of the most affected countries by this virus where HCV antibody (Ab) prevalence is estimated at 4.3% in 2017,4 with genotype 3 being most common in all provinces.5 Against this backdrop, HCV treatment has undergone a revolution since 2013. Introduction of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) furnished shorter and well-tolerated treatment regimens, with a success rate exceeding 90%.6 With the availability of DAAs, the WHO is calling for ambitious global targets for diagnosis, treatment and cure of viral hepatitis, signalling a major momentum towards HCV elimination by 2030.7

The Ministry of Health in Pakistan has launched its first National Hepatitis Strategic Framework following the WHO global targets.8 9 Importantly, the Government of Pakistan has made a commitment to provide diagnosis, treatment and care to patients infected by HCV free of cost in all provinces, through four regional Hepatitis Prevention and Control programmes.8 HCV patients will have access to DAA generics (eg, generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir) with a cost of <US$100 per treatment course per person—one of the lowest costs globally.8–10

Following the recent proof-of-concept and approach of HCV treatment as prevention (TasP) in Egypt11 and our developed epidemiological model for the HCV epidemic in Pakistan,4 we aimed to assess the implications of HCV-TasP in Pakistan. We did so through different scenarios for scaling up and sustaining the programme including an elimination scenario by 2030, where elimination is defined as an incidence rate of <1 per 100 000 person-year.11

Materials and methods

Mathematical model

Starting from our model for the Pakistan epidemic,4 we implemented an age-structured mathematical model as an adaptation and extension of earlier models and guidelines.4 11 12 Details of the model and parameterisation can be found in the supplementary material and in references.4 11

Briefly, the model is a population-level compartmental mathematical model that describes HCV transmission in the whole population. The model stratified the population into categories according to level of HCV risk of exposure, status and stage of infection and age group. The model divided Pakistan’s population into seven age groups based on the available HCV Ab prevalence data, and accounted for heterogeneity in risk of exposure to the infection by incorporating five risk groups in the modelled population. Individuals from different risk and age groups mixed in the model according to mixing matrices that include both an assortative component and a proportionate component.4 11 13 14 The force of infection was defined in terms of the effective contact rates, HCV transmission probability per contact by HCV stage and mixing among the different age and risk groups.

Detailed descriptions of assumptions and model structure can be found in S1 Text and online supplementary table S1.

bmjopen-2018-026600supp001.pdf (294.1KB, pdf)

Data sources and model fitting

The model was parameterised using empirical data for HCV natural history and transmission (online supplementary text S2 and table S2). Demographic data were derived from the database of the Population Division of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs,15 and Pakistan’s sixth Population and Housing Census-2017.16 Per our modelled epidemic in Pakistan,4 trends were estimated by fitting the model to a nationally representative and probability-based HCV Ab prevalence survey conducted in 2007–2008,17 and a comprehensive database of systematically gathered HCV Ab prevalence data.4 18 Detailed description of the model fitting to the data can be found in Ayoub et al.4

Epidemiological and programme indicators

To inform public health response and following our approach for Egypt,11 we used epidemiological and programme indicators to assess the implications of Pakistan’s treatment programme. The definition of these measures can be found in online supplementary table S3. The year 2010 was chosen as a reference year for several comparisons of outcome measures as suggested by WHO as a reference year,7 19 to have comparisons over complete two decades (2010, 2020 and 2030), and for consistency with the approach for Egypt.11 Treatment cost per person was assumed at US$100, mainly covering the cost of the generic DAAs.9 20 Furthermore, we applied an annual discount rate of 3% on future expenditures and on future savings (the latter being defined as infections averted).

Treatment programme scenarios

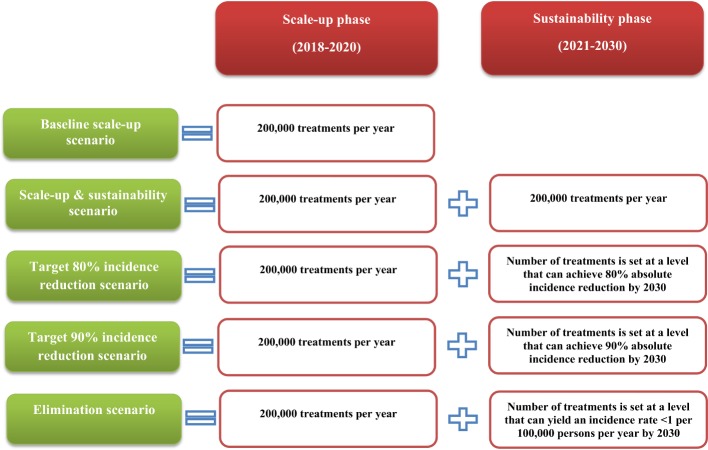

Informed by stakeholder discussions, programme data21 22 and experiences with similar scope programmes,11 23 24 the treatment programme was assumed to start in 2018 with a phase where the programme is being scaled up and that ends in 2020, followed by a phase where the programme is sustained from 2021 up to 2030, the elimination year. We assumed that there are no restrictions on treatment eligibility for any chronically infected person, regardless of liver disease stage or age. Success rate of treatment was assumed at 90%.25 We evaluated five HCV-TasP programme scenarios ranging from a conservative baseline scale-up scenario up to an ambitious elimination scenario (summarised in figure 1).

Figure 1.

Assessed scenarios of Pakistan’s HCV treatment programme. The key features of the five assessed treatment programme scenarios in both the scale-up and sustainability phases.

Uncertainty analyses

To examine the range of uncertainty in the projected epidemic trajectories and treatment programme outcomes, we performed multivariable uncertainty analyses by implementing 1000 runs of the model. We assumed a 25% uncertainty around the parameters’ point estimates and applied Latin Hypercube sampling from a multidimensional distribution for the model’s structural parameters. Mean and associated 95% uncertainty interval were reported for HCV-TasP effectiveness and HCV incidence rate reduction (see online supplementary table S3 for definitions) by 2030 for each of the scenarios.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public were not involved in this study.

Results

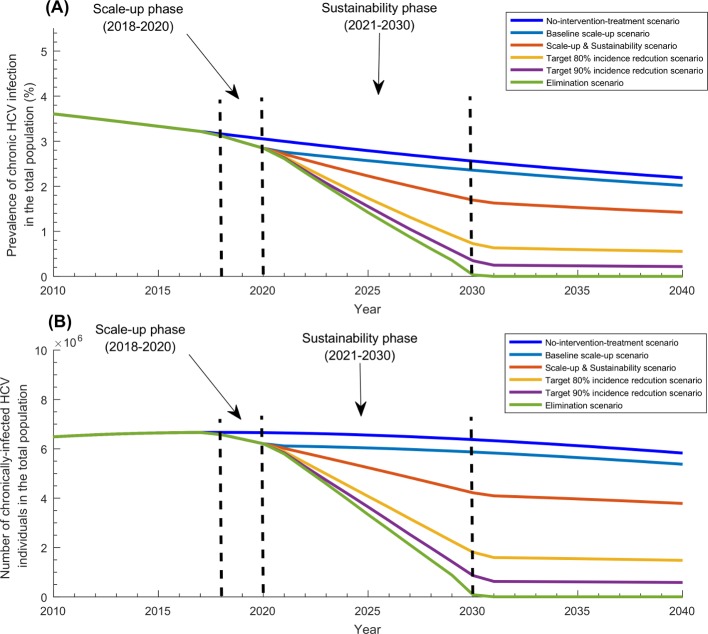

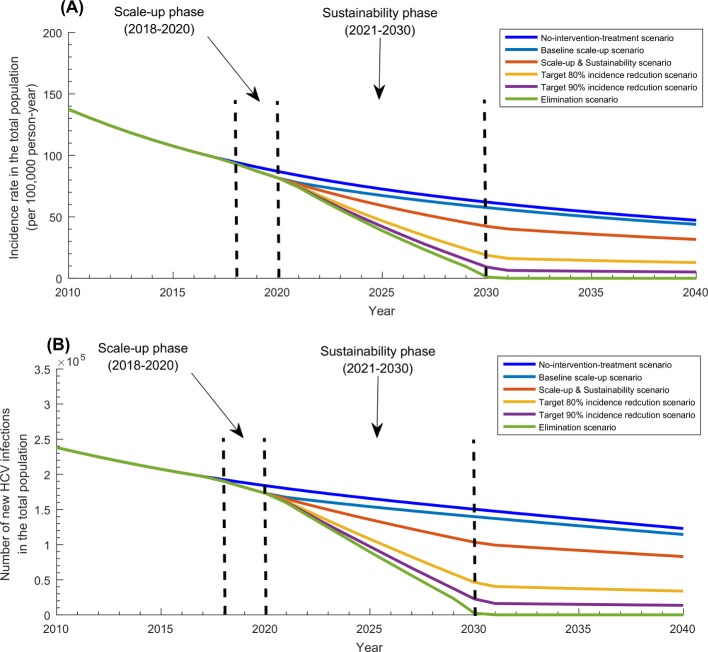

Table 1 and figures 2-4 display the projected impact of the five programme scenarios. In absence of the programme, the epidemic was forecasted to decline slowly. While the prevalence of chronic infection and number of chronically infected individuals (and in need of treatment) were estimated at 3.2% and 6 665 900 in 2018, they were projected to decline to 3.0% and 6 655 300 by 2020, and 2.6% and 6 372 100 by 2030, respectively (figure 2). Similarly, while HCV incidence rate per 100 000 person-year and number of new infections were estimated at 94 and 192 460 in 2018, they were projected to decline to 87 and 183 860 by 2020, and 62 and 150 360 by 2030, respectively (figure 3).

Table 1.

Projected outcomes for the five treatment programme scenarios by 2020 and by 2030

| Scenarios | Number of treatments per year (2018–2020) |

Number of treatments per year (2021–2030) |

Number of treatments from 2018 up to 2020 (millions) | Number of treatments from 2018 up to 2030 (millions) | Incidence reduction by 2020 compared with 2010 (%) | Incidence reduction by 2030 compared with 2010 (%) | Number of HCV infections averted by 2020 | Number of HCV infections averted by 2030 | Number of treatments per infection averted by 2020 | Number of treatments per infection averted by 2030 | Cost per infection averted by 2020 (US$) | Cost per infection averted by 2030 (US$) |

| Baseline scale-up scenario | 200 000 | — | 0.60 | 0.60 | 27% | 41% | 13 403 | 126 221 | 44.7 | 4.7 | 4336 | 456 |

| Scale-up and sustainability scenario | 200 000 | 200 000 | 0.60 | 2.60 | 27% | 57% | 13 403 | 301 259 | 44.7 | 8.6 | 4336 | 834 |

| Target 80% incidence reduction scenario | 200 000 | 490 000 | 0.60 | 5.50 | 27% | 80% | 13 403 | 568 869 | 44.7 | 9.7 | 4336 | 941 |

| Target 90% incidence reduction scenario | 200 000 | 599 000 | 0.60 | 6.60 | 27% | 90% | 13 403 | 675 640 | 44.7 | 9.8 | 4336 | 951 |

| Elimination scenario | 200 000 | 670 000 | 0.60 | 7.30 | 27% | 99% | 13 403 | 750 547 | 44.7 | 9.7 | 4336 | 941 |

HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Figure 2.

Impact of the five treatment programme scenarios on HCV chronic infection in Pakistan. (A) Prevalence of chronic HCV infection in the total population of Pakistan in the baseline scenario of no-treatment-intervention compared with the five treatment programme scenarios. (B) Number of individuals with HCV chronic infection in the total population of Pakistan in the baseline scenario of no-treatment-intervention compared with the five treatment programme scenarios. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Figure 3.

Impact of the five treatment programme scenarios on HCV incidence in Pakistan. (A) HCV incidence rate in the total population of Pakistan in the baseline scenario of no-treatment-intervention compared with the five treatment programme scenarios. (B) Annual number of new HCV infections in the total population of Pakistan in the baseline scenario of no-treatment-intervention compared with the five treatment programme scenarios. HCV, hepatitis C virus.

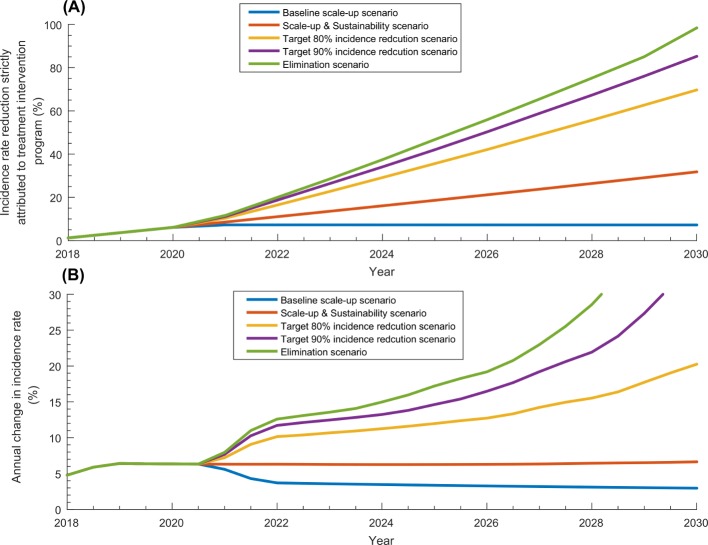

Figure 4.

Incidence rate reduction in the scale-up phase and sustainability phase. (A) Incidence rate reduction in the total population of Pakistan strictly attributed to each of the five treatment programme scenarios. (B) Annual change in incidence rate in each of the five treatment programme scenarios.

While total number of treatments administered by the end of the scale-up phase (in 2020) was 600 000 across the scenarios, by the end of the sustainability phase in 2030, it ranged between 0.6 million in the baseline scale-up scenario and 7.3 million in the elimination scenario. While incidence reduction was estimated at 27% by 2020 (with respect to 2010 incidence), it ranged between 41% and 99% by 2030. While prevalence of chronic infection declined to 2.8% by 2020, it ranged between 2.4% and 0.03% by 2030. While number of chronically infected individuals declined to 6 206 000 by 2020, it ranged between 5 868 600 and 8604 by 2030.

Annual reduction in incidence rate in the baseline scale-up scenario was around 6% per year up to 2020 and declined thereafter, but in the remaining scenarios, it ranged between 6% and 15% per year up to 2025 and then increased thereafter. While incidence rate reduction due to the programme was estimated at 6.1% by 2020, it ranged between 7.2% and 98.5% by 2030. While number of averted infections was estimated at 13 403 by 2020, it ranged between 126 221 and 750 547 by 2030.

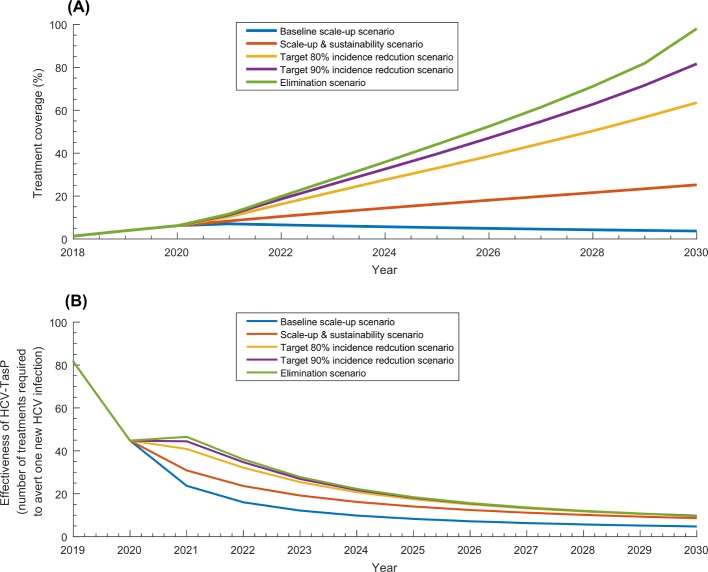

Table 1 and figure 5 show key programme indicators for all programme scenarios. Treatment coverage in 2020 reached 6.2% across the scenarios, and by 2030, it ranged between 3.7% in the baseline scale-up scenario and 98.7% in the elimination scenario (figure 5A). Programme cost ranged between US$58.2 million and US$708.1 million by 2030. HCV-TasP effectiveness was around 45 by 2020, 18 by 2025 and 10 by 2030 across the various scenarios (table 1 and figure 5B). Cost per infection averted declined from US$4336 by 2020 to around US$900 by 2030 across the scenarios (table 1).

Figure 5.

Key programme indicators for the five treatment programme scenarios. (A) Treatment coverage defined as proportion of all those living with chronic HCV infection that have been treated with direct-acting antivirals. (B) Effectiveness of HCV treatment as prevention (HCV-TasP) defined as number of treatments required to avert one new HCV infection. HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCV-TasP, hepatitis c virus treatment as prevention.

The multivariable uncertainty analyses supported the validity of our results and findings (online supplementary figure S1).

Discussion

Pakistan is one of the most affected countries by HCV with about 10% of the global number of chronic infections, and 10% of the global HCV incidence.4 22 26 This study investigated and quantified the utility of HCV-TasP in this country and demonstrated that HCV-TasP is a strategic and indispensable approach to control the epidemic and to reach the WHO elimination target by 2030.

In context of availability of heavily discounted DAA generics in Pakistan, at a cost of <US$100 for a treatment course,9 20 27 there is a historic opportunity to control the HCV epidemic at a relatively low cost of <US$1 billion distributed over a decade and a half. This cost is minimal considering the future healthcare costs that are being averted, and other costs in terms of productivity, disability and premature mortality. With the time lag between infection and disease sequelae,28 lack of a meaningful and immediate scale-up of HCV-TasP will be translated into a growing disease burden of liver cirrhosis and cancer that Pakistan cannot afford. The strikingly persistent incidence4 adds up to an immense opportunity cost with failure to control the epidemic.

In all scenarios, HCV-TasP achieved substantial if not huge impact on incidence and chronic infection prevalence. By 2030, prevalence of chronic infection can reach 2.4%–0.03%, incidence reduction ranged between 41%–99% and incidence rate reduction due to the programme ranged between 7%–98%. The impact of the programme was also prompt to materialise with an annual incidence rate reduction of around 6% in the initial years. In the most ambitious elimination scenario, a total of 7.3 million individuals would have been treated and around 750 000 infections would have been averted, by 2030. For every nine DAA treatments, one infection would be averted by 2030, at a cost of about US$900. These key programme indicators illustrate how HCV-TasP is a cost-effective and potent intervention, and very likely a cost saving one against disease sequelae costs.

Pakistan has launched its first National Hepatitis Strategic Framework where free diagnosis, treatment,and care are being provided to infected people in different provinces through four Hepatitis Prevention and Control programmes.8 Pakistan has one of the least expensive DAAs worldwide with the introduction of locally produced generics.9 27 Despite the affordability of DAAs,20 scale-up has been very modest with only 311 000 treated infections since DAA introduction in 2013.22 Our results indicate that the WHO global target of 80% incidence reduction by 2030 cannot be attained unless the number of treatments per year reaches 490 000, and is kept at this level for a decade.

A recent modelling work also assessed the impact of HCV-TasP in Pakistan.29 The authors’ conclusions agreed with our conclusions that HCV-TasP is an effective and compelling intervention against HCV transmission. However, some of the results differed. They projected an increase in incidence and chronic infection prevalence in absence of treatment, but our analyses projected a slow decline. This difference arose from differences in the model input data. They used data of the national (2007–2008) survey,17 surveys among people who inject drug (PWID) and blood donor testing. Meanwhile, we used data of the national (2007–2008) survey and an extensive database of HCV Ab prevalence data generated through a systematic review.4 18 Their analyses considered also different treatment programme scenarios than ours. With the differences in epidemic projections, they estimated substantially higher number of treatments to reach the WHO global target by 2030 than we did.

The relevance and feasibility of scaling up Pakistan’s programme can be seen in Egypt’s successful experience of scaling up the treatment programme.11 30 31 With the rapidly declining incidence and two million less prevalent chronic infections in Egypt,11 Pakistan’s programme can be even more impactful. By reaching elimination by 2030, the number of averted infections will be more than 50% higher than that in Egypt and more cost effective—10 treatments are needed to avert one infection in Pakistan compared with 12 in Egypt.

Despite the opportunity for scaling up HCV-TasP, the programme may soon encounter a major hurdle: identifying chronically infected individuals. The programme will not be able to yield its potential without active case finding. Our understanding of HCV epidemiology in Pakistan remains insufficient to develop cost-effective screening strategies,4 18 unlike Egypt where the epidemic is thoroughly investigated.11 32–40 While an understanding of epidemic drivers is being developed,18 41 screening can initially target >40 birth cohorts, who are more affected,4 17 and provinces with higher prevalence.17 With evidence for a major role for healthcare exposures18 42 and injecting drug use,18 43 44 targeting screening to these settings could be effective. Screening can also be scaled up using awareness campaigns and accessible mobile and fixed testing units, and should be targeting geographic localities with higher HCV prevalence.34

A recent study provided a conceptual map for a testing programme with focus on Pakistan and Egypt.45 The study showed that testing strategies can be much more efficient through population prioritisation by risk of exposure. For example, testing efficiency was highest by targeting, respectively, populations with liver conditions, PWID, populations with high-risk healthcare exposures and special clinical populations, where only 2–4 tests would be needed to identify a chronic infection, followed by populations at intermediate risk, and eventually general populations.

Current evidence suggests that HCV transmission in Pakistan is mostly driven by healthcare-related exposures, such as poor sterilisation of medical equipment, intravenous infusions and therapeutic injections.18 46–50 Although Pakistan has made strides to improve blood screening, safe injection and other infection control measures, and has been increasing HCV treatment coverage,10 51–54 commitment to prevention in the different segments of the healthcare system is warranted for this country to reduce further HCV incidence and to accomplish the HCV elimination target by 2030.

As for limitations of the present analyses, we did not include previous treatments (prior to 2018), but treatment coverage has been limited up to today.22 We assumed any chronically infected individual can be treated, but treatment may not be indicated for all. The cost per infection averted included only the cost of the drug and its direct implementation, but it did not include the cost of screening/testing to identify the chronically infected individuals. Future work needs to explore the cost effectiveness of combined HCV testing and treatment programmes. Most biological parameters used in the model were found in the literature based on studies including PWID, which may affect their generalisability. Future incidence can be uncertain as it depends on unpredictable factors, such as scale-up of other interventions. We used a complex mathematical model to describe HCV transmission in the population, but predictions may be contingent on type of model and its input data. To account (partially) for limitations, we performed multivariable uncertainty analyses, and these affirmed our results (online supplementary figure S1).

In conclusion, we assessed the impact of HCV-TasP in Pakistan through different programme scenarios. Projected programme outcomes demonstrated HCV-TasP as a strategic and indispensable approach to control the epidemic and to achieve elimination by 2030. Pakistan has a golden opportunity to avert 750 000 new infections, and to eliminate much of HCV chronic infections by expanding its treatment programme.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HHA designed the mathematical model, conducted the analyses and wrote the first draft of the paper. LJA-R conceived and led the design of the study and model, analyses and drafting of the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This publication was made possible by NPRP grant number 9-040-3-008 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The findings achieved herein are solely the responsibility of the authors. The authors are also grateful for support provided by the Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Biomathematics Research Core at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2016;388:1081–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30579-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Maheshwari A, Ray S, Thuluvath PJ. Acute hepatitis C. The Lancet 2008;372:321–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61116-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:558–67. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ayoub HH, Al Kanaani Z, Abu-Raddad LJ. Characterizing the temporal evolution of the hepatitis C virus epidemic in Pakistan. J Viral Hepat 2018;25:670–9. 10.1111/jvh.12864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mahmud S, Al-Kanaani Z, Chemaitelly H, et al. Hepatitis C virus genotypes in the Middle East and North Africa: Distribution, diversity, and patterns. J Med Virol 2018;90:131–41. 10.1002/jmv.24921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zoulim F, Liang TJ, Gerbes AL, et al. Hepatitis C virus treatment in the real world: optimising treatment and access to therapies. Gut 2015;64:1824–33. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, 2016-2021. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. Pakistan tackles high rates of hepatitis from many angles. 2017. http://www.who.int/features/2017/fighting-hepatitis-pakistan/en/ (Accessed 3 Jan 2018).

- 9. National Hepatitis Strategic Framework launched. 2017. http://nation.com.pk/09-Oct-2017/national-hepatitis-strategic-framework-launched (Accessed 3 Jan 2018).

- 10. Moin A, Fatima H, Qadir TF. Tackling hepatitis C—Pakistan’s road to success. The Lancet 2018;391:834–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30462-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ayoub HH, Abu-Raddad LJ. Impact of treatment on hepatitis C virus transmission and incidence in Egypt: A case for treatment as prevention. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:486–95. 10.1111/jvh.12671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delva W, Wilson DP, Abu-Raddad L, et al. HIV treatment as prevention: principles of good HIV epidemiology modelling for public health decision-making in all modes of prevention and evaluation. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001239 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garnett GP, Anderson RM. Factors controlling the spread of HIV in heterosexual communities in developing countries: patterns of mixing between different age and sexual activity classes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 1993;342:137–59. 10.1098/rstb.1993.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Awad SF, Abu-Raddad LJ. Could there have been substantial declines in sexual risk behavior across sub-Saharan Africa in the mid-1990s? Epidemics 2014;8:9–17. 10.1016/j.epidem.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects the 2015 Revision, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Population Census 2017. 2017. http://www.pbscensus.gov.pk/

- 17. Qureshi H, Bile KM, Jooma R, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral infections in Pakistan: findings of a national survey appealing for effective prevention and control measures. East Mediterr Health J 2010;16 Suppl:15–23. 10.26719/2010.16.Supp.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Al Kanaani Z, Mahmud S, Kouyoumjian SP, Abu-Raddad LJ, et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Pakistan: systematic review and meta-analyses. R Soc Open Sci 2018;5:180257 10.1098/rsos.180257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirnschall G. WHO 2016-2021 Global Health Sector Strategy Viral Hepatitis. The First Meeting of the National Focal Points for Viral Hepatitis. Cairo, Egypt, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Price of Hepatitis-C drug fixed at Rs 5,868. 2016. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/97674-Price-of-Hepatitis-C-drug-fixed-at-Rs5868 (Accessed 3 Jan 2018).

- 21. World Health Organization. Combating Hepatitis B and C to Reach Elimination by 2030. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Polaris Observatory. 2018. http://polarisobservatory.org/polaris/hepC.htm

- 23. Awad SF, Sgaier SK, Tambatamba BC, et al. Investigating Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Program Efficiency Gains through Subpopulation Prioritization: Insights from Application to Zambia. PLoS One 2015;10:e0145729 10.1371/journal.pone.0145729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Awad SF, Sgaier SK, Ncube G, et al. A Reevaluation of the Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision Scale-Up Plan in Zimbabwe. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140818 10.1371/journal.pone.0140818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Estes C, Abdel-Kareem M, Abdel-Razek W, et al. Economic burden of hepatitis C in Egypt: the future impact of highly effective therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:696–706. 10.1111/apt.13316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization. The Global Viral Hepatitis Report, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization. Key facts on hepatitis C treatment. http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/access/hepCtreat_key_facts/en/ (Accessed 3 Jan 2018).

- 28. Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Dore GJ. Epidemiology and natural history of HCV infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;10:553–62. 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim AG, Qureshi H, Mahmood H, et al. Curbing the hepatitis C virus epidemic in Pakistan: the impact of scaling up treatment and prevention for achieving elimination. Int J Epidemiol 2018;47:550–60. 10.1093/ije/dyx270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. El-Akel W, El-Sayed MH, El Kassas M, et al. National treatment programme of hepatitis C in Egypt: Hepatitis C virus model of care. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:262–7. 10.1111/jvh.12668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Elsharkawy A, El-Raziky M, El-Akel W, et al. Planning and prioritizing direct-acting antivirals treatment for HCV patients in countries with limited resources: Lessons from the Egyptian experience. J Hepatol 2018;68 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.11.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frank C, Mohamed MK, Strickland GT, et al. The role of parenteral antischistosomal therapy in the spread of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Lancet 2000;355:887–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06527-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Benova L, Awad SF, Miller FD, et al. Estimation of hepatitis C virus infections resulting from vertical transmission in Egypt. Hepatology 2015;61:834–42. 10.1002/hep.27596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cuadros DF, Branscum AJ, Miller FD, et al. Spatial epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt: analyses and implications. Hepatology 2014;60:1150–9. 10.1002/hep.27248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miller FD, Abu-Raddad LJ. Evidence of intense ongoing endemic transmission of hepatitis C virus in Egypt. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:14757–62. 10.1073/pnas.1008877107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller FD, Abu-Raddad LJ. Quantifying current hepatitis C virus incidence in Egypt. J Viral Hepat 2013;20:666–7. 10.1111/jvh.12090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mohamoud YA, Mumtaz GR, Riome S, et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in Egypt: a systematic review and data synthesis. BMC Infect Dis 2013;13:1 10.1186/1471-2334-13-288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kouyoumjian SP, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ. Characterizing hepatitis C virus epidemiology in Egypt: systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-regressions. Sci Rep 2018;8:1661 10.1038/s41598-017-17936-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in the World Health Organization Eastern Mediterranean Region: Implications for strategic action. In Press 2018.

- 40. Ministry of Health and Population [Egypt], El-Zanaty and Associates [Egypt], ICF International. Egypt Health Issues Survey 2015. Cairo, Egypt and Rockville, Maryland, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Trickey A, May MT, Davies C, et al. Importance and Contribution of Community, Social, and Healthcare Risk Factors for Hepatitis C Infection in Pakistan. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017;97:1920–8. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Alaei K, Sarwar M, Juan SC, et al. Healthcare and the Preventable Silent Killer: The Growing Epidemic of Hepatitis C in Pakistan. Hepat Mon 2016;16 10.5812/hepatmon.41262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mumtaz GR, Weiss HA, Abu-Raddad LJ. Hepatitis C virus and HIV infections among people who inject drugs in the Middle East and North Africa: a neglected public health burden? J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18:20582 10.7448/IAS.18.1.20582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mumtaz GR, Weiss HA, Thomas SL, et al. HIV among people who inject drugs in the Middle East and North Africa: systematic review and data synthesis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001663 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chemaitelly H, Mahmud S, Kouyoumjian SP, et al. Who to Test for Hepatitis C Virus in the Middle East and North Africa?: Pooled Analyses of 2,500 Prevalence Measures, Including 49 Million Tests. Hepatol Commun 2019;3:325–39. 10.1002/hep4.1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Aslam M, Aslam J, Mitchell BD, et al. Association between smallpox vaccination and hepatitis C antibody positive serology in Pakistani volunteers. J Clin Gastroenterol 2005;39:243–6. 10.1097/01.mcg.0000153286.02694.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Abbas Z, Jeswani NL, Kakepoto GN, et al. Prevalence and mode of spread of hepatitis B and C in rural Sindh, Pakistan. Trop Gastroenterol 2008;29:210–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Idrees M, Lal A, Naseem M, et al. High prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the largest province of Pakistan. J Dig Dis 2008;9:95–103. 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2008.00329.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hashmi A, Saleem K, Soomro JA. Prevalence and factors associated with hepatitis C virus seropositivity in female individuals in islamabad, pakistan. Int J Prev Med 2010;1:252–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ahmed F, Irving WL, Anwar M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in Kech District, Balochistan, Pakistan: most infections remain unexplained. A cross-sectional study. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:716–23. 10.1017/S0950268811001087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Government of Pakistan, Ministry of Environment. Hospital waste managment rules, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zaheer HA, Waheed U. Blood safety system reforms in Pakistan. Blood Transfus 2014;12:452 10.2450/2014.0253-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zafar A, Habib F, Hadwani R, et al. Impact of infection control activities on the rate of needle stick injuries at a tertiary care hospital of Pakistan over a period of six years: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis 2009;9:78 10.1186/1471-2334-9-78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ikram A, Hussain Shah SI, Naseem S, et al. Status of hospital infection control measures at seven major tertiary care hospitals of northern punjab. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2010;20:266–70. doi:04.2010/JCPSP.266270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026600supp001.pdf (294.1KB, pdf)