Abstract

Objectives

To investigate if self-reported high physical demand at work, objective physical workload using a job exposure matrix (JEM) and fear-avoidance beliefs are associated with reported sick leave in the previous year in persons with low back pain (LBP). Second, to investigate if the effects of fear-avoidance and self-reported high physical demand at work on sick leave are modified by the objective physical workloads.

Settings

Participants were recruited from general practice and by advertisement in a local newspaper.

Participants

305participants with a current period of 2–4 weeks LBP and self-reported difficulty in maintaining physically demanding jobs due to LBP were interviewed, clinically examined and had an MRI at baseline.

Main outcome measures

Independent variables were high fear-avoidance, self-reported high physical demand at work and objective measures of physical workloads (JEM). Outcome was self-reported sick leave due to LBP in the previous year. Logistic regression and tests for interaction were used to identify risk factors and modifiers for the association with self-reported sick leave.

Results

Self-reported physically demanding work and high fear-avoidance were significantly associated with prior sick leave due to LBP in the previous year with OR 1.75 95% CI (1.10 to 2.75) and 2.75 95% CI (1.61to 4.84), respectively. No objective physical workloads had significant associations. There was no modifying effect of objective physical workloads on the association between self-reported physical demand at work/high fear-avoidance and sick leave.

Conclusions

Occupational interventions to reduce sick leave due to LBP may have to focus more on those with high self-reported physical demands and high fear-avoidance, and less on individuals with the objectively highest physical workload.

Trial registration number

NCT02015572; Post-results.

Keywords: preventive medicine, rehabilitation medicine, rheumatology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

By using fear-avoidance score and self-reported workload together with a job exposure matrix (JEM) in the investigation of an association with sick leave, the validity problem with self-reported exposures has been reduced.

The study population consisted of workers with low back pain (LBP) and a physically demanding work, which is a clinically relevant sample of participants.

Workers with LBP but no self-reported physically demanding work were not included in the study with risk of lacking contrast among the included participants and thus risk of underestimation of associations.

Use of JEMs and dichotomising of the exposure data without a gold standard regarding cut-off values entails risk of misclassification of exposure.

Introduction

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is a common musculoskeletal disorder and is one of the leading causes of disability for the working population.1 2 In Denmark, back pain is estimated to accumulate 4.8 billion DKr in annual loss of productivity.3

The development of LBP is believed to be caused by a complex combination of both mechanical and physiological factors, and psychological, social and cultural factors.4 Systematic reviews have concluded that no single intervention is likely to be effective in preventing LBP, due to its multidimensional nature.5–7

Psychological factors such as high fear-avoidance beliefs (FAB) have proven to be an important prognostic factor for poor outcome in patients with non-specific LBP8 and, as such, have a predictive effect on sick leave.9 10 FAB are believed to influence the perception of pain resulting in catastrophising, fear and avoidance of physical activities. This leads to a vicious cycle of fear-avoidance behaviour, physical deterioration and social isolation—factors which may affect the ability to stay in a job.10

Self-reported workload exposures have been associated with LBP in the majority of studies11–13 despite the fact that self-reported workload exposures may entail a validity problem as individuals with musculoskeletal complaints tend to overestimate their exposures.14 A job exposure matrix (JEM) is a classification system linking occupation and industry titles with job-related exposures.15 This could be more accurate in estimating the real exposure of physical demands by reducing misclassification of exposure. However, we do not know if a JEM is better at predicting risk of sick leave. JEMs have been shown to be independent and valid measurements of physical demands in patients with primary hip and knee osteoarthritis,16 may be useful in the assessment of exposure for LBP patients and be associated with sick leave.

Objective

The objective of the study was (1) to investigate to what degree self-reported high physical demand at work, physical workload using the JEM and FAB are associated with reported sick leave in the previous year in a group of persons with LBP, and (2) if the association between fear-avoidance or self-reported high physical demand at work and reported sick leave is modified by the objective measures of physical workloads.

Methods

Design and ethics

The study was based on cross-sectional baseline data from a randomised controlled trial,17 and reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines.18

Participants and setting

Participants between 18 and 65 years of age with a current episode of 2–4 weeks of LBP and a self-reported physically demanding job were recruited from general practice, the outpatient clinic of the Department of Rheumatology, Frederiksberg Hospital, Denmark and by advertisement in a local newspaper. Potential participants were interviewed by telephone and screened for inclusion. Participants responded to ‘How physically demanding is your current job?’ Response categories were: ‘Very demanding, demanding, not very demanding, not at all demanding.’ Only those responding demanding or very demanding were included. Furthermore, the participants needed to express concern about the ability to maintain their current job (yes/no) and they had to have current employment for at least 30 hours/week. Individuals with pregnancy, severe somatic or psychiatric disease, cancer or metastatic disease, severe co-morbidity, treatment from or referral to outside providers (eg, surgery) or contraindications for having a conventional MRI were not included.

Variables

At the first visit (baseline) participants filled in a battery of questionnaires on a validated touch screen,19 underwent a physical examination and an MRI. The questionnaires investigated demographic information, co-morbidity, job category, previous history of LBP, physically demanding work, leisure time, physical activity, psychosocial work environment, general health status, history of work-related factors, work ability, back-specific disability, FAB, pain score and sick leave due to LBP. Diagnosis was based on symptoms, clinical examination and MRI.

Sick leave due to LBP was recorded by answering the following questions at baseline: ‘How many days of sick leave have you had due to LBP in the previous year?’ Categorised as short (1–7 days), medium (8–30 days), long (31–90 days), very long (over 90 days) or every day. Sick leave due to LBP was then dichotomised as low (1–7 days/year) and high (≥8 days/year) due to overall low sick leave among the participants.

FAB were assessed with the 16-item fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ).20 FABQ-W (Fear–Avoidance Belief Questionnaire Work subscale) is the sum of seven items (score range 0–42 points) with each item scored on a 7-point Likert scale from strongly disagree (0 points) to strongly agree (6 points). We defined high FAB as FABQ-W >20 points.21

Physically demanding work was evaluated both by self-report (having a very demanding or having a demanding current job) and with the use of the lower body JEM.16

Job titles from the baseline questionnaires were transformed into an occupational title in the Danish version of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (D-ISCO-88).22 The JEM consisted of 168 D-ISCO codes which were divided into 121 job groups. Occupational medicine experts assessed physical exposures during a working day and estimated time sitting, time standing/walking, time with whole body vibration, time kneeling and lifting (cumulated weight and number of heavy lifts >20 kg) in different jobs. The JEM did not include all job titles. Therefore, we matched missing job titles to a similar existing job title and exposure in the JEM. This was done by consensus preceded by independent matching by two occupational medicine experts. We dichotomised JEM variables according to median values to maximise strength of data and tested other exposure levels (standing/walking >6 hours/day, lifting a total of >1000 kg/day and lifting over 20 kg >15 times/day).

Statistical methods

Descriptive data are reported as point estimates (either frequency or mean and SD; the correlation between self-reported physical demand at work and FABQ-W >20 was calculated as Spearman’s rank correlation. We used a series of multivariate logistic regression models to investigate each measure from the lower body JEM separately. The models investigated the association between dichotomised sick leave due to LBP ≥8 days compared with 1–7 days during the previous year (outcome) and either self-reported physical demand at work, fear-avoidance or objective workload (JEM), all adjusted for age and sex. Analyses of the modifying effects of specific independent variables on effect of self-reported exposure were performed by adding an interaction term between the objective (JEM) and self-reported exposure (eg, FABQ-W and self-reported physically demanding work) to the regression model. Statistical analyses for descriptive data were done using SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute IC) and regression analyses were done using R V.3.2.2 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2016, https://www.R-project.org). All analyses used a significance level of 0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the general public were not involved in the design or development of the study.

Results

Participants

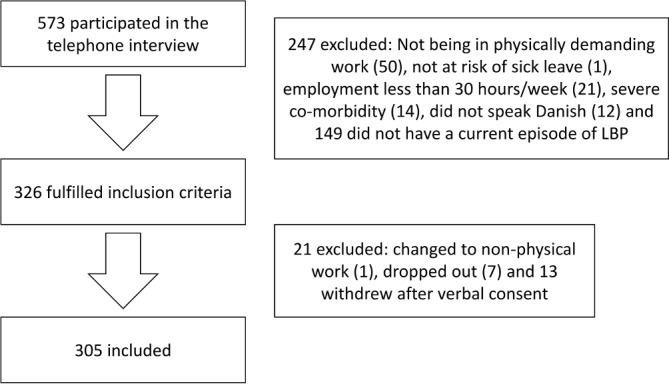

Based on the telephone interview 274 participants out of 573 interviewed were excluded, mainly due to not having a current episode of LBP or not having a physically demanding job. Of the 326 enrolled participants, 305 participants came to the first visit and were included in the study, see figure 1. A total of 55 job titles (48 among male and 24 among women) were represented and 41 participants were reassigned a new job title with similar exposure group due to lacking presence in the JEM (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the actual study in the GoBack trial.

Descriptive data

Participant characteristics are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants (n=305)

| Total | Self-reported physical demand | P value | ||

| Very demanding | Demanding | |||

| 305 (100%) | 144 (47.2%) | 161 (52.8%) | ||

| Age, years, mean±SD | 45.5±10.3 | 47.5±9.8 | 43.3±10.3 | <0.001* |

| Males, n (%) | 206 (67.5%) | 96 (66.7%) | 110 (68.3%) | 0.853† |

| Current smoking | 0.004† | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 112 (36.7%) | 63 (43.8%) | 49 (30.43%) | |

| No, n (%) | 193 (63.3%) | 81 (56.3%) | 112 (69.6%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9±4.2 | 27.2±4.1 | 26.7±4.4 | 0.278* |

| Actual sick leave due to LBP, n (%) | 34 (11.2%) | 23 (16.0%) | 11 (6.8%) | 0.020† |

| Sick leave due to LBP last year | 0.069† | |||

| 1–7 days, n (%) | 168 (55.1%) | 69 (47.9%) | 99 (61.5%) | |

| 8–30 days, n (%) | 104 (34.1%) | 104 (38.9%) | 56 (29.8%) | |

| 31–90 days, n (%) | 25 (8.2%) | 13 (9.0%) | 12 (7.5%) | |

| >90 days, n (%) | 8 (2.6%) | 2 (4.2%) | 6 (1.2%) | |

| Physical demanding workloads | ||||

| Standing/walking >5.44 hours/day, n (%) | 147 (48.2%) | 69 (47.9%) | 78 (48.5%) | 0.328† |

| Lifting >650 kg/day, n (%) | 148 (48.5%) | 77 (53.5%) | 71(44.1%) | 0.128† |

| Number of heavy lifts >7.7 times/day, n (%) | 145 (47.5%) | 75 (52.1%) | 70 (43.5%) | 0.165† |

| Clinical symptoms | 0.468† | |||

| LBP, n (%) | 170 (55.7%) | 85 (59.0%) | 85 (52.8%) | |

| LBP and+additional sciatica, n (%) | 86 (28.2%) | 36 (25.0%) | 50 (31.1%) | |

| LBP and+additional radiating pain, n (%) | 49 (16.1%) | 23 (16.0%) | 26 (16.2%) | |

| Primary diagnosis‡ | 0.498† | |||

| Spondylosis, n (%) | 155 (50.8%) | 68 (47.2%) | 87 (54.0%) | |

| Herniated disc, n (%) | 48 (15.7%) | 23 (16.0%) | 25 (15.5%) | |

| Spondylolisthesis, n (%) | 23 (7.5%) | 11 (7.6%) | 12 (7.5%) | |

| Spinal stenosis, n (%) | 12 (3.9%) | 4 (2.8%) | 8 (5.0%) | |

| Unspecific LBP, n (%) | 46 (15.1%) | 24 (16.7%) | 22 (13.7%) | |

| Spondyloarthritis, n (%) | 13 (4.3%) | 9 (6.3%) | 4 (2.5%) | |

| Other, n (%) | 8 (2.6%) | 5 (3.5%) | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Current job§ | 0.816† | |||

| Disco 1, 2: professionals and highly educated, n (%) | 21 (6.9%) | 9 (6.3%) | 12 (7.5%) | |

| Disco 3, 4, 5: office, teaching and nursing, n (%) | 99 (33.8%) | 47 (32.6%) | 56 (34.8%) | |

| Disco 6, 7, 8, 9: blue collar, n (%) | 181 (59.3%) | 88 (61.1%) | 93 (57.7%) | |

| Pain intensity (VAS 0–10) | ||||

| Average last 4 weeks, mean±SD | 5.6±1.9 | 5.3±1.9 | 5.99±1.9 | 0.002* |

| Actual, mean±SD | 4.5±2.1 | 4.3±2.1 | 4.7±2.0 | 0.105* |

| Highest intensity last 4 weeks, mean±SD | 7.1±2.0 | 6.75±2.0 | 7.5±2.0 | <0.001* |

| Fear-avoidance beliefs | <0.001† | |||

| Low (0–20), n (%) | 83 (27.2%) | 23 (16.0%) | 60 (37.3%) | |

| High (21-42), n (%) | 222 (72.8%) | 121 (84.0%) | 101 (62.7%) | |

| (0–42), mean±SD | 25.0±7.4 | 22.6±7.03 | 27.8±6.9 | <0.001* |

*t-test.

†X2 test.

‡Based on symptoms, clinical examination and MRI.

§Danish version of the International Standard Classification of Occupations.

BMI, body mass index; FABQ, fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire; LBP, low back pain; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Overall there was a low rate of sick leave due to LBP with 89.2% participants having less than 1 month of sick leave during the last 12 months.

Participants with a self-reported very physically demanding job had the lowest mean FAB, lowest current and average pain intensity and were more seldom smokers than participants reporting work as physically demanding.

Participants with a self-reported very physically demanding job were slightly, but significantly older compared with participants who only reported their job as demanding. There were no significant differences regarding sex, body mass index, JEM or educational level.

Factors associated with sick leave due to LBP

High self-reported physical demand and high FAB (FABQ-W >20) were both significantly associated with sick leave due to LBP ≥8 days/year with OR 1.75 (95% CI 1.10 to 2.75) and 2.75 (95% CI 1.61 to 4.84), respectively. After adjustment for age and sex, there was still a strong association, see table 2.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted OR for sick leave due to LBP according to self-rated physical demand, fear-avoidance beliefs and physical demanding workloads, respectively

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted* OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Self-rated physical demand | ||||

| Demanding | 1 | – | – | |

| Very demanding | 1.75 (1.10 to 2.75) | 0.018 | 1.60 (1.00 to 2.56) | 0.050 |

| Fear-avoidance beliefs | ||||

| FABQ-W≤20† | 1 | – | – | |

| FABQ-W>20† | 2.75 (1.61 to 4.84) | <0.001 | 2.67 (1.55 to 4.73) | 0.001 |

| Physical demanding workloads | ||||

| Standing/walking >5.44 hours/day | 0.85 (0.5 to 1.34) | 0.485 | 0.84 (0.53 to 1.33) | 0.462 |

| Lifting >650 kg/day | 1.41 (0.90 to 2.23) | 0.134 | 1.38 (0.87 to 2.18) | 0.174 |

| Number of heavy lifts >7.7 times/day | 1.60 (1.02 to 2.53) | 0.041 | 1.57 (0.99 to 2.50) | 0.056 |

*Adjusted for sex and age.

†Fear avoidance beliefs questionnaire in relation to work.

There was a positive association of lifting loads over 20 kg more than 7.7 times/day measured by JEM, which was borderline statistically significant after adjustment. None of the other physical workloads were significantly associated with sick leave due to LBP. There was very low exposure to kneeling and whole-body vibration and thus these exposures were not included in the analyses.

Interactions

Physically demanding workloads did not modify the association between self-reported physical demand and sick leave due to LBP (table 3).

Table 3.

Modifying effects of specific independent exposures on the association between self-reported physical demand and sick leave due to LBP

| Interaction OR* (95% CI) | P value | |

| Fear-avoidance beliefs | ||

| FABQ-W>20† | 1.27 (0.39 to 4.32) | 0.70 |

| Physically demanding workloads | ||

| Standing/walking >5.44 hours/day | 0.74 (0.29 to 1.86) | 0.52 |

| Standing/walking >6 hours/day | 1.21 (0.37 to 4.02) | 0.76 |

| Lifting >650 kg/day | 0.63 (0.24 to 1.59) | 0.32 |

| Lifting >1000 kg/day | 0.99 (0.37 to 2.64) | 0.97 |

| Number of heavy lifts >7.7 times/day | 0.75 (0.29 to 1.90) | 0.4 |

| Number of heavy lifts >15 times/day | 1.09 (0.28 to 4.39) | 0.90 |

*Adjusted for sex and age.

†Fear avoidance beliefs questionnaire in relation to work.

We repeated the analysis with other exposure levels (standing/walking >6 hours/day, lifting a total of >1000 kg/day and lifting over 20 kg >15 times/day) but this did not change the results.

Similar results of no modification effect of JEM variables were found between FABQ-W >20 and sick leave due to LBP (table 4).

Table 4.

Modifying effects of specific independent exposures on the association between fear-avoidance beliefs and sick leave due to LBP

| Interaction OR* (95% CI) | P value | |

| Physically demanding workloads | ||

| Standing/walking >5.44 hours/day | 0.77 (0.25 to 2.40) | 0.65 |

| Standing/walking >6 hours/day | 1.16 (0.30 to 5.29) | 0.83 |

| Lifting >650 kg/day | 0.88 (0.29 to 2.69) | 0.83 |

| Lifting >1000 kg/day | 1.11 (0.34 to 3.82) | 0.87 |

| Number of heavy lifts >7.7 times/day | 1.04 (0.34 to 3.16) | 0.95 |

| Number of heavy lifts >15 times/day | 1.38 (0.30 to 6.70) | 0.68 |

*Adjusted for sex and age.

There was a relatively poor correlation between self-reported physical demand and high FAB (FABQ-W >20) (r=0.29, p<0.0001). No correlation was found between self-reported physical demand and total kilograms lifted (r=−0.05, p=0.345), standing/walking time (r=0.07, p=0.254) or lifting loads over 20 kg (r=−0.05, p=0.349).

Discussion

Key results

In this study, self-reported high physical demand at work and high FAB were associated with reported sick leave due to LBP in the previous year. Standing/walking time and total number of kilograms lifted in 1 day had no association with reported sick leave due to LBP, whereas lifting over 20 kg several times a day may be associated. To some surprise, independent expert exposure assessments of workload did not modify the found association between self-reported high physical demand at work/high FAB and sick leave.

Our results confirmed the hypothesis that reported sick leave due to LBP in the previous year was associated with self-reported very physically demanding work and high FAB and to a lesser degree with ‘objective’ intensity of specific types of physical workloads. The poor correlation between JEM variables and self-reported physical demand supports this conclusion.

Limitations

The study is based on cross-sectional baseline data from a randomised controlled trial with the aim of retaining participants with physically demanding work and LBP in their job. This limits our ability to investigate causality. The trial included only participants with self-reported physically demanding or very demanding work and concern about their ability to maintain their current job. The resulting FAB score and self-reported physical demands may consequently have been inflated and can result in a lack of contrast among the participants and therefore between the groups. An association was found, and the estimate is probably conservative. Furthermore, use of JEMs entails risk of misclassification of exposure,23 as people with the same job title may have different exposures to physical workloads and using expert assessment of exposures at the occupational level may therefore miss potentially large individual differences and peak exposures. This can also lead to conservative estimates of associations. Another limitation is the dichotomising of the JEM-based physical workload exposures and of the FABQ-W. No gold standard exists regarding cut-off values for either. Several different methods have been proposed and used, and none have been validated.8 We used FABQ-W score at 20 or less for low FAB as proposed by others8 21 and medians for JEM-based physical workload exposures. This may also increase the risk of misclassification and therefore underestimate differences between groups. Self-reported sick leave is sensitive to recall bias. However, a meta-analysis has found reasonable rank order convergence with record-based data,24 for which reason we trust in the outcome data. This study includes a selected group of participants with physically demanding work. We did not adjust for socioeconomic status due to risk for over-adjusting since workers with lower socioeconomic status tend to have more physically demanding work.25 Sample size might explain the wide confidence intervals on all modifications by JEM, but since all ORs are close to 1, it is hardly a question of lack of strength in the data. Neither was there a problem with data contrast in exposure variables of the JEM.

Self-reported workload exposures are often used as exposure variable, although it may have a validity problem, as individuals with musculoskeletal complaints tend to overestimate their exposures.14 In this study, we have overcome this problem by using a JEM in combination with perceived self-reported physical demand.

Interpretation

The low correlation between self-reported physical demand and JEM variables and no modifying effect of JEM variables indicates that self-reported physical demand might be a more independent risk factor than expected. This may be an expression of the participants assessment of their own physical work capacity with LBP or another work-related factor that we have not investigated. Due to the exclusion of participants with low self-reported physical demand we were unable to explore this further.

The lower body JEM has recently been used on a large general working population and found an exposure-response relation between ton, lifting and kneeling years and all-cause long-term sick leave.26 The contrast with our results may be due to different definitions of exposure (medians vs ton/lifting years), older but healthier population and long-term versus relatively short-term sick leave.

Participants with different durations of LBP have different prognostic outcomes. It has been shown that FAB are associated with poor prognosis in LBP of any duration, but stronger with subacute LBP.8 27 Our results confirm the association between high FAB and sick leave although many of our participants, in addition to a subacute period of LBP, also had a longer history of LBP.

Self-reported physical workloads and sick leave have been found to be associated.11–13 Recently, 5076 workers in Denmark have been investigated and self-assessed lifelong hard physical work and in particular lifting/carrying tasks were found to be associated with all-cause long-term sick leave.28 Similar results was found in shipyard workers, where a borderline significant association between sick leave due to LBP and self-reported physical work factors was found.29 Our results are in line with these findings, although we used other exposure definitions. In contrast, a longitudinal study with 6 months follow-up among 407 industrial workers used high perceived physical workload as exposure variable, but found no association with sick leave due to LPB.30 This result can, however, be explained by low number of workers reporting sick leave or having LBP.

In a large review regarding acute LBP and sick leave, Steenstra et al found strong evidence for heavy work, in various definitions, as a predictor for duration of sick leave.31 A later review by the same author regarding patients with subacute and chronic LBP, a population more similar to ours, concluded insufficient to moderate evidence for an association with physical demands at work.25

Lifting, trunk flexion and rotation increased the risk of sick leave due to LBP in a longitudinal study with video-documented physical exposures.32 In our study, we did not use objective measurements but instead a JEM, which may explain the difference between the results because of the risk of misclassification of exposure by using a JEM. This illustrates the importance of further large studies with objective measures of physical workload and prospective designs.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that self-reported high physical demand at work and high fear-avoidance are associated with reported sick leave due to LBP in the previous year in individuals with physically demanding jobs. We found no association between reported sick leave due to LBP in the previous year and high physical workloads, except for number of heavy lifts measured by JEM. Interestingly, the high physical workloads did not modify the associations with sick leave in participants who rate their work as very demanding or with high fear-avoidance scores. The poor correlation between JEM variables and self-reported physical demand indicates that occupational interventions to reduce sick leave due to LBP may have to focus more on those with high self-reported physical demands and high fear-avoidance, and less on individuals with the objectively highest physical workload.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JP, LK, BBH, LMB, EMF and AIK: Study concept and design. JP, BBH, LMB and AIK: Data acquisition. JP, BBH and EMF: Statistical analysis. JP, LK, BBH, LMB, EMF, MB, PH, HB and AIK: Analysis and interpretation of data and critical revision and approval of the final manuscript. JP: Drafting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed drafts and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Danish Working Environment Research Fund (grant number 09-2012-09).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the local ethics committee (H-3-2013-161) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (approval number 2014-41-2673).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Research records and data collection are obtained according to the Danish Personal Data Act (DPA) guidelines and any extra data is available upon request under the terms of DPA and EU General Data Protection Regulation. The authors affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. Full data set to replicate the main analysis is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, et al. . The Epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:769–81. 10.1016/j.berh.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, et al. . Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015;386:2145–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flachs EM, Eriksen L, Koch MB. Sygdomsbyrden i Danmark – sygdomme. Copenhagen, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balagué F, Mannion AF, Pellisé F, et al. . Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2012;379:482–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60610-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Demoulin C, Marty M, Genevay S, et al. . Effectiveness of preventive back educational interventions for low back pain: a critical review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Eur Spine J 2012;21:2520–30. 10.1007/s00586-012-2445-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maher CG. A systematic review of workplace interventions to prevent low back pain. J Osteopath Med 2001;4:32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hilfiker R, Bachmann LM, Heitz CA, et al. . Value of predictive instruments to determine persisting restriction of function in patients with subacute non-specific low back pain. Systematic review. Eur Spine J 2007;16:1755–75. 10.1007/s00586-007-0433-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Weiser S, et al. . The role of fear avoidance beliefs as a prognostic factor for outcome in patients with nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:816–36. 10.1016/j.spinee.2013.09.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jensen JN, Karpatschof B, Labriola M, et al. . Do fear-avoidance beliefs play a role on the association between low back pain and sickness absence? A prospective cohort study among female health care workers. J Occup Environ Med 2010;52:85–90. 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c95b9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fritz JM, George SZ, Delitto A. The role of fear-avoidance beliefs in acute low back pain: relationships with current and future disability and work status. Pain 2001;94:7–15. 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00333-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andersen LL, Fallentin N, Thorsen SV, et al. . Physical workload and risk of long-term sickness absence in the general working population and among blue-collar workers: prospective cohort study with register follow-up. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:246–53. 10.1136/oemed-2015-103314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lund T, Labriola M, Christensen KB, et al. . Physical work environment risk factors for long term sickness absence: prospective findings among a cohort of 5357 employees in Denmark. BMJ 2006;332:449–52. 10.1136/bmj.38731.622975.3A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sundstrup E, Andersen LL. Hard Physical Work Intensifies the Occupational Consequence of Physician-Diagnosed Back Disorder: Prospective Cohort Study with Register Follow-Up among 10,000 Workers. Int J Rheumatol 2017;2017:1–8. 10.1155/2017/1037051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balogh I, Ørbaek P, Ohlsson K, et al. . Self-assessed and directly measured occupational physical activities--influence of musculoskeletal complaints, age and gender. Appl Ergon 2004;35:49–56. 10.1016/j.apergo.2003.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hawkes AP, Wilkins JR. Assessing agreement between two job-exposure matrices. Scand J Work Environ Health 1997;23:140–8. 10.5271/sjweh.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rubak TS, Svendsen SW, Andersen JH, et al. . An expert-based job exposure matrix for large scale epidemiologic studies of primary hip and knee osteoarthritis: the Lower Body JEM. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014;15:204 10.1186/1471-2474-15-204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hansen BB, Kirkeskov L, Christensen R, et al. . Retention in physically demanding jobs of individuals with low back pain: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:166 10.1186/s13063-015-0684-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Von EE, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. . guidelines for reporting observational studies Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Br Med J 2007;335:19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gudbergsen H, Bartels EM, Krusager P, et al. . Test-retest of computerized health status questionnaires frequently used in the monitoring of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized crossover trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:190 10.1186/1471-2474-12-190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, et al. . A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993;52:157–68. 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. George SZ, Fritz JM, Childs JD. Investigation of elevated fear-avoidance beliefs for patients with low back pain: a secondary analysis involving patients enrolled in physical therapy clinical trials. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008;38:50–8. 10.2519/jospt.2008.2647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Statistics Denmark. Danish ISCO-88 classification. 1996. http://www.dst.dk/da/statistik/dokumentation/Nomenklaturer/DISCO-88.aspx

- 23. Kauppinen T, Uuksulainen S, Saalo A, et al. . Use of the Finnish Information System on Occupational Exposure (FINJEM) in epidemiologic, surveillance, and other applications. Ann Occup Hyg 2014;58:380–96. 10.1093/annhyg/met074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johns G, Miraglia M. The reliability, validity, and accuracy of self-reported absenteeism from work: a meta-analysis. J Occup Health Psychol 2015;20:1–14. 10.1037/a0037754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Steenstra IA, Munhall C, Irvin E, et al. . Systematic review of prognostic factors for return to work in workers with sub acute and chronic low back pain. J Occup Rehabil 2017;27:369-381 10.1007/s10926-016-9666-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sundstrup E, Hansen ÅM, Mortensen EL, et al. . Cumulative occupational mechanical exposures during working life and risk of sickness absence and disability pension: prospective cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2017;43:415–25. 10.5271/sjweh.3663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wertli MM, Rasmussen-Barr E, Held U, et al. . Fear-avoidance beliefs-a moderator of treatment efficacy in patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Spine J 2014;14:2658–78. 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sundstrup E, Hansen ÅM, Mortensen EL, et al. . Retrospectively assessed physical work environment during working life and risk of sickness absence and labour market exit among older workers. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:114–23. 10.1136/oemed-2016-104279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alexopoulos EC, Konstantinou EC, Bakoyannis G, et al. . Risk factors for sickness absence due to low back pain and prognostic factors for return to work in a cohort of shipyard workers. Eur Spine J 2008;17:1185–92. 10.1007/s00586-008-0711-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. IJzelenberg W, Burdorf A. Risk factors for musculoskeletal symptoms and ensuing health care use and sick leave. Spine 2005;30:1550–6. 10.1097/01.brs.0000167533.83154.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Steenstra IA, Verbeek JH, Heymans MW, et al. . Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave in patients sick listed with acute low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med 2005;62:851–60. 10.1136/oem.2004.015842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hoogendoorn WE, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, et al. . High physical work load and low job satisfaction increase the risk of sickness absence due to low back pain: results of a prospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:323–8. 10.1136/oem.59.5.323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.