Abstract

Rationale

Ovulation confirmation is a fundamental component of the evaluation of infertility.

Purpose

To inform the design of a larger clinical trial to determine the effectiveness of a new home-based pregnanediol glucuronide (PDG) urine test to confirm ovulation when compared with the standard of serum progesterone.

Methods

In this observational prospective cohort study (single group assignment) in an urban setting (stage 1), a convenience sample of 25 women (aged 18–42 years) collected daily first morning urine for luteinisinghormone (LH), PDG and kept a daily record of their cervical mucus for one menstrual cycle. Serum progesterone levels were measured to confirm ovulation. Sensitivity and specificity were used as the main outcome measures. Estimation of number of ultrasound (US)-monitored cycles needed for a future study was done using an exact binomial CI approach.

Results

Recruitment over 3 months was achieved (n=28) primarily via natural fertility regulation social groups. With an attrition rate of 22%, specificity of the test was 100% for confirming ovulation. Sensitivity varied depending on whether a peak-fertility mucus day or a positive LH test was observed during the cycle (85%–88%). Fifty per cent of participants found the test results easy to determine. A total of 73 US-monitored cycles would be needed to offer a narrow CI between 95% and 100%.

Conclusion

This is first study to clinically evaluate this test when used as adjunct to the fertility awareness methods. While this pilot study was not powered to validate or test efficacy, it helped to provide information on power, recruitment and retention, acceptability of the procedures and ease of its use by the participants. Given this test had a preliminary result of 100% specificity, further research with a larger clinical trial (stage 2) is recommended to both improve this technology and incorporate additional approaches to confirm ovulation.

Trial registration number

Keywords: reproductive medicine, subfertility, gynaecology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study provides the first clinical evaluation of a novel urinary home test to confirm ovulation when used as adjunct to fertility awareness methods. It provided preliminary results that may indicate a test’s specificity of 100 % to confirm ovulation.

It obtained essential information for the design and execution of a future larger trial.

The size of the study is small as expected from a pilot study.

The study provided a power calculation for a future larger study incorporating ultrasound for its validation (n=73 cycles).

Test would certainly benefit from improving its visual readability and interpretation given its lower sensitivity (85%–88%).

Introduction

It is estimated that about 12%–15% of couples may experience infertility.1 2 The literature recommends providing couples with fertility education that encourages the use of fertility awareness methods (FAMs), promoting preconception health (ie, weight loss, smoking cessation), and prescribing low-cost fertility technologies (eg, point-of-care (POC) over-the-counter ovulation predictor kits) to increase the chances of spontaneous pregnancy.3–5

Ovulatory function assessment is a fundamental component of the standard evaluation of infertility.6 7 Among evidence-based approaches that can be done at home to assess ovulation, the urinary luteinising hormone (LH) tests (‘ovulation predictor kits’) that identify the mid-cycle surge of LH that precedes ovulation by 1–2 days are the most common.8 9 An alternate method to optimise fertility naturally and assess ovarian function is the monitoring of changes to the cervical mucus across the fertile interval.10 11 Both methods are predictive tools of impending ovulation. Confirmation that ovulation has already occurred can only currently be determined by performing a serum progesterone test in a laboratory12 (with an approximate cost of $C50 per test) or by using serial transvaginal ultrasound (US)7 (with an approximate cost of $C300 per procedure). In addition, both investigations require visits to a physician, specialised laboratory testing and in the case of US, it is often prohibitive due to its high costs and logistical demands.

Given this situation, our research group performed a secondary analysis based on urinary hormonal assays to investigate an alternative method for confirming ovulation. Results were presented in a 2013 study where we proposed that a helpful test for couples to confirm ovulation would be a competitive lateral flow assay home-based urinary strip test that measures pregnanediol-3a-glucuronide (PDG), the urinary metabolite of progesterone.13 The rational for the urinary strip idea was based on the fact that progesterone rises sharply only after ovulation, making its metabolite easily detectable in urine.14 15 PDG assays, similar to commercial urinary pregnancy or ovulation predictor kits, could therefore be potentially used as markers to confirm ovulation. However, a major limitation in the analysis of random urinary biochemical markers is the fluctuation in volume between samples.16 Creatinine adjustment is the most commonly used laboratory approach to overcome this problem but presents a significant technical obstacle for the development of any home-based POC test.

In order to circumvent this significant technical challenge, our research team developed a novel concept that a urinary PDG kit with a threshold of ≥5 µg/mL might confirm ovulation as an adjunct to using FAMs. This conceptual model resulted in a theoretical 99%–100% specificity for ovulation confirmation if three consecutive days of positive PDG tested occurred either after the first day of a positive urinary LH test (threshold ≥20 mIU/mL) or the end of peak-fertility type cervical mucus.13 In 2016, an American company was first to develop and market a PDG test based on our research group’s theoretical analysis (figure 1). This current pilot study is the first stage for clinically assessing and validating the use of this POC urinary PDG identification kit to confirm that ovulation has occurred (Ovulation Double Check, MFB Fertility, Boulder, Colorado, USA, approximate cost of $C5.75 per unit). It also provides the feasibility and operational knowledge that would be needed to launch a future larger clinical trial (stage 2).

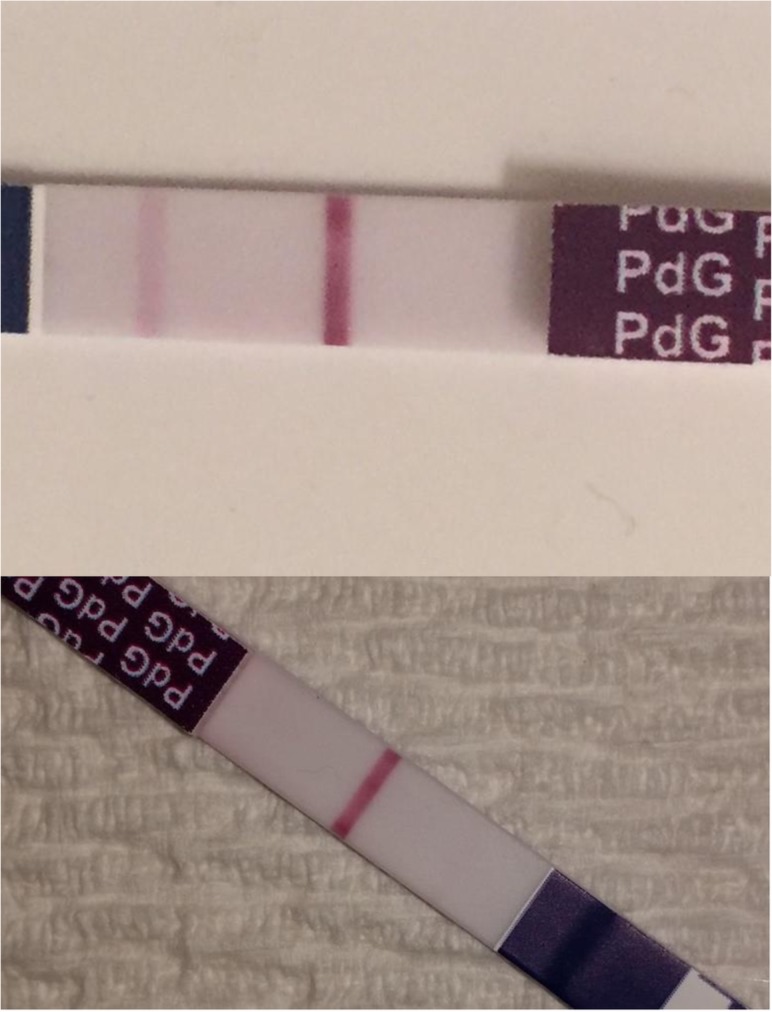

Figure 1.

PDG test visual results. Negative result (two lines) and positive result (one line).

Methods

Study participants

Patients were recruited from August to November 2017 based on a non-probability sample of the general female population in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Based on the usual number for a traditional feasibility study,17 we recruited a convenience sample of 25 English-speaking and French-speaking women of reproductive age (aged 18–42 years). Participants were approached via social media Facebook and recruitment flyers that were sent directly to local natural family planning/FAMs teachers and organisations. Recruitment was also extended to local family medical clinics associated with the University of Ottawa and local universities. Interested individuals were able to link to the Principal Investigator’s website to obtain information about the study.

Women were eligible for the study (inclusion criteria) if they were between the age of 18 and 42 years, had a menstrual cycle length of 25–35 days for the past 3 months, were able to provide informed consent and were willing to complete a participant trial diary and required blood draw. Women who were currently or had used (in the past 6 months) any hormonal contraception, were currently or recently (in the past 6 months) breast feeding, had used emergency contraception in the past two menstrual cycles or had a medical contraindication to frequent blood sampling, for example, anaemia or blood clotting disorder, were excluded (exclusion criteria). Achieving pregnancy during the study cycle, while not encouraged, was not an exclusion criterion.

Study design

This was a feasibility (pilot) observational prospective cohort study. Each woman was provided with a participant diary and asked to record their daily cervical mucus score, and their first morning urinary LH and PDG testing over the course of one menstrual cycle, starting on the first day of the menses and ending up to a maximum of 39 days or the start of next menses, whichever was first. The researcher had previously defined a four-point score based on the modified Colombo score18 for types of cervical mucus: (1) dry sensation, rough and itchy or nothing felt with nothing seen; (2) damp sensation with nothing seen; (3) damp sensation, with the appearance of thick, creamy, whitish, yellowish or sticky mucus; (4) wet, slippery, smooth sensation with the appearance of transparent, stretchy mucus (similar to a raw egg white). Score 4 type mucus was defined as peak-fertility type mucus. This mucus is related to oestrogen and identifies the ovulation window with 88% sensitivity.11

For this pilot study (stage 1), we confirmed ovulation based on our previously used model that used both serum progesterone and US as gold standards12 13 and showed that serum progesterone level is a well-accepted alternative to confirm whether an ovulation may have occurred. The postovulatory phase was confirmed with a serum progesterone level ≥5 ng/mL after presumptive ovulation as defined by FAMs (ie, after the first positive LH test or after peak-day type mucus, or if both absent, after day 17th of the cycle). The progesterone analysis was carried out using the Abbott Architect i2000SR analysis platform (Abbott Diagnostics, Illinois, USA) at LifeLabs medical laboratories. All assays were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions. To clarify, performance of US to asses for ovulation was purposefully not carried out at this stage in part due to the fact that there was lack of previous published data to accurately calculate power to estimate a proper number of cycles needed for this test.

Urinary LH tests (WONDFO One Step Ovulation Urine Test, License No.: 86004 Health Canada, threshold 25 mIU/mL) and PDG tests (threshold 5 ng/mL) were recorded as one or two lines in the participant diary. It was important to clarify with the participants that LH tests, direct solid-phase immunoassay type, provide a positive result as two lines (control and test), while the PDG tests, competitive solid-phase immunoassays, show positive result as one line (the test line disappears leaving the control line only visible) (figure 1).

Participants were required to meet with the research team at the study site at the beginning of the study to complete informed consent and receive study instructions. Instructions and photo examples were provided in paper form in English or French depending on the needs of the participants. Research staff followed-up with participants by phone and email at regular intervals throughout their cycle to assess diary completion, provide assistance and support with LH and PDG strips, and to inform participants of serum progesterone lab results and the need for additional blood draws. A close out visit was conducted at the study site at which time diaries were collected and participants were asked to complete a self-administered questionnaire to assess their experience with the kits and study procedures (online supplement 1).

bmjopen-2018-028496supp001.pdf (88.6KB, pdf)

Study analysis

The primary outcome measure was defined as the correlation of urine PDG test results to serum progesterone based in our previous theoretical work13: PDG positivity was defined as three consecutive first early morning daily urinary PDG positive tests (threshold ≥5 µg/mL) after either the first positive urine LH test or after the last day of score 4 type mucus (‘peak day’). Early luteal activity was confirmed with the use of serum progesterone after either LH positivity or the peak mucus sign. Secondary outcome measures were: (a) urine LH tests results and (b) cervical mucus as determined by the participant’s score. A positive LH test was defined as a threshold ≥25 mIU/mL. The chosen threshold of a single urinary LH test has been proven to be the best to predict ovulation in our previous published analysis.9 Peak mucus is defined as cervical mucus score of 4.18 A secondary analysis using the same statistical model for confirmation of ovulation was also performed using a single positive day occurring any time after the third day of either a LH positive or a peak day instead of necessitating three consecutive days of positive PDG.

Calculation of the sensitivity and specificity of this PDG test was conducted similarly to the one used in our previous theoretical study13: (I) a cycle with a positive PDG test in the preovulatory phase was classified as a false positive, that is, PDG positivity despite ovulation not having occurred. A cycle with no positive PDG tests in the preovulatory phase was classified as a true negative, that is, no PDG positivity before ovulation; (II) a cycle with a positive PDG test in the postovulatory phase was classified as a true positive, that is, PDG positivity after ovulation. A cycle with no positive PDG test in postovulatory phase was classified as a false negative, that is, no PDG positivity even though ovulation has occurred; (III) the sensitivity was estimated as the proportion of true positives cycles, that is, cycles with appropriate recognition of the postovulatory phase. The specificity was estimated as the proportion of true negatives cycles, that is, cycles with appropriate recognition of the preovulatory phase.

Each menstrual cycle was defined as consisting of a preovulatory phase and a postovulatory phase. The preovulatory phase was defined as the period comprising from the first day of menses to the estimated day of ovulation (EDO). The postovulatory phase is defined as starting the day after EDO. The EDO was defined as the day of the cycle between the first positive LH test or the peak-type mucus day and the positive serum progesterone. Estimation of number of US-monitored cycles needed for a future study was done using an exact binomial CI approach on the estimation of the specificity. We measured the specificity, rather than the sensitivity, given our goal was to avoid falsely confirming ovulation (ie, false negatives).13 All statistical analyses were performed using the R software (V.3.3.3, 2017 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Patient and public involvement

The study had a great deal of community interest. Enrolment was completed well in advance of the project plan. Calls to the recruitment centre continued well after the study was closed with many women interested in future studies. Although participant advisors were not used to assist in the planning of the pilot study, feedback on the use of the test kits and study procedures provided valuable information for planning future studies.

Results

Participants and cycle characteristics

Twenty-eight women were recruited sequentially in a span of 3 months with a cumulative enrolment rate greater than expected target recruitment per month. Out of those, 22 participants contributed 22 cycles for analysis (3 withdrew before recording or collection of any data for personal reasons, 1 participant did not submit her data and was lost to follow-up despite multiple attempts to contact her and 2 failed to follow the instructions for data collection and we are unable to retrieve any information). Age distribution in years was as follows: 20–24 (n=2), 25–29 (n=6), 30–34 (n=3), 35–39 (n=10) and 40–42 (n=1).

Cycle characteristics are presented in table 1. All 22 cycles were ovulatory-based serum progesterone. The luteal phase had a median length of 12 days. Of all 22 cycles, 2 (9%) did not have a positive LH test, 6 out of 22 (27%) of all cycles did not have a peak-fertility mucus day and 1 out of all 22 cycles had neither for both (5%). When three consecutive days of positive PDG testing were obtained following the first day of a positive LH test, it confirmed ovulation in 17 of 20 cycles (85%). Similarly, there was confirmation of ovulation in 14 of 16 cycles (87%) with three consecutive positive PDG tests after the last day of peak-fertility type mucus. When at least one positive PDG testing was obtained, the average number of luteal phase days identified were 8.82 (SEM: 0.82) and 8.79 (SEM: 0.87) days for LH positive and peak-fertility type mucus rules, respectively.

Table 1.

Menstrual cycles characteristics according to the luteinising hormone (LH), peak-fertility mucus and pregnanediol 3-glucuronide (PDG) daily tracking for both 3-day and 1-day PDG positivity (PDG+) rules

| Characteristics (22 cycles) | 3-daily consecutive PDG+ (3PDG+) after first positive urine LH test (LH+) or after ‘peak mucus day’ | 1 day PDG+ (1PDG+) after third day post first LH+ or after the third day post ‘peak mucus day’ | ||||

| Median (day) | Number of cycles | Range (days) | Median (day) | Number of cycles | Range (days) | |

| Cycle length (days) | 27 | 22 | 23–34 | 27 | 22 | 23–34 |

| Estimated day of ovulation | 15 | 22 | 11–21 | 15 | 22 | 11–21 |

| First day of LH positive (LH+) | 13 | 20 | 7–19 | 13 | 20 | 7–19 |

| Last day of peak-fertility mucus (‘peak day’) | 15 | 17 | 10–21 | 15 | 17 | 10–21 |

| First day of PDG positive (PDG+) | 18 | 21 | 13–27 | 18 | 21 | 13–27 |

| First infertile day after LH+ followed by PDG+ | 20 | 17 | 16–29 | 19 | 19 | 14–27 |

| First infertile day after ‘peak day’ followed PDG+ | 20 | 15 | 15–29 | 19 | 15 | 14–27 |

| Number of recognised infertile days after LH+PDG+ | 8 | 17 | 5–18 | 10 | 19 | 7–18 |

| Number of recognised infertile days after peak day+PDG+ | 8 | 15 | 5–17 | 9 | 15 | 7–16 |

Test performance

The PDG test’s specificities and sensitivities are shown in table 2. In our study, the specificity of the test was 100% for confirming ovulation. However, sensitivity of the test varied depending whether a peak-fertility mucus day or a positive LH test was observed during the cycle. Sensitivity was 85% if a positive LH test was followed by three consecutive positive PDG tests. Likewise, sensitivity was 88% for those cycles with a peak mucus day if it was followed by three consecutive positive PDG tests. Expressed differently, 15% and 12% of cycles were false negatives if using the LH+ and peak mucus day rules, respectively. For a single PDG test use, specificity remained at 100% with sensitivity increasing to 95% for the LH+ arm and remaining at 87% for the mucus arm. While having the same specificities, the use a single test seems to provide more infertile days as well as better sensitivities.

Table 2.

Performance of the urinary pregnanediol 3-glucuronide (PDG) test with respect to its sensitivity and specificity

| Rules for ovulation confirmation Total # menstrual cycles (n=22) |

Menstrual cycle scenarios | |||

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Scenario 4 | |

| First condition | First day luteinising hormone (LH)+ | Fertile peak mucus day | Third day after first LH+ | Third day after peak fertile mucus day |

| # of cycles that met the first condition | 20 | 17 | 20 | 17 |

| Second condition (follows first condition) | Three consecutive daily PDG+ | Three consecutive daily PDG+ | 1 day PDG+ | 1 day PDG+ |

| # of cycles that met the second condition | 17 | 15 | 19 | 15 |

| False positive (# of cycles) |

0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sensitivity (contingent on both conditions being met) (95% CI) | 85% (62 to 97) | 88% (64 to 99) | 95% (75 to 100) | 88% (64 to 99) |

| Specificity (contingent on both conditions being met) (95% CI) | 100% (81 to 100) | 100% (78 to 100) | 100% (82 to 100) | 100% (78 to 100) |

As for the estimation of the optimal number of US-monitored cycles needed to determine the specificity of using three consecutive tests versus one test to confirm ovulation, we calculated it to be 73 scans (95% CI 80% to 100%). The range 80%–100% was chosen based on the CI obtained for specificities for both the three-PDG and one-PDG options (table 2).

Poststudy feedback

Twenty-two participants completed the end-of-the-study questionnaire (online supplement 1). Out of 5 categories (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree and strongly disagree), 11 participants (50%) agreed with the statement that ‘the PDG urinary strip results were easy to determine’. Of the remaining, one ‘strongly agreed’ (4%) and five each answered as ‘neutral’ and ‘disagree’, respectively (23% each). In the comments sections, 11 participants voiced the theme that the test often had a remaining very faint line making it unclear whether the test was negative or positive. Alternatively, 14 participants (63%) either strongly agreed (n=8) or agreed (n=7) that they would purchase this product if they needed a home monitoring kit to determine whether they had ovulated or not. Four were neutral and three disagreed. The test interpretation did not seem to present a barrier despite having a different visual reading with other commonly used tests such as ovulation predictor kits (OPKs) or pregnancy tests. Participants appreciated visual aids to help understanding this new test interpretation. Table 3 and online supplement 2 presents feedback obtained from this pilot study including how to improve test reading interpretation, participants enrolment instructions, recruitment and future use of vaginal US monitoring.

Table 3.

Feedback obtained to implement on stage 2 study

| Pilot study—lessons learnt | Future study considerations | |

| PDG test strip interpretation |

|

|

| Test strips and cervical mucus visuals |

|

|

| Vaginal ultrasound |

|

|

| Flexibility in scheduling |

|

|

| Research staff support |

|

|

| Participant diary |

|

|

| Recruitment |

|

|

bmjopen-2018-028496supp002.pdf (87.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

Main findings

Ovulation confirmation is an essential step in the investigation of infertility. This urinary POC PDG test, when used under the specified rules, had a specificity of 100% (no preovulatory positive PDG results). However, this perfect specificity was obtained at the cost of lower sensitivity. Initially, when coupled with urinary LH testing, popularly known as OPKs, sensitivity was 85% of those identified LH+ cycles (91% of all the cycles). Similarly, if women used the FAMs based on peak-fertility cervical mucus to predict ovulation, the sensitivity of the test after a peak-fertility mucus day was 87%. For the latter, it is important to reiterate that 27% of cycles were found to lack a peak mucus day. The reason for this may be that FAMs requires more user education than using simple OPKs.

Limitations and future improvements

The use of urinary POC technology to empower women to learn about their fertility has been promoted for the past 30 years.19 20 However, the use of urinary PDG technology was vulnerable to error due to the nature of the assays of urinary PDG and the variability in PDG concentration throughout the menstrual cycle.21 Traditionally, PDG concentrations have been corrected for creatinine to avoid these problems; however, this correction adds a technical difficulty to develop simple, home-based POC devices. As a result, other methods combining electronic urinary monitors and urinary volume correction are being studied to address this problem.22 In addition to these approaches, affordable, easy-to-use and versatile methods would also be welcomed by users and it is for these reasons that we proposed combining the PDG tests with a marker for ovulation prediction; either mucus or LH in the urine as solution for this problem.13

Our pilot study is the first clinical study to assess this specific test. While several women may experience false negative tests in up to 27% of cycles, for those women who obtain a positive PDG result under the above rules, they may confidently conclude that their cycle has achieved luteinisation, that is most likely indicative of an ovulation or the rare alternative clinical instance of a luteinised unruptured follicle. This would require US confirmation by future studies (stage 2). Additionally, participants viewed these tests as simple to use, non-invasive alternative to confirm ovulation, as well as decreasing risk and discomfort to women. We reached our sample size of 25 participants actively charting their cycles in <3 months simply through word of mouth and posters. This may indicate a public interest in a home-based PDG test. Improving recruitment materials and making them available online, test strip modifications by the manufacturer, using social media for recruitment and providing support for the addition of vaginal US are some of the key directions to be implemented in stage 2 study as described in detail in table 3 and online supplement 2.

Our study had some limitations. First, since it was feasibility study, it had a smaller number of participants from one single centre limiting its generalisability based on numbers and ethnic differences. Second, we purposely did not use US for ovulation confirmation in our pilot study as we lacked critical information at this stage. However, a follow-up stage 2 would incorporate this methodology. On this front, this study has provided us with an estimate of US-guided cycles needed for our stage 2 study, namely, 73 cycles would be needed in order to expect a narrow CI range between 95% and 100%.

It is worth noting that in our 2013 theoretical study which used US-confirmed ovulation, specificity was predicted to be 99%–100% and sensitivity calculations gave 72% and 92% for PDG positivity after LH positivity and peak mucus, respectively. Our limited results showed the same specificity and slightly higher sensitivity after a positive LH test. This stage 1 study, while based on a limited sample size using a packaged PDG urinary kit, may suggest that one positive test on the fourth day after either a first positive LH or peak mucus day could be enough to confirm ovulation. This hypothesis should be taken with caution and calls for additional study. It is also worth noting that previously similar comparative studies on serum and urine-excretion levels have demonstrated the important role of using urinary steroid hormonal levels to confirm and monitor the ovulatory cycle.23 A future stage 2 study incorporating interventions to address the limitations found in the pilot study and including new approaches to make confirmation more sensitive is warranted. Consideration of increasing sample size, participant diversification, multiple sites and the addition of vaginal US assessment of the cycle is need to validate this hypothesis.

As mentioned above, infertility assessment requires both prediction and confirmation of the fertile window and ovulation to provide a meaningful clinical advice to couples. While couples are well served with an education on FAMs to increase their chances to conception,24 25 confirming whether each cycle is ovulatory or not is a crucial medical information to guide further medical treatment.12 Lastly, given the differences in visual interpretations between this test and other much more commonly used fertility-related urinary tests (ie, OPKs and pregnancy), training of participants is highly required to avoid any confusion.

Conclusion

This feasibility study is the first clinical dataset that demonstrates a fully developed and novel urine test with a preliminary 100% specificity for ovulation confirmation at the expense of a lower sensitivity depending on the method to predict ovulation. While this study was not powered to test efficacy, it helped to provide information on power, recruitment and retention, acceptability of the procedures and ease of its use by the participants. Given the test preliminary high specificity, further research with larger clinical trials is recommended to both improve this technology, incorporate additional approaches to confirm ovulation. These findings represent very valuable information in the setting of providing help to women with infertility and it has also the potential to be used as an adjunct to FAMs for family planning purposes.13

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tania El Hindi for her contributions at the initial stages of the study’s protocol development.

Footnotes

Contributors: RL conceived the study. RL, MMcN-K, HN, RE and TB designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. RE performed the statistical analysis. MMcN-K and HN supervised the enrolment and participants during the study.

Funding: This study was funded by Bruyère Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was sought and granted by the Bruyère Continuing Care Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Datta J, Palmer MJ, Tanton C, et al. Prevalence of infertility and help seeking among 15 000 women and men. Hum Reprod 2016;31:2108–18. 10.1093/humrep/dew123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thoma ME, McLain AC, Louis JF, et al. Prevalence of infertility in the United States as estimated by the current duration approach and a traditional constructed approach. Fertil Steril 2013;99:1324–31. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brezina PR, Haberl E, Wallach E. At home testing: optimizing management for the infertility physician. Fertil Steril 2011;95:1867–78. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bouchard TP, Fehring RJ, Schneider MM. Achieving Pregnancy Using Primary Care Interventions to Identify the Fertile Window. Front Med 2017;4:250 10.3389/fmed.2017.00250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Heid M. You asked: do ovulation kits really help you get pregnant?. TIME Health. 2017. http://time.com/4712786/ovulation-kit-pregnant-pregnancy/.

- 6. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Diagnostic evaluation of the infertile female: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2012;98:302–7. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Fertility problems: assessment and treatment. London (UK, 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine in collaboration with Society for Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility. Optimizing natural fertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril 2013;100:631–7. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leiva RA, Bouchard TP, Abdullah SH, et al. Urinary Luteinizing Hormone Tests: Which Concentration Threshold Best Predicts Ovulation? Front Public Health 2017;5:320 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stanford JB. Revisiting the fertile window. Fertil Steril 2015;103:1152–3. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ecochard R, Duterque O, Leiva R, et al. Self-identification of the clinical fertile window and the ovulation period. Fertil Steril 2015;103:1319–25. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leiva R, Bouchard T, Boehringer H, et al. Random serum progesterone threshold to confirm ovulation. Steroids 2015;101:125–9. 10.1016/j.steroids.2015.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ecochard R, Leiva R, Bouchard T, et al. Use of urinary pregnanediol 3-glucuronide to confirm ovulation. Steroids 2013;78:1035–40. 10.1016/j.steroids.2013.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roos J, Johnson S, Weddell S, et al. Monitoring the menstrual cycle: Comparison of urinary and serum reproductive hormones referenced to true ovulation. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2015;20:438–50. 10.3109/13625187.2015.1048331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ecochard R, Boehringer H, Rabilloud M, et al. Chronological aspects of ultrasonic, hormonal, and other indirect indices of ovulation. BJOG 2001;108:822–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miro F, Coley J, Gani MM, et al. Comparison between creatinine and pregnanediol adjustments in the retrospective analysis of urinary hormone profiles during the human menstrual cycle. Clin Chem Lab Med 2004;42:1043–50. 10.1515/CCLM.2004.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoffmann MJ. FDA Regulatory Process. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/NewsEvents/WorkshopsConferences/UCM424735.pdf (Accessed 20 Jan 2018).

- 18. Colombo B, Mion A, Passarin K, et al. Cervical mucus symptom and daily fecundability: first results from a new database. Stat Methods Med Res 2006;15:161–80. 10.1191/0962280206sm437oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Djerassi C. Fertility awareness: jet-age rhythm method? Science 1990;248:1061–2. 10.1126/science.2343313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brown JB, Holmes J, Barker G. Use of the Home Ovarian Monitor in pregnancy avoidance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165(6 Pt 2):2008–11. 10.1016/S0002-9378(11)90568-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sauer MV, Paulson RJ, Chenette P, et al. Effect of hydration on random levels of urinary pregnanediol glucuronide. Gynecol Endocrinol 1990;4:145–9. 10.3109/09513599009009801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Blackwell LF, Vigil P, Gross B, et al. Monitoring of ovarian activity by measurement of urinary excretion rates of estrone glucuronide and pregnanediol glucuronide using the Ovarian Monitor, Part II: reliability of home testing. Hum Reprod 2012;27:550–7. 10.1093/humrep/der409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Munro CJ, Stabenfeldt GH, Cragun JR, et al. Relationship of serum estradiol and progesterone concentrations to the excretion profiles of their major urinary metabolites as measured by enzyme immunoassay and radioimmunoassay. Clin Chem 1991;37:838–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frank-Herrmann P, Jacobs C, Jenetzky E, et al. Natural conception rates in subfertile couples following fertility awareness training. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017;295:1015–24. 10.1007/s00404-017-4294-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Baird DD. Timing of sexual intercourse in relation to ovulation. Effects on the probability of conception, survival of the pregnancy, and sex of the baby. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1517–21. 10.1056/NEJM199512073332301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028496supp001.pdf (88.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-028496supp002.pdf (87.7KB, pdf)