Abstract

Objectives

Improving the quality of primary care is an important strategy to improve health outcomes. However, responses to continuous quality improvement (CQI) initiatives are variable, likely due in part to a mismatch between interventions and context. This project aimed to understand the successful implementation of CQI initiatives in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services in Australia through exploring the strategies used by ‘high-improving’ Indigenous primary healthcare (PHC) services.

Design, settings and participants

This strengths-based participatory observational study used a multiple case study method with six Indigenous PHC services in northern Australia that had improved their performance in CQI audits. Interviews with healthcare providers, service users and managers (n=134), documentary review and non-participant observation were used to explore implementation of CQI and the enablers of quality improvement in these contexts.

Results

Services approached the implementation of CQI differently according to their contexts. Common themes previously reported included CQI systems, teamwork, collaboration, a stable workforce and community engagement. Novel themes included embeddedness in the local historical and cultural contexts, two-way learning about CQI and the community ‘driving’ health improvement. These novel themes were implicit in the descriptions of stakeholders about why the services were improving. Embeddedness in the local historical and cultural context resulted in ‘two-way’ learning between communities and health system personnel.

Conclusions

Practical interventions to strengthen responses to CQI in Indigenous PHC services require recruitment and support of an appropriate and well prepared workforce, training in leadership and joint decision-making, regional CQI collaboratives and workable mechanisms for genuine community engagement. A ‘toolkit’ of strategies for service support might address each of these components, although strategies need to be implemented through a two-way learning process and adapted to the historical and cultural community context. Such approaches have the potential to assist health service personnel strengthen the PHC provided to Indigenous communities.

Keywords: continuous quality improvement, primary health care, aboriginal, systems approach, implementation, quality of care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used a participatory approach and mixed methods to gather rich, contextually informed data from each of our six case study sites.

This approach addresses an identified gap in the literature—that of linking the effectiveness of continuous quality improvement interventions to the contexts in which they operate.

Involvement of service providers, community-controlled peak bodies and government health departments enhances opportunities for translation into policy and practice.

Findings from the in-depth exploration with six Indigenous health services in northern Australia with a keen interest in quality improvement approaches may be difficult to directly transfer to other settings.

However, the diversity in population size, remoteness and governance models among our sites and the relationship to findings reported elsewhere suggest that our findings may have applicability in a range of underserved healthcare settings.

Background

Achieving improvement in the quality of primary care on a broad scale is a challenge worldwide, with evidence that there is a substantial gap between best practice as defined by clinical practice guidelines and actual practice.1 Success in the implementation of complex interventions to improve the quality of primary care is often patchy, with a 2016 systematic review finding that the ‘fit’ between the intervention and the context was often critical in determining intervention success, although few studies reported sufficiently on the interaction between context and other factors.2 Olivier de Sardan3 suggests that often interventions aimed at quality improvement ‘travel’ from country to country and are applied largely without consideration of the health system context, thus limiting their effectiveness.3 Primary healthcare (PHC) services are themselves adaptive systems and also operate within the larger complex adaptive health system.4

Improving the quality of PHC provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians is an essential part of strategies to overcome Indigenous disadvantage.5 Although continuous quality improvement (CQI) processes appear to be successful overall in improving quality of care in primary care,6 including in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander PHC services (hereafter, Indigenous PHC services7), there is very wide variability in response to these initiatives.8 Understanding this variability and the systems and implementation factors that affect it is an important step in improving the effectiveness of CQI on a broader scale, yet limited research in the Indigenous PHC sector has previously addressed this issue.

In Australia, in remote areas there are government health services and Indigenous-specific PHCs called Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS); these offer tailored PHC to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. However, the quality of care provided by such services, and the health outcomes achieved, vary significantly between services.8 In response to CQI, some services consistently achieve relatively high performance, apparently due to interplay between strong and stable organisations, good governance and clinical leadership,9 which together with a supportive community and policy context facilitate perseverance with participation in CQI.7 In contrast, some services show limited improvement (sometimes none), due to a range of interwoven implementation, resourcing and community contextual factors, often the inverse of those underlying high performance. A growing body of literature suggests common factors which facilitate positive responses to CQI initiatives. These include: (1) whole of organisation culture and engagement;2 10 (2) a health workforce that is sufficient, stable and skilled;11–13 (3) strong data systems;14 (4) supportive linkages and networks with the community and the broader health system;15 16 and (5) stable, long-term funding with a supportive policy framework.9 17 What is poorly understood, but so important for Indigenous services, is how these systems factors interact with the specific sociocultural and historical contexts of Indigenous communities to affect quality improvement and how variability in responses towards higher performance trajectories might be enhanced.2 18

We conducted a project to explore this variability using a strengths-based approach, to learn from Indigenous PHC services successful in improving the quality of care provided in response to CQI. This paper reports how quality improvement is operationalised at these successful (‘high-improving’) Indigenous PHC services, including the adaptation of strategies to cultural and historical contexts, and systems factors that were important in producing the outcomes.

Methods

A multicase comparative case study design using quantitative and qualitative data was employed with six case study sites in remote northern Australia and the Torres Strait. A participatory and strengths-based research design was used to investigate how CQI worked at these high-improving services and how systems factors affected CQI processes and outcomes. This design entailed working collaboratively with the high-improving services (staff and service users) drawing on their strengths and knowledge to contribute to understandings of CQI and the social and cultural dynamics of the context. This is an appropriate design to investigate systemic health system patterns surrounding CQI in the dynamic social setting of Indigenous PHC services.19

Patient and public involvement

This study arose and questions were refined from discussions within a community of practice of Aboriginal health peak bodies, services and researchers. Service representatives and community members were included in a learning community, to guide and steer the conduct of the project. Obtaining patient feedback about the success of quality improvement initiatives was critical to the project, and interviews with services users and ‘boundary crossing’ local health workers and community members were obtained. Consistent with our participatory approach, feedback visits occurred to each community to report findings from each site back to staff members and community members.

Study population and case sampling

‘High improving’ services were identified by calculating quality of care indices for Indigenous health services participating in the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease (ABCD) National Research Partnership. These indices were based on the delivery of services against recommended guidelines for service provision during yearly audits in four areas: maternal health, child health, preventive health and chronic disease (type 2 diabetes mellitus). Health service performance was calculated by deriving the proportion of guideline-scheduled services delivered out of the total number of scheduled services for each audit tool in each year of participation. Trends in performance over time were examined with services categorised as ‘high-improving’ if they showed consistent ascending performance over at least two of the four audit tools over three or more audits. Full detail on the categorising method is provided elsewhere.20 Six health services that met the inclusion criteria of continuous high improvement and included a spread of regional and rural services and mix of government of services and ACCHS were selected and agreed to participate in the current study.

The characteristics of these six Indigenous health services categorised as high-improving in this study are described in table 1. All health services are located in northern Australia and five are located in communities with a predominantly Indigenous population. Most of the services are situated in remote locations with relatively small populations, fewer than 1000 people, but two are in larger rural ‘cross-roads’ towns with a larger, more mobile population with services offered to communities across the wider area, often people living in very remote parts of northern Australia. Three of the services are government-operated health services which means they are governed and funded by the health department of the relevant state. Two of the services are ACCHS which means the services are operated by the local Aboriginal community to deliver holistic and culturally appropriate healthcare to the community which controls it (through a locally elected board of management21). One of the case studies is a health partnership between government-operated health services and an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. The process for undertaking CQI audits and completion of system assessment tools (SATs) differed across the high-improving health services (table 1). Some of the services adopted a formal approach which involved all staff members, while in other services they were facilitated by an external team with varied involvement from the health service staff.22

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating Indigenous PHC services

| Site | State | Governance | Rurality | Population | % identify as Indigenous | High improvement in | Conduct of CQI audits and SAT tools |

| 1 | QLD | Government | Remote | ≤500 | 92 | T2DM Maternal |

|

| 2 | QLD | Government | Remote | ≤500 | 99 | T2DM Preventive Child Health |

|

| 3 | WA | Government/ACCHO partnership | Remote | ≥1000 | 66.5 | Maternal T2DM |

|

| 4 | NT | Government | Regional | 501–999 | 23 | Maternal Preventive |

|

| 5 | NT | ACCHS | Remote | 501–999 | 93 | Preventive Child Health |

|

| 6 | NT | ACCHS | Regional | ≥1000 | 100 | Preventive Child Health |

|

ACCHO, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation; ACCHS, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service; CQI, continuous quality improvement; DMS, Director Medical Services; NT, Northern Territory; PHC, primary healthcare; QLD, Queensland; SAT, system assessment tool; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; WA, Western Australia.

Data collection

Four data sets were used for the case studies: (1) existing audit and systems assessment tool data; (2) qualitative interviews with health staff, service users and external stakeholders; (3) health service and workforce questionnaires completed by local managers; and (4) non-participant observation by members of our team as recorded in field notes. Data were collected between 2015 and 2016 during two or more visits to the sites. Multiple data sources were used to enhance data credibility and develop a more holistic understanding of the high-improving services.23 Interviews with local and visiting health service staff and managers and regional managers explored the impact of contextual factors and the interplay of systems factors (such as leadership, governance, resourcing and workforce) on quality improvement in the service. Service users were asked about their history of use of the service, what they thought about it and the staff, and improvements they might like to see. Informed written consent was sought from all participants.

Analysis

The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. The analysis of qualitative interviews was completed abductively,24 which is an inferential creative process of producing novel concepts in this study, about health system and implementation factors that support CQI in Indigenous health services. Within-case analysis was conducted first. Transcripts and field notes were read by multiple team members and then coded by three team members into NVivo qualitative data analysis software V.11 (QSR International) for each case. Codes were derived deductively using the interview topics and were used consistently across the six cases. Then, within each case, codes were amalgamated into themes developed inductively, identifying underlying meanings apparent in codes. The themes for each case were visually displayed at the macro, meso and micro levels and reported back to the health service team to refine the descriptive model and conclusions.

Across-case analysis involved aligning similar and different themes for each case in a visual display. Then similar themes across cases were analysed together to determine the commonalities and produce new themes. Themes that were unique to one service were retained. Concurrently, theory and concepts about quality improvement, health systems functioning, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community participation were reviewed to see if findings concurred with existing concepts or whether new ones could be added. Discussion of both within-case and cross-case findings took place with service partners (both individually and jointly) to assist with interpretation.

Main findings

A total of 134 interviews were conducted across the six case study sites (table 2).

Table 2.

Number of interviews conducted in each case study site (n=134)

| Site | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Total |

| Health service staff | 7 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 54 |

| Health service user | 9 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 51 |

| External stakeholder | 0 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 24 |

| Total | 16 (5)* | 14 (5)* | 25 | 20 | 28 | 26 | 134 |

*A total of five regional stakeholders with common responsibilities for sites 1 and 2 were interviewed.

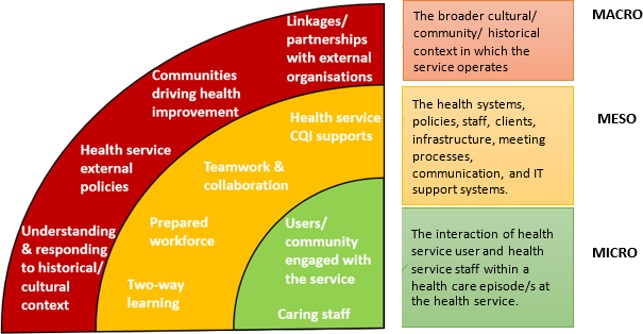

Analysis of the case studies revealed a complex interplay of systems factors that were individualised, reflecting the context and circumstances of the service (table 3). Some of these factors, common across most services, are consistently reported in the literature and some are novel. At the macrosystem level, the first group of factors commonly reported included: (1) linkages and partnerships with external organisations; and (2) supportive external health service policies. At the mesosystem, or health service level the common factors were: (3) health service CQI supports; (4) teamwork and collaboration; and (5) prepared workforce. While at the microsystem level the factors were: (6) consumers engaged with the service; and (7) caring staff (figure 1). The novel factors found in most services at the macro system were: (1) understanding and responding to the historical and cultural context; (2) communities driving health improvement; and at the meso level: (3) two-way learning between health professionals and communities.

Table 3.

Summarised within case analyses: factors affecting continuous quality improvement (could be supplementary material)

| Level | Theme | Site (1) | Site (2) | Site (3) | Site (4) | Site (5) | Site (6) |

| Macro | Linkages/partnerships with external organisations | ‡ | * ‘So (name) comes around quite frequently and gets an update on health because he’s on the Hospital Board. He goes around all the different agencies in the community for updates so he’s very proactive in that way.’ |

* ‘The partnership recognises that other agencies also contribute, so there is Mental Health, there is (name) Paediatrics that provides services, there’s also United First Peoples of Australia who provide services.’ |

* ‘You know we need really good relationships with services like (ACCHS) to sort it out. I know we’ve got some students that have organised with their Clinic to be able to get their medication while they’re here.’ |

† ‘AMSANT did one of their collaborative workshops in Katherine and the focus was on anaemia…I know that we’ve shared data with the ABCD partnership stuff.’ |

† ‘There are very good relationships with stakeholders in Central Australia ……. from clinical working on a daily basis, we need to strengthen those relationships.’ |

| Supportive external health service policies | † ‘So just because of the stability and the belonging and the Health Workers, in the communities, it’s more ideal to invest and give them the appropriate training.’ |

† ‘…there’s a huge shift in the way Primary Healthcare is delivered and it’s coming from the top. Before it was more acute. Executives have finally realised that…’ |

* ‘There was a really concerted effort to try and get people on fixed term contracts rather than agency. Or swap them over from agency to fixed term.’ |

* ‘We have received a lot of support from central – from N.T. Health. We are able to access the CQI coordinator if we need to, to get some advice.’ |

* ‘we probably find a lot of our support from the N.T. Health Government as well.’ |

‡ | |

| Understanding and responding to historical and cultural context | ‡ | * ‘people need to, before they go and talk to people, they really need to sit back and understand their ways first. They need to know their audience.’ |

* ‘Find out the story of the people that you’re working for… that’ll give you a rough indication of where things are… It gives you a bit more understanding of them.’ |

‡ | * ‘We have a pretty big focus on cultural safety and cultural security in the organisation. People get hammered at cultural orientation. If an issue arises we’ll nip it in the bud pretty well straight away.’ |

* ‘I’m a full supporter of Aboriginal Health Services and as a community we need to get behind them …Our health is not improving and in fact… it’s actually gone downhill since the intervention in the Territory’ |

|

| Community driving health (care) | ‡ | * ‘The Health Committee in the community, introduced that because that was where we needed to be working and that was our support system. We’d all agree that we’ll be coordinating and that was the beginning of the direction of our future health’ |

‡ | ‡ | * ‘consumer input into the governance of care …that makes a big difference…but anything new that comes to us is provided in terms of a cultural and security framework and…that does help with engagement in care and participation, and some of the self-management stuff.’ |

‡ | |

| Meso | CQI systems and supports at health service level | ‡ | † ‘They do yearly checks on a few things and the healthcare staff here are quite good at monitoring – controlling who’s coming in and who’s going out.’ |

‡ | * ‘The CQI is something which is best done when someone’s interested in it and hopefully passionate. …when they get the feedback that they’re improving things, they can see the difference that it’s making.’ |

* ‘So we have quite a tight structure around quality improvement. We do actively have a quality approach to the way that we deliver our health service and we actually announce that- we say that.’ |

* ‘We have embraced the process a lot more than what was in place before then. It’s a regular process now’ |

| Teamwork and collaboration: shared focus | * ‘We support each other.' ‘We’re pretty tight as a unit.’ |

* ‘It’s the communication here, it’s just really open and (lack of experience) isn’t held against me so to speak. I suppose coz I’m fresh eyes as well. And I have been asked you know, ‘if you see anything that you think is missing.’ |

* ‘We are a team and using the computer system while you’re triaging a mother for …pain, ‘oh look she’s overdue, 6 week check.’ ‘Let’s just have a look at baby in the pram. He’s 2 months overdue his needles!’ That’s the kind of things that we’re trying to strive for.’ |

* ‘They’ve got staff who really understand about how to deliver primary healthcare programmes and they really think about and they have to think hard about how they do that for both an Indigenous population and a non-Indigenous population’ |

* ‘When we think about why are we here? We’re here for our people out in our communities and how do we provide the service best we can… we respond to their needs and wants.’ |

* ‘They would work with a Health Practitioner usually…So they got to work in ways that they don’t normally work. So there was all this team-building type stuff, you know, and relationship type stuff, in a different way, which was good.’ |

|

| Prepared and stable workforce for CQI | * ‘it’s better to have one that’s here coz they- they build a rapport with the locals and they get to understand a full history of the patient, which is good.’ |

* ‘The Health Service runs smoothly because the continuity has always been there. So (name) knows the system and what kind of programmes to deliver.’ |

* ‘I honestly think local personnel and a fresh outlook has made a big difference (to the partnership) and that’s continuity. Stopped this…churn of agency through this hospital.’ |

* ‘The advantage they have is that they have a more stable staff and going right through from their reception staff to their clinical staff.’ |

* ‘I think the benefit that we have here is a very stable Leadership Group. So all of the people …have been here for at least 5 years…and some of us for ten. I see in terms of staffing, I see stability now that I’ve never seen in the past.’ |

* ‘I think that they have consistent staff which makes a difference. A lot of the other health centres that you go to every time you go there’s a different staff member there that makes it difficult. So having consistent staff is one of the big keys.’ |

|

| ‘Two way learning’ for CQI (Indigenous culture and health) | ‡ | * ‘I always like to use the word tuning in – tuning in to people. Different frequencies. Listen to them. Understanding them and I can use my knowledge with their knowledge to bring a level of half understanding between (us).’ |

* ‘What was working really well, through the partnership is the Family Approach programme. The first step was to introduce the doctor to the traditional owners of that place, then meeting the chairperson, explaining the Family Approach to them and the Council and the community.’ |

‡ | * ‘We go out yearly and hold open community meetings…Management staff will go out, put ourselves in front of the community…give an update on what we’ve done for the last twelve months…open that up to the community and our performance review begins at that point. You tell us from a grass roots perspective, …and if we’ve got challenges then (they) will certainly let us know.’ |

* ‘I think having the Aboriginal health workers on board? It’s that two-way learning and I’m a believer of two-way learning and that is between health workers and the doctors.’ |

|

| Micro | User/community engaged with the service | * ‘We have regular women’s nights where we can promote friendship, getting together and support.’ |

* ‘People seem to trust and follow-up on their own health, instead of people having to go out and collect them, which is quite interesting as well. Like the health behaviour here is I think a bit different than the type of places I’ve been’ |

* ‘One of the ‘hooks’ for Aboriginal people to get involved in the health services was the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health checks – just around the engagement with the families getting families in, getting them engaged.’ |

* ‘The people that do come to the clinic, they come when they’re called in general and they engage. They try and do what you ask them to do. They’re very actively managed by the clinic in terms of getting them in here and they get good service when they come in…and they come back.’ |

* ‘We have a client population that is I suppose, regularly interacting with the health system.’ |

* ‘I feel comfortable and every time I come here, everybody’s just laid back. Then they’ve got all these different little changes that happen now and then with the office and stuff it makes you feel really - could you say, ‘at home’.’ |

| ‘Going the extra mile’ and staff caring, commitment | * ‘They go that little extra mile I think to do those extra things like the afterhours events.’ |

* ‘(name) has been there for a number of years and has gained the trust of many community members. (name) is part of community.’ |

* ‘You know, it’s respectful and they listen to you if you got a problem. You know, a lot of health centres don’t listen to their community people when they go in and some are very hard to talk to, but you can go up any time and talk to them about anything if you need to.’ |

* ‘I had bleeding so we rang up the clinic and a Health Worker she got a hold of the nurse. Well by the time I got to the clinic, she rang and apologised. She even pulled her kids out of the bath to get over to me. So I mean that’s real dedication.’ |

* ‘…well they’re doing everything all alright. They get along with the community people. They go around, they have a yarn to people. If they need to chase someone down, they go and do that.’ |

* ‘I enjoy coming in here you know. Have a talk with them and that. They’re always happy, no sad faces or anything. They always greet you with a smile. And they ask me questions too you know. Where they’re going wrong.’ |

*Clearly present.

†Present to some degree.

‡Not clearly present.

ACCHS, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services; AMSANT, Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance, Northern Territory; CQI, continuous quality improvement; N.T., Northern Territory, Australia.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing continuous quality improvement (CQI) at high-improving services.

We also report on the perceptions of interviewees about the reasons for high continuous improvement at the service. The operationalisation of ‘two-way learning’, although it was not named as such, was found in three sites where there were high levels of interaction of the cultural and historical Indigenous context with the strategies for CQI.

Each of these findings will now be described in turn.

Factors influencing CQI at high-improving services consistent with existing literature

Macro-level factors: linkages and partnerships with external organisations

High-improving services linked with external organisations to enhance the healthcare they were providing, for example, attending regional forums as part of the CQI support system. This occurred in all the services although processes differed. Health professionals recognised that they did not operate in isolation so engaged with local organisations and other health service providers. Some linkages were informal or ad hoc based on local priorities and needs, and others were more formal partnerships.

Where the different organisations across the Territory come together and we share data and we share experiences, and quite often people have got really good processes … it turns out we’re pretty much all addressing the same issues… Sometimes one of the other AMSs have started to deal with it [a problem] and make improvements that are effective. And if you don’t talk to them, you don’t know. (Health service staff, site 6)

Working together was important for implementation and linked to a shared motivation or a ‘collective intent’ to improve the healthcare of the communities services were working with. Some jurisdictions had a policy impetus that helped drive collaboration. However, the strongest theme was ensuring health service users and the community received timely and appropriate care to improve outcomes. Other reported benefits of working with external organisations included sharing expertise, information and improved relationships with clients and community.

And it shows – the clients are getting better outcomes. As an example, we’ve had difficulty with patients that can’t get dialysis here…We don’t have the capacity to just start plucking money out of anywhere to send individuals back for dialysis. Neither do [service name] but between us being very creative about who’s going to [local town] what services are travelling between [local town], how we can utilise whatever’s happening between our three services and in the community. (Health service staff, site 3)

Supportive external health service policies

Health service policies from the state level (ie, Queensland Health, Western Australia Health and Northern Territory Health) and national level health departments provided an overarching framework within which the health services operated. In some jurisdictions, external health service policies at the macro level were supportive of CQI. In supportive contexts there was provision of leadership through the appointment of regional CQI coordinators working across multiple services; training for health service staff with funding to attend CQI workshops; and workforce policies and tools to facilitate CQI in the health services.

We have received a lot of support from central – from NT Health. We are able to access the CQI coordinator if we need to, to get some advice… We have at least an annual meeting for the CQI Facilitators, where they’re developing up specific skills that they can then teach to the teams that they work with. (Health service staff, site 4)

There’s the concept of the Traffic Light Report that’s coming out now …We also noticed that we’re making improvements if we look at the previous three or four reports and the colours are changing! So that was a really good thing to see and even though things aren’t great in all areas yet, the fact is we’re trending up in morale. (Health service staff, site 4)

Health services located in one of the jurisdictions where there had been less consistent central leadership and support had generated local solutions for CQI.

I think we’re doing a lot of good stuff that is not really captured…and when I start talking about things, ‘what have you done?’ ‘How can we do this better?’ ‘Oh no, no, we’ve already got this process and that process and we’re doing this.’ And it’s fascinating to see them light up when they realise that they are actually doing a lot of improvement and they didn’t see it as such. (External stakeholder, Sites 1 and 2)

Meso-level factors: CQI systems and supports at health service level

Having appropriate systems and support at the health service level was vital for CQI in relation to embedding CQI into daily activities. Interviews with health service staff from high-improving services indicated that effective CQI systems and support included: information technology systems integrated with the electronic medical record for recalls; templates to assist people to reliably and objectively record data; regular production of quality reports and audit data; and team meetings with a focus on quality improvement.

I suppose the greatest thing, all your notes are in one place - everyone’s notes. So it opens it up – doesn’t matter where they turn up. Coz everyone’s seeing the same screen (Health service staff, site 6)

All services had CQI systems in place but how these were implemented differed slightly. In some health services it was very structured and standards driven.

Whereas for us, our core business is acute care and our continuing quality improvement is set at a national standard. (External stakeholder, site 3)

In other services, formal systems ran in parallel to very practical and community-driven systems. For example, one community-driven process ensured that yearly health checks are conducted in the month of the resident’s birthday. This spread the clinic’s workload across the year and ensured coverage while making health screening and vaccination routine, non-intrusive and efficient.

CQI systems and supports were viewed positively and promoted a routine and culture of CQI. Some health service professionals reflected on CQI in terms providing appropriate and timely care.

What is particularly effective is to be able to effectively gather statistical information which is what we’re using and so that’s really good, to be able to press a few buttons…I do a lot of recalls and the nurse would do a print out of all our recalls and I’ll follow them [clients] all up and try and get them in. (Health service staff, site 4)

Teamwork and collaboration: shared focus

A striking feature of these high-improving services was staff commitment to working together towards the same end—improved health for the clients and the community. This was expressed in a variety of ways. Perhaps the most obvious was ‘We all know why we are here', meaning that all staff at the health centre had a shared commitment to improving health outcomes. Furthermore, evident in the high-improving services was the connection between teamwork and continuous improvement and involving the whole team in CQI.

And you could just see a lot of the junior staff really listening and starting to switch on and go, ‘okay. So there’s more to me than just answering the phone'. And, ‘this is how I’ve contributed in this area and that area…and this is our actual purpose. This is what we’re really here for. (Health service staff, site 5)

In several services, staff were perceived to be ‘passionate about quality’, meaning that opportunities for improvement were sought out and embraced. Importantly, these passionate staff were able to inspire others towards the joint intent to improve the health of individuals and the community as a whole. ‘How can we improve the community’s health?’ was a mantra in one service and others shared similar themes.

The CQI is something which is best done when someone’s interested in it and hopefully passionate. And we do have that fortunately, but when someone actually likes it and particularly when they get the feedback that they’re improving things, they can see the difference that it’s making. (Health service staff, site 4)

Building teamwork for CQI required leadership to drive and facilitate activities such as team meetings, shared decision making and support networks. One health service described their strategy of bringing together groups of people as teams to do the CQI audits. Another health service brought together remotely located health professionals to discuss CQI at weekly teleconferences.

But you know, we have that collaborative team approach across everything. We also collaborate strongly with our remote clinicians so we give them the opportunity to be involved in decision-making around quality so they’re engaged every Friday mornings so basically like a team meeting, with a quality focus. (Health service staff, site 5)

In many of the services, CQI was embedded in how they operated and was everybody’s business. The comment below illustrates one service’s team approach, searching for ways to improving and analysing data in a way that guided areas for improvement.

Yeah so it actually becomes quite good and everybody gets involved and has a look. If something isn’t working properly you fix it… We look at it and work out what we need to change from spreadsheets for chronic disease, where your shortfalls are. ’Coz if you don’t do that sort of stuff, you can’t actually see what the problem is. We had a session a few weeks ago with spreadsheets, graphs and pie charts, and even the doctors are surprised at what they haven’t been doing. (Health service staff, site 4)

Two more reasons frequently expressed for working as a team were: (1) the enormity of the task to improve Indigenous health and pressure to get it right because it mattered to them personally. As stated by one staff member, ‘You know this is chronic disease data to you’ I said, but to me it’s my families (Health service staff, site 3); and (2) the valued mix of skills held by Indigenous staff and the importance of balancing those held by non-Indigenous staff.

It’s good to see the Indigenous people really involved in the organisation. It makes a lot of Aboriginal people feel more relaxed - more comfortable with using the service. (Health service staff, site 6)

Thus it was a collective intent and action rather than just an individual attribute that acted as a motivator supporting the development of shared goals and objectives and improved health outcomes for service users.

We’ve structured everything so everyone’s involved. So likewise with primary healthcare governance – everyone’s involved and that was always… But it’s always with a collaborative approach if that makes sense…. (Health service staff, site 5)

Prepared and stable workforce for CQI

Interviews with health professionals and stakeholders revealed a pragmatic understanding about requirements for the health workforce. Characteristics of a prepared workforce included stability; appropriate orientation; a mix of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal staff; trusting relationships, and supportive leadership. Many of the services had long-term staff and those stable staff had developed deep knowledge and understanding about the communities they were working in and with that appropriate ways to deliver PHC.

The advantage they have is that they have a more stable staff and going right through from their reception staff to their clinical staff. They’ve got staff who really understand about how to deliver primary healthcare programmes …they have to think hard about how they do that for both an Indigenous population and a non-Indigenous population. (Health service staff, site 4)

These comments suggest that staff stability enabled trusting relationships and embeddedness to facilitate improvement in healthcare, perhaps reflecting also an understanding of the care system and having the maturity and confidence to make small changes for the benefit of service users. However, striving for workforce stability was a challenging space for most services, so some had developed a range of pragmatic strategies to increase preparation and support.

…it’s a challenging space and although we strive for this stability, the trade-off is you know, if people stay too long that’s a challenge as well. And you kinda find the balance between having a really well prepared workforce and being able to support that really well prepared workforce and then having a workforce that are tired and a bit disgruntled and are struggling in this space. (Health service staff, site 5)

Linked to a stable workforce was the mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff. Some health professionals observed that Indigenous staff were likely to stay longer as they were locals living in the community/local area. Locally based Indigenous staff were knowledgeable about the community and local culture, and this knowledge was respected. In addition, the retention of locally based Indigenous staff gave the community a sense of ownership and users of the service felt that staff knew the community well.

And our Aboriginal staff stay a lot longer because they’re local. …The fact is there are a lot of locals working here - that’s a good thing too. It is their resource base within the community. It also gives the community a sense of ownership over the Health Services as well, knowing that they’ve got locals working in there. (Health service staff, site 6)

User and community engagement with the service

User and community engagement with the health service was frequently cited as influencing how CQI was enacted across the participant health services. Health service users commented on having a good relationship between the health service and the community it served.

…well they’re doing everything all alright. They get along with the community people. They go around, they have a yarn to people. If they need to chase someone down, they go and do that. Everything’s going good. (Health service user, site 5)

The mechanisms reported and observed for health services engaging with users and the community varied. For some services, these related to engaging in the monitoring of their health at both the individual and group levels. In other health services it was related sitting down together with community and asking the question ‘How do we improve services?’

We go out yearly and hold open community meetings. So us as management staff will go out, put ourselves in front of the community um…we’ll give an update on what we’ve done for the last twelve months and then we open that up to the community and our performance review begins at that point. You tell us from a grass roots perspective, what we’ve been doing right and what are our challenges and if we’ve got challenges then (they) will certainly let us know…and at that grass roots level, it’s about sitting down and talking. (Health service staff, site 5)

Other comments from health professionals focused on the importance of developing a connection with community and their culture. All services worked with or in their communities and drew on strong place-based family connections. These connections supported CQI when there was open communication between health centre staff, community members and other key people about community views, aspirations and health issues.

One of the ‘hooks’ for Aboriginal people to get involved in the health services was the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health checks – just around the engagement with the families getting families in, getting them engaged. It was going in the right direction and it is working on a large community development program- because people say family health but I see it as community development.…you gotta have that engagement side of things kind of grounded down I think. (Health service staff, site 6)

Microsystem factors: ‘going the extra mile’ and staff caring, commitment

This theme was characterised by health service users as getting personalised service from health professionals with health service staff going the extra mile. Users of the health service commented that the personalised service made them feel comfortable and safe, and fostered a trusting relationship with the healthcare provider.

I feel comfortable and every time I come here… they’ve got all these different little changes that happen now and then with the office and stuff it makes you feel really - could you say, at home. (Health service user, site 6)

In all services, clients acknowledged the hard work that staff put in. One interviewee described this as ‘going the extra mile’. The commitment of staff to improve the health of the communities was also evident from interviews with health service users. Service users described health service staff as ‘taking their duty of care seriously’ and being proactive and supportive.

They go that little extra mile I think to do those extra things like the afterhours events….The staff always try their best and to help you out. They’re on call so if you need to see them after hours they’re quite happy to do that….Most of the ones that we get here genuinely care for people and it’s more than just a job. (Health service user, site 1)

Overall, one important factor that service users and those people external to the service noted was the trusting relationships that had been established between service users and health professionals.

We have rare, very passionate committed, hardworking [names] that worked out here. And the fact that if you have the same person and the community get to know that person, they get to trust them, they build up that [trust]- which we know takes a while in Aboriginal communities. (Health service staff, site 3)

Novel factors contributing to CQI

Along with the factors that are well known to assist in implementing CQI were three factors that are less frequently reported on but were fundamental in these Indigenous communities. These were: understanding and responding the historical and cultural context in which the service was located; ‘two-way’ learning between health professionals and communities; and communities driving their health.

Macro level: understanding and responding to historical and cultural context

The importance of culture and history of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people associated with the health services cannot be underestimated and was made explicit during interviews at three sites.

Understanding culture involves understanding the ways things are done, the importance of relationships, how to exchange ideas, how to pass news and how the family systems function. All these aspects are fundamental to health improvement. It was thought that 'people need to, before they go and talk to people, they really need to sit back and understand their ways first. They need to know their audience’. (Health service user, site 2)

The historical backdrop includes the history of colonisation, the history of the establishment of the ‘community’ and from a historical perspective, the way in which health services have been provided. A staff person at one of the centres thought that understanding the history of the community in which the health service was based was fundamental to quality health service delivery.

[to understand our effective health service delivery] I like to go back to history. I think it’s related to the history of the island – the people who ran the islands and the people that I’ve known all these years that have functioned in the ancestral histories and backgrounds. (Health Service Manager site XX)

With regard to the importance of culture one Indigenous health practitioner put it this way.

Our culture is our foundation here. It - you go out of your bounds you know - morally inside you don’t feel right. I mean with [community controlled health service] I think they understand that with most of the Board Members they are our family as well. (Health service manager, site 5)

This person referred to the strength of the foundation of culture and inducting practitioners into this approach. 'We have a pretty big focus on cultural safety and cultural security in the organisation. People get hammered at cultural orientation. If an issue arises, we’ll nip it in the bud pretty well straight away'. (Health service manager, site 5)

In another service the rule of culture was referred to as underpinning all aspects of life including healthcare.

the rule of culture is vitally important ’coz it’s everything I guess… culture is pretty much our belief. Bottom line. What we believe and you can’t negate culture from anything that happens …the important thing is people understand those beliefs and how do we best balance those things in a way that will be productive going forward. (Health service user, site 2)

In this context, maintaining a deep understanding of their community and clients was integral to how services operated and came from motivations to improve care for clients (community) and improve health outcomes. The embeddedness in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures in these high-improving health services was reflected in how they approached engaging with service users and the wider community.

Find out their story because that’ll give you a rough indication of where things are with these people that you’re working with. (Health service user, site 3)

Meso level: ‘two way learning’ for CQI

A second factor about which there is little knowledge in the CQI literature is ‘two-way’ learning, perhaps because it reflects more of a process. Health service staff (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) that were more responsive to the historical and cultural context talked about how they integrated their knowledge about effective healthcare and CQI processes with Indigenous community family sensitivities, obligations and traditional ways. This was described by an Aboriginal staff member as ‘two way’ learning. In several of the services, Indigenous cultural knowledge was blended with health professionals’ expertise.

Well I think having the Aboriginal health workers on board. It’s that two-way learning and I’m a believer of two-way learning and that is between health workers and the doctors. At the moment we have a good quality number of doctors as well. The health worker numbers varies - I’ve only got four in the clinic but they do the best to their ability and sometimes they get highly strained and stressed. (Health service staff, site 6)

Another non-Indigenous staff member was able to describe two-way learning that was practised in the health centre that this person was associated with.

I always like to use the word ‘tuning in’ – tuning in to people. Different frequencies. Listen to them. Understanding them and I can use my knowledge with their knowledge to bring a level of half understanding between [us]. (Health service staff, site 2)

Two-way learning requires a great deal of sensitivity among ‘mainstream’ health professionals. One health professional describes some of the challenges in terms of genuine engagement in two-way learning within a Western mainstream environment.

We [health service] want to employ them because they’re local. They know the language, they know the culture. But then once they get in there, they just become more or less a lackey and they’re expected to work within the mainstream way of doing things and I think that makes it very difficult for an Aboriginal to excel – especially in a mainstream environment. (Health service staff, site 2)

Macro level: community driving health (care)

There were instances in two different services of communities explicitly driving their healthcare. In one location this occurred through a formal structure—the health committee with membership of health centre staff, staff of other organisations, community leaders and citizens. The committee depended on relationships and networks built around trust and shared intent to improve the communities’ health. In this case, the relationships were long-standing. It also depended on a ‘whole-of-community’ approach to health that was integrated into daily life. ‘Serving our people’ was a theme that ran through stories of healthcare and of whole of community involvement. The comment below from a service user describes how participation in the health committee has had a positive impact in terms of community taking control of their own health.

This is a [state department] clinic, but it is on [location] – it is our community. So the focus on community taking control of their own health is something we’ve tried to do; so we’ve come a long way to where we are. I’m glad that it’s evident and it shows how well we function. (Health service user, site 2)

Another example of communities driving health was the implementation of an Indigenous model of healthcare for chronic illness, called the family approach. It involved considering the family and community as the unit of care rather than the individual.

…the family approach model requires the involvement of the whole of the primary health team and the community in - I guess probably not a clearly expressible fabric of interaction. But perhaps the essential component of it is around a health service agent and in this case it’s been the family general practitioner (GP). A health service agent who engages with a broader family unit so it will be the oldest in the community and their siblings and partners and their children and siblings and partners and their children and siblings and partners. (External stakeholder, site 3)

The explicit motivation for the introduction of this alternative approach to healthcare was to improve Indigenous health, particularly around chronic illness. It was energetically driven by an Indigenous manager of an Indigenous health service with strong links with the community.

The perceptions of staff and service users about why the services were high performing

Prior to the interview conclusion, participants were asked why they thought their service was continuously improving. Overwhelmingly the responses coalesced around the calibre of the staff at the services; their professionalism, energy, commitment and stability. In each of the services, people gave staff actions in CQI as the reason for high continuous improvement, persistence in follow-up, enjoying the challenge of providing a ‘decent level of care for people’ and staff dedication to managing a challenging job.

I think they do a challenging job, with the resources they have. The staff they stick it out. ’Coz if someone’s really sick, the only way off is by helicopter. And it’s only the one chopper and if they’re busy, they may not get here. (Health service user, site 1)

In terms of insights, why we improved so much –we have very good staff. (Health service staff, site 5)

I’d have to go back to my colleagues [to give the reason for improvement] – they’re pretty dedicated. (Health service staff, site 3)

Another theme, but less frequently mentioned was the engagement of the health service with the community.

But they also engage well with the community and they have the trust of the community and that makes a big difference… they’re also pro-active in… engaging the community with healthcare. (Health service staff, site 1)

Finally, having a supportive environment for CQI, again linked to aspects about the staff, and being part of a well-functioning team was said to be related to high levels of continuous improvement.

I think a supportive environment is good…and everyone participating and everyone being a team player and…everyone takes responsibility so it’s just sort of doesn’t fall to one person… so just keeping it supportive and…and everyone’s responsibility. (Health service staff, site 4)

Discussion

This project explored in detail how CQI was operationalised at six Indigenous PHC services classified as ‘high-improving’ services in response to CQI audits. Consistent with health systems thinking there was interrelationship and interdependence of components including policies, technical support systems, service providers and users.25 While these services were distinctive in the details of how they operated, there were also common factors in how they operationalised CQI. Common themes among the services align with those previously reported and with existing chronic care models, particularly those at the mesosystem or health service level: CQI supports and systems within the health service, teamwork and collaboration (including supportive leadership); and a stable and well-prepared workforce. Adding to our conception of how CQI works in practice are some novel themes not often reported on in the literature. These are: (1) embeddedness in the local historical and cultural context; (2) two-way learning between community and health professionals for CQI; and (3) the community ‘driving’ health improvement at the local level through joint planning, monitoring and implementing new Indigenous approaches to healthcare. Attention to these less tangible elements introduces additional complexity to how quality might be defined for healthcare providers working in Indigenous health.

The finding that cultural embeddedness and responsiveness to the historical and cultural contexts was a hallmark for these high-improving services is important for two reasons. First, it confirms the importance of community-control or strong community engagement in health services in Indigenous communities and provides a rationale for state run or private practices to embed services in the cultural context. Second, the current move within the Australian context to include a component of community feedback in quality assessment and accreditation is not comparable in either intent or scope with what is expressed as cultural embeddedness by respondents in this project.

Services selected for case studies included both community-controlled health services and those provided through government services. Previous quantitative analysis by the project team demonstrated that a pattern that defined a ‘high-improving service’ was not simply explained by governance model, community size or remoteness.20 The model for community-controlled health services has cultural embeddedness and mechanisms for responding to community input at the core of their existence (although in practical terms how effectively this is operationalised can vary21). However, this study suggests that cultural embeddedness or responsiveness is fundamental for all services that aspire to offering high-quality care to Indigenous people, and that government services can also establish mechanisms (formal or informal) for seeking direction from Indigenous community members and ensuring mechanisms for meaningful input into the operations of the health service.

Closely related to the finding about the importance of embedding CQI in the Indigenous cultural and historical context is the concept of ‘two-way’ learning. Our participants, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, reported on their understanding of ‘two-way’ learning as a melding of health professional technical knowledge with a deep understanding and respect of the community’s customs, rules and relationships. This was reported as ‘tuning in to people’.

This is a very different concept than that of ‘community capacity building’ which is regularly referred to in health systems strengthening.26 Two-way learning has no presumption that it is the health professional that is doing the capacity building and the community that is having their capacity built in order to participate.27 The dominance of Western-centric models of health and healthcare requires that for true two-way learning there is an emphasis on health professionals trying to see outside their own cultural frameworks. As Makuwira28 puts it, because of the strength of Western ways of doing things we need to develop appropriate mechanisms through which a middle ground can be achieved, that is, a give and take between health system personnel on one hand, and Indigenous communities on the other.28

The other novel concept that emerges from our study is that of the community driving healthcare. We note that health systems thinking includes the population that the health system serves.29 The component of community is not perceived as a powerful actor influencing implementation of CQI in the published literature to date. Nonetheless, it is not uncommon to observe so-called ‘activated’ communities powerfully solving health issues through planning, devising alternate programme or advocacy, especially in association with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs).30 Capturing the concept of communities actively driving their health, usually in association with trusted health professionals, might be better done through using the term co-production; co-production where equal and reciprocal relationships between professionals, people using the services, their families and their neighbours underpin public service delivery.31

The findings about the importance of understanding culture, two-way learning, and community driving, were not among the factors staff reported on when we directly asked health centre staff and users their perceptions of the reasons for high performance. Perhaps this could be associated with the mental maps held by participants of their CQI health system elements and the interaction.32 Alternatively, it might be that in these high improving services there is implicit knowledge of the sociocultural context shared by staff, which is not openly discussed but rather based on deeply ingrained understandings and ways of working.

Implications of study

These findings have implications in terms of practical interventions to strengthen implementation of quality improvement at a broad range of Indigenous PHC services. Our findings suggest that there is now a need to broaden attention to include the broader organisational and interpersonal factors important in achieving change, with services. According to our data, key among these factors is harnessing a shared interest in CQI among a wide range of staff, managers and community members through their joint interest in improving health outcomes for the community. This genuine and deep motivation about real people that underpin the data and figures was noted by health service providers. A good example of recognising and fostering joint endeavour and organisational change is the ‘CQI is everybody’s business’ slogan that is synonymous with the successful Northern Territory CQI collaboratives. The motivation for community members is poignantly expressed in terms of health of family members.

Specific initiatives to enhance the effectiveness of existing CQI initiatives might involve: recruiting and supporting an appropriate and well-prepared workforce (through appropriate orientation and support materials); training in leadership and joint decision making; supporting and expanding the role of regional CQI collaboratives; and developing workable mechanisms for two-way community engagement. Some of these recommendations for policy and practice are outlined in more detail in box 1.

Box 1. Recommendations for policy and practice.

Support the health workforce to develop two-way relationships with community members so improvement processes are embedded in culture and genuine engagement.

Facilitate a prepared and stable workforce with attention to optimising the Indigenous and non-Indigenous workforce mix in staff recruitment, orientation and retention.

Ensure that health service operational and information technology systems support the routine practice of continuous quality improvement (CQI) by all health service staff.

Institutionalise a quality improvement approach through collaborative decision making and embedding CQI in orientation, staff training, regular team meetings and regional partnerships.

Make the purpose of quality improvement explicit and shared with a focus on improving client care and health outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

This research has focused on learning from in-depth study of a sample of six Indigenous PHC services across northern Australia. All services were selected based on sustaining high improvement in more than one audit tool over at least two cycles in CQI initiatives. We aimed to understand how these services operationalised quality improvement, ‘the secrets of their success’ at a local level. This focus on depth rather than breadth in numbers of services necessitates some caution in generalising from the findings, however, a number of factors enhance confidence that the findings are likely to have wider applicability across a broader range of Indigenous PHC services, particularly those in northern Australia and outside major cities. The participating services were broadly representative of a range of service types, included three jurisdictions, a range of community sizes, rural and remote communities and both government and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. Some were extremely isolated and discrete services, but two of them were major ‘crossroads’ communities, located at transport intersections, with a range of language groups and communities attending the service. Thus, findings are likely to be generalizable to some extent within the Australian Indigenous PHC context. The principles identified in working with vulnerable and marginalised communities to engage them in ownership efforts to improve their health and acknowledge their cultural beliefs are likely to be applicable to in many other parts of the world.

In addition, a strength was the large number of interviews (134), and the involvement of Aboriginal researchers in both data collection and interviews and in the analysis of the qualitative data. Involvement of key stakeholders from the participating service as part of the project team has enhanced the rigour and trustworthiness of our analysis and enhanced the two-way learning embedded in our partnership approach to research.

Conclusions

Services successful in improving quality of care: (1) make CQI ‘everyone’s business’ by involving a wide range of stakeholders, including community; and (2) make explicit that CQI supports a shared focus on improving client care and health outcomes. The services involved active, visible and actionable engagement and input with and from the community as part of this process. These findings suggest that in order for CQI to deliver the desired outcomes, it is important to focus on ‘what’ is done and by whom, and the underlying assumptions and processes about how it is done and the role of the community in shaping these processes. The next step is identifying and implementing modifiable levers at each level of the system to use in implementation studies with services that are striving to improve their quality of care in response to CQI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all staff, managers and service users from the participating services for their contribution and colleagues from CRE-IQI who have helped shape their thinking.

Footnotes

Contributors: SL, RB, VM, KCo and ST conceived of the idea. NT, KCa, JT and SL were all involved with data collection and analysis. SL, RW, KC, SC, RB, ST, VM were involved in planning the project. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported directly by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council: Project Grant (GNT1078927) and through the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Integrated Quality Improvement in Indigenous Health (GNT1078927).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This work received ethical approval from Menzies/Top End Human Research Ethics Committee, from Queensland Health, from the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Forum and Western Australian Country Health and James Cook University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Qualitative data is held by the research team at James Cook University. Audit data is held by the CRE-IQI and is available on request.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Mickan S, Burls A, Glasziou P. Patterns of ’leakage' in the utilisation of clinical guidelines: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J 2011;87:670–9. 10.1136/pgmj.2010.116012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, et al. Achieving change in primary care–causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci 2016;11:40 10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olivier de Sardan JP, Diarra A, Moha M. Travelling models and the challenge of pragmatic contexts and practical norms: the case of maternal health. Health Res Policy Syst 2017;15:71–84. 10.1186/s12961-017-0213-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Paina L, Peters DH. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plan 2012;27:365–73. 10.1093/heapol/czr054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision. Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: Key Indicators 2016. Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tricco AC, Ivers NM, Grimshaw JM, et al. Effectiveness of quality improvement strategies on the management of diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012;379:2252–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60480-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matthews V, Schierhout G, McBroom J, et al. Duration of participation in continuous quality improvement: a key factor explaining improved delivery of Type 2 diabetes services. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:578 10.1186/s12913-014-0578-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Si D, Bailie R, Dowden M, et al. Assessing quality of diabetes care and its variation in Aboriginal community health centres in Australia. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2010;26:464–73. 10.1002/dmrr.1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schierhout G, Hains J, Si D, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of a multifaceted, multilevel continuous quality improvement program in primary health care: developing a realist theory of change. Implement Sci 2013;8:119 10.1186/1748-5908-8-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q 2010;88:500–59. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00611.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peiris D, Brown A, Howard M, et al. Building better systems of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: findings from the Kanyini health systems assessment. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:369 10.1186/1472-6963-12-369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573–6. 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gardner K, Bailie R, Si D, et al. Reorienting primary health care for addressing chronic conditions in remote Australia and the South Pacific: review of evidence and lessons from an innovative quality improvement process. Aust J Rural Health 2011;19:111–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burgess CP, Bailie RS, Connors CM, et al. Early identification and preventive care for elevated cardiovascular disease risk within a remote Australian Aboriginal primary health care service. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:24 10.1186/1472-6963-11-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Willis CD, Riley BL, Best A, et al. Strengthening health systems through networks: the need for measurement and feedback. Health Policy Plan 2012;27(suppl 4):iv62–iv66. 10.1093/heapol/czs089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cunningham FC, Ranmuthugala G, Plumb J, et al. Health professional networks as a vector for improving healthcare quality and safety: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:239–49. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bailie R, Matthews V, Larkins S, et al. Impact of policy support on uptake of evidence-based continuous quality improvement activities and the quality of care for Indigenous Australians: a comparative case study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016626 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peters DH. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking? Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12 10.1186/1478-4505-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Larkins S, Woods CE, Matthews V, et al. Responses of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health-Care Services to Continuous Quality Improvement Initiatives. Front Public Health 2015;3:288 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Panaretto KS, Wenitong M, Button S, et al. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. Med J Aust 2014;200:649–52. 10.5694/mja13.00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Woods C, Carlisle K, Larkins S, et al. Exploring systems that support good clinical care in Indigenous primary health care services: A retrospective analysis of longitudinal Systems Assessment Tool data from high improving services. Front Public Health 2017;5 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guba E. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educ Technol Res Dev 1981;29:75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Timmermans S, Tavory I. Theory Construction in Qualitative Research: From Grounded Theory to Abductive Analysis. Sociol Theor 2012;30:167–86. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adam T. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health. Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:50 10.1186/1478-4505-12-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldberg J, Bryant M. Country ownership and capacity building: the next buzzwords in health systems strengthening or a truly new approach to development? BMC Public Health 2012;12:531 10.1186/1471-2458-12-531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chino M, Debruyn L. Building true capacity: Indigenous models for Indigenous communities. Am J Public Health 2006;96:596–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Makuwira J. Communitarianism : Anderson GL, Herr KG, Encyclopaedia of Activism and Social Justice. New York: Sage, 2007:372–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gilson L. Health policy and systems research: a methodology reader. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sherwood J. What is community development? Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal 1999;23:7. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bovaird T, Loeffler E. From engagement to co-production: the contribution of users and communities to outcomes and public value Voluntas. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 2012;23:1119–38. 10.1007/s11266-012-9309-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peters DH. The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking? Health Res Policy Syst 2014;12:51 10.1186/1478-4505-12-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.